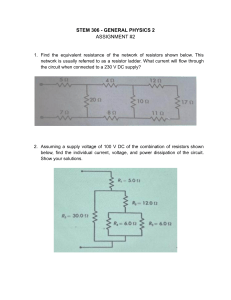

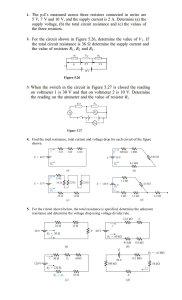

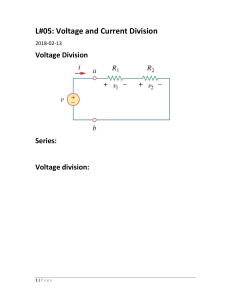

Testing Electronic Components with a Multimeter

advertisement