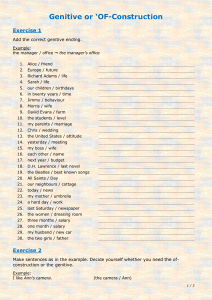

Class, Gender and the Family Business Kate Mulholland Class, Gender and the Family Business This page intentionally left blank Class, Gender and the Family Business Kate Mulholland © Kate Mulholland 2003 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2003 978-0-333-79336-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied to transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2003 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-41973-9 ISBN 978-0-230-50447-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230504479 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mulholland, Kate, 1949Class, gender, and the family business / Kate Mulholland. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Family-owned business enterprises. 2. Women-owned business enterprises. 3. Businesswomen. 4. Entrepreneurship. 5. Wealth. 6. Social conflict. I. Title. HD62.25.M85 338.7–dc21 2003 2003045183 10 12 9 11 8 10 7 09 6 08 5 07 4 06 3 05 2 04 1 03 Dedicated to Mike and Paul This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Tables ix Acknowledgements x 1 Introduction 1 2 The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 9 3 Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation: ‘His Dream and My Money’ 28 4 Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation: ‘He also Wants a Pudding’ 48 5 Gender and Wealth Preservation: ‘I’m Not a Member of My Husband’s Family’ 70 6 Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 89 7 The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life: ‘It’s Like Being a One-Parent Family’ 111 8 Women Owners: Honorary Men? 131 9 The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 151 10 Conclusions 180 Notes 191 References 194 Name Index 203 Subject Index 205 vii This page intentionally left blank List of Tables 2.1 2.2 2.3 3.1 3.2 9.1 9.2 Distribution of Wealth across Generations Distribution of Businesses among Couples Character of Diversified Enterprise among ‘New and ‘Old’ Businesses ‘New’ Wealth Couples: Distribution of Wives’ Contribution in Addition to Domestic Work ‘Old’ Enterprise Couples: Wives’ Contribution in Addition to Domestic Work Distribution of Ethnic Minority and White Majority ‘New’ and ‘Old’ Businesses Diversified Business among Ethnic Minority and White Majority Categories ix 10 11 13 30 31 157 159 Acknowledgements I carried out the research for this book while I was a Research Fellow in the Sociology Department, at the University of Leicester, when I was working with John Scott and David Reeder. The research was supported by an ESRC grant, ROOO 23 2711, for the study of wealth creation. The relationship between gender, power and class relations has long interested me, and the management of the family business proved to be an excellent opportunity to explore this question. I thank all those who participated in the research, and especially the business families who co-operated and generously participated in the research, but must remain anonymous. I am also indebted to Keith Vaz MP for his help at the initial stage of the research. Chapter 2 is based on ideas from a conference paper, ‘The Gendering of Research: Politics and Power in the Study of Elite Families’, which I presented at the Researching Contemporary Elites Conference, Bank of England Museum, London, in 1996. The ideas about gender and exclusion discussed in Chapters 3–5 have been developed from an article titled ‘Gender Power and Property Relations within Entrepreneurial Wealthy Families’, in Gender, Work & Organisation, 3, 2, 1996, and have drawn on an earlier paper, ‘The Marginalisation of Women and the Processes of Wealth Creation’, in A. Sinfield (ed.), Poverty, Inequality and Justice (New Waverley Publications, University of Edinburgh, 1993). The theme of enterprise, emotional labour and gender relations addressed in Chapters 6 and 7 draws on ideas in ‘Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man’, in D. Collinson and J. Hearn (eds), Men as Managers: Managers as Men (London, Sage Publications, 1996). An earlier version of Chapter 9 was published in an article in Work, Employment & Society, 11:4, 1997. This book has been written during 2001/2002 and I wish to thank the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford for generous access to the library facilities. My thanks go to Jane Roberts for her careful reading of drafts of several chapters and to Mike Mulholland for his incisive reading of Chapters 1 and 2. I am much indebted to Mike Mulholland and Paul Mulholland for their support and encouragement whilst writing this book. Finally, I would like to thank Jo Campling for her encouragement and support for the idea of the book and for her constructive criticism throughout. x 1 Introduction The focus of this book is the wealthy family enterprise and the manner in which it shapes gender and class relations. There has been very little systematic sociological inquiry into the wealthy, how they make and conserve their wealth, and in particular the part played by women. Yet according to the popularly held view, the wealth men own and control is a result of their sole efforts. The role played by women is ignored, and the wives of business leaders and family women generally are stereotyped as male trophies and consumers of such wealth. One of the main concerns of this book is to challenge this assumption and popular stereotype. The second concern is to explore where power lies in business family strategies and how it affects the division of labour and the career paths of family kin. This raises the question why women in wealthy entrepreneurial business families, who appear to have considerable power, are unable to exercise that power. In examining these questions, the book places its central focus on the processes of private wealth-formation amongst wealthy families and questions the assumption that there is a simple correlation between male effort and dominance in the ownership and management of wealth. Asking the question whether and in what ways family women play an entrepreneurial role in the business suggests that it is essential to place family women at the centre of the research gaze. This shows that family women play a key role in the creation of family wealth. It also demonstrates how male kin appropriate women’s efforts, how women’s progress within the business is thwarted, and how they are marginalised in the management of such enterprise and excluded from ownership of private wealth. Finally, it will explain how such patterns of exclusion, taking account of ethnic differences, are part of a wider coherent business strategy that 1 2 Class, Gender and the Family Business both reproduces and sustains the dominance of male management and ownership of the family business. Chapter 2 is organised into four sections. The first focuses on the research and describes the character of the family businesses studied. It includes tables that categorise the age, activity and business sector and indicate whether the businesses were inherited or newly established. It also defines enterprising activity according to Scott’s (1994) notion of income. The second section reviews a range of literature that includes business directories, entrepreneurial theories and biographical accounts of enterprise and academic studies. It argues that these sources are characteristically gendered and that, in failing to question women’s absence from enterprise, they present a predominantly masculine picture of business. This is problematic, because the silence about gender inequality and the neglect of power relations lend a coherence to this literature, which has a powerful influence sustaining the connections between men, enterprise and wealth. The third section argues that a gender analysis is essential to the study of family capitalism and that a non-gendered approach requires that family women, like men, are the focal point of the research gaze. In order to highlight the centrality of family women’s enterprising activity, the chapter sets out the major tenets of a research strategy that is capable of interrogating male accounts of enterprise, whilst overcoming women’s silence and invisibility. The final section of this chapter examines the theoretical perspectives adopted. The discussion on patriarchy provides the framework in which issues of power relations, labour, emotion work and women’s marginality are debated. The focus then shifts to male power and the manner in which male friendship and competitiveness not only shape the masculine image of enterprise, but are also critical to the accumulation process. Drawing on the reformulated and non-gendered notion of enterprise, subsequent chapters challenge gendered stereotypes of women and men in the family business. Chapters 3–5 illustrate that the creation of family enterprise involves three phases – wealth creation, wealth accumulation and wealth preservation – which in practice operate in a chronological and cyclical manner in the creation and reproduction of private capital. This process is drawn on to demonstrate the interplay between capital and gender power in the allocation of power and position amongst family kin in the business enterprise. Organising the research in this way provides a framework that reveals how the distinct phases have different career outcomes for male and female business partners. Introduction 3 Chapter 3 starts with the business creation phase and examines how businesses are founded. It shows that resources such as investment capital, skills, family heritage and, not least, family labour, and particularly wives’ labour, are key resources during start-up. It also comments on the location and character of the businesses studied. This chapter focuses on the manner in which gender identities influence the connections between resources, including labour, capital and business opportunities. However, the aim in this instance is to explore how this connection is influenced by the power allocated to the husband via marriage. It is this power that distinguishes male from female partners for it allows them access to and potential control over women’s labour in ways that are inconceivable in a reversed scenario, but which constitute resources imperative to business formation. This suggests that such mixed partnerships are double-edged for wife partners, for while they allow them greater access and experience in a wider range of businesses, they deny them equal partnerships and confine them to a subordinate role that advantages the business at start-up. The chapter draws on businesses in farming, the manufacture of hygiene equipment, the hotel business, property development, finance, clothing manufacture, textiles and concept furniture to show how such partnerships work in practice. In drawing on examples, it shows that wives finance business, establish business, bring core technical expertise to the enterprise, take on the operational management of such enterprise and, not least, offer emotional support to their husband/partners. Contrary to stereotypes of family women, the range of tasks they undertake suggests that they are key players in the organisation. Chapter 4 locates the question of the systematic marginalisation of wives and female kin from the organisation of the family enterprise within the second phase, that of wealth accumulation. Wealth accumulation is equated with the establishment of the business in organisation form manifested in bureaucracy, the formulation of managerial structures, hierarchies and the specialisation and professionalisation of function. The research suggests that this development marks a breaking point for the careers of family women and of wife/managers in particular. Drawing on businesses in clothing manufacture, the manufacture of hygiene products, the hotel business, finance, office furniture, niche clothing and food manufacture, the chapter traces the careers of husband and wife partnerships within the dynamics of the particular organisational politics, and suggests that while husbands follow a destined career path, wives struggle against a process of exclusion. What emerges is a pattern of systematic marginalisation that can be accounted 4 Class, Gender and the Family Business for, first, in the power men have as husbands, and second, in the logic of men’s interests in their capacities as husbands, men and entrepreneurs. However, the range of managerial competencies that such women bring to the partnership challenges human capital-based theories of exclusion, typical of Becker’s (1985) account. This includes the women’s technical skill upon which clothing manufacture depends, personnel management skills in culturally specific contexts and, generally, their financial expertise demonstrated in the concept furniture business. In addition, ideologies of domesticity and femininity associated with women benefit some enterprises, such as the hotel business, when some businesses are marketed around homely cosiness and the family. In highlighting the range of wives’ managerial roles, Chapter 4 argues that these wives make a huge investment in the development of both their managerial competence and their businesses. Although they generously give their labour and finance, they are unable to withstand the challenge from their husband/partners in the management of such enterprise. Framed within the phase of wealth preservation, Chapter 5 addresses the question of business ownership, the conservation of wealth and its relationship to the gendered character of family power and authority. In particular, it examines the processes that lead to the bypassing and exclusion of wife partners from the ownership of core wealth. This chapter argues that primogeniture1 and the influence it exerts in terms of capitalist survival and lineal preservation provide the principal explanation for the exclusion of wives and women generally from the ownership of business, which in turn suggests unquestioned and automatic ownership. Focusing on the manner in which enterprise is transferred strongly suggests that primogeniture transcends the link between wifely enterprise and direct ownership in favour of the eldest son and the male line. This pattern of wealth transfer is observed in a very wide range of enterprises, including garment manufacture, the manufacture of hygiene products, retail furnishing business, manufacturing, construction and property businesses, niche clothing, the restaurant trade, the hotel business, brewing, food manufacture, machine-tool manufacture, land ownership and property development. The chapter also provides tentative insights into how the legacy of coverture,2 the transcendence of class over gender interests and natal bonding lead to the severing of the relationship between wifely entreprise and ownership, but in turn contribute to the perpetuation of primogeniture. While the family enterprise has been conceptualised as a chronological process, these three chapters focus on the dynamics in which wives engage in the Introduction 5 establishment of enterprise, are ultimately undermined, are rendered peripheral in the management of such enterprise and, finally, are excluded from ownership. At the same time, by conceptualising the family enterprise as a cyclical process, this chapter puts into context how wife/partners continue to contribute to patterns of socio-economic activity in the reproduction and perpetuation of such enterprise. The chapter also draws attention to the issue of reward and recognition for the family women for, as these chapters show, many such women continue to work in the enterprise well after business set-up. Chapters 6 and 7 explore the question of male emotion, the work ethic and enterprise, and locate the debate within the theme of presence and absence. These chapters argue that emotion work is critical to enterprise, but so far, with the exception of Davidoff and Hall’s (1987) work, such questions have been largely neglected. Chapters 6 and 7 argue that emotion work is a central business resource and is articulated in distinct ways. For instance, Chapter 6 suggests that male emotion is disguised as creativity, passion, drive, dedication and commitment. However, it also argues that although the act of enterprise is played out in the arena of emotional display, other aspects of entrepreneurial discourse, such as rationality, a key feature of ‘hard’ masculinity, represents an ideology that conceals the appropriation and consumption of male emotion in the service of enterprise. The theme of emotion work is also explored in Chapter 7 with specific emphasis on the notion of absence. This suggests that the male work ethic is dependent on the role of male emotion as absence from domesticity, on the sexual division of labour and on the conventional organisation of domesticity. In this sense, the chapter argues that entrepreneurial ideologies tend to prescribe male emotion for the preserve of the enterprise. These arguments are explored within the context of Ochberg’s (1987) study, which insists that men limit their emotion work in the private arena. Finally, the purpose of these chapters is to show that emotion work, men’s absence from the household and women’s work are resources that contribute to the creation of wealth. By unravelling the notion of the ‘self-made man’, Chapter 6 reveals the connection between emotionality, domesticity, masculinities and enterprise. In developing this argument, Chapter 6 constructs two typologies of entrepreneurial masculinity, the company man and the takeover man, showing that, despite the appearance of difference, they share a relation that is similar to the domestic sphere. Contextualised in themes of absence and presence, the notions of male sacrifice and workaholism are debated to 6 Class, Gender and the Family Business suggest that male partners absent themselves emotionally from the domestic sphere in order to transform their emotional energy into creativity and business formation, and whilst simultaneously abdicating their patriarchal responsibilities to their partners, draw on wifely emotional labour. The themes of absence and presence are used to convey the manner in which such men engage in sets of relationships that are mutually reproducing, whilst constructing masculine configurations through engagement in public sphere activities and non-engagement with private sphere emotion work. There is a shift of emphasis in Chapter 7, which explores the dynamics of the sexual division of labour and the relationship between home and work. In particular, it draws attention to a neglected dimension – the issue of male emotional investment in the domestic sphere. It asserts that the impact of male entrepreneurs’ work activity is so pervasive that it invades and colonises the household, with the subsequent effect of introducing a particular order to domestic life. Such ordering of domestic activity appears as a contradiction, for, on the one hand, as the earlier chapters reveal, most enterprising men argue that they draw a very sharp distinction between work and home activity. In this sense, the control of the household seems to be the responsibility of their wives. On the other hand, as this chapter will reveal, such ordering is in itself prescriptive and appears to extend a permutation of capitalist logic to the household. Of course, such men’s absence from the household, and their preference for a disengagement from the messy arena of emotional work, obscures the extent to which they attempt to regulate, not least wives’ physical labour, but also the whole remit of emotional management in the service of the enterprise. The sharp separation between work and home seems to be validated by men’s absence, but this neat division conceals many ambiguities. Chapter 7 argues that the demands of the enterprise may reduce men to breadwinners, but it also rationalises the organisation of the household in a variety of ways, particularly the manner in which husbands and wives utilise their emotional labour. It suggests that such men reserve their emotion for activity within the enterprise and that the energies (physical and emotional) of the wives via their spouses are also consumed by the same activity. The focus of Chapter 8 is five independent female business owners, the proprietors of four businesses. Two of their businesses are newly created and two are inherited. They are in a range of economic sectors – plastics manufacturing, organic cosmetics, livery and estate ownership combined with corporate entertainment. In contrast to Goffee and Scase’s (1985) and Allen’s (1991) findings, it is argued that similarity, as Introduction 7 opposed to difference, with male-headed business characterises femaleowned enterprise. In examining their approach to business, it is argued that these five female entrepreneurs establish, manage and preserve the ownership and survival of their enterprise in ways that are similar to their male counterparts. The five women are unique, for they seem to have ignored or circumvented their gender constraints in the masculine business world. For instance, out of a total of 54 ‘new’ businesses, only two first-generation businesses, the livery and the cosmetics enterprise, have been established by women, and continue to be managed and owned by them. These two women are remarkable, for they have, of their own volition and against all odds, defied convention and entered the male world of business. The third female-owned enterprise, a ‘new’ business in plastics manufacturing, a recent acquisition, had been bequeathed by the male founder to two of his daughters, who have undergone training and socialisation typical of men. The fifth woman, in the absence of a suitable male heir, inherited a title, a large country house and land, and is the only female landowner. This chapter suggests that the notion of a shared business culture (Mulholland, 1997) is appropriate in examining women’s entry into business. Like their male counterparts they benefit from the material attributes of a middle-class background, which in a distant but important way helps them to cross conventional gendered class boundaries. They also acquired particular kinds of knowledge and skill specific to the business they subsequently entered. In this sense, their business entry is pre-empted by their cultural capital and training. It is also argued that female entrepreneurs are similar to men in a second major respect, and this concerns the management of business finance. They are risk-alert and, like their male counterparts, enter businesses that require little capital outlay at start-up and rely on family resources, particular kinds of personal expertise and access to cheap labour. Chapter 9 explores the ways in which the family business is largely driven by and dependent upon a shared business culture (Mulholland, 1997). Contrary to cultural accounts, it is argued that business stems from the similarity in the class background of the actors concerned, a shared value system and common business strategies that take account of ethnicity. It also explores the role that the family institution plays as a socialisation agent and purveyor of such business culture. Bourdieu’s (1976) notion of habitus3 puts into context how a shared culture operates in practice and as experience. Roberts and Holyroyd’s (1992) discussion of substantive rationality conveys the sense in which such family socialisation practices underpin a class strategy or best way of manag- 8 Class, Gender and the Family Business ing the succession and financial management of businesses. Chapter 9 also demonstrates how substantive rationality, characteristic of gendered kinship relations, interweaves with modern rationality. This is highlighted in male apprenticeship and the acquisition of financial competence, one of the key principles of a shared business culture, the logic of which is to ensure the survival of the enterprise and the regeneration of the family and their class position. In this sense, it also argues that the shared business culture (habitus) serves as a class strategy and is embedded in, and is an elaboration of, culture as the reproduction of patterns of rational socio-economic behaviour over time. In shifting the focus to family men, this chapter also identifies the connections between primogeniture, business leadership and class survival. Finally, Chapter 9 questions the cultural approach to enterprise characteristic of Werbner (1984) and the idea that there is necessarily an exclusive link between specific cultures and enterprise to the exclusion of others. Taking account of the ethnic identities of the entrepreneurs concerned, Chapter 9 makes two important points. First, it draws on data that explain that all the families concerned pursue particular practices that can be regarded as a shared business culture. Second, it argues that that such practices are rooted in class resources and are manifested in the practice of creating, managing and sustaining the family enterprise. It will be shown that particular families adopt a very particular approach to leadership, succession and the production of specific human capital and entrepreneurial expertise. In focusing on business growth and business investment, this chapter provides other insights into the financial management of family enterprise. Boissevain’s (1974) notion of social capital puts into context the manner in which all entrepreneurs draw on their cultural practices in the development and management of their enterprise and that such cultural practices are embedded in class relations and are thus aspects of a wider business strategy for all businesses concerned. 2 The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives The research for this book was conducted in one of the Midland counties of England and is based on an extensive study of 70 wealthy business families involving over 100 family members, categorised as ‘new’ and ‘old’ enterprises. In the ‘old’ wealth category are 26 secondgeneration or inherited businesses, which have survived several generations of family management. Forty-four of the businesses are newly established and constitute first-generation enterprise. ‘New’ business refers to instances where the founding member is still in control. In respect of ethnic composition, the study consists of 52 white majorityowned businesses and 18 ethnic minority businesses. The ethnic minority enterprises consist of East African Asians, Asians, Anglo-Jews and one Irish, and are ‘new’, first-generation businesses established in this country. The 70 businesses consist of approximately 30 women and 70 men. There are 58 married couples and, as Chapters 3–5 reveal, many are also business partners and will be referred as husband and wife partnerships. Of the twelve remaining businesses, there are seven single men and five female owners. It is noteworthy that only two of the women are firstgeneration entrepreneurs who had set up their businesses in partnership with their husbands; two of the other women inherited their second-generation business and the fifth inherited a small estate, a large house and associated enterprise. The dominance of husband and wife business partnerships alongside the dominance of male ownership raises important questions about how the dynamics of gender and class power affect the processes of wealth accumulation and the management and distribution of property. 9 10 Class, Gender and the Family Business Concept of wealth and wealthy businesses In order to explore this question it is important to start with an interrogation of the notion of wealth. According to Scott (1994), wealth must be understood in relative terms. He argues that it refers to the advantaged possession of personal assets. In this sense the wealthy are those who are materially advantaged. This departs from the conventional idea that wealth refers exclusively to those with unearned income. For the purposes of this study wealth refers to units of private business with earned and/or unearned assets. The criterion for inclusion in the study was that participants had assets of at least £1 million. The size of wealthholdings of those studied varied; most have assets far exceeding the £1 million cut-off.1 However, it is difficult to make a valuation of any of the businesses studied, not least because this is dependent on the character of the enterprise, the location and market conditions. Assets included businesses, investments, trusts and personal property such as private dwellings, as well as other valuables, including paintings, antiques, jewellery, cars, planes and yachts. Interestingly, the most recent edition of The Sunday Times’ Book of the Rich (2003) confirms that the largest wealthholders have not only sustained but have also increased their wealthholding. Table 2.1 shows the distribution of wealth across the generations and the general area of economic activity of the 70 businesses studied. Table Table 2.1 Distribution of wealth across generations Category of Business ‘New’ Wealth, First and Second Generation ‘Old’ Wealth, Third Generation and Later Total Land Civil Engineering, Quarries & Construction Manufacturinga Textiles Property Finance Food/Drink Service Sectorb Diversified 6 15 21 2 5 5 2 3 0 9 12 1 3 1 1 0 2 2 1 3 8 6 3 3 2 11 13 Total 44 26 70 a. Machine tools, plastics and motor cycles. b. A variety of businesses, including printing, hairdressing, travel and computer software. The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 11 2.2 shows the sectoral spread of the businesses and their distribution amongst the ‘new’ and ‘old’ business couples (58 couples and twelve [seven male and five female] single-headed families). Tables 2.1 and 2.2 show that the businesses are distributed across a wide range of economic sectors, including land, quarrying, construction, manufacturing (textiles and engineering), and the service sector (finance, property, computing and food). The tables show that the businesses are divided into two categories: ‘new’ and ‘old’. ‘New’ wealthy businesses are those set up between 1930 and 1990, but most of the newly wealthy went into business in the 1970s and earlier. Contrary to the claims made by the pundits of the enterprise culture, only a minority of the 70 businesses started in the 1980s, and certainly are not drawn from redundant workers or coalminers. As Table 2.1 shows, there are 44 ‘new’, or first-generation, businesses. These are still managed by their founders, and/or are in the process of being passed to the second generation. Table 2.2 shows that 39 of these are run by husband and wife business partnerships, with the greatest number of businesses concentrated in the diversified sector, followed by the service, textiles and landed sectors. In contrast, ‘old’ or inherited businesses refer to those businesses established some time in the past, and handed down to the present generation through the family. Table 2.1 indicates there are 26 in this category, and Table 2.2 shows that 19 of these are also managed by husband and wife partnerships. The tables show that land-based businesses are Table 2.2 Distribution of businesses among couples Category of Business ‘New’ Wealth, First and Second Generation ‘Old’ Wealth, Third Generation and Later Total Land Civil Engineering, Quarries & Construction Manufacturing Textiles Property Finance Food and Drink Service Sector Diversified 4 9 13 2 3 5 2 3 0 8 12 0 3 1 1 0 2 2 1 2 6 6 3 3 2 10 13 Total 39 19 58 12 Class, Gender and the Family Business numerically dominant in the ‘old’ wealth category and, surprisingly, constitute a significant number in the ‘new’ wealth category. The remaining businesses are distributed among subsets of the latter, while a few are in manufacturing. It is very significant that nearly half of the couples in the ‘old’ category have land-based businesses (Table 2.2, column 3) and this trend towards particular sectoral concentrations would seem to have important implications for the issue of gender and the ownership and management of the businesses. Fifty-seven of the businesses derive their wealth from one sector only, while thirteen are diversified. Table 2.3 shows that 13 of the ‘new’ wealthy families and one ‘old’ wealthy family have businesses in more than one sector. Two aspects of a wider accumulation strategy can be observed from this table: the first is the sectoral shift from one area of business to another; the second is the apparent concentration of business activity in particular sectors such as property and land.2 This trend suggests that the ‘newly’ wealthy emulate the accumulation strategies of the ‘old’ wealthy in the acquisition of land and real estate. These are particularly valuable forms of property. Depending on the location, commercial building has the potential of yielding considerable income from rents; the other advantage is that they are considered stable accumulative assets, which were at the time of the research regarded as safe investments. The shift to these sectors from more labour-intensive sectors such as textiles may also represent a reduction in labour costs. For the purposes of this study it is important to inquire whether and in what ways these shifts have implications for the positions of male and female kin within these enterprises. The gendering of the business and the gendering of the research This section argues that sources such as business directories, entrepreneurial theories and much of the biographical literature require a gender analysis, because the definition of ownership rooted solely in male enterprise is at most a partial and distorted account of how the family business is actually established. Characteristically, there is a silence about women’s absence. However, Pateman’s (1988) philosophical notion of the ‘unity’ of the marital relationship suggests the ways in which wives are rendered invisible in business partnerships, for they ‘disappear’ in the person of the husband in the public sphere. As this section demonstrates, the disappearance of wives as business partners is The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 13 Table 2.3 Character of diversified enterprise among ‘new’ and ‘old’ businesses ‘New’ Business Couples Couple Number Source of Wealth ‘New’ Diversified Wealth N28/N29 Trade in East Africa N30 Speculative building N31 N32 Printing Plant hire N33 Textile manufacturing N34 N35 N36 Manufacturing & distribution Finance Retail/Food N37 Property N38 Food manufacturing N40 Textile manufacturing Textiles export Pharmaceuticals & textiles Speculative building Vehicle manufacture Farming Hairdressing & property Civil enginering Estate Farming Open cast mining Property development Wholesale textiles Property development Manufacturing Property development Finance/hotels Travel/insurance & estate agencies Advertising Employment agency Asset stripping Playing the Stock Market Property Food manufacturing Estate farming Rare books Property development Art galleries Total = 12 ‘Old’ Business Couples Couple Number Source of Wealth ‘Old’ Business Couples O 19 Land estate Estate Stockbroking Total = 1 N = ‘New’ wealth, O = ‘Old’ wealth. Couples N28 and N29 are members of an extended family and share one business portfolio. This table shows that thirteen of the ‘new’ wealthy families had derived their wealth at the time of the interview from more than one sector, while this was the case for only one of the ‘old’ wealthy families. Column 2 indicates the character of business at start-up, while column 3 indicates the shifts between sectors and the spread of investment. 14 Class, Gender and the Family Business the articulation of the gender effect of this convention and underpins a very broad range of documentation of a highly influential character. Although business directories and other documentary sources such as Burke’s Peerage, local histories and newspaper business sections are indispensable in tracking patterns of ownership, they say nothing about the process of wealth accumulation. Another example is the Doomsday Book, which is based on the Land Valuation Act 1911, a survey listing the acreage assessed for the valuation of individual owners in each parish across the counties studied. Although this important source made it possible to examine patterns of land ownership among men from 1873 to 1911, and despite historical studies (Thompson, 1976) showing that dowries and marriage settlements typically contribute to such wealthholding, this is not mentioned. Kelly’s directories, another source identifying male ownership in other business sectors for the period 1936–46, a period when women increasingly entered paid work, reveal the same rigidities. However, these sources identified the principal landowner and size of acreage, and as such provided some of the background data complementing the fieldwork. The importance of Burke’s Peerage as a data source is that it confirmed the ancestral roots and the age of the wealthholding, as well as identifying businesses in the landowning sector. The economic role that female kin are likely to have played in the building of wealth is also ignored in historical editions of Who’s Who, which identified rich families in other areas of business such as brewing. Characteristically, by focusing exclusively on male wealthholders, these sources endorse the tradition of identifying wealth with the male line. Of course, these sources are useful, for they enable the descendants or the present owners of ‘old’ wealth to be traced through contemporary sources such as business directories, press reports, consultation with community leaders and personal recommendation. The ‘new’ business sources reveal the same absences. These include business directories, The Sunday Times’ Book of the Rich, the business section of national and local newspapers, and reputation. Some of the ethnic minority business leaders are also drawn from a separate business directory. An entrepreneurial reputation and a flair for publicity proved especially effective in the identification of entrepreneurial men. Entrepreneurs in speculative building, farming, quarrying and food manufacture were identified by The Sunday Times’ Book of the Rich and were major wealthholders. National and local newspapers identified others in textiles. The remainder were identified through consultations with community leaders, local notables, as well as personal recommendation, to reveal the dominance of male ownership. For instance, The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 15 these sources confirmed that men were major shareholders and senior executives within their enterprise. However, there were some exceptions and the research uncovered five businesses headed by women that were independent of men. Current entrepreneurial theory represents a shift away from structure, and the embrace of neoclassical economics means a sharper emphasis on theories of human capital and individualism, exemplary in notions of the ‘self-made’ man. The significance of this is that it ignores the question of the wider ‘resources’ that determine the fate of business activity, while lending credibility to the essentialism that characterises human capital theory. This is evident in the assumption that it is possible to correlate personality types with business activity. This means identifying individuals with the ‘right’ qualities, which include risk-taking, innovation, decision-making, leadership, courage, perception, opportunism and dynamism in the manipulation and management of market activities (Kets de Vries, 1977; Hebert and Link, 1989). This is problematic for women in business, for these attributes have a long association with masculinity, and, reflecting Elson and Pearson’s (1981) and Cockburn’s (1983) convincing arguments concerned with skill constructions, suggest that they are embedded in particular class/gender identities. The currency of the self-made image of business leaders is illuminated in the biographical literature (Lynn, 1974; Kennedy, 1980). This suggests that the wealth and success enjoyed by particular businessmen can be accounted for in their unique talents and personal ambition, relying on modern variants of Samuel Smiles’ self-help, which, during the 1980s, became the hallmark of Sir Keith Joseph, and later Norman Tebbit’s recipe for enterprise. Individual male effort is extolled around the discourses of the ‘self-made’ man and stories of ‘rags to riches’ business success. No mention is made of the links between individual activity and resources, such as the availability of capital for investment, skills, economic climate and other forms of help, such as family labour – women’s labour in particular. It is not surprising then that sections of popular literature and the quality press present female kin in entrepreneurial families in a traditional and stereotypical manner. For instance, an article in Business Week (October 1992) typifies the way in which wives in particular are presented. They are cast as conspicuous ‘trophies’, the adornments of very successful men, or are more subtly portrayed as dutiful companions playing the traditional supportive role, not overshadowing the central figurehead, the entrepreneurial man. The manner in which each of 16 Class, Gender and the Family Business these strands of popular discourse assumes that such men carve out fortunes for the benefit and consumption of female kin serves to reproduce the gendered, stereotyped interconnection between business and the family head. Entrepreneurial discourse is problematic for women in other ways. It takes no account of how power structures relate to class and gender, and parodies neutrality whilst addressing a male audience. However, other research, such as that by Chell et al. (1991), whilst claiming to take account of agency and structure, fails to see the significance of gender relations, and is illustrative of the manner in which different discourses lend potency to contemporary, ‘self-made’ entrepreneurial ideologies. Whilst this conceals women’s financial investments, what also tends to be hidden are the ways in which men’s absence from domesticity contributes to the build-up of both the business and the particular masculine image (Mulholland, 1996a). In some ways there is little that is new about these representations because they mirror nineteenth-century entrepreneurial paternalism (Davidoff and Hall, 1987). At the same time, this literature conspires with market logic, exemplified in human capital theory, where women’s absence from most mainstream business activities can be explained by the inadequacy of their labour power and poor comparisons with men in aptitude and skills. But even if skill and aptitude were all that was required, they do not operate in a disconnected way, but rather are contingent on structure. The problem with this literature is that it ignores ‘structure’ and fails to take account of the relationship between material resources and personal skill, and is a repercussion of the disappearance of a class-focused approach. Major ethnographic studies, such as Scase and Goffee’s (1982) account of the business classes where wives’ contributions are considered, and Ram’s (1994) semi-autobiographical study of the clothing industry, are a significant advance, but they uncritically perpetuate the idea of women as helpers. While they seem to account for gender in that they acknowledge that female kin are involved in the enterprise, they are sanguine about the hierarchy and the inequality they observe. Very often female kin undertake positions of responsibility, such as managers, which are also often unpaid. Describing them as ‘de facto’ managers and the positions they hold as ‘informal’ may be an apt and valid image, but it makes little attempt to evaluate such women’s work as enterprising activity within the boundaries of power relations. Ram calls this form of organisation a characteristic of authentic Asian ethnicity The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 17 and culture. In such instances the scope and value of female kin contributions are taken for granted. The impact of the apparent genderneutral (Kets de Vries) and gender-blind (Ram) approaches adopted by this literature allows the link between enterprise and men to continue. The failure to question and theorise the relationship between women and men and capital merely perpetuates conventional gendered stereotypes. At the same time, Ram’s work suggests that some of the ways in which discourses are packaged as culture are a fig leaf for gender inequality. It has been argued that the combined effect of different strands of literature has been to lose sight of the role of family women and enterprise. A non-gendered approach to research A non-gendered approach to the study of family enterprise requires that family women, like men, are the focal point of research. By focusing on the dynamics of the husband and wife business partnership, this book will show that the idea of the wife as the ‘helpmeet’,3 first introduced in Davidoff and Hall’s (1987) path-breaking study exploring the gendered character of nineteenth-century British industrial enterprise, continues to have potency. In adopting a non-gendered approach, this book will compare and evaluate wives’ contributions in establishing and managing enterprise, with the notion of the wife as helper. In taking on board earlier criticisms, a non-gendered notion of enterprise refers to both economic and ‘non-economic’ activities, dispersed among family members, consisting of female and male kin, who express a shared intention to expand their business during their lifetimes and to pass this wealth on intact to their heirs. This is inclusive of women and as such departs from the spirit of much of the theoretical and entrepreneurial discourse and empirical studies which eclipse and conceal women’s contribution to the creation of wealth. The highlighting of family women business partners entails going beyond formal structures and the largely male accounts of the rise of enterprise and wealth. Glaser and Strauss’s (1967) grounded theory, the life history approach and Harding’s (1987) standpoint theory provide the organising tenets for a research strategy that is capable of overcoming problems of women’s silence and invisibility. For instance, comparisons of male partners’ accounts of wifely help with women’s deconstruction of the male claim of sacrifice and effort expose the manner in which positions of power are competed for, contested and eventually negotiated in the family business. They also show that the 18 Class, Gender and the Family Business contradictions between domesticity and enterprise become points of tension in such husband and wife partnerships. The life history approach shows that, for some men, marriage is the precursor to business entry. This ties in to the idea that business improves the male role of economic provider. In such cases, entrepreneurial men make great play of their new roles as wealth creators and economic providers, and embellish notions of masculinity. However, the research also shows that marriage can be an opportunity to enhance enterprise through the resources wives bring to the business. In effect, the life history approach reveals how the private and the social interweave with economic activity in both male and female accounts of business formation. Since documentary sources name men as wealthholder they were the first points of contact. The study of the family business is an example of how coalitions of interests initiate alliances between capital and masculinity in a bid to protect common interests that pertain to the business and the family. For instance, as business heads, these men act as gatekeepers to both the business and to female kin. For example, access had to be negotiated through the business heads, who were initially contacted by a letter that briefly explained the purpose of the research. This was followed by a telephone call during which the terms and the location of the interview were agreed. Echoing Roper (1994), what is striking about the interviews with the male entrepreneurs is the consistency with which men invariably take the credit for their success, and in ways that justify their dominance in the management and ownership of such enterprise. In some cases the ambience and formality of plush business headquarters complement their images as powerful and self-made business leaders. This use of surroundings as a power accessory has a gender dimension, but is not one that is restricted to men, for two of the women entrepreneurs were prone to such power-play. The displays of power as confirmation of leadership stand juxtaposed to the manner in which such entrepreneurial men portray their wives’ roles. For although these family women are their business partners and have formal job titles, the men rarely portray them as such and continually refer to them in personal terms as their wives, whose place in the business is marginal. Typically, speaking of his wife’s business role, one entrepreneur commented: ‘She will be able to tell you about her invisible contribution.’ In so far as women are invisible in much of the business documentation, are portrayed in the media as male ‘trophies’ and accessories, The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 19 and are perceived to be informally occupied in the family business by academic reporters, this made the separate interviewing of family women critical. The interview offered a deeper insight into how family businesses are managed and allowed the women to tell their stories unhindered. However, access to the partner/wives had in most cases to be negotiated through the men. The research focus on the wives highlights the peculiarity of the family business in that it enables men to sustain patriarchal power by interchanging and conflating the role of formal business head and the role of family head. For instance, in their role of family head they drew widely on different aspects of domestic ideology. In some instances the role of protector is mirrored in the tendency to regard requests to interview wife/partners as an intrusion into the family sphere despite the women’s involvement in the business. In these cases, the fusion between home and business, and particularly the notion of the male protector, legitimises the male as the representative voice of the family and serves to overshadow and silence women/ partners. The formal power of the business head to control access was especially evident in cases such as the landed sector where the business is managed from the family home. However, such business heads gave guided tours of their private houses providing extensive comments on the artefacts of their affluence such as collections of paintings. This provided an interesting gaze into the meaning, symbolism and expression of business success, while saying something about lifestyles, consumption patterns and class aspirations. However symbolic of ‘success’, such displays of affluence endorse notions of effort and sacrifice. The manner in which such men manipulated the public/private split serves as a sharp reminder that men in contemporary economies can still draw effective support from domestic ideologies. The importance of the interviews with the entrepreneurial wives is that the women frequently challenged their husbands’ embellished accounts and the marginality of their own work in the enterprise. Many of the wives held jobs in the business, while others had worked in the business in the past. The informality of the conditions in which this work is performed spills over into the research and is articulated in the manner in which wives present their work in the business. The interviews with the women and the men also show how the material symbols of wealth become signals for class aspirations and class mobility. Like the business heads, the women in both ‘new’ and ‘old’ businesses view property such as houses as symbols of success and afflu- 20 Class, Gender and the Family Business ence. Since some of the interviews with the women were undertaken at home, questions about how such houses were acquired, their history and the meaning they had for the entrepreneurial family, seemed a natural and unobtrusive inquiry. Some of the ‘newly’ aspiring wealthy women were very concerned with class divisions and talked about the rigidity and subtlety of class boundaries, suggesting that material affluence was not a sufficient criterion for acceptance into certain social and cultural milieux. Power is also important to such women. Indicative of this is their resentment at social divisions that bar them from some social circles, while they are sanguine about other social divisions that enable them to hire domestic help. The informality of the family home was quite important, for the setting seemed to encourage the wives to discuss more openly their ‘invisible’ role in the business. This provided insights into the manner in which emotion work and wives’ labour are contested resources between entrepreneurial wives and their husbands. In order to explain the way gender divisions shape the enterprise of men and women within wealthy families, the book separates analytically the process of wealthholding into three constituent phases: wealth creation, wealth accumulation and wealth conservation. Wealth creation refers to business entry and start-up. Wealth accumulation is equated with the growth of the business, when the unit of capital takes on a particular identity. Formal managerial structures are put into place, accompanied by the specialisation and the professionalisation of function. At this point also hierarchy and power are symbolised in the management teams and boards of directors. Wealth conservation refers to strategies that safeguard and preserve wealth from fragmentation. The act of conservation, whilst involving wealth creating or re-creating tactics, also refers to inheritance patterns such as primogeniture, the heritage of coverture, gendered socialisation practices, male leadership ‘apprenticeships’ and the use of trusts, and is part of the strategic management of private wealth. While these must not be treated as sharply separated chronological stages, they do indicate distinct aspects and phases of wealthholding. In this sense they provide an indication of the way a new unit of capital develops, while they can also be understood as a cyclical process in the reproduction of units of newly created and inherited wealth. In order to demonstrate the manner in which power relations operate within the family enterprise the roles of men and women will be traced through the phases. Before doing this, it is important to locate the discussion within a theoretical framework. The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 21 Theoretical and methodological perspectives The broader debates that examine the relationship between social class relations and gender relations, such as Hartmann (1979) and Walby (1986), and Brod (1987) and Collinson and Hearn’s (1994) emphasis on masculinity, provide critical insights into the study of the family enterprise. Hartmann (1979) and Walby (1986) make a number of points that are central to understanding the dynamics of the husband and wife business partnerships. They assert that although men and capital are engaged in a contradictory power relationship, they have an interest in controlling women’s sexuality and labour, whilst their exclusionary theories suggest that men’s relationship to capital is highly contingent. However, in the case of family business strategies, issues of women’s labour and sexuality become critical resources at points in the evolution and perpetuation of the enterprise. Arguably, these questions are the centre-piece of the power-play that characterises the husband and wife partnerships through the different phases of the development of family capitalism. The importance of women’s sexuality and labour cannot be overstated, for they constitute resources that are essential to capital’s project and to sustaining what is essentially a changing pattern of male dominance. The limitation of the dual theorists’ notion of exclusion is that it cannot necessarily explain why distinct strategies such as primogeniture and the legacy of coverture, ‘cultural practices’ that are conventionally associated with the private sphere, the family and reproduction, effectively deny ownership to women. Other theorists (including Engels, 1972; Bourdieu, 1976; and Pateman, 1988) contribute to the debate on female sexuality and the wider issue of property relations and offer important insights into understanding the management of family capitalism. Engels’ (1972) materialist analysis of sexuality is sensitive to the character of gender relations within marriage. His discussion of ‘father right’ makes clear the logic of the materially rooted character of primogeniture, arguing that the reason men need to know their biological children is in order to transfer accumulated wealth across the male line; hence their need to control female sexuality. Pateman’s (1988) theory of female sexuality hinges more on why men as men have interests in controlling female sexuality and indeed introduces a subtle shift in the debate. One interpretation of her analysis of the sexual contract is that it is an argument about the institutionalisation of the regulation of female sexuality. It is thus a negotiation sensitive to male needs that very cleverly draws together the public (civil 22 Class, Gender and the Family Business society) and private spheres (domesticity) while appearing to make a distinction. This sleight of hand is replicated at the heart of the civil contact, which simultaneously says that women are and are not equal partners. This is demonstrated when the wife as an individual disappears in the notion of the unity of the couple personified in the husband. The husband represents the wife, who stands in the shadow of the figurehead. This is the philosophy that underpins coverture and Holcombe’s (1983) account of the extent it has been reformed properly raises some important questions. These relate to the status of wives and whether they can be regarded as autonomous individuals. If the person of the wife is no longer the spouse’s property, it begs the question why women business partners, in contrast to their male partners, have so little control over their careers within the business. However, it is spurious to argue that female sexuality and labour can be separated from the person, yet for wives in business partnerships with their husbands, it seems that the institution of marriage, in comparison with the conditions of an employment relationship, gives husbands far more control over how and where wives use their labour. In the context of the middle-class family business, coverture and primogeniture have a key influence in the regulation of female sexuality, biological and social reproduction within the institution of marriage lending support to the maintenance of enterprise and family social status. The fact that a significant number of the family enterprises are inherited raises the matter of how such cultural practices are perpetuated and reproduced. This poses an important methodological question, for the family enterprise compresses time by bringing together the past and present in the context of the newly created and inherited businesses. Bourdieu’s (1976) concept of habitus is a useful way of thinking about the ways practices sustaining such organisational forms are reproduced. Habitus conveys the sense in which social and cultural reproduction takes place over time, the underlying logic of which is to ensure material and class reproduction. Accordingly, habitus, or the best way of doing things, is neither structurally imposed nor voluntarily initiated. Individuals engage and co-operate in a set of practices and thought processes internalised through education and upbringing that culminate in a set of life strategies which perpetuate a particular kind of capitalist enterprise, the family business. The importance of Bourdieu is that he offers an insight into how class is experienced and reproduced at the level of everyday life. However, there are problems with his work. First, whilst habitus, or culture, is a useful methodological device in The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 23 helping to explain the resilience of such archaic practices as primogeniture, arguably it obscures the vitality of structure in the form of material resources in the perpetuation of this institutional form. Equally, it conceals the notion of interests, and particularly the interests the key players, capital and men, have in perpetuating such formation. Bourdieu’s (1976) main concern is to show how class configured as culture and convention places limits on the personal freedom of male heirs. At the same time, he takes for granted the assumed passivity of women as mere pawns in the patriarchal marriage and inheritance strategies, ignoring how men have a priori an interest in continuing this practice. Since the centre-piece of this book is the relationships between husbands and wives in business partnerships, a feminist approach is incisive in exposing that this relationship is based in hierarchy and power and is problematic for the women concerned. Ontologically, the effect of making women the focus of debate, as this discussion has done, is to portray them as victims, while there is also an assumption that the alliance between men and capital, however problematic, makes masculinity invincible. The discussion now turns to gender studies which emerged especially in the 1980s under the rubric of men’s studies and masculinity. This shifts attention away from the centrality of the relationship between men and women to a concern with the relationship between men. Collinson and Hearn (1994) succinctly articulated the problem when they pointed out that although men are the focus of attention, they are rarely the objects of scrutiny. By advocating the interrogation of patriarchy, such work challenges ahistorical and monolithic representations of male power and exposes divisions between men. Hearn (1987) uses a materialist analysis to map out the changing contours of male power that runs parallel with transformations in the character of production, whilst linking these developments with men’s appropriation of women’s labour. In portraying the resilient nature of male power, the thrust of the argument suggests that it is adaptable and changes in form. He argues that modern patriarchy is impersonal and complex, but operates by harnessing a structured web of relations amongst men which manages the exploitation of women, and thus represents a dramatic shift away from the personal power of the father. The question is, do studies such as this illuminate the power-play that entrepreneurial men engage in? Arguably, several aspects of this general theory have resonance for the study of enterprise. Although, the institutionalised configuration of father power has certainly diminished, it has not disappeared in the 24 Class, Gender and the Family Business context of family enterprise. There are significant parallels between historical configurations of father power and contemporary male wealthholders. In each case the entrepreneurs concerned have considerable power, which of course hinges in the contemporary world, just as it did historically, on a web of social relationships that at historical moments drew and continue to draw support from kin relations, through patronage and emotionally recognised bonds of love. The next section addresses three questions that are critical to entrepreneurial men and include friendships, competition and emotion. The conclusion that can be drawn from Brod’s (1987) studies on masculinity is that expediency underpins bonds of love and friendship between men. The kinds of major public projects that men have historically been engaged in have been acquisitive, expansionist and invariably dangerous, and have usually been on behalf of a figurehead. The poem Beowulf (Heaney, 1999) brilliantly depicts the manner in which success depends on the strength of male alliances, trust and fraternalism. However, tainted with competitiveness, history tells us that violence and betrayal often characterised this web of social relationships. In this sense, the persuasive forces that encouraged male bonding such as heroism and honour were also a social process that was divisive, and arguably has its parallels in the contemporary entrepreneurial process. Hammond and Jablow (1987) challenge the pure altruism that is claimed to characterise male friendship. They argue that famous heroic male friendships, starting with the earliest recorded versions – the Gilgamesh epic, David and Jonathan in the Bible, Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad, to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – exist at the level of myth only. Although classical Greek and Roman literature glorified notions of male friendship, Artistotle wisely noted that even perfect friendship retains some element of the useful and that the moral imperative of sentiment colours even highly expedient friendship. In this sense, sentiment merely masks what it essentially instrumental, implying that male friendships can be a fig-leaf for an ulterior motive that can involve incredible gain. Nevertheless, what seems clear is that, prior to the Industrial Revolution in some European cultures, male emotion, for whatever reason, played a recognisable and significant public role in the organisation of society and rather enhanced notions of masculinity. Whilst recognising that two major historical events, the Enlightenment (Seidler, 1989) and the Industrial Revolution (Kimmel, 1987), were The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 25 experienced at different moments across Europe, they brought changes to notions of masculinity in ways that still have resonance for contemporary notions of what it means to be a man. The issue of male emotion is a central theme in Seidler’s exploration of masculinity. In contrast to earlier European culture, where male emotion seems to have been an important aspect of male public life, he notes how the transcendence of abstract reasoning over intuition and emotion, the distinguishing characteristic of Western intellectual culture, negatively changed the role that emotion played in the construction of masculinities. Seidler’s experiential approach allows him to locate emotion as a feature of the way men live their lives, showing that they control their emotions and deny particular expressions of sexuality. The process of concealing male emotion and the exaltation of male sexuality as conquest are tendencies that set up new constructions of masculinity as ‘strong’ and ‘soft’ and as such create deep fissures between contemporary men. Chapter 6 shows how the theme of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ masculinity divides enterprising men from one another, and has particular resonance for the power-play that characterises competitive relations between entrepreneurial men. Kimmel (1987) argues that the advent of capitalism and economic transformation has highlighted differences between men. Approaching the question from a cultural perspective, Sherrod (1987) argues it was the competition generated by industrial capitalism that led to the breakdown of male friendships. The exigencies of the new economic system brought about a series of changes that had implications not only for male friendship, but also for gender relations. The emergence of capitalism, the market and waged labour fostered competitiveness amongst men of different classes and between men in each class. Waged labour, the distinguishing feature of capitalism, geographically separated home and work and forced working-class men to compete with each other for work. Equally, the material concomitant, the laissez-faire logic of liberal economic theory, glorified aggressive competitiveness amongst entrepreneurial men, undermining the whole notion of male friendships. According to Sherrod (1987), the issues of emotion, sexual identity and male friendship became key considerations in defining masculinity, causing deep divisions between men. Sexual orientation took on a new significance and differentiated ‘soft’ or effeminate men and ‘strong’ heterosexual men. The breakdown of male intimacy also changed the relationship between men and women, particularly within marriage, when men 26 Class, Gender and the Family Business began to look for affection and friendship in marriage. Alienated from each other, men sought intimacy and emotional support from women and marriage. However, Sherrod (1987) argues that the balance of gender power within marriage is not equalised, and this may suggest why men seem reluctant to reciprocate affection. This raises the question of how and where men channel their emotions. Arguably, the notion of romantic love encouraged love between men and women, but Davidoff and Hall’s (1987) analysis of nineteenth-century British capitalism suggest that the capitalist ethic and its ideological concomitant, puritanical Christianity, discouraged this within marriage. One interpretation of this study is that there was an attempt to rationalise marital sexuality and emotionality. Unfettered from the entanglements of domesticity, such entrepreneurial men would be free to pursue enterprise. Alongside this, the elevation of the values of the Enlightenment, principally, reason and objectivity, as Weber’s account of bureaucracy shows, were diffused in the administration of enterprise and increasingly shaped models of masculinity (Brod, 1987). This argument tentatively conveys the sense in which male emotion disappeared from the public sphere whilst still remaining submerged there. This is an important point, for Chapter 6 shows that male emotion, articulated as devotion, passion and drive, is critical to enterprise. Sherrod (1987) provides the most subtle account of how men conduct friendship in ways that are compatible with the primacy of their economic role, whether they occupy positions as workers, managers or entrepreneurs. Although his depiction of the distinctions between intermale and inter-female relationship is overstated, he argues that male friendships are essentially defined by competitiveness, and this is the case for entrepreneurial men. In essence, the gist of his argument is that male friendships are nurtured around ‘having fun’, or camaraderie. There is an expectation of companionship and commitment, balanced by unquestioned acceptance of non-intrusiveness, which avoids emotional display and does not challenge ‘strong’ masculinity. The sites for the construction for such friendships are often exclusive male clubs, which as the example of the business men’s dinner club (mentioned in a future chapter) suggests, while not intentionally serving individual enterprise, often can open up further opportunities. Friendships of this sort have resonance for Boissevain’s (1974) notion of ‘social capital’, the ideas embodied in Burt’s (1992) concept of ‘structural holes’ and, not least, Werbner’s (1984) discussion of the place of social events such as weddings in the context of particular ethnicities. The similarity is that these rather wider social networks which are cultural in character essen- The Study, Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives 27 tially facilitate co-operation and the formation of allegiances, which in the case of enterprise can yield future enterprise. Friendship and competition underpin the entrepreneurial relationship, as men struggle against women and other men for success and dominance. 3 Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation: ‘His Dream and My Money’ This chapter focuses on enterprise in different economic sectors and draws on examples of female enterprise to argue that women’s efforts and particularly wives’ contributions are crucial in the initial phase of wealth creation, during start-up. It examines how businesses are started, seeking to show that resources such as investment capital, skills, family heritage and, not least, family labour and particularly wives’ labour are key resources during start-up. In reporting considerable diversity amongst the husband and wife partnerships across very different sectors of the economy, the findings are in contrast to Allen and Truman’s (1991) pioneering work on independent women entrepreneurs, which suggests that women entrepreneurs are restricted to particular economic sectors. This finding draws attention to the question of gender identity and the gendered character of resources at the phase of business startup, for the research upon which this book is based suggests that men have more resources to access market opportunities, and that the market is more open to men. This chapter also illustrates that, aside from the structural disadvantages that women face in the phase of business start-up, the wifely role distinguishes them from their male counterparts. This difference and its impact for the division of labour in the management of the enterprise are illustrated by focusing on the interplay between partners during start-up, which convincingly shows that husbands have access to wives’ labour in ways that are inconceivable in a reversed scenario. In this sense then, such mixed partnerships are double-edged for wife/partners, for while it allows them wider access and experience in a bigger range of businesses, it confines them to a subordinate role which seems necessary to the enterprise at start-up. Tables 3.1 and 3.2 are intended to convey the range and character of wifely entrepreneurial contribution. 28 Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 29 Tables 3.1 and 3.2 refer to the activities of wives in business partnerships across wealth generations. Wives bring to the business partnership a range of resources, which include finance, labour and ‘non-economic’ or emotional support. Eleven wives (27.5 per cent) in ‘new’ businesses and four wives (21 per cent) in ‘old’ businesses invested in the family business and this often led to other kin members investing in the business. For the ‘new’ businesses twelve women (30 per cent), and for the ‘old’ businesses, one woman, made indirect contributions which were beneficial to the business. For example, in one case of ‘new’ wealth a wife was able to obtain machinery from her family. ‘Indirect investments’ include situations when the wife uses her salary to meet family commitments, freeing the husband’s earnings for the business. It was not unusual for such women to work in the business too, and despite the diversity of enterprise characteristic of the ‘new’ enterprises 20 wives (50 per cent) worked. Fewer worked in the ‘old’ businesses with seven wives (36.8 per cent) directly working in the business, most of which were in the landed sector. In one case, the husband, a stockbroker, had responsibility for the long-term strategic management of the estate, whilst his wife was involved in the day-to-day management (Table 3.2, couple O19). The reason women continued to work is directly related to the character and organisation of landed businesses where the domestic and market activities share the same location, and where the complexities of organising these duties can be more easily reconciled. However, women in this sector are less likely to have a formal job title and are therefore more likely to remain hidden. The only other formally recognised working wife is in charge of marketing and sales in a small food business (Table 3.2, couple O17). Symptomatic of this is that, despite women’s participation, none of the wives in the ‘old’ business sectors held a directorship. Yet the research with the women showed that in both ‘new’ and ‘old’ businesses, some of the women have sacrificed independent careers and incomes and take on the double burden of unpaid work in the business and housework. In contrast to the literature on enterprise, I want to emphasise the importance that structural circumstances have for individual men entering business. First, all the 44 ‘newly’ rich who entered business did so with the backing of resources of some kind. In terms of skill, the majority of the ‘newly’ wealthy came from a family with a business background, or had gained long experience by working in their particular business area before setting up independently. Some had the benefit of a background in business together with personal capital and some knowledge of the business world. The ‘self-made man’ was the Table 3.1 ‘New’ wealth couples: Distribution of wives’ contribution in addition to domestic work Category of Business Couple Land N01 N02 N03 N04 N05 N06 Civil Engineering Quarry Construction Manufacturing Textiles Property Finance Food/Drink Service Sector Diversified Total N07 N08 N09 N10 N11 N12 N13 N14 N15 N16 N17 N18 N19 N20 N21 N22 N23 N24 N25 N26 N27 N28 N29 N30 N31 N32 N33 N34 N35 N36 N37 N38 N39 N40 Wife’s Direct Investment in Business Wife’s Indirect Investment in Business Wife Works Directly in Business Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 11 (27.5%) 12 (30%) 20 (50%) N = New. Couples N28 and N29 are members of an extended family and count as one unit of wealth in Table 2.3. Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 31 Table 3.2 ‘Old’ enterprise business couples: Wives’ contribution in addition to domestic work Category of Business Couple Land O01 O02 O03 O04 O05 O06 O07 O08 O09 O10 O11 O12 O13 O14 O15 O16 O17 O18 O19 Manufacturing Textiles Service Sector Property Food/Drink Diversified Totals Wife’s Direct Investment in Business Wife’s Indirect Investment in Business Wife Works Directly in Business Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 4 (21%) 1 (5.3%) 7 (36.8%) O = Old. exception, and even then the experience of work was the prelude and often the training ground. However, with few exceptions, wives’ contribution played a key role during the phase of business start-up. In focusing on a range of businesses – farming, the manufacture of hygiene equipment, the hotel business, property development, finance, clothing manufacture, textiles and concept furniture – the chapter explores the character of such partnerships with an emphasis on the wifely contribution. One of the most important ways female kin contributed to the setting up of the family enterprise was by working directly in the business. What is interesting about the next two examples, both first-generation businesses, one in the landed sector, the other in the manufacturing sector, is that the start-up coincided with the couples’ marriages. What is at issue is the manner in which gender politics subsequently have a major influence in the contest over the 32 Class, Gender and the Family Business symbols of business success such as prestige and recognition. In both cases, it seems that the enterprises started off as a joint effort. In the case of the landed business it is the female partner rather than the husband who emphasises the theme of sacrifice and hard work, thus claiming the ‘self-made’ entrepreneurial profile. This business couple now farm 1,000 acres, producing a wide variety of cash crops, mainly cereals. The significance of the wider notion of resources cannot be overstated in this example, not least the benefits afforded to the starting entrepreneurs through the social advantages characteristic of a middle-class background. The husband is from a farming background, attended a prestigious public school and pursued a career in the Army. The wife was born in India into a well-known medical family with strong historical connections with one of London’s teaching hospitals. They had some ready capital for investment, but after they married the husband inherited 600 acres of arable land and they have farmed this as a profitable enterprise for the last 30 years. The wife played a key role in the partnership, contributing to the establishment of the business. Yet, the effect of gender power brings to the surface the tensions in the partnership over the division of labour. Keen to emphasise her role in the business, she insists: ‘I mean, when we got married, we just had a bed, and that is all we had in the house. We had to paint it, decorate it and take the washing to the launderette. I have been a farm worker, a farm labourer, tractor driver and gardener. You name it, I can do it. I gave up my nursing career when I got married and ended up doing this.’ (Table 3.1, N01) The husband was quite uncomfortable with his wife’s explicit description of the hard physical labour that was a key part of her work and reminded her of her more feminine skills: ‘And of course you are a wonderful cook.’ And turning to the researcher, he insisted, ‘By Jove, she is’ (Table 3.1, N01). Substituting as a farm worker, the wife’s labour was very important during the initial phase as it saved costs. They argued that a prudent approach to financial management and taking advantage of the economic strength of the farming sector in the 1970s enabled them to expand their business. They rented an additional 400 acres and were able to increase their output. The husband went into partnership with a colleague, taking on a third farm in a different county. During a twenty-year period they employed eight full-time staff and invested in Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 33 a variety of cash crops. The current business consists of crop production in potatoes for a large food manufacturer. They also produce sugar beet, wheat, barley, beans and rape seed on a fairly extensive scale. In addition, they rear turkeys for a large food manufacturer and other livestock. They are also involved in a seasonal business, a ‘Pick Your Own Enterprise’, which involves the production of soft fruits such as strawberries, raspberries, gooseberries, blackcurrants and redcurrants, as well as asparagus and peas. The ebbs and flows in the need for additional labour are accommodated by drawing on other family members. For instance, in reference to the fruit business, the husband outlines their strategy for coping with peaks in activity: ‘My mother-in-law looks after the sales. She weighs the fruit and takes the money for two months of the year. And we get on with the more serious side of the business.’ (Table 3.1, N01) The sense in which the routine management of this enterprise is described suggests that women’s labour is taken for granted. The affective relations that characterise kin relations, and in this case women’s labour, are exploited to service the needs of the enterprise (Baines and Wheelock, 1998). The advantage of this employment strategy is that family labour offers flexibility whilst not being constrained by the formality of the employment contract. Combining this strategy with capital investment in state-of-the-art farming technologies and a sensitivity to changing market conditions allowed them to expand their enterprise whilst cutting the number of direct employees to two fulltime workers. Despite the long working partnership, Mr B. still does not count his wife in the organisation: ‘Well, like every other business I have retrenched and I employ two fulltime hands and there is myself and my son. Yes the four of us do it all. I have a contractor in to harvest the sugar beet and I get the hedges done once a year by a contractor.’ (Table 3.1, N01) Following the downturn in farming, the enterprise has diversified into real estate development. One of their most important business investments has been the acquisition of valuable urban development land and they are currently seeking planning permission to build commercial premises. One of the most interesting aspects of this enterprise is the manner in which this business partnership used a dimension of their enterprise, 34 Class, Gender and the Family Business their interest in horses, to make new social connections. This eventually led them to enter a privileged social milieu, a manifestation and an affirmation of their social status. This initially involved running a livery business. This was a modest business, and although they limited the number of horses they stabled, it introduced them to the local gentry and a very prestigious hunting fraternity. As Mr B. explains: ‘We got very involved in the horse business and would have at the peak of the thing a couple of grooms here over the entire winter and maybe have a dozen horses for the family to ride, and you know it was costing us a lot of money. But we came into this hunting thing half way through our lives. This was a great advantage to the children and they made really nice friends. The people who were masters of the hunt, who by tradition were often titled and owned vast fortunes.’ (Table 3.1, N01) This conveys the sense in which business connections pave the way for social recognition. Symbolic of this was when Mr B. was made master of the local hunt. This example again raises the question of social recognition and, although Mrs B. points out, ‘And naturally J. made the most popular master they had for a long time’ (Table 3.1, N01), his involvement led to tensions in the partnership, which will be explored later. However, for him it symbolises material success, respectability and social esteem: ‘Yes, I think I can say that we raised our standards purely by leading the life we lead and the people we turned out to be. But, of course, we were fortunate enough in that we had enough money to lead that sort of life.’ (Table 3.1, N01) This comment suggests that the manner in which business wealth is spent is inextricably bound up with the social aspirations of such entrepreneurs, broadening the notion of investment, which in any case claims that such strategies are employed for the benefit of wider family interests. As opposed to reinvesting returns into the enterprise, this entrepreneur suggests that expenditure in conspicuous consumption was a rational choice, because it opened up social opportunities for the wider family members. Involvement in such a time-consuming leisure pursuit as hunting is intended to signal the affluence of the family. In Chapter 6 the issue of recognition and the manner in which this process is underpinned by sacrifice and gender politics will be explicated. Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 35 The next couple also started a business following their marriage. The principal activity of the company is the manufacture of specialist hygiene equipment and barrier protection products which are marketed on a global basis. In addition, the company has several European subsidiaries, two of which were acquired in the early 1990s. Like his peers, this entrepreneur started out with some advantages. First, his parents owned a second-generation business in the restaurant trade, which was inherited by his oldest brother. After his marriage he was given a fledgling business which consisted of a small plant and some machinery. Trained as a chartered accountant, he had knowledge about the financial aspects of running an enterprise. Although his wife played a key role in the establishment of the enterprise, she remains ambivalent about the value of her contribution. This woman is a graduate and completed graduate management training with a large high street bank, through which she acquired important skills. However, at the start-up of the business, in order to save money, she worked as a sewing machinist for a short time and began the production of goods: ‘The job that I did entailed a very, very simple sewing technique. It involved sewing a ‘mop cap’ where you zoom around the edges and you make a hundred of them and put them in a box. I did the first orders and got them out. I did that job for a short while.’ (Table, 3.1, N07) Unlike their spouses, wives typically give a very different account of their experiences of business start-up. This essential work is concerned with the operational aspects of the enterprise. For instance, it is the routine and practical features of managing the fledgling business, a crucial phase of the enterprise, that concern wives: ‘Yes I helped him in the beginning. I did a range of odd jobs like the banking, paying the wages. In fact, I seem to remember that I worked the first sewing machine that we had. This was before we employed anybody. After some time I had enough and I then started to recruit people. So recruitment became my responsibility. As the firm got bigger and bigger I took on more and more jobs.’ (Table 3.1, N07) This comment conveys the sense in which such women underestimate their own efforts. In this case it is clear that the wife was undertaking four very important functions: administrative tasks such as the banking, payment of wages, and staff recruitment, whilst also undertaking pro- 36 Class, Gender and the Family Business duction responsibilities. This suggests that the work that she was doing constituted the core operation. Such women often describe this range of functions as merely ‘helping out’ or doing ‘odd jobs’, which then can easily be construed as peripheral. By contrast, male partners in a similar situation draw on a different discourse to describe such activity. They rightly claim extensive knowledge of the business and emphasise the notion of sacrifice, which then signals commitment to the business and the family. The wives, on the other hand, in talking about the manner in which such critical times are managed, draw attention to the interplay with their domestic responsibilities. However, as this example illustrates, despite the organisation’s dependence on wifely labour, such entrepreneurial wives articulate a strong sense that necessity sustains them in such enterprise as opposed to any grander notion of partnership: ‘Well, the children all went to play school. When our last child was born it coincided with the wages and salaries being put on computer. Rather than be out of a job I got M. [spouse] to stay at home one day a week so that I could go and train to do the wages on the computer. And after a few weeks I knew how to do it, and I found someone else to look after the baby. But M. took a day off each week for a long time to enable me to do that. But then they had no one else to pay the wages so he had a vested interest. There were over a hundred people to pay. And if I was ill or something it was very scary because we just had to pay our people. I remember sitting up in bed having my last child with all the papers and pay envelopes all over my bed putting the money in. We just had to manage.’ (Table 3.1, N07) This comment illustrates the ambivalence and tensions that underpin the husband and wife business partnership. By insisting that she undertakes training, this woman is not only concerned with the functioning of the organisation; there is also a sense in which the new skill will safeguard her job and continue to make her services non-expendable. The husband’s co-operation is then rationalised as vested interest and business survival, as opposed to any ideal about partnership. These issues will be returned to in Chapters 4 and 5. Some of the ‘newly’ rich men benefited financially and very substantially through marriage. As a result, in some cases they were able to upgrade and expand their businesses, a tendency showing some parallels with the dowry1 system consistent with earlier capitalist development (Clemenson, 1982; Davidoff and Hall, 1987; Goransson, 1993). Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 37 Epitomising the stereotype of the self-made man, a flamboyant owner of a chain of 26 fast-food restaurants was able to extend and upgrade his business through marriage. He had started in the restaurant trade 20 years earlier with the aim of ‘modernising’ the British restaurant trade. He came from a poor American-Jewish family and, working as a doorto-door salesman, developed entrepreneurial skills at an early age and used these resources to finance his university education. He came to London with a clear vision of a market niche and managed to raise enough capital to open an upmarket pizza restaurant. Later, he expanded the business to a small chain of restaurants. The notion of status and class as a statement of material success is demonstrated for this particular entrepreneur when he took an interest in the life-style of the rural gentry. Having entered and built a social network amongst the local gentry in one of the Midland counties he set about creating the persona of a country squire. He rented a country cottage in the grounds of a country house, became acquainted with the owner, joined the local hunt and developed an interest in shooting. In the early 1980s his marriage to a wealthy heiress paralleled the expansion and upgrading of his business interests. Although he was a seeker of publicity and self-promotion, press reports failed to reveal the source of his financial backing when he purchased a sixteenth-century stately home for £3 million. The idea was to restore the house, which had 65 bedrooms, and reopen it as a country-style hotel. The wife’s role mirrored the invisibility and immobility of the sexual division of labour, because she stayed at the house and supervised the restoration work, leaving the husband free to manage his growing business empire. This project was near completion at the time of the research and failure to secure an interview with him accidentally led to the discovery of a business partner, his wife. She explained: ‘We met in one of the restaurants that he owned in London. I was there on a business trip and we discovered we had mutual friends. He phoned me later and we started dating. Anyway, he had seen the house while he was out hunting one day and thought of the idea for the hotel.’ (Table 3.1, N39) She became a major investor in this enterprise, and took on the responsibility for the restoration of the property. She is also a substantial shareholder in a civil engineering business, and in addition currently owns several farms in America. A graduate in business administration, on the death of her first husband she inherited the business and attempted to 38 Class, Gender and the Family Business manage it. Her understanding and explanations of the many difficulties she faced are based on male hostility to women in ‘their’ businesses. Remarking on her first husband she said: ‘A wife in a business was as welcome as a pirate on a ship. K. guarded his business like a pirate guards his loot’ (Table 3.1, N39). Leadership change is very problematic, but in these circumstances was made doubly difficult by her lack of preparation. The difficulty stemmed from her earlier non-involvement and lack of experience and knowledge. However, she stepped into her husband’s position and depended on the advice of her husband’s former advisers, whose loyalties could not be taken for granted. She argued that she adopted a new and more open management style, but found that this destroyed the trust that had hitherto existed amongst the senior management team. The company was later sold, but she retained 5 per cent of the shareholding, which made her a bigger entrepreneur than the ‘great man’ she is currently married to. As a result of this experience she has established an organisation encouraging the wives of ‘big business’ to become more directly involved. Her current business activities include commuting between the UK and America to manage her farms. Although her role as a major investor and senior manager in her new business partnership ought to reduce difficulties of access and acceptance, she argues that she faces the undermining effects of the lack of recognition as a proprietor and manager. Overshadowed by her husband, this woman was very surprised when an interview was requested with her. As she tartly commented: ‘Nobody knows I exist, I was most surprised you wanted to talk to me. He gets invitations addressed to Mr J. and guest. The hotel was distinctly his idea, he said, he did not want to do it without me. We were engaged at the time, and he took me to see the house and gardens, and he had to have the house. But of course, honey, it is his dream and my money.’ (Table 3.1, N39) Although this wife provided the capital for the business, this is obscured by her husband’s public image of swashbuckling businessman. This point is again somewhat bitterly articulated in the following comment: ‘Most of the people you ever see anything written about are, of course, the more flamboyant ones, and N. is certainly one of those. He is in the press all the time and so very often obviously people pick up on that. So really Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 39 in business it’s those kinds of people versus the quiet little wonders, the wives.’ (Table 3.1, N39) This example conveys some sense of the way the combination of entrepreneurial and domestic ideologies legitimise men as business innovators, whilst concealing a wife’s efforts. The route to business start-up is often very similar for entrepreneurial ethnic minority men, and they too can benefit financially from their marriages. In fact, marriages can sometimes be negotiated that promise opportunities of business based on notions of effort and worth. In this case, an Asian man of South African origin, having proved that he had entrepreneurial skills, was able to upgrade his business substantially and diversified into a much stronger economic sector. However, he also came from a trading family and had intended to go into business independently: ‘I came to this country in 1974 and I got a factory job to earn money. I had always helped my father with his business, so I was trained by him in buying and trading. Education was not for me. At the weekends I did some market research amongst the market traders and noticed that they needed bags. I also looked at the shops and found the same thing. My next step was to find a manufacturer who would supply me. I had £3,000 for investment and I used some of that to buy a van to deliver the bags. My outlay was not big. I needed only a space to store my supplies and then my own labour. My prices were very competitive. Gradually I gained customers, got bigger and better orders and built up a customer base.’ (Table 3.1, N36) Having built up a small but successful business, he explains how the intertwining of kin relations and enterprise led him to negotiate substantial investment capital with his family of marriage in a portfolio that included expansion into real estate: ‘After three years I wanted to go into manufacturing, so I sold the paper bag business, and I came to realise that packaging was important. So I decided to manufacture polythene and paper bags for a range of clients. But I left for a holiday in South Africa. I met my wife’s uncle and I explained that I was about to go into manufacture, but he began to talk about property. My response was, “For that you need a lot of money,” and he said, “Do something and we will see what we can do for you”.’ (Table 3.1, N36) 40 Class, Gender and the Family Business This clearly demonstrates that marriage and wifely connections can lead to business networks incorporating wider kin relations. Subsequently, he opened a manufacturing plant for the production of fashion packaging and appointed his wife as manager. Although he argued that his entrepreneurial wife had complete autonomy over the management of this enterprise, acting as ‘family head’, he blocked attempts made to interview her. She colluded in this, explaining that her spouse managed public relations on behalf of the overall enterprise. Symbolising business success, he also manages an ‘international investment portfolio’ including real estate from large and beautifully furnished premises, while his wife works as operations manager in the manufacturing unit, mirroring the stereotypical and gendered front-of-house versus backroom organisational structure. For some of the respondents the moment of business entry paralleled a crisis. Many of the newcomers were in business in East Africa and were forced to leave because of political instability there. Although they intended to go into business as soon as possible, their need to survive, coupled with labour market discrimination, meant they often took lowpaid, menial jobs. Other business entrants were studying in Britain and were forced to remain, often experiencing labour market discrimination. Despite this, some graduated from university and also completed management training schemes in the commercial sector, before going into business independently. Other newcomers benefiting from neither a business background, nor the advantage of education were more likely to have been longer in employment, and saw business as a way of escaping the disadvantages of low-paid work. Very often their entry into business was precipitated by a desire for independence and financial stability and security. What is interesting is that despite the presumptions of the Thatcher government and market economics, restructuring does not appear to have produced many new business entrants, for only one respondent, a former production manager with a large textile company, reported going into business after involuntary job loss during the 1980s. A second group, those motivated to make a change of life-style, often left the security of professional and well-paid careers lured by the challenge of succeeding in a business venture of their choice. There are marked class differences between these two groups. Most of the ‘newly’ wealthy on entering business had a link with their former area of business, or had a business background and/or appropriate skills. As I have argued earlier, this sits very uneasily with the theoretical literature on enterprise, which tends to neglect structural factors such as the economic climate and the availability of resources, such as the range Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 41 of inputs made by family women. There is another aspect to this which involves emotional support and the manner in which the dynamics of gender politics influence couples’ relationships in business partnerships. For both ethnic minority and white majority entrepreneurs wives very often were the catalyst and driving-force behind business entry. The entrepreneurial literature rightly highlights that entering business can involve an element of risk, but assumes that men are the natural risktakers. In contrast, the research suggests that wives risk the closure of their careers and make considerable direct financial investment in a fledgling business. It seems that wifely ambition can take precedence over family security: ‘I said to him, “People are like that, if you are doing them good . . . You are working so hard, putting in so many hours, and at the end of the day, you get a pat on the back. That’s your salary.” But if he went on his own, you know, whatever he put in, he’d get more out of it. I was in London working very hard, and my company offered me this Hong Kong posting. This was a big opportunity for me. He wasn’t keen on this, so I said I’d put my money with his and we would try to make a “go” of business.’ (Table 3.1, N17) Whereas the entrepreneurial and domestic ideologies suggest that ‘strong’ men take sole responsibility in the making of such major decisions, in this case there is little equivocation about the merits of business on the part of the wife and business partner of a rapidly expanding insurance business. The decision to go into business was precipitated by the wife’s improved career opportunity, which she drew on as a bargaining tool in persuading her husband to go into business. But even with his wife’s financial investment the husband recalls that he was much more doubtful: ‘In fact, she [wife] was instrumental in making the suggestion . . . and moral support is very vital . . . because if she had not accepted the idea of . . . because I had a very lucrative position. I was getting free pensions, free sickness scheme, a very cheap mortgage and absolute security. I was rather dubious when I left, but without the moral support I wouldn’t have been able to get through.’ (Table 3.1, N17) Both partners gave up their jobs. The husband had a business degree and was professionally qualified in the insurance business, had gained knowledge of the market and had access to clients whilst working with 42 Class, Gender and the Family Business a large national company. As a senior executive he was able to poach some of his former employer’s clients. These proved to be advantages in the earlier development of the business. The wife had many skills to bring to the business. She was trained in accountancy but failed to find a job. She then trained in computer software and found employment as a software engineer. She had been very successful in this, and her company had offered her a prestigious posting to Hong Kong. It was at this moment that her husband decided to make the break and give up the security of a professional career. But the husband does not say this in his interview, and compliments his wife only for lending ‘moral’ support. While wifely encouragement was important, to present his wife and partner’s efforts in this manner understates her contribution, for she became his business partner, investing her savings, abandoning her career, whilst offering her unpaid skills to their business. Using their savings they bought a larger house, a computer and other additional equipment. The mix of skills they brought to the business greatly helped them to succeed. Her tasks in the business partnership included administration, general management and dealing with clients. The arrangement of managing a business from home placed disproportionate burdens on the wife: ‘To run a business at home, yes, it was like a cattle market. The phone rang all times of the day and night. I had to deal with clients calling, whilst cramming in more and more work. Then, he’d have to go somewhere at a moment’s notice, which meant that I’d have to reorganise around that. He was out all the time.’ (Table 3.1, N17) At the same time it is evident that this joint venture exhibits an entrenched sexual division of labour, where gender defines mobility. Yet this form of organisation was conducive to early accumulation. They were able to keep operational costs to a minimum by using them home as an office, while the combined unpaid labour of both partners served as a mainstay until income was generated. The husband’s task was to secure clients and markets for their financial services. At this phase it would be fair to claim that each partner contributed different but equally important tasks in building the business. But it seems that the partners’ expectations of each other’s career development differs. This is intimated in the husband’s definition of his wife’s contribution as ‘moral support’. It is already evident that such distinct task allocation ties the partners into unequal career trajectories, a factor that creates Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 43 considerable tension in the partnership. This will be discussed in Chapters 4 and 7. Sentiment can sometimes be aligned to risk, as this respondent, the personnel director in a middle-sized textile business, suggests: ‘C. had worked for years with ABL, he was their production director, there is nothing he doesn’t know about that. Anyway the company decided to sell out, and he was made redundant and he got a sum of money. He then got a similar job in London and commuted daily. He lives and breathes work and I could tell that his partners were not pulling their weight, so just for him, I suggested we have a go ourselves. Personally, I wasn’t interested, I wasn’t career-minded, but I enjoyed my job. I had been the sort of wife who followed C.’s career around. Anyway, I said, “Let’s put our money together and make a 100 per cent commitment and go from there.” I am doing it for him, you see.’ (Table 3.1, N10) In this example the wife persuaded her husband to set up in business on condition that she became part of the process. But she sees the business as a way of compensating for the sense of loss her husband experienced through redundancy. She is currently personnel director, and whilst also acting as ‘welfare officer’, imposes a regime of strict patriarchal control on the mainly female factory floor. Her formal position within the business is director, and the way this is negotiated will be discussed in the next section. Some businesses were initially established on the strength of a wife’s technical skills and experience. It was on this basis that many clothing businesses were established: ‘We got married in 1968. I was working with my brothers. They ran a business and my mother had started it. We made shirts and blouses. Even my husband learned from them, I mean the cutting and other skills as he had worked in another place.’ (Table 3.1, N33) In this case the husband ‘fronted’ the new business. The wife’s family’s business had been in London and their marriage paralleled the couple’s business start-up. The manner in which this couple use their capital signals that women too make sacrifices in the interest of the business and is particularly evident during the start-up when enterprise has repercussions for the quality of life. In this case they used their capital to buy a house and converted one of the rooms into a workshop. They bought some sewing machines and other equipment, and, utilising the wife’s 44 Class, Gender and the Family Business skills, went into clothing manufacture from home. The geographical move from London to a Midland town facilitated a robust supply of cheaper ethnic female labour. Gender relations play a critical role in easing the difficulties in staff recruitment and the operational management of such enterprise, because all-women workgroups may be culturally more acceptable for some ethnic groups (Ram, 1994). In this case, the wife worked on the sewing machines and as soon as the couple accumulated some capital they used it to acquire commercial premises and were able to recruit local female labour. As the husband recognises, his wife became production and personnel manager: ‘I relied a lot on my wife. She was a skilled machinist and I had some experience in cutting and making, so we were able to start making women’s blouses and men’s shirts. As labour was cheap in the area we were able to offer women jobs. My wife taught them the skills and also supervised them.’ (Table 3.1, N33) The way tasks and responsibilities are divided between the partners emulates the examples in other sectors, for in this case the husband took the responsibility for marketing and selling their products and financial management. Yet there is a sense in which, perhaps unconsciously, the husband places himself as the nucleus of the activity and his wife’s contribution, however necessary, is still understood to be marginal. The apparent paradox of the centrality and marginalisation of female partners to the business is not specific to any particular ethnic group or business sector, but constitutes a pattern common across all groups and sectors. For example, franchising, a recent capitalist innovation in the service sector, reveals the same pattern. This example refers to a supplier of designer furniture and fittings to the retail sector. The idea for the business is based on a theme or image connected to a brand name. In this instance, the idea for the business was initiated by the female partner and she took responsibility for the initial start-up: ‘We were working for a manufacturing company in . . . AZ. We found it a little limiting. But we felt that it was appropriate to start a business. So on a new footing, and rather than put all our eggs in one basket, myself and Tom’s [spouse] two brothers started the business. We didn’t pay ourselves any salary and they lived at home. Tom stayed on with the manufacturer. We rented a very small office from our accountant with a desk and telephone and went on from there.’ (Table 3.1, N27) Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 45 This clearly demonstrates the significance of the invisible resources provided by the institution of the family in setting up this business, and in particular the role of wives in business formation. The ideology of dependency (Barrett and McIntosh, 1980) underpins such accommodation and is demonstrated in the manner in which the aspiring entrepreneurs drew on the ‘family’ as a material resource. The two single men continued to live at home and depended on their parents, while the woman relied on her savings and her husband’s salary. At the same time the ideology of dependency justified the eschewing of their need for an independent wage, and they were able to reduce costs by not paying themselves a salary. This and the other examples discussed suggests an emerging pattern of low entry requirement, with initial start-up outlay needing a small capital investment in office space, a telephone and two leased cars, which were used for the acquisition of markets. The availability of family labour is an important factor favouring the granting of a franchise (Felstead, 1991), and in this case several other family members, including the husband and father-in-law, later assumed senior positions with the company. Gender begins to have an important influence on the organisation of the business start-up, and the roles the partners played laid the foundation for the future division of labour. Most notably, the sexual division of labour is configured so that the male partners took responsibility for the marketing of the product. Ostensibly mobile and public, the men travelled, while the female partner assumed a sedentary, but crucial role, when she took charge of the administration of the business. Although this respondent questions her increasing marginalisation from the decision-making process, she draws on a discourse that assumes the transcendence of her spouse as head of the enterprise: ‘In some ways, I suppose, I represented Tom. I symbolised the business head. I had a career in marketing and sales and, I mean, I didn’t think it was a good idea to work alongside Tom. I wasn’t going to necessarily stay there. I was going to come in, sort out whatever needing organising. But I stayed on and then it became my project. It was just the right time. It started off with shelving and storage units and grew from there. Interiors became a designer thing. The next thing it was floors, partitioning, carpets, ceilings, the lighting and furniture. The idea is that you are presented with a shell and you kit it out.’ (Table 3.1, N27) Like many male entrepreneurs this woman describes the experience of her involvement with the early growth of the business. As soon as 46 Class, Gender and the Family Business income was generated they hired support staff. This example is distinct from the others, because it was not until after the business was successfully running that the husband and his father joined the business, the former as managing director, the latter as chairman. This event greatly changed the female founder’s position, casting her from a pivotal and vital role to one of marginalisation and disappointment. Although she had taken the risks and broken new ground, the husband moved in and took control once the preliminary work was completed. It should be noted that there is limited information about women’s contribution to the earlier phases of wealth formation for the category of ‘old’ or inherited wealth. However, other studies suggest that women were not just beneficiaries and consumers of their husbands’ wealth and contributed through the dowry system (Bourdieu, 1976; Clemenson, 1982; Davidoff and Hall, 1987; Goransson, 1993) and through their labour (Middleton, 1979).2 Conclusions This chapter argues that women’s contributions constitute an unquantified invisible asset behind many successful businesses, but that this is characterised in the traditional context as ‘helpmeet’ and ‘support’. The acceptance of this image reflects the gender stereotyping of wives in business partnerships, and as such both misrepresents and undervalues their contributions. In focusing on the different ways in which wives participated in the business start-up, through direct and indirect financial investment, the significance of their skills in specific cases and the variety of their labour inputs suggest that they constituted core elements of the business partnerships. During the first phase of wealth formation, the initial creating period, women’s inputs are both necessary and indispensable, for they are a source of cheap capital and free labour, both of which are presented in a manner that conspires in the construction of ‘his’ business. Male partners’ understanding of their wives’ contribution is contradictory, for even when they accept the importance of their wives’ efforts, this is overshadowed by a deeply entrenched sexual stereotyping, whereby they claim centre-stage and push their wives into the margins. This raises the question of women’s consciousness and indeed why resistance was not more generally spread. The position of wives in the family business is inherently contradictory. As the cases discussed illustrates, wives willingly and enthusiastically entered the business venture. But as Pateman (1988) argues, the discourse surrounding marriage Business Partnership and the Gendering of Wealth Creation 47 encourages notions of unity and partnership between marriage partners, and it should not be surprising that wives fulfil what they perceive to be conventional expectations. On the other hand, such women have an immediate economic interest in their husbands’ business activities. Husbands at this point also welcome their wives to the business. The issue for the wives is not that they contributed, but rather why they are not given recognition. This position circumscribes the character of resistance, because the pursuit of capitalist activity may well compromise their positions as wives. Given the contradictory circumstances they face, it is rational if they do not want to usurp their male counterparts, but rather want to be recognised for their own work. 4 Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation: ‘He also Wants a Pudding’ This chapter explores the career paths of husband and wife partnerships in the family firm. It examines the processes that characterise a general pattern of female kin subordination and male kin domination as wealth is accumulated in the family business. It argues that business growth has very different outcomes for wives and husbands in business partnerships. It will argue that male partners in parallel with the growth of the business are able to carve out careers as business heads and chief executives. By contrast, it will show that female partners are unable to make the transition from the stereotypical image of ‘helpmeet’ to company professional. The argument developed suggests that such women are systematically marginalised from the nucleus of organisational power and finally excluded from the family business. This is first evident when the business takes shape in organisation form with the introduction of bureaucracy, the formalisation of managerial structures and the specialisation of function. It will be suggested that it is at this point that the unequal character of the marriage business partnership magnifies the contradictions of the class gender nexus when attempts are made to co-ordinate the role of wife and business partner in the family enterprise. In highlighting the relationship between gender power and organisational power the chapter focuses on a number of partnerships in both ‘new’ and ‘old’ wealth categories. It shows that whilst not all wives are excluded from senior positions, women’s authority is neutralised in formal decision-making processes. Although eleven of the wives in ‘new’ business partnerships held directorships, they appear to tacitly surrender their influence over the strategic management of the enterprise and issues of inheritance. Illustrative of the women’s weakness is the finding that none of the seven working wives in the ‘old’ businesses, 48 Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 49 irrespective of the sector position, occupy a formal managerial position. This is most surprising since many of wives work in the landed sector where integration between home and the workplace may suggest an easier accommodation for the restructuring of the sexual division of labour in such partnerships on a more democratic basis. Yet the old hierarchies were, if anything, more rigidly intact. Turning to the ‘new’ businesses, for the eleven director wives this job proves to be a paradoxical experience, when such appointments parallel another pattern, the demise of women’s organisation power. One of the consequences of this is that the business in this phase of development means very different and unequal career trajectories for female and male kin. The debate about women and organisational power has very largely centred on the corporate sector. Of prominence is Davidson (1992) concern with the problems women managers encounter when attempting to enter the male world of the boardroom. The difficulties women face as career managers is also illustrated by Coyle (1989). She argues that they are in segregated sectors, such as local government and the hotel industry, where only 10 per cent of them succeed to senior posts. Grant and Porter’s (1994) study of the medium-sized business sector is also indicative of the limitations of women managers’ organisational power, because characteristically such enterprises have fewer employees. These studies convey the sense in which structured inequality creates conditions that limit women’s organisational power, but Grant and Porter (1994) interestingly observe that there is an incompatibility between women’s managerial approach and organisational structures. Women managers, they argue, lack authority. One of the themes that emerges from this literature is the notion of a separation between women’s power and authority in organisations. Wajcman (1998) examines women career managers’ organisational power. She argues that resistance to senior women managers is ubiquitous within organisations and that it stems from the uncertainty that their presence generates amongst organisational men and women. The effect of such ambivalence to women in power is that their organisational authority is considerably compromised. This argument has resonance with Savage’s (1992) earlier work, where he argues that although women have increasingly moved into managerial and professional posts, they have been channelled into niches requiring high levels of skill and expertise, but with very little organisational discretion. This raises the question: Why doesn’t expertise enhance female managers’ organisational power? 50 Class, Gender and the Family Business The acquisition of skill (Cockburn, 1983), credentials and professional status (Witz, 1992) has, until the restructuring of labour markets in the 1980s, been a rite of passage for men in organisational power, but in the last two decades appears to be less effective for women managers. This argument challenges human capital theorists such as Becker (1985), who eulogise women’s participation in domesticity. Becker, for instance, argues that women fail to make adequate investments in their labour power and so cannot withstand the competitiveness of the organisational arena. On the other hand, some studies show that theories of human capital cannot withstand closer scrutiny and that other factors come into play. Reflecting the tenets of dual theory (Walby, 1997), Witz (1992) shows that women’s attempts to improve their stock of human capital through credentials is often fiercely resisted. Similarly, Roberts and Coutts (1992) demonstrate that, historically, women’s entry into accounting has been resisted, and arguably there is a legacy to this, which is reflected in the stereotyping of women managers as incompetent in such areas as financial management. These arguments have a resonance in understanding women manager’s roles in the family firm. The chapter focuses on two women managers in the manufacturing sector, and suggests that the technical skill, tacit skills and entrepreneurial experience they had gained had little salience for career development. In the first instance, the success of the clothing enterprise hinged on the wife’s technical skills and managerial competence, and in the second case the production of hygiene products depended on the range of functions performed by the wife. In each case the women/partners worked full-time and managed shop floor operations that involved over 200 employees. In gaining such comprehensive experience these entrepreneurial wives typically gained many new skills, yet appeared to have not improved their status within the business. Expertise is used in the loosest sense to suggest that women managers cope by tapping into their own skill portfolio and a wide range of managerial competencies similar to those gained via a career profile comparable to their male counterparts. In this sense, as the enterprises develop and acquire new functions, such wife managers succeed in finding solutions simply by drawing on their reservoir of tacit skills and through the experience of doing the job. Whilst the first one remained a middle manager, the second eventually acquired the title of director. Savage’s (1992) argument has some salience in the examples illustrated, in that their expertise failed to expand decision-making boundaries for them. Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 51 Typically, such enterprise depends on women’s technical skills in machining and sewing, technical competence that is often inherited and handed down from mothers to daughters: ‘I was working in my mother’s factory in London. She started it and my brothers and I joined her. I then got married. We decided to expand the business and we moved here [Midlands]. I started the machining and after the factory got going I spent all day there, from nine o’clock in the morning until seven o’clock in the evening. When we first opened we realised that there were very many ladies sitting home doing nothing. Given that they couldn’t speak English, they didn’t work. Myself and a friend went out there and recruited them. It was easier for them to work for us as we spoke the same language. I trained them in the machining and made sure the orders were done on time, and they were properly finished.’ (Table 3.1, N33) This pattern of work organisation rests on the informality and inequality characteristic of affective relations, when such enterprising wives constitute the core of the production operations that accommodates the accumulation of profit and business growth. In this case, the wife organised the training of new workers and became a general manager. The second important dimension of such managerial roles relates to the question of human resources. The medium-sized businesses they managed were labour-intensive and drew on large numbers of female workers, many of whom came from ethnic minority backgrounds. Subsequently, the presence of female management proved to be an important recruiting incentive. Gender symmetry between managers and employees helped to smooth out difficult industrial relations issues that are partly cultural and patriarchal in origin in the routine management of the virtually all-female shop floor. Typically, one husband/partner pensively commented: ‘Well, my wife looks after the staff. As you can see many of our staff come from very different backgrounds and cultures. Having a woman in charge makes being here more acceptable to them. I mean she takes good care of them and will send them home if they are sick. She undertakes all of that in a way that I couldn’t.’ (Table 3.1, N33) This is a role befitting woman managers in the family enterprise. Drawing on female stereotypes women are assumed to have domestic skills that can be easily transformed into managerial competence in 52 Class, Gender and the Family Business specific contexts. This common-sense approach to wife/managers is part of a business strategy that cuts across ethnic divisions: ‘Well, I see my role on the very much on the personnel side of the business. In a factory situation like the one we manage here, it is quite important to have a woman on board. Aside from the recruitment role that I play I see my role very much from a welfare angle. Our girls have problems from time to time they need to be addressed quite promptly as this has implications for our output. I see myself as a hands on people person.’ (Table 3.1, N10) However, whether such women managers survive depends on the phase of wealth creation, which seems to be strategically determined and thus beyond the boundaries of female decision-making. For the restructuring of such businesses parallels the demise of the wife/manager’s job. For instance, in the case of business N33 the clothing manufacturing operation was sold and the money reinvested in property development and wholesale clothing. The move into more capital-intensive business led to a dramatic rationalisation of employee numbers and this rendered the manager and her niche skills dispensable and disposable. However, as the next chapter will highlight, the exit of the wife/manager and such sectoral shifting also witnessed two other events: the accumulation and stabilisation of family wealth and the son’s entry into the business. By contrast the hygiene company (N07) both upgraded and expanded its product range and increased market share, whilst opening international subsidiaries. Consequently, the business acquired more sophisticated bureaucratic structures with divisional functions. From the start the management of the business exhibited a sharp sexual division of labour. The husband, a trained accountant, took responsibility for the strategic and financial aspects of the business, while the wife took on the operational management of the enterprise, facilitating growth in the evolving structure. For instance, she coped with the rather ad hoc manner in which new functions emerged parallel with organic business growth. Adopting a hands-on approach, she assumed responsibilities as diverse as selection and recruitment of different staff categories, the development of payment systems in addition to implementing appraisal schemes. This rather all-embracing, hands-on role mirrored the entrepreneurial male model where, characteristically, male entrepreneurs and business heads are able to valorise their experience in ways that women are not. Consonant with Reed (1996), the research shows that men draw Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 53 on notions of effort, sacrifice and achievement to enhance their images and reputations as entrepreneurial men. By contrast, this particular wife/partner is uncertain about the value of her contribution: ‘By the time I was made a director of the company I had withdrawn and I wasn’t working there so much. I guess by this stage I was doing the personnel work. But then it got to the stage where I wasn’t viable anymore. The company had got quite big. It got divided into departments and each one had a manager. All that I was doing was of a very “hotch potch” nature. For instance, writing out a newsletter, and working out the profit shares, and holiday arrangements, and interviewing people and doing bits of public relations work. It got to the stage where each manager had his own department and preferred to do the job for his department that I was doing for it.’ (Table 3.1, N07) At a superficial level this comment might suggest that such entrepreneurial wives find it difficult to manage power and prefer the hands-on approach to tasks that are now delegated to functional managers. However, it might be expected that the position of director would of necessity require a closer involvement in the strategic management of the expanding enterprise, but this is the husband’s niche. It seems that although this woman acquired a new job title, the content of the job was unchanged and she tried to continue doing her old job: ‘So each manager wanted to interview his own staff and provide his own form of application or whatever. The computer department computerised the wages and salaries, so although for a while I worked on the computer I had to learn how to pay the wages and salaries using the computer. It became obvious that the computer manager – well, he was running the rest of the service and it was really only right for him to do that also. I became more and more dissatisfied because I felt that I’d got little bits of everybody’s job. I sat down one day and divided my job into twelve bits and gave it all away. I was left with an empty desk and I left. It was difficult for me to know exactly when to withdraw. But my skills were not particularly sophisticated and each manager developed a policy in his own department, and I didn’t feel that I fitted anywhere.’ (Table 3.1, N07) On the one hand, the lack of formal credentials seems to be the problem. Lacking qualifications she feels less professional compared to the new management team. However, it is rather ironic that wife/managers view their efforts and enterprise in such negative terms, for some 54 Class, Gender and the Family Business husband/partners, as the discussion in Chapter 6 illustrates, take immense pride in being ‘self-made’. Endorsed by masculine ideologies they confidently denigrate their formally qualified counterparts. With her old job distributed amongst a new team of managers she was unable to carve out a new role for herself. Comparing her skills with the new managers, she argued that she lacked a professional training and did not value the knowledge she had gained through experience. At this phase of wealth creation and business development that wife/managers begin to be marginalised. Not wanting to encroach on the functional managers’ work, she feels superfluous: ‘The biggest problem was that I was a director and yet in each area that I worked I tried to work underneath the manager. It was not viable to be a shareholder, a director and working underneath. They didn’t know if they could go against my decisions or not. I, on the other hand didn’t want to be making decisions which other people felt they should be making. So I felt uneasy. And anyway I though, “It’s his company”. I just wanted to do something on my own.’ (Table 3.1, N07) What is distinctive about this comment is that, echoing Grant and Porter (1994), there is a ‘lack of fit’ between her management style and the organisational hierarchy. What is not at all clear is why an organisation of the size and complexity of an international medium-sized firm is unable to find the founding partner a place within the strategic management team. However, one of the guiding principles of the husband/partner’s approach to the management of the enterprise is that family members should not be involved. For instance: ‘You have a choice in business and in the way you can run a company. You either keep it within the family which I think has severe constraints on growth. Or you can say, “I will develop the business and bring in professional managers”.’ (Table 3.1, N07) Whilst the thrust of this point has considerable validity, it is quite clear that this entrepreneur is happier with hired managers. This example is illustrative of the manner in which arenas of organisational power that involve husband and wife business partnerships are infused with gender politics in ways that are undermining for wife/partners. Very many wives, despite their inputs, feel that the business they have built together is ‘his business’. In such cases, wife/partners will find it very difficult to transcend the ‘helpmeet’ image of their managerial Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 55 inputs and to construct professional profiles. The example discussed above suggests that wife/managers in the family business face obstacles when they attempt to gain recognition as professional managers and to formalise their organisational power. The salience of Ram’s (1994) characterisation of working wives as de facto managers is that it aptly depicts the kinds of roles such women are expected to play. Although Ram fails to detect any gender conflict within the familial business arena, as the next example of a wife/ husband partnership in the hotel sector illustrates, the issue of lack of recognition and the formalisation of women’s managerial power remain highly contentious. Returning to the husband/wife partnership (Table 3.1, couple N39), as the previous chapter illustrates, this entrepreneurial couple used the wife’s capital to establish a ‘concept’ hotel, an investment that involved the buying and restoration of a dilapidated country house. The idea for the hotel incorporated much of her American spouse’s business and social aspirations. The husband had admired the lifestyle of the English gentry and had developed many connections with local families. The acquisition of the large house suggests inclusion within a particular class, whilst also being a symbol of considerable affluence. Modelled on domesticity, the management of this enterprise easily incorporates the idea of the ‘idle’ wife amidst generous hospitality. The intention is to disguise the commercialisation of the family home and the paying guests through the informality of the management system that so readily characterises the de facto role of such wife/partners. Unlike many of the other wives, this woman had organisational power and managed a separate aspect of the enterprise, the hotel, while her husband’s interests included the development of a chain of ‘theme’ restaurants in London and elsewhere. This may infer that the business partnership reflected a more equitable distribution of power, but the ideology of domesticity emphasised the traditional gender division of labour. The wife, now ‘lady of the manor’, stayed at home, whilst the spouse went into the marketplace to earn the money. A very flamboyant personality, the spouse attracted great publicity and credit, overshadowing his wife’s role. She argued: ‘I think with the hotel business the smaller ones are run by husbands and wives that have been started by themselves, but it is only the husband you see in the press. I mean it is never the women and they are quietly at home keeping the show on the road. I am here seven days a week doing just that. I just make the house run. I mean whether it’s the florist, I have to do 65 flower arrangements a day. I have meetings in the morning. I work with the 56 Class, Gender and the Family Business chef most days preparing for the special functions. Each day I do an audit, I make a list of things that are not quite right. In the evenings I’m up in the bar when I like to speak to the guests. It’s our approach to the business that we make the guests feel at home. You need a sense of flair and to be able to take care of people. The only thing I can say is that it is like having sixtyfive house guests in your home every day.’ (Table 3.1, N39) However, the balance of power for this wife/husband partnership was a contentious issue. This woman had business interests in the United States, was accustomed to transatlantic travel and high-powered meetings, but was ignored. The issue for this wife was the manner in which entrepreneurial ideologies link male effort with business activity in ways that overshadow the work that such wives do on an informal basis, while her money and success brought her no such acclaim. The problem is one of image management, where the claims for the husband’s role are exaggerated, while the wife’s efforts remain understated and in the shadows. But the whole idea of the enterprise rested on the husband’s self-promotion as a swashbuckling, shrewd and innovative entrepreneur, while the concept of the hotel with connotations of wholesome and rural homely pleasures, hinged on the ideal of wifely domesticity. And as the comment above illustrates, typically such manager/wives engrossed in day-to-day operations also perpetuate a culture of under-recognition. Neither credentials nor the successful financial management of the enterprise are accepted as sufficient evidence of competence for some husbands. Wives’ proven expertise in the financial management of the enterprise does little to save women’s jobs and careers. Some of the women who held financial directorships and demonstrated a sense of business awareness posed a threat to their roles in business partnerships. Referring to the franchise business discussed earlier, once it was operational, the wife became financial director. The management team also consisted of her husband as managing director and his father as chair man; his brothers were given directorships in sales. This seemed to work well: ‘Yes, it was great fun. We tried to keep tight control of the finance, and would only spend what we could afford, and we didn’t use our overdraft facility. We were very profitable on that basis.’ (Table 3.1, N27) Her approach to finance is cautious and this is incorporated into the system of credit control: Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 57 ‘This is partly due to the way we organise payment for orders. On placing an order the customer pays 40 per cent, another 40 per cent on delivery and 20 per cent on completion of the project.’ (Table 3.1, N27) On the one hand, this example typifies the management of finance at the operational level of the business. It is a relatively low-key but critical dimension of running a business, but is also indicative of a particular approach that has implications for the strategic management of the enterprise. On the other hand, as the discussion of the self-made man in Chapter 6 suggests, it bears little resemblance to the way such entrepreneurial men discuss the financial management of the business, which is often portrayed in a series of manoeuvres between players reminiscent of a chess game. However, her expertise was not enough to sustain her in the business, and through a rather tangled series of events, she found herself ‘eased out of a job’: ‘There is Tom, the managing director, and although the two brothers are directors they are basically salesmen and each has his own area to control. I mean, they can sell anything from £100 worth of storage containers to £300,000 of shelving and partitioning in an afternoon. That is the buzz for them. Then, of course, it is up to them to control their own area and they have to make sure that it is profitable, that they service customers and get new business. Quite challenging and interesting [pause] I’d say my job was more unit based. I made sure we were getting paid and keeping enough of money floating around without going into debt.’ (Table 3.1, N27) When the company was on a firm footing she became pregnant and took some leave. This example bears some comparison with business partners N07, in the sense that she was replaced by a newly recruited professional manager, but was called back to work earlier than anticipated when the new financial manager became ill: ‘My husband runs the company so the directors start with him. He is in overall control of everything that goes on and then beneath him there is Ray, the financial manager, and that was the job that I was doing prior to going for maternity leave. His job is really one of the most important in the company. He was ill and I literally came back at the drop of a hat. Of course, he got better, and that created a muddle, well there were two of us . . . Well, I have taken over the ledger, sort of a clerk’s job really. I do a bit of everything. I find myself perhaps involving myself where I am not wanted.’ (Table 3.1, N27) 58 Class, Gender and the Family Business Whilst this is consistent with Oakley’s (1987) argument that women on returning to work after childbirth experience a depreciation in their labour market position, other factors came into play, particularly the senior partner’s attitude. Summing up her situation, she felt that the substance had been removed from her directorship. Formally she had the senior position of director, but none of the status and power that accompany such a role. The role she had prepared for herself was allocated to another manager and there was no clear role for her. Moreover, her skills were underutilised and this may be in order not to appear to offer a threat to the financial manager, the husband’s ‘man’. This loss of power had wider repercussions, which became evident in management meetings when colleagues did not expect her to have opinions different from her husband’s, who demanded deference from her and the team. However, she contested his ‘autocratic’ management style, often openly disagreeing with him. But it was proving difficult to sustain the challenge, since she argued her allocation to more menial tasks undermined her authority. These changes were to have very negative implications for her self-worth. At the same time, her husband (the managing director) began to insist that she undertook a more thoroughgoing involvement in domestic tasks. She explained: ‘I need to be home by 5.10 now. S. not only demands his dinner on the table, but also wants a pudding.’ (Table 3.1, N27) This is an interesting example, for this woman had been the core founder of the business. Instead of basking in the glory and the construction of an identity, she was ousted by her husband who has replaced her as ‘head’ of the business and appointed a manager to compensate for the work she did. Her sense of alienation was also reflected in the ownership. It was divided between the three brothers, but the majority and controlling share lay with her husband, eldest son and managing director. According to this example, women’s display of professionalism cannot be but a poor competitor when faced with male kinship derived power and prejudice, anchored in a rigid adherence to traditional values. She explained that her husband deployed other home-based tactics; for instance, his refusal to participate in any child care led to her doubting whether their partnership – either business or marital – would survive. Double jeopardy best illuminates the dilemma such women face, and these examples give little currency to neoliberal theorists, such as Becker (1985), who neglects the question of gender power and the manner in which men insist their partners engage in the Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 59 ‘labour of love’. This example shows that wife/partners face two intertwined sets of oppositions. The first comes from organisational and class power embedded in systems of control; the second from the authority that marriage and domestic ideologies afford to male kin. In the contest over the division of labour, male/partners gain considerable leverage over their wife/partners by drawing on the plethora of domestic ideologies that underpin the prescriptive management of child care. Geared to the varying needs for labour and expertise in the family enterprise male/partners manipulate such domestic ideology to include or exclude their wives. An example discussed in Chapter 3, from the financial sector, where a couple established their business in insurance, illustrates the difficulties such wives face whilst seeking a professional role in the family business: ‘Yes, going into the office is great. But I can see after me doing all this . . . he is against me being there. At times I can see him thinking, “Oh no, I don’t need you now, you know, I have got my staff, and I have a partner working with me.” And I can see what he is thinking, “Go and attend to your kids.” So I’m there in the morning, and then I have got to run back home at two o’clock to pick up the kids.’ (Table 3.1, N17) Typically, this woman was formally a director, but in effect worked as a general manager. Her role in the company is being contested around the issue of child care. In safeguarding her place in the business this wife has drawn on the normative strategy of part-time work. But such a compromise reflects a diminution of organisational power, an arrangement which is accompanied by tensions and differences between the partners, for her husband adamantly stated: ‘I would love her to work full-time with me, but my children would suffer, and one of us has to be at home. I think she doesn’t need to work here, she has a property [very large house] to look after. So it is up to her to look after the invisible side of the family, and there she has got her own contributions to make.’ (Table 3.1, N17) This comment is a succinct illustration of the way in which men’s interests in the family and the business become difficult to reconcile with notions of enterprise, masculinity and inheritance requirements. The establishment of the business means a restructuring of the partners’ tasks; the wife must now engage in the recomposition of the domestic sphere, move to the backroom and ensure that the next generation of 60 Class, Gender and the Family Business potential heirs are suitably socialised, while the husband goes ahead in the business. This neatly conveys one sense of Hartmann’s theory in which there are contradictions between male interests and those of capitalism. The wife’s contribution, so necessary hitherto, is now dispensable, for the company has resources to hire professional labour. In this case, it is not the lack of professionalism on the part of the wife that is the problem, but rather the husband’s resistance to his wife devoting her time to work and his insistence that she should return to domesticity. Laying claim to the moral high ground and reminding wives of their domestic duties is a tactic in the quest for male recognition and the establishment of a power base at the head of the family business. It is the immediate result of men as husbands being able to channel their wives’ efforts elsewhere. This example shows the importance of the interplay between the politics of domesticity and capitalist activity giving credence to Delphy and Leonard (1992) who emphasise domesticity as the site for women’s subordination. On the other hand, several writers argue that this is part of the accumulation process (Veblen, 1949; Davidoff and Hall, 1987; Marcus and Dobkin Hall 1993), in that ‘idle’ wives reproduce the next generation of heirs. Such women are expected to engage in cultural practices that generate and reproduce an image of family bliss in keeping with the bountiful entrepreneur and euphemistically described by their partners as ‘invisible’ workers. The problem from the women’s perspective is inherent in their husbands’ perception of them as subordinate ‘helpmeet’ and the obstacles this poses to their developing an identity as a powerful professional and entrepreneur, and an equal colleague and business partner. At the same time, it shows the strength of female resistance, for, by glossing over the tensions and by going along with the part-time compromise, some women remain active in the business despite the hostility. However, less generously, this might also be interpreted as female collusion for such women, and the women studied had a clear advantage over most working women, since they could afford to buy child care and domestic labour, including cooks and nannies. In the cases discussed, the husbands’ manipulation of the politics of domesticity largely account for the exclusion of their wives. Another dimension in the process of female marginalisation and exclusion from senior managerial roles in the family business is the manner in which ‘new’ managerialism is gendered and serves to perpetuate gendered perceptions of skill. For instance, the normative pattern of the female managerial role is in middle and lower managerial jobs, when women/managers engage in a series of tasks that require a ‘hands-on’ Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 61 practical approach. This also reflects a division between intellectual and manual labour, when driven by business imperatives female kin are valued at particular intervals for bringing in the ‘visual angle’ as in the hotel business, ‘or the human angle’ in the management of other subordinate females. Placed in a hierarchy, such gendered competencies pale into insignificance when compared with the stereotypical male competence, the financial management of the enterprise. For instance, in the 1980s a husband and wife partnership established a successful fashion chain that supplies a niche market. This business is undoubtedly based on a concept and quite a particular approach to dressing professional men and women. The concept in this case cleverly manipulated consumer appeal for without the idea there would be no business. Combining ideas with finance suggests a complementary partnership. Yet speaking of his wife and business partner, a designer, and her input to building the financial side of the business, the husband said: ‘I look on money as something I have made. I don’t sort of say, “Oh I have invested X amount”, but I suppose it is part of the business. What I do with my money is to do with my expertise, my professionalism. I make mistakes and I get it right, and I think in a sense I try not to worry people around me. But if you can get me a better deal on the money, which if you were my wife, and you could do this, well I’d be talking to you. But I think it’s sometimes the scale of things, and is beyond their comprehension, when you take the sort of money I risk.’ (Table 3.1, N14) This suggests that such men emphasise the division of labour in husband and wife partnerships and will always claim financial leadership, which they insist is the most important input to a business. Claiming the credit for accumulating capital through prudent investment qualifies executive decision-making. However, at the beginning of his business career, this respondent placed his first wife’s and family’s security at risk by raising capital using the domestic residence as equity, so his wife was involved. The point he wants to make is that women lack any understanding of the financial aspects of business, and the strategies and negotiations that are involved in investment planning are well beyond their scope. Continuing to insist that financial management is a male prerogative, he grudgingly claimed that his resources accommodated his wife’s career: ‘By the time she became my [second] wife, she had been a designer in the business, and I’d built up substantial assets. So if you like she got on the 62 Class, Gender and the Family Business bus four stops down the road, therefore there was money available she never dreamed of.’ (Table 3.1, N14) Couched in paternal discourse he argues that her achievements are based on ‘his’ capital, which facilitated her progress. This shows how the entrepreneurial ideologies have become a resource to such men by suggesting that entrepreneurialism (the earner of capital) is to be more valued than creative skills. Financial leadership constitutes the hard core of business activity; all the rest is incidental. However, at the heart of the problem is the difficulty the husband found in having to work alongside a wife, who in the public eye earned equal prestige. It is at this point that husbands may come to perceive their wives as competitors and rivals. Interestingly, at the time of interview, his wife had resigned from the partnership and was appointed to a senior post in a large company, she was also in the process of divorcing the respondent. There is considerable rivalry within husband and wife teams as they both vie for power and recognition as entrepreneurial managers. Turning next to the farming sector business partnership (Table 3.1, N01), this resonates with the logic of the notion of ‘habitus’ and highlights the way in which men tacitly accept practices that render wives unequal in such business partnerships. This inequality is articulated in very many different ways, and the degree of wives’ participation in the enterprise simply reconfigures such relations of power during the phases of enterprise development. In this case, the couple established a large business in crop production which requires sensitivity to changing market trends and involves on-going and careful strategic decisionmaking in terms of choice of product. This working partnership implies little formality and absence of bureaucracy suggests a more equitable division of labour. For instance, this was the only interview where the spouse explained that his wife played a ‘very significant role’ in the business. However, the research revealed that the issues of recognition and effort are bitterly contested. In a comment over recognition she argued: ‘That was the same with the hunting job. G. [spouse] was Master all the time and I did the donkey work at home. I didn’t get any recognition. Yet, I got all his horses ready and prepared them and did the hard graft. Yes, you do resent it.’ (Table 3.1, N01) This couple are very involved with racing and hunting, and the significance of these activities are that they are statements about business Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 63 success and social status. Fraternising with the local and national gentry through their leisure activities in racing and hunting are both the rewards and recognition of hard work and success. Characteristic of the entrepreneurial man, this farmer is the focus of media attention as a successful farmer and hunt master. The former leisure activity has, according to Veblen (1994), an honorific status in addition to being an insignia of consumption. However, the idea of leisure was forcefully challenged by his wife who resentfully conveys that she does the hard work. The husband had much more leisure time than his wife even during busy periods. The wife’s anger stems from the lack of recognition as a hard-working partner. Nevertheless, she continues to labour at home in order to free her husband’s time to hunt, because this signals ‘their’ affluence and sustains their social status in the community. This shows that wives compromise their autonomy within such partnerships in the interests of their class and status, whilst such aspiring men and their affectations of grandeur are part of a social process that suggests upward mobility and hints at membership of the gentry. Arguably, private enterprise and in particular family farms can be conceptualised within the notion of uneven development, and are thus a direct legacy of domestic production. It is sometimes argued that the unity between home and work afforded a more democratic division of labour within domestic production. On the other hand, Middleton (1979) suggests that the participation of female kin in the production of use-values simply reconfigured domestic power hierarchies and decision-making structures. This argument has significant resonance for this study for it appears that the scope of wifely involvement in management tasks and apparently nominal director positions cannot be read as indicative of organisational authority. The exploration of such an unequal partnership raises questions about the character of decision-making. For instance: Q. ‘Would you say you make decisions jointly?’ Husband: ‘Yes, we discuss anything of importance. Yes, that’s right.’ (Table 3.1, N01) Although the husband does not claim that decisions are made jointly, he qualifies it by saying that anything of importance is discussed jointly. His wife and business partner disagrees: Wife: ‘Well, not particularly. I suppose I have always had this niggling regret that I have never had my own life and you never get recognition for 64 Class, Gender and the Family Business yourself which I have resented. You get things like the stewarding, G. got made a steward ten years before I did. And that was because he was a man, I was doing more with the race horses and other things. So you know you are not your own person.’ (Table 3.1, N01) As Chapter 3 explains, this woman works on the farm undertaking a wide range of activities that includes domestic work. She argues that her duties in an uneventful typical day incorporate anything from tractor driving to cooking dinner for guests. Listening to his wife’s comment, the husband tellingly inquired: ‘You mean the fact that you are married, you are not your own person?’ (Table 3.1, N01) Typical of many other business wives, this one also envisaged greater autonomy in a career outside the family business. This implies that free from the constraints of the marriage institution, such women would ideally pursue a career of their choice: Wife: ‘Well, if you are married and got your own job, you will see a difference because you are recognised for what you are doing yourself, whereas things that are probably done here, it’s always the man who gets the credit.’ (Table 3.1, N01) This comment implies that it is the institution of marriage that rewards men for the effort they have appropriated from their wives. The sense in which the effects of the nature of power within the marriage and subsequent inequalities remain contested but essentially intact is explained in the notion of habitus. In this sense, both partners have internalised a common-sense approach to the way social structure relates to them as wives and husbands. In this case, it is not the husband’s power of decision-making over who should go hunting, but rather society’s preordained role for men and for women as husbands and wives, and the manner in which they subsequently engage in discursive practices that appear to confirm such expectations. There were seven husband and wife partnerships in the ‘old’ or inherited business sector, six of which were land-based, whilst one wife was a senior partner in a medium-sized food manufacturing enterprise. From the working wives’ perspective the difference between these businesses and the ‘new’ sector is that such enterprises were already established Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 65 and in some cases other family members were appointed to senior managerial roles. Aside from the farming sector, the fact that only one wife in twelve businesses managed to secure a job within the firm is suggestive of the difficulties the women encounter when attempting to enter such arenas of organisational power. Wives’ absence from the ‘old’ businesses is consistent with the patterns of female exclusion characteristic of ‘new’ enterprise. Exceptionally, in one case a wife became head of sales and her responsibility is to increase market share and sustain existing business contracts. She is also responsible for public relations. Prior to joining the family enterprise she had independent experience in the business world when she set up and managed her own enterprise. She argues that this experience is of paramount importance since it helped her gain confidence and self-esteem. Whilst working as a sales manager, her position within the enterprise appears to be secure, yet like other wife partners, she thinks that her achievements are taken for granted by her business partner: ‘Officially I am sales executive but I can’t make any major decisions. I recently won us a large order with an important new client. I came back to report to J., and he left the project entirely in my hands. Although he seemed pleased that I got such a big order, he never said so.’ (Table 3.2, O18) Women who have married into the family business and who have subsequently joined the business as managers feel isolated; indeed most wives were not at all involved with the business. Regarded as outsiders, such women report disapproval and resentment from other family members. ‘This year there has been a huge growth that I feel I am responsible for. I don’t get any recognition at all for this from J.’s brothers and the small amount I get from J. I have to cope with in my own way. My mother-inlaw knows nothing of the business and feels threatened by me. My aim is to stay in the business for a few more years and then move on to do something for myself, because there are too many family who do not appreciate what I do here.’ (Table 3.2, O18) Wajcman’s (1998) finding that the presence of senior women managers causes uncertainty in the corporate sector has some resonance for this example. Having gained a responsible role in the family enterprise, this 66 Class, Gender and the Family Business wife is regarded with suspicion and disapproval by other male and female family members. That such wives are misunderstood and isolated in managerial roles can be understood in the context of this comment, which shows that the business is not the enterprise anticipated for wives. In keeping with tradition, such wives should remain outside the business and, in the words of an earlier male respondent, are obliged to take responsibility for the ‘invisible side of the business’ – bringing up the family. In Kanter’s (1977) much venerated study, it is suggested that the problem is one of inadequate socialisation, in that corporate men have not accepted women as their equals and peers. She argues: ‘Men at the top, who may have never thought about a woman as a peer and feel vaguely uneasy about it, are not necessarily part of a conspiratorial plot to keep women from power. The dynamics of tokenism – the effects of limited numbers of women – make the women who enter ‘men’s worlds’ operate at a disadvantage. And what men think about women’s potential as workers and leaders may be honestly based on the women they know best: their secretaries and their wives.’ (Kanter, 1977: 264) This suggests that corporate men need to think about women managers differently. Certainly, this is the case, but Kanter’s rather sanguine approach ignores the crux of the problem, which echoes Collinson and Hearn’s (1994) argument. As the evidence in this study strongly asserts, men as men have an interest in the exclusion of women from organisational power. For such entrepreneurial men it is a concern with the proper socialisation of children, the potential heirs of their businesses, their reputations and their mortality. None of the six women in the land-based businesses held a formal position, and were therefore less likely to be included in the financial management. Typically, the proprietor of a large estate justifying the fact that the management was the exclusive responsibility of himself and his son and heir said: ‘Money and business matters I only ever discuss with A., the others [wife and three daughters] only come to me when they want money, or to borrow some. But with A. I discuss everything.’ Interviewer: ‘But I understand that your wife takes responsibility for opening the house to the public. Is that not part of your total enterprise, and does it not involve a financial input?’ Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 67 ‘Yes, I suppose it does really. Yes, and she does a lot, so I guess she ought to be here to talk to you today, and she’d have something different to say.’ (Table 3.2, O04) On the one hand, this conveys the sense in which wives and their contributions are taken for granted – wives are still perceived to be merely ‘helpmeets’. Teasing out the fate of such managers suggests that their survival is largely contingent on the strategic direction of the enterprise, the phase of wealth development and the sophistication of the organisational structure, in addition to the women’s aspirations and visions of the tasks in hand. In providing management skills appropriate to predominant female, labour-intensive shop-floor operations, such women are pigeon-holed into particular niche areas of expertise within the family enterprise and this has a certain resonance for Coyle’s (1989) argument. Conclusions This chapter argues that gender power plays a critical role in influencing the dynamics of organisational growth and the career opportunities within the family enterprise. As income increases it is invested in commercial premises, and in the hiring of support and professional staff. The phase of establishing the business as an operating unit of capital, an employer of labour and the formalisation and professionalisation of positions has implications for the wives. The problem for the wives in such organisations is that they experience great difficulties in making this transition from being seen as merely ‘the wife helping out’ to gaining recognition as a professional. The cases outlined above constitute the dominant patterns for working wives within the family business, when their expertise is devalued and their career progress is blighted by the dynamics of organisational power. Illustrative of this trend is that when wives do enter the boardroom they not infrequently face coups, sometimes engineered by their own husbands. While working women regularly encounter gender discrimination in the workplace, these women face additional gender obstacles, for the position of a working wife within the family structure brings in kinship structures, which very much circumscribe the character of resistance. The wives resist, using two distinct patterns that includes resignation and exit, and the manipulation of organisation power. First, as in the case of N07 (Table 3.1), such wives valuing a career anticipate male hos- 68 Class, Gender and the Family Business tility and leave the business of their own accord, to establish themselves in separate careers. In this instance, the wife resigned from her position as director, and, having trained in law, drew on her business contacts and took up practice with a local firm. The second pattern to emerge is one where women appear to survive in senior positions working alongside their husbands by fostering a public image which grants the husband the pivotal role (Table 3.1, N10). On the other hand, it is no small coincidence that the couple’s business is in textiles, where female management is almost indispensable. Whilst adopting this strategy it is likely that such wife/managers will be tolerated for as long as they are deemed to be needed, and there are no major changes such as expansion and/or sector shifting. In these cases, depending on the type of business, they take on managerial roles that are said to bring in ‘the female angle’. For instance, in the hotel businesses they have responsibility for the ‘visual aspects’, or in textile manufacture, where they take on supervisory and personnel tasks. Another important dimension to this pattern is where the wives acquiesce in the traditional supporting role, but this is perhaps more evident in the landed sector (Table 3.2, O03–O09). In a few cases in the ‘new’ businesses female kin take on stereotypical female roles such as secretaries, when some of the older first-generation entrepreneurs employ their daughters as personal assistants in the construction business (Table 3.1, N32). However, as this particular enterprise reveals, even such traditional bastions of male power relent under pressure. In this case the younger daughter, with the help of her eldest brother and against other male kin opposition, became the director of property investment (Table 3.1, N32). Generally, the sense in which the work that wives do as managers in family businesses is portrayed as peripheral is consistent with Ghillone’s (1984) analysis of the gender relations in the corporate sector. She argued that the largely female public relations department was perceived to be marginal. Subsequently, management refusal to upgrade and promote the women employees. On the other hand, the cases discussed are examples of contests about who gains power in the family business. The problem for the male partners is that they are unable to resolve the contradiction of accepting their wives as equals in the workplace. At the same time, the transformation of the wife as a professional is antagonistic to entrepreneurial masculinity which is rooted in both the business and the family. Wives must remain wives, either as ‘trophies’ or as ‘supports’, playing an essential but non-threatening or invisible role. Kanter’s (1977) study of corporate gender relations is a striking example of how the male executive Gender and the Management of Wealth Accumulation 69 career rests and is embedded in particular permutations of wifely support. Kanter (1977) argues that although the wives are not directly employed by the corporation, their social activities, behaviour and image are still bound by corporate culture and duty, and they are obliged publicly to demonstrate appropriate support for their husbands. Finch’s (1983) detailed work on the careers of professional men offers another interesting perspective on what might constitute wifely support. Finch (1983) argues that professionals in the public sector depend and draw on their wives’ unpaid services in the performance of their duties. Drawing on Pateman’s (1988) premise on marriage as the framework for male control of female labour and sexuality, the cases studied suggest that husbands do attempt to direct the course of their wives’ labour. The legacy of coverture (Holcombe, 1983), and the insidious idea that the person of the married woman in some senses belongs to the husband, continues to have resonance. It is this factor which enables husbands to attempt the regulation of their wives’ labour, accepting them out of necessity, as in the traditional context of ‘helpmeet’ during the phase of wealth creation, later attempting to push them back to wifely concerns. As this chapter has shown, during the second phase of wealth accumulation, the growth of the business accompanied by management boards, symbols of power, marks a potential change in the status of wives in the organisation. It offers them an opportunity to become professionals in the public world, the arena of power, but they are stymied by male hostility. The women are either marginalised from decisionmaking or excluded from the business, and this has implications for the issue of female ownership, since they are unlikely to have much influence in decisions about inheritance. The important question to ask is, does this also explain their scarcity as owners of capital? 5 Gender and Wealth Preservation: ‘I’m Not a Member of My Husband’s Family’ This chapter examines questions of business ownership, the conservation of wealth and gender power in the family firm. In particular, it focuses on the relationship between primogeniture, the conservation of established wealth and women’s exclusion from ownership. It argues that primogeniture accounts for the exclusion of female kin from ownership. The culture of primogeniture (Thompson, 1976; Clemenson, 1982) refers to the practice of impartible1 inheritance and is characterised in the practice of passing on the core unit of productive capital, the family firm, or estate intact along the male line to the eldest son. This chapter suggests that although it is rooted in and is a legacy of the landed sector, it is part of a wider class strategy that is principally concerned with transferring and safeguarding wealth. Exclusionary in character, it circumscribes women’s rights to property and is widely practised by the families studied, regardless of sector. Engels (1972) argues that this feature of female subordination is also manifest in the different class positions of the spouses, husbands being in the ruling class, while wives are more properly located within the working class. Whilst recognising that there are some important material differences between workingand middle-class women, nevertheless, like working-class women, female kin too work in the family enterprise and rarely acquire ownership. The concern of this chapter is to challenge women’s invisibility in patterns of ownership characteristic of wife and husband business partnerships, and to suggest some of the ways wives are bypassed by inheritance practices. This argument has some resonance with Delphy (1984), who locates female subordination within the household. This study found a persistently disproportionate distribution of business ownership amongst women and men. Consistent with convention 65 (93 per cent) of the businesses were registered under a male head, 70 Gender and Wealth Preservation 71 whilst five (7 per cent) were registered under a female head. The research found that for the future, regardless of the age of the business and sector location, in most cases owners will continue to be bound by convention, making sons the principal beneficiaries of such wealth. The persistence of such gender inequality through ownership was confirmed earlier by Wedgewood (1929), who examined inheritance patterns for 99 estates, and found that only six businesses were inherited by women (Wedgewood, 1929: 132). In the case of privately owned businesses the dominance of men in patterns of ownership suggests that a particular strand of masculinity and capital are two sides of the same coin. The tendency is towards impartable ownership exemplified in the male dual role of business and family head, when such men are either sole owners or the major shareholders. This embodiment of capital and male power places the destiny of family members within the parameters of male discretion, because families, like other institutions, are hierarchically structured, and although the ‘places’ in such configurations are sometimes contested amongst kin members there is a strong tendency towards conventional ordering. In this context, an uncritical acceptance of such patterns of male ownership conceals the convention that inheritance strategies traditionally have been used to prevent female kin from inheriting the productive portions of units of family wealth, except where there are no suitable male heirs (Thompson, 1976; Clemenson, 1982). Although, these writers appear to assume that such gendered exclusionary practice can be accounted for in the logic of male power, it would be equally valid to argue that it stems from the logic of particular capitalist formations. In this sense, the family business is a coalition between men and enterprise and is one of the most effective institutions for the initiation and preservation of wealth, for it combines the particularistic interests of the ‘private sphere’ with the ‘rationalist’ logic of the wider economy. Owners using the same strategies continue to reproduce the same conventions by excluding wives and female blood relations, i.e. daughters, from the core wealthholding. In this sense, the majority of business heads said they would not consider making their daughters the major beneficiaries of core productive capital unless there were no sons. Although girls born into such business families benefit through their class status in terms of education and life-style, and therefore are not entirely disinherited, the general expectation is that their life destinies are most likely to be experienced outside the business. By contrast, although wives’ destinies are defined within the parameters of the busi- 72 Class, Gender and the Family Business ness, they are similarly excluded from inheritance. For instance, there was not a single instance where a husband/partner said that in the event of their death, they would transfer their business interests to the wife. However, Thompson (1976) shows that, historically, wives, in some circumstances, were the ‘beneficiaries’ of core property, and were protected by the manorial law of freebench2 which gave a widow rights of access to her husband’s lands. By contrast, the research found no wife heirs, except in one case where the wife had begun an equine business and developed it into bigger enterprise after the couple’s marriage. In this case there were no sons and the husband predeceased his wife/partner and thus she became the sole owner of the business she had created. In nearly all other cases primogeniture seemed to be a convenient instrument for the exclusion of wife/partners from ownership. This is despite the fact, that, of the cases we know, and in addition to their labour contribution, eleven wives of the 44 ‘new’ businesses (Table 3.1) and four wives of the 19 ‘old’ wealth couples (Table 3.2), brought capital into the marriage and thus into the business: ‘I came into this marriage financially independent of Bob and I have maintained total independence and maybe too much so. He had already started the restaurant chain that was his business. As far as Swallow Hall is concerned, we certainly did it hand in hand right from the start. I have been financially involved with all his businesses, in terms of my investment. Since I am involved in a monetary way, I feel I have a bigger role, and at least as many rights as any other investor, but being the wife, you know it’s “I’ll take care of it for you”.’ (Table 3.1, N39) This comment is illustrative of the ambiguity and informality surrounding wives’ sense of ownership and the rights accorded to them as major investors. Such wives view ownership through their spouses, but the sustaining concern is that their investments in the family enterprise do not necessarily guarantee them equality in the management of the business. Typically, the paternalism that stems from the marriage relationship sullies what is also fundamentally a business arrangement, for as Chapter 4 shows, this wife assumes a subordinate role, acting as a middle manager of the enterprise. However, she is apparently reluctant to challenge the limitations of the status of nominal ownership. In the case of the ‘old’ business sector, where wives were not directly involved in the business, two wives had a minority shareholding. One Gender and Wealth Preservation 73 wife, who married into a fourth-generation manufacturing business, was given a gift of 10 per cent of the shares at the time of the couple’s marriage, but, as we shall see, this has strategic implications for the financial management of the business. ‘New’ business reveals the same exclusionary pattern, because although women contribute to the creation of the business, they are denied ownership and control. For married women generally there is a sense in which ownership is in name only and is mediated by their spouses, thus curtailing possession rights unless a nuptial contract states otherwise. However, the research found that, according to the character of the property, the pre-nuptial agreement is more likely to safeguard the valuables the wives bring to the marriage (Erikson, 1993). The problem with nominal ownership is that it discourages the active participation of wives in the management and the disposal of such business wealth. Of course, the meaning of nominal ownership can be explicated in the ideology underpinning the notion of ‘oneness’ of the married couple (Pateman, 1988), where the role of the wife disappears in the representative role played by the executive husband. The first strand in the exclusion of wives from the ownership of core wealth lies with the issues of male lineage and primogeniture. Thirsk (1976) argues that since the sixteenth century male primogeniture has been widely practised, particularly by the English aristocracy and began to be emulated by the middle classes in the nineteenth century. The emergence of industrial capitalism facilitated rather than impeded the practice, for the rationale was that younger sons would have other opportunities, whilst daughters would be endowed with moveable property and transferable wealth. With these kinds of reservations it bestowed outright ownership preferably to the eldest son, and was intended to safeguard the core family wealth. Nevertheless, where applicable, the law of freebench generated some opposition, since it granted at least one-third of an estate to the widow and thus was seen to endanger the survival of the unit of capital, and the particular lineage. Aside from the alleged financial risks associated with widow ownership, it was also disliked, presumably because it could lead to the transfer of the property to a different lineage via a second marriage. The advantage of primogeniture to both aspiring and established powerful male dynasties is that, as Goody (1976) argues, it ensures the survival of the lineage, in addition to safeguarding the business. The owners of the inherited businesses believe that primogeniture accounts in part for the survival of the family’s wealth. For instance, one of the landholders argued: ‘I mean, another reason a lot of these 74 Class, Gender and the Family Business families have survived is that the eldest son has inherited everything.’ In this case, a landowner with 3,000 acres, a country house, family homes in London and France, and a developing property business suggested that primogeniture is one of the principal means of sustaining family wealth and is a ubiquitous practice amongst such business owners. The responsibilities of such beneficiaries are at least to pass the unit of capital on to the next generation of the lineage, preferably having enlarged it. This point appears to be borne out by Wedgewood (1929: 164) who writes with reference to an industrial enterprise: ‘There is no doubt that, in the course of a few generations, the institution of inheritance has frequently enabled a reasonably thrifty and industrious family to turn a small original capital into a large fortune.’ This used to rest on skilful estate management, but such enterprise now needs to be managed with a similar degree of entrepreneurial acumen and astute financial management as any other business. This entrepreneur is professionally trained in estate management and is also a chartered surveyor, work that he continues alongside the management of his own business. In this case, the estate dates back to the sixteenth century when the family bought a landholding that they expanded with profits made in the wool trade. Some of his ancestors extended the family wealth by entering politics and by making judicious marriages. Since then the landholding has diminished in size but this can be accounted for by the poor management skills of one of his more recent ancestors. This suggests that primogeniture is accompanied by considerable risk, since it places enormous power in the hands of one person. Without the constraints of trusts irresponsible beneficiaries can squander large amounts of capital. In the case of this family, it is part of the duty of the current heir to resist profligacy and to make good the losses incurred by earlier generations. The survival of such a business in the current climate largely depends on the entrepreneurial ability of the beneficiary to adapt the business to market conditions. This means that new uses need to be found for the estate’s considerable assets. For instance, the estate consists of several properties, including a manor house and various cottages which define the parameters of the local village. These are being invested in and developed with a view to entering the luxury rental market. Other aspects of the estate are being commercialised, such as the woodlands which offers game shooting. The diversification of the enterprise into property development is considered a good investment and is more likely to generate income to help Gender and Wealth Preservation 75 sustain the enterprise. Shifting what were previously private leisure activities into the public market typifies the way in which the financial management of landholding has changed. Yet although such businessmen are willing and able to accommodate the economic and financial transformations consistent with the wider economy, they rigidly adhere to tradition in relation to domestic matters. For instance, the continuance of lineage remains important, and this landholding entrepreneur envisaged that one of his sons would become the major beneficiary. The importance of this example is that it provides the context in which to convey some sense of the way partner/wives who are also directors can be excluded from ownership. The title of director resonates with organisational power, yet female directors who have been the backbone of the family enterprise can be overlooked when wealth is transferred across generations. Referring to Table 3.1, couple N33, we see that despite the fact that this mediumsized business was largely established on the wife’s expertise in garment manufacture and on her competence in plant management, she lost her position in the business. After the company became profitable, its activities were switched from clothing to commercial property, which now constitutes the core of the business. This had repercussions for the partners and, as the wife explained, it paralleled another event: ‘The property is a completely new company. I leave that to him. My son has finished college. He doesn’t want to go to university. He is going into the business, and he will take over.’ (Table 3.1, N33) The shift from clothing manufacture, a principal area of ethnic minority business, into property development marks an important phase in the development of this enterprise. The logic of this move is twofold and has gender repercussions for the question of inheritance. First, it excludes the wife from ownership, except in a nominal sense. Second, the transfer of capital establishes, in instances such as this, the male line of inheritance by including the son in the ownership and management of the new business. What seems unfair from a gender perspective is that the wife, having contributed to the accumulation of a sum of capital, loses possession apparently through a business decision that involves investment in a different kind of enterprise. The implications of this would become explicit only if the wife director were to contest the decision or in the event of a divorce. However, domestic ideologies suggest that in any case such business tactics are conducted in the wider ‘family interests’ which are assumed 76 Class, Gender and the Family Business to incorporate the wife/partner’s interests. Indeed, from a business perspective and subject to the contingencies of the wider market, investments such as this into a more capital-intensive sector of the economy are considered to be more judicious, secure and to offer greater returns. However, shifts of this sort dramatically affect work organisation. In this case, the shift into commercial property means that the new enterprise will require fewer employees with different skills that are incompatible with the kind of management role played by the wife/manager. Although this represents upward mobility for the business family, it essentially marks the wife’s departure from the new business activity. Typically, examples such as this show that gendered kin relations are highly influential in the transmission of ownership, when the mother, a partner in the family enterprise, agrees that the chosen heir will become the major beneficiary of the new and better business. By ensuring lineal survival, primogeniture smoothly transcends the link between wifely entrepreneurialism and direct ownership in favour of the eldest son. In both ‘old’ and ‘new’ business sectors, although wife directors offered little resistance to conventions over the pattern of ownership, they nevertheless found ways to eschew the limitations of their lack of control. In a minority of cases, such women chose to resign from their positions in the family business and pursue a separate career. Turning to the hygiene company discussed earlier, the wife/partner played a major role in the early phases of business formation and became a director, which suggests that she may have a considerable stake in the enterprise. However, her reason for leaving the business is complex: ‘Well yes, I have a 10 per cent share, but really I have never sat down and thought about it or what it means. You see, I always saw the business as Richard’s. That’s his baby through and through. I have a career outside of that.’ (Table 3.1, N07) Ownership appears to mean very little to her. Like other wife shareholders it seems unlikely that she will seek possession of her shares. Her comment also implies that the business has more meaning and depth for her husband and extends beyond material possession. The issue for this woman is independence and the satisfaction of working towards a successful career external to her husband’s enterprise. Working as a lawyer she is able to earn a considerable salary, but has benefited from her close association with the business, for it is a client of the law firm of which she is a partner. In cases such as this, female kin are able to Gender and Wealth Preservation 77 draw on their family’s business networks in ways that benefit their careers. It has been shown earlier that many of the ‘new’ businesses are more likely to diversify, suggesting that the logic is to create wealth as opposed to establishing a particular kind of enterprise. This business, on the other hand, has witnessed considerable growth and has established international outlets and may, therefore, depending on the vagaries of the market, survive in its current form for a considerable time – a development that may encourage the founding entrepreneur to emulate the Penrose (1980) model of entrepreneurship. Emulating the ‘company man’ and the idea of establishing the business based on a particular product also contains the seeds for the development of the lineage embedding a purpose, and an identity and place in the world that symbolically guarantees the mortality of such founding entrepreneurs in industrial societies. The manner in which gender power stealthily pervades ownership within the family business is explicit in the case of the shop furnishing business (Table 3.1, N37). The wife, with the help of her husband’s brothers, had started this. As Chapters 3 and 4 illustrate, she became a director, but is finding difficulty in negotiating a meaningful role within the management team. Increasingly marginalised from the management of the business, this female founder has no share in the ownership. Ownership is reflected in the traditional structure of the family firm and is divided between three brothers, one of whom is her husband and ‘business partner’: ‘The ownership is divided between the three brothers. Obviously Tom has got 34 per cent which really works out at a third each. And then Tom’s father is the chair and he on the board of other companies, and is winding down a little and has no shares obviously.’ (Table 3.1, N37) This clearly demonstrates one way in which male kin benefit from the labour of female kin within systems of private ownership, for the ownership of the newly accumulated capital has bypassed the wife. This structure contains the strategy for the future development of the business. Each of the brothers has responsibility for particular geographical areas and it is anticipated that each will independently take ownership and control of their respective regions whilst simultaneously growing the business. The wife/partner does not question this arrangement and seems ambivalent about the issue of ownership. This is surprising given that she feels uncertain about her role in the business and indeed her marriage. 78 Class, Gender and the Family Business Another interesting permutation on the question of ownership is provided by a business (Table 3.1, N36) that consists of a number of companies including manufacturing, construction, property development and an overseas investment portfolio. The entrepreneur on behalf of the family strategically manages them, but on a routine basis the property development enterprise is managed by him, while his wife/partner manages the manufacturing plant. The idea is that each partner takes responsibility for a project, whilst in addition he takes overall responsibility, thus retaining control of the strategic management of the businesses. This man, like his historical counterparts, married into an affluent business family and was thus able to enhance his business portfolio. He appointed his wife as plant manager of the manufacturing enterprise and while he claims that she has complete autonomy over the organisation of this enterprise, he actively obstructed attempts to interview her. On the question of inheritance, although he has two daughters and a son, he takes it as a given that his son will inherit and manage ‘his wealth’. Typical of the portfolio entrepreneurs, this business owner believes in the fluidity of capital assets and is not committed to retaining any of his current enterprise, but is committed to staying in business, which means that his son is likely to inherit considerable assets in the future. Typically, although he argues that his wife’s business is a separately run concern, he does not envisage any challenge from her with regard to his decision on the question of the ‘disposal’ of ‘her’ business and the issue of inheritance. This indeed seems at odds with his wife’s natal family background, for she went through a type of male apprenticeship and was helped by her father into business prior to her marriage. Splits in husband and wife partnerships through divorce do not necessarily lead to the break-up of the business. In the ‘newly’ created business sector two of the couples divorced during the course of the research. What is significant is that in both cases the breakdown of the marriage did not immediately, as far as we know, affect the strategic direction of the business. In both cases the wives left the business partnership. What this suggests is that, ostensibly, divorce settlements do not destabilise core business interests. However, in both cases the partners had considerable wealthholding aside from their core business interests. In the first case, the concept clothing chain business (Table 3.1, N14), the husband continued in the business, and later sold his interests. He then used the investment to re-establish a previous and arguably less innovative enterprise in terms of the product, but secured a rather clever financial deal with a large supermarket which provided Gender and Wealth Preservation 79 a retail outlet for his clothing brand. The wife/partner moved on to an executive post with a major retail chain and as a result of the divorce settlement secured a smart house in a fashionable area in London. This entrepreneur brought one of his daughters from his first marriage into the business and she worked as one of his line managers. However, the baby son he had with his third wife he envisaged as the principal heir. Although the child was only a few months old the father had secured a place for him at a top public school in anticipation and in preparation for his future role. Couple N39 (Table 3.1) had businesses in the restaurant and hotel trade. The wife had considerable wealth independent of her husband, and as earlier chapters show, she had made a large financial investment in the hotel that she routinely managed. As a result of the divorce she abstained from the active management of the business and as part of the divorce settlement secured a large house in a fashionable area in London, while contemplating new business plans. Although the hotel business was subsequently sold, it is not clear whether this was a result of her calling in her investment. However, her withdrawal from the active management of the business undermined the whole concept behind the hotel, since the status of wife in this case gave meaning and identity to the business. This example may suggest that divorce and remarriage may alter the form of the business, but does not change the intentions and strategies for the conservation of wealth and lineage. The landed sector demonstrates that there is a similar process of wifely exclusion from wealth possession in the event of divorce. For instance, an entrepreneur inherited a small farm and, with his wife, built it up to a holding of 4,000 acres of arable farming, an engineering plant and property development. This business has remained profitable through the adoption of mass production methods in the farming of cash crops. Typically, the property development came as a result of land purchase and consists of the restoration of several derelict domestic and farm buildings which appreciated in value during the 1980s when rural living became desirable. Although he claimed that he worked in partnership with his ex-wife, this wealthholding is intact despite her departure from the business organisation and their subsequent divorce. He points out: ‘I divorced my wife. She lives in the family house in L. She settled for that and some money.’ In the few cases observed, this kind of settlement is typical of divorce outcomes. The wife lives in the family home, whilst he lives in another 80 Class, Gender and the Family Business of his properties in a different county. His wife no longer has any connection with the business and like earlier examples, ownership has bypassed her as a result of the manner in which the inheritance question has been resolved. He has already given two-thirds of the property to his two daughters: ‘We have divided the shares between the three of us. I have worked hard all my life trying to create something that will keep going. I don’t want the thing dissipating when I die and all sold. I don’t want the family getting hold of the cash and just spending it.’ Characteristically, his concern is that the business, or at least its product, the wealth, will survive after his death. With this in mind and not having a son he has introduced his daughters to the business and like other anticipant heirs they have experienced a form of apprentice training. Whilst not strictly adhering to the principle of primogeniture, he stresses the importance of business knowledge and points out: ‘I have always discussed business with my girls. When they were coming back from school we’d stop in at the “LC” and I would talk to them about the business. They were shareholders then. They would have to sign the accounts so, whilst they didn’t really understand them, I wanted to instil in them some business principles. For instance, that to borrow money costs money, and if you are going to borrow, then it has got to be repaid. I wanted them to understand that when something is yours, it can so easily be taken from you.’ To this end his eldest daughter, having completed a degree in architecture, has a career in the City with the aim of learning about investment and finance. She very obviously has been bestowed with the role of honorary male, for he considers that she also has the strength of character to strategically manage ‘his’ business. His second daughter works on the farm, but has had to develop her own enterprise in market gardening in order to prove worthy of her inheritance. The question of lineage also underpins the logic of this strategy, for he argues: ‘Because, long term, history tells us that land is re-cyclable on a very long cycle over thirty or forty years. So from my grandchildren’s point of view any land we buy now in thirty years’ time will prove to be a good investment.’ Gender and Wealth Preservation 81 This example demonstrates the clear links between capital accumulation and patriarchy sustained through lineage. These discussions also convey the sense in which future descendants are being provided for. Typically, such intentions and accompanying strategies bode inauspiciously for his wives who are peripheral considerations in matters of inheritance. He is married a second time, but his current wife takes no part in the enterprise. Again, this thinking has resonance with Pateman’s (1988) argument and the manner in which the person of the wife disappears behind the husband. The assumption here is that such wives will be taken care of. In the absence of sons this entrepreneur had prepared his daughters for ownership. Indeed, as Chapter 8 on independent women owners shows, in the relevant cases such women resort to convention, and despite marrying outside their lineage, transfer ownership to their sons. This finding is consonant with Thompson et al. (1976), who argue that, historically, in times of necessity the transference of wealth to daughters does not necessarily damage natal lineage. The question of lineage seems to have almost equal importance to the survival of the property for many of the male partners regardless of their class status. The next example involves a farmer who owns 600 acres of land and rents and farms a further 3,000 acres for the cultivation of commercial crops. He has recently reduced his business portfolio and has given his son responsibility for the management of the rented enterprise. The son is a working farmer and works on the land whilst he also manages the business. The benefits of this enterprise are that he is the beneficiary of the profits from the arable farm. The future plan is to buy this land, for land as a form of investment is regarded as more enduring and stable: ‘Any of the decisions that I have made have been with Richard in mind and with the view that he is going to take over. Well, there are still huge profits to be made in land, but it is not agricultural money. The money made is through inflation in land prices. It is just paper money. Land can only be invested in not for the return on capital but maybe with the hope of long-term growth, or the fact that it does not blow away in the same way as stocks and shares. You then see companies collapse which isn’t quite the same with land. People in industry see that. The tendency for those who have been successful in industry is that they will hive off money into land. It is seen as a good solid investment.’ Despite poor economic performance in the agricultural sector this farmer appreciates the longer-term value of land, which he wants to 82 Class, Gender and the Family Business acquire for his son. Passing on the rented farm and its subsequent purchase is the preamble to his succession. The son will eventually inherit the 600 acre farm, which has been diversified into an equine and leisure enterprise. However, reflecting earlier examples of wifely exclusion, this partial transfer of business interests to the son appears to have been precipitated by the divorce from the entrepreneur’s previous partner and first wife and his subsequent remarriage. He pointed out: ‘Originally it was the three of us. Before I divorced my first wife we were a partnership and then she transferred her share to Richard.’ This is a first-generation business and from a gender perspective suggests that wives in such businesses work in the business largely for the future benefit of their sons. On the other hand, it also seems that, according to the cases discussed, the circumstances in which second wives marry into first-generation family businesses with expectations of inheriting the core wealth seem unlikely. In the cases illustrated second wives marrying into such family enterprise are not part of the decisionmaking process with respect to inheritance, when it seems the clear intention behind inheritance is to pass on the core wealthholding from father to son. The ‘old’ business families reveal the same pattern and suggest that wifely exclusion is an aspect of the financial management of such business. This is how a 37-year-old heir to a brewing empire saw it: ‘Well, we don’t have a strict system of primogeniture within the family. But what we do try to do is to make sure that the shares go down one line in the majority of shares. I hold considerably more shares than my sister does (90 per cent). What we will try to do is to hand down those shares to one of the five children. My sister has three and I have got two. The first opportunity open will be for my son, but if that does not appear to be working out, then we will look at one of the others.’ (Table 3.2, O17) This discussion refers to the respondent’s own lineage, his children, his sister and her three children, members of the family connected through blood relations, suggesting that natal lineage is perhaps the only gateway to the family wealth. This is conveyed in the manner in which he fails to mention his wife, who is conspicuous by her absence. This business specialises in beers for market niches and has survived five generations of family management. He is both chair and chief executive of the business, taking full control of the family empire. Notably, Gender and Wealth Preservation 83 his wife does not own shares, while his sister’s involvement is as a minority shareholder. Typically, her role in the business is limited to attending the annual general meeting and acting as monitor to a family trust, while her primary responsibility would seem to be providing suitable substitute heirs. This evidence suggests that the marriage of the male heir does not endanger or lead to the dissipation of the core unit of wealth. The age of the business varies within this category and includes thirdgeneration ownership to landholding families that date back hundreds of years. According to the wives interviewed, with the exception of landholding, it is quite unusual for them to have secured a position in the business. In the case of the food manufacturing business, which is a third-generation enterprise, the organisational structure is consistent with the owner executive model (Goffee and Scase, 1985). Typical of the traditional family business there are several of the entrepreneur’s brothers employed in a variety of managerial roles in the company. The wife/partner is a sales director, and indeed this role is carried over into her domestic life. Yet, she still regards herself as an outsider in relation to the business. It is also noteworthy that she does not convey a sense of partnership, but rather sees herself as an employee. She is not included in the ownership, has no shareholding and cannot envisage this occurring. Her ambition is to resign from her post in the longer term and establish a career elsewhere. The interviews with these wives suggest that the dominant trend is for them not to get involved and generally they remain very peripheral to the management and ownership of such family wealth. Even in instances such as O10 (Table 3.2), where the wife is a shareholder, she assumes only a very tenuous sense of ownership of her husband’s core wealth, and this cuts across the industrial and landed sector, and ‘old’ and ‘new’ wealth. Typically, the wife of the heir to a medium-sized traditional engineering business in the ‘old’ business category said: ‘I don’t feel it is my place; again I’m not a member of my husband’s family. I’m probably too submissive on this, I don’t know how much I can say to you really. I feel he has given those [shares] to me, or because I have been given those shares it does not mean that I should have any say in the running of it. I trust them to do all that.’ (Table 3.2, O10) The respondent held a nominal 10 per cent stake in her husband’s toolmaking business, set up by his grandfather. In these instances a wife 84 Class, Gender and the Family Business is given shares for reasons of financial expediency, which does not encourage the possession of these assets. Her sense of ownership is purely passive and mediated through her husband. She sees herself as an ‘outsider’ without power or influence in business matters, and as such represents the traditional pattern. However, she has some personal wealth, which she inherited from her parents and this may be protected by a pre-nuptial agreement. The future survival of this particular business is uncertain, because the heir apparent, the eldest son, has a successful career in the City and sees little advantage in running an engineering business. The likelihood is that the business will be sold when the present owner retires. Despite these illustrative examples, which serve to highlight wives’ business roles, it is likely that wives’ efforts are not wholly accounted for because the men sometimes obstructed access and frequently underestimated the extent of wifely involvement. Moreover, given that, occasionally, during interview such entrepreneurs began to realise the extent of their wives’ efforts much wifely work may still remain hidden. This tendency is likely to continue, for the recent diversification of investment in such business can sometimes initiate types of enterprise that are stereotyped as being more appropriate for women, particularly in the landed sector, where there is greater unity between home and work. The irony here is that although such women are more likely to be involved in the business, their sense of ownership and access to their husband’s assets are perceived to be transient and remote. This view is concisely conveyed in the next example. Speaking of her relationship to her husband’s wealth one wife said: ‘I haven’t got anything. That’s his. It’s ours but not mine. Not really. While I’m around I can use it. I have the advantage of it, but I don’t own it.’ (Table 3.2, O08) This woman, from a rural working-class background, has married into the landed gentry. Her husband is heir to an estate, which has diminished to about 600 acres. Although still wealthy, the family is in decline but was in the past a large and politically powerful landowner in the area. His parents live close by in a modern residence and have vacated the country manor that overlooks their garden. This has been sold to and restored by a 1980s entrepreneur who both resents and emulates their class. Regarding the couple’s enterprise, there is a clear division of labour: the husband farms, while the wife/partner looks after the rental Gender and Wealth Preservation 85 properties. He is a working farmer and does most of the work. The wife’s role in the partnership involves the management of the properties that had earlier constituted part of the estate. This consists of a row of small properties which, in effect, comprise the village. The cottages had been used to house the farm hands and estate workers and are now kept as weekend homes and lifestyle dwellings. The wife/partner organises the improvement and maintenance of these properties. In addition, she selects new tenants and manages the collection of rents. Despite her involvement and interest in the management of the enterprise she makes no claim to ownership. Acting as custodian, she maintains and safeguards the property so that it can be transferred to their son. The tendency then is to safeguard core wealth, and this is again evident in cases where respondents are divorced. Three of those in the ‘old’ landed sector were divorced, and the following arrangement was considered to be fairly typical. S. was a particularly hardworking and successful entrepreneurial landowner, and produced cash crops for a well-known food manufacturer. The estate includes a very large house, part of which is run on a commercial basis to accommodate corporate entertainment. It also holds weddings and other social events. In addition, there is property on the estate, which was being turned into commercial enterprise. Other major assets include a collection of paintings, which, he argued, are all tied up in trusts. The estate is to be passed on to his son who has a career in economic journalism with a national newspaper. Thus the estate is left intact despite the fact that he is divorced from his wife who is a member of another local landed family. The divorce settlement includes a sum of money and some valuable paintings. She has returned to live in a property on her brother’s estate (Table 3.2, O05), a facility that is part of her inheritance from her natal family. However, the paintings are to go back to the original estate after her death as she had already bequeathed them to her eldest son who is heir-in-waiting. On discussing the issue of the potential power of female kin to break up the core wealth, one respondent, drawing on his own situation, said: ‘Well H. brought money into the marriage and in many ways it is all tied up.’ Interviewer: ‘Say, for example, you were to get divorced, could she not claim her share despite the fact that it may well endanger the survival of the estate?’ 86 Class, Gender and the Family Business Husband: ‘She certainly could, but I would expect that she wouldn’t want this either, and this would influence the settlement. And anyway it would not be in her interests.’ (Table 3.2, O05) These comments offer some tentative explanations which may suggest that such women, constrained by the practice of primogeniture and the legacy of coverture, behave according to their social class interests, even if this means that they remain ‘outsiders’ in their families of marriage. In this case, natal kin relations play a paternal role for in some exceptional cases, consistent with Erickson’s (1993) study, pre-nuptial contracts safeguard the personal wealth wives bring into the marriage. Wives thus appear to safeguard their own interests through their connections with their natal families. Some of the wives had considerable business interests prior to their marriages and have independent incomes, but there is some tentative evidence that these are often safeguarded by the terms of pre-nuptial agreements within such partnerships. For instance, the wife in the business partnership couple O03 (Table 3.2) is a member of an auctioneering family who manages her investment portfolio independent of her husband. Other prominent examples in the ‘new’ wealth category include the wife/partner in the hotel and restaurant business, (N39, Table 3.1) who has investments in the USA, and manages these independently of her husband. While the research suggests that wives often invest in their husbands’ businesses, there are cases where wives also have considerable wealth. When this is considered to be personal wealth it is not accessible for the benefit of the core business or for the husband/partner. The logic and function of personal wealth are that it challenges the whole notion of dependency, whilst it may also be a form of insurance against future hard times, as in the cases of divorce. Gendered socialisation practices that are embedded primarily in the culture of primogeniture account in part for the imbalances in patterns of wealthholding between female and male kin, and are a key cultural practice amongst business families. This means that children are prepared for different roles in the enterprise according to their gender and age. As Chapter 9 reveals, socialisation guarantees that male kin are perceived to be the inevitable and natural managers and leaders in both the industrial and landed sector, amongst the ‘new’ and ‘old’ wealth, and among majority and ethnic minority enterprises. Boys are encouraged to see themselves as heirs-apparent and this notion is fostered in the kind of education and training they receive prior to entering the business. Therefore, it is sons who are uniquely well prepared to take Gender and Wealth Preservation 87 on the role of chairmen and/or majority shareholders, and it is therefore not surprising that they later exclude their wives from the active management and ownership of the enterprise. However, as Chapter 8 suggests, where there are no sons, rather than jeopardise the survival of the property and lineage, girls receive a training similar to boys’, and are regarded as honorary males with regard to ownership. The importance of decision-making in choices concerning inheritance is that it is intricately tied into the survival of the business. On the one hand, heirs are not selected with great care, since the eldest son is given preference, and thereafter the assumption is that appropriate qualities suited to the job can be produced through socialisation. On the other hand, there is some recognition of the need to allow children to choose their own careers and for the prospective heirs to demonstrate that they ‘deserve’ their inheritance and are capable of taking it on. However, as Chapter 9 shows, once a son or, exceptionally, a daughter is chosen, their life-style and training are structured to lead to their responsibilities, which for the potential heir constitutes a type of ‘male’ apprenticeship. The wealthholders interviewed indicated that, with few exceptions, they would adhere to this practice in the future, and there is no reason to envisage any dramatic change in this pattern of ownership. As noted earlier, those who did intend to make their daughters their heirs are families without sons, a pattern consistent with historical studies. Daughters became heirs of the core productive wealth unit only as a last resort, a trend observed for all property-owning classes (Cooper, 1976; Thompson, 1976; Middleton, 1979; Erickson, 1993). Goody (1976) points out: Indeed, Yver sees the exclusion of endowed daughters from land as the dispensable means of keeping the patrimony in the lineage. The use of trusts are another important way to transfer and preserve wealth over generations. Over a third of the families interviewed use some form of trust to manage their wealth. A second pattern of entrusted wealth occurs when grandparents place money in a trust for the purpose of educating grandchildren. This type of trust is a very important resource, for it enables many of those interviewed to educate their children at top public schools. Even the use of such trusts is predisposed to favour boys. For instance, families insist in the most surprising of cases that boys want to attend public school, and it appears that there is far less pressure on girls to do so. For some families the 88 Class, Gender and the Family Business ‘finishing school’ is the distinctive mark of girls’ education, and, unlike their brothers who are trained to assume an active economic role in the business, they are groomed in social etiquette and wifely competence. Utilising trusts in this manner also preserves gender inequality within such families, whilst it sustains the family’s social and class position. In many ways these strategies convey the sense in which ‘new’ and ‘old’ businesses are managed, thus ensuring the preservation of family enterprise. The unequal inheritance patterns and unfair management practices are bound by an internal logic, that is, by a convention of cultural practices that are believed to the best way of preserving the business in the interests of the family. Conclusions This chapter has argued that wives in business partnerships with their husbands are bypassed when it comes to the strategic management of the enterprise and particularly when business wealth is transferred. This involves a set of cultural practices that shape the careers of family kin according to their gender identity. Primogeniture is a principal strand of this strategy and more or less guarantees a preference for the eldest son, who then takes control of the business at the expense of other kin members and particularly wives/partners. However, the logic of this strategy is that it safeguards the male lineage, the wealthholding and the class position of the business families concerned. 6 Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man This aim of this chapter is to interrogate the notion of the ‘self-made man’ and to show the connection between emotionality, domesticity, masculinities and enterprise. Contrary to Seidler’s (1989) argument, this chapter suggests that male emotion, particularly for entrepreneurial men, is not repressed in the public sphere, but is disguised in different forms and is expended in the pursuit of enterprise mirroring Victorian prescriptions of the capitalist ethic. In highlighting two typologies of entrepreneurial men, Ochberg’s (1987) notion of ‘men’s disengagement from the emotional’ arena is drawn on to show that entrepreneurial men free themselves for emotional expression in the business world. Men’s creative energy and emotional expression are additional resources that are consumed in the act of enterprise, and are contingent on men’s relationship to domesticity. At the same time, men retain their bonds in domesticity through the discourses of sacrifice and effort on behalf of the family, simultaneously elevating their economic role over other concerns. In describing the art of managing business as ‘emotional economy’, Roper’s (1994) work questions the exclusivity of rules as the sole source of managerial power. His colourful illustration of managers acting out their emotions and passions within the workplace signals that managerial power is rooted in more than a configuration of Weber’s bureaucracy. By focusing on relationships between men within the managerial hierarchy, Roper shows that emotion and sexuality are critical parts of the repertoire of resources that such men use in competition for positions of power within the hierarchy. While this is a laudable project, the easy manner in which he imagines that the structure of the heterosexual gender power relationship can be used as a heuristic device in explaining competition between male is problematic. This is because 89 90 Class, Gender and the Family Business the power relationship between male managers is very different from the power relationship between men and women, and particularly between husbands and wives in business partnerships. What is interesting about Roper’s work is that it provides a valuable insight into how such men, in mimicking the playfulness of heterosexual power, attempt to disguise male competitiveness. Whilst Roper asserts that management is an emotional game, Hearn’s (1993) concern is with the kinds of emotion that men use to retain their organisational dominance. The connecting thread between this argument and Ochberg’s (1987) views about men and intimacy, and Davidoff and Hall’s (1987) debate about the repression of male sexuality, is that from different perspectives they all point to emotion as a feature in men’s work. Roper suggests that postwar management men calculatedly limit the expenditure of emotion in domestic and wifely concerns, when such commitment to work is explained in organisational imperatives. Indeed, his joint interviews conducted with the managers and their wives convey only mild ambivalence amongst deferring wives. My own research suggests that wives and husbands both feel inhibited in the presence of each other, and that interviewing them separately may reveal differences in accounts. However, the men managers in Roper’s study, when talking about their careers, absentmindedly hint at the rancour caused by their lack of involvement with domestic concerns and the discomfort caused by rebellious wives. Scase and Goffee (1982) too are interested in the separation between home and work and on the impact this has on managerial careers and lifestyles. They found senior managers to be more involved with work, whilst men in middle management tiers, disappointed with the lack of career opportunity, disengage in part from the workplace and compensate through leisure, suggesting that, conventionally, men expect work to be emotionally involving. The naturalisation of male entrepreneurialism Although critical studies of managers are beginning to assert that emotion plays a major role in the managerial function, the literature addressing enterprise is characteristically premised on the superiority of rationality and particular kinds of human capital. It routinely speaks to a male audience and assumes that business is a distinctive male endeavour that involves particular types of men. Chell et al. (1991), Hebert and Link (1989) and Drucker (1985) typify an approach that stresses the connection between distinctive kinds of human capital and business activity. Typical of the more prosaic version of human capital theory is Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 91 Kennedy’s (1980) study of male business leaders, which suggests that entrepreneurial men can be distinguished by their management potential, long-term strategic orientations, ruthlessness, financial acumen, risk-taking and rationality. There are a number of problems with such an analysis. The first is that it elevates rationality and does not take account of power, or the importance of emotion in the act of managing. As this book reveals, emotionality is also critical to entrepreneurial men and they jealously reserve it as a resource to be consumed in business activity. However, this depends on men’s ability to access, allocate and direct the labour of female kin. Of course, emotion as a resource has a material context that is often the key to male business success. Male emotion as a resource to business is two sides of the same coin. On the one hand, male emotion is expressed as creativity, devotion, sacrifice and workaholism, but is disguised by rationality. On the other hand, it is absence from domesticity. Indeed, the euphemisms ‘family labour’ and the ‘family firm’ conceal the extent to which female kin, and particularly wives, are substitutes for lost male emotion work within domesticity. The reluctance to interrogate the notion of ‘family labour’ and the absence of women in entrepreneurial discourse reinforce the invisibility of women as a business resource in this context in addition to others. However, the different discourses on enterprise fosters the link between masculinity and rationality, whilst the absence of a gender analysis reinforces the myopia that exists in relation to male emotion work and enterprise. The point made is that male emotion resides in the public sphere and is increasingly there in competitive conditions, but is hidden. Whilst feminist literature has said very little about enterprising activity directly, it has questioned gendered assumptions in a wide variety of workplace analyses, as the following section shows. Entrepreneurialism and patriarchy Hearn’s (1992) notion of public patriarchy is a useful way of thinking about the manner in which male power historically shifted from the private sphere into all public sphere activities. The adaptability of patriarchy is continually demonstrated by the manner in which men have been able to maintain their dominance despite the changing material conditions characteristic of the capitalist relations of production. Indeed, the recent entry of women into important areas of political and economic life has had little demonstrable effect in changing the culture. As capitalist relations have expanded, the configuration of male power 92 Class, Gender and the Family Business has gained territorially from the narrow confines of the private sphere and the power of the father to the more diffuse yet pervasive power of men in the control of public sphere activity. However, at particular points, men make alliances with capital that serve mutual interests. Typically, as Chapters 3–5 reveal, although some business are established by wife/partners, and although they play a major role in the management of such enterprise, they are unable to establish an enterprising reputation. The lack of women’s reputation in enterprise simply confirms men’s well-established place as business leaders. Compared to women they are better placed to play the entrepreneurial game, for as Burt’s notion of structural holes and Boissevain’s notion of cultural capital suggest, men have created a playground of exclusive male clubs, where business links are forged and opportunities identified. Men are able to participate in cultural and social settings that encourages male allegiance and this is very important in enterprise. On the other hand, male allegiances are tainted by competitiveness, and this magnifies divisions amongst men. Theories of patriarchy that address the question of difference between men also suggest how such differences accommodate enterprise. Brod and Kaufman (1994) and Collinson and Hearn’s (1994) notions of masculinity denote a subtle move away from the repercussions of male power on women, to a more central focus on men and power, and men and masculinity, while still retaining a concern with men’s asymmetrical relationship to women. Their approach suggests that masculinities are a shifting constellation of diversity, difference and unity, anchored historically, culturally and materially. Enterprise provides an illustration of how such differences can become resources for some men. In this sense the act of enterprise enables business leaders to manipulate class/gender relations (Collinson, 1992), ethnic identities (Mac an Ghaill, 1994) and sexuality (Mac an Ghaill, 1993). Additionally, fitness, age, emotional labour and distance from domesticity influence how men compete with or make alignments with each other in the process of creating a business. As the following discussion will reveal, such entrepreneurial men emphasise co-class/ethnic identities to access reservoirs of labour, while notions of fitness and ‘cold’ rationality help them to distinguish themselves from other, ‘lesser’ men in the making of masculinities. At the same time, male emotionality, in the guise of passion, drive, enthusiasm, sacrifice and workaholism, serves the logic of enterprising rationality amongst striving men. In this chapter I draw on the life histories of first-generation entrepreneurs and their families. These cases are typical of particular types Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 93 of entrepreneurial masculinity, although the men in question began their businesses in very different economic conditions. The aim is to explore what kind of entrepreneurial men they are becoming (Kerfoot and Knights, 1996) and whether, and in what ways, they differ in their approach to wealth creation. The first model is embodied in the notion of ‘the company man’ and comprises a belief in internal growth and a risk-averse approach to financial management, while technical expertise and pride in the product and company take priority over short-term profitability. The second model, embraced in the notion of ‘the takeover man’, is very different because it is moulded by quick profits achieved through financial manipulation, where growth is facilitated by takeover. What distinguishes types is the approach and form of accumulation. For instance, the ‘company man’ embodies an identity and commitment in the idea of a recognisable product, something stable, secure and established. By contrast ‘the takeover man’ is single-minded about making money and promiscuous in the manner he enters different sectors, with no commitment to creating a product, but rather with a destructive urge to extract profit. The men in the following study came from workingclass backgrounds and had made good. In this sense I want to highlight their similarities and differences and how these embody a strategy, or strategies, for success in business. Are their shared backgrounds important in the construction of their masculinities? Do their different nationalities, education and age impinge upon the kind of men they become, and how does this influence their approach to business? How are masculinities shaped by specific material conditions such as migration, work activities, male working-class discourses and domesticity? Has difference between entrepreneurial men any relevance for the politics of domesticity? The company man Aged 76, Mr M. was still active as chairman of a multi-million-pound, privately owned and run, civil engineering business he founded in 1952. His vision of successful enterprise is in building up a business identified by the product and service it provides, something substantial which can be transferred to his children. His eldest son is managing director, his daughter is a director and a younger son is training for a senior position. His manhood and patriarchal identity are all bound up in the original business and its ethos, for its activities are still in the characteristically Irish sector of heavy plant machinery, lately diversifying into construction, open cast mining and speculation in industrial 94 Class, Gender and the Family Business land. Such diversification is not merely opportunistic, but a rather gradual development of the founding venture. In some ways Mr M. conforms to the model of the ‘self-made’, self-educated, ‘hands-on’ practical man of the postwar industrial sector, whose prior commitment is to product development as opposed to quick profits (see also Roper, 1994). There is a sense in which he couches his achievement in a language which conspires to the ideology of the self-made man. One of the most striking features about interviewing rich and successful men and women is the sense of power and confidence they convey. This, of course, is stage-managed in the ambience of a plush office and similarly grand domestic settings. By contrast, the office suites of Mr M. and members of his family are fairly modest. Discreet about his private wealth, this setting is very much tied to the image he wishes to convey. Although he is chairman, he wants to be recognised as a ‘working man’, someone who earns a living through hard work. Work and ‘his’ business remain the centre of his life, and he exudes an unrelenting energy and enthusiasm in telling the story of the company success – his success, based exclusively on his efforts. He relives the key moments of the business formation, filling out the contours of each stage with impressive detail, remembering others’ help only when prompted. With regard to his wife’s participation, there is an emphasis on a rigid division of labour and a denial of any contribution on her part to the business. Sennett and Cobb (1977) draw attention to the double-edged notion of toughness and the meanings it has for working-class migrant men. In debating class as ‘injury’, these authors challenge notions of machismo and show them to be ideologies that conceal personal pain, the denial of weakness, while serving to legitimise conditions of exploitation. This is consistent with Hearn (1992), who makes a connection with forms of alienation and particular masculine behaviour. Toughness embodies a belief in the power of the body and equally importantly in the strength of the mind. However, it is strength of mind that separates such men from their peers. Typically, toughness is the touchstone of Mr M.’s vision of masculinity, an image which may be at odds with this small, slim man, conventionally but immaculately dressed in a pin-striped suit. But the stress on physical toughness is partly linked to his earlier occupation and lifestyle. Beginning his career at the age of 17, when his father died, he migrated from Ireland to Britain. As the eldest of eleven children he saw few prospects on the family’s small farm. Assuming the role of breadwinner for his mother and ten dependent siblings, he worked initially Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 95 as a farm labourer. Constrained by his lack of formal education and Irish migrant background, he, like many other Irishmen over the next twenty years, worked in the construction industry in a variety of manual jobs, moving to a different location with each new job. This job market has long been the ghetto for rural male Irish labour. Indeed there is a dynamic relationship between the characteristics of this kind of occupation and the rootlessness, isolation, alienation and the ‘macho’ culture that it nurtures. Although the image of the Irish construction worker as a drunken, brawling and tough ‘navvy’ conforms to a racialised stereotype, like other stereotypes, it has some validity. The reality is that such work requires physical stamina, and men, finding themselves in these circumstances, are forced to act out ‘macho’ behaviour and do internalise some of its values. But this can be explained by the alienation associated with migration and the conditions in which these men were forced to labour, and very often the poor domestic conditions they endured. This arduous work experience calls for physical strength and is a necessary socialising ritual in the construction of a particular masculinity. It is the rite of passage to this particular male club. Social rootlessness fosters a camaraderie between men in which displays of muscle power, personal spending and drinking are seen as virtues, which suggest a lack of control, but may be a compensation for the absence of family and wives. The whole emphasis on the power of the body and the experience of social rootlessness generates the need for self-reliance and independence from these constraining and destructive circumstances. However, such men argue that the transformation of their class position is contingent on ‘keeping your head’ and staying in control through strength of mind. Notions of sacrifice and endurance are intertwined with economic duty and paternal responsibility. Ideas about independence and breadwinning form dynamic themes in this version of manhood, for the boy acquired a man’s responsibilities, a factor not unconnected with the theme of thrift. With his starting pay of £l 17s 6d in 1932, and after a stretch of twenty years’ work, he explains: ‘I had fourteen hundred pounds in the bank. I’d saved that. I’d earned good money during the war.’ This challenges the racial stereotyping of Irish Catholicism, and conforms to Weber’s model of the Protestant ethic of hard work, thrift and the Victorian habit of rationalising the self through discipline. During this time, Mr M. gained an insight into business and acquired some technical and managerial skills. He learned to drive and maintain plant and machinery, and had worked as foreman for a number of years in his friend’s contracting company. This was a 96 Class, Gender and the Family Business key moment in his life, for he got married and simultaneously resigned from his job and became self-employed. Spending £200 of his savings, he invested in his first piece of machinery, a second-hand tractor. This event is clearly linked to financial independence and is an acknowledgement of the dependence of others on him. Increasingly he became a workaholic and made £8,000 profit in the first year: ‘I went out on my own driving the machine, getting the jobs and doing them. I “broke” that machine. I worked seven days a week, sometimes fourteen hours a day. I was always going down the garden path by 6.30 am. That’s how I did it.’ (Table 3.1, N32) The emphasis is on successful profit-making, whilst the premium is on individual effort, this time measured in physical power that not only controls but also defeats the durability of inanimate objects, thus conveying the superiority of human mastery over machinery, for, he explains, he ‘broke the machine’. In other words, he worked the machine to its destruction, and beating it, he relishes its demise. The central issue here is the power of the body over the machine, another manifestation of the theme of physical toughness. The ideology of masculinity both masks the limits of this particular masculinity and its class basis, and also underplays his other possible skills. It is partly an accommodation to the racial stereotype of Irish male labour, where ‘unskilled’ labour alternatively relied on the power of the body, yet it is also a way of living with the indignity of a poor education, although clearly he had by this time acquired sophisticated managerial and business skills. Willis (1977) observes a similar vision of toughness among working-class men. During the interview the sense of indignity fostered by his poor education was continually replayed in self-mockery. In recalling this painful biography, Mr M. also wants to convey his strength of character and the power to transcend the indignities of such constraints. Like the men in Sennett and Cobb’s (1977) study, Mr M.’s apparent ambivalence about the merits of formal education may cloak the pain he has endured. Paradoxically, during his earlier career he learned several skills essential to becoming self-employed – how to cost jobs and rudimentary accounting. Describing these coping strategies also allows him to demonstrate his intelligence: ‘And I used to have my balance sheet in my pocket. When I looked at a job in those days I’d have to estimate how much I’d get for doing it. Against Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 97 that I’d have to calculate my wages and the fuel, whether I’d be able to do the job, and how long it would take. I had no degree or anything, but I rarely made a mistake. Nowadays they have degrees and they’d be there measuring up and so. They still don’t get it right. And me, I could tell by looking.’ (Table 3.1, N32) His denigration of formally skilled engineers has parallels with the workers in Collinson’s (1992) study, who knew that formal education was one possible route out of one’s class, but to admit to this is to devalue one’s version of manhood. At the same time, formal education acts in opposition to working-class masculinities, for in one sense it feminises ‘real’ men (Sennett and Cobb, 1977; Collinson, 1992; Roper, 1994). These contradictions are again reflected in Mr M.’s approach to his children’s education: ‘Well they all went to university and got their degrees. Michael got his in civil engineering, but all of them, including Pauline, had to go on site and work. And I insisted, much to his mother’s disgust, that he did the hardest jobs for my most cantankerous foremen. Michael had to prove himself, learning to drive every machine and by being willing to do any job. And I mean Pauline did jobs in the yard. Their mother thought that they shouldn’t get their hands dirty. But you see they did that and got their degrees.’ (Table 3.1, N32) The rite of passage to supposedly authentic masculinity is the test to survive the demands of manual labour. His children, including his daughter, proved they were ‘real’ men. The logic of this is that it is a preparation for possible future ‘hard times’, whilst acting as a warning against profligacy in the face of future temptation. At the same time, by insisting on manual labour and formal education for his children, Mr M. has upheld the value of his version of masculinity whilst also transferring and fulfilling his wish that his children be well educated. To admit or to dwell upon the limitation of his own poor education would be to highlight the limits of his power and masculinity. This went against the grain of ‘getting ahead’ and setting himself apart from his peers and rivals: ‘There was a big job out at Company X. There were many problems with it. The experts saw it and wouldn’t touch it. And I suppose if I had seen the dangers I wouldn’t, but I hadn’t. But as I went along doing the job, I 98 Class, Gender and the Family Business got better and better. They [colleagues and friends] all said, “It will be the last of him, it’ll kill P.” But that is where I made the money – on the jobs that other contractors wouldn’t want.’ (Table 3.1, N32) This sense of independence and the need to distinguish oneself from other men underline his comments, and are consistent with aspects of the rugged individualism espoused in conventional entrepreneurial theories discussed earlier, such as risk-taking. Whilst physical endurance and technical superiority are some of the hallmarks in his version of successful entrepreneurial masculinity, they are also part of workingclass ideologies and discourses. Essentially for men like Mr M., the emphasis on toughness of the body and mind became the means by which to transcend the alienating conditions associated with one’s class. In class terms ideas about toughness are very important in the construction of mechanisms that both create and safeguard business. In the case of Mr M., arguably toughness encourages self-sacrifice where ‘real men’ have the strength of mind to endure such trials. The idea of the ‘strength of mind’ has other parallels and is tied to ‘hard masculinity’ when affluent men of other classes are trained to resist the temptations of profligacy associated with affluence and privilege. As the notion of ‘apprenticeship’ (Mulholland, 1997), shows, this is acutely evident in the tough public school system that initiates the early separation of children from their parents and is a part of character-building that features in the preparation for the responsibilities of inheritance. This brand of individualism stands juxtaposed to the family, class and ethnic solidarities which had been so central to Mr M.’s survival. Sustaining these loyalties is also limiting, and attempts to transcend such limits invite some risks: ‘I had been with the G. [a very large private company] since 1948, and they were my friends. But I had done a lot for them, worked hard all hours of the day and night. In 1952 we had a big difference and I jacked the job in [resigned]. And my four years of high class college [ironically] with the S.s. I had done everything with them, I knew all my plant, machinery, the maintenance, and above all, I could do evaluations. Anyway, what I really wanted was to do something on my own.’ (Table 3.1, N32) This comment reveals several tensions. On the one hand, it resonates with a strong emphasis on independence, as an integral part of certain forms of working-class masculinity. On the other hand, the conditions of becoming an entrepreneur involve the interplay of class, ethnicity Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 99 and working-class masculinity. At one level, moving into selfemployment entails disloyalty to one’s group, when identities and loyalties are subordinated to the needs of capital. In this case the respondent set up in competition with his former employer, gaining direct access to markets. At a second level this reveals the contradictory character of masculine solidarity, when friendships between men are challenged by the capitalist impulse. At a third level, unravelling the racialised stereotype of their rational and untamed ‘Irish navvy’ revealed a regular saver, a cautious investor, a disciplined worker and an astute businessman. Setting oneself apart through transforming one’s class position creates another set of tensions between class and ethnic solidarity. A discrete notion of ethnicity may gloss over class contradictions (see Ram, 1994, who is reluctant to notice this) and partly conceals the tensions and conflicts, the capitalist essence of the wage-labour relationship. Instead of being a worker employed under the conditions of ‘lump labour’1 drawing on his own ethnic group, he became an employer of such labour. Together with a climate of economic growth characteristic of the 1950s and 1960s and astute financial management, there were the essential elements in his model of entrepreneurial achievement. In this sense aspiring working-class ethnic masculinity reflects and reinforces middle-class entrepreneurial competitive values. The same lack of sentiment and rationalising is adopted in relation to the employment of his brothers in the business: ‘When it came to the business, there was no favouritism, and even now this applies to my children. They have earned their places. Now I had several brothers, two were great men and became directors, but some of the others, well – some swept the yard. What divides us is “keeping your head”. I mean one went on the bottle and killed himself. And I can tell you so many hard men end in the sewer down and out. Then there are others – and they become gangsters – look at some of the Irish in America. Others never pay their taxes. I have always operated by the book, clean. That’s why I have a good solid business. We are known for our reliability and service – that’s better than dirty money.’ (Table 3.1, N32) The process of setting oneself apart can be physical/geographical or social/psychological, which means rejecting some of the destructive values associated with masculinity and community. It entails personal self-denial and refusing the camaraderie of hard drinking and the seduction of making easy money. Mr M.’s honesty and hard work separate him from his fellow countrymen and some male kin, and justify his 100 Class, Gender and the Family Business business achievements. At the same time, this shows how the suppression of sentiment and emotion is consistent with ‘rational’ decisionmaking and control – the prerequisites of managerial professionalism (Hearn, 1987). Financial acumen ran parallel with profitable capitalist activity and continued to be the hallmark of Mr M.’s business progress, themes that strongly feature in images of middle-class entrepreneurial success. For instance, selling and re-buying his company is the nadir of his career. He sold 65 per cent of his company in 1965. Having negotiated a very good price he used the money to buy a 500-acre estate in Ireland with the intention of farming. However, during the following seven years he became unhappy with the manner in which the company was managed and organised a meeting with his partner, intending to sell his remaining 35 per cent of the company, which was under-performing. The meeting resulted in him buying back his company. Mr M. recalls the high points of his financial wizardry: ‘They offered us a poor price, so we decided we’d try and buy back our 65 per cent at the price offered to us for the 35 per cent. They finally agreed. Of course I had to sell my estate, but within six months I’d paid for my company, and then started it as a family company.’ (Table 3.1, N32) Once the initial wealth is established, the emphasis shifts from muscle power to the financial wit of the entrepreneur in the art of boardroom negotiation. The process of creating a business and accumulating visible structures of wealth is also a sign of intra-generational class mobility, and to admit ignorance of such significant matters as finance at this stage would be to point to a chink in the armour of the invincible selfmade entrepreneur. In the case of Mr M., aside from recruiting professionally trained financial advisers in the administration of his business, he learned accounting and acquainted himself with the broader issues relating to business. Attempting to emulate his perception of middleclass behaviour, he regularly reads the Financial Times and economic periodicals. For him, a sound business is independent of the shackles of borrowing, and Mr M. gave a detailed account of how his bigger ventures were financed. The masculine discourse surrounding the triumph of financial wheeling and dealing often belies caution, but it engenders the feel for power. It makes men feel powerful, and it is the guile of power which they find so seductive. Indeed this is not unconnected to workaholism: Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 101 ‘I don’t take holidays, or days off. My leisure is the occasional meal in a hotel, and a rest on Sunday afternoon. Mind you, later I go out to survey some sites, my work is my pleasure.’ (Table 3.1, N30) In this case the proprietor of a multi-million-pound business in speculative house-building, motorcycle manufacturing and estate farming typifies the cult of workaholism. The emphasis such enterprising men place on workaholism has an additional explanation anchored in both the public and private spheres, and is contingent upon the question of emotional labour. The discourses of self-denial, sacrifice and punishing work schedules may well be rooted in the market. In other words, the competitiveness in such markets calls for extraordinary effort endorsed by the ideologies of the breadwinning role. But for such men work is the site for emotional expression and rejuvenation. Work is without a doubt their first love. The experience of building a business, the ‘lows’ and ‘highs’, are seductive and part of the creative process, which is felt intensely and personally. The wife and ex-working director of a very successful hygiene firm explained why she opted out of active management: ‘Well, I’d done all these things, but the business was his idea, his baby, he lives for it.’ (Table 3.1, N7) Roper (1994) captures this sense and meaning when he draws an analogy between entrepreneurial success and giving birth. Workaholism also endorses masculine independence and strongly upholds the male breadwinner’s role, thus sustaining the very mechanisms that reconstitute male dominance. Mr M.’s success, power and wealth are reflected in a lifestyle of tasteful affluence. He lives with his wife in a period manor house, complete with swimming pool, fitness and games rooms. Adjoining cottages provide separate accommodation for one of his six children. He has an interest in art and has bought some minor paintings, has owned a yacht in the Mediterranean, a 500-acre estate, likes horses and regularly attends Ascot – interests and consumption patterns consistent with the upper middle classes. This particular vision of entrepreneurial masculinity has been founded upon changing class identities, ideologies and discourses. The contradictory character of a masculine identity is founded upon the notion of manual labour. It both elevates and denigrates working-class masculinity. However, this cloak for class and self-exploitation, spurred 102 Class, Gender and the Family Business on by gain through favourable economic conditions and a belief in competitive values, driven by the seduction of power, has the capacity to transform and reconstitute working-class manhood in the realm of middle-class enterprise. These combinations of entrepreneurial masculine identity are embodied by the manly act of creating a business, something durable, solid, useful and productive. Equally, this masculinity has a hidden dimension: absence from family duties and the control and rationalisation of the self. Male emotion has been consumed in the construction of the business and in the making of money, powerful embellishments to masculinity. Yet, for all this, while Mr M. can, in material terms, be objectively categorised as belonging to the property-owning class at heart, subjectively he is a man among men only in relation to his earlier ethnic identity and class. The takeover man The resurrection of neoliberal economics promoting the virtues of the free market underlines the discourses and ideologies of recent popular managerial literature. When translated into notions of enterprise these advocate rugged individualism and the power of human capital and are presented as a panacea for the negative effect of the economic restructuring characteristic of the 1980s. New breeds of entrepreneurs have emerged who espouse these principles. Aged 38, Mr A. belongs to the new generation of opportunistic, profit-oriented free marketeers. Paradoxically, his business ethos is founded in the aftermath of dramatic structural change, the shift from public to private ownership, the shedding and the casualisation of labour and the legacy of boom-and-bust fostered by credit. When translated into notions of entrepreneurialism these advocate rugged individualism and the power of human capital and are presented as a panacea for the negative effects of the economic restructuring characteristic of the 1980s economy. His prime business interests stem from company failure and the casualisation of labour markets, hallmarks of the l980s economy. He is chairman with a 10 per cent share in a public company of which he is the founder, with a £40 million annual turnover, specialising in contract labour, employment services and in the rescue of small and medium-sized private businesses threatened with liquidation. Additionally, he runs three private companies in London. Conducted in his home, this interview was intended to explore his lifestyle, patterns of consumption, class aspirations and sense of Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 103 achievement, all of which embody a very different entrepreneurial masculinity in the making. This is indeed class-bound, for his most cherished personal possession is a recently acquired manor house in a Midlands county, for which he paid £1 million. Since he purchased the house he has spent £200,000 in restoring it to its original style. This is not the tasteless grandeur of the nouveaux riches, for that would betray his class background. A life-size portrait of his wife hangs above the huge mantelpiece, and the image conveyed is that of a country squire with an upper-class background. This sense of class and social status is very much endorsed by the fact that he lives in the ‘big house’ overlooking a small village of approximately ten cottages in which the previous patrician owners and their tenants now live. Highly critical of privilege, he described the patrician family as ‘wastrels’, who had allowed the house to deteriorate and a 13,000-acre estate to be frittered away in financial profligacy. He clearly felt that despite his underprivileged background his talents and hard work had triumphed over the privileges associated with breeding and class. The former lady of the manor held him in equal contempt. In an earlier interview she suggested that the sources of his wealth and nature of his business remained an unfathomable mystery. But all of these threads are constituting embellishments to an image of traditional upper-class masculinity to which he aspired. Beautifully dressed in expensive and perfectly matched tweeds, he displays impeccable manners which are intended to complement the image of the country gentleman, a standard of dress that such men did not match. The location of this interview also conveys the idea of a leisured lifestyle associated with the moneyed classes, while also portraying him as a family man. This is both in the traditional sense as a family patriarch and head of the family, and the ‘new man’ who happily participates in child care and family life. As Davidoff and Hall (1987) and Veblen (1949) have argued, the family is part of the build-up of the successful capitalist, which also endorses paternalism, part of the construction of a specific and aspiring middle-class masculinity. In contrast to Mr M., who portrays himself as a workaholic, Mr A. draws on ‘soft’ masculine images that are woven around the ‘new man’ who takes an interest in domesticity with the seeming effortless grace of the traditional patriarch. At the same time, this seems to be intended to convey a sense of relaxed elegance, which in turn gives the sense of a man in control. Marriage and having a family form the crucial rite of passage to this particular masculinity. Family and leisure are used to convey a sense of wealth and status. In fact, Mr A. has three children, one of 104 Class, Gender and the Family Business whom lives with his first wife, while Mr M. has six children and is surrounded by them. However, Mr A.’s class background belies this image. He was born in south London to working class-parents who were ‘. . . very, very working-class, and very left-wing. My father worked for a London Council on the manual side. My mother was a Geordie, and there were five kids. She was brought up washing floors, and she was still cleaning when I was fifteen, or sixteen.’ (Table 3.1, N37) Whilst for Mr M. association with one’s class of birth and ethnicity proved to be a springboard to enterprise, Mr A.’s strategy is to distance himself from his roots, his class and his family. The sense of distance is strongly conveyed in the significance he gives to the house, which he explained was ‘the roots and heart’ of his family. Psychologically and geographically he left his natal family when a new identity was being formed, assisted by education. This helped him to acquire social skills, grace and sense of relaxed superiority, self-confidence and being in control, attributes long associated with the upper class. As he explained: ‘I got an exceptionally good education because I was fairly musical, so I got several musical scholarships and various bits and pieces. I did a season on tour with the orchestra. I had various other opportunities in that line. So that got me a better education than I would have had otherwise. And it got me away from home, which was a good thing.’ (Table 3.1, N37) By leaving home, socialisation within a working-class culture was avoided and a middle-class value system and speech codes were acquired, skills essential to upward mobility. Yet having acquired this demeanour, Mr A. still endures the pain of his poor background. It is not that men like Mr A. are ashamed of their background; rather, they fear the repercussions and degradation of the harshness of working-class life. This theme forms a continuous strand in Mr A.’s career and personal development. For instance, in the early 1970s he read politics and economics at a London university, a route to upward mobility. Untypically perhaps, he did not enjoy student life or the political atmosphere there, preferring to abandon his degree to embark on a career in catering. Starting and soon tiring of work as a ‘redcoat’ at Butlin’s, he went to work in a Paris hotel. In many ways this move can be accounted for by his class back- Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 105 ground and working-class values. Some working people see little benefit in attending university and reading something as esoteric as economics and politics. Of course, very often there is a real need to earn money. However, Mr A. had a specific goal, which was to save money to buy a hotel. Using his savings of £5,000, he entered the property market, buying two houses in need of refurbishment. He then got a job as an interviewer with an employment agency, while his leisure time was spent restoring his property. These houses were later sold at a substantial profit. The cultivated image of leisurely affluence betrays the strategies involving thrift and the celebration of the work ethic. Most young people would at least relish the experience of three years of student life. But Mr A. left and this reveals a working-class masculine ambivalence to studying, partly conforming to another version of the cult of toughness so strongly exhibited in Mr M.’s account. There is a sense in which this is not the real work of a man. This thrusting young man preferred the sense of purpose manifested in the frantic activity, risk and insecurity of moving between low-paid jobs and the early penny-pinching. Unable to cast aside his working-class upbringing he had by this stage married and had a child. These critical points in his early life acted as part of the rite of passage to manhood and a very contradictory masculinity. Driven by an acquisitive, highly individual ethos, Mr A. explains that in the early l980s he ‘. . . canvassed a job with a London company. I went in there as a site negotiator, finding new sites for them. And they were turning over £200,000 and I found that I was fairly good at negotiating. After three years of doing that I was made managing director of the company. I took the turnover to several million, of which £2 million was just profit. They wouldn’t give me any equity, I was a paid managing director, I was paid very well.’ (Table 3.1, N37) The need for independence is a feature of male working-class values, but the means of achieving this through managerial enterprise is more consistent with middle-class values and perceptions of money. Accumulating wealth is one aspect of a parallel process, while men gain control over money, they also enhance their masculinity. The power over money is what distinguishes them from other men in other classes and lesser men in their own class. However, such drive and competitiveness is only achieved even by their standards at a price: 106 Class, Gender and the Family Business ‘If someone were to ask me “What is it that makes anyone successful?” I’d say three words, fear, greed and creativity, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong in that. Well, with fear I’d put insecurity until you reach a level of wealth where you decide, “Well, hang on a minute, what is it all for?” People are afraid of failure, the insecurity breeds a fear, a fear that you are not quite as good, or you should he better. With that fear you have got loneliness. It’s a sense of urgency.’ (Table 3.1, N37) Unlike the ‘macho’, invincible mask presented by Mr M., this respondent admits to self-doubt and human frailty, which is consistent with the ideologies of the ‘new man’. He talks about his vulnerabilities, motivations and fears. This comment exemplifies some of the contradictions associated with masculinity and entrepreneurial activity. Pursuing the capitalist impulse creates a sense of loneliness, alienation and a lack of solidarity and intimacy (Sennett and Cobb, 1977; Fromm, 1978; Brod and Kaufman, 1994). Unlike Mr M., who appears to have found the process of building a business and creating wealth emotionally satisfying and fulfilling, Mr A. continues to feel insecure despite his wealth. This difference may be partly explained by the difference in goals between the two men: Mr M. wants to embody his self in a tangible business, while Mr A.’s energy evaporates in the manipulation of financial deals. Sherrod (1987) suggests that friendships between men, and the relationships between men and women, are transformed by the nature of work, noting that capitalism fosters competitiveness between men, which compromises their friendships with other men. Consequently, men transfer their emotional needs to women, whilst refusing to reciprocate affection. This has some resonance in the manner in which Mr A. evaluates his personal life against his entrepreneurial achievements: ‘Well, you see, within two years I’d made £12,000, and I was made MD in that company, but I’d ruined a marriage. You get inside and you feel – I was married at nineteen. You grow together or you grow apart. It is a question of whether your personality and interests take a parallel course. If you go through a few outside wars together, you grow together. It was not the pressure of work, because I didn’t feel that I was working very hard. Well, you see, it didn’t seem at all like work. You see it was the fact that I came home on quite a lot of occasions and I realised that we couldn’t actually talk to each other. Yep, it was a very hard decision, because there was a child involved. That dragged on, but it was an uncomfortable period, Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 107 and you have to make decisions and do things that are correct. As I say, you grow together or you grow apart.’ Interviewer: ‘Did all that affect your business?’ ‘Not at all, not in the slightest, there was an enormous amount of luck involved at that stage. It was the height of the eighties boom.’ (Table 3.1, N37) On the one hand, individualism, single-mindedness, instrumentalism, the basis tenets of the acquisitive enterprise culture, rationalised the tensions between the obsessive pursuit of material gain and personal loss. On the other, and resonant of Ochberg’s (1987) argument, this comment again emphasises the inseparability of home and work, and the manner in which men are able to channel the direction and consumption of their emotional energy. While this comment stands in stark contrast to his attitude and practice to his current family, it also demonstrates the way in which market-based activities mediate and shape the construction of a certain kind of entrepreneurial masculinity. A wife and family were not so essential to an aspiring businessman, but are considered very necessary to a rich and leisured aspiring ‘gentleman’. Talking about his failed marriage, Mr A. appears more open about the repercussions of workaholism than the earlier respondent, but in a way it is retold in the same tone one might use when recalling a moment of business failure. Ochberg (1987) embraces the essence of such rationalising when he argues that men have internalised a personal demeanour rooted in their external and public role. In this sense, one suspects that Mr A. does not address the real reasons for his marriage breakdown. He suggests that it resulted from a difference in personalities and an inability to grow together. But growing together would have been difficult because of his absence from home and obsession with work. Yet responsibility for the breakdown of the relationship is transferred to the partner, who apparently was unable to adapt to the changing situation. Instead of dealing with this loss, his emotions and energies have been harnessed to the momentum of the casino economy which leaves little time for life review or self-reflection. Emotions are consumed in the ‘buzz’ of profit pursuit. There is no recognition that work has become an obsession. The separation of home and work masks the repercussions on men’s personal lives but it is upon this façade that masculinities rest and thrive. Personal loss did not stand in the way of the pursuit of money, for he soon set up an advertising business. 108 Class, Gender and the Family Business On the one hand, themes of instrumentality and quick return inform his approach to business. Opportunism remains the underlying ethos, for by 1987 he had merged the company with another business, floating it to a £7 million capitalistion on the stock market before selling it. Unlike Mr M., whose personal constructions of masculinity were built over time around a particular unit of capital, rooted in a specific activity, this respondent’s activities are transient, ephemeral and difficult to quantify. On the other hand, it is an activity which he distrusts, for it is tinged with anxiety and uncertainty. There is almost a sense of disrespect for the process and this is manifested in low commitment to sustaining capital in any one activity. As he explained: ‘My motto is: to buy, float and sell.’ Mr A. has now started another business in asset stripping. The rapid expansion of his business empire began in 1989 with the accelerated collapse of small businesses. Since then he has bought ten companies, which had been firmly established but were undergoing some difficulty. Benefiting from the failure of others, he draws on bodily metaphors to describe the strategies in rationalising such businesses, for instance ‘picking off the heart of a business’ means retaining its profitable elements. The theme of financial machismo characteristic of a harder masculinity intertwines with a ‘softer’ masculinity more associated with the ‘new man’. These contradictions are played out in individualism and selfinterest in the pursuit of a quick return, which are the hallmarks of his business style. Yet the emphasis on his immediate family and the manner in which he exudes a sense of loss suggests a sensitivity which he continually strives to control. Driven by fear of poverty he seeks to transcend his natal working-class background and adopts a highly detached relationship to business activities. Unlike Mr M., he does not identify with a specific product or indeed with any capitalist competitor. He does not conform to Penrose’s (1980) model of the business manager for he is not interested in the notion of company expansion. His capital is kept liquid, accommodating and celebrating opportunism, which perhaps typifies the unregulated marketeer. He is more interested in accumulation. This model ties in very well with the point made earlier, his identity, unlike that of Mr M., is less embodied in the business and more in the idea of the family, which is symbolised by the grand house. Arguably, since identities are socially constructed in the public and private spheres and therefore transient, building an identity around the family and conveying a sense of 1ifestyle seems all the more important. Most entrepreneurial men see virtue in sustaining punishing work schedules, suggesting that their established businesses embody their Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man 109 earlier struggles. But Mr A. wants to convey something quite different – not the solid unit of productive capital sustained over time, but a lifestyle stemming from the private sphere which resonates with consumerism, a grand house and latest cars, and where the source of wealth is remote, apparently unconnected and appears very detached from his working-class roots. Even Mr A.’s second wife complemented his brand of success. As he explained: ‘No, my wife does not have a career now. I can afford her not to have one. Except, of course, she has a very important career as my wife and mother of my children. She is a wonderful, talented, intellectual woman. She is a graduate with a degree in Slavonic studies and speaks several European languages, including Russian. She, of course, has interests, she is secretary of the local English Speaking Society, is chair of the local branch of the Conservation Society in the village.’ (Table 3.1, N37) Appropriate concerns for the ‘helpmeet’ of a gentleman in the making. Part of her duty is to foster an image of the dependent and indulged wife, the essential accessory for an aspiring gentleman. At the same time, her involvement with worthy causes and her interests in a cultural high ground transmit an upper-middle-class image essential to the construction of his particular masculinity. Like those on the New Right, although Mr A. claims to despise and oppose the traditional upper classes, and the landowning classes in particular, he desires the status associated with their breeding and the superiority it exudes, and aspires to their ideal of power and lifestyle. The contradiction is that their political and financial power is now largely illusory. However, drawing upon a range of masculine working-class and middle-class entrepreneurial discourses and values, most of which hinge upon the role of breadwinner, he thereby reproduces a contradiction not only with the image he wants to foster, but with the lifestyle he wants to lead. The men and the class to which he grudgingly aspires reveal a much ‘softer’ and more feminine masculinity which he admires. The contradiction is that they fail to display the rugged individualism so central to his financial strategies, yet which he appears to despise. Conclusions I have argued that the mainstream literature on enterprise assumes a natural interchange between the men and their business. This is also mirrored in the foregoing case studies where entrepreneurial men tell 110 Class, Gender and the Family Business their stories in ways that conceal several important features about the separation of home and work and the kinds of repercussion this has for both spheres. These respondents deny male emotion, and yet their energies and passions are channelled into the creative process of accumulating capital, rationalised in building a business and reconstituting their masculine identities. These men, who are also husbands, regard their unlimited claim to the space and time away from home as their undisputed right. Workaholism is simply the means to pursue the breadwinning role, the accumulation of capital and the construction of identities. But the impact of this is to free such men from all but the most perfunctory domestic duties, leaving them free to build their empires and embellish their masculinities. Paradoxically, entrepreneurial masculinity hinges upon paternalism symbolised in the patriarchal image of the ‘family man’. It is merely symbolic, for the whole panoply of domestic duties, especially the very demanding business of child rearing, is left to the wife. The men’s patronising (Harvey Jones, 1992) accolades to their wives for giving ‘emotional support’ merely conceal the value and scope of wifely labour, but importantly fail to scrutinise the male claim to be ‘family men’. It is this issue that I now wish to explore in the next chapter. 7 The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life: ‘It’s Like Being a One-Parent Family’ This chapter examines the relationship between domesticity, emotion as absence and enterprise. Drawing on Ochberg’s (1987) argument that contemporary men merely act out their emotional family role, this chapter explores the dynamics of the sexual division of labour and the relationship between home and work. In particular, it draws attention to a neglected dimension, the issue of male emotional investment in the domestic sphere. It is suggested that the male entrepreneurs’ work activity is so pervasive that it invades and colonises, with the subsequent effect of introducing a particular order to domestic life. Such ordering of domestic activity appears as a contradiction for, on the one hand, as the earlier chapters reveal, most enterprising men argue that they draw a very sharp distinction between work and home activity. In this sense, the control of the household seems the responsibility of their wives. On the other hand, as this chapter reveals, such ordering is in itself prescriptive and appears to extend a permutation of capitalist logic to the household. Of course, such men’s absence from the household and their preference for disengagement from the messy arena of emotional work obscure the extent to which they attempt to regulate not least wives’ physical labour, but also the whole remit of emotional management in the service of the enterprise. The sharp separation between work and home seems validated by men’s absence, but this neat division conceals many ambiguities. The demands of the enterprise may reduce men to breadwinners, but it also rationalises the organisation of the household in a variety of ways, particularly the manner in which husbands and wives utilise their emotional labour within the household. As Chapter 6 suggests, men reserve their emotion for activity within the enterprise, but here it is argued that wives’ energies (physical and emotional) are also consumed by the same activity. 111 112 Class, Gender and the Family Business Emotional labouring refers to work done by wives in the private sphere. This includes shielding spouses from domestic problems, acting as counsellors, nurturing spouses’ confidence and relieving them of conventional responsibilities. (The recent proliferation of professional counselling amongst the middle classes is an indication of the economic significance of this work.) The case studies presented demonstrate that wives’ emotional labour is consumed by their husbands/entrepreneurs in the pursuit of business. Such men’s conventional paternal duties as husbands and fathers are largely reduced to that of breadwinner, apparently exonerating them from expending emotional labour within the family. Of course, the breadwinning role is primarily seen as an economic task, characteristically associated with rationality; it dissociates men from emotion and denies that emotion is part of their labour. The control of emotions is part of the construction of masculinity, and middle-class men are often involved in the control of the emotions of others such as their employees. This denial reinforces notions of personal strength, integrity, dependence and personal independence characteristic of masculinity generally. The importance of domestic labour as emotion work to the enterprise has been addressed by a number of writers. For instance, the essence of Davidoff and Hall’s (1987) study is that the Victorian configuration of the capitalist ethos sought through denial and abstinence to shape the conduct of married sexuality and emotionality within the business family household. The consistency of the wife giving support is demonstrated by Kanter (1977), who argues that there is an expectation that the wives of corporate men will create the conditions, through good homemaking and emotional nurturing, for the advancement of their husbands’ careers. In supporting their husbands as organisational men, wives are also required to adopt corporate codes of prescriptive wifely behaviour and modes of appearance, thus allowing the values of the corporation to infiltrate what is conventionally projected as the remit of personal judgement and choice. Roper (1994) signals similar influences when he highlights the significance a wife’s appearance has in influencing the fate of aspiring postwar organisational men, whose careers partly depend on idealised wifely behaviour and the regulation of wifely labour. Finch (1983) conveys the importance of homely tranquillity and wives’ comely deportment amongst public sector professional men. The importance of the wife’s image is illustrated in the previous chapter where the focus on Mr A. shows how the construction of entrepreneurial masculinity, susceptible to change and reconfiguration, The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 113 depends not on only a wife’s support, but also on her appearance and status. To some degree, this is a version of Veblen’s (1925) controversial notion of the ‘idle wife’. The ‘idle wife’ became a symbol of early twentieth-century American affluence and new consumption patterns amongst newly rich industrialists. Indeed, the contemporary parallel of the ‘idle wife’ is the ‘trophy wife’ so dearly beloved by media pundits. These stereotypes portray women as the accessories of rich men. As argued earlier, this stereotyping is problematic for women in various ways, because it denies the extent of the services wives provide in the home. Wives generally carry out a wide range of use-values undertaken in a sphere of consumption (family/domestic/private) seemingly distinct from the enterprise. However, as this chapter insists, the work they undertake, the child care and the maintenance of the household are critical to enterprise. Few of the men interviewed for this study would support the notion of the ‘idle’ wife; rather, they more or less conform to the nineteenth-century image suggested by Davidoff and Hall (1987), who dub the whole range of services provided by their wives the ‘invisible contribution’. These men have very precise ideas about wifely roles and about how they should be conducted. Theoretically, this chapter subscribes to Delphy and Leonard’s (1992) argument that the family is a unit of production organised along patriarchal, hierarchical lines. There are different permutations of this organisational hierarchy, but the husband and wife constitute one. Men as husbands are able to appropriate their wives’ labour because the rules of patriarchal marriage make husbands the virtual owners and controllers of their wives’ labour. This enables them directly to appropriate wives’ labour as their own in what is conventionally regarded as productive work and, as earlier chapters illuminate, transform their wives’ careers from housewives to company directors whilst reversing this pattern with even greater speed. Defined by relations of domination and subordination, the importance of the domestic arena is that it produces and reproduces the conditions and the resources essential for the perpetuation of entreprenuerialism, producing suitable enterprising men and supporting flexible female labour. Insights drawn from Pateman’s (1988) work again highlight the manner in which the marriage institution provides the conditions for these relations and interconnections to recur. The male sex right, cloaked in the duplicity of the marriage contract, provides the mechanisms and is a prime site for male control of female sexuality and indeed labour (see also Engels, 1884, 1972; Erickson, 1993). The foregoing arguments serve to highlight men’s common interest in the control of women’s sexuality and labour, and 114 Class, Gender and the Family Business provide useful theoretical insights into the dynamics of the relationships between the male entrepreneurs and their wives. Of particular concern here are the ways in which the women’s emotional labour has been consumed. Any explanation of the manner in which wifely emotion is consumed by the enterprise must begin with the question of enterprising men and their own emotions. Fineman (1993), Hearn (1993) and Roper (1994) overturn the Weberian image of the organisation as non-emotional. Contrary to conventional accounts of entrepreneurialism, this growing body of literature removes any doubt that emotional labour is part of modern organisations. Indeed, Roper’s (1996) study of male managerial relationships mirrors the basic tenets of D. H. Lawrence’s thinking and the classical vision of the male relationship in that it suggests that male camaraderie clouds the emotional relationship that exists between men. However, the combination of capitalist logic and the contradictions that characterise the managerial agency role constrains the potential of any such cordiality, and in equal measure nurtures division and competitiveness amongst such men. What is really happening is that emotion is put to the service of capitalist rationality, and thus enterprise. But the manner in which this occurs very much depends on position and rank according to the hierarchy as defined by the social relations of production. The entrepreneurial men portrayed in this chapter voluntarily engage and express their emotions in the dialectical process of wealth creation and in the construction of particular masculinities, but, contrary to Roper’s cordiality, are pitted against each other in a competitive process. As Chapter 6 suggests, the entrepreneurial process both necessitates and generates the expression of emotion from such men. However, the question of control separates out such men from alienated workers for they gleefully extol the virtues of being engrossed in ‘their’ world of work. This quest for wealth, and the power that it brings, are seductive, but conveyed in notions of sacrifice and workaholism suggest selfimposed deprivation endured on behalf of family and business. The contradiction is that building a business, whilst being a competitive process, is also an invigorating outlet for men’s intuition, selfexpression, energies and passions. The highly charged emotional games of boardroom coups, business deals and company acquisitions are evidence of male emotion. Yet, while such men clearly show they can be emotional beings they are reluctant to talk at any length about how much they are involved in activities in the home, other than in the role of provider, and respond defensively to any further probing. The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 115 But I want to make a rather different point: that these entrepreneurial men’s relationship to emotional labouring in the private sphere is one of consumption; they are in effect the recipients of nurturing. Kanter (1977), Pahl and Pahl (1971), Pahl (1980, 1983), Scase and Goffee (1989) and Roper (1994) focus on the impact of the separation of home and work and managerial careers, and draw attention to the importance of domesticity and wifely roles in shaping entrepreneurial careers. Kanter (197) and Roper (1994) both illustrate how wives are incorporated into the careers of managerial spouses and the manner in which such women become the unpaid but necessary employees of the corporation. Such wifely support largely involves the extension of the traditional supporting role, when corporate wives uphold male largesse through charitable work, socialising, demeanour and behaviour in line with the corporation’s definition of the wifely role. By contrast, Pahl and Pahl (1971) found that wives were no longer required to share their husbands’ work-related problems extensively or to be socially involved in different aspects of corporate life. Similarly, Scase and Goffee (1989) question the extent to which wives are psychologically immersed in their husbands’ jobs and argue: ‘Instead they are encouraged by their husbands to maintain a ‘safe distance’ from the demands of the job’ (Scase and Goffee, 1989: 153). In their study of corporate managers they found that senior managers were less likely to be home-oriented and that they had invested more of themselves in the business. Roper (1994) argues that managerial men reduced the time they spent with their families in mid-career. Viewed together, Kanter (1977) and Scase and Goffee (1989) suggest that the relationship between home and work is fluid and changing, when in this instance managerial men modify the form of wifely involvement. However, it is important to look at the question from the opposite perspective, for example, how managerial and entrepreneurial men engage with the household and whether this has any relevance for the enterprise. Indeed, Scase and Goffee (1989) and Roper (1994) suggest that such men are increasingly absent from the home. The research presented in this chapter conforms to the notion of absence, but it shows that although such men withhold their emotional labour, they nevertheless draw nurture from the household. In other words, entrepreneurial men are the recipients of nurturing but appear not to reciprocate the process. They depend on their wives to bring about the ordering of emotion work which ought not to impinge on their emotional arena. Ochberg (1987) argues that even when men engage in the domestic sphere, they make little emotional investment. Drawing on role theory, 116 Class, Gender and the Family Business he argues that men are merely ‘acting out’ their conventional economic role: We have left unexplored the possibility suggested here; that men attempt to escape their private troubles by migrating – like souls fleeing diseased bodies – from their private lives into public ones. (1987: 190) Ochberg’s argument is that men’s public role provides them with a route by which to escape displays of emotion. When the logic of acting in role is extended to domesticity, it seems that men are emotionally disconnected. On the other hand, as Connell (1995) observes, power is a feature of role-play and in this case facilitates the extension of rationalisation characteristic of the exchange sphere. Arguably, there is often an attempt to introduce a kind of capitalist rationality to the organisation of emotion work within the household. First, as wifely labour is concerned, there is the expectation that the ideal wife will run the home efficiently, which means taking on the whole remit of domestic responsibilities. Second, it glosses over men’s refusal to confront and find solutions for familial problems. Their work provides the excuse to avoid deeper involvement with problems associated with family life. While workaholism does emanate from the demands of enterprise, it is also endorsed by men’s perceptions of and the boundaries they draw around their domestic roles as family men. This study found that, despite two typologies of entrepreneurial men, ‘the company man’ and the ‘takeover man’, all the men conformed more or less to the spirit of Ochberg’s argument. In this sense, despite a difference in approach to building a business, they all managed their emotional labour in a very similar way: they withheld emotional expenditure from the domestic arena so that it could be consumed in the art of business, but at the same time benefited from wifely support, whilst relying on their wives to compensate for their poor emotional performance as ‘family men’. Absence and entrepreneurial men There is indeed a link between avoidance of emotional involvement and physical absence from the home and workaholism. That such men are able to devote much of their time in the pursuit of enterprise is a result of the power and authority they enjoy as men, but particularly as husbands, in being able to direct and control their wives’ labour. That this The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 117 escapes question is related to the ways in which such men draw on heroic themes of self-sacrifice, which when hinged to their conventional breadwinning role, acts as a powerful defence. The manner in which men come to terms with this is conveyed by Mr M.: ‘Well I used to start work at six in the morning, and I’d work till ten o’clock at night, weather permitting. At other times I’d be away from home for weeks on end. If I wanted to finish a job and couldn’t afford to take time, well I wouldn’t be home. There were times when I didn’t see my kids for weeks on, they were not up before I left in the morning, and were in bed by the time I got home. But my colleagues used to say what a great woman P. was. You could never tell there was a child in the house. It was spick and span and she took charge of everything.’ (Table 3.1, N32) The underlying theme reflected in this comment is the idea of discipline and order which runs through the organisation of his work and home life. Self-denial, discipline and physical endurance are the hallmarks of his sacrifice. This has involved long hours of work and separation from his children. However, the rationalisation of his working life is extended to the organisation of domesticity and there is a sense in which being ‘a good wife’1 too becomes a sacrifice on behalf of her husband’s goals, which means imposing a regulated and disciplined regime upon the family. A good wife must also become ‘hard’, that is, be independent of the need for displays of spouse devotion, but must carefully spare the children disappointment. Since work commitments take priority over social arrangements, wifely skills and co-operation become critical to such men as they attempt to maintain some semblance of being a ‘family man’: ‘I was supposed to take the family to the seaside one Easter. Anyway, I got an offer of a job that had to be done over the break. It was in a beautiful part of the country, in a lovely rural spot and had a river running through it. Well, we had to cancel the seaside and instead I booked P. and the children into a nearby hotel. P. occupied them by taking them walking and learning about wild flowers and plants. They were quite happy with that, they had a holiday and I did my work.’ (Table 3.1, N32) The reality of the ‘family man’ is that such men spent little time with their families, but such absence is a sacrifice for their efforts are expended on behalf of the family. In this context the ‘good’ wife is the 118 Class, Gender and the Family Business husband’s faithful agent and unquestioningly accepts his plan, concealing her feelings and pursuing her duty in his absence. A good wife relieves her husband from the demands of fathering, and in this case negotiated the acceptance of a face-saving compromise between the entrepreneurial father and his children. Typically, the burden of emotion work falls on such women when disappointments can be swept away by the soothing words of the caring wives and mothers, the hallmark of the effective management of emotion work. Of course, men like Mr M. are happy to recall such compromises because they contribute to the rich tapestry of sacrifice. I consider this to be one of the most crucial inputs not only to business development, but also to the construction of self-image, for it allows men to construct not only their businesses, but also their own masculine self-images. Absence from home is a central part of the construction of masculinity and business for the men in each of the entrepreneurial models described earlier. Absence at some point during business development is part of the repertoire of strategies for all the men. Even those who aspire to the caring façade of the ‘new’ man imagery see this as their unchallenged right: ‘I have always been on the move and I used to do a lot of work in Europe and since 1983 I have been involved with this [management buyout], and my preference is to commute with an emphasis on the quality of life. The best arrangement is for me to stay away and be home at weekends. So I don’t involve my wife in business matters. And I’m not chauvinistic at all. It is just that I can only work so long. I am usually in the office about 7.30 in the morning till seven at night. So that is an eleven-hour day and it’s enough. I don’t want to go my back on a Saturday afternoon and feel that I have got to mow the lawn or I have to do this or that. My preference is that I don’t like getting involved in domestic things, housework, gardening, repairs, you know, whatever. My wife looks after the domestic side, she will arrange everything for me. My free time is valuable to me and I want to play a round of golf or have a game of tennis or go to my home in Portugal.’ (Table 3.1, N23) This respondent (an entrepreneur with a Master’s degree in business administration and in the mould of the 1980s free marketeer, with a share in a recent management buyout of a large retail business) differs little from men such as Mr M. Both types adopt a very traditional approach to the division of labour and expect their wives to provide a tranquil home environment, a haven where they refuse to discuss work, The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 119 while they recover from outside stresses. This is reflected in another comment: ‘My wife does not have the experience, exposure or education to understand the business. My education is a specific education. I am an accountant and she is not.’ Typically, this entrepreneur, in his late thirties, is one of three partners in the management buyout of a large manufacturer, and was part of the senior management team prior to buying the business. His adherence to a rigid separation between home and work is justified in his claim that his wife has no knowledge of his enterprise. Another entrepreneur in the mould of ‘takeover man’ elaborates on the reasons he prefers to exclude his wife from work concerns: ‘One major reason is that my wife knows very little about the business and few of the people involved, and that is dangerous. It becomes emotional or emotive if I start talking to her about things she knows little about. The second reason is that if I involve her, she would expect me to act on what she advises. She does not realise that decisions are not made in that way. There are other reasons also, if I start to get her involved that is hard work and, working here all day and then having to keep her informed.’ (Table 3.1, N9) These comments confirm Scase and Goffee’s (1989) arguments and mirror the attitudes of male shopfloor workers (Collinson, 1992). By drawing sharp distinctions between work and home both middle-class and working-class men preserve their right to leisure time. Entrepreneurial men absent themselves again when they come home, as they are members of clubs and societies that do not always accommodate women members. But this demand and claim to domestic tranquillity are also ways of not discussing domestic matters. To admit that the organisation of domestic tasks such as gardening is a wifely duty masquerades as consideration and compensates for the lack of a discussion of men’s emotional work and about what constitutes fathering in conventional terms, and the mundane difficulties associated with bringing up children. It is to trivialise and overshadow real domestic concerns. Insisting that they are the material providers excludes men from emotional work, while also facilitating their access to emotional labour. It is important to question whether the ideology of role differentiation, characterised as it is by a rigid sexual division of labour, undervalues 120 Class, Gender and the Family Business the significance of emotional labour in the processes of masculine entrepreneurialism and capital accumulation. Presenting effort as sacrifice is not only embedded in the breadwinning role, it is also the way for ‘their’ goals to be imposed upon their wives (see also Sennett and Cobb, 1977). The argument that there is a tendency amongst entrepreneurial men to expect their wives to rationalise domesticity is very evident in the idea of the ‘hard’ wife – another defence against absence. A ‘hard’ wife is one who understands and accepts male absence from the home and does not resist by ‘acting emotionally’. For instance, Mr F. in his midforties, owns a large business located in speculative construction, estate farming and motor cycle manufacture. In the mould of the ‘takeover man’, he is representative of working-class masculine entrepreneurialism. He entered the construction business when he was seventeen, because amongst other reasons he wanted to prove to himself that he was physically fit. His concern with fitness and the power of the body stemmed from a childhood illness and long periods in hospital. This also had damaging repercussions on his education and he did not achieve academic success at school. As he explains: ‘I started work as a plasterer when I was seventeen and learned the skills. I did that for two years and then decided to build one house. Having done that I went on to build two and took it from there. I work hard. I don’t believe anyone needs to starve, there is work there. Of course, my wife thinks I should be home at five. This is what she was brought up with.’ Interviewer: ‘So you married before you entered business?’ ‘No not at all. I had that up and running for ten years before I got married.’ Interviewer: ‘So what is the difficulty?’ ‘Her father was home every evening. But I have a business to run. She has the house to run. She should understand that. A business in today’s climate cannot be neglected.’ (Table 3.1, N30) Workaholics pursue their work with such tenacity that it desensitises them, so that other aspects of their life are taken for granted. Wifely complaints are explained as the result of inappropriate socialisation and the ‘soft’ masculinities of fathers. Claims to workaholism, which is essentially activity outside the home, have long been associated with authentic masculinity. But the underlying issue is about the dynamics of the power relationship between the spouses and the ownership and control of wives’ labour. By refusing to meet the five o’clock deadline The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 121 men create time and energy for themselves. The claims that ‘real’ men do not leave work at five o’clock are ideologies masking the exploitation of wifely labour and the construction of masculinity. Men’s absence from domesticity reveals how capitalist logic creates divisions between ‘hard’, unsentimental, rational men who strive to succeed and ‘soft’ masculine creed men who do not. This is illustrated in Mr K.’s criticism of his wife’s father, who he thinks lacks ambition and drive. The underlying bitterness in this comment stems from Mr K.’s dissenting wife and her refusal to understand and appreciate his efforts. She does not offer the support and nurture that he feels he deserves and fails to understand the reason for his absence. Keen to portray himself as a man amongst men, Mr K. emphasised that the obstacles of childhood ill-health and limited education were overcome by his personal strategies of relentless hard work, physical fitness and strength of mind, achievements that his wife does not appreciate. These values and practices are also intended to be reflected in his dispassionate and unsentimental approach to safeguarding his business. If this means time away from home, then so be it. Again, the theme of sacrifice resonates through his argument. On the surface, the logic of his view of his wife’s contribution is that she undertakes the management of the household with seeming equal dispassion. In this sense, a ‘hard’, sensible and ‘rationalised’ wife makes her contribution to his sacrifice and uncomplainingly carries out her duties, whilst offering support and concern. The importance of comments such as these is that they offer some tentative insights into the extent in which the enterprise shapes the conduct of family lives. Entrepreneurial men are driven by the competitiveness of the market and the need to sustain their enterprise. On the other hand, the household as a sphere of male power accommodates such men’s control over the allocation of their own labour and the labour of their wives. This in turn enables them to reason that a wife’s job is to look after the household. As another entrepreneur put it: ‘When we met my wife was a sister [senior nurse] and had a busy and interesting job. But my preference at the time was that she stayed at home. I see myself as the provider and the one that needs to take responsibility for financial matters and forward planning. I guess that is about it.’ (Table 3.1, N14) This comment suggests that such men limit their input into the domestic area and echo Scase and Goffee’s (1989) and Roper’s (1994) studies 122 Class, Gender and the Family Business of senior managers who confine their domestic role to one of breadwinning. The prominence that such men give to wifely work is sharpened by their own absence, when home-making, child rearing and the image of the family enterprise are strategies intended to increase profitability and ensure the preservation of such enterprise. Entrepeneurial men and rights to nurturing One of the more interesting themes to emerge from the study is that first-generation entrepreneurial men see the receipt of nurturing as their right, claiming time for themselves as opposed to giving time to the family. In exploring the question of whether time was allocated to his family, one respondent, the partner in a management buyout, said: ‘Not consciously. They ignore me when I walk in.’ This typifies the defensiveness of many of the younger entrepreneurial men when challenged with the question of emotion work. On the face of it, this comment suggests that the respondent is ignored and isolated by his family, and is in some ways a victim of his absence. In trying to turn round a pattern of relationships that, on balance, suggests that male partners have more leeway to define, there is an attempt to relocate the issue of interests. Undoubtedly exhausted by the stresses and strains of work, such men see home as a space in which to take work concerns on to another plane. In other words, home separated from work is most desirable when it provides an uncluttered environment and a space ‘for thinking time’: ‘But also the mind freewheels, sometimes and it is nice to go home and have the time and space to let the mind work out a problem.’ (Table 3.1, N9) In this sense entrepreneurial men have a particular interest in the way wifely work is performed. Home time needs to be free of fatherly demands so that such men can engage in thinking time and problemsolving. Another entrepreneur said: ‘No, no, I don’t work all the time, but I guess I’m thinking about work things all the time. I don’t class it as work.’ (Table 3.1, N14) The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 123 But further probing reveals that a thinking time environment can be achieved only by insisting that wifely work remains an exclusive female concern: ‘I see my wife as a mother and housewife. That’s her job. That’s probably not satisfactory to her. And she is trying to find things to do to occupy her, well no . . . she’s busy with the children, I mean something to interest her.’ (Table 3.1, N9) However, the imposition of a rigid division of labour is a source of conflict and wifely contest, for, as the comment shows, such men resort to traditional stereotypes of the complaining wife. Typically, such men argue that each spouse has a separate job to do, and there is little reciprocity concerning the work pressures generated. This respondent implies that he does not expect emotional labour to be expended on him personally and is quite unprepared to engage in the emotional labour essential in the reproduction of domesticity, yet he is the recipient of emotion work. One of the central dynamics of such partnerships is the potential conflict and contest about the allocation of emotional labour. It is a rather subtle demonstration of the way a husband’s goals can be mediated to control a wife’s labour within marriage. Of course, the withdrawal from emotion work and such men’s insistence that their wives confine themselves to motherhood and wifely careers is the other side of workaholism. It goes beyond Ochberg’s argument to suggest that such men simply slip into another role, for it seems that they make little pretence of trying to share their wives’ concerns, but rather want freedom in the domestic space to extend their working hours or enjoy leisure. Entrepreneurial wives and emotion work Entrepreneurs are not always prepared to admit the cost of their absences from home and their emotional withdrawal and the repercussions of their imposed expectations and goals on their wives. Women, regardless of whether they are business partners in the enterprise or not, bear the burden of domestic organisation, housework and emotion management. Despite claims to workaholism most men have leisure time and are more likely than women to belong to clubs and societies. As Burt’s (1992) notion of structural ‘holes’ illustrates, some of this is work-related and afternoons on the golf course often enable a social 124 Class, Gender and the Family Business occasion to be transformed into business opportunity. In contrast, there is no similar pattern of duties for the wives who are directly involved in the business. The operational character of wives’ work confine them to the workplace. For instance, this wife is an operational manager in businesses that comprise enterprise in the financial sector and estate agency, and as this involves client entertainment: ‘It’s like I stay home [in the office]. There is a lot of entertaining to do and my husband enjoys that. He has lunch appointments nearly every day. Of course, he has little to worry him because I like him to see to our clients and I sort things out here.’ (Table 3.1, N25) Entertaining business clients can be a combination of work and pleasure but is largely a husband’s responsibility. In instances such as this it seems that wives have drawn on the issue of business entertainment as a means of negotiating a sustaining role in the enterprise. Similar to the division of labour characteristic of the business partnership, by taking on a backroom role, however ruefully and resentfully, such wifely compromises create opportunities for quasi-leisure time for the partners, and are another manifestation of seeking to protect and shield their spouses. In some ways, examples such as this are tentative illustrations of the ways in which wife/partners extend emotion management into the business arena. Women in business partnerships have relinquished their leisure time. Correspondingly, the most cherished wish of such women is a little free time to devote entirely to themselves. A wife with a directorship in clothing manufacture said: ‘I love to read, and there is nothing that I like better than to take a book into the bathroom and have a really hot bath and a good read. I know that sounds boring, but it is my greatest luxury at the moment.’ (Table 3.1, N10) Although the wives at no point made claims to notions of sacrifice or workaholism, often what passes for leisure is really work: ‘The only day that I reserve as a leisure day is Sunday. I sort out the household bills and F. likes a game of golf or to go fishing. On a Sunday I do bits of gardening and, of course, I do all the meal planning and the cooking for the week. In the morning I do casseroles and curries and freeze them in preparation for the week ahead. But I don’t think of this as work, because The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 125 it is just a case of getting it all ready in the morning and popping it in the various ovens and it looks after itself.’ (Table 3.1, N7) This shows that the ideology of housework as non-work influences the way women think about and define the work they do. Examples such as this also show the extent to which domesticity has been rationalised, when family evening meals are planned and cooked in advance at the beginning of each week. Even the rationalisation of cooking for the family does not extend wifely leisure time but rather enables such wives to manage the double burden of home and work. While Segal’s (1990) study amongst double-income professional couples suggests that male partners recognise the demands of their partner’s careers, it is telling, perhaps, that she also reports that such women obviously substituted their own labour by hiring cleaners, nannies and cooks, as opposed to achieving a more equitable redistribution of domestic work between such couples. What this suggests is that professional women with equal and independent earning power are able to wield more influence over the organisation of domesticity. By contrast, whilst most of the entrepreneurial wives interviewed hired cleaning help they were responsible for cooking family meals: ‘The most exhausting thing for me is to have to cook the family meal at seven o’clock in the evening. I had a cook at one point but no one liked her cooking and there were so many complaints that I decided I’d do it myself.’ (Table 3.1, N33) It could be argued that this is an example of workaholism amongst such women, but as it reflects a standard pattern of working, it is taken entirely for granted. However, it is not the lack of leisure time that is a matter of concern for such women but the recognition of the need for some degree of reciprocity in emotional support. For instance, Mr M.’s accolades to his wife’s virtues as his domestic ambassador conceal the hurt inflicted upon his wife. In a discussion about the problems of adapting to great wealth and success, Mr M., and indeed his children, revealed that ‘Mother couldn’t take it’. As a result of this pressure she had become overweight and ill. It is not difficult to see that Mr M. correlated his version of successful masculine enterprise with personal fitness and good health, a precedent his wife failed to meet. In a paradoxical way it parallels the feelings of some of the wives who complained that they are expected to retain their sexual attractiveness while also being exhausted by work. The men interviewed here 126 Class, Gender and the Family Business conformed to the very traditional pattern of seeing their wives in the conventional setting as their wives and the mothers of their children, engaged in caring and nurturing work. This raises many questions about femininity and the notion of the male as the family patriarch and the protector of women. The wives’ experience of emotion work is contradictory and doubleedged. On the one hand, women are aware that they are transformed into a ‘sacrificial lamb’, and, on the other, they collude in this for they continually shield their husbands from domestic troubles on the grounds that they want to save them from further stress. The wife, partner and founder in an expanding insurance and property business recognised this: ‘Well of course, behind every great man there is even a greater woman, you know, the “little woman”. You are the one to do all the backroom work. I mean here at home, I am behind him. Because even if they don’t bring their work home, they bring their worries home, and they don’t even have to tell you. You know and of course then you have to make allowances for that. And if there is something you need to talk about – well you don’t because you think, “I don’t want to bother him”.’ (Table 3.2, N36) This may represent the other side of ‘male thinking time’, when entrepreneurial men seek refuge in the security of domesticity from worldly pressures. However, the comment demonstrates how the public sphere gradually invades the private sphere. This does not need to take the form of sweated manual labour. It is much more subtle. Acting on the capitalist impulse consumes the entrepreneur’s own capacities, space and time. The wives of men in this situation consider it unreasonable to insist on reciprocating conjugal support. Seeing their spouses under pressure through what are their legitimate breadwinning activities, wives are forced to relieve their husbands of the burden of domestic matters. The wife and co-founder of a men’s clothing and more recently property speculation business explains: ‘I found it very, very difficult and there are times when I have got very upset and resentful. I don’t think you can avoid it. At one point the youngest boy became very difficult. He had tantrums each morning before school. It wasn’t that he had problems at school. He was perfect there. I went out of my way to please him, and I used to take him fishing, even on the coldest days. But I think a lot of C.’s problems are in his personality and the way I’ve handled him. Anyway, I got to such a low ebb I had to find someone The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 127 to talk to, because when I tried to tell T. [spouse] he’d say, “Oh, do come on, you really must put your foot down, and make him do as he is told,” and off he’d go to work. In the end I had to tell C.’s form teacher, and it was agreed that T. would get involved and try and sort the problem out. When we left the school, T. said, “I’m sorry, I hadn’t the slightest idea what you had been going through”.’ (Table 3.1, N9) This comment conveys some sense of the extent of the entrepreneur’s investment in emotional work. Emotionally shut off in his world of work, and despite his wife’s constant pleas for help, it was not until the problem was presented to him by an outside agency that it gained his attention. This example gives credence to the arguments debated earlier – the extent of the power husbands have over their wives’ labour. The kinds of sanction open to wives in such situations are fairly limited if they are to maintain the semblance of a cordial and happy marriage, set against the institutional powers and privileges granted by marriage to husbands and the conventional duties it imposes on wives. This is a most interesting example, because this spouse telephones his wife very frequently and appears attuned to his family’s needs, thus reconstituting the notion of the family man. However, much of the communication is business-related. So not only does the wife take on what might reasonably be regarded as the husband’s share in domestic matters, she is also involved in the business. Acting as his personal assistant she carries out a series of tasks, some of which are secretarial and others can be categorised as public relations duties. In addition, she does a lot of business-related entertaining at home, including having her spouse’s business partners and clients to dinner. What is interesting is the manner in which she trivialises the significance of this, passing it off as ‘merely cooking a bite of supper’, since such gatherings are informal. At the same time, this creates the cosy image of the dedicated and involved family man. This example mirrors Ochberg’s (1987) professional men ‘acting’ in their domestic role, who were not contributing as much as they might. But wives do not necessarily see it like this: ‘I think in a way, I mean part of it is not T.’s fault, because part of it is down to me wanting to protect him from it, not wanting to bother him with it, because he has got so many other things to worry about.’ (Table 3.1, N9) Frequently, such women feel guilty and a failure, if they are unable to meet the expectations of being a good wife and mother. Yet 128 Class, Gender and the Family Business interviews with wives also repeatedly demonstrate that discourses about ‘protecting’ men run alongside resentment. This discourse emanates from the conventional expectations and duties a marriage imposes upon a wife, and especially the tacit manner in which a husband can impose his expectation of the ‘good’ wife. But the other side of not complaining is sometimes interpreted as an act of wifely rebellion. This respondent, the partner and founder of the insurance and property business, said: ‘So, I’m sort of rebelling with the two people, my daughter and my husband. But with him I don’t tell him now, because unless he makes an effort, there is no point.’ The rebellious wife refuses to inform her husband, thus depriving him of information essential to maintaining his role as patriarchal controller within the family. The wife takes on the responsibility of disciplining their daughter, and thereby undermines his authority. Despite the husband’s ambivalence about sharing emotional work, this comment also expresses guilt, for the refusal to consult is seen as subversive and inappropriate behaviour according to the ideal of the ‘good wife’. Acting out the prescribed role of the ‘good wife’ is characterised by many contradictions. For instance, she feels guilty because she recognises that this is a challenge to his authority. But the pressures to conform are strong, for during further rationalising of the situation, she finally exonerates her husband: ‘But you see, I know he works hard and on top of that he’s interested in various types of sport and other activities.’ In part, this comment corresponds to Hochschild’s (1983) study of flight attendants where it is suggested that women’s greater tolerance of passenger abuse is the result of their powerlessness and inferior economic status relative to men. It is important to distinguish between women workers and wives, for the latter experience restrictions associated with status and duties unparalleled in the experience of women workers or indeed single women. Regardless of whether wives attain economic independence, wifely status assumes an unparalleled subordination to a man in exchange for nurturing duties, which takes precedence over other considerations. The institution of marriage give husbands enormous power over their wives should they wish to exercise it, a point convincingly made by Pateman (1988) and Erickson (1993) among The Entrepreneur’s Wife and Family Life 129 others. But, of course, the means by which wives’ labour is directed by husbands takes a more subtle form than mere coercion. Husbands’ investment in workaholism can often be a smokescreen for their refusal to engage in emotional work and family responsibilities while they still manage to have leisure time. Exclusive male clubs and male-dominated sports activities constitute the playground for many entrepreneurial men. What seems clear is that the question of leisure time separates wives from husbands, while ambivalence amongst women stems from normative expectations about the sexual division of labour. However, such ambivalence is often articulated as resentment, when wives question their own sacrifice in the pursuit of male material success: ‘That’s what I fear most. My husband keeps telling me, “All right, after I have done this, we’ll settle down and do things together.” But to be realistic, I can’t see that happening. He’s a workaholic, he just can’t keep away from work. It’s addictive. It gets in deeper and deeper. I don’t want that in my life, because no matter how important the sacrifices I have made, they are not living inside it.’ (Table 3.1, N17) There is indeed a clear-eyed recognition that they have given up personal goals so that their spouses can pursue their life-chances as capitalists. However, as the businesses grow, so does the polarisation of labour, with the women taking on more and more emotional labouring while male breadwinning is rationalised as an obsession, but yet becomes acceptable, particularly when tied to the discourses and ideologies of sacrifice. Women then question the pursuit of material goals, if the quality of family life is undermined. This emerged as a dominant theme among the women interviewed. The price is often too great: ‘Yes, as the family grow up, and the children are very small and your husband is building up a business it is very hard on the wife, it is like being in a one-parent family.’ (Table 3.1, N17) The result of this is to reinforce a rigid sexual division of labour, whereby men’s increasing involvement with entrepreneurial activity greatly overshadows domestic involvement with their families, except in an extremely narrow sense as economic providers. Wives take on disproportionate responsibility for the emotional and reproductive work which is essential to the processes of wealth formation and to the construction of entrepreneurial masculinities. 130 Class, Gender and the Family Business Conclusions This chapter has drawn attention to the significance of emotional labour in the domestic setting and argued that, although it remains largely invisible, it constitutes a major resource for the enterprise. Emotional labour as a resource frees male energy for the enterprise, whilst sustaining a pool of energy via wifely support. Emotional labouring is in itself a gendered process whereby male entrepreneurs are able to exclude themselves even from conventional emotional tasks associated with fathering. In looking at two types of entrepreneurial masculinity, despite the differences between such men, it is argued they had equally drawn upon and largely benefited from the domestic exclusionary practices they operated, while still benefiting from the processes of family production and reproduction. The men benefit from continuous personal nurturing, which in itself is a direct contribution to the enterprise, and although it is an essential part of the broader business strategy, it remains invisible. The discourses of workaholism, ‘family man’, and so on, both conceal and amplify the significance of the wives’ emotional labour, enabling such men to prioritise business activity in the public sphere. The men are invariably psychologically separated from what happens in the household. This may not be an intentional strategy operated by such men, and should be understood in the context of an entrepreneurial culture when the competitiveness and the gains of the market become too hard to resist. It seems that the process inevitably captures such men making their separation from domesticity inevitable. Although the men differed in terms of class, ethnicity, age and education, they all engaged in the same gendered strategies in their relations with their wives and the household. 8 Women Owners: Honorary Men? This chapter focuses on the five independent female business owners who between them are the principal proprietors of four businesses. Two of the women were sisters and owned one of the businesses; the other three are single proprietors. These businesses are distributed across categories of ‘new’ and ‘old’ wealth and are in a range of economic sectors including plastics manufacturing, organic cosmetics, livery and estate ownership, combined with corporate entertainment. In contrast to the mainstream literature, the importance of Goffee and Scase (1985) and Allen and Truman’s (1991) pathbreaking work is that they begin to address the issue of women in business. However, both studies convey the sense in which female businesses are separate and distinguishable from mainstream (male) enterprise. Goffee and Scase (1985) report that women in business operate somewhat differently from their male counterparts, whilst Allen and Truman (1991) suggest that female enterprise is predominantly in the service sector. In contrast to these findings, it is argued that similarity as opposed to difference with male-headed business describes female-owned enterprise in terms of business type and managerial approach. In examining their approach to business it is argued that these five female entrepreneurs adopt the male middle-class entrepreneurial model to successfully establish, manage and preserve the ownership and survival of their enterprise. Amongst the 70 owners the five women are unique for they seem to have ignored or overcome their gender constraints in the masculine business world. For instance, out of a total of 44 ‘new’ businesses, only two first-generation businesses, the livery and the cosmetics enterprise, have been established by women and continue to be managed and owned by them. These two women are remarkable for they have of their own volition, and against all the 131 132 Class, Gender and the Family Business odds, defied convention and entered the male world of business. The third female-owned enterprise, a ‘new’ business in plastics manufacturing, was bequeathed by the male founder to two of his daughters, who have undergone a training and socialisation typical of the male apprenticeship model. The fifth woman, in the absence of a suitable male heir, inherited a title, a large country house and land, constituting the only female owner amongst the 15 landed sector businesses in the ‘old’ wealth category. Despite the central role played by female kin, apart from one woman who had a senior managerial position in the Irish business, there are no female owners amongst the 15 ethnic minority businesses, and the five women proprietors are majority white. Women and the entrepreneurial model In this section it is argued that the notion of a shared business culture (Mulholland, 1997) is appropriate in the examination of women’s entry into business. In this sense it is suggested that like their male counterparts such women benefit from the material attributes of a middle-class background, which, in a rather distant but important way, helps them to cross conventional gendered class boundaries. Like men they also acquired particular kinds of knowledge and skill specific to the business they subsequently entered. In this sense, their business entry is preempted by their cultural capital and training. The female entrepreneurs are similar to men in a second respect: the management of business finance. Risk-alert, the women entered businesses that required little initial capital outlay, or drew on family resources, but necessitated particular kinds of expertise and access to cheap labour. However, it was personal interests combined with entrepreneurial flair that stimulated the initial business start-up in the case of the two independent women wealth creators discussed next. Born in one of the Midland counties, Mrs B. spent her childhood in Northern Ireland. During her time there she developed an interest in horses: ‘Well, I have always been dealing with horses. It all started when I was at school and my friends at school had different horses. I used to go to Ireland on holidays and realised that every summer when I went back they had different horses. They raised them and sold them. They were all starting new ones and I thought this was fun. When I was seventeen I asked my father if I could try it and do it once with one horse. I made a lot of Women Owners: Honorary Men? 133 friends in Ireland, so we went to Wexford and bought my first horse for £70 and sold it for £120. I went on from there. I was lucky with my first horse and got the taste for it.’ The importance of this is that it replicates the pre-entry experience, or apprenticeship, characteristic of the male entrepreneurs. This initial interest in breeding and trading in horses is a learning process, which is slowly and cautiously developed. At the same time business growth is facilitated organically, behaviour which shows a marked similarity with male entrepreneurial behaviour characteristic of the company man typology. Marriage is an important turning point for such enterprising women. Unlike the wives in male-headed businesses and similar to male business heads, such women benefit from emotional support from their spouses and the complementary role played by such men, first, in providing a business partner marriage facilitates business expansion. For instance, marriage helped Mrs B. to transform an interest into a growing business concern: ‘My husband was a soldier but his father had been involved with the polo world and bred horses. We bought around 100 acres of land, the house, the stable yard and diversified. We started a riding school, and we raised and schooled horses. We trained hunters and jumpers. We also boarded horses. We had that interest which was just great.’ In this case, the importance of marriage is that it provides a business partner who shares an understanding and interest in horses. What separates this woman from other business wives is the ease with which she assumes the centrality of her role in the business and unquestioningly sustains it through subsequent phases in business development. However, whilst the business hinges on her technical and financial skills, her role is sustained by her passionate interest in horses and entrepreneurial flair. Mrs M. is chair of a skin care cosmetic business serving a niche market, but has been a dairy farmer, a property developer and high fashion designer and retailer in the 1960s. However, she started out in clothing manufacturing in the 1930s and has over 60 years successfully diversified into other business sectors. Similarly, it was Mrs M.’s class background, training, creative flair and the need to articulate these that seem to have precipitated business entry. However, her training appears to correspond closely with the notion of the male apprenticeship: 134 Class, Gender and the Family Business ‘I suppose I was the product of the College of Arts and Crafts. I got a scholarship and while I was there, I was sent off to be interviewed by a textile company for a job in design. I got on well and saw different sides of the business. I was designing clothes. At the time no one thought that L. could do anything but socks and stockings, but I showed them an alternative. I designed such amazing clothes and applied that design. But what I really wanted was to start out on my own. I suppose I inherited my creativity from my father. . . . We are all very artistic. I was itching to go.’ However, the transition from employment to business entry was facilitated when Mrs M. married: ‘I broke away from P. when I got married and we formed our own company together. I was the designer and I hired staff. They all wanted to work for me. I set up a crèche at the company and women came in and worked contentedly knowing their children were close at hand and cared for. Yes, I must have been one of the first to do this. He [husband] was the salesman and sold the products and it worked out very well.’ This pattern of organisation and management of this business replicates male-headed businesses, except that the woman casts herself in the pivotal role of managing director in a way that is similar to the selfmade man model. Yet, this structure is also a configuration of the conventional sexual division of labour, for despite remaining head of the business, stereotypically she took control of the creative side, the product design and the day-to-day management of the business, while her partner/husband met the challenge of the market. In order to alleviate problems with the recruitment of women, she took what seems a revolutionary step and set up a company nursery. Other womanfriendly projects included a grocery-ordering service and a hairdressing outlet. Characteristic of their male counterparts both women take for granted the resourcefulness of their social class attributes. First, they both benefited from a middle-class education and socialisation, which seems to have given them self-confidence. What is remarkable about these women is that they seem oblivious to the obstacles they faced and rather utilised the material resources available to them to best advantage. Of particular significance has been the family, which has been the key funding source for the initial enterprise. In the case of Mrs B., the investment her father made in the purchase of her first horse facilitated her Women Owners: Honorary Men? 135 entrepreneurial flair. Similarly, Mrs M.’s family provided the finance for her clothing factory: ‘Well, my family were artists and liberals and owned a lot property in L. and my grandfather had land. I don’t remember borrowing any money from the banks. No. We just built up. I have never really believed in that. I always felt that was the sort of thing hung around your neck and you could not get rid of, so it was something we never did. We went along creating our own money and spending it when we had it.’ Risk-aversion, with a preference for organic growth, again demonstrates similarities with her male counterparts in retaining the autonomy of the enterprise. This allowed leverage in decisions about the direction of the business and is reflected in product innovations and subsequent shifts into new products. In the Second World War Mrs M.’s business partner/husband joined the RAF as a pilot and subsequently was killed. Such a momentous event might have had consequences for the fate of the clothing business, but Mrs M. took on new staff and carried on. Eventually she sold the business and moved to London, but retained the company name. This astute move shows her sensitivity to changing tastes and business acumen. Passionate about fashion, she continued to work on design and in the 1960s sold them on for mass markets. However, she also opened several boutiques in London which retailed more exclusive clothing. Emblematic of her success was when, in 1965, her daughter, a model, wore one of her op-art, diamond-patterned suits to Ascot. She also regularly travelled to America marketing her designs and products. Female entrepreneurs and business development In developing the livery enterprise, Mrs B. has combined her passion for livestock with the growth in rural leisure. She has developed business networks in Poland and Ireland seeking out the best horses for the different aspects of her enterprise which includes an equestrian centre, a livery service and a substantial landholding. The 1980s affluence marked a temporary period of business expansion for this enterprise, witnessed by the entry of the socially aspiring and newly affluent classes which reshaped the rural leisure industry. Sensitive to the fragility in constructing an enterprise on such a precarious economy, Mrs B. said: ‘People think I have been doing well. You know everyone now owns a horse, wants to go riding and be seen having a day out at Ascot. But for these 136 Class, Gender and the Family Business people it is something new. I mean, they said anyone can be a member of Lloyds and they had the butcher, the baker and the candle-maker. With the recession these people just disappear.’ Undoubtedly the volatility of the market raises questions about the continued buoyancy of the enterprise, but Mrs B. has already made considerable budget adjustments through staff reduction. Nevertheless, her capital assets remain considerable and it seems that she has offset such income reductions through her international networks which has helped her with the breeding, trading and training of horses. In the early 1970s, Mrs M. sold her fashion business and moved to the countryside. She bought an old, run-down vicarage, an adjoining holding of land and herd of dairy cows. Again in tune with changing market tastes, she was able to combine her business acumen with her creative drive: ‘People began to want better and more natural skin care products. They were anxious about their skin and I have been interested in seeing how beauty products could be made using more natural ingredients.’ Mrs M. is quite innovative and simply channelled her creative energy in another direction. With a keen commitment to the environment and green issues her aim was to make beauty products that were not tested on animals. Having experimented with milk she soon realised that it formed a good basis for a range of skin products. The project spiralled from there: ‘I eventually found a Swiss chemist who was prepared to work with me on my recipes.’ Over the last twenty years she has vastly developed the product range, which now includes 70 different skin care preparations. They are manufactured and distributed through mail order from her home to 60,000 customers in the UK and elsewhere. In terms of the three phases of business formation, what distinguishes both women from the wives in maleowned businesses is that once they have created the business, they easily assume professional and entrepreneurial roles. In the case of Mrs M. she has combined her technical skill with her creativity and has taken the name forward under different business configurations. In contrast to the other wives in the study, these two women appear to have averted the negative impact of gender power within the marriage and have Women Owners: Honorary Men? 137 managed to retain their ‘public’ sphere positions. Nock (1998) argues that marriage constitutes part of the rite of passage to masculinity for men, who as the earlier chapters have shown have benefited from the inequalities that stem from marriage. In these two instances, the women appear to have reshaped the balance of power within marriage in ways that facilitated their entrepreneurial roles as business heads. Women and management: stepping into your father’s shoes Two of the women inherited one of the businesses in the ‘new’ wealth category, the plastics manufacturing concern in the early 1990s. Their father had set up the medium-sized business in 1946 in a tiny workshop and with very little capital and much zeal, drive and the help of family labour developed it into a medium-sized concern with international subsidiaries. It employs 200 people and had an annual turnover of £8 million in the early 1990s. He started by producing industrial mouldings then, with experience innovated in design and diversified highly successfully into toys and games, and sold in global markets’. However, the management structure and style typified the family firm with the founder holding executive roles. The second feature characteristic of the family firm was the heavy dependence on family labour. Like the contemporary ethnic minority small business sector, Mr X. hired aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters and positioned them vertically and horizontally in jobs across the company. As Chapter 9 explains, the effects of the privileging of male kin in the family enterprise via a gendered male apprenticeship, the key characteristic of the notion of a shared business strategy, is to exclude female kin. However, in exceptional circumstances, family women are invited into the business for strategic roles in leadership and eventual ownership and they undergo a training that appears identical to their male counterparts. However, the central question is whether this prepares them for such leadership roles. The next example focuses on how two family women became owners of a plastic manufacturing business. In this case, and similar to their male counterparts, both women went to a leading public school for girls. However, they were doubtful that it had any advantages for them. As S. explains: ‘Yes we both went to A. College. I had started on ten ‘O’ levels and thought that I’d get them and maybe two ‘A’ levels. At the time I was thinking about being a vet, and my strongest subjects were in the sciences and I 138 Class, Gender and the Family Business went to my science teacher and mooted the idea. I remember being told that A. ladies did not become veterinary surgeons. After that I got a little bored. So this school didn’t work out for me and I left and did my GCEs elsewhere.’ While it is not unusual to find that a school’s values are often at odds with pupils’ desire for personal freedom and sense of space, in this case the developing cleavage was rooted in a more rational dimension. As her sister, J., elaborates: ‘Well, the discipline was tremendous, we weren’t allowed to be independent for one thing. We had been brought up by my father and although he was miserably strict, it was balanced. I mean very importantly we were given responsibility. My very first task for E. [the company] was to take care of the fridge. I never liked my school. I was always interested in industry and I have always perceived myself either running my own business or heading up a large company. But that comes from having a parent whose life wholly and solely circulates around running the business. It rubs off on you from an early age.’ This comment suggests that the socialisation of business values, which began for these women quite early with the nurturing of a sense of responsibility and independence, when pitted against the values of the school, produced profound contradictions. It is clear that these women’s values were already formed by the time they entered the school. They had both internalised the importance of responsibility and independence which seems incompatible with the school ethos. Implying disapproval, the disappointment over career advice suggests a rather restrictive outlook in terms of career choices for women. In stifling the progress of their anticipated development, this rather limited evidence suggests that some leading single-sex public schools are not necessarily the best education route for women with ambitions to take senior and entrepreneurial roles. Gender difference seems critical in this instance, since, as Chapter 9 reveals, the public school system, when aligned with other practices, significantly contributes to the rite of passage for men with similar ambitions. This shows that even when families implement equitable opportunity systems for female kin in leadership roles within the family enterprise, the gendered opportunity structure characterising the male rite of passage to leadership can, at critical junctures, present difficulties for women. Women Owners: Honorary Men? 139 In other ways the women’s experience mirrors their male counterparts’ and they insist that the learning process is an all-consuming experience: ‘Well, you see, if you were to look at S. and me, we are not domesticated in any way, shape or form. I would have thought that women in business would have gone through the role of working for other people and would have to look after themselves and would have to run their own households. Well it’s a strange thing that you have got two girls who couldn’t look after themselves. All we know is work and work and our roles within the family business.’ Distancing themselves from domesticity and emulating the male role model on leaving school they both joined the company to work fulltime. Like men in the family business they were trained by their father: ‘After leaving college we were both invited to go in with my father. He started the company in 1946 and he had no sons, so he asked his two eldest daughters to come into the company.’ The training was quite strategic and they were prepared for different roles within the enterprise. The elder sister, aged 33, was expected to take responsibility for the direction of the enterprise, while the younger sister, aged 31, had a more technical training, managing the operational and manufacturing elements of the enterprise. In order to prove worthy of such a challenge, the elder sister set up two independent businesses and managed these alongside her executive duties in the family enterprise: ‘I am slightly different to J. and when I left school I came to work for the company, but not full-time. I was interested in rural businesses and I wanted more involvement in running the family farm. I separated some land from the family farm and set up a training establishment for young people. Instead of going to agricultural college they came to me for six months and had hands-on experience.’ The significance of social class attributes cannot be overstated in this instance. Privileged by being able to draw on considerable family resources, this woman avoided many of the difficulties women face when attempting to fund their own enterprise. As she required a high capital investment, of particular importance was the availability of a 140 Class, Gender and the Family Business portion of land from the family farm, the essential component in such a business. This tremendous resource facilitated an easy entry and startup. This meant that the main financial imperative was to ensure that the turnover was sufficiently robust to cover running costs since there was no capital outlay to recover. Moreover, privilege is reflected in the character of the business which resonates of a life-style enterprise enabling her to incorporate her love of horses and livestock with financial interests. Access to material resources separates those women who succeed from those who fail, for women with few resources were repeatedly unsuccessful in their attempts to raise investment capital. However, the particular advantage of setting up and managing a separate business for this woman was that it acted as the precursor for a position of leadership and decision-making. By contrast the second sister’s training was concentrated in the routine management of the operational enterprise. At the behest of their father, both women and especially the second daughter learned about the technical and operational dimensions of plastic manufacture: ‘It was very important, especially a woman working within the company, that you have experience of things like the tooling and the drawing office. I actually made it the hard way, as a teenager moving through the different divisions, the tool-room, drawing office, the studio and all the different in-house functions. I think that was good. I mean my father wouldn’t have accepted S. as his right-hand man if she hadn’t gone this route also.’ Typically, entrepreneurs in the ‘new’ wealth category who intend to include their female kin in strategic managerial positions ensure that they experience the more unpleasant and arduous tasks. Equally, such women must demonstrate their endurance, commitment and appreciation of both the privilege and responsibility of running a business. However, like their male counterparts, they reject the silver spoon syndrome and insist that merit and hard work account for their positions of power. Despite their inclusion in the male apprentice formula the actual takeover of the business was precipitated by a crisis, with the sudden illness and early death of the founding entrepreneur. The management changeover presented a challenge for both women. They had the choice of selling on their share in the enterprise or attempt to replace their father. ‘We never had any thoughts about selling the business. We have always known that we would continue. Where are you going to put the money? Women Owners: Honorary Men? 141 We could invest in something else but that would be untried and untested. We’re not the kind who’ll sit at home with two labradors and get married and have 2.2 children. We’re just not that sort of people.’ Although taken by surprise, they are quite certain that they intend to continue with their father’s work, but with some changes. However, his death deprived the business of unsurpassed technical expertise and tacit knowledge about the way the company operated and about its products. Nevertheless, they disagreed with his autocratic managerial style and his vision of the enterprise as a family concern and began to initiate some changes in management style. Justifying this they pointed to the flaws in his style: ‘I feel sorry for anybody who goes through the traumatic moment when they actually have to step into the shoes of the founder. I was on the board of directors since 1982. But I was still wet behind the ears because my father was the type of entrepreneur who controlled everything. I went to board meetings and was told by my father, “You don’t say a thing and you kick if I kick you”.’ This was a watershed for them both as they realised that his very distinctive managerial style had rendered them dependent on him for direction. They also realised that even if they wished it, combined they were not the reincarnation of their father’s embodied knowledge. As a result they made several changes, including a restructuring, the recruitment of senior managers, the initiation of a new multi-divisional product and marketing/sales policy, a change in management style and extensive capital investments. Attuned to the decline in the manufacturing sector the sisters brought about a policy shift with a restructuring and the closure of some of the international subsidiaries, accompanied by redundancies. They also initiated a new marketing strategy with five divisions, arguing that: ‘This means that the products compensate for each other. It has held us in good stead really.’ This contrasts with the stereotypical view espoused especially by the male entrepreneurs that women have no strategic view of the business or of financial management. 142 Class, Gender and the Family Business Their entrepreneurial sense is again conveyed in the manner in which they changed the management structure and style. Pointing to the key problem characterising succession they argue: ‘Well, things have changed a great deal since my father started out and this made a change of approach necessary. If you lose a head of the company like we did, you have no option but to delegate. In fact, the quality of the management that we have now brought in is far better than we had with the entrepreneur sitting at the top of the table who had his hands on everything.’ Whilst retaining a hierarchical structure, they have replaced the entrepreneurial head with new appointments in both the operational and strategic dimensions of the enterprise and have delegated some of the decision-making powers. The notion of the family business had considerable potency until ownership succession. Indeed, during the phase of wealth creation characteristically this business drew on extended family members. While this may have made good business, the women owners argued that the changing economic climate necessitated a shift from such paternalism. The family could no longer supply the range of skills necessary in the restructured enterprise. They also argued that the authoritarian patriarchal managerial style and the concentration of power in a single head was outdated and inappropriate in the new environment. Summing this up, they mused: ‘And I am not sure how my father would have fared in the current economic environment, being the true entrepreneur that he was. You couldn’t have found a more dedicated person. The trouble was, he couldn’t let go.’ Nevertheless, like their male counterparts, they appreciate that they have gained valuable skills from their father’s managerial style: ‘My father has given us a very good company and it is our duty now to develop the foundations that he created. It is a very different company now. We have invested £2 million on machinery. My father had a lot of reserves. Right now we are in a very strong position. We didn’t take any risk at all. I mean we’re now the most modern moulding shop in Europe. My father being the true entrepreneur saved and spent. He made a few big investments in property which turned out OK. Otherwise the money went back into the business.’ Women Owners: Honorary Men? 143 This example endorses the effectiveness of the apprenticeship model as a knowledge source for women owner-managers also. In this sense their approach to financial direction of the business is largely influenced by organic growth and careful investments. The fifth female business owner inherited a 500-year-old family estate in the mid-1980s. Out of a total of fifteen businesses in the landed sector, this is the only one that is female-owned. In the ‘old’ wealth category, it consists of a small holding of land, a country house, a title, a collection of paintings, valuable furniture and various new businesses that stem directly from the property. The present owner’s family bought the estate from Henry VIII in 1540 when the landholding was probably much greater. Interestingly, this family changed their religious affiliation three times over the centuries in order to gain political favours and to safeguard their wealthholding. The property has remained within the family through the male line and historically female kin have at various intervals inherited the property and have made considerable contributions towards its growth and preservation. For instance, the present owner’s great grandmother bought several of the paintings: ‘Yes, she bought what we call the Stuart Collection which is great asset.’ Clearly, this woman had considerable wealth and influence and bought the collection of paintings from the Pope. It seems that the ownership of the property changed to the female line through politically contrived marriages. However, this did not mean that it represented any challenge to primogeniture, rather the family women implemented this practice with the aim of enhancing the social status of their male kin, at the expense of the male members of their marriage family. The present owner’s father inherited the property in 1958 and, in the absence of male heirs, this witnessed the beginning of her apprenticeship for eventual ownership. Like other heirs she went to public school and then to university to read for a degree in art history. Meanwhile she was involved with her parents in the restoration and refurbishment of the house. Unlike her male counterparts this was not followed by a period of work experience in the City, because on completion of her education, she returned home and worked alongside her parents. In this sense the women are disadvantaged, for they are stereotypically portrayed as being poor at finance, which is essential in the management of such enterprise. This, of course, does not mean that such women make poor financial managers, but it makes marriage an inevitability if they are to assume formal ownership. The marriage then upholds the 144 Class, Gender and the Family Business notion of the family business with the inclusion of the male spouse in the management of the enterprise. Regardless of what configuration the actual sex division of labour takes, the effect is to endorse gender stereotyping, with the male as de facto head while the woman partner is the de jure owner. The woman’s role is perceived to be best articulated in some kind of creative project and as the interviews suggests this is intentional: ‘Well, I came home and worked with my parents. The restoration was an enormous task and in a business which this is, it has to be run as such. But of course, it was something that I had to do. I spent so much time working on the restoration.’ However, such women are equally concerned and knowledgeable about the strategic and financial direction of the business and with the creative input. This case suggests that women do both things. For instance, in addition to restoring the house, since the present owner inherited the business, she has developed lucrative corporate entertainment and the commercialisation of the parklands. Typically, and similar to her class peers, she has recognised that the considerable capital assets which they own do not generate income, except from the land. In turning over some of the accommodation for business purposes, she has been able to transform a fixed asset into a viable, income-generating project: ‘I mean, this has worked out very well. Only 20 per cent of our visitors ever come to the house. My idea was that we had all these quite beautiful rooms and they were very little used. So now we run a business that can be loosely described as corporate hospitality. This means a company will hire out the ballroom for a day, or a weekend and even maybe the park. They hold events in the park and organise parties in the ballroom. This is a very profitable dimension of our business.’ Other income is generated by opening the house and gardens to the public on a seasonal basis. The whole enterprise is managed by herself and her husband, who since his retirement from the army has worked full-time in the business. They employ a half dozen people on a fulltime basis and a fluctuating number of seasonal employees, and minimise labour costs by contracting out most of the farm work. But unquestioningly seeing herself as the driving force behind the direction of the enterprise raises some important questions about women and decision-making. Resembling male owners, this woman conveys a Women Owners: Honorary Men? 145 strong sense of ownership and assured sense of power and hierarchy, which is all the more surprising given that her husband works alongside her, but in a rather complementary and subordinate way. This example is illustrative of the manner in which the hierarchy underpinning gender relations can be overturned by the power of social class relations. Managing inheritance Female wealthholders are very similar to their male counterparts in the sense that their approach to business development closely emulates male strategies. For instance, the female business owners follow Penrose’s (1980) business model, where the primary intention is to create wealth based on the firm’s identity, brand and product. At the same time, as the example of the plastic manufacturing business shows, where necessary, women entrepreneurs also draw on market principles, such as the rationalisation of management style, in order to preserve the product and the business. There is a second sense in which women owners mirror the behaviour of their male counterparts and this refers to the question of inheritance. Three of the women owners had no children, but the cosmetics entrepreneur had a son and a daughter and the livery owner had a daughter. Like male owners they also intend to adopt the practice of primogeniture and give preference to male family members with regard to inheritance. For instance, the owner of the cosmetic firm, now aged 81, had already delegated the management of the enterprise to her son, but she intends to make him the majority shareholder within the family enterprise. Whilst the ownership is shared between herself, her son/manager and her daughter, it seems illogical not to pass on the business to her daughter for a numbers of reasons. The first is that her daughter was much more involved with the fashion design enterprise and the promotion of the company brand name. Of particular significance was her career as a fashion model, which provided a unique opportunity to promote her mother’s business. Fashion and pop celebrities frequented her retail outlets partly as a result of her daughter’s networking. She also explained that her daughter was often involved in some of the early experiments for the cosmetic business, making her a more likely candidate for eventual ownership. Moreover, her son had a separate career and appears to have taken little interest in the business. Second, given that Mrs M. considers that she has cast aside conventional social norms in the manner in which she challenged a male-dominated business 146 Class, Gender and the Family Business world and her apparent pro-feminist politics and managerial approach, this might suggest a rejection of conventional thinking on the question of succession and inheritance. Yet, in line with her class norms, Mrs M.’s daughter married an architect entrepreneur and is not involved in his business. However, Mrs M.’s has not totally relinquished her position as business head, and indeed by continuing to promote the business around her reputation as an entrepreneur, she greatly overshadows her son’s role as chief executive. Nevertheless, it seems that there was never any doubt about his inheritance: ‘R. always loved the countryside and, I mean, one of my reasons for moving to London was so that he could go to Harrow and be near home. I mean he always hated London and when I changed course I knew he would love the countryside. My daughter married K. and breeds Shetland ponies down in N. and, of course, R. is here with his family running the whole thing. And that is the way it should be as far as I’m concerned.’ Bourdieu’s notion of habitus helps to explain the apparent contradiction in Mrs’ M. decision. For instance, when she entered business in the 1930s she manipulated the dynamics of her gender identity with her social class resources to gain entry into the business world and in so doing the choices she made concerned only herself. However, the succession involves a wider set of social actors, her kin, when she drew comfort from social convention and passed the enterprise to her son. This has connotations of ‘doing the right thing’ in the context of dominant social values. The logic of such a decision can be explained in Bourdieu’s notion of habitus when social actors draw on internalised values that stem from their interaction, mediation and interpretation of convention in making sense of the social world. However, in reaffirming the alliance between capital and patriarchy, decisions such as this serve to perpetuate the current configuration in the social relations of production and the relationship between entrepreneurial men and capital, and between women, men and capital. The question of inheritance was not of immediate concern to the owner of the livery business. In describing her business as lifestyle she envisaged that she would continue working until, like many of her male contemporaries, circumstances forced her to give up. She has one daughter, aged 19, who is working towards a separate career away from the family enterprise. Nevertheless, the livery business has always been of pivotal importance to the daughter who was also encouraged to learn the business. Women Owners: Honorary Men? 147 ‘Right from when she was a little girl she has been with horses and had numerous ones of her own. I mean she worked as a stable girl and knows how to groom and so on. So, of course, if she wants to continue that is fine. But whether people will have the money any more is the big question. In the 1980s there was a lot of money floating about. Everyone bought a horse and wanted a slice of the country life. But that’s very much over now. And our local farmers are having a really bad time.’ Whilst this business is asset-rich, as part of the rural leisure industry its vitality is very much influenced by economic conditions. This point is exemplified in the change in the business cycle characteristic of this business. Whilst the conspicuous affluence of the 1980s generated more new business, the recession that followed in the 1990s witnessed the disappearance of such market expansion. The respondent’s pessimism stems also from the crisis in farming which, it is anticipated, will have negative repercussions for the business. By encouraging her daughter to train for an unrelated career, this entrepreneur is managing the crisis and safeguarding the business for the future. Emotionally attached to their businesses and, in this case, way of life, the desire on the part of founding entrepreneurs to see their businesses survive them is very strong, and the intention is that the daughter will inherit the business in due course. The desire to hand the business on to the next generation extends beyond the founding entrepreneur. The issue of inheritance poses some problems for the women owners of the plastics manufacturing and is rooted in the dilemma women face over the contradictions in attempting to strike a balance between the demands of home and work. Wajcman (1998) discovered that women in the corporate sector who succeeded to senior managerial roles had to forgo having children. Whether these two women will emulate this pattern is an open question. However, what this example yet again illuminates is the deepseated contradictions that powerful public sphere positions still pose for women. The two female owners of this company see themselves as professionals dedicated to the business, and they intend to grow it and to hand it on: ‘It is just not common sense in my opinion to think of selling something when it’s going well. I mean we don’t just look at the business as security just for us as a family. I look on it as something we can hand on in good shape.’ 148 Class, Gender and the Family Business As argued in earlier chapters the business and the family are intertwined in a number of ways. The family business as a source of wealth ensures security for kin and is tied up with status-building and social identity. Sharing their father’s values they seek to invest in the business and preserve it through inheritance, which in some ways guarantees a certain degree of immortality for the family name. But to do this they need to emulate patriarchal practices and have children, but this contravenes their notion of personal freedom and life choices: ‘We have a commitment to the business and we would like to see it thrive and survive and we are working towards that goal. No, we don’t see ourselves waiting at home. You know being the wife. We want to achieve out there in that world, which is what our father did.’ This comment shows that the women clearly understand that their primary duty is to sustain the business in its present form and are prepared to relinquish conventional childbearing and child-rearing roles in order to bring this ambition to fruition. By insisting that the business takes precedence, the comment demonstrates how problematic gender relations are for such women. The women feel compelled to distance themselves from domesticity, yet this confronts their longer-term duty to protect the business by passing it on to a suitable heir. By contrast, the class system has generated extended rules governing the perpetuation of wealth in the case of childless upper class female wealthholders. In the case of ‘old’ wealth very often the core wealthholding is held in trust, which means that an owner’s decisions are often circumscribed by rules of the trust, which is in any case skewed towards male ownership. ‘Well, the ownership thing is quite complex. This place was put in a trust in the very late nineteenth century. I don’t have any children, so after me this goes to a cousin. He is a cousin on two sides, which is nice. His mother was my father’s first cousin once removed, and his father was my father’s first cousin on the other side. He will eventually own this and if I die tomorrow my two female cousins are the joint heirs to the A. peerage, but as one has no children, and as my other cousin’s eldest son is going to inherit this place, he is likely to inherit the A. peerage also. He seems the ideal person. He is a Ghurka and is leaving at the end of the year. He is then going into the City and I guess will make some money. There is a cottage on the estate which will be his weekend base. He is beginning to take an interest. He is twenty-six years old. Can’t be bad, can it?’ Women Owners: Honorary Men? 149 This suggests that it is only in rather exceptional circumstances that female kin are able to inherit ‘old’ wealth within aristocratic family structures. It also seems that in this case the woman is a nominal owner as the property is held in trust and the only leverage she appears to have is over the title, which in this case is going to the heir of the core wealth. Undoubtedly, this practice is tribal in character for it excludes all but blood male kin. Of course, as Chapter 5 suggests, there are provisions made for female kin. However, these are gendered practices in that female kin are expected to marry and thereafter are dependent on their husbands. The limited evidence of the safeguarding of a wife’s interests through pre-nuptial agreements suggests that in some families consideration is given to the possibility of failure. Nevertheless, as this example shows, women with powers of decision-making give primacy to their class identity and adopt conventional practice. Having internalised the dominant values characteristic of their social class typically they argue: ‘I think it is important for various reasons. One of them is that this is a beautiful house, and the fact that it has been with the family for 500 years, one does not want to be the one who is going to throw in the sponge. It is tremendously important to preserve the thing and hand it on in a little better condition than you found it. The only thing I ever sold was a picture I didn’t like. It was one of William of Orange being triumphant at the Battle of the Boyne.’ This sentiment, emphasising the importance of duty and of sustaining and safeguarding the family wealth, suggests that when women occupy the position of wealthholder they are reluctant to challenge convention. There is a sense in which this comment is consonant with research reported by Rosener (1990) which suggests that the first wave of female executives adopted male managerial styles. Conclusions In focusing on the five women proprietors this chapter has argued that they differ very little from their male counterparts in their approach to business formation, and the management and preservation of their enterprise. Like their male counterparts, the first-generation wealthholders began their businesses advantaged by the resources associated with their social class. In one case, the livery entrepreneur had been able to transform her hobby, an interest in breeding and training horses, into a viable enterprise. In the second, like many of her male counter- 150 Class, Gender and the Family Business parts, the fashion and cosmetic entrepreneur utilised her employment experience as a designer as the preamble to her own enterprise. With regard to finance, it is clear that the fashion entrepreneur and the lively entrepreneur had been able to draw on some family money to develop what had been interests and expertise on a business footing. Like the male entrepreneurs, they negotiated the support of their spouses, and therefore seem to have overturned the conventions characterising gender relations. In looking at the inherited businesses it is clear that, like their male entrepreneurs, the women owners underwent a business apprenticeship prior to their inheritance, and thereafter adopted the conventional approach on the issue of inheritance, indicating that they will pass their wealth on via the male line. Whether such women are ‘honorary men’ is an open question, because it seems that their business success lies in the peculiarity of a shared management strategy. On the other hand, the importance of this strategy is that it prevents the disintegration of the core productive wealth, whilst it also sustains the social class position of the families concerned. What this implies is that both men and women occupy ‘places’, that result in the survival of the enterprise and social status of the family. 9 The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies This chapter argues that the preservation of family enterprise hinges on a family business strategy that places its key emphasis on leadership training and particular inheritance practices. It also questions the convention of studying majority and ethnic minority business separately and argues that it is difference that is exaggerated. This creates the impression that each business category is engaged in discrete economic activities, driven in very different ways, producing different types of goods and services for different markets. There is also a silence about the class roots, the ethnicity and the gendered character of majority business. On the other hand, gender and class identities, and the dynamics of this relationship, are completely overshadowed by the elevation of ethnicity in studies on ethnic minority entrepreneurship. For instance, Werbner (1984), who is a very influential writer, thinks that ethnicity is the primary driving force behind ethnic minority enterprise. Typically, this work also assumes that the utilisation of kinship relations as a business resource is unique to ethnic minority enterprise. The result is that the importance of the class identity of ethnic minority business leaders and the significance that social class relations has for such enterprise is lost in discourses that exclusively address kinship relations and ethnicity. Such silences and myopia result in a failure to identify that ethnic identities are shaped by the power of class/gender systems in family capitalism. This chapter addresses this question showing that social class identities are important when considering enterprise. This chapter also questions Bonacich and Modell’s (1980) notion of middleman1 theory and Aldrich’s (1980) enclave2 theory, both of which argue that ethnic minority business cannot be seen as a key player in the economy. They argue that such businesses are forced by circumstance into less vibrant and marginal economic sectors where returns 151 152 Class, Gender and the Family Business are low. Undoubtedly, this argument has some validity, but the problem is that it paints a rather static image of such business, for it cannot be assumed that every ethnic entrepreneur enters a peripheral sector and then remains there. Finally, in exploring these questions, this chapter demonstrates that the family business is largely driven by and is dependent upon a shared business culture. It is argued that this culture stems from a similarity in the class background of the actors concerned, a shared value system and common business strategies, which transcend but does not subsume ethnicity, while reinstating the patriarchal family as the key agent in the generation of family capitalism. The notion of shared business culture The argument about similarity is embodied in the notion of a shared business culture and emerges from the practice of creating, managing and sustaining family enterprise. The idea of a business culture refers to particular practices with reference to managing and financing the business. The first aspect of this culture is a concern with business leadership, approaches to succession, the production of specific human capital and entrepreneurial expertise. Equally important is the second aspect, when there is preference for the private sourcing of investment capital, riskavoidance in relation to business growth, a reliance on family labour and the nurturing and utilisation of social capital (Boissevain, 1974) or structural holes (Burt, 1992). In this context, the structure comprises instrumentally determined social networks of friends which duly provide assistance in the pursuit of business goals. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that there are differences between ethnic minority and white majority enterprise. It is, of course, important to acknowledge that differences exist between the business groups. For instance, racial discrimination, access to cheap ethnic minority labour and an entrepreneurial reputation distinguish ethnic minority businesses from their white majority counterparts. However, it will be argued that the structural position of ethnic minority business is more complex than the peripheral account offered by enclave (Werbner, 1990) and middleman theories (Bonacich and Modell, 1980). It will be demonstrated that such businesses are in a transitional phase, are making inroads into most economic sectors, and provide goods and services to the wider society. Theoretically, Bourdieu’s (1976) notion of habitus and Roberts and Holyroyd’s (1992: 159) definition of substantive rationality will be drawn on to make sense of the notion shared business culture. First, habitus at The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 153 the level of culture can be understood as a particular form of class strategy. Habitus as culture conveys a sense of best practice, or way of doing things, that is unconsciously internalised, and as a practice is unquestioned. For instance, patterns of female exclusion, and the manner in which gender difference influences leadership and training, are regarded as common sense by family decision-makers, because they see it as a way of producing effective managers and future heirs for the businesses. The preservation of such business wealth, the male line and the wider family status and identity are powerful endorsements that such action is rational, meaningful, legitimate and purposeful. The notion of habitus serving as a class strategy is embedded in, and is an elaboration of, culture as the reproduction of patterns of rational socio-economic behaviour over time. This argument is transparent in respect of business succession, when the practice of seeking business leaders within the family seems contrary to market values. The validity of Robert and Holyroyd’s (1992) notion of substantive rationality is borne out, because it places in context why particularistic values, a legacy from kinship systems and an earlier form of class society have a rationality of their own, which can be compatible with modern rationality, in that calculation underlines kinship relations in order to further the business. Theoretical perspectives and perceptions of minority business It is necessary to locate this argument within the ongoing debates about the processes of business formation, and also to say something about the way in which the literature is organised. The segregated presentation of business formation arises out of particular traditions and interests. For instance, the study of ethnic minority entrepreneurship has been confined to academic disciplines dealing with questions of social concern such as migration, race and ethnicity. Theoretically, this constitutes a large body of literature which can be divided into three main approaches, the materialist structuralist (Anwar, 1979; Aldrich, 1980; Bonacich and Modell, 1980; Hoel, 1982; Aldrich et al., 1984; Morokvasic, 1987; Phizacklea, 1988; Morokvasic et al., 1990; Scully, 1994); the interactionist approach (Waldinger, 1984; Bun and Hui, 1995); and the cultural approach (Boissevain, 1990; Clark, Peach and Vertovec, 1990; Werbner, 1990). The first two begin from a demand-side perspective and focus on the material constraints and the limited opportunities open to working-class minority entrepreneurs, arguing that it is blocked opportunities through racial discrimination (Phizacklea, 1990; 154 Class, Gender and the Family Business Bun and Hui, 1995) as opposed to the specificity of ethnic minority culture (Werbner, 1990) that act as the push factor in the rise of minority ethnic entrepreneurship. This evaluation reveals that the claimed advantages associated with ethnicity are undoubtedly double-edged. Although such entrepreneurs find within their own communities more favourable terms in the sourcing of capital, labour and markets for their goods and services, the socio-economic costs are also borne within their own communities, some of which in gender terms. For instance, Phizacklea (1990) and Morokvasic (1987) argue that so-called ethnic advantage means that unpaid female family members work long hours running small enterprises in marginal markets. This literature clearly shows that rates of entrepreneurial activity are not synonymous with business strength, for such enterprise is predominantly an alternative to unemployment, is small-scale and structurally peripheral, remaining vibrant only through cost-cutting strategies (Phizacklea, 1990). The structural expression of this is the enclave economy particularly evident in the small retail outlets serving only ethnic minority and working-class communities. Ram’s (1994) ethnographic study of the clothing industry and his description of ethnic minority enterprise as a series of coping strategies show the wider significance of this model. Other very influential writers, such as Aldrich et al. (1984), suggest that this model remains the reality for the majority of working-class minority entrepreneurs, suggesting that enterprise does not produce the upward mobility so vigorously espoused by advocates of the enterprise culture. The cultural approach is essentially a supply-side explanation and ignores social class relations and equally takes for granted the enabling effect of social class attributes (Werbner, 1984; Clark, Peach and Vetrovec, 1990; Rubeinstein, 1990). This is a very important point in respect of this study for most of the ethnic minority entrepreneurs as well as their white majority counterparts are middle-class and are advantaged relative to their co-minority ethnic counterparts. At the heart of the cultural approach is the notion that particular cultural (ethnic) attributes such as a group’s beliefs, values and resources have the empowering effect of being able to transform social disadvantage into material advantage, suggesting that their distinctiveness and essence lies in the specificity of ethnicity. Accordingly, the particular belief system is predisposed towards enterprise which embodies a set of interacting principles, such as the moral good of self-reliance, discipline, the rigours of hard work, frugality and wealth accumulation. More seriously, the primacy given to ethnicity leads to, or reproduces, racial stereotyping The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 155 and the notion of flawed cultures (Rubeinstein, 1990; Peach, quoted in The Independent, 12 June 1996), when one set of values is privileged over another (Lessnoff, 1994). For instance, Peach’s (1996) work draws a distinction between a perception of the entrepreneurial, resourceful and upwardly mobile Anglo-Jews and Asians and the allegedly less enterprising Afro-Caribbeans and Irish. This thinking lends itself to the notion of a hierarchy of cultures and the reinvigoration of the negative racial stereotyping of some groups (The Independent, 21 June 1996: 3). Conveniently, it shifts attention away from the opportunity structure and the importance of class relations and class identity. It is at this point that cultural explanations coincide with the birth of neoliberalism during the 1980s when policy-makers and politicians promoted the notion of the enterprise culture (Keat and Abercrombie, 1991). There are variants of this discourse, which indicates that the neoliberal message is selective and has reached white entrepreneurs and Asian communities only. In the first instance, the biographic literature (Lynn, 1974; Kennedy, 1980) recounts stories of ‘rags to riches’ business success, a claim which has been repudiated by Davidoff and Hall (1987) and Mulholland (1996a, 1996b). In the case of the Asian communities, their entrepreneurial reputation has been promoted by Conservative politicians and the broadsheet newspapers. For instance, stories of the rising number of Asian millionaires appeared in the Daily Telegraph (21 August 1984), Management Today (1990) and The Independent (12 June 1996). These and similar accounts portray an image of Asian business as high-powered and glamorous, another variant of ‘the rags to riches’ theme. On the one hand, these accounts enhance the Asian entrepreneurial reputation, while, on the other hand, it greatly exaggerates the strength of most ethnic minority businesses. Both strands of literature make similar claims about the merits of enterprise in that they promote what can be described as the workingclass entrepreneurial model: disadvantaged groups such as working-class people and migrant labourers, provided they choose business, can be transformed into international business magnates. In a tacit way it fuels what Ward and Jenkins (1984) might describe as a blame culture because it implies that poverty and racism can be cordoned off as supply-side problems. The achievements of the working-class entrepreneurial model is overstated, because a few businesses correspond to this model. The present study failed to identify any redundant coalminers or former factory workers-turned-successful business people. For the most part, the busi- 156 Class, Gender and the Family Business ness families were middle-class in terms of their family background, formal education, training and former occupation. Nevertheless, it is important to recognise that in exceptional cases the labouring entrepreneurial model and the working-class entrepreneurial counterpart has a certain validity, when individuals succeed in intra-generational mobility through enterprise. In the American context, Bun and Hui (1995) and Bonacich (1988) lend some support to this view. Two entrepreneurial models are identified, the first and dominant one is the middle-class entrepreneurial model which includes most white majority businesses and in the case of the minority business refers to the Asian businesses of East African origin and Anglo-Jewish businesses. The second model, the migrant labouring/working-class model, refers to incomers from India and Ireland and entrepreneurs from a workingclass background. Members of these groups are very different because they lack the business background and education characterising their middle-class counterparts and spend many years working as labourers prior to business start-up. Questions of ethnicity In order to examine these arguments it is important to comment on the ethnic identities of the 70 businesses whilst taking account of the age of the enterprise and their location in the economy. It was shown earlier that 26 of the businesses were inherited and managed by secondgeneration owners, whilst 44 businesses were newly established, or firstgeneration businesses. Showing that there are fewer inherited businesses raises interesting questions about the character of managerial strategies and why some families managed to preserve their business through different generations of ownership. In turning to the question of the ethnic identity of the business owners, 52 are white majority owners and 18 are members of ethnic minority groups. It should be noted that one of the primary aims of the study was to convey some sense of the way ‘millionaire business families’ managed their wealth, and this led to a bias in the ethnic composition of the sample. The 18 minority ethnic businesses consist of one Irish, three AngloJewish, three Indian origin and eleven East African Asian origin. The over-representation of East African businesses needs some comment. They are a very distinctive group in that they have a very different migration pattern. When they first migrated to East Africa they occupied a middle position in the economy as traders and merchants (Clark, Peach and Vertovec, 1990; Twaddle, 1990) before setting up in business The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 157 in the 1970s and 1980s in Britain. They were educated in the tradition of the British system, spoke fluent English and had established links with the United Kingdom. The issue of the generational phase of the businesses is blurred, because they had owned business in Kenya and Uganda until they became victims of abrupt mass deportations. Others were students in Britain and later set up businesses. Although they were placed in unenviable circumstances, they were essentially aspiring middle-class business people looking for entrepreneurial opportunities as opposed to employment. Another factor explaining their overrepresentation relates to the manner in which they settled in cities in the Midlands and in the North, where they were able to obtain labour at more competitive prices. The other attraction of these regions is that they had small and medium-sized businesses in textiles and knitting that were available to incoming entrepreneurs. It was often these restructured business that were sold to the incomers. Ethnicities and market position Table 9.1 shows the spread of the business categories across different economic sectors. Distribution is fairly even, except that over half of Table 9.1 Distribution of ethnic minority and white majority ‘new’ and ‘old’ businesses Business sector ‘New’ Ethnic Minority Businesses ‘New’ White Majority Businesses Old’ White Businesses Total – 6 15 21 1 – 1 5 1 3 3 8 Land Civil Engineering, Quarries & Construction Manufacturing Textiles (non-specific) Property Finance Food & Drink Service Sector (non-specific) Diversified 2 1 3 – 2 1 – – 1 1 – 2 5 3 3 2 1 10 7 4 2 1 10 15 Totals 18 26 26 70 158 Class, Gender and the Family Business the inherited businesses are in land, and proportionately more of the ‘new’ business are diversified and have investments in more that one economic sector. First, the concentration of the ‘old’ businesses in land is an important finding, for it identifies one of the key strategies in which wealtholding is preserved across generations. Interestingly, as Table 9.2 indicates, there is a tendency amongst the ‘new’ business, and particularly for the ethnic minority enterprises, to buy into property while white businesses have made considerable investments in land, simultaneously running businesses in different sectors. The logic of the spreading of business assets is explained by Wedgewood (1929), who argues that, following land, property is the second most stable capital investment. However, diversification can also be accounted for in patterns of economic restructuring. Anwar (1979) observes that newcomers often enter declining sectors where there is less competition and entry requirements are lower. For instance, the Asians in some of the northern cities entered the jewellery business vacated by increasingly socially mobile Anglo-Jews. A similar pattern has been observed for this study when ethnic minority business at point of entry went into retail, textiles and the clothing industries. This has an opportunistic aspect for it is regarded as a temporary measure while planning and seeking better business ventures, but it is important to locate this trend within the wider precursors of business entry. Business start-up and entrepreneurial models The precursors to business entry for both entrepreneurial models and majority and minority categories are the same. These include low entry requirements, low capital investment privately sourced, low-level technology, a background in business, high educational attainment, business expertise or knowledge of the entry sector at start-up either through work experience or professional training and access to family labour. The next example discusses how an East African business family overcame the limitations of entry into the depressed retail sector. They used a combination of resources – for instance, market awareness, the use of social (Boissevain, 1974; Burt, 1992) and ethnic (Werbner, 1984) networks, cautious financing, opportunism and skilled family labour – in the build-up of a medium-sized international exporting business: ‘We were Ugandan refugees and we came in 1972 when I was seven. My father had businesses there, several petrol stations and other trading businesses, which was quite similar to what we are doing now. But we had to Date of entry 1968 1964 1979 1970s 1972 1970s 1971 1977 1974 1972 Business number E1 (Indian origin) E2 (Indian origin) E3 (Anglo-Jewish) E4 (Anglo-Jewish) E6 (East African origin) E9 (East African origin) E11 (East African origin) E12 (East African origin) E13 (East African origin) E14 (East African origin) Manufacture of clothing Grocery/Car dealership/Knitwear manufacturer Partnership in accountancy Supermarket/Cinema Printing Manufacture Tie manufacturer Tie manufacturing Market stall Clothing manufacture Start-up business Table 9.2 Diversified business among ethnic minority and majority categories Accountancy and hotels Estate agency/Insurance/Travel property Hairdressing/Property Manufacture/Property development/ Manages overseas portfolio for family International business/Exports pharmaceuticals and textiles Wholesale/Export/Property development Wholesale/Export/Property development Tie manufacturing/Property development Art gallery/Property development/Bookshops Fabric dyeing/Export Business shift The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 159 1954 1952 1970s 1979 1960s 1960s E16 (Indian origin) E18 (Irish origin) NI.23 NI 24 NI.25 NI.26 E refers to ethnic. NI refers to ‘new’ ‘non-ethnic’. OI refers to ‘old’ ‘non-ethnic’. Total = 17 OI.16 Date of entry Business number Table 9.2 Continued Estate Restaurant Food manufacture Property Self-employed building trade Landlord Self-employed plant hire Start-up business Estate agency/Property development Plant maintenance/ International client/Open cast mining/Land for exploration Speculative building/Motor cycle manufacture/Estate farming Advertising/Employment agencies/ Asset-stripping/Playing stock market/ Property Food manufacture/ Estate farming Restaurant chain/Farming and civil engineering businesses in USA/Niche hotel Estate/Stockbroking Business shift 160 Class, Gender and the Family Business The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 161 leave that. The first thing he did was to operate a market stall selling shoes. He wanted to do something on his own. Off his own back, yes. He then found a partner and they gradually built the business to seven or eight shops. He later bought his partner out and gradually built up his small empire. My father was always the father figure, because my grandfather died young, and he had to take on the responsibility for his five brothers studying here, some were at university, and others were doing accountancy and so on.’ The next step was to relocate the family and business from London to the Midlands where the cost of labour was more competitive and co-ethnic labour was available. The retail businesses were sold and the capital reinvested in a former hosiery plant for the manufacture of fashion clothing, initially supplying the domestic market. It is the character of the next move that separates this entrepreneur from ethnic minority migrant and white working-class counterparts: ‘My father then with a colleague set up another factory in Nigeria, which was booming at the time. The reason my father chose Africa is he has got it in his blood all the time. He can work with the people there, he understands them. He was interested in trading and saw an opportunity there. There was a market there also for industrial machinery, petro-chemicals, pharmaceuticals, computers, and so on.’ In this example the importance of experience and background cannot be overstated, for this entrepreneur drew on international business connections and business skills to develop the business into an export concern. Yet the family argue that this move into new commodities and new markets is an extension of the earlier business, which indicates the sense in which continuity is regarded as important. It could also be argued at a substantive level that knowledge about business processes influenced the direction of this enterprise: ‘Really, we have not changed since my grandfather began the company. We were then a trading company and we are now a trading company, but we have many international clients. We are interested in buying and selling, in sourcing a good product at a reasonable price and then selling it on to a client with a good commission.’ The expansion of the business coincided with the incorporation of the founder’s five siblings into the business: ‘As my uncles finished their 162 Class, Gender and the Family Business education they began to join the business.’ At the time of interview this family had established two branches in Nigeria, two in East Africa, one in Hong Kong and a branch in Dubai. The business was run by two generations of the same family, and each of the six brothers had responsibility for a branch of the business, while the local businesses were managed by a combination of recruited professionals and the son of the founding member. The founding member was chief executive and chair of the entire enterprise. In terms of the source of capital for this business, characteristically the phase of restart required very little money, and the family claim to have had no reserves and typically argue that growth is organic, supplemented by family labour and short-term borrowing within the business community. Employing several male siblings in the management of the business is consistent with the management practices characteristic of industrial family capitalism, providing career paths, while also safeguarding against labour market discrimination. Middle-class ethnic minority entrepreneurs are reluctant to admit that the family business shields them from labour market discrimination, but this is implicitly acknowledged in the ethos of paternalism characteristic of family capitalism: ‘My father was interested in building something for us as a family, to be independent and to provide for us. To that goal he committed himself 100 per cent.’ What seems important in explaining the growth of this particular business is knowledge of markets combined with business connections and entrepreneurial expertise. Arguably, what differentiates this example has been the range and quality of enabling resources, which are middle-class attributes such as the former business background, business expertise, business connections aligned with market awareness and the strategic incorporation of well-educated male family members into the enterprise. The overall point is that this case is not representative of the Asian business community for, as Phizacklea (1990) would argue, most of those entering marginal sectors remain there. As a departure from the migrant labouring model, this is one version of the middleclass entrepreneurial model discussed by Bonacich (1988) and Bun and Hui (1995). Similarly, the following are examples of white majority and other ethnic minority entrepreneurs whose businesses reflect the low entry requirement, but nevertheless who have succeeded in building up sub- The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 163 stantial businesses. However, what seems to be the key to their progress is the expertise of the business heads and their connections. These strengths are very often gained through the accountancy profession, which are then used as the spring-board to business. In discussing two such examples similarities and differences are explored. In the case of an East African entrepreneur an accountancy business acted as the foundation from which to reinvest into upmarket hotels and property. Mirroring the typical start-up profile, this entrepreneur was motivated by the lack of prospects as an employee and became a self-employed accountant. A business of this sort needed only a nominal capital outlay, the crucial issue at this stage being access to clients whom he was able to poach from his former employer, while also developing a client base from within the nascent Asian business community: ‘My father was in a managerial position with the M. Group who owned sugar plantations, glass factories, that sort of thing. My elder brother is in business in Kenya and I was sent off to England to study accountancy. In 1973 I had just trained as a Chartered Accountant, and because of the difficult political situation back in Kenya I saw no possibility of going back. I joined a local firm, where, whilst I was working reasonably hard, I didn’t see any prospect of a partnership or a reward for hard work. So I decided to start out on my own.’ Business growth was initially limited through restrictions on advertising and in having to rely largely on small jobs from minority co-ethnic clients. After building up a client base over a period of five years, the next step was to relocate to prestigious high street premises among the white majority business sector. Although this opened the business to the white client market, which now accounts for about a quarter of the income, and while the aim was to increase this market share, it was also to maintain the Asian clients: ‘Well, you see our East African clients are as important as ever, because over the years they have grown considerably and we have grown with them.’ This poses a challenge to cultural explanation of the enclave (Werbner, 1990), which suggests that the periphery reproduces itself over time and indicates some degree of organic growth and business interaction well beyond ethnic boundaries. In 1980 this entrepreneur took the decisive step of taking on a partner with a view to making investments in the property market, because accountancy was also seen to have limitations: 164 Class, Gender and the Family Business ‘Well, you see, while accountancy is a good business and is a good training in knowing about money and finance, but it is too time-oriented. You charge for the time you spend on a job, and I wanted to do something more. So around 1980 I started looking for investment property, hotels, that sort of thing. I bought a number of hotels, brought my brother in on the business, refurbished the hotels and gave them a corporate identity. One of my brothers is Operations Director.’ Nevertheless the advantage of running a professional business of this kind is that it is a learning environment which provides the opportunity to evaluate business strategies, and offers a unique insight into possible markets. Such knowledge helped to identify and assess the potential of such a venture which required considerable capital investment. This was raised through a variety of sources (organic growth in the other business, within the family, business colleagues and the banks), which again demonstrates the resourcefulness of such middle class families. This entrepreneur was also able to tap into family capital and expertise when another brother, a hotelier, was able to make a substantial investment: ‘My brother, who had come a bit later on to this country, had quite a bit of capital of his own and he had his own businesses here in hotels and property, so he provided some capital, and a few other friends, so they are shareholders.’ The argument that Asians are finding it easier to raise business capital through the banks is borne out with some qualification in the following comment: ‘Because of my professional background, I have got contacts with all the major clearing banks, and, you know, other banks coming into the area. I think if I wasn’t a professional man then, yes, I probably would have found it a bit more difficult in raising finance. Our policy is to keep gearing low and to conserve and invest. And of course, because of what we wanted to achieve we did borrow, but carefully.’ This is important and shows the significance of social class attributes, and is a convincing example of the influence of professional status. Contrary to the cultural analysis, this comment illustrates the ways in which business networks built around social class identity transcend ethnic boundaries. While there is considerable debate among writers The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 165 about the availability of finance capital for the small and the ethnic minority business sector, what has become clear from this study is that when migrant labouring entrepreneurs first attempted to secure startup capital from the banks they were refused. However, once they established their businesses and they had proved themselves, they were welcomed as banking customers. Nevertheless, though family capitalists are not averse to borrowing in the formal sector, there is a tendency to want to keep it to a minimum, the logic of which seems to be to avoid undue dependence on the banking institutions. Similarly it was professional training in accountancy alongside work experience in a manufacturing company that led a white majority entrepreneur to establish an international, medium-sized multi-plant manufacturing company in adhesives with sales and distribution branches in France, Germany and Holland: ‘My business started back in 1964 with two of my colleagues. We worked for a company which was principally engaged in making surgical selfadhesive applications. We realised that there was more of a market in the commercial adhesive tape field than in surgical plaster. And we were thinking of taking the plunge, and going for that on our own. Then things were rather precipitated because suddenly our company was taken over and moved away from the area. I had a financial background and was a trained cost accountant and we decided at that point to have a go at making commercial tapes ourselves.’ The characteristic pattern – a professional background, experience in the production processes and knowledge of the market environment – shows the consistency between professional paid employment and enterprise. Consistent with their ethnic minority counterparts, it was increasingly towards the family that this entrepreneur looked for investment capital: ‘We had very little money to start with. We had a few hundred pounds, and we raised around the same amount from parents and the in-laws. We are not talking of big sums. And of course, the banks. But we didn’t need a lot.’ With this money they found a plant, bought some of their former employer’s machinery and began production on a very small scale. This business, like the others, conforms to the low entry requirement and is characteristically low-level technology, but what seems crucial is the 166 Class, Gender and the Family Business reliance on different kinds of expertise shared between this entrepreneur and his partners, which was a mix of costing competencies, knowledge of markets and production processes. Like the ethnic minority counterparts, this entrepreneur emphasises product development, market expansion, organic growth and short-term borrowing: ‘We expanded only incrementally with our sales as the driving force and we did this principally by concentrating on a fairly narrow sector of the business and putting an emphasis on the quality of the product and managing it as effectively as possible. We financed this by simply ploughing our profits that we made back into the company and by using our normal bank overdraft.’ Over a period of twenty years this business bought three plants, two for production on green-field sites and one for distribution, while also establishing overseas sales and distribution units. This whole approach is risk-averse, the logic of which is to ensure internal entrepreneurial control over the financial direction of the business whilst accommodating rationally influenced kinship interests: ‘Our sons, my son and my colleague’s son, have now joined us. It was always on the cards. They joined us in their late twenties, they already have work experience, professional qualifications and degrees. The aim was to accommodate them, and we have. For instance, take my son. He is now running the French company. He is a French speaker. Likewise, my colleague’s son got a degree, joined ICI computers as a graduate trainee, was actually running their service support operation. We have now appointed him and he is responsible for the materials acquisition. Our hope is they eventually take over and take the company forward. We are looking to keep the business independent; we think the prospects for the company are better served that way. We employ over 300 people and, of course, we have a responsibility to them. We spend quite a lot of time thinking about where the company is going. We are a bit different in that we are probably the only independent company in the trade of any size with our turnover as opposed to ones that are part of a larger group.’ This comment is illustrative of the views of both majority and ethnic minority founding entrepreneurs and resonates of Penrose’s (1980) notion of the company man, illustrated in Chapter 6. Company identity is based on the reputation of the product, which is also embedded in The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 167 family identity. At the same time, the belief is that the business should be preserved in its present form because it accommodates a constellation of interests, serving the market, creating a surplus whilst addressing kinship interests which means the incorporation of the entrepreneurs’ sons. As the earlier chapters have shown, the arbitrary character of gender exclusion becomes transparent when the event of business foundation and growth is linked to the distribution of senior managerial positions and business inheritance. For instance, in over half the ‘new’ white majority and ethnic minority businesses, wives were invisible business partners and were denied formal recognition (Mulholland, 1996a). Wives in both categories contributed in a variety of ways, by working directly in the business in a wide range of tasks (which were rarely credited) and through financial investment. In some cases their marriages led their husbands to expand and upgrade their businesses considerably. In essence, they provide core resources to the business partnership (Mulholland, 1996a). While supporting Hoel (1982), Morokvasic (1987) and Phizacklea (1990), who argue for the centrality women’s labour in textiles and clothing-related businesses, with women providing key components of the labour process, such as technical skill and managerial competencies, this study offers evidence suggesting that this model of women’s and wifely contributions can be extended to a far wider range of business sectors (see also Phizacklea and Ram, 1996). However, paradoxically, the centrality of female kin as business partners runs parallel with their marginalisation in favour of male kin. For instance, as earlier chapters suggest, when male heirs are ready to assume their places in the ‘new’ business this can often be at the wife’s expense – she steps down as invisible manager or director and partner, and the son steps in as highly visible and much enhanced de jure partner to his father/owner/chief executive and as heir-in-waiting to complete the last phase of the apprenticeship training. Ethnicities and human capital, cultural or class practices The first key feature of a shared business strategy for both ethnic minority and majority categories, which involves the family in the production and the reproduction of a particular form of human capital, is the emphasis on formal education. This is to ensure that there is an elite 168 Class, Gender and the Family Business pool from which to select suitable heirs and managers for the family business. Marceau (1989) observes the same trend amongst European business families. The business families share a strong belief in the value of education, and like the majority families, those originating from East Africa received an education based on the British model. There are, of course, some important differences – some of the white majority and Anglo-Jewish entrepreneurs attended top public schools. On the other hand, some of the ethnic minority entrepreneurs were educated in the independent sector and intend to educate their own children there. Moreover, the East African Asians in particular made considerable financial investment and sent their children to England to study in the independent school sector, followed by professional training in accountancy or university. As part of their training, some joined large companies seeking experience before joining the family business. Two of the three Anglo-Jewish entrepreneurs attended a top public school or an independent school. The belief in education is again demonstrated by the fact that as many ethnic minority heads possessed qualifications as did their white majority counterparts. For instance, twelve (66 per cent) of the minority ethnic business heads as opposed to 61 per cent of the white majority business heads had an academic qualification. In terms of achievement, three of the ethnic minority heads had a degree, two had ‘A’ levels, one had eight ‘O’ levels and three were chartered accountants. By contrast there was a higher incidence of public and independent school attendance among the majority business heads, and twelve were educated at independent or top public schools. Given that private education is more valued, some white majority business heads were relatively advantaged and possessed a ‘desirable’ class identity which constituted a form of social capital not afforded to their ethnic counterparts (with the exceptions of the Anglo-Jewish heads), an advantage which often led to business opportunities closed to their working-class and migrant ethnic minority counterparts. Additionally, 61 per cent (16) of the white majority business leaders were formally qualified. Six had a degree, one of whom also had an MBA, three others were educated to ‘A’ levels and one had eight ‘O’ levels. Two were accountants, others were RAF officers, and three were craft-trained. The high incidence of educational attainment was part of a wider socialisation and wealth accumulation strategy, often constituting the first stage of a type of male apprenticeship and preparation for leadership and part of patriarchal exclusionary practices which circumscribed the kinds of roles and positions female kin could play in the business. The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 169 Succession and leadership training ‘The silverspoon syndrome’ The notion of the shared business strategy includes a long preparation which can be described as a gendered male apprenticeship which is focused, selective and geared to business management, but which excludes family women. This is essentially a male career path, in that all the business heads, regardless of ethnicity or phase of business development, experience a very similar trajectory. This results in the sharing of a strong belief in the inculcation of particular values and achieving high standards of education appropriate to business management. For instance the chairperson of a majority, fifth-generation, brewing company explained: ‘I was sent to Eton, this was followed by the Guards, the shop floor and then joining the brewery. After Sandhurst and a year in the City it was important that I was brought down to earth, so I joined another brewing house as a trainee on the retailing side.’ A newly appointed ethnic minority director of a design and dyeing export ‘new’ business followed a broadly similar career path: ‘I got a BSC in management science from Bradford University. This gave me a very good view of the marketing and the financial side of the business. I then did a short course to learn about the technical aspects of the dyeing business. When I left university I though it is a good idea to go and see how other industries are run, so I joined the insurance industry purely to learn something about sales techniques.’ Another ethnic minority respondent and heir to the international export ‘new’ business traces a familiar pattern: ‘I got good “A” Levels and went up to the LSE and got a degree in economics and management science. I was quite interested in the Stock Exchange and the stock market, and I did the various examinations for the Securities Association. My intention was to try and get some outside experience and bring something new into the company, possibly some new ideas of what is happening in the City, and ideas about finance and see how we could use it here.’ 170 Class, Gender and the Family Business This very entrenched practice with some modification also applies to working class migrant business families. The heir to a civil engineering ‘new’ business explains: ‘My Dad believed in education, and as the eldest child there was a lot of pressure on me. I went to . . . a public school, and did fairly well there academically, as did my other brothers. My father was keen for me to join him, but my mother persuaded him that I should be allowed to go to university. I then studied civil engineering . . . It was an opportunity to delay coming into the company. As the eldest son, I knew that was expected of me.’ While this educational regime is intended to imbue essential social and technical skills, character-building forms another aspect of it. This requires prospective heads to show that they deserve their privileged status, and that they appreciate and value the businesses they are to inherit and manage. It is a means by which to counteract ‘the silver spoon syndrome’. When they join the family business, their first jobs are lowstatus and unpleasant. This is part of the training and socialisation process and is a reminder of the importance of sobriety and possible bad times ahead in the case of poor leadership. The link between sobriety, responsibility and business as the symbol of achievement is a value which is shared by all the business heads. The chair of the ‘old’ brewing business explained: ‘Part of that involved working as a barman in one of the toughest pubs in S. For a start, it helped me to get to know our business and to also appreciate what I have been given. I became chair at the age of thirty-three, and I own most of the shares, well 90 per cent, so I have the power if I wanted to sell up everything tomorrow and not work another day. But my first duty is to further grow the value of this family business and to pass it on in better condition to the next generation. This can only be through business growth and not just profit.’ Typically, this example is illustrative of the manner in which the heirs of inherited businesses beneficiaries draw on the less pleasant aspects of their apprenticeship in order to rationalise their privileged positions. Similarly, the 27-year-old director and sole heir of the ‘new’ design and dyeing company points out: ‘I worked in the warehouse and on the dyeing machines on the shop floor. That’s where I started in the company. This was to remind me where my The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 171 family started. It is only over the last year that my father has made me a director. My objective is to build wealth. My father looked out for opportunities, I have to build on that. I’m in the business because I chose to join. On the other hand, I’m the eldest son and I feel very responsible both for the business and for the family and to my father for having achieved so much.’ However, the idea of hardship is one means of linking two generations of family entrepreneurs. As Chapters 6 and 7 illustrate, successful businesses are built through the effort and sacrifice of the founding entrepreneurs. In this context parental sacrifice (which, as Chapter 6 reveals, men claim for themselves) is exchanged for a son’s loyalties to the founder, the family and the business. The financial director of the ‘new’ international export business elaborates: ‘My friends thought I’d go straight into a directorship, you know the silver spoon syndrome. Unfortunately, it didn’t work that way. As soon as I graduated and came up from London I ended up sweeping the floors and driving vans, labouring, and working my way up. My father didn’t just hand me this.’ Similarly, the heir to the civil engineering business pitted the establishment of the business against his father’s efforts, a timely reminder of what is expected from him: ‘We were, very fortunately, born into this family and have got a lot of things that other people haven’t got. But what we were given was an appreciation of how hard my father had to work to get us here. The point to appreciate is that other people are striving to get as far as he has. The reason my father has survived is that he is very professional about the service he provides and the quality of the work he does. And although I have made major changes in steering the business away from the kind of work Dad did, nevertheless I work on the same principle.’ The prevailing theme running through these comments is the dialectic between privilege and hardship, and privilege and responsibility, suggesting the repercussions of profligacy among business successors. This shows another aspect of the logic of substantive rationality (Roberts and Holyroyd, 1992) when particular values are encouraged in order to preserve the processes of wealth creation. Daughters are excluded from this process and receive a different type of education. Even when they demonstrate an interest and acquire 172 Class, Gender and the Family Business appropriate skills, the assumption is that they lack that mysterious but most definitely male quality called leadership, something which wives also apparently lack. This gendered and exclusionary practice constitutes part of the shared business culture, which can be made sense of when again drawing on Robert’s and Holyroyd’s (1992: 159) notion of substantive rationality. What is seemingly a particularistic practice is underlined by a version of modern rationality, when senior male kin calculate the potential in what is also a familial relationship to develop the growing empire, by choosing a son imbued with the appropriate qualities who will succeed as future leader. Whilst the purpose of this virtual apprenticeship is to identify and train suitable managerial leaders and heirs for the family business, it is strongly tied in with primogeniture, a practice long associated with the propertied classes, when the core property is passed along the male line, and where the eldest son is given first choice (Thompson, 1976). At the appropriate moment the carefully chosen and trained heir assumes his rightful inheritance, repeating the long-established practice of primogeniture. The belief is that the heir should also be the sole owner, or is the majority shareholder giving him the power to control the business. However, in vertically integrated businesses, male siblings who demonstrate worth and appropriate skill may be appointed to senior positions within the business. The negative side of such management practices is that they bar female siblings from effective participation within the family business. The dyeing and textile manufacturing and export business highlights the ways in which girls are discriminated against within the family firm. The son had inherited the dyeing business, whilst the daughter had a temporary post in his business. Although they are equally qualified, their positions, status, authority and sense of involvement are very unequal. The son, aged 28, is director and heir, and has responsibility for one of the plants. After university, he spent a year with another company in sales insurance prior to joining the business, and claims to have ‘worked his way up from the shop floor’ where he learned the practical side of the business. Typically, such a meteoric rise within the family business is not an experience that is shared by daughters unless they are the chosen heirs. His sister is two years younger. She has a degree in fashion design. She is also interested in dyeing and wants to work in the business. However, she described herself as a freelance fashion designer whilst ‘helping out’ on a temporary basis. Her career ambitions are, nevertheless, firmly located within the business, and she intends to do further The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 173 training in dyeing with a view to greater involvement. The next comment illustrates the rivalry between the siblings and the manner in which the principal heir in this case thwarts his sister’s ambitions. During the interview and unprompted, he interrupts to illuminate his plans for his sister: ‘Well, you see, we don’t expect too much from A. It’s nice to have her around while we can. And although we would like her to be involved, we know there will be a stage when she won’t be with us. She’ll get married one day.’ (Heir to Table 3.1, N11) To which she ruefully replied: ‘Yes, you will be influential. I’ll be married off .’ (Daughter of couple N11, Table 3.1) This comment is illustrative of the manner in which beneficiaries draw on domestic ideologies to undermine the organisational effectiveness of female kin. Rivalry between brothers and sisters of this sort is not uncommon, and like the wives, female siblings do not always acquiesce to male domination. Despite the brother’s disclaimer, this woman has very clear ambitions within the business, but her job gives her very little authority. The brother’s position, by contrast, gives him much more authority. In such situations, female kin are often constrained not only by their lack of power, but also in ideas of family loyalty (Cohen, 1974). To protest would be to break rank. It is not the lack of appropriate skills amongst women as the male partners argued in the earlier chapters, but rather male dominance which accounts for female ambivalence. As these examples of ‘new’ business families demonstrate, the senior positions men hold are due to the differential treatment of sons and daughters. As such, this activity represents yet another strand in an overall strategy of female exclusion. There are two levels in which Bourdieu’s (1976) notion of habitus explains this. First, decisions are made according to tradition, where customs define the relationship between the business and the family in the expectation that the particular managerial approach will safeguard the business and the social status of the family. At a second level, it reveals the manner in which the actions of middle-class business families are socially and economically embedded class practices, because, by 174 Class, Gender and the Family Business developing and protecting the business, they also maintain their social class status. Business opportunism, social capital and ethnicity The third dimension of the notion of a shared business culture refers to the idea of business opportunism. Business opportunism is best described as a business practice which extends beyond the formal boundaries of business activity and engages forms of social relationships which are instrumental in intent. The value of social relationships is that they either create or access business opportunities, a feature of majority and ethnic minority business. In this sense, exchange and value underlie different permutations of social relations. Exchange underpins Burt’s (1992) notion of social networks, Boissevain’s (1974) social entrepreneurs, Yancey et al.’s (1976) notion of manufactured ethnicity and Werbner’s (1990) discussion of the cultural meaning attributed to gift-giving and wedding attendance among Pakistani Muslims. Although they are rooted in different cultural settings and their outward expression is social in form, they are in essence instrumental and opportunistic, and create what Burt (1992) calls social capital. The value in these relationships is that they are an information resource to the business. There are different expressions of how social capital operates. For instance, Boissevain’s (1974) notion of the social entrepreneur in which the individual through family and friends builds up a system of credits in which s/he is owed favours best describes the manner in which a migrant entrepreneur from India first entered the property market and built up a markedly successful business in estate agency and property development. At first the banks refused him a mortgage and he was forced to seek funds amongst friends: ‘I saw this house, it was £1,200; the problem was money. I borrowed £400 from each of three friends and told them I’d pay them back within the year. I then rented that house as well as doing all the overtime I could. I paid back the first £50 to each of them within three months, and I kept my word. Then some were bringing their families from India and I helped with that and getting them a house.’ He bought a cheap house, and became a landlord to his co-ethnic friends and other incomers. They pooled their earnings and savings in order to finance individual family commitments providing housing and The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 175 family support, but the quid pro quo was that this arrangement also facilitated his ambitions as a landlord for he bought additional property, which he then financed and managed on the basis of rental purchase (Dahya, 1974). This was a temporary measure for he secured co-operation from the banking institutions by being able to demonstrate the viability of his business plans. On the other hand, being a member of a particular group, or social network, can be used to create what Burt (1992) defines as structural holes. For instance, an Asian business head wanted a business partner he could trust in order to implement his plan, which was to purchase and operate a knitwear and a dyeing plant, both of which were expected to go into receivership: ‘I came from Uganda in 1972 and I opened some retail shops, then in 1974 I started another business buying and selling second-hand cars. I wanted to go into something bigger and was interested in a knitting factory. It was very difficult to raise money from the banks, but in my case it was OK. I only wanted to borrow a small amount which I did successfully because I knew this particular bank beforehand. I mean in Uganda I was the distributor for Citroën cars, so I had a big account and international connections. At this point I really wanted a business partner to come in with me. I put my proposal to a business colleague and with his help I got the factory. Since then I have bought him out.’ First, through his circle of friends he was able to find a business partner, while this group also acted as a source of essential information which enabled him to act at key moments, thus ensuring he secured the businesses at the best possible price. Social class identity through an informal social network of friends was a very important factor in the creation of a business opportunity when an Anglo-Jewish merchant banker secured a much desired house, which he subsequently developed into a hotel: ‘I had a job in the City in merchant banking and while it was interesting and rewarding, it wasn’t everything. I wanted to run my own business and didn’t really want to work for someone else. I wanted to combine this with living in the country, and I was interested in fine food and wines. I used to come down to the country at weekends. I rented a cottage on E. estate and used to do a bit of riding and golf, got to know a few locals [rural gentry]. One of the families had this rather nice house to sell, and heard that I was interested in a business. It all gelled, it was the beginning of 176 Class, Gender and the Family Business the 1980s, there was a lot of new money around, and a new interest in haute cuisine, and this local family had this wonderful house, which would be ideal for a top class country hotel. Lady L. didn’t want to just sell the house and through some other friends she contacted me, we made a deal, well she knew that I’d restore it. I bought it, and it is the hotel at O. We opened it in 1980. It was just perfect.’ In this case it was the respondent’s shared social class identity that led to his notion of the ideal business opportunity which would combine earning a living with a particular lifestyle. It was this loose network of social connections, weekend visiting, membership of the hunt, playing golf and through visiting the local pub that fostered a communication network which led to the creation of a business opportunity. Equally, it was by being privy to crucial information though social connections that another majority entrepreneur was able to buy back very valuable property at a vastly reduced price, from a 1980s highflying entrepreneur, just prior to the latter’s fall from grace at the beginning of the 1990s: ‘I had this huge house and really it wasn’t feasible to open it up to the public, it hadn’t enough of nice things in it . . . It was very difficult to maintain, needed a new roof, was cold and draughty. A business friend said, “MM is looking for a property”. The idea was a country hotel. In a throwaway line, I said, “He can have my house – A. Hall”. This was how it started. Anyway they saw the house and finally decided the’d buy it, but only if I also sold them the 400 acres of woodland. I had their heads over a barrel and asked for more money. I was happy with what they offered, but they wanted me to accept payment in equity in their electronics and fruit business. I was well advised by another friend who knew my buyer not to. I took the cash. Then, very early on, before the whole thing erupted and the rising debt and so on, I decided to buy my land back and made an offer but was obliged to take the house as well, but I bought them cheaply. By this time I knew L. was interested in buying and restoring the house.’ Another respondent explained that it was information from another friend that led this particular respondent to put in an early bid to repurchase the property. The advantage of social connections to these individuals was that they were the first to access important items of business information which were tactically crucial. The importance of these The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 177 networks is that they are not explicitly exclusive, but they are implicitly inclusive. Essentially, they provide informal settings in which business opportunities can be explored while participants engage in activities which are ostensibly social in character and reputation-enhancing, but are instrumental in essence. Aside from the loose networks described above, some members of all categories of business heads belong to exclusive social organisations. Some of the business heads, regardless of ethnicity, are members of the same clubs, particularly Masonic Lodges and The Lions Club. On the other hand, each category belongs to exclusive clubs. For instance, many of the ethnic minority heads belong to a Business Dinner Club. A few of the white majority entrepreneurs are members of gentlemen’s clubs. Many of the ethnic minority as well as white majority entrepreneurs give generously to sports and charitable societies, and this has the effect of enhancing their social status and reputation among the wider community. The fact that the most affluent ethnic minority business heads are increasingly members of white majority clubs may signal a tentative departure from social inclusion based on ethnicity to one embedded in a social class identity. However, what is also clear is that such heads draw a distinction between public and private activity, and are keen to maintain the regulation of domestic activity within very narrow ethnic boundaries. Conclusions This chapter has attempted to transcend conventional accounts of business behaviour among different ethnic groups, in which ethnic identity appears to heighten assumed differences. It has been argued that similarity also describes ethnic minority and white majority business behaviour within family firms, and that it has kinship and class roots. A number of key shared business strategies and beliefs were identified which are bounded by a fusion of particularistic and universal rationality that is embedded in the material reality of the family and the business. The businesses are generated and perpetuated by the family, primarily to ensure the survival and well-being of the family, and also for the good of the community. The family business as an institution provides the conditions for self-realisation for a few privileged male kin, but it is perceived to be a mechanism of protection for wider kin members in a hostile and predatory economic environment. On the other hand, ownership and the rights and responsibilities traditionally associated with it can be preserved and incorporate a 178 Class, Gender and the Family Business commitment to local employment, and in some instances to the preservation of a specifically British industry. For instance, in one case a very successful speculative builder and estate farmer argued that British manufacturing could be restored only through indigenous ownership recapture. At the time of the interview he had bought the last remnant of the British motor cycle business and had returned it to profitability. It has been argued that while ethnic minority capital may appear more fluid, this is a way of shifting out of peripheral sectors and embodies an accumulating strategy, which leads to more stable and prosperous economic environments. This search for stability and continuity is also linked to the desire to retain personal ownership, control and contingent advantages. Private owners appreciate the value of trust and commitment, and they fear that it will be lost if their companies are floated. There is a strong commitment to private ownership and there is disinclination to float their businesses based on the belief that it would be unlikely to lead to greater growth. The discerning external shareholder and city institution were viewed as poor business partners and were perceived to be more interested in fast returns than in company development. The focus of the chapter was on a number of successful businesses which included ethnic minority businesses who compare favourably with their white majority counterparts. Although they can be described in Jones’s (1976) terms as an exceptional minority, most of them began from the vantage point of being largely middle-class with its attendant advantages, which released opportunities. Although these entrepreneurs appear to represent a growing group, they are not representative of their communities. While the call to enterprise may well have been heard, when as Werbner (1990) notes that redundant ethnic minority workers took on the entrepreneurial challenge, the absence of redundant workers-turned-successful entrepreneurs in this regional study seems to confirm the view that enterprise within the white majority (Rainbird, 1991) and ethnic minority communities is little more than an alternative to unemployment for most entrants (Aldrich, 1975, 1980; Anwar, 1979; Bonacich and Modell, 1980; Hoel, 1982; Morokvasic, 1987; Bonacich, 1988; Phizacklea, 1990; Scully, 1994). This study acknowledges and provides some examples of exceptional success for a very small number of white and migrant labourers, who have built large and successful businesses, yet it does not support the rags to riches message, the essence of neoliberal entrepreneurial theories and cultural explanations. Rather, it suggests that, despite racial discrimination, most of the ethnic minority entrepreneurs, and in particular those from East Africa The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies 179 and Anglo-Jewry, built on their strengths and started or re-established their businesses from a material, or social class vantage point which is strategically significant. These particular heads have been able draw on good educational credentials, business skills and social and financial capital, credentials which are easily comparable with those of their ethnic majority counterparts, who were also significantly advantaged. 10 Conclusions In exploring the interplay between the configuration of class and gender relations that characterises the family enterprise this book has challenged popular stereotypes of family women as marginal helpers in the family enterprise. Alternatively, it has demonstrated the centrality of female kin in the family enterprise and in this sense the contribution this book makes is that it establishes that they are critical to the formation of wealth within the boundaries of the family enterprise. In arguing this point, masculine ownership has been questioned to reveal a complex and close but changing relationship based on a constellation of vested and shifting interests between men and capital suggestive of Hartmann (1979) and Walby’s (1986) dual theory approach. Illustrative of Pateman’s (1988) argument, correspondingly it has been argued that the relationship between family women and capital is mediated by the dynamics of the power relationship between men as husbands and women as wives and leads to women’s systematic exclusion. In this sense masculine ownership symbolises two sides of the same coin, with men on the one side and capital on the other, whereby the unity of married partners represented in male ownership conceals the embodiment of women’s efforts. It has been argued that this is a problem for the entrepreneurial wives in business partnerships with their husbands for it is difficult for them to gain recognition as entrepreneurs, and this perpetuates gendered stereotypes. In this sense, then, it is suggested that family men define women’s relationship to the particular capital formation in respect of their actual contribution to capital accumulation, terms of reward and the appearance of this relationship. By exploring the different ways in which such wives have contributed to the business it is argued that family women’s labour and capital forms a key strand in a business strategy that maintains and sustains the family 180 Conclusins 181 enterprise. However, the women partners are not appropriately rewarded and are not recognised for their contributions, while at another level the manipulation of domestic ideologies rather emphasise their domestic role and overshadows their role in the business. In Chapters 6 and 7 it was shown that the perpetuation of such enterprise rests on women’s domestic role and on the rearing of the next generation of entrepreneurs and the maintenance of the emotional and physical well-being of husband partners, the current entrepreneurs. The issue of women’s recognition lies with entrepreneurial men’s view of the wifely role and is influenced by what are deemed to be the priorities of the time. Whilst not intending to suggest economic determinism it is clear that the male owners of considerable capital attempt to regulate women’s points of entry and exit according to the exigencies of the accumulation process, which for the women is mediated by cycles of productive labour and reproductive work. In this instance, men’s interest is to retain their dominance over the regulation of the female kin so that the needs of the business are taken account of from an immediate and strategic perspective. Such entrepreneurial men also rely on a network of relationships closely aligned with capital to achieve this. This involves a process, which culminates in the exclusion of female kin from the family firm and is explained by the specific nature of the research sample that includes newly created and inherited businesses. This particular research approach facilitated the emergence of data that have suggested that the family enterprise can be conceptualised as a process that involves three distinct phases, the phases of wealth creation, accumulation and preservation, and can be imagined from a lineal and a cyclical perspective. This conceptualisation has provided the framework in which it has been possible to trace the business partners’ careers through the organisational structure and the evolution of the enterprise. This question has been examined in Chapters 3–5 and aligns each of the phases with the evolution of the wives’ careers within the family enterprise. First, it is argued that, in times of necessity, such as the phase of business start-up and the operational management of established enterprise, men enthusiastically draw their wives into the enterprise where they perform a variety of functions. During the second phase, when the business is organised hierarchically exhibiting divisional functions that require professional and executive personnel, professional staff are substituted for the wife/partners, who often at this point are placed under increasing pressure to return to domesticity. It is at this point, when such wife/partners have made significant contributions to the enterprise, have gained considerable 182 Class, Gender and the Family Business experience and not unreasonably expect to continue to play a significance role within the enterprise, that their husband/partners are concerned with the question of reproducing the future heirs and managers for their businesses. Despite these expectations and the knowledge and experience they bring to the enterprise, they are not perceived to be contenders for such posts. In fact, the very existence of such formal structures, processes and procedures parallel the expendability of such wife partners. This makes some important points about the question of gender equality. The organisation characterising the family firm fails to treat husbands and wives in business partnerships as like with like in respect of the value of credentials and experience. In very many cases both male and female entrepreneurs have broader skills and specific credentials that almost perfectly match or can be transferred to useful and applicable knowledge in the management of the family business. However, mirroring Savage (1992), it is clear that for these women credentials are not effective in helping them progress into senior managerial roles. Even where such women succeed to the role of director they seem to lack sufficient discretion and authority, and are excluded or leave the business. Arguably, the boundaries in which the question of choice operates and the opportunities for family women to enter senior managerial distinguish the family enterprise from corporate business. Family women find it very difficult to develop a career within the family enterprise and arguably have fewer opportunities and face additional constraints than their counterparts in the corporate sector. Notwithstanding the problems such professional women encounter, exemplified in Davidson (1992) ‘glass ceiling’ syndrome, the entry of family women into directorships does not necessarily enhance their organisational power. Paradoxically, the segregation of women managers into specific sectors, reported by Coyle (1989) and Grant and Porter (1994), has resonance for family women managers. For instance, their work as operational managers both protects and limits their career opportunities. Comparing the family women managers with Wajcman’s (1998) corporate women managers suggests that family women in private enterprise are constrained in a particular way through the conflation of their professional and private roles. In this instance, husbands acting as principal decision-makers draw the boundaries around family women’s and particularly wives’ career options. This limits family women’s power to control their careers and career progression within the family firm. By contrast, Wajcman’s (1998) study suggests that corporate women are better able to utilise a strategy. The women who Conclusins 183 succeeded to senior posts adopted a male approach to work, which suggests some idea of choice between possible options. In order to succeed, corporate women may have acted strategically and have chosen options that were more likely to accommodate career progression. Grant and Porter’s (1994) work implies the importance of a career strategy when they argue that the women managers they studied adopted a management style that was different from the characteristic organisational style. These studies indicate that, despite the difficulties, there are possibilities for women’s careers in the corporate sector, whereas the research on which this book is based suggests that the idea of wife/partner pursuing a career comparable with her partner within the family business for the immediate future is limited. Undoubtedly, this will depend on a reorganisation of the relationship between domesticity and capital, because presently the onus is on the women to negotiate around the twin powers that arise from the dual power of men and capital. Of course, this does not rule out that there may be some change in the longer term, but this would also involve critical changes to an overall, highly coherent and established strategy that appears to have offered a sustaining formula for the male management of private enterprise. Echoing Witz (1992), this book suggests that credentials and professionalism have little influence for the wife/partners, while for the entrepreneurial men they have proved to be a sustaining resource guiding the male partners through the phases of business development. The question of the relationship between experience and practical knowledge and business management makes clear the importance that gender difference has for career progression in the family enterprise. Chapter 6 shows that entrepreneurial men rely on their experience of establishing an enterprise as knowledge for the further development of that enterprise and simultaneously establish their reputation and image. In the case of the entrepreneurial working-class model, and suggestive of Sennett and Cobb’s (1977) study, this book demonstrates that such men are also able to compensate for the lack of formal education by building identities around notions of thrift, effort and sacrifice in ways that tie into, and are compatible with, human capital theories, entrepreneurial ideologies and popular stereotypes. By contrast, women entrepreneurs have no such anchor. Rather, this book emphasises that resources such as education, skill, labour and capital in co-ordination with the institution of the family enable some men to transcend structural constraints. By contrast, and while acknowledging that there are exceptions, wife/partners find it almost impossible to establish themselves as credible professionals within the family enterprise. Unlike their 184 Class, Gender and the Family Business male partners, family women are unlikely in the longer term to remain within the enterprise or develop very successful careers, although they have by this time gained considerable expertise. Indeed, as the discussion about emotion work in Chapter 7 reveals, it is women’s exclusion from a professional role and their return to domesticity that allows such men to carry out their economic role and sustain the image of the ‘family man’ on which such enterprise is based. This chapter also shows that the form and content of the women’s role is contested between husbands and wives. The book has also shown that the phase of wealth preservation culminates with the exclusion of women from ownership. As the discussion in Chapter 5 reveals, primogeniture is the key mechanism that sustains the dominance of men’s relationship with capital thus endorsing Engels’ (1972) argument, which shows the link between the logic of father right and ownership and the maintenance of the male line. Chapters 3–5 show that husbands enjoy the power endowed with ownership, such as combined senior managerial roles and decision-making which equate with a career, power, affluence, independence and fulfilment, while their wives formally fail to move beyond their stereotypes. Resonant of the Pateman’s (1988) analysis of the marriage contract, this book has argued that explanations for this lay with the power that husbands have over their wives and their ability to bring pressure on them in terms of balancing career choices with domestic responsibilities. In turning to men’s relationship with enterprise in Chapter 9 it is argued that business families pursue a set of practices that, over time, can be understood as a strategy. As Chapters 3–5 illustrate, the first strand of this strategy involves the utilisation of women’s labour in the creation and management of enterprise and their eventual exclusion from ownership. Second, Chapter 6 argues that the second feature of such business strategy is the tendency for male emotion to be reserved for business activity. Ochberg’s (1987) analysis of the manner in which men seek to control and regulate their own emotions has been drawn on to illustrate how this occurs. In this context, it has been argued that contemporary capitalism has witnessed the concealment of male emotion in the public sphere and the elevation of ‘hard’ masculinity (Brod, 1987; Hearn, 1987; 1994; Seidler, 1989; Brod and Kaufman, 1994), and that both are critical attributes of a family business strategy. In examining popular discourses that portray business leaders as ‘selfmade’ men, and based on the differential availability of resources such as capital, labour and education, this book has revealed two entrepre- Conclusins 185 neurial models, a migrant labouring/working-class model and a middleclass model, and different kinds of entrepreneurial men. Whilst it is acknowledged that there are some important differences between the men that represent the different models, it is argued without reservation that all entrepreneurial types privilege their economic role and conserve their creativity by withdrawing from emotion work within the household. Equally, they all have normative expectations that female kin will fulfil their emotional work. Also notions such as ‘self-made’ and sacrifice are intimately connected and bridge the gap between the men’s corresponding roles as capitalists and family men. A good example of this, illustrated in Chapter 6, shows that, while men devote their lives and their energies to enterprise, they almost all see their leadership training and privilege as a ‘sacrifice’ of the self in the interests of the family and the survival of the business. Whilst accepting that these stereotypes have some reality, especially for the migrant labouring/working-class men, the research found with some ambivalence that all entrepreneurial claim they have been sacrificed. The other point to note is that, similar to their middle-class counterparts, working-class entrepreneurs make huge demands on their wives. In some instances the organisation of the household accommodates the arduous physical work and working patterns that become one of the hallmarks of the way in which such men compete in the market. On the other hand, the women ultimately resent and challenge their husbands’ dedication to the business and absence from home. It should also be noted that this book does not concur or support the neoliberal idea that poverty and disadvantage can be overcome by the adoption of the prescriptive human capital approach. The small number of migrant labouring/working-class entrepreneurs who established ‘new’ businesses were well served, not least by the financial management of the enterprise, a skill they often had already acquired, and by the economic exigencies of the particular period that afforded them not only business opportunities, but also access to niche labour markets and configurations of class relations upon which their fortunes were built. Perhaps in the context of white majority entrepreneurs, Jones’s (1976) notion of ‘exceptional minority’ aptly describes them. In Chapter 9 it is argued that family capitalism is characterised by a shared business culture rooted in the experience (Bourdieu, 1976) of the cyclical process of re-creating, managing and preserving business. Culture in this context refers to the manner in which leadership and questions of succession are approached and the financial management of such enterprise. Of special significance to this overall strategy is the 186 Class, Gender and the Family Business question of primogeniture or the tendency for established business families to favour male children as the future owners and managers of the enterprise. Tied into these features, it has also been shown that other major aspects of this strategy are a particular approach for the production of specific kinds of human capital and entrepreneurial expertise. Part of this strategy also encompasses a preference for the internal sourcing of investment capital, risk avoidance in respect of business growth and a reliance on family labour and the nurturing and utilisation of social capital (Boissevain, 1974) or structural holes (Burt, 1992). The rigidity and continuity in patterns of economic behaviour, and especially the repetitive character of the creation, management and preservation of the family enterprise, put into context the notion of habitus (Bourdieu, 1976). This raises the thorny question of how change and the scope for agency are accommodated within such a seemingly rigid framework. For instance, patterns of ownership underpinned by a particular configuration of gender relationships and gender power also reveal remarkable continuity. Roberts and Holyroyd’s (1992) notion of substantive rationality explains this and another important manifestation of continuity. These refer to the primacy given to primogeniture and a patriarchal family culture that presides over the organised privileging of male children over their female siblings in education, training and career expectation, resulting in substantive gendered differences between male and female kin. The ideal is that family men and women follow tradition and the rigidities of the sexual division of labour, which means that female kin will find difficulties when trying to carve out a professional role. Second, such discriminatory practices serve the interests of the male line and, rooted in earlier class gender systems, they insist that women’s first duty is to provide the generations of entrepreneurs and managers. This is a critical part of the family business strategy for it aims to produce business heirs and managers from within the family. However, this kin-based strategy does not contradict modern rationality, but is rather compatible with and borrows from contemporary capitalist configurations. The book has shown that such instances of collaboration hinge on an education and a socialisation that endows boys with the kind of financial knowledge and leadership qualities (real and perceived) that equip them with sufficient skill appropriate for business management. As the examples of the women owners in Chapter 8 show, unless they are critical to enterprising activity, women are not considered as future heirs and are largely excluded from training. The experiences of the working wives show that these practices generate a Conclusins 187 system of values and beliefs that, when combined with gendered kinship power, are very difficult to challenge in bids for the financial management of such enterprise. Moreover, as the earlier chapters show, the husband/partners refused to see their wives as business leaders, but drew on rigid gendered stereotypes to suggest women’s incompetence with regard to financial management. This does not suggest that the men did not view their wives as business partners; however, continually suggesting that such women’s competence lay in creativity (fashion design) or nurture (various personnel posts) indicates that they saw this work as complementing the key role of financial management. What the evidence suggests is that such entrepreneurial men drew in this case on patriarchal power to differentiate between themselves and their wife partners. However, Brod’s (1994) illuminating arguments surrounding masculinities would suggest that this is simply another manifestation of how competitiveness is used in the quest for capitalist power. In this instance, men and capital are two sides of the same coin, when individuals are driven by compatible interests, the logic of capitalist competitiveness and male supremacy. Although the research has reported some resistance from female kin, it did not necessarily endanger business survival. This limited resistance must be understood in terms of interests, for the ‘successful’ family enterprise enhances and safeguards the class location of family members, and female kin and children born into such families are relatively advantaged and benefit materially. This discussion portrays a pattern of consistency manifested in the manner in which heirs and managers are selected and subsequently compete for power within the family enterprise. However, the scope for autonomy and agency within the family business lies with financial strategy and is particularly evident in the diversification of such enterprise and the peculiarity of capital investment. Characteristically risk-averse, it is argued that such enterprise shifted investment to safe sectors of the economy such as property and land, which, according to Wedgewood (1929), is a long-established way of safeguarding private wealth. Reflecting particularistic values and in relatively safe economic environments these businesses studied survived by selectively borrowing from market capitalism to safeguard and expand their business assets on behalf of the wider family interests, thus securing their class location, status and lineage. In arguing that family business strategy is located in class identity, this book has challenged cultural explanations that reflect supply-side 188 Class, Gender and the Family Business economics and align business activity with the assumed supremacy of specific ethnic identities in the field of entrepreneurship and their sectoral segregation on the basis of ethnicity (Werbner, 1990). Starting from the premise of capital assets and taking account of the ethnic identities of the entrepreneurs involved, this study found that all the entrepreneurs pursued a similar business strategy, including Asian, Anglo-Jewish, Irish and white majority entrepreneurs, who share a common business culture. It is also argued that an important dimension of this culture is the manner in which social relationships create or access business opportunities, and this is a feature of business strategy for white majority and ethnic minority business and for men and women business heads. In this sense, it has been shown that exchange and value underlie the different permutations of social relations, characteristic of Burt’s (1992) social networks, Boissevain’s (1974) social entrepreneurs, Yancey’s manufactured ethnicity and Werbner’s (1990) gift-giving and wedding attendance. This does not dispute that these groups are culturally different, yet the logic, meaning and intention of their business cultures are similar, for they are rooted in the cultural settings of their class location, and although their outward expression is social in form, they are in essence instrumental and opportunistic, and create what Burt (1992) calls social capital. As shown in Chapter 9, social capital serves the interests of the enterprise through family friendships and connections, while it introduces a legitimacy to the instrumentality and competitiveness associated with business friendships. Reminiscent of the argument concerned with the contradictions of male friendships, all groups engage in business opportunism when they extend the boundaries of business beyond the formal settings, and participate in networks of friendships that are, or subsequently have, an instrumental dimension. At the same time, social networking masks the divisiveness of male competitiveness (Brod, 1994) characteristic of business opportunism, which is a major feature of business strategy. It is suggested that ethnic minority capital is more fluid and there is greater diversification amongst ethnic minority entrepreneurs. However, this is a way of shifting out of vulnerable and peripheral sectors, and replicates a broader accumulation strategy that leads to more stable and prosperous sectors of the economy, such as property and land. In finding that ethnic minority business compares favourably with that of their majority counterparts, the research has drawn on Jones’s (1976) notion of exceptional minority to describe this group. It has been argued that, with two exceptions, the ethnic minority entrepreneurs like their white majority counterparts started business from a Conclusins 189 considerable vantage point of being middle-class with its attendant advantages, which released opportunities. It is their very real resources that include capital, appropriate skills, knowledge of the business world and their networks that explain their success as business leaders as opposed to reference to culture or rags-to-riches stereotyping. There are two models of entrepreneurial behaviour – the migrant labour/working-class model and the middle-class model – a typology that is intended to show how the differential availability of resources affect working-class and middle-class business leaders at the phase of wealth creation. The difference is that without resources, working-class entrepreneurs work for long periods and save investment capital prior to business entry, although Chapter 6 shows that there are differences in their approach to wealth accumulation, a difference exemplified in the two entrepreneurial types, the company man and the takeover man. Arguably, these differences to some degree are products of the economic exigencies of the time, and having reached the accumulation phase, the second phase in business development, regardless of initial market approach in the phase of creation, both typologies of business leader adopt similar conservation strategies. They also engage in ostentatious intra-generational class mobility and emulate middle-class social norms exemplified in the provision of private education for children and the acquisition of palatial private dwellings. The evidence discussed in this book might suggest that there is a particular approach to business that is likely to result in business survival and renewal. However, this is not the intention, for the results reported merely reflect the outcomes from the combination of the particular research approach, findings, interpretation and analysis. However, the findings strongly suggest that frugality, prudence, caution and a commitment to long-term investment characterise the management of such family enterprise. In examining the management of the family business, this book has argued that such enterprise is organised around a family strategy that, taking into account the interests and the survival of the businesses into consideration, also succeeds in safeguarding the social and class status of the family concerned. At the same time, this book has shown that the firm provides a very solid foundation for the reproduction of social class relations. In exploring the relationship between enterprise, gender power and class relations, this book has revealed a network of power relations that sustains the rigidity of patterns of inequality within capitalist families. In drawing attention to the relationship between women, men and capital and private enterprise, this book has 190 Class, Gender and the Family Business contributed to the debate on gender inequality by highlighting the ambiguous class position of female kin, particularly the wives of wealth owners, a position that both ensures their subordination and their relative advantages. Notes Chapter 1 1 Primogeniture is the practice of giving the eldest son the core unit of wealth – the ‘business’, the ‘family estate’ – and constitutes the single most important strategy in the transference of wealth and property across generations, for it safeguards against the disintegration of core unit of wealth (Clemenson, 1982), whilst also serving ruling-class interests. It is only in cases where there is no suitable male heir that women are considered. 2 Under coverture a wife had no independent legal existence, and therefore could not own immovable property such as land, could not make a will, nor present herself in court, while she herself was under the ‘protection’ of her husband. This combination has two effects for the preservation of wealth. By denying wives ownership rights, it safeguards the fragmentation of wealth, and by entrusting guardianship of the wife to the husband, it ensures the control of her sexuality and labour, protecting paternity and the male line. To become a wife was to become disinherited, for the property women brought to the marriage became the property of the husband under coverture. This monstrous institution systematised wives’ subordination, and survived from the 1250s until 1925, having undergone a series of reforms in the passing of the Married Woman’s Property Act of 1882 extending women’s right to property. 3 ‘In reality the generating and unifying principle of practices is constituted by a whole system of predisposition’s inculcated by the material circumstances of life and by family upbringing, i.e. by habitus. This system is the end product of structures in which practices tend to reproduce in such a way consciously by re-inventing or by subconsciously imitating a ready proven strategy as the accepted, most respectable, or even simplest course to follow’ Bourdieu (1976: 118). Chapter 2 1 The nineteenth-century perception of landowners living off rents and unearned income has little validity today. Only one landholding with an extremely large acreage of 20,000 acres and a vast commercial property portfolio, bore much resemblance to the activities of the nineteenth-century rentier class. 2 This means that those who inherit a business as well as those who create a business adopt similar business strategies. For instance, those who create a new business will want to expand it and make it secure. On the other hand, those who inherit a business may need to seek out new ways of surviving in a changing economic environment and may diversify. 191 192 Class, Gender and the Family Business 3 This refers to the nineteenth-century idea of the wife of the aspiring enterprising man. The role of the wife was to offer unquestioning support to her husband, whilst carrying out her domestic role with both emotional and financial efficiency invisibly in the shadows of her spouse (See Davidoff and Hall, 1987.) Chapter 3 1 The research in a limited way found that the dowry system was also important. In one of the ‘old’ families studied, family wealth was established, followed by their ascendancy to political power through the marriage of an ancestor to a European heiress with a large dowry. In another case (descendant not interviewed) the ancestors of an extremely rich aristocrat had acquired their wealth in a similar way. Sometimes women were valued for their breeding and status attracting money and in such cases men married upwards. For example, in another of the ‘old’ families the respondent’s ancestor had made a lot of (industrial) money in brewing and was able to marry into the landed aristocracy. 2 Turning to the issue of women’s labour prior to the capitalist era when the line between use-values and exchange-values remained blurred within the mode of production, it can be assumed that women from all classes were engaged in some way in economic activity. In discussing the feudal era, Middleton argues that women amongst the peasant classes played a direct economic role in the production of exchange-values, whilst wisely acknowledging the sexual division of labour, the dominance of housework and servicing of men as women’s key role. However, what is much more in doubt is the extent that they managed their income (Erickson, 1993). But as I later argue, the law of coverture very much favoured male control over women and their products, thus severely compromising female autonomy in such matters, as the management and ownership of income and wealth. Chapter 5 1 This a legal term stating that an estate or property cannot be divided. Partition of the property must not take place. See Collins English Dictionary, second edition. 2 ‘Widow’s right by custom of the manor, to continue in possession of the whole or portion of husband’s lands during her life’ (Thompson, 1976). See also Erickson (1993: 24). Chapter 6 1 A system of casualised employment conditions that has a very poor health and safety record, long associated with the construction industry. (See Austrin in Nichols, 1980.) Notes 193 Chapter 7 1 A ‘good wife’ in the mould of Sennett and Cobb’s (1977) Mrs O’Malley uncomplainingly takes on the burden of family stresses and strains. Chapter 9 1 A structural explanation of the development and growth of ethnic business that considers the constraints and the opportunities. An example of middleman minority (Bonacich and Modell, 1980) is the Indian immigrant business sector in East Africa, which consisted of traders and merchants. From a social class perspective they were located between the Europeans and the indigenous Africans. According to Bonacich they filled in a status gap that was created by the dominant and subordinate classes who did not wish to interact, but who relied on each other. 2 Refers to a structurally peripheral economic sector, where businesses are characteristically small-scale. An example is the small retail business that is largely owned by ethnic minority owners. A second feature of enclave theory is that such businesses are restricted to enterprise in their localities serving ethnic minority and working class customers. References Alderman, G. (1983) The Jewish Community in British Politics, Oxford and New York: Clarendon Aldrich, H. (1975) ‘Ecological Succession in Racially Changing Neighbourhoods: A Review of the Literature’, Urban Affairs Quarterly, 10, 3 Aldrich, H. (1980) ‘Asian Shopkeepers as a Middleman Minority: A Study of Small Asian Business in Wandsworth’, in Evans, A. and Eversley, D. (eds) The Inner City: Employment & Industry, Heinemann: London, pp. 398–408 Aldrich, H., Cater, J.C., Jones, T.P. and McEvoy, D. (1981) ‘Business Development and Self-segregation: Asian Enterprise in Three British Cities’, in Peach, C., Robinson, V. and Smith, S. (eds) Ethnic Segregation in Cities, London: Croom Helm, pp. 70–2 Aldrich, H., Jones, T. and McEvoy, D. (1984) ‘Ethnic Advantage and Ethnic Business Development’, in Ward, T. and Jenkins, R. (eds) Ethnic Communities in Business, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 189–211 Allan, G. (1982) ‘Property and Family Solidarity’, in Hollowell, P. (ed.) Property and Social Relations, London: Heinemann Educational Books Allat, P. et al. (eds) (1987) Women and the Life Cycle, Basingstoke: Macmillan Allen, S. (ed.) (1993) Women in Business: Perspectives on Women Entrepreneurs, London: Routledge Allen, S. and Truman, C. (1991) ‘Prospects for Women’s Business and Self Employment in the year 2000’, in Curran, J. and Blackburn, R. (eds) Paths to Enterprise, London: Routledge Anwar, M. (1979) The Myth of Return: Pakistanis in Britain, London: Heinemann Anwar, M. (1986) Race and Politics, London: Tavistock Publications Baines, S. and Wheelock, J. (1998) ‘Reinventing Traditional Solutions: Job Creation, Gender and the Micro-Business Household’, Work, Employment & Society, 12, 4, pp. 597–601 Barrett, M. and McIntosh, M. (1980) ‘The Family Wage’, Capital and Class 11, pp. 51–72 Becker, G. (1985) ‘Human Capital, Effort and the Sexual Division of Labour’, Journal of Labour Economics, 3, 2, pp. 33–58 Beresford, P. (ed.) (1991) The Sunday Times Book of the Rich, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson Bhachu, P. (1985) ‘Women, Dowry and Marriage among East African Sihk Women in United Kingdom’, in Brettell, C.B. and Simon, R.J. (eds) International Migration: The Female Experience, Totowa, N.J., Rowman & Allenheld Blaschke, J. and Boissevain, J. (1990) ‘European Trends in Ethnic Business’, in Waldinger, R. et al. (eds) Ethnic Entrepreneurs, London: Sage Boissevain, J. (1974) Friends of Friends, Oxford: Basil Blackwell Boissevain, J. et al. (1990) ‘Ethnic Entrepreneurs and Ethnic Strategies’, in Waldinger, R. et al. (eds) Ethnic Entrepreneurs, London: Sage Bonacich, E. and Modell, J. (1980) The Economic Basis of Ethnic Solidarity in the Japanese American Community, Berkeley: University of California Press 194 References 195 Bourdieu, P. (1976) ‘Marriage Strategies as Strategies of Social Reproduction’, in Forster, P. and Ramun, P. (eds), Family and Society, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press Branca, P. (1974) ‘Image and Reality: The Myth of the Idle Victorian Woman’, in Hartman, M. and Banner, L. (eds) Clio’s Consciousness Raised, New York: Harper, pp. 179–89 Brettell, C.B. and Simon, R.J. (eds) (1985) International Migration: The Female Experience, Totowa, N.J., Rowman & Allenheld Britton, D.M. and Williams, C.L. (2000) ‘Response to Baxter and Wright’, Gender and Society, 14, 6 Brod, H. (ed.) (1987) The Making of Masculinities, London: Allen & Unwin Brod, H. and Kaufman, M. (eds) (1994) Theorising Masculinities, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Bun, Chan Kwok and Hui, Ong Jin (1995) in Cohen, R. (ed.) ‘The Many Faces of Immigrant Entrepreneurship’, in Cohen, R. (ed.) The Cambridge Survey of World Migration, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Burrows, R. (1991) ‘The Discourse of the Enterprise Culture and the Restructuring of Britain’, in Curran, J. and Blackburn, R. (eds) Paths to Enterprise, London: Routledge Burt, R. (1992) The Social Structure of Competition, Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press Business Week (1992) ‘The Richest 250 Women in Britain’, October, pp. 74– 130 Chell, E., Haworth, J. and Brealey, S. (1991) The Entrepreneurial Personality: Concepts, Cases & Categories, London: Routledge Clark, A. (1982) Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century, London: Routledge Clark, C., Peach, C. and Vertovec, S. (eds) (1990) South Asians Overseas, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Clark, P. and Rughani, M. (1983) ‘Asian Entrepreneurs from Leicester in Wholesaling & Manufacture’, New Community XI, 1/2, pp. 23–33 Chevillard, W. and Leconte, B. (1986) ‘The Dawn of Lineage Societies’, in Coontz, S. and Henderson, P. (eds) Women’s Work: Men’s Property, London: Verso Clemenson, H. (1982) English Country Houses and Landed Estate, London: Croom Helm Cockburn, C. (1983) Brothers, Male Dominance and Technological Change, London: Pluto Press Cohen, A. (1974) Tradition, Change & Conflict in the Indian Family Business, Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts: Moulton Cohen, R. (ed.) (1995) The Cambridge Survey of World Migration, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Collinson, D. (1992) Managing the Shopfloor: Subjectivity, Masculinity and Workplace Culture, Berlin: Walter De Gruyter Collinson, D. and Hearn, J. (1994) ‘Naming Men as Men: Implications for Work, Organisation and Management’, in Gender Work and Organisation. 1, 1, pp. 2–22 Collinson, D. and Hearn, J. (eds) (1996) Men as Managers: Managers as Men, London: Sage Collinson, D., Knights, D. and Collinson, M. (1990) Managing to Discriminate, London: Routledge 196 Class, Gender and the Family Business Connell, R.W. (1995) Masculinities, Oxford: Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Coontz, S. and Henderson, P. (1986) Women’s Work: Men’s Property, London: Verso Cooper, C.L. and Davidson, M. (1982) High Pressure: Working Lives of Women Managers, London: Fontana Cooper, J.P. (1976) ‘Patterns of Inheritance and Settlement by Great Landowners from the Fifteenth to the Eighteenth Centuries’, in Goody, J. Thirsk, J. and Thompson, E.P., Family and Inheritance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Coyle, A. (1989) ‘Women in Management: A Suitable Treatment?’, Feminist Review, 31, 1, pp. 117–25 Creighton, C. (1980) ‘Property and Relations of Production in Western Europe’, Economy and Society, 9, 2, pp. 129–67 Crow, G. (1989) ‘The Use of the Concept of “Strategy” in Recent Sociological Literature’, Sociology, 23, 1 Curran, J. and Blackburn, R. (eds) (1991) Paths to Enterprise, London: Routledge Curran, M. (1988) ‘Gender and Recruitment: People and Places in the Labour Market’, Work, Employment and Society, 2, 3, pp. 335–51 Dahya, B. (1974) ‘The Nature of Pakistani Ethnicity in Industrial Cities’, in Cohen, A. (ed.) Urban Ethnicity, London: Tavistock Publications Davidoff, L. and Hall, C. (1987) Family Fortunes, London: Hutchinson Davidson, M.J. (1992) Shattering the Glass Ceiling: The Woman Manager, London: Paul Chapman Deakins, D. (1996) ‘Asian Firms Break the Mould’, Guardian, 2 April Delphy, C. (1984) Close to Home, London: Hutchinson Delphy, C. and Leonard, D. (1992) Familiar Exploitation, Cambridge: Polity Press Drucker, P. (1985) Innovation and Entrepreneurship, London: Heinemann Eades, J. (1987) ‘Prelude to Exodus: Chain Migration, Trade & The Yoruba in Ghana’, in Eades, J. (ed.) Migrants, Workers & Social Order ASA Monographs 25, London: Tavistock Publications Elson, D. and Pearson, R. (1981) ‘Nimble Fingers Make Cheap Workers’, Feminist Review, pp. 7–9 Engels, F. (1972) The Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State, London: Lawrence & Wishart Erickson, A.L. (1993) Women and Property in Early Modern England, London: Routledge Evans, A. and Eversley, D. (eds) (1980) The Inner City: Employment & Industry, Heinemann: London Felstead, A. (1991) ‘Franchising’, in Pollert, A. (ed.) A Farewell to Flexibility, London: Routledge, pp. 213–32 Finch, J. (1983) Married to the Job, London: Allen Unwin Fineman, S. (ed.) (1993) Emotion in Organisations, London: Sage Finnegan, R., Gallie D. and Roberts, B. (eds) New Approaches To Economic Life, Manchester: Manchester University Press & ESRC Forster, P. and Ramun, P. (eds) (1976) Family and Society, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press Francis, A. (1980) ‘Families Firms & Finance Capital: The Development of UK Industrial Firms with Particular References to Ownership & Control’, Sociology, 14, 1, p. 28 Fromm, E. (1978) To Have or to Be, London: Jonathan Cape References 197 Frost, J.P. et al. (eds) (1985) Organisational Culture, London: Sage Ghillone, B. (1984) ‘Women Power and the Corporation’, Power & Elites 1, 1 Gibb, W. and Dyer, J. (1986) Cultural Change in Family Firms, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Gilbert, N., Burrows, N. and Pollert, A. (eds) (1992) Fordism and Flexibility, London: Macmillan, pp. 154–69 Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory, Strategies for Qualitative Research, Chicago: Aldine Glucksman, M. (1986) ‘In a Class of Their Own: Women Workers in the New Industries in Inter-War Britain’, Feminist Review, 24 Glucksman, M. (1990) Women Assemble, London: Routledge Goffee, R. and Scase, R. (1985) Women in Charge: The Experiences of Female Entrepreneurs, London: Allen Unwin Gooch, I. and Ledwith, S. (1996) ‘Women in Personnel Management – Revisioning of Handmaiden’s Role’, in Ledwick, S. and Colgan, S. (eds) Women in Organisations: Challenging Gender Politics, London: Macmillan Business Goody, J. (1976) ‘Introduction’ in Goody, J., Thirsk, J. and Thompson, E.P. (eds) Family and Inheritance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Goody, J. (1976) ‘Inheritance, Property and Women: Some Comparative Considerations’, in Goody, J., Thirsk, J. and Thompson, E.P. (eds), Family and Inheritance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Goransson, A. (1993) ‘Gender and Property Rights’, Business History, 35, 2 Grant, J. and Porter, P. (1994) ‘Women Managers: The Construction of Gender in the Workplace’, Australia & New Zealand Journal of Sociology, 30, pp. 149–64 Green, R.W. (1959) Protestantism and Capitalism: The Weber Thesis and its Critics, Lexington, Mass: D.C. Heath & Co. Grieco, M. (1987) Keeping it in the Family, London: Tavistock Publications Halford, S., Savage, M. and Witz, A. (1997) Gender, Careers and Organisations, London: Macmillan Hall, C. (1992) White, Male and Middle Class, London: Polity Press Hammond, D. and Jablow, A. (1987) ‘Gilgamesh and the Sundance Kid: The Myth of Male Friendship’, in Brod, H. (ed.) The Making of Masculinities, Boston: Allen Unwin Harding, S. (1987) Feminism & Methodology, Milton Keynes: Open University Press Hartman, M. and Banner, L. (1974) Clio’s Consciousness Raised, New York: Harper Hartmann, H. (1979) ‘The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism’, Capital & Class, 8, pp. 1–33 Harvey-Jones, J. (1992) Getting it Together, London: Mandarcn Heaney, S. (1999) Beowulf, London: Faber and Faber Hearn, J. (1987) The Gender of Oppression: Men, Masculinity and the Critique of Marxism, Brighton, Wheatsheaf: New York: St Martin’s Hearn, J. (1992) Men in the Public Eye: The Construction and Deconstruction of Public Men and Public Patriarchies, London: Routledge Hearn J. (1993) ‘Emotive Subjects: Organisational Men Organisational Masculinities and the Deconstruction of “Emothions” ’, in Fenernan, S. (ed.) Emotion in Organisations, London and New bury Past, CA: Sage Hearn, J. (1994) ‘Research in Men and Masculinities: Some Sociological Issues and Possibilities’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Sociology, 30, 1, pp. 47– 71 198 Class, Gender and the Family Business Hebert R.K. and Link, A. (1989) ‘In Search of the Meaning of Entrepreneurship’, in Small Business Economics, 1, 1 Hirschon, R. (1984) Women and Property: Women as Property, London: Croom Helm Hochschild, A. (1983) The Managed Heart: The Commercialisation of Human Feeling, Berkeley: University of California Press Hoel, B. (1982) ‘Contemporary Clothing “Sweatshops”: Asian Female Labour & Collective Organisation’, in West, J. (ed.) Work, Women and the Labour Market, London: Routledge Holcombe, L. (1983) Wives and Property, Toronto: University of Toronto Press Hollowell, P. (1982) Property and Social Relations, London: Heinemann Hughes, A. and Storey, J. (1994) Finance and the Small Firm, London: Routledge The Independent (1996) ‘Asians Emerge as the New Moneymakers’, 12 June, p. 3 Jacoby, R. (1994) ‘The Myth of Multi-culturalism’, New Left Review, 208, pp. 121– 6 Jones, T.P. (1976) The Third World Within: Asians in Britain, Manchester: Institute of Geographers Annual Conference Jones, T., McEvoy, D. and Battett, G. (1994) ‘Raising Capital for the Ethnic Minority Small Firm’, in Hughes, D. and Storey, D. (eds) Finance and the Small Firm, London: Routledge Kanter, R. (1977) Men and Women of the Corporation, New York: Basic Books Keat, R. and Abercrombie, N. (eds) (1991) Enterprise Culture, London: Routledge, Kennedy, C. (1980) The Entrepreneurs, Newbury: Scope Books Kerfoot, D. and Knights, D. (1996) ‘ “The Best is Yet to Come?”: The Quest for Embodiment in Managerial Work’, in Collinson, D. and Hearn, J. (eds) Men as Managers: Managers as Men, London: Sage Kerfoot, D. (2001) ‘The Organisation of Intimacy: Managerialism, Masculinity and the Masculine Subject’, in Whitehead, S.M. and Barrett, F.J. (eds), The Masculinities Reader, Oxford: Blackwell Kets de Vries, M.R.F. (1977) ‘The Entrepreneurial Personality: A. Person at the Crossroads’, Journal of Management Studies, 14 Kimmel, M. (1987) ‘The Contemporary Crisis of Masculinity in Historical Perspective’, in Brod, H. (ed.) The Making of Masculinities, London: Allen & Unwin Ledwick, S. and Colgan, S. (eds) (1996) Women in Organisations: Challenging Gender Politics, London: Macmillan Business Legge, K. (1987) ‘Women in Personnel Management: Uphill Climb or Downhill Slide’, in Spencer, S. and Podmore, D. (eds) In a Man’s World, London: Tavistock Publications Lessnoff, M.H. (1994) The Spirit of Capitalism and the Protestant Ethic Aldershot: Edward Elgar Light, I. (1984) ‘Immigrant and Ethnic Enterprise in North America’, Ethnic & Racial Studies, 7, 2 Light, I. and Bonacich, E. (1988) Immigrant Entrepreneurs, Korean in Los Angeles 1965–1982, Berkeley: University of California Lynn, R. (1974) The Entrepreneurs, London: Allen Unwin Mac an Ghaill, M. (1993) ‘Irish Masculinites and Sexualities in England: Social and Psychic Relations’. Working paper, University of Birmingham References 199 Mac an Ghaill, M. (1994) ‘The Making of Black Masculinities’, in Brod, H. and Kaufman, M. (eds) Theorising Masculinities, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Marceau, J. (1989) A Family Business? The Making of an International Elite, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Marcus, G.E. and Dobkin Hall, P. (1992) Lives in Trust, Boulder Co.: Westview Press Marshall, J. (1984) Women Managers Travellers in a Male World, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Mason, C. and Harrison, R. (1994) ‘Informal Venture Capital in the UK’, in Hughes, D. and Storey, J. (eds) Finance and the Small Firm, London: Routledge Middleton, C. (1979) ‘The Sexual Division of Labour in Feudal England’, New Left Review, pp. 113–14 Millett, K. (1977) Sexual Politics, London: Virago Modood, T. (1991) ‘The Indian Economic Success; A Challenge to Some Race Relations Assumptions’, Policy and Politics, 19, 3 Morokvasic, M. (1987) ‘Immigrants in the Parisian Garment Industry’, Work, Employment & Society, 4, 1 Morokvasic, M., Waldinger, R. and Phizacklea, A. (1990) ‘Business on the Ragged Edge’, in Waldinger, R. et al. (eds) Ethnic Entrepreneurs, London: Sage Mulholland, K. (1993) ‘The Marginalisation of Women and the Processes of Wealth Creation’, in Sinfield, A. (ed.) Poverty, Inequality and Justice, New Waverley Papers, University of Edinburgh Mulholland, K. (1996a) ‘Gender Power and Property Relations within Entrepreneurial Wealthy Families’, in Gender Work & Organisation, 3, 2, pp. 78– 102 Mulholland, K. (1996b) ‘Entrepreneurialism, Masculinities and the Self-Made Man’, in Collinson, D. and Hearn, J. (eds) Men as Managers: Managers and Men, London: Sage, pp. 123–49 Mulholland, K. (1997) ‘The Family Enterprise and Business Strategies’, Work, Employment and Society, 11, 4, pp. 685–711 Newby, H. et al. (1978) Property Paternalism & Power, London: Hutchinson Nichols, T. (ed.) (1980) Capital and Labour, London: Fontana Nock, S.C. (1998) Marriage in Men’s Lives, New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press Oakley, A. (1987) ‘Gender and Generation: The Life and Times of Adam and Eve’, in Allatt, P. et al. (eds) Women and the Life Cycle, London: Routledge O’Brien, M. (1981) The Politics of Reproduction, London: Routledge Ochberg, R. (1987) ‘The Male Career Code and the Ideology of Role’, in Brod, H. (ed.) The Making of Masculinities, London and Boston: Allen Unwin, pp. 193–210 Pahl, J. (1980) ‘Patterns of Money Management within Marriage’, Journal of Social Policy, 9, 3, pp. 313–35 Pahl, J. (1983) ‘The Allocation of Money and the Structuring of Inequality within Marriage’, The Sociological Review, 31, pp. 237–59 Pahl, J.M. and Pahl, R.E. (1971) Manages and their Wives, Harmondsworth: Penguin Pateman, C. (1988) ‘The Sexual Contract, Cambridge: Polity Press Peach, C., Robinson, V. and Smith, S. (eds) (1981) Ethnic Segregation in Cities, London: Croom Helm 200 Class, Gender and the Family Business Penrose, E. (1980) The Theory of Growth of the Firm, Oxford: Basil Blackwell Pettigrew, A. (1979) ‘On Studying Organisational Cultures’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 4 Phizacklea, A. (1988) ‘Entrepreneurship, Ethnicity & Gender’, in Westwood, S. (ed.) Enterprising Women, London: Routledge Phizacklea, A. (1990) Unpacking the Fashion Industry, London: Routledge Phizacklea, A. and Ram, M. (1996) ‘Being Your Own Boss: Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurs in Comparative Perspective’, Work, Employment & Society, 10, 2, pp. 319–39 Pinchbeck, I. (1981) Women in the Industrial Revolution, London: Virago Pollert, A. (1981) Girls, Wives, Factory Lives, London: Macmillan Rainbird, H. (1991) ‘The Self-Employed: Small Entrepreneurs or Disguised Wage Labourers’, in Pollert, A. (ed.) Farewell to Flexibility, London: Routledge Rainnie, A. (1984) ‘Combined and Uneven Development in the Clothing Industry: The Effects of Competition on Accumulation’, Capital & Class, 22, 1 Ram, M. (1992) ‘Coping with Racism: Asian Employers in the Inner-City’, Work Employment & Society, 6, 4 Ram, M. (1994) Managing to Survive, Oxford: Blackwell Ram, M. and Deakins, D. (1996) ‘African-Carribeans in Business’, New Community, 22, 1, pp. 67–84 Reed, R. (1996) ‘Entrepreneurialism and Paternalism in Australian Management: A Gender Critique of the “Self-Made” Man’, in Collinson, D. and Hearn, J. (eds) Men as Managers: Managers and Men, London: Sage Roberts, J. and Coutts, A.J. (1992) ‘Feminisation and Professionalisation: A Review of an Emerging Literature on the Development of Accounting in the United Kingdom’, Accounting, Organisations and Society, 17, 3/4, pp. 379– 95 Roberts, I. and Holyroyd, G. (1992) ‘Structure and Sentiment: Family and Rationality Within the Capitalist Enterprise’, in Gilbert, N., Burrows, N. and Pollert, A. (eds) Fordism and Flexibility, London: Macmillan, pp. 154–69 Robertson, H.M. (1959) ‘A Criticism of Max Weber and His School’, in Green, R.W. (ed.) Protestantism and Capitalism: The Weber Thesis, Lexington, Mass: D.C. Heath & Co. Roper, M. (1994) Masculinity and the British Organisational Man, Oxford: Oxford University Press Roper, M. (1996) ‘Seduction and Succession: Circuits of Homosocial Desire in Management’, in Collinson, D. and Hearn, J. (eds) Men as Managers: Managers and Men, London: Sage, pp. 187–209 Rosaldo, M.Z. et al. (1974) Woman, Culture & Society, Stanford: Stanford University Press Rosener, J.B. (1990) ‘Ways Women Lead’, Harvard Business Review, November–December, pp. 120–5 Roy, A. (1990) ‘The Quiet Millionaires’, Daily Telegraph, Weekend Magazine, 25 August Rubeinstein, W.D. (1990) Men of Property, London: Croom Helm Sacks, K. (1974) ‘Engels Revisited: Women the Organisation of Production & Private Property’, in Rosaldo, M.Z. et al. (eds) Woman, Culture & Society, Stanford: Stanford University Press References 201 Savage, M. (1992) ‘Women’s Expertise, Men’s Authority: Gendered Organisation and the Contemporary Middle Class’, in Savage, M. and Witz, A. (eds) Gender and Bureaucracy: The Sociological Review, Oxford: Blackwell Scase, R. and Goffee, R. (1982) The Entrepreneurial Middle Class, London: Croom Helm Scase, R. and Goffee, R. (1989) Reluctant Managers: Their Work and Lifestyles, London: Unwin Hyman Scott, J. (1994) Poverty and Wealth: Citizenship, Deprivation and Privilege, London: Longman Scott, J. (1994) Privilege, Poverty and Wealth in Britain, London: Harlow Scott, J. and Griff, C. (1984) Directors of Industry, Cambridge: Polity Scully, J. (1994) ‘The Irish Diaspora Bar Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Study Between Birmingham, England and Chicago, USA’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Warwick Segal, L. (1990) Slow Motion: Changing Masculinities Changing Men, London: Virago Seidler, V.J. (1989) Rediscovering Masculinity: Reason, Language and Sexuality, London: Routledge Sennett, R. and Cobb, J. (1977) The Hidden Injuries of Class, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Sherrod, D. (1987) ‘The Bonds of Men: Problems and Possibilities in Close Male Relationships’, in Brod, H. (ed.) The Making of Masculinities, London: Allen Unwin, pp. 213–40 Sills, A., Tarpey, M. and Golding, P. (1983/84) New Community, 11, pp. 34– 41 Siltanen, J. and Stanworth, M. (1984) Women in the Public Sphere, London: Hutchinson Skeel, S. (1990) ‘Asian Majors’, Management Today, September Spencer, S. and Podmore, D. (eds) (1987) In a Man’s World, London: Tavistock Publications Storey, D. (1994) Understanding The Small Business Sector, London: Routledge Strauss, A. (1987) Qualitative Analysis for Social Science, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press The Sunday Times (1991, 2003) Book of the Rich, London: Weidenfeld Thirsk, J. (1976) ‘The European Debate on Customs of Inheritance, 1500–1700’, in Goody, J., Thirsk, J. and Thompson, E.P. (eds) Family and Inheritance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Thompson, E.P. (1976) ‘The Grid of Inheritance: A Comment’, in Goody, J. Thirsk, J. and Thompson, E.P. (eds) Family and Inheritance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Thompson E.P. and Goody. J. (eds) Family and Inheritance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Thomson, R. (1994) ‘Retailer out of City fashion’, Independent on Sunday, 6 November Twaddle, M. (1990) ‘East African Asians through a Hundred Years’, in Clark, C., Peach, C. and Vertovec, S. (eds) South Asians Overseas, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Veblen, T. (1949) Theory of the Leisure Class, London: Allen & Unwin Wajcman, J. (1998) Managing Like a Man: Women and Men in Corporate Management, Cambridge: Polity 202 Class, Gender and the Family Business Walby, S. (1986) Patriarchy at Work, Cambridge: Polity Press Walby, S. (1997) Gender Transformations, London: Routledge Waldinger, R. (1984) ‘Immigrant Enterprise & The Structure of the Labour Market’, in Finnegan, R., Gallie, D. and Roberts, B. (eds) New Approaches to Economic Life, Manchester: Manchester University Press & ESRC Waldinger, R., Aldrich, H. and Ward, R. (1990) ‘Opportunities, Group Characteristics & Strategies’, Ethnic Entrepreneurs, London: Sage, pp. 13–48 Ward, R. (1991) Economic Development and Ethnic Business’, in Curran, J. and Blackburn, R. (eds) Paths to Enterprise, London: Routledge Ward, R. and Jenkins, R. (1984) Ethnic Communities In Business, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Weber, M. (1958) The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Scribner, New York Wedgewood, J. (1929) The Economics of Inheritance, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Weick, K.E. (1985) ‘The Significance of Corporate Culture’, in Frost, J.P. et al. (eds) Organisational Culture, London: Sage Werbner, P. (1984) ‘Business on Trust: Pakistani Entrepreneurship in the Manchester Garment Trade’, in Ward, R. and Jenkins, R. (eds), Ethnic Communities in Business, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Werbner, P. (1990) The Migration Process: Capital, Gifts and Offerings Amongst British Pakistanis, Berg: New York West, J. (ed.) (1982) Work, Women and the Labour Market, London: Routledge Westwood, S. (1984) All Day, Every Day, London: Pluto Press Westwood, S. and Bhachu, P. (1988) Enterprising Women, London: Routledge Whitehead, A. (1984) ‘Women And Men: Kinship And Property’, in Hirshon, R. (ed.) Women & Property: Women as Property, London: Croom Helm, pp. 176–92 Whitehead, S.M. and Barrett, F.J. (eds) (2001) The Masculinities Reader, Oxford: Blackwell Wilkin, P. (1979) Entrepreneurship: A Comparative Historical Study, Norwood: Ablex Willis, P. (1977) Learning to Labour, Aldershot: Ashgate Wilson, P. (1983/84) ‘Ethnic Minority Business and Bank Finance’, New Community, 11, pp. 63–73 Witz, A. (1992) Professions and Patriarchy, London: Routledge Yancey, W.L. et al. (1976) ‘Emergent Ethnicity: A Review and Reformation’, American Sociological Review, 41 Name Index Aldrich, H. et al., 151, 153, 178 Allen, S., 6 Allen, S. and Truman, C., 28, 131 Anwar, M., 153, 158, 178 Barrett, M. and McIntosh, M., 45 Becker, G., 4, 50, 58 Boissevain, J., 8, 152, 158, 174, 186, 188 Bonacich, E., 156, 162, 178 Bonacich, E. and Modell, J., 151, 152, 178 Bourdieu, P., 7, 21, 22, 23, 46, 152, 173, 185 Brod, H., 21, 24, 26 Brod, H. and Kaufman, M., 106, 184, 187 Bun, C. K. and Hui, O. J., 153–4, 156, 162, 184 Burke’s Peerage, 14 Burt, R., 26, 92, 123, 152, 158, 174–5, 186, 188 Business Week, 15 Chell, E., 16, 90 Clark, C. et al., 153–4, 156 Clemenson, H., 36, 46, 71 Cockburn, C., 15, 50 Cohen, A., 173 Collinson, D., 92, 97, 119 Collinson, D. and Hearn, J., 21, 23, 66, 92 Connell, R. W., 116 Cooper, J. P., 87 Coyle, A., 49, 67, 182 Dahya, B., 175 Davidoff, L. and Hall, C., 5, 17, 26, 36, 46, 90, 103, 112 Davidson, M., 49, 182 Delphy, C., 70 Delphy, C. and Leonard, D., 60, 113 Doomsday Book, 14 Drucker, P., 90 Elson, D. and Pearson, R., 15 Engels, F., 21, 70, 113, 184 Erikson, A. L., 73, 86, 87, 113, 128 Felstead, A., 45 Finch, J., 69, 112 Fineman, S., 114 Fromm, E., 106 Ghillone, B., 68 Glaser, B. and Strauss, R., 17 Goffee, R. and Scase, R., 5, 83, 131 Goody, J., 73, 87 Goransson, A., 36, 46 Grant, J. and Porter, P., 49, 54, 182 Hammond, D. and Jablow, A., 24 Harding, S., 17 Hartmann, H., 21, 60, 180 Harvey Jones, J., 110 Heaney, S., 24 Hearn, J., 23, 90, 91, 94, 100, 114, 184 Hebert, R. K. and Link, A., 15, 90 Hochschild, A., 128 Hoel, B., 153, 178 Holcombe, L., 22, 69 Jones, T. P., 178, 185, 188 Joseph, Sir Keith, 15 Kanter, R., 66, 68, 69, 112, 115 Kelly’s directories, 14 Kennedy, C., 15, 91 Kerfoot, D. and Knights, D., 93 Kets de Vrie, M. R. F., 15, 17 Kimmel, M., 24, 25 Lessnoff, M. H., 155 Lynn, R., 15 Mac an Ghail, M., 92 Marceau, J., 168 203 204 Name Index Marcus, G. E. and Dobkin Hall, P., 60 Middleton, C., 46, 63, 87 Morokvasic, M. et al., 153–4, 167, 178 Mulholland, K., 7, 16, 98, 132, 167 Oakley, A., 58 Ochberg, R., 5, 89, 90, 107, 111, 115, 127, 184 Pahl, J. M. and Pahl, R. E., 115 Pateman, C., 12, 21, 46, 69, 73, 113, 128, 180, 184 Penrose, E., 77, 108, 145, 166 Phizacklea, A., 153–4, 162, 167, 178 Scott, J., 2, 10 Scully, J., 153, 178 Segal, L., 125 Seilder, V. J., 25, 89, 184 Sennet, R. and Cobb, J., 94, 96, 97, 106, 120, 183 Sherrod, D., 25, 25, 106 The Sunday Times Book of the Rich, 10, 14 Tebbit, Norman, 15 Thirsk, J., 73 Thompson, 70, 71, 72, 81, 87, 172 Twaddle, C., 156 Veblen, T., 60, 63, 103, 113 Rainbird, H., 178 Ram, M., 16, 17, 44, 55, 99, 154 Reed, R., 52 Roberts, I. and Holyroyd, G., 7, 152, 171–2, 186 Roberts, J. and Coutts, A. J., 50 Roper, M., 18, 89, 90, 97, 114, 115 Rosener, J. B., 149 Rubeinstein, W. D. 154–5 Savage, M., 49, 50, 182 Scase, R. and Goffee, R., 16, 90, 115, 119 Wajcman, J., 49, 65, 147 Walby, S., 21, 50, 180, 182 Waldinger, R., 153 Weber, M., 26 Wedgewood, J., 71, 187 Werbner, P., 8, 26, 151, 152, 153–4, 158, 163 Willis, P., 96 Witz, A., 50, 183 Who’s Who, 14 Yancey, W. L. et al., 174, 188 Subject Index accumulation strategies, 12 Anglo-Jews, 9, 156, 158 Asians, 9, 17, ch. 9 Beowulf, 24 beneficiaries, 72 career paths, 48–67 company man, 5, 77, 93–102, 166 coverture, 4, 20, 22 cyclical process, 5 de facto, 16, 55 dowry, 36 East African Asians, 9 emotional economy, 89–91 enclave economy, 151 England, 9 Enlightenment, 24 entrepreneurial ideologies, 5 entrepreneurial theory, 15–17 ethnic minority enterprise, 9, ch. 9 ethnic advantage, 154–6 family man, 117–29 father right, 21 female marginalisation, 60–7 flawed cultures, 154–5 freebench, 72 habitus, 7, 62 ‘hard wife’, 120 helpmeet, 17, 46, 48, 60 ideologies of domesticity, 4 idle wife, 55, 113 impartible inheritance, 70 Industrial Revolution, 24 Irish, 9, 156 laissez-faire, 25 Land Valuation Act 1911, 14 lineal preservation, 4 middle-class attributes, 162 Midlands, 9 ‘new’ business couples, 11–12 notion of wealth, 10 old business couples, 11–12 patriarchy, 2 primogeniture, 4, 8, 20, 22, 72, 81, 88 resources, 15 ‘self-made man’, 5, 15, 29 shared business culture, 7, 8, 152, 167, 174 social capital, 26 structural holes, 26, 123, 186 substantive rationality, 7, 152–3, 171–2 support, 46 systematic marginalisation, 3–5 takeover man, 5, 93, 102–9 transcendence, 4 wealth wealth wealth wealth 205 accumulation, 20 conservation, 20 creation, 20 preservation, 4