Economics for Engineers 7ca909f368f742869536f3c26089de65yashsnotiondefault

advertisement

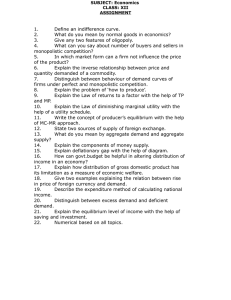

Economics for Engineers Unit 1 Introduction to Economics - Definition Basic Economic Problems Resource Constraints and Welfare Maximization Microeconomics and Macroeconomics Production Possibility Curve Circular Flow of Economic Activities Basics of Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium: Demand Side and Supply Side of the Market Factors Affecting Demand and Supply Elasticity of Demand and Supply: Price, Income, and Cross-Price Elasticity Market Equilibrium Price Unit 2 Theory of Consumer Choice - Theory of Utility and Consumer's Equilibrium Indifference Curve Analysis Budget Constraints Consumer Equilibrium Demand Forecasting: Regression Technique Time-Series Forecasting Smoothing Techniques: Exponential Moving Averages (EMA) and Moving Averages (MA) Method Unit 1 Introduction to Economics - Definition Definition of Economics: Economics is the social science that studies how individuals, businesses, and governments allocate limited resources to satisfy unlimited wants and needs. It is the study of how societies manage their resources, produce and distribute goods and services, and make choices in a world with scarce resources. Key Concepts and Components: 1. Scarcity: At the heart of economics is the concept of scarcity. Scarcity refers to the limited availability of resources, including land, labor, capital, and Economics for Engineers 1 entrepreneurship. Because resources are finite, individuals and societies must make choices about how to allocate these resources effectively. 2. Choice: Economics is fundamentally about choice. Individuals and organizations must decide how to allocate their resources to achieve their goals. These choices involve trade-offs, as allocating resources to one option often means forgoing another. 3. Opportunity Cost: When making choices, individuals and businesses need to consider the opportunity cost. Opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative that is given up when a choice is made. It highlights the real cost of decisions. Branches of Economics: 1. Microeconomics: Microeconomics focuses on individual economic units, such as households, firms, and markets. It examines how these units make decisions, interact, and allocate resources efficiently. 2. Macroeconomics: Macroeconomics, on the other hand, looks at the economy as a whole. It studies national and international economic issues, including economic growth, inflation, unemployment, and government policies that affect the entire economy. Scope of Economics: Economics has a broad scope and covers a wide range of topics, including but not limited to: Demand and Supply: Analyzing how markets determine prices and quantities of goods and services based on consumer demand and producer supply. Production and Costs: Examining how businesses produce goods and services, including the factors of production, production functions, and cost structures. Market Structures: Evaluating different market structures like perfect competition, monopoly, oligopoly, and monopolistic competition and how they impact the behavior of firms. National Income and Business Cycles: Studying how a country's income is measured and how fluctuations in economic activity, known as business cycles, affect an economy. Formulas and Equations: Economics for Engineers 2 While the introductory definition of economics doesn't involve specific formulas, you will encounter various mathematical and graphical tools in microeconomics and macroeconomics to analyze economic concepts and relationships. These may include equations for supply and demand, production functions, and economic indicators. Examples: An individual decides to spend their income on either buying a smartphone or a laptop. The opportunity cost is the value of the item they didn't choose. A business must decide how many workers to hire. They will consider the marginal cost of hiring an additional worker and the additional output or revenue that worker will generate. A government implements a policy to reduce inflation. Macroeconomists will study the effects of this policy on the overall economy, including unemployment rates and GDP growth. In summary, economics is the study of how individuals and societies make choices in the face of limited resources to meet their needs and wants. It is a diverse field with both microeconomic and macroeconomic components, and it provides valuable insights into decision-making, resource allocation, and the functioning of economies. Basic Economic Problems Introduction: Basic economic problems, also known as fundamental economic problems, are the central issues that all economic systems must address. These problems stem from the scarcity of resources relative to unlimited human wants and needs. Understanding and solving these problems is fundamental to the study of economics. The three primary basic economic problems are: 1. What to Produce: This problem concerns the allocation of resources to the production of various goods and services. Every society must decide which goods and services to produce based on the preferences and needs of its population. The choice of what to produce is influenced by factors such as consumer demand, resource availability, technology, and government policies. Economics for Engineers 3 For example, a society must decide whether to allocate resources to produce more food, healthcare, or entertainment goods. 2. How to Produce: This problem deals with the methods and techniques of production. It involves decisions about the combination of resources (land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship) used in the production process. The "how to produce" decision includes considerations of efficiency, costeffectiveness, and the impact on the environment. For instance, a society must determine whether to use labor-intensive or capital-intensive methods to manufacture a particular product. 3. For Whom to Produce: This problem addresses the distribution of goods and services among the population. It involves determining who gets to consume the produced goods and services and in what quantities. Different economic systems have various mechanisms for distribution, such as market prices, government subsidies, or rationing. This decision reflects questions about equity and social justice in resource allocation. For example, should the distribution of healthcare services be based on need, income, or some other criteria? Additional Economic Problems: In addition to the basic economic problems, other issues arise in complex modern economies. These include: 1. How to Promote Economic Growth: While addressing the basic problems is essential for maintaining a stable economy, promoting economic growth is a concern in most economies. Strategies for stimulating growth include investments in infrastructure, education, and research and development. 2. How to Control Inflation and Unemployment: Managing inflation (the rise in the general price level) and unemployment rates are critical objectives for macroeconomic policy. Governments and central banks use monetary and fiscal policies to address these issues. 3. How to Address Environmental Sustainability: Economics for Engineers 4 In the face of environmental challenges, economies must also consider how to produce and consume in a manner that is sustainable and environmentally responsible. Impact of Basic Economic Problems: The way a society addresses these economic problems has significant implications for its economic structure, distribution of wealth, and overall well-being. Different economic systems, such as capitalism, socialism, and mixed economies, approach these problems in distinct ways. Capitalist economies rely on market forces to determine what to produce, how to produce, and for whom to produce. Prices play a crucial role in these decisions. Socialist economies may involve central planning to make decisions on what, how, and for whom to produce, with a focus on social equity. Mixed economies combine elements of both capitalism and socialism, attempting to strike a balance between efficiency and equity. In summary, basic economic problems arise from the scarcity of resources relative to human wants and needs. Addressing these problems is central to the functioning of economic systems, and how they are addressed varies depending on the economic system in place. These decisions have far-reaching effects on the distribution of resources and the overall well-being of a society. Resource Constraints and Welfare Maximization Resource Constraints in Economics: Resource constraints refer to the limitations and scarcity of resources that an economy faces when making choices about what to produce, how to produce, and for whom to produce. These constraints are a fundamental aspect of economic decision-making and impact the welfare and well-being of individuals and society as a whole. Several key points related to resource constraints include: 1. Limited Resources: Resources such as land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship are limited and finite. In economic terms, this is often referred to as scarcity. Since resources are scarce, choices must be made regarding their allocation. 2. Opportunity Cost: When resources are allocated to produce one good or service, there is an opportunity cost associated with forgoing the production of Economics for Engineers 5 other goods and services. Opportunity cost represents the value of the next best alternative that had to be sacrificed. 3. Trade-offs: Because of resource constraints, individuals, businesses, and governments must make trade-offs. They must balance competing interests and allocate resources in a way that maximizes their utility or benefit. Welfare Maximization in Economics: Welfare maximization is the goal of economic decision-making, where the objective is to maximize the overall well-being and satisfaction of individuals and society. In the context of resource constraints, welfare maximization involves making choices that lead to the highest possible level of overall satisfaction. Key concepts related to welfare maximization include: 1. Utility: In economics, utility is a measure of an individual's satisfaction or wellbeing. Welfare maximization seeks to increase the utility of individuals and society as a whole. 2. Pareto Efficiency: A situation is said to be Pareto efficient when it is impossible to make any individual better off without making someone else worse off. Achieving Pareto efficiency is a way to maximize overall welfare without harming anyone. 3. Equity and Fairness: While maximizing welfare is essential, equity and fairness considerations are also important. Welfare maximization should be achieved in a way that doesn't lead to extreme inequalities and considers the distribution of resources and benefits. Optimal Resource Allocation for Welfare Maximization: To address resource constraints and maximize welfare, economic systems and policymakers use various approaches and tools: 1. Market Mechanisms: In a market-based economy, prices and market forces play a significant role in allocating resources efficiently. Resources flow to areas where they are in high demand, and prices reflect the relative scarcity of goods and services. 2. Government Intervention: Governments often intervene to correct market failures and ensure the equitable distribution of resources. They implement policies such as taxation, subsidies, and regulations to influence resource allocation. Economics for Engineers 6 3. Social Safety Nets: Social safety nets, such as welfare programs, unemployment benefits, and healthcare systems, are designed to provide a minimum level of well-being to those who may not fully benefit from market mechanisms. 4. Cost-Benefit Analysis: In decision-making, especially in the public sector, costbenefit analysis is used to assess the trade-offs of various policy choices. It helps determine which policies will maximize welfare by comparing the costs and benefits. 5. Innovations and Technological Advancements: Technological progress can expand the availability of resources, improve resource utilization, and enhance overall welfare. Examples: In a market economy, if the demand for renewable energy sources (e.g., solar panels) increases, resources may be redirected toward their production, benefiting both consumers and the environment. A government may allocate resources to provide universal healthcare, aiming to improve the overall welfare and health of the population. During a natural disaster, resource allocation may be prioritized to provide relief and support to affected areas, demonstrating a shift in allocation based on immediate needs. In summary, resource constraints are a fundamental aspect of economic decisionmaking, and welfare maximization is the goal of allocating resources to achieve the highest level of well-being for individuals and society. Achieving this goal requires balancing efficiency, equity, and fairness, and it often involves a combination of market mechanisms, government intervention, and social safety nets. Cost-benefit analysis and technological advancements also play a role in optimizing resource allocation for maximum welfare. Microeconomics and Macroeconomics Microeconomics: Microeconomics is the branch of economics that focuses on the behavior of individual economic agents and small economic units, such as households, firms, and markets. It examines how these units make decisions, interact with each other, Economics for Engineers 7 and allocate resources efficiently. Key concepts and topics in microeconomics include: 1. Demand and Supply: Microeconomics analyzes how consumers and producers interact in markets. Demand refers to the quantity of a good or service that consumers are willing and able to buy, while supply represents the quantity that producers are willing and able to sell. Equilibrium in the market occurs when demand equals supply, determining prices and quantities. 2. Consumer Behavior: Microeconomics delves into how consumers make choices, considering factors like preferences, budget constraints, and utility maximization. It explores concepts such as indifference curves and consumer surplus. 3. Production and Costs: Microeconomics examines the production processes of firms and the costs associated with producing goods and services. Topics include production functions, cost curves, and profit maximization. 4. Market Structures: Microeconomics categorizes markets into various structures, including perfect competition, monopoly, oligopoly, and monopolistic competition. Each structure has unique characteristics that influence the behavior of firms and the allocation of resources. 5. Factor Markets: The analysis of factor markets focuses on the supply and demand for factors of production, such as labor and capital. Wage determination, rent, and interest rates are explored in this context. 6. Price Elasticity of Demand and Supply: Understanding how sensitive the quantity demanded or supplied is to changes in price is critical in microeconomics. Price elasticity measures the responsiveness of buyers and sellers to price changes. Macroeconomics: Macroeconomics, in contrast, studies the economy as a whole. It deals with aggregate economic phenomena and aims to understand the broader issues affecting an entire nation or the global economy. Key concepts and topics in macroeconomics include: 1. Gross Domestic Product (GDP): GDP is a fundamental macroeconomic indicator that measures the total value of goods and services produced within a country's borders over a specific period. It provides insight into an economy's size and growth. Economics for Engineers 8 2. Inflation and Deflation: Macroeconomics examines changes in the general price level. Inflation refers to the increase in prices over time, while deflation is the opposite. Central banks monitor and control inflation to maintain price stability. 3. Unemployment: Macroeconomics analyzes the labor market and measures the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed. It investigates the causes and consequences of unemployment. 4. Monetary Policy: Central banks, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States, implement monetary policy to control the money supply, interest rates, and credit conditions. These policies impact inflation, employment, and economic stability. 5. Fiscal Policy: Governments use fiscal policy, involving taxation and government spending, to manage economic activity. Changes in taxation and government spending can influence aggregate demand and economic growth. 6. Business Cycles: Macroeconomics studies economic fluctuations, known as business cycles, which include periods of economic expansion, recession, and recovery. Understanding these cycles helps policymakers make informed decisions. 7. International Trade and Exchange Rates: The global aspect of macroeconomics focuses on international trade, exchange rates, and the balance of payments. These factors have implications for a country's economic stability and growth. Interactions between Microeconomics and Macroeconomics: While microeconomics and macroeconomics are distinct subfields, they are interrelated. Microeconomic decisions by households and firms collectively influence macroeconomic outcomes. For example, household spending and business investment contribute to GDP, while individual labor market decisions impact overall unemployment rates. Conversely, macroeconomic factors can also affect microeconomic conditions. Inflation and interest rates, controlled by macroeconomic policies, impact consumer and business behavior, influencing their decisions on spending, investment, and pricing. In summary, microeconomics and macroeconomics are two fundamental branches of economics, each addressing different aspects of economic behavior and performance. Microeconomics focuses on individual economic agents and market Economics for Engineers 9 interactions, while macroeconomics examines aggregate economic phenomena and policy implications at the national or global level. These two branches complement each other, providing a comprehensive understanding of the functioning of economies. Production Possibility Curve Definition: A Production Possibility Curve (PPC), also known as a Production Possibility Frontier (PPF), is a graphical representation used in economics to demonstrate the maximum combination of two or more goods and services that an economy can produce given its available resources and technology, assuming full utilization of resources and efficiency in production. Key Concepts: 1. Scarce Resources: The PPC is based on the fundamental economic concept of scarcity, which means that resources (such as labor, capital, land, and technology) are limited, and choices must be made about how to allocate them efficiently. Economics for Engineers 10 2. Opportunity Cost: The PPC illustrates the concept of opportunity cost, which is the cost of forgoing the production of one good or service to produce more of another. As an economy moves along the PPC, it must give up some of one good to produce more of another. 3. Efficiency: The PPC assumes that the economy is operating at full efficiency, meaning that it is using all available resources to their maximum potential. Characteristics of the PPC: 1. Bowed-Outward Shape: The typical PPC has a bowed-outward or concave shape. This shape represents the idea that resources are not equally productive in all activities. As an economy specializes in producing more of one good, the opportunity cost of producing that good increases, causing the PPC to curve outward. 2. Boundary: The PPC is a boundary or frontier that shows the maximum possible combinations of goods that an economy can produce. Points on the curve represent efficient allocation of resources, while points inside the curve represent underutilization of resources, and points outside the curve are unattainable given the current resources and technology. 3. Shifting the PPC: The PPC can shift over time due to changes in resource availability, technological advancements, and changes in the labor force. An outward shift of the PPC represents economic growth, while an inward shift may indicate resource depletion or economic decline. Illustration and Interpretation: Let's consider a simplified example of a PPC with two goods: "Cars" and "Computers." The PPC demonstrates the trade-off between these two goods. Here are some points of interpretation: Point A: This point represents a situation where the economy is producing a balanced mix of cars and computers. It's an efficient use of resources, and it's on the PPC. Point B: At this point, the economy is producing more computers but fewer cars. The opportunity cost of producing more computers is fewer cars. It's still on the PPC but is an allocation choice. Point C: This point is unattainable with the current resources and technology. It's outside the PPC, indicating that the economy cannot produce this combination of cars and computers given its limitations. Economics for Engineers 11 Point D: This point is inside the PPC, representing an inefficient allocation of resources. The economy could produce more of both goods without sacrificing one for the other. Factors Shifting the PPC: 1. Technological Advancements: Technological progress can lead to an outward shift of the PPC, allowing an economy to produce more of both goods with the same resources. 2. Resource Discovery: The discovery of new resources or improved resource utilization can also shift the PPC outward. 3. Changes in the Labor Force: An increase in the labor force or improvements in workforce skills can result in a more efficient use of resources and an outward shift. 4. Economic Growth: Economic growth, often driven by increased investments, can lead to an expansion of the PPC. In summary, the Production Possibility Curve (PPC) is a graphical representation that shows the maximum combinations of goods and services an economy can produce with its available resources and technology, assuming full resource utilization and efficiency. It illustrates the trade-offs between different goods and the concept of opportunity cost. Shifts in the PPC can occur due to technological advancements, resource changes, labor force changes, and economic growth. Economics for Engineers 12 Circular Flow of Economic Activities Definition: The circular flow of economic activities is a simplified model used in economics to illustrate how the different sectors of an economy interact and exchange goods, services, and money. This model is designed to show the flow of resources, income, and expenditures between households, businesses, and the government. It provides a basic framework for understanding the functioning of an economy. Key Components: The circular flow model consists of the following key components: 1. Households: This represents the individuals or consumers in the economy. Households supply factors of production (labor, capital, land, and entrepreneurship) to businesses and receive income in the form of wages, rent, interest, and profit. 2. Businesses (Firms): Businesses are the producers in the economy. They hire factors of production from households and produce goods and services. In return, businesses pay income to households, which includes salaries, rents, and dividends. Economics for Engineers 13 3. Product Market: This is where businesses sell goods and services to households. Households purchase goods and services from businesses, and in return, businesses receive revenue. 4. Factor Market: This is where households supply factors of production (e.g., labor, land, capital) to businesses. In exchange, households receive income in the form of wages, rent, interest, and profit. 5. Government: The government plays a role in the circular flow model by collecting taxes from households and businesses. It then uses these funds to provide public goods and services (e.g., education, healthcare, infrastructure) and transfer payments (e.g., social security, welfare). 6. Government Purchases: The government also purchases goods and services from businesses, creating an injection of funds into the economy. This includes government spending on defense, healthcare, education, and other services. 7. Taxes: Taxes represent the funds collected by the government from households and businesses. Taxes are used to finance government activities and programs. Flow of Economic Activities: In the circular flow model, economic activities flow in a circular manner through the following processes: 1. Households supply factors of production: Households provide labor, land, capital, and entrepreneurship to businesses through the factor market. 2. Businesses pay income to households: In return for the factors of production, businesses pay income to households. This income includes wages, rent, interest, and profit. 3. Households spend on goods and services: Households use the income received from businesses to purchase goods and services in the product market. 4. Businesses receive revenue: Businesses earn revenue by selling goods and services to households in the product market. 5. Businesses pay taxes: Businesses pay taxes to the government on their earnings. 6. Government provides public goods and services: The government uses tax revenue to provide public goods and services and make transfer payments to households. Economics for Engineers 14 7. Government purchases from businesses: The government also purchases goods and services from businesses, injecting funds into the economy. This circular flow continues, demonstrating the continuous exchange of resources, income, and expenditures in the economy. It reflects how households, businesses, and the government are interconnected and interdependent in the functioning of an economy. Leakages and Injections: The circular flow model also highlights the concept of leakages and injections. Leakages occur when funds are withdrawn from the circular flow, such as savings or taxes. Injections, on the other hand, represent additions to the circular flow, such as government spending or investment. The balance between leakages and injections determines the overall health and stability of the economy. In summary, the circular flow of economic activities is a fundamental model used in economics to illustrate how resources, income, and expenditures flow between households, businesses, and the government. It provides a simplified representation of the complex interactions within an economy, emphasizing the roles of various economic agents and the continuous exchange of goods, services, and money. Basics of Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium: Demand Side and Supply Side of the Market Introduction: Demand and supply are two fundamental concepts in economics that play a central role in determining prices and quantities of goods and services in the market. They represent the forces that interact to establish market equilibrium. Let's explore the demand side and supply side of the market: Demand: Definition: Demand represents the quantity of a good or service that consumers are willing and able to buy at various price levels during a specific period. Key Concepts: 1. Law of Demand: The law of demand states that, all else being equal, there is an inverse relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demanded. In Economics for Engineers 15 other words, as the price of a good decreases, the quantity demanded increases, and vice versa. 2. Demand Curve: The demand curve is a graphical representation of the relationship between price and quantity demanded. It slopes downward from left to right to illustrate the law of demand. 3. Determinants of Demand: Several factors affect demand, including consumers' income, preferences and tastes, the prices of related goods (substitutes and complements), and population demographics. Supply: Definition: Supply represents the quantity of a good or service that producers are willing and able to sell at various price levels during a specific period. Key Concepts: 1. Law of Supply: The law of supply states that, all else being equal, there is a direct relationship between the price of a good and the quantity supplied. In other words, as the price of a good increases, the quantity supplied increases, and vice versa. 2. Supply Curve: The supply curve is a graphical representation of the relationship between price and quantity supplied. It slopes upward from left to right to illustrate the law of supply. 3. Determinants of Supply: Various factors influence supply, including production costs, technology, government policies, and the number of suppliers in the market. Market Equilibrium: Market equilibrium is the point at which the quantity demanded by consumers equals the quantity supplied by producers. In equilibrium, there is no excess supply (surplus) or excess demand (shortage). Key points about market equilibrium include: At the equilibrium price, the quantity that consumers are willing to buy (demand) is exactly equal to the quantity that producers are willing to sell (supply). Equilibrium is determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves on a graph, where the two curves meet. If the price is above the equilibrium level, there will be a surplus of the product, leading to downward pressure on prices. Producers may need to reduce prices Economics for Engineers 16 to clear the surplus. If the price is below the equilibrium level, there will be a shortage of the product, leading to upward pressure on prices. Producers may raise prices to take advantage of the shortage. Illustration: Consider a simple example with the market for smartphones: Demand for smartphones may increase if consumer incomes rise, if consumers prefer smartphones to other devices, or if the population grows. Supply of smartphones may increase if production costs decrease, if new technology allows for more efficient production, or if more smartphone manufacturers enter the market. In equilibrium, the price and quantity of smartphones will be such that the quantity demanded matches the quantity supplied. If the price is too high, there may be a surplus of unsold smartphones. If the price is too low, there may be a shortage, and consumers may have difficulty finding smartphones to purchase. In summary, the demand side and supply side of the market are essential concepts in economics. Demand represents consumer preferences and their willingness and ability to buy, while supply represents the willingness and ability of producers to sell. Market equilibrium is the point at which the two forces balance, leading to a specific price and quantity of goods or services exchanged in the market. Understanding these concepts is fundamental for analyzing and predicting market behavior. Factors Affecting Demand and Supply Demand: Demand refers to the quantity of a good or service that consumers are willing and able to buy at various prices during a specific period. Several factors influence the demand for a product or service: 1. Price: The most fundamental factor affecting demand is the price of the product. According to the law of demand, there is an inverse relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demanded. When the price decreases, demand generally increases, and vice versa. 2. Income: Consumer income plays a significant role in determining demand. For normal goods, as income increases, demand for these goods also increases. For Economics for Engineers 17 inferior goods, as income rises, demand may decrease. 3. Consumer Preferences and Tastes: Changes in consumer preferences can significantly impact demand. If a product becomes more fashionable, trendy, or desirable, demand may rise. Conversely, if preferences shift away from a product, demand can decline. 4. Price of Related Goods: Substitutes: The price of substitute goods can affect demand. For example, if the price of coffee rises, the demand for tea may increase as consumers switch to the cheaper alternative. Complements: The price of complementary goods can also influence demand. For instance, if the price of smartphones falls, there may be an increase in the demand for smartphone accessories like cases and screen protectors. 5. Population and Demographics: The size and composition of the population in a market can impact demand. For example, an aging population might increase demand for healthcare services and products. 6. Consumer Expectations: Anticipated future changes in prices or income can influence current demand. If consumers expect the price of a product to rise in the future, they may buy more of it now, increasing present demand. 7. Advertising and Marketing: Effective advertising and marketing campaigns can shape consumer preferences and increase demand for a product. Supply: Supply refers to the quantity of a good or service that producers are willing and able to sell at various prices during a specific period. Several factors affect the supply of a product or service: 1. Price: The price of a product is a significant factor affecting supply. According to the law of supply, there is a direct relationship between the price of a good and the quantity supplied. When the price increases, the quantity supplied generally increases, and vice versa. 2. Production Costs: The costs of producing goods and services are crucial. When production costs, including labor, materials, and energy, rise, producers may reduce supply. Conversely, lower production costs can increase supply. 3. Technological Advancements: Improvements in technology can lead to increased production efficiency, allowing producers to supply more goods at Economics for Engineers 18 lower costs. 4. Government Regulations and Policies: Government regulations and policies can affect the supply of goods. For example, subsidies or tax incentives can encourage increased production, while regulations can restrict it. 5. Input Prices: Changes in the prices of inputs, such as raw materials and labor, directly impact production costs. If the cost of inputs rises, producers may reduce supply. 6. Number of Suppliers: An increase in the number of firms or suppliers entering a market can boost supply. Similarly, if firms exit the market, supply may decrease. 7. Natural Events and Disasters: Natural events, such as weather conditions, can impact the supply of agricultural products. A drought, for instance, can reduce the supply of crops. 8. Expectations of Future Prices: Producers' expectations of future prices can influence their current supply decisions. If they expect higher future prices, they may reduce supply now to sell at a higher price later. 9. Technological Advancements: Improvements in technology can lead to increased production efficiency, allowing producers to supply more goods at lower costs. 10. Government Regulations and Policies: Government regulations and policies can affect the supply of goods. For example, subsidies or tax incentives can encourage increased production, while regulations can restrict it. Understanding how these factors influence demand and supply is essential for analyzing market behavior and predicting how changes in these factors can impact prices and quantities in an economy. Elasticity of Demand and Supply: Price, Income, and Cross-Price Elasticity Elasticity of Demand: Elasticity of demand measures how sensitive the quantity demanded of a good is to changes in price, income, or the price of related goods. It is a critical concept in understanding consumer behavior and market dynamics. There are three main types of elasticity of demand: 1. Price Elasticity of Demand (PED): Economics for Engineers 19 Price elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded to changes in the price of a good. The formula for calculating PED is: PED = (% Change in Quantity Demanded) / (% Change in Price) PED can be classified into three categories: Elastic Demand (PED > 1): When the percentage change in quantity demanded is greater than the percentage change in price, demand is considered elastic. Consumers are highly responsive to price changes in elastic demand. Inelastic Demand (PED < 1): When the percentage change in quantity demanded is less than the percentage change in price, demand is inelastic. Consumers are not very responsive to price changes in inelastic demand. Unitary Elastic Demand (PED = 1): When the percentage change in quantity demanded is equal to the percentage change in price, demand is unitary elastic. 2. Income Elasticity of Demand (YED): Income elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded to changes in consumer income. The formula for calculating YED is: YED = (% Change in Quantity Demanded) / (% Change in Income) YED can be classified into three categories: Normal Goods (YED > 0): When an increase in consumer income leads to an increase in the quantity demanded, the good is a normal good. Inferior Goods (YED < 0): When an increase in consumer income leads to a decrease in the quantity demanded, the good is an inferior good. Luxury Goods (YED > 1): Luxury goods have a high income elasticity, indicating that consumers buy more of them as their income rises. 3. Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand (XED): Cross-price elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of one good to changes in the price of another related good. Economics for Engineers 20 The formula for calculating XED is: XED = (% Change in Quantity Demanded of Good A) / (% Change in Price of Good B) XED can be classified into two categories: Complementary Goods (XED < 0): When an increase in the price of one good leads to an increase in the quantity demanded of another related good, the goods are complementary. Substitute Goods (XED > 0): When an increase in the price of one good leads to a decrease in the quantity demanded of another related good, the goods are substitutes. Elasticity of Supply: Elasticity of supply measures how sensitive the quantity supplied of a good is to changes in price. It is essential for understanding how producers respond to market conditions. There is one primary type of elasticity of supply: 1. Price Elasticity of Supply (PES): Price elasticity of supply measures the responsiveness of the quantity supplied to changes in the price of a good. The formula for calculating PES is: PES = (% Change in Quantity Supplied) / (% Change in Price) PES can be classified into two categories: Elastic Supply (PES > 1): When the percentage change in quantity supplied is greater than the percentage change in price, supply is considered elastic. Producers are highly responsive to price changes in elastic supply. Inelastic Supply (PES < 1): When the percentage change in quantity supplied is less than the percentage change in price, supply is inelastic. Producers are not very responsive to price changes in inelastic supply. Understanding these different types of elasticity is crucial for businesses, policymakers, and economists. Elasticity provides insights into how changes in price, income, or related goods impact consumer and producer behavior, helping to make informed decisions about pricing, taxation, and market strategies. Market Equilibrium Price Economics for Engineers 21 Definition: Market equilibrium price, often simply referred to as equilibrium price, is the price at which the quantity demanded for a particular good or service in a market is equal to the quantity supplied, resulting in a state of balance where there is neither excess supply nor excess demand. It is the point at which buyers and sellers agree on the market price, and transactions occur smoothly. Key Characteristics: 1. Balance of Supply and Demand: Equilibrium price is achieved when the quantity demanded in the market equals the quantity supplied. This means that all willing buyers can purchase the quantity they desire, and all willing sellers can sell the quantity they wish to offer. 2. Price Stability: Equilibrium price is often associated with price stability. Once the market reaches this point, there is no immediate pressure for prices to rise or fall, as the market is in balance. 3. Price Determination: The equilibrium price is determined by the interaction of supply and demand forces in the market. It is where the demand curve and supply curve intersect on a supply and demand graph. 4. Market Efficiency: At equilibrium price, resources are allocated efficiently in the market. There is no waste or shortage of goods, and the market is operating optimally. Graphical Representation: In graphical terms, the equilibrium price is determined at the point where the demand curve and supply curve intersect on a supply and demand graph. The point of intersection is also known as the equilibrium point. At this point, the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied. If the price is above the equilibrium price (P > Pe), it indicates a surplus in the market, as the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. This typically leads to downward pressure on prices as sellers may need to lower prices to clear the surplus. If the price is below the equilibrium price (P < Pe), it indicates a shortage in the market, as the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied. This typically leads to upward pressure on prices as sellers may increase prices to take advantage of the shortage. Factors Affecting Equilibrium Price: Economics for Engineers 22 Several factors can affect the equilibrium price in a market: 1. Changes in Demand: An increase in demand, caused by factors like rising consumer incomes or changing consumer preferences, can push the equilibrium price higher. A decrease in demand has the opposite effect. 2. Changes in Supply: An increase in supply, often due to technological advancements or more efficient production methods, can push the equilibrium price lower. A decrease in supply has the opposite effect. 3. Market Shifts: Changes in the market, such as government regulations, can also influence the equilibrium price. For example, taxes on a product can increase its price, while subsidies can reduce the price. 4. External Events: Unexpected events, such as natural disasters or geopolitical events, can disrupt the supply chain and influence the equilibrium price. In summary, market equilibrium price is the point at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied in a market, resulting in a state of balance and price stability. It is determined by the interaction of supply and demand forces and can be influenced by changes in market conditions and external events. Understanding equilibrium price is crucial for businesses, consumers, and policymakers to make informed decisions regarding pricing, production, and market strategies. Unit 2 Theory of Consumer Choice - Theory of Utility and Consumer's Equilibrium Theory of Utility: The theory of utility is a fundamental concept in economics that helps explain how consumers make choices among various goods and services to maximize their wellbeing or satisfaction. It is based on the idea that individuals seek to maximize their utility, which represents the pleasure, satisfaction, or happiness that they derive from consuming goods and services. Key concepts related to the theory of utility: 1. Total Utility (TU): Total utility is the total satisfaction or happiness that a consumer derives from consuming a specific quantity of a good or service. It Economics for Engineers 23 typically increases as the quantity consumed increases, but at a diminishing rate. 2. Marginal Utility (MU): Marginal utility is the additional satisfaction or happiness gained from consuming one more unit of a good or service. It represents the change in total utility when consumption increases by one unit. 3. Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility: According to this law, as a consumer consumes more of a particular good, the additional satisfaction (marginal utility) derived from each additional unit decreases. This explains why individuals seek to balance their consumption of various goods to maximize overall utility. 4. Utility Function: The utility function is a mathematical representation of a consumer's preferences. It allows economists to quantify utility and model consumer choices. The utility function typically takes the form U(X, Y), where X and Y represent the quantities of two goods, and U represents the total utility. Consumer's Equilibrium: Consumer's equilibrium is a concept that combines the theory of utility with the theory of consumer choice. It represents the point at which a consumer maximizes utility by allocating their limited budget among various goods and services. Key points related to consumer's equilibrium: 1. Budget Constraint: Consumers have limited budgets and must allocate their income to purchase goods and services. The budget constraint is represented as P_x * X + P_y * Y ≤ I, where P_x and P_y are the prices of goods X and Y, X and Y are the quantities purchased, and I is the consumer's income. 2. Consumer Choice: To maximize utility, consumers choose a combination of goods X and Y that equates the marginal utility per dollar spent on each good. In mathematical terms, this equates to MU_X / P_X = MU_Y / P_Y. 3. Consumer Equilibrium Condition: Consumer equilibrium is achieved when the consumer allocates their budget such that the marginal utility per dollar spent is the same for all goods and services. This ensures that no other allocation would increase their total utility. 4. Optimal Consumption: At the point of consumer equilibrium, the consumer allocates their income to maximize total utility while satisfying their budget constraint. This is the combination of goods and services that provides the highest level of satisfaction given their budget. Illustration: Economics for Engineers 24 Suppose a consumer has a budget of $100 (I) and faces the following prices: P_X = $10 and P_Y = $5. The consumer must allocate their budget between two goods, X and Y, to maximize their total utility. This is done by comparing the marginal utility per dollar spent on each good. If MU_X / P_X > MU_Y / P_Y, the consumer should buy more of good X. If MU_X / P_X < MU_Y / P_Y, the consumer should buy more of good Y. The consumer adjusts their consumption until MU_X / P_X equals MU_Y / P_Y, at which point their total utility is maximized. In summary, the theory of utility and consumer's equilibrium are essential concepts in understanding how consumers make choices to maximize their well-being. The combination of goods and services that maximizes utility while satisfying budget constraints is the consumer's equilibrium. This concept is fundamental for analyzing consumer behavior and preferences in economic decision-making. What is an Indifference Curve? An indifference curve is a curve that represents all the combinations of goods that give the same satisfaction to the consumer. Since all the combinations give the same amount of satisfaction, the consumer prefers them equally. Hence the name indifference curve. Here is an example to understand the indifference curve better. Peter has 1 unit of food and 12 units of clothing. Now, we ask Peter how many units of clothing is he willing to give up in exchange for an additional unit of food so that his level of satisfaction remains unchanged. Peter agrees to give up 6 units of clothing for an additional unit of food. Hence, we have two combinations of food and clothing giving equal satisfaction to Peter as follows: 1 unit of food and 12 units of clothing 2 units of food and 6 units of clothing By asking him similar questions, we get various combinations as follows: Combination Food Clothing A 1 12 B 2 6 C 3 4 D 4 3 Graphical Representation: Economics for Engineers 25 indifference curve The diagram shows an Indifference curve (IC). Any combination lying on this curve gives the same level of consumer satisfaction. Another name for it is Iso-Utility Curve. Indifference Map An Indifference Map is a set of Indifference Curves. It depicts the complete picture of a consumer’s preferences. The following diagram shows an indifference map consisting of three curves: We know that a consumer is indifferent among the combinations lying on the same indifference curve. However, it is important to note that he prefers the combinations on the higher indifference curves to those on the lower ones. Economics for Engineers 26 This is because a higher indifference curve implies a higher level of satisfaction. Therefore, all combinations on IC1 offer the same satisfaction, but all combinations on IC2 give greater satisfaction than those on IC1. Indifference Curve Analysis Indifference curve analysis is a fundamental tool in microeconomics used to understand and analyze consumer preferences and choice. It is based on the concept of indifference curves, which represent different combinations of goods or services that provide the same level of satisfaction (utility) to a rational consumer. Here are the key components and principles of indifference curve analysis: Components of Indifference Curve Analysis: 1. Indifference Curves: An indifference curve is a graphical representation showing various combinations of two goods that yield the same level of satisfaction to a consumer. Each curve represents a different level of satisfaction, with higher indifference curves indicating greater satisfaction. 2. Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS): The MRS measures the rate at which a consumer is willing to trade one good for another while staying on the same indifference curve. It is the slope of the indifference curve and represents the consumer's preference for one good relative to the other. Economics for Engineers 27 3. Transitivity: The consumer's preferences are assumed to be transitive, meaning that if the consumer prefers bundle A to bundle B and prefers bundle B to bundle C, then the consumer also prefers bundle A to bundle C. 4. Completeness: It is assumed that a consumer can compare and rank different bundles of goods. That is, for any two bundles of goods, a consumer can determine which one they prefer or if they are equally preferred. 5. Monotonicity: The consumer's preferences are assumed to be monotonic, meaning that more of any good is preferred to less. In other words, consumers prefer higher quantities of goods to lower quantities. Principles of Indifference Curve Analysis: 1. Diminishing Marginal Rate of Substitution: Indifference curves are typically convex to the origin, indicating that as a consumer moves along the curve from left to right, they must receive more of one good to compensate for receiving less of the other. This principle reflects the law of diminishing marginal utility. 2. Consumer Equilibrium: Consumer equilibrium is reached when the highest attainable indifference curve is tangent to the budget constraint. At this point, the consumer maximizes utility, subject to the budget constraint, by choosing a specific combination of goods. The MRS between the goods should equal the price ratio (the slope of the budget constraint). 3. Income and Substitution Effects: Changes in income or prices of goods lead to income and substitution effects. An increase in income may shift the budget constraint outward, causing the consumer to buy more of both goods. A change in the price of one good may lead to a substitution effect (increasing the consumption of the relatively cheaper good) and an income effect (resulting from the change in real income). Illustration: Consider a consumer who is choosing between goods X and Y. Indifference curve analysis involves drawing multiple indifference curves, each representing a different level of satisfaction. The consumer's goal is to maximize utility while staying within the budget constraint (the available income to spend on X and Y). The point where the highest attainable indifference curve is tangent to the budget constraint represents consumer equilibrium. Applications: Indifference curve analysis is widely used in economics to analyze consumer choices, price changes, income changes, and welfare economics. It helps Economics for Engineers 28 economists understand consumer behavior, evaluate the impact of policy changes, and make predictions about how consumers will respond to various market conditions. In summary, indifference curve analysis is a valuable tool for understanding consumer preferences and choices. It provides insights into how consumers make trade-offs between different goods and services to maximize their utility while adhering to budget constraints. It is a foundational concept in microeconomics that has applications in various economic analyses and decision-making processes. Budget Constraints A budget constraint is a fundamental concept in economics that represents the limit on a consumer's spending, given their income and the prices of goods and services. It illustrates the different combinations of goods and services that a consumer can afford, subject to their available income. Key components and principles related to budget constraints: Components of a Budget Constraint: 1. Income (I): The consumer's budget constraint starts with their income, which represents the total amount of money they have available to spend on goods and services. 2. Prices of Goods (P_x and P_y): Prices of goods and services (P_x and P_y) represent the cost per unit of each product. Different goods have different prices, and these prices affect how much of each good the consumer can afford. 3. Quantity of Goods (X and Y): The consumer's choice of how much of each good to purchase is represented by the quantities X and Y. Budget Constraint Equation: The budget constraint can be represented by the following equation: I = P_x * X + P_y * Y I: The consumer's income. P_x: The price of good X. P_y: The price of good Y. X: The quantity of good X purchased. Economics for Engineers 29 Y: The quantity of good Y purchased. This equation illustrates that a consumer's income (I) must be spent on goods X and Y, taking into account their respective prices. Graphical Representation: On a two-dimensional graph where the X-axis represents the quantity of good X and the Y-axis represents the quantity of good Y, the budget constraint is depicted as a straight line. The slope of the line is determined by the price ratio (P_x / P_y). The intercept on the X-axis represents the maximum quantity of good X that can be purchased, given the consumer's income and the price of good X, while the intercept on the Y-axis represents the maximum quantity of good Y. Consumer Equilibrium and the Budget Constraint: Consumer equilibrium occurs when the consumer maximizes their utility (satisfaction) subject to the budget constraint. This involves choosing a combination of goods (X and Y) that lies on the budget constraint and provides the highest level of satisfaction. The consumer's choices are made based on their preferences and the trade-off between the prices of goods. Shifts in the Budget Constraint: The budget constraint can shift due to changes in the consumer's income or the prices of goods. If the consumer's income increases, the budget constraint shifts outward, allowing them to afford more goods. Conversely, a decrease in income shifts the budget constraint inward. Changes in the prices of goods also affect the budget constraint. An increase in the price of one good shifts the budget constraint to the left, reducing the quantity of that good the consumer can afford. A decrease in the price of one good shifts the budget constraint to the right, allowing the consumer to afford more of that good. In summary, a budget constraint is a representation of the financial limitations a consumer faces when making choices about how to allocate their income to purchase goods and services. Understanding the budget constraint is crucial for analyzing consumer choices, price changes, and income changes in microeconomic decision-making. Consumer Equilibrium Economics for Engineers 30 Consumer equilibrium is a fundamental concept in microeconomics that refers to the point at which a consumer maximizes their satisfaction or utility, subject to their budget constraint. It is the outcome of rational decision-making by consumers when they allocate their limited income to purchase goods and services. Key principles and components related to consumer equilibrium: Components of Consumer Equilibrium: 1. Income (I): Consumer equilibrium begins with the consumer's income, which represents the total amount of money available to spend on goods and services. 2. Prices of Goods (P_x and P_y): The prices of goods and services (P_x and P_y) are crucial factors influencing consumer choices. Different goods have different prices, which affect the consumer's ability to afford them. 3. Utility Function: The utility function is a mathematical representation of the consumer's preferences, indicating the level of satisfaction or happiness associated with different combinations of goods and services. 4. Marginal Utility (MU_x and MU_y): Marginal utility represents the additional satisfaction or happiness derived from consuming one more unit of a good or service. It is essential for decision-making, as consumers aim to maximize their utility. Principles of Consumer Equilibrium: 1. Marginal Utility per Dollar: To achieve consumer equilibrium, the consumer allocates their income among various goods in such a way that the marginal utility per dollar spent on each good is equal. In mathematical terms, it is expressed as MU_x / P_x = MU_y / P_y. 2. Budget Constraint: The consumer's budget constraint is an essential component of achieving equilibrium. It ensures that the consumer does not spend more than their available income. The budget constraint is represented as I = P_x * X + P_y * Y, where X and Y are the quantities of goods consumed. 3. Consumer Choice: To reach equilibrium, the consumer selects the combination of goods X and Y that maximizes their total utility while staying within the budget constraint. 4. Optimal Consumption: At the point of consumer equilibrium, the consumer's choices result in the highest level of satisfaction (utility) possible, given their income and the prices of goods. The consumer does not have an incentive to reallocate their budget because doing so would reduce their overall utility. Economics for Engineers 31 Graphical Representation: Consumer equilibrium is often depicted on a graph, with the X-axis representing the quantity of good X and the Y-axis representing the quantity of good Y. The budget constraint is a straight line that represents the combinations of goods the consumer can afford. The highest attainable indifference curve (representing the highest level of satisfaction) is tangent to the budget constraint. The point of tangency is the consumer equilibrium. Shifts in Consumer Equilibrium: Consumer equilibrium can change due to various factors, including changes in income or the prices of goods. An increase in income shifts the budget constraint outward, allowing the consumer to afford more goods. A decrease in income shifts the budget constraint inward. Changes in the prices of goods also affect consumer equilibrium. An increase in the price of one good makes it relatively less affordable, shifting the consumer's choices towards the other good. A decrease in the price of one good makes it relatively more affordable, influencing the consumer's allocation of their budget. In summary, consumer equilibrium is the point at which a consumer maximizes their utility by allocating their limited income to purchase goods and services. It is achieved when the marginal utility per dollar spent on each good is equal, while staying within the budget constraint. Understanding consumer equilibrium is essential for analyzing consumer behavior, price changes, and income changes in microeconomic decision-making. Demand Forecasting: Regression Technique Demand forecasting is a crucial process for businesses to predict future customer demand for their products or services. Accurate demand forecasting helps companies optimize inventory, production, and distribution, reducing costs and increasing efficiency. One common technique for demand forecasting is regression analysis. Here's an overview of demand forecasting using the regression technique: 1. Regression Analysis: Regression analysis is a statistical method that examines the relationship between a dependent variable (in this case, demand) and one or more independent variables (such as time, price, marketing expenditures, or other relevant factors). Economics for Engineers 32 In demand forecasting, regression analysis can help identify the factors that significantly influence demand and quantify their impact. 2. Types of Regression Models: Simple Linear Regression: This model assumes a linear relationship between demand and one independent variable (e.g., time). The equation for simple linear regression is often written as: Demand = a + b * Time, where "a" is the intercept and "b" is the slope. Multiple Linear Regression: In this model, multiple independent variables are used to predict demand. For example, you might use price, advertising expenditure, and time to predict demand. The equation takes the form: Demand = a + b1 * Price + b2 * Advertising + b3 * Time. Non-Linear Regression: Sometimes, the relationship between demand and independent variables is not linear. In such cases, non-linear regression models are used to capture more complex relationships. 3. Data Collection: To perform regression analysis for demand forecasting, you need historical data on both the dependent variable (demand) and the independent variables (e.g., time, price, marketing expenditure). The quality and quantity of data are crucial for accurate forecasts. 4. Model Building: You can use statistical software or tools like Excel, Python, R, or specialized demand forecasting software to build regression models. The software will help you estimate the coefficients (a and b) that define the relationship between demand and the chosen independent variables. 5. Model Validation: After building the regression model, you should validate its accuracy and reliability. You can use statistical measures such as R-squared (R²), mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), or root mean squared error (RMSE) to assess the model's goodness of fit and predictive accuracy. 6. Forecasting: Once you have a validated regression model, you can use it for demand forecasting. Simply input the relevant values of the independent variables (e.g., future time periods, prices, marketing budgets) into the model to predict future demand. Economics for Engineers 33 7. Interpretation: Regression analysis also provides insights into which independent variables have the most significant impact on demand. This can help businesses make informed decisions about pricing strategies, marketing campaigns, and other factors affecting demand. 8. Continuous Monitoring: Demand forecasting is an ongoing process. You should continually monitor and update your regression model as new data becomes available and market conditions change. Benefits of Regression Technique in Demand Forecasting: Provides a systematic and data-driven approach to demand forecasting. Quantifies the impact of various factors on demand. Allows for the incorporation of multiple independent variables. Helps businesses make informed decisions regarding pricing, inventory, and marketing strategies. Can be adapted for both short-term and long-term forecasting. Challenges: Assumptions: Regression models assume a linear relationship between variables, which may not always hold true. Data Quality: The accuracy of demand forecasting heavily depends on the quality and completeness of historical data. Model Complexity: Building and interpreting regression models may require statistical expertise. External Factors: Regression models may not account for unforeseen external factors, such as economic shocks or political events. In summary, demand forecasting using the regression technique is a valuable tool for businesses to predict future demand based on historical data and relevant independent variables. When properly applied and validated, regression analysis can improve decision-making and efficiency in various industries. Time-Series Forecasting Economics for Engineers 34 Time-series forecasting is a statistical technique used to make predictions or forecasts based on historical data points collected over time. This approach is particularly useful when dealing with data that is chronologically ordered, such as daily stock prices, monthly sales figures, or annual weather patterns. Time-series forecasting can help businesses and researchers predict future trends, identify patterns, and make informed decisions. Here are the key components and methods used in time-series forecasting: Components of Time-Series Forecasting: 1. Time-Series Data: Time-series data is a sequence of data points collected at regular time intervals, such as daily, monthly, or yearly. Each data point represents a measurement or observation made over time. 2. Dependent Variable: The variable of interest, which is observed over time and is the focus of the forecasting. It could be anything from stock prices to temperature readings. 3. Independent Variables: These are factors or variables that can influence the dependent variable. In time-series forecasting, these are often referred to as exogenous variables. For example, factors like marketing spend, holidays, or economic indicators can affect sales figures. Time-Series Forecasting Methods: There are several methods for time-series forecasting, and the choice of method depends on the data and the specific forecasting task. Some common techniques include: 1. Moving Averages: This method calculates the average of the most recent data points within a fixed time window. Moving averages smooth out short-term fluctuations and highlight longer-term trends. There are different variations, including simple moving averages, weighted moving averages, and exponential moving averages. 2. Exponential Smoothing: Exponential smoothing assigns exponentially decreasing weights to past observations, giving more weight to recent data. This method is useful for capturing trends and seasonality. 3. ARIMA (AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average): ARIMA is a widely used time-series forecasting model that combines autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) components. It also includes differencing to make the data stationary. ARIMA models are effective for a wide range of time-series data. Economics for Engineers 35 4. Seasonal Decomposition of Time Series (STL): STL decomposes a time series into three components: seasonality, trend, and remainder (residual). This method can help capture the underlying structure of a time series. 5. Prophet: Prophet is a forecasting tool developed by Facebook that is useful for handling time series with daily observations and seasonal patterns. It can capture holidays and special events. 6. Machine Learning Models: Machine learning techniques, such as neural networks, support vector machines, and random forests, can be applied to timeseries forecasting. These models are often used when dealing with complex data patterns. 7. State Space Models: State space models, including the Kalman filter and Bayesian structural time series (BSTS), are advanced methods that can capture complex time-series structures. Steps in Time-Series Forecasting: 1. Data Collection: Gather historical time-series data that represents the variable of interest, along with any potential independent variables or exogenous factors. 2. Data Preprocessing: Clean the data, handle missing values, and transform it to be suitable for modeling. This may include differencing to make the data stationary. 3. Model Selection: Choose an appropriate forecasting method based on the data and the specific forecasting task. 4. Model Training: Use historical data to estimate the parameters of the selected forecasting model. 5. Model Evaluation: Assess the model's performance using appropriate evaluation metrics, such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Mean Squared Error (MSE). 6. Forecasting: Apply the trained model to make future predictions and generate forecasts. 7. Model Updating: Continuously update the model as new data becomes available, improving forecasting accuracy. Time-series forecasting is widely used in various domains, including finance, economics, climate science, and supply chain management, to make predictions and decisions based on historical data patterns. The choice of the forecasting method Economics for Engineers 36 and approach depends on the nature of the data and the specific objectives of the forecasting task. Smoothing Techniques: Exponential Moving Averages (EMA) and Moving Averages (MA) Method Smoothing techniques, such as Exponential Moving Averages (EMA) and Moving Averages (MA), are methods used in time-series analysis to reduce noise in data and identify underlying trends or patterns. These techniques are particularly helpful for making data more interpretable and for forecasting future values based on historical data. Let's explore both methods: 1. Moving Averages (MA): Moving averages (MA) is a simple and widely used smoothing technique that calculates the average of a specified number of previous data points to create a Economics for Engineers 37 smoother representation of the time series. There are two main types of moving averages: Simple Moving Average (SMA): This method calculates the mean of a fixed number of past data points. For example, a 10-day SMA calculates the average of the most recent 10 data points. Weighted Moving Average (WMA): In this method, different weights are assigned to past data points, with more recent data points typically given higher weights. WMA allows more responsiveness to recent changes in the data. Advantages of Moving Averages: Simple to implement and understand. Effectively reduces noise and highlights trends. Useful for identifying cyclical patterns in data. Disadvantages: It can lag behind significant changes in the data because it relies on past observations. The choice of the moving average period is somewhat arbitrary and can impact the results. 2. Exponential Moving Averages (EMA): Exponential Moving Averages (EMA) is a more advanced smoothing technique that places more weight on recent data points while still considering older data. This method is more responsive to recent changes and can adapt quickly to shifts in the data. The EMA is calculated using the following formula: EMA (today) = (Price (today) * Smoothing Factor) + (EMA (yesterday) * (1 Smoothing Factor)) Where: EMA (today) is the EMA value for the current period. Price (today) is the value of the time series at the current period. EMA (yesterday) is the EMA value for the previous period. The Smoothing Factor is a value between 0 and 1, with a higher value giving more weight to recent data points. Advantages of Exponential Moving Averages: Economics for Engineers 38 More responsive to recent changes in data. Reduces lag and captures trends more quickly. Suitable for time-series data with changing dynamics. Disadvantages: May be overly sensitive to noise in very short time frames. Requires the selection of a smoothing factor, which can impact the results. Applications: Both MA and EMA methods are applied in various domains, including finance, supply chain management, and economics, to smooth time-series data and make forecasts. They are used for tasks like predicting stock prices, sales forecasts, and demand planning in businesses. Choosing Between MA and EMA: The choice between MA and EMA depends on the specific characteristics of the data and the forecasting objectives: Use MA when a simple and smoothed representation of data is required, and you want to reduce noise and emphasize longer-term trends. Use EMA when you need a more responsive technique to quickly adapt to recent changes in data and capture short-term trends. EMA is useful when you want to give more importance to recent observations. In practice, analysts often experiment with different methods and parameters to determine which approach works best for a particular dataset and forecasting task. made with chatgpt by yashs so content may be wrong Economics for Engineers 🙂 39