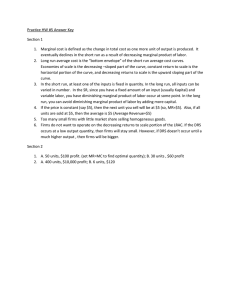

Managerial Economics & Organizational Architecture Textbook

advertisement