CHAPTER 9

The Chicano Movement/

The Movement of

Chicano Art

TOMAS YBARRA-FRAUSTO

orn in the rumu ltuous decade of the

1960s, Chicano art has been do~~ly

aligned with the political goals

of Chicano s truggles for selfdecermination. As an a~hetic credo, Chicano art seeks. to link lived

reality to the imagination. Going against mainstream cultural traditions of art as escape and commodiry, Chicano art intends that viewers

respond borh to the aesthetic object and to the social realicy reflected

in it...?\ prevalent attitude toward the art object is that it should provide..aesthetic pleasure while also serving to educate and edify. In its

various modalities, Chicano art is envisioned as a model for freedom,

a call to both conscience and consciousness. 1

B

PHASE I, 1965- 1975: CREATION OF THE PROJECT

Although struggles for social, political, and ecomomic equal.iry have

been a central tener of Chicano hisrory since 1848, the efforts to

unionize California farmworkers launched by Cesar Chavez in 1965

signaled a national mobilization, known as La Causa, among people

of Mexican descent in the United States. The Chicano movement, or El

Movimiento, was an ideological project closely aligned with the tactics, formulations, and beliefs of the civil-rights movement, the rise of

Black Power, the politica.1 agenda of the New Left, the onset of an

international student movement, and the struggles of liberation

throughout the Third World. Jn retrospect, the Chicano movement

was extremely hetemgcncous, cutting across social class and regional

and generational groupings.

Impelled by this mass political movement, Chicano artists, activistS, and intellectuals united to articulate the goals of a collective cultural pwject that would meld social practice and cultural production.

A primary aim of rhis project was to surmount straregics of containment by Struggling to achieve self-determination on both the social

and aesthetic planes. It was the Chicano movement-through va rious

political fronts such as the farmworkers' cause in California, urban

civil-rights activities, the rural-land-grant uprisings in New Mexico,

the student and antiwar ·movements on college campuses, the lobor

struggles of undocumented workers, and the rise of feminism- that

gave cogency to the cultural project.

Artists were integrated into the various political fronts of El Movimiento in unprecedented numbers and in signilic.1nt ways. They organized, wrote the poems and songs of struggle, coined and printed

the slogans, created the symbols, danced the ancient rituals, and

painted ardent images tha t fortified and decpeo~d understanding of

the social issues being debated in Chicano communities.

An urgeot first task was to repudiate exremal visions and desrroy

entrenched literary and visual representations thac focused on Mexican Americans as receptors rather than active generators of culture.

For rhc creative artist, whether painter, dancer, musician, or writer,

this meanc appropriation of his or her own self. Novelist Tomas Ri' 'cra funher definrs the enterprise:

The invention o( ourselves by oursdves is in aauaJity 2n extension of

our will. Thus, as the 0-ic.ano invents himsel£ he is complcnu:ncing

his will. Anorher con1plemcnt. 1"hi$ is of gr~ac importance bttause

these lives art trying to 6nd fonn. This devtlopmcnc is becoming a

unifying consdousnt."SS. The rhoughts o( the Chictano arc beginning

to constindy gyrate over his own life_ over his own development,

over his idenuty, and as such O\'t r hi5 own coNcrvarion. ... Chicano

literature has a triple mission: to represent, and ro con.serve that

asptt1 of life that the Mcxiun American holds as his own and at the

same time destroy the invention by others of his own life. Th:at

is-conservation, struggle and invcnrion.l

This triad of conservation, struggle, and invention became a theme of

Chicano literature. It served also as a core assumption in the production of energetic new forms of visual culture.

llO

TO M AS YBARRA - FRAUSTO

Sustained polemics by artists' groups rhroughout the country es·

tablished rhe forms and content of Chicano art: Though few collective

n1anifestos \Vere issued, aesthetic guideJ ines ca·n be gleaned from artists' statements, comn1uniry-ne,vspaper accounts, and oral inrerviews.

Typical of this florescence of socially engaged artistic consciousness

was rhe formation of the Mala Efe group (Mexican American Liberation Arr Front) in the San Francisco Bay area. The artist Esteban Villa

recalls:

&to fue por tso de/ ano '68... . E•a l.i <poca de/ grape boycott y de/

Third World Strike en Berkeley. We would meet regularly to discuss

the role and function of the artist in El Movimiento. At first our

group

w3$

co mp0sed mainly of painters and we \o;ould bring our

work and criticite it . Discussions were heated; cspecialJy the polemicc on the form ~nd content of revolution~ry

11n ('l.nd

the r~lev'1nee o(

murals and graphjc an-. Posters and orher forms of graphics ""'ere

espe<:ially discussed since many of us were creating c.artelones as

organizing tools for the various Chicaco ntitotes (spontancou.s "hap·

penings"] in the Bay Area.

Our group kept gro,ving and S()On included local p0ets ar:d

intellectuals like Octavio Romano. Jn March of 19691 we deci-ded ro

hold an exhibition in a big old frame house on 24th Street here in

Oakland. The spacious bur slighdy ra•quache house had been christened L1 Caus.a. llte exhibitjon \\•as called Nuevos Sintbolos for la

Nucva Raza and atte1npted to visualli' project i1nages of el hon1brt

nuevo; the Chicano who had emerged from lhe decolonization pro·

cess.

Opening nighr was a todo dar wi:h viejitos. 1u:iinitos, and vatos

de la cal/e walking in, checking it out and staying ro rap. Afgunos

poetas locales read their \Vork and rhtre was music and pldtica 1nuy

sabrosa. We all sensed the begjnniog C1f an artistic rcbirrh. Utt uuevo

art< de/ p1teblo.>

This "nuevo arte del pueblo" (a new art of the people) was to be

created from .shared cxpcr-icncc and ba_~cd on communal art tcaditions.

Necessarily, a first srep was ro investigate, and give autbority ro, au·

thenric expressive forms arising within the heterogeneous Chicano

con1munity. Jn opposition to the hierarchical dominant culture, which

implicitly made a distinction bet\veen Hfine art" and "folk art," at·

tenipts \\ cre made to eradicate boundaries and integrate categodes.

An inirial recognition was that the practices of daily life and the lived

environment were pri1nary conscituen: elements of the oe\v aesrhedc.

In the everyday life of rhe barrio, arr objects are embedded in a

1

Chfcano Movement/Chicano Art

I3 I

network of cultural sites, activit cs, and events. "'The way folk an firs

into this cultural constellation reveals tin1e~tested aesthetic practices

for accompl ishing goals in social, religious and economic life. And

these practices are on·gomg; they point no1 to an absolute standard or

set of truths. '' 4 Inside the hon1e in the yard, and on the s-treet corncrthroughout the barrio environ1nent-a visual culture of accumulation

and bold display is enunciated. Handcrafted and store·bough1 items

from tbe popular culture of Mexico and the mass culture of the United

States mix freely and exuberantly in a milieu of inventive appropria·

cion and reconcextualizatioo. The barrio environment is shaped in

ways that express the communitr's sense of itself, the aesthetic display

projecting a sort of visual bicult'Jralism.

As communal customs, ri1uals, and traditions were appropriated

by Movimiento artists, they yielded boundless sources of imagery. The

aim was not simply to reclaim vcrna~ lar u:aditj,9ns but ro rcinccrpret

them in ways useful to the sOclal urgency nf th.e pcriOd-: ....

1

Some Vernacular Sources of Chfoano Art

ALMANAQU&S Al1nanaq·ues {caltndars} arc a commnn fP=atutC' in Chicano households, given to favored customers each year by barrio businesses. Almanaques cradition30y feature images from Mexican

folklore. Favorite images include nostalgic rural landscapes, intcrpre·

tations of indigenous myths or hi>torical events, bullfighting and cock·

lighting scenes, and the full pantheon of Catholic S3ints. Two of rhe

most common images from the a.'manaque tradition are the Virgi11 of

Guadalupe and an Aztec warrior carrying a sleeping maiden, which is

a representation of ihe ancient myth of lxtacihuatl and Popoca1eped

(two snow-covered volcanoes in :he Valley of Mexico}.

Almanaques are printed in the United Srotes, but the lithographed

or chromolithographed images are generally imported from Mexico

because of the immense popularily of famous almanaque artists such

as Jesus Helguera and Eduardo Catano.5 Their pastel, romanticized

versions of Mexican types and customs are saved from year to year

and proudly displayed in homes.

In tbe almanaque tradition, many community centers began issuing ea/endarios Chieanos in the roid-1970s.

BSTAMPAS R!UCIOSAS

In mony Chicano households, images of

Carbolic saints, martyrs of the fai1h, and holy personages are mingled

with family photographs and memorabilia and prominently displayed

on home alurs or used as wall d<eorations.

132

TOMAS YBARRA -FRAUSTO

Dispensed at cburches or purchastd in religious-sp«ialty stores,

the estampas religiosas (religious images) vary from calling-card-size

to poster-size. Es14mpas represent Catho~c saints with their rraditional symbols: for example, St. Peter with a set of two crossed keys,

St. Clement with an anchor, o r St. Catherine with a wheel. The images

are folk religious nacratives, depicting miracles, feats of manyrdom in

defense of the faith, o r significant stories from the lives of the saints.

Parents refer to the es14mpas as they rccount the heroic episodes depicted, both socializing their children and introducing them to the

tenets of the Catholic church. The saints of the est4mpas become

guides to proper behavior and are many a child's first encounter with

traditional Christian symbols.

ALTAR.ES

Artists also focused on alta1es (home religious shrines) as

expressive forms of culrural amalgamaiion. In their eclectic comporition, they fuse traditional items of folk material culrurc with artifaas

from mass culture. Typical consrituenn of an alt4r include crocheted

doilies and embroidered cloths, recuerdos (such as flowers or favors

saved from some dance o r parry), fomtly pho tographs, personal me·

menros, santos (religious chro molithogmphs o r starues) especially ven·

crated by the family, and many o ther demcnts. The grouping of the

various objects inn particular spacc--atop a television set, on a kitchen

counter, atop a bedroom d resser, o r in a specially constructed nicho

(wall shelf)-appcars to be random but usually responds to a con·

scious sensibility and aesthetic judgment of what things bdong together nnd in what arrangement. A/tarts arc organic and ever·

changing. They arc iconic representations of the power of

relationships, tbe place o f contact between the human and the divine.

A/rares arc n sophisticated form of vcrnocular bricolage, and thtir

constituent clements can be used in an infinite number of improvised

combinations 10 generate new meanings. A number of Chicano anists,

among them Amalia Mesa-Bains and Rene Yanez, became k nown as

altaristas (makers of altars ), experimenting with the altar form in

innovative ways.

Mexican carte/es (t'heatrical posters) and the ubiquitous

commercially designed advcrtiscmcntS fo r barrio social events, such as

CARTEL.es

dances or ardstic carav:ins o( visiting Mexican entertainers, were also

significant image sources.

Chicano youth cultures

were acknowledged as guardiaru and generators of a sryle, stance, and

visual disroursc of pride and identity. Urban iconography melds cus·

toms, symbols, and forms of daily-hfe practices m the metropolis.

Pia= (graffiu), ranoos, cunomiud rtllr/las (low-rider cars), gang reg;aha, and countless other expressive forms evoke and embody a con·

temporary barrio sensibility. h is a sense of being that 1s defiant,

proud, and rooted in ruuuocc. G1lbcn Lujan, Willle H<.rron, John

Valada, Judith Baca, and Santos Maninn are among legions of a.n ·

ists who expenment wnh barrio symbology in their work.

EXPUSS!n FORMS FttOM YOU'Tlt CULT\IRES

Rasquachismo: A Chica1tO Sauibthty

Beyond grounding themselves in vernacular art forms, Movimiento

anins found strength from and recovered meaning sedimented in con·

sistent group stances such as r~111Jchismo. ROJq11achismo' IS neither

an ioo nor a style, but more of a pervasive attitude or taste. Very

gencully, rasquachismo 1s an underdog perspective-a view from los

de abo,o. h IS a saoa rooted in resourcdulncss and adaptability, yet

ever rrundful of aesth<ucs.

In an environment 1n which things are always on the edge of

coming apart (the car, the 1ob, the toilet), hves arc held together wirh

spn, gnt, and mOl!tdas. Movulas au whatever coping sttatcgics one

uses to gain umc, to make opuons, to retain hope. Rasquachmno ts a

compendium of all the movidas deployed in immediate, day· to·day

bv1ng. Rcstl1enet" and resourc.,fulncss spring from making do with

what 1s at band (haur r<ndrr w cous). ThlS uuhunon of available

resources makes for syncreus11, 1uxrapos111on, and mtcgrarion.

Rasquachismo 1s a scnJ1b1l11y anuncd 10 mixtures and conOuence.

Commuruon ts prdcrrcd over purity.

l'lllbng through and mak111gdo arc not cuar•nrors of sttunry, «>

things that arc ra$q111Jtht possess an ephemeral quality, a sense of

tcmporality and impermanence-here today and gone tomorrow.

Wh1k things might be crc.ied wing wh•tcver IS at hand, auennon IS

always given 10 nuaDCl'S and dcmls. Appeaunet" and form have pre·

«<kn~ over Euncuon.

In the realm o( taste, to be ra$q11acht is to be unfettered and

unrestr~tncd, 10 bvor the clabontt over the s.mple, the Oamboyant

over the severe. Bright colors (ch11/antts) ore preferred to somber, hrgh

1ntcns1ry to low, the shimmering and sporkling over the murcd and

l:M

TOMAS YIARRA · fRA USTO

subdutd. The ratqtc1c.be 1nd1n•11on ptla p•ttem on 112nem, filling oil

ova1lable spaa wuh bold d1spl•y. Om•meniation and clabor.mon

pren1l and arc joined wi1h a del1gh1 m texture and sensuous surfaCtl.

A work of an may be rasquach• 1n multiple and complex ways. h can

be sincere and pay homage to 1hc scnsibiliry by rcsiaring i1s premises,

1.c., the underdog woridv1ew actualiud rhrough language and behav·

ior, as m the dramaric prcsenianon I.a Carpa de los Rsltquachu, by

uus Valda. Another stntegy is for the anworlt to evoke • ratquacht

sens1b1hty through sdf-<>OnScious manipulation of matcnals or iconog·

rapby. One thinks of the combination of found mattri•ls and the use

of satiric wit in the SC11lpNrcs of Ruben Trcjo, or rhe manipulauon of

rilJquacht artifacu, code$, and $ensib1liria from boch sides of the

border m the performance pieces of Guillermo Gomcz·~na. Many

Chicano anisis conrinue 10 1nves11ga1e and interpret faccis of ratqua·

ch1smo as a conaptual lifesryle or oes1heric str:uegy.

Fronll of Stn1ggk, Forms of Art

The tn1nal phase: of the Oucanocultural project (circa the m1d·l960s)

was seminal in validating cmanapato<y communal pracoc:es •nd cod·

rfying the symbols and images that would be forcefully deployed 1n

advcnuial rouoternprcsenmions. By that rime, visual anuis had

been well inrcgraced inro the various political fronrs of El Mov1micn10,

within which they were gestating a Chicano an movement that was

narional in scope and developed outside the dominan1 museum, gal·

lery, and ans·publicarion circuit. Fluid and tendentious, 1hc an produced by dUs rnovcmcnr undcrta>rcd public connection instead of

private cognition.

Inscribed in multiple arenas of agi121ioo, artists continued to

evolve '"' arU de/ pud>lo thar aimed 10 ~the gap bctwttn radial

politics and community-based culcural practices. The rural farmwork·

ers' cause and the urban srudcn1 movement arc prime examples of this

rapprochement.

La Causa, the farmworkers' srruggle, was a grass-rno1s uprising

lha1 provided the infinitely complex human essence necessary for ere·

ating a true people's an. One of the early purveyors of campuino

cxpreuion was the newspaper El Makriado (The Ill-Bred). futablisbcd primarily as a cool for organizing, the pcriodial soon amc to

funcuon as a vdllc:lc that promoted untty by messing a sense of class

consooumcss while building cultural and political awareness. In at•

rime terms, El Malcriado lived up ro its name by focusing on an fomu

Chicano Movement/Chicano An

135

ou1side 1he "high-3rt" canon, such as carica1ure and cartoons. T he

pervasive nesthctic norm was rasquaehis,no, a bnwdy, irreverent, sn·

tiric-, and ironic worldview.

In California, among 1he firs1 expressions of this rasquac/Je art

were the poli1ical drawings of Andy armano, which were reproduced

in El Macriado Starting in 1965. Wi1h trenchant wi1, Zermano crea1ed

Don Sotaco, a symbolic representation of the underdog. Don So1aco is

the archerypal rasquache, the dirt-poor but cunning individual who

derides authority and oursmarts officialdom. ln his cuningly satirical

cartoons, Z ermano crea1ed vivid vignenes that are a po1ent expression

of campesinos' plight. His drawings clearly poin1 out 1he inequalities

cx:isting in 1he world of the patron (the boss) and 1he agricultural

worker. To a great extent, these graphic illustrations of social relations

did much to awaken consciousness. With antecedents in rhe Mexican

graphic tradition of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Jose Clemente

Oro~co, the vivid imagery of Andy Zermano documents the creation

of art for a cause.

The farmworkers' journal E/ Malcriado was also signi6canr in its

efforts to introduce Chicanos to a full spectrum of Mexican popular

art. lrs pages were full ol people's corridos (ballads), poems, and

drawings. hs covers often reproduced images garnered from 1he var·

ious publications of the Taller de Gra6ca Popular (Workshop for Popula r Graphic Art), an imponant source of Mexican political art.

Through this journalistic forum, Chicano artists became acquainted

with the notion that an of high aesthetic qualiry could substanrially

aid in furthering Chicano agrarian struggles.

As a primary impetus toward collaboration between workers and

artists, E/ Ma/criado planred the seed thar would come ro fruition in

many other cooperative ventures between artists and workers. The

creative capacities of artists were placed at the service of and wel·

camed by those struggling for justice and progress.

Simulrnoeously with the culrural expression of the farmworker's

cause, a highly vocal and visible Chicano siudent movement emerged

during rhe mid-1960s. Related to the worldwide radicalization of

youth and inspi.red by in1ernational liberation movements, especially

th.e Cuban revolution, the Black Power movemenr, and varied domes·

tic struggles, the Chicano siudent movement developed strategies to

overcome entrenched patterns of miseducation. lnsdtutionaliz.cd rac-

ism was targeted as a key detriment, and culiural affirmation lune·

tioned as an important basis for political organization.

Chicano culture was affirmed as a creative, hybrid reality synthe·

136

T O MA S Y BARRA-FRAUSTO

sizing elements from Mexican culture and the social dynamics of life

experience in <he Uni<ed Sta<es. Scholars such as Octavio Romano

published significant essays debunking orthodox views of Chicano life

as monoli<hic and ahiswrical. Contrary to these official notions, Chi·

c:ino culture was affirmed as dynamic, historical, and anchored in

working-class consciousness.

Within the student movement, art was assigned a key role as a

maintainer of human signification and as a powerful medium <hat

could rouse consciousness. Remaining outside the official cultural ap·

paratus, the student groups originated alternative circuits for dissem·

inating an outpouring of artistic production. As in the nineteenth

century, when Spanish-language newspapers became major ouders for

cultural expression in the Southwest, contemporary journals func·

rioncd as purveyors of cultural polemics and new representations.

Although varying in emphasis and quality, most srudenr-movemcnt

periodicals shared a conscious focus on the visual arts as essential

ingrediems in the formation of Chicano pride and iden1iry. For many

readers, it was a first encounter with the works of the Mexican mu·

ralists, the graphic mastery of Jose Guadalupe Posada, the Taller de

Grafica Popular, and reproductions of pre-Columbian artifacts.

Equally imponanr, Movimicnto newspapers such as Bron~, £/ Ma·

chttt, £/ Popo, Chica>1ismo, and numerous others published interviews with local Chicano artists while encouraging and reproducing

their work.

Knowledge about the Hispanic-Native American art forms of the

Southwest came lrom neither 11cademic nor scholarly sources, but

rather from venues within the movement such as £/ Crito de/ Norte,

a newspaper issued from Espanola, New Mexico, s1ar1ing in 1968.

This journal had a grass-roots orientation and placed emphasis on

preserving the culture or the rural agrarian class. Often, photographic

essays focusing on local arrisans or documenring traditional ways or

life in the isolated pueblitos of northern New Mexico were featured.

Clcofas Vigil, a practicing santero (carver of samos) lrom the region,

traveled widely, speaking to groups of artists. The carvers Patrocinio

Barela, Celso V..Uegos, and Jorge Lopez, all master santeros who were

collected, documented, and exhibited by Anglo patrons during the first

part or the century, gained renewed influence wirhin the budding as·

sociations of Chicano artists. Old and tattered exhibirion catalogues,

newspaper clippings, and barely legible magazine articles that docu·

mented their work were examined and passed from hand to hand to be

eagerly scrutinized and savored. Primarily through oral rradicion and

Cllicaoo~ht

137

rhc informal sharing of visual documcntarion, Chicano amst.S became

awan: of a m•JOr ancestral folk an tradition. And aside from the

Movim1ento pres$, literary and scholarly JOurnals such as El Cnto and

RtvistlJ Chiuma Riquoia often published ponfol1os of arust.S' works.

All these alrcmauvc venues rn><ned an into life, propagaung enabling

visions of Chicano cxpcncncc.

Asserting that Chicano an had a basic aim to document, denounce, and delight, ind1Y1dual anms and anms' groups resisted the

formula1ion of a restricted acsthcuc program to be followed uniiormly.

The Chicano community was hetrrogcncous, and the an formt 11

inspired were equally vaned. Although rcprcscntanonal modes became dominant, some artists opted for abstract and more personal

cxprcn1on. An1s1s 1n th11 groop felt tliai internal and tub1cruvc .,cws

of tc11l11y were sign16can1, and that formal and technical methods of

presentation should remain var1cd.

Al1er11a11ve V1s1ons and Stru<turts

By the early 1970s, Chicano 1n1ru had bandcd together to crute

nerworkJ of information, murual support systems, and altcrnanvc an

arams. Regional amns" groupt such as the Royal Chteano Air Force

(R.C.A.F.) in Sacramento, the Rna Art and Media Collective m Ann

Arbor, Michigan, me Mov1m1cnto Amsuco Chicano (MARCH) 1n

Chicago, the Con Safos group 1n San Antonio, Texas, and many others

persisted m the vn•I ta5k of creaung art forms that strengthened the

will and fonificd the cultunil idcnmy of the commun11y.

With militant and provocauve stnttcgics, Chicano am organiutions developed and sharcd their art within a broad community context. They brought aesthetic plcuurc to the son of working people

who walk or take the bus to work in rhe factot1es or m rhe scrvrce

sector of the urban metropolis. In its collcruve chanicter, tn rts sustained cffons to change the mode of part1op211on bcr..un amsrs ind

their public, and, above all, as a vehicle for sens11mng communiucs to

• pluralistic rather man a rnonohthtc acsthcttC, the Chia no altemauvc

arr circu11 played a central and commanding role tn nununng a visual

sensibility in the barrio.

POSTERS The combauve phase of El Mov1miento called for a m1hram

an useful in the mobilization of large groupt for polmcal acr1on.

Posters were sttn as accessible and expedient sources of visual informacion and indocrrinat1on. Bccaust they w~ 1ncxpens1vt co repro-

138

TOMAS YBARRA-FRAUSTO

duct and portable, they wttt well suited for mass distnbution. Monover, posters had historical antettdcnts in the O,icano comm1101ty.'

Many of the famous plants or political programs of the pan had bttn

im1ed as broadsides or posters to be affixed on walls, informing the

populoce and mustering them for political action.

The initial phase of Chicano poster production was directly in·

Oucnccd by both the work of Jose Guadalupe Posada and images from

the Agustin Casasola photographic archives, which contained photos

documentang th< Mexican rtvolution.1 Early Chicano poster makers

appropriated images from tncsc tw0 primary SOW(IC$ and mncly reproduced and masSJvely d1smbuted Posada and Causal• 1magc1 cm·

bellished with sl~ns such as Vivo Lo Causa ind V""' Lo R<V0luc16n.

Francisco "Pancho" Villa ond Emiliano Z;apara, 1coruc symbols of the

Mexican Revolution, were among the fim images that asuultcd C111·

cono consciousness via the poster. Poster images of Villa and Zapata

were onached to crude wooden planks and carried in picket lln1e1 and

countless demonmations. Quo1ing from Mexican antecedents was an

important 1nmal strategy ol Chicano an. Having established a cultural

and visual continuum across borders. 0.1cano artists could then mo•·e

forward co forge a visual voabulary and expressive forms correspond·

mg to a complex b1culrural ruhry.

Used to announ<r rallies, promote cultural ~11, or simply as

visual •tatemenrs, Chicano posters evolved as forms ol communica·

tion with memorable imagery and pointed messages. "lhe superb

crafrsmnnship ol artists such as Carlos Cortes, Amado Murillo Pena,

Rupert Carcia, Molaquiu Montoya, Ralph Maradiaga, Linda Lucero,

Ester Hernande~ and• host of 01hrrs drvatcd th< poster from a mere

purveyor of faru into visual 51a1emcnts that delighted as well as tn·

formed and Slimulated. Formal clrmcnlS such as color, c:omposmon,

and lrtt<nng style echoed divt~ graphic traditions: the po,,.·erful,

socially conscious graphics ol the Taller de Cralica Popular 1n Mexico,

the colorful, psychtdrhc rock·posttr art of the hippie coun1crcul1urt,

and th< boldly asscnivc styl< of th< Cuban offrche.

Such eclectic design sources caught graphic artists how 10 apJ)<'al

nnd communicart with brevity, emphasis, and force. Chicano posrcn

did nor create a new visual vocabulary, but brilli_trul~ united various

stylistic inOucnces into an emphu1c hybrid expression. Tht rwo salient

curgories arc political posters and event posters. Tht pnmary lune·

uon of both forms was ideological mobilization through vuual and

verbal means.

o.c:ano Mo........ua.ano Art

t )9

Chicano posters generally were issued in 1'1and·silkscrcened edi·

tions of ~eral hundred or li1hographed runs of several 1housand.

They wuc posted on walls, distribu1cd free a1 ralhcs, or sold for

nominal prices. Within many sectors of the community, Chicano po>t·

ers were avidly collected and displayed m perso nal spaces as a matter

of pride and identificauon with their mcssoge. For a mass public un·

accustomed and little inclined 10 v1si1 museums and arc galleries, 1he

Chiaoo postu provided a direct connection tO the pleasures of own·

mg and responding 10 an arc object. Chicano posters were valued both

as records of historical events and as sausfying works of art.

MURAL$ The bamo mural movement is perhaps 1he most powerful

and enduring contnbuuon of the Chigno an movemem nationwide.

Created and nunured by the humanist ideals of Ch1c;ono struggles for

sclf·de1erm1naiion, murals functioned ns n pictorial renecuon of the

SOctol drama.

~aching back to the go•ls and dicta of 1he Mexican muralim,

csptt,.lly the pronoun«mcnts of David Alforo Siqueiros, m 1he mid·

1!160s Ch1ano anms called for an ut char was public, rnonumencal,

and accessible to the common people. The genera1ive force of Chicano

murahsm was also a man social movement, but the artim as a whole

did not hove the same kmd of formal training as 1he Mexican mural·

ms, and they fostered mural programs through an ohernarive ccrcuu

independent of of6aal sanmon and paironage.

For thear visual dialogue, muralists used themes, molifs, and icon·

ography tha1 gave ideological direction and visual coherence co the

mural programs. In the mJin, the amsuc vocabulary cenmed on 1hc

ind1g<nous hcnugc (especially the A11cc and Mayan pur), 1he Mex·

icon Revolunon and 1u epic heroes and heroin~. renderings of bo1h

hisiorical and coniemporary Chicnno socinl activism, nnd depictions

of everyday hfe in the barrio. lmernacionalism entered the pictorial

vocabulary of Chicano murals via iconographic references to libcra·

rion struggles in Vi.rnam, Afria, and Latin America and morifs from

culrurcs m 1hosc areas. The muralists' effons were persistently directed

toward documcntauon and denunciation.

Finding a visual language adcqu31c 10 depict the epic sw..,p of the

Chiano mo vemC1'1t was nor simple. Some murals became srymicd,

offuing romantic, archa1a11ng views of indigenous culture, uncri1i·

cally dcp1ctrng Chicano hfe, and poriraying cultural and historical

evcntS wirhour a clear poluical analyses. Successful murnl programs,

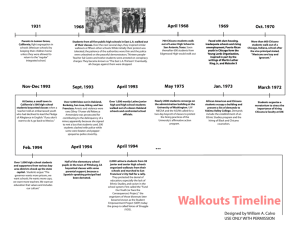

Fig. 9-1 . J.falaqul:u Afontrl'J'J., Vndocum<nlcd~

1981. Rtprodu<od by P<'"

m1isl0n o( thC" artist.

howc,·er, were most signi6cam in reclaiming history. As rhe commu·

nity read the visual chronicles, it imemalizcd an awareness of the pasr

and activated strategics for the future.

Apan from th~ aesthetic conte:nt, muralism \\'as signi6cant in

acrualiz.ing a communal approach to rhc production and disstminarion of art. Brig;idcs of 3I'tisrs and residents worked wirh a director

who solicited community input during the various stages of producing

the mural. Through such collaborative actions, murals became a largescale, comprehensive public-education system in the barrio.

In retrospect, it can ~ affirmed that Chicano art in the I 960s and

1970s encompused both a political posi11on and an aesthetic one.

Thal an underscored a consciousness dm helped define and shape

fluid and 1mrgrauve forms of visual culturo. Artisrs functioned as

visual educators, with the important task of refining and rransmiuing

1hrough plastic exprrss1on 1hc ideology of a rommunuy smY!ng for

sclf-de1crm ina1ion.

A Chicano na1ional consciousnes> wa> asserted by a rrva•·al 1n •II

1he ans. Aescheuc guidelines were noi offiaally promulga1ed bu1 arose

wirhm 1he aaual arena of pofirical practitt. As opposed 10 main·

stream art moverncrus, v.•here critical persixcti\'C') remain :11th~ IC'Vrl

of 1he work (an abou1 itself and for i1seff), che Chicano an movrmnt1

sough1 10 extend meaning beyond the aes1hetic obi= co include rrans·

forniation of the n1utcrial env1ronrnern as 'vell as of consc1ousncss.

PHASE 11, 1975-1990: NEUTRALIZATION AND RlCUPERATION OF

THE PROJECT

The lace 1970s and 1he 1980< have been a d)'narn1caff)' complex 1unc·

lure for 1hc Chicano culrural projec1. Many of II> posrul•1es ~nd aim>

have come 10 frumon during 1h1> nme. Three of 1hne aim> >re; I the

crcauon of a core of vi;ual >1gn1fieauon, n bnnk of >ymbol> and images

1ha1 encode 1he deep s1ruc1urcs of Chicano experience. Ou wing from

1h1s core of commonly undrrstood 1conoguphy, anim c•n cre.1<

142

TOMAS YBARRA-FRAUSTO

countcrrepr~rnt:irions

that ch3llcnge the in1poscd '"m3srcr narrarive"

o( clue 1Jrt practict"; ( 2) the mainccn3ncc of ahcrnanvc art srrucrure.s,

spac<s, and forms. For more rh•n rwo dccad<>, Chic•no •rrs org•ni·

zsnons have pct$•sred rn rhe orduous t•sk of crcoring • respQnsivc

working-class audience for :irt. A principal goal of th«• efforts has

bt'cn to mak• :irt acn'SSibl•, ro dtfl«1 its raufitd, diris1 •ur:i, •nd

csp<cially to reclaim rhe an from its commodiry srams wuh rhe ideal

of rrruming ii 10 a crirical role "~rhin rhe social practices of daily

living; 3Jld (3) th< cominu•rion of mural programs. Although there

has bten a diminucion in the numbor of public art fonns such as

murals and posttrs, whar has bttn produced since 1975 is of deeper

policical complcxiry and superior aesthetic qualiry.

According 10 the muralisr Judith Baca,

Loter works such as rhe Gr<>t Wall of Los Angeles dtvtlop<d • new

genre of murals which ha,·t: dOSc: 31Ji,ancc "'ith conceptual pc.rfor·

mancc 1n that the O\"C:rall mural rs only one pan or an overall pl3n to

aff<et soa•I change• .\iurahsrs such as ASCO [• ~rformanct groupl

bq;a.n co use thrmsclvn as tilt- an form. drCMtng che~lves like

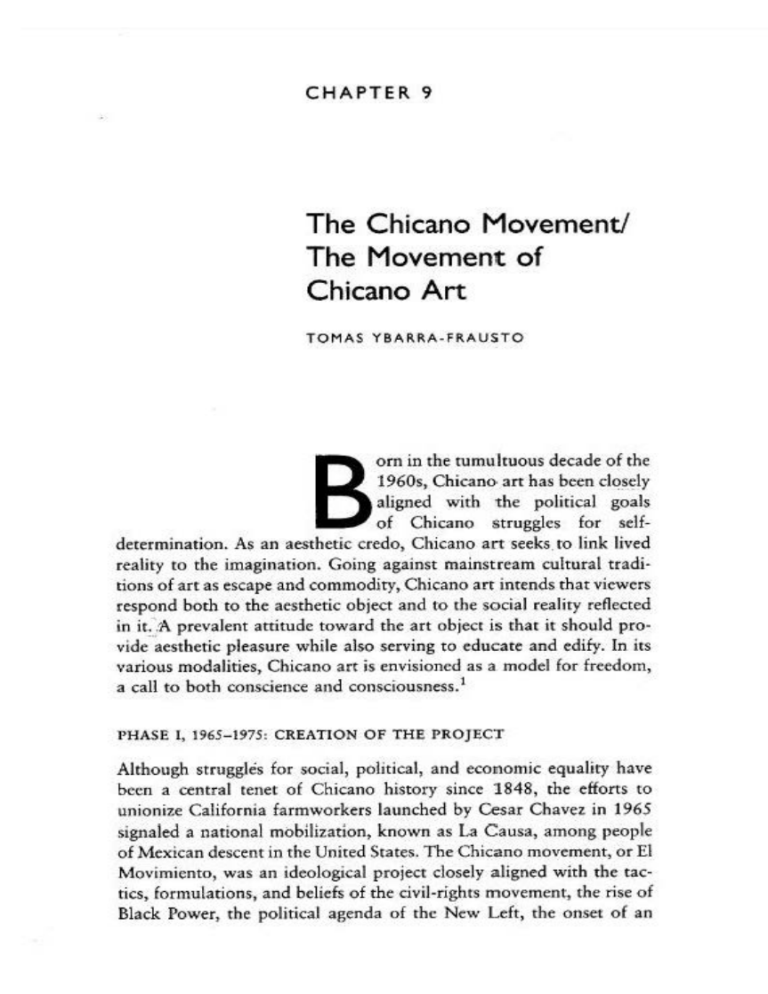

Fig. 9·l . 11.w,,.,,t CintM. Fot Catl~~f'PO fnd the ALB, 1911 RtpmJu<rd by pcrm1\•

of th.r ;utt~t.

MOn

..

· ---~,

F't'- 9~ D""4 A•..io..

El l':op>I, fugmmt of

l.ottt1i

(luan..1. l~tJ .

Rq>ro.t.....i " " ' ' o(

chc ilrU\I

mur.il1 and ~1rpp1ng JoVri·n off "'·.JU) to f'l":r(orm . Ex~nmnll Vrinh

ponahlc n1ur.1ls .1nd nrv.• Wt111I ron1rn1 ron1111ut". ThC'rr 1~.:. 1h1h of

inltrCM fro1n 1hc prmc~' co the prcxlui.:1. \t1h1lr (cY..tt mur.JI) iarr

qu.1111) .-nJ t~ lo-rm-. ol

hr \ 1('\\-rJ i.1<1 :an eJuc.iuonal pr<KC\~."'

bc111~ p.11n1N. C~) .arc- o f h11'h('r

mak1n~ e<HlltllUt' co

1m.a~·

1

Such •ccornphshrnent> .ur r.pcc1•lli• pr.mcwonhy, ha\lng tr•n

spired during • period or intCll>t chnngc nnd tramfor111Jtio11 111 Chi

cano communmcs. 'I he 111op1an buu•·ancy th•t >u>1•1ned • n•uon•l

Ch1cnno art movement has erud~-d. A• 1hc ground•wcll o( rnllecuve

pohucal ncrion hns disper.cd, as rnorc Ch1C3n<» enttr the prnfeu1on•l

111nh1l11y, .md •1 puhhc •rt

clus and arc affected hy us nnphcd

forms lrnve dimini>hcd 111 frcqucn<y, 1roc111i;• of J new agcnd• ol

muggl< ha.c surfaced.

Given dc111of1r>ph1c dota 111d1caiins 1hn1 1hc number ol people of

Latin American de>ccni 1n the Un11cJ Smn '' growing, •nd i:i•·•n

'°'"'

1-M

TOMAS YBARRA-FRAUSTO

I

+

Fog. 9-S. c.,.,,.,. Lomas G.,..., Una Tard< (On< Afternoon). R<produad by pcrmis·

"°" of the

i.rm1.

sociologic:il data ind1c;11ing 1ha1 Spanish·spcaking groups remain def·

ini1cly "01hd' for scvcral generations, new cultural undcrcurrenis

among Chicanos c;ill for an awareness of Amcnc::t as a coniincn1 and

no• a country. In the new typology an cmcrgen1 axis of influcnce migh1

lead from Los Angeles 10 Mexico City and from 1h<rc 10 Bogo1a, Lima,

Buenos Aires, Managua, Barcelona, and back 10 thc barrio. For the

creative anis1s, such new polmcal and acs1hcdc liliations expand the

field wi1h halluc1na1ory possibililies. As pcrformancc artis1 Guillcrmo

Gomtl·Ptna pointS ouc:

The Stttngch and onganahty O( Ch1a~UaUnO rontt"mporJry :irr 1n

the U.S. he> r•m•lly 1n 1hc faa 1ha1 II 15 of1cn bicuhur.I. bihngu.11

ondlor b1conttp1u•I. Th< f•a th•• •mSI~ •« able 10 go back •nd

lonh bccwttn l\ltl d1ffcrtn1 lanlhqpcs of 1ymboll, valuc>, mu~mm

:and styln, .1ndlor opcratf' w1th1n a .. chird l;and.sc.apc" th~u cncom·

passes both. ...10

To-ing and fro-mg bctw«0n multiple acs1hc11c: rcpcrmircs and vcn·

ucs including mainsiream galleries, museums, and colleciors as wcll •s

ohem•nve infrastructures acatcd by El Movim1c1110, Chicano ar1is1s

Chic"'° 1'1<M:mcnt/Chlano Art

hg. 9·6. Johti

Valade~.

8fOld\v3y

~tura l (drlatl), l'JHJ-SZ

14S

Reproduced. b)' pmn1<•

SJOn of 1hc art't:lt.

question and subvert totalizi11g notions of cultural coherence, wholeness, and fi xity. Contcmpornrry revisions of idcn111y and culture affirm

that borh concepts '1rc open •nd offer the po;s1bility of making and

remaking oncsell from withm 3 living, changing 1rad111on.

In c:onrc111porary Chicano :ire, no :i rusdc current 1s dominant.

f'igurnrion ;llld nbs1raction, roliric::il .1rt 3nd ~cl f·rcfercnual an, art of

process, performance, and video nll lrnve lldherents and advocnt~.

The rhrend of unity is a sen;c of vitality :md con11n11al maruration. The

moinmean1 nrr ci rcuit continue> to uphold rigid ond stcreotypocal

noiions in its primitivistic and folkloristic cntcgoroia11Qn• of "ethnic

nrt." This is nn elite pcrspcct ivc thnt blothdy rdq;arc; highly trained

artbts in 10 n nether regiou in whi~h Chicano .irt 1:, 1n~criht.:d 1n :in

imagined world tha t os n pe rpetual fiem• of lmght colors and folk

idiom>-• world in which ;oc1.1I comcnt is onterprc1cd as .1 cultural

form unconnected IO politico I nnd •<>cinl >Cn>1btl111cs.

For the denizens of the nrts c>1abli>hmc11t, Clucono Mt" unrn>1ly

11cc:omn1odnted v. ithin t \ VO vit•wpoinis. h c:in be \Vtloon1cd and cclc-·

brated under 1hc rubric of pltirnli>m, .1 da;sificnt1on that pcrnussovdy

,1llows n sort of supcrmnrkct like .trrny of chooccs nmong ;rylcs, tech·

111qucs, nnd contents. Whole >1Cmm1ng from a dcrnocra11c impulse to

1

•3loda1c ond rccognou dl\crsoty. pluralism scnn •lso to commodofy

an, d1S3rm 2ltcm211vc r<pr~nmoons. and dclkct oni.iom•m>. Im·

pertoncn1 ond OUl·Of·bounJ, c1hn1c visions >re embraced as cncrgcuc

new Vl~l3S tO be r3podly pr(l('cs_.-J 3nd oncorpot31cd IOIO J>Ctophctal

;p.occ• wi1h111 1hc am corcu 11, 1hcn promp1ly dosordcd on 1hr )tirly

cydc of new model>.IW1ta1 mnoim In place •s <1<rnal and cam>nic3J

arc 1hc consrcra1cd 1d1on» of l'uro·ccnl<rtd •rt. ~tn from ano1hcr

pcrsJ>tCU\'t', the po'vrr strut.turc of m;unsrrcim -1n toum;1J,~ tnucs,

g•llencs, and mu~ms srlrcto•dy ~ and '31odaics "h>t 11

ptOJ«1S, dcs1rrs, and 1mpo.cs as consmucm cltmcnb of •uoous al·

tcrn:iu,·e Jrustic d1scourk\ for .. H1sp:a.n1c" 3rt. thas wltett\t 1ncor·

pomoon ofion foregrounds anwork dttm<d "colorful," "folkloroc,"

"drcorJuvc," and un1aon1rJ with OHM polmc:il comcn1. '&'!ult tit·

mcms of ohcsc mod•hues m1gh1 be pr.sen1on1hc JM1>tot prc>ductoon of

" I h>panoc" ort1s1s, 1hey do 1101 nccrssanly cohere in10 consi.1cn1 •nd

defining srylosric fearurcs.

Inscribed wi1hin muluplc clau·b•std and rq:ional 1r•d111ons, Cho·

canos in 1hc United Su1es have •ct1Y2tcd complex mechanisms ol

culru<JI ncgorianon, a dynamic procrss of analysis and 1ht exchange

of opuons bcN·ccn cultur~. In •n omcrconnccrcd "'orld S)-Sltm, tra·

douons •re los1 and found, and •nslcs ol nsion accommodate fonru

Fe.,.• t . - J - Honky TO<lk

d<wfl, 19'1, Rqwo.IU<<d by pcrn11•""" o( 1h<

"""'·

and styles from Forst and Tiurd World modernist tradirions ns well as

from evolving signifying pracriccs in the barrio. What is vigorously

defend«! is a cho1cr of ahrmarives.

In the vuual am, this pr<>ttSS of cultural negotiation occurs m

d1ffcrn11 ways. At th< lcv<I of iconography and symbolism, for exampit, the Chicano artist ofttn creates a pcrsonal visual vocabubry freely

bknd1ng and 1uxraposing symbols and images cull«! from African

Amcncan, Nam·c Amencan, European, and mcsnzo cultur•I source>.

Resonating W1th the power ascribed to rhe symbols within each culture, rhc ~w combinauon emerges dense with multifarious meaning.

Bqond symbols, arrisric styles and art·hmorial movements are con·

nnually appropna1cd and recombined on a ronstani and richly nuanced 1nrerchange. Current Chicano arr can be seen as ,1 visual n3r·

rauon of cultural negouauon.

Presently 1n 1hc Un11«1 Siates. en1rcncb«I sysicms of conirol and

domonauon affirm and uphold dis11nn1ons bctwcrn "us" and "them."

Dichotomies such as wh11t/nonwh11e, Enghsh·spcakong/Spamsh·

spcaktng. the haves/rhe ha,.c-nots, etc., pcrsm and are based on social

reahry. We should nor dissemble on tho> fact, bu1 neither ;hould we

maontmn vicious and pcrm•nent dw111ons or permit dogma uc closure.

My own sense of the d1alccuc lS 1ha1 in 1he currcn1 muggle for

I •I'·

~·'I,

;htt.111.1 AfC'f.I

H.Juu, Ah.ir lur ~.Jrll.1 Tc·

It"\••· I 'I\ ( 1101,11/Jlll''' iJI

tl•t {),. Sa1S$el A111,4"t1,,1.

l'hvto b' ~ol1pn1 °"'7<.

Reprodu ~"td

by pcrnu~"i i()n

o( 1h c :utut

cultural maintenance :and panty \\ uh1n tht C hica.no con1n1uni1y1 there

art two don1in.ant SlJ'3tcgies vying for ascendancy. On tht one hand,

the-re is an autmpt to fractu~ m;unsrrcan1 consensus wuh a defiant

"orherness." lmpettincnr reprcscnt.uion> counter 1he homogenizing

desires, 1nvcstmtntsJ and pro1tction> of the dom1n3nt culture :ind ex·

press whar is mainfcsrly different. On rhc 01hcr hand, rhere is the

rtcogmuon of nrw nucrconn<cnons and 6lia11ons, espedally wuh

orher Lanno groups 1n rhe Unired Stares. Confronting 1he dominanr

cuhurr luds 10 a rrcogn111on !hat Anglos' visions of Chicanos and

Ch1anos· visions of rhcmsrlvl's support and ro .1n extent reflect each

or her.

ltuher rhan llo"mg from a monoluh1c aes1he11c, Chicano arr

forms nrisc fro rn rac11ral. ~crntegh:, :and positional neccssitic;. \X'hat

Carlos \.lons1v.is h•s call<J /J culturil d• /11 t1ut11daJ (the cuhur< of

nccessny) lead~ to Au1d 1nult1voc.tl cxchnU8CS a111ong shifting culturJI

••g.. •-10

M1.1W \Cn.r·

the Var·

8.J1lf1. (~mtnt ot

£'-""" I 91' .. tHJ.L1lLt11rw "'

tlN ltttTA.R Llt• Amn1·

<.41f. (o.tftny, /'l:l':M! \'oti.

Rcp<odl><"<d by.,.,.........,

of rhr anu1.

traditions. A consistr.nt objccti\'C of Chicano an is to undem1ine: im·

posed models of rt'.prcsc-ntarion and to interrogate systems of aesthetic

discourse, disclosing them as neither natural nor sccu"' but conven·

tional and historically determined.

Chicano art and artists are inscribed within multiple aes1he1ic

rradiuons, both populu and elito. Their task is 10 recode themselves

and move beyond dichotomies in a nuid process of culrural negotta·

tion. This negotiation 'IJSUalJy renects culruraJ change, variation by

gender and region, and tensions within and among classes and groups

of people, such as Mexican nationals or other ethnic minorities in the

United States.

In the dynamism of such • conmnporary social reality, interests

are culrurally mediated, replaced, and created through what is collectively valued and worth struggling for. The task continues, and remains open.

NOTES

I. This text IJ • r<workmg of my unpublished manuscript Ctl1f•1: Ctl1forn1•

Ch1et1no Arr and Its Sotlt1l 8t1ellgro11nd. Scceions hov• b<<n ••«rpecd in

CMU1J10 Uf"tulons: A Ntw Vi<w in Amtriun Art (Ncw York: IN"TAR Lann

Amcncon Gallery, 1986) •nd Tli• M11ral l'rim11 (Venice, C•lil.: Soc:lol and

Pllbl1c !\<source unctr, 1987). My analyses parolkl1 ideas en James Oeflord,

Tnt p,.d1<4mtnt of Cu/tum T1u1,.tl<1l1·C•nt11')' Btlmogr~phy, 1..lttrQllffl and

Ari (C.mbn<lgt: Harvard Univcrdty Prm, 1988).

2. Tomu Rivero, Into tht l.obyrlnth: 1'ht Chicano 111 Utlf•t•fl (Edinburg,

T<xas: P•n American Un1Versiey, 197 1),

J. Esteban Villa, iapod 1ntervi<w, 1979, 1n pOHffi•on ol eh< author.

4. Kay Tum<r and l'or J"P<'• "La C•uso, La Calle y La Esquina: A Look ac

An Among Us," en Art Among U>: M•xiCRn Amtrica11 Pol• Art of San An·

tonio (Son Antonio: Son Antonio Museum Association, 1986).

S. See the caralog j.sus H1/g,,11n: El Ctlendario Como Arte (Mexico City:

Subsocrtt• n• de CuhurolProVOm• Cultural de Las Ft0nt<ru, 1987).

6. Tomas Ybarra·frausro, "Rasquachis1no: A Chic•no Sensibility," in

l!JuqJUJdtumo: Ch1u110 Aesthe11e (Phoonix: Movimicnto Artisuco Del Rio

Salado, 1988).

7. Sec Sh1fro M. Goldm•n, " A Public Voice: Fiftmc Years ol Chicano Post·

ttl," Art Journt1/ "4, no. I (Spring. 1984).

8. Victor Sor<ll, "The Photoyaph as a Sourcc for Vi1ual ArtiSts: Images From

the Ardnvo Casaoola m the Works ol Mexican and Chicano Art.ists," in The

World of AguJtin Vi<tor Ca.asola: M.xieo 1900-1938 (Waahington, D.C.:

Fonda dd Sol Visual Arts and Media une<r, 1984).

9. JU<bth Baca, "'Muralt/Pllblic An,• in Chi<411o fxprenions: A Ntw View in

American Art (New York: INTAR Laein American Gallery, 1987), 37.

10. Guillamo Coma~Peiia, .. A New Arrisric Continent," High Ptrformanu

9, no. 3 ( 1986), 27.