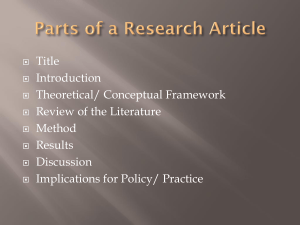

Week 1 Course intro, developing a RQ, translating RQ into conceptual model Summary chapter 1,4,5 : BOOK Academic Skills for Interdisciplinary Studies (GPK) Chapter 1 Preparatory reading and researching An initial literature search The objective of a literature review is to find academic sources that help you to map out the concepts, theories and empirical studies that are relevant to your topic. Objective is two-fold: (1) Find as much as possible about the research field. (2)(on the other hand) tap into unexplored field • • Theories: are supposed relationships between concepts Concept: an abstraction, supposed pattern, or idea that can be defined or combined in different ways. • Correlation: Link between two concepts; for example, if concept A is measured somewhere, and concept B is also measured. • Causal relationship: concept A explains the presence of concept B. è Thus concepts are the building blocks of theories. Definitions (and theories about the supposed relationship between them) can differ significantly across the disciplines and between scholars. • Academic articles (Scholarly literature) share a number of characteristics: o Published in Scholarly journals § Measure a journal’s value with its impact factor (number of citations of its articles in other scholarly articles.) o Journals are Peer-reviewed (their content is assessed by at least two independent and usually anonymous scholars) o Articles are written by authors who have no direct commercial or political interest in the topic on which they are writing, and the authors’ background is given. o Articles are preceded by an abstract. o Articles contain a large number of references to other scholarly publications on the same topic. Grey literature Grey literature à publications written by researchers or research organizations, but not peer-reviewed. Grey literature frequently contain specialized and specific knowledge that is not available in academic publications. Difficult to gauge whether these articles are of sufficient quality to be used as reliable sources. • Include o Advisory reports o Non-academic research reports o Non-academic (or yet-to-become academic) publications from the academic world o Popular scientific books Digital search engines and databases Various databases and search engines can be used to search scholarly journals. Search methods Tips for searching for literature: 1. Use a combination of search terms that accurately describes your topic. 2. You should used mainly Engilsh search terms. 3. Try multiple search terms to unearth the sources you need. a. Ensure that you know a number of synonyms for your main topic b. Use the search engine’s thesaurus function (if available) to map out related concepts. Ordering you search results It is often possible to order your search results in different ways. Examples: • • • Date of publication Relevances: the articles at the top of the list are those closest to your search terms. References: (most useful): the articles at the top of the list are those that are used most often by other authors and best reflect the key debates and research in the field you’ve identified. Continuous search Use your search results to find more relevant sources. 1. Use the overview of keywords (of the article you already found) to help you to refine or improve your search combination. 2. Look at which recent articles refer to a particular article that you’ve already found. 3. Use the option ‘related articles’, these literatures suggestions can also help you when searching for other relevant sources. Chapter 4: From your topic to your question Defining your topic is a dynamic process. Concepts and theories can provide a good indication, however, as you can narrow or widen the scope by limiting or expanding the network of related concepts. It is the task of the researcher to take a clear position amongst the jumble of conflicting or complementary theories. This is often done in the theoretical framework. It is insufficient to have an understanding of the existing theory. This is known as the problem statement: a statement of what, based on the theory, has yet to be clarified about the topic, and why it is essential to investigate this. Based on this statement, you will finally be able to formulate your research question: the question that will shape the rest of your research. Theoretical framework Theoretical framework can differ from study to study. There are disciplines that do not approach theory as it is conceived here, namely as theory in empirical scholarship: a relationship between concepts. Aside from precisely which theoretical frameworks is used, studies can also differ in terms of the role the theoretical framework plays within them: • • • Purely methodological papers: the theoretical framework mainly indicates the state of existing research in a field. Conceptual-theoretical studies: frequently omit the ‘debate’ between different theories, because this is already covered in the research. Empirical cycle (in this books): the theoretical framework plays a prominent role in this, because it not only outlines the state of the research field, but it also demarcates the niche where you, the researcher, are intending to contribute to knowledge in one or more research fields. From theories to concepts and dimensions In order to find your niche, you must look at what other researchers have done, first broadly (broad theoretical basis) and you try to keep narrowing it down until you identify the aspects of a theory that is relevant to describing and/or explaining your case. Based on your exploratory literature review, you built up a picture of the key authors and their most important articles. For a research study in which you want to generate your own results, the topic needs to be narrowed down further – to identify a gap in the existing knowledge. A way to find a ‘niche’ in your chosen research field is to keep investigating which dimensions (scope) of the concepts are identified by the different authors. Identifying the different dimensions helps you to define which aspects of the concept you want to measure and which you do not. The theoretical framework and interdisciplinary research When you do interdisciplinary research, your theoretical framework is where you link several theoretical perspectives together; it is where you describe how different disciplines approach similar concepts differently. The problem statement The theoretical framework ends with the establishment of the knowledge gap; in the problem statement you argue why this gap should be filled with your study. Two factors are important in this: scholarly and social relevance. • • Scientific relevance: the value that your research will add to existing scientific practice. Socially relevant: your research findings should be of interest to society in a broad sense. Chapter 5: Formulating a good question Drafting a good research question is one of the most difficult, but also one of the most important , aspects of academic research. It is an iterative process in which you go back and forth between the literature and your research question. Checklist for research: - Relevance Precision Feasibility Position within field There roughly two sorts of questions: 1. Comparative questions – These are questions whereby you compare two or more concepts, or look at the relationship between them. 2. Explanatory questions – you try to unravel the explanations that underlie a phenomenon, something that is particularly common in literature reviews. When formulating your question, anticipate the type of answer that will follow. In addition, it is very important to delimit your question. In other words, the terms and concepts that make the question should be defined as clearly and specifically as possible, so that it is clear exactly what you want to research. Another option is to specify these dimensions in sub-questions. In this case, you take a main question and divide it into sub-questions. You then address the answers to the sub-questions in the conclusion. The answers to the sub-questions answer the main questions. Week 2 Embedding RQ into literature Lecture 2 – PowerPoint Research paper process All steps of a scientific research process • • • • • Introduction/research questions Literature review Research method Data analysis Conclusion, Discussion Scientific Research Stars with a Hourglass model à the research starts really broad and then you narrow it down to a question or problem that fits in your scope. You choose a subject and keep it (broad). Then you scope it down to find a relationship between the things you want to study (Small). Then you suggest that it can be useful for a broader scope (broad). The research question is key as it determines: • • • • • Overall focus Literature review Methodology Analysis Reporting What is a research question? • • A research question is a question that a study or research project aims to answer. The research question arises from the identified problem o Research questions identify the information that is needed to solve the central problem o Sub-question for a research question are interrelated o Together, they will provide an answer for you central problem o “how is concept X defined?” is NOT a research question! How to write a research question: from topic to specific question 1. Start with an interesting topic à a gap in literature 2. Do preliminary research à look on google scholar if there are important topics/subjects for this topic 3. Focus on specific question à Narrow the question down so it is feasible à write out scope and conceptual model (moderators/mediators) à maybe even know similar topics that have not the same definition. E.g. bullwhip effect but not ….. 4. Evaluate à Identify a research problem ‘what happens if there is a negative relation?’ e.g. sales lead to less expected profit due to bullwhip effect. Not every research question is a good research question!! Characteristics of a strong research question 1. 2. 3. 4. Focused and researchable (measurable) Specific and feasible (redelijk) Complex and arguable Original and relevant Steps before you finalise your RQ? • Know about the scope of your research o Which concepts and variable will be included? o What will NOT be included? o Fit with the research goal o Consider the type of research (collecting original data, analyzing existing data, etc.) • • • In most studies, the research question is written so that it outlines various aspects of the study, including o The population o Variables to be studied (the core concept) o The problem the study addresses These questions are dynamic; this means researchers can change or refine the research question as they review related literature Does your Thesis have single or multiple Research Questions (sub-questions) In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables. è Restate your question as a Thesis Statement There are different types of Research Questions • • • Descriptive Questions: Questions that seek to explain something. Typically start with phrases like “What are/is”, How..?” and “What amount…?” Comparison Questions: Questions that focus on the relationship between variables: they focus on the differences and similarities between these variables Causal Questions: Questions that examine whether one variables has impacted another. Finally, the problem statement should frame how you intend to address the problem. Your goal should not be to find a conclusive solution, but to seek out the reasons behind the problem and propose more effective approaches to tackling or understanding it. 1 Independent variables are what we expect will influence dependent variables (X-as) 2 A dependent variable is what happens as a result of the independent variable (Y-as). Generally, the dependent variable is the disease or outcome of interest for the study, and the independent variables are the factors that may influence the outcome. Where do I embed my RQ? Follow the following format: 1. Paragraph 1: The problem – why is the study important and relevant 2. Paragraph 2: What do we know? Acknowledge what others have said about the topic; What don’t we know? What is the gap in the literature? 3. Paragraph 3: This is the research question; and this is how I am going to address it 4. Paragraph 4: summary of the findings 5. Paragraph 5: contributions 6. Paragraph 6: The structure of the paper Everything in your thesis should be linked to the Research Questions. To summarize (lecture 2): 1. Your research question should be embedded in the introduction section of your thesis 2. You may have single or multiple research questions, All the research questions should be linked to each other. 3. It should again be mentioned in the conclusion section of your thesis highlighting whether the evidence provided by your data agrees with your argument/research question? 4. The research question(s) should clearly state your independent1 and dependent2 variables. It should also state the proposed relationship (needless to say this should be based on prior research) between these variables. 5. Thesis writing is a dynamic process; the research question is the key to all the other components of your thesis. For example, the proposed hypothesis is a formal statement (based on your research question) that the researcher sets out to prove or dispose. Summary: BOOK Jaccard, J. & Jacoby, J. 2020. Theory construction and model building skills (JJ) Chapter 4: Creativity and the Generation of Ideas This chapter will provide concrete guidance for theory construction. Theory construction involves specifying relationships between concepts in ways that create new insights into the phenomena we are interested in understanding. In this chapter, we briefly review research on creativity to give you perspectives on the mental and social processes involved in the creative process. One small step for science The gradual building of knowledge is an essential aspect of the scientific endeavor. Small bits of knowledge cumulate into larger groupings of knowledge. Creativity Creativity can be defined as the ability to produce work that is both novel (original and unexpected) and appropriate (useful or meets task constraints). Creative contributions result from the interaction of three systems: 1. The innovating person 2. The substantive domain in which the person works 3. The field of gatekeepers and practitioners who solicit, discourage, respond to, judge, and reward contributions. Creative ideas provide novel perspectives on phenomena in ways that provide insights not preciously recognized. Ideas differ in their degree of creativity, with some ideas being extremely creative and others only marginally so. But just because an idea is “crowd defying” does not make it useful. For creativity to occur in science, it typically is preceded by a personal decision to try to think creatively. Choosing what to theorize about The first step in building a theory is choosing a phenomenon to explain or question/problem to address. Be careful about selecting areas that are too broad and abstract. It is one thing to try to solve an existing problem or answer an existing question, but creative scientists also identify new problems to solve or new questions to answer. Literature reviews Perhaps the most often recommended strategy for gaining perspectives on a phenomenon or question/problem is to consult the scientific literature already published on the topic. Heuristics for generating ideas We now turn to specific strategies you can use to think about issues in creative and novel ways. The book present 27 heuristics: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Analyze your own experiences Use case studies Collect practitioner or expert rules of thumb Use role playing Conduct a thought experiment Engage in participation observation 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. Analyze paradoxical incidents Engage in imaging Use analogies and metaphors Reframe the problem in terms of the opposite Apply deviant case analysis Change the scale (imagining extreme changes as a method of stimulating thinking Focus on processes or focus on variables Consider abstractions or specific instances Make the opposite assumption Apply the continual why and what Consult your grandmother – and prove her wrong Push an established finding to the extremes Read biographies and literature Identify remote and shared/differentiating associates Shift the unit of analysis Shift the level of analysis Use both explanations rather than one or the other Capitalize on methodological and technological innovations Focus on your emotions Find what pushes your intellectual hot bottom Engage in prescient theorizing Scientists on scientific theorizing Chapter 5: Focusing Concepts People see the world not as it is, but as they are. – Albert Lee When formulating a theory, researchers usually begin with some phenomenon that they want to understand. In chapter 5, we focus on strategies for specifying and refining conceptual definitions for those concepts that one decides to include in the system. We begin with the describing the process of instantiation … The process of instantiation The process of instantiation is a method for making abstract concepts more concrete. In the process of theorizing, scientists usually try to strike a balance between being too specific and being too abstract, to the point where the concepts become “fuzzy” and unmanageable. • Instantiation o a deliberate process that involves specifying concrete instances of abstract concepts in order to help clarify their meaning. § Goal: refine fuzzy concepts o Is a bridge between the conceptual and the empirical realms where the validity of a theoretical expression is subjected to empirical testing. § Goal: make the theory testable • Hypothesis o Refer to the specific empirically based instances that are used to test a more general theoretical expression. o Consist of concepts and relationships The nature of conceptual definitions The outcomes of instantiation are termed conceptual definitions, which represent clear and concise definitions of one’s concept. Not only do abstract constructs have to be defined as precisely as possible, but even seemingly obvious concepts frequently require explanation. Shared meaning, surplus meaning, and nomological networks Shared meaning à The extent to which conceptual definitions overlap in different theories. (The points of agreement in a conceptual definition my be assumed to represent the essential core of the concept.) Surplus meaning à those portions of conceptual definitions that do not overlap across theories. (Can be contrasted with the remainder, the disagreements of conceptual definitions in research). Nomological networks à the meaning and utility of a concept emerge in the context of the broader theoretical network in which the concept is embedded. Although it is desirable for constructs to have shared versus surplus meaning, the worth and meaning of a construct ultimately are judged relative to the broader nomological network in which the construct is embedded. Practical strategies for specifying conceptual definitions • • • • • • • • • Examine the scientific literature to see how other scientists have done so Consulting a dictionary List the key properties of a concept o Properties à the identifiable characteristics of concepts and form the cornerstone for later measurement of the concept and empirical testing. Ask the question “What do you mean by that?”, focus on the keywords within the answer and ask again the same question. Play the role of a journalist who must explain the nature of the varable and its meaning to the public. Place yourself in the position of having to define and explain the concept to someone who is just learning the English language. Using a denotive definition strategy Writing out how the concept would be measured in an empirical investigation. Use principles of grounded theory construction. Multidimensional constructs When defining concepts in a theory, it sometimes is useful to thing of subdimensions or “subtypes” of the construct. A construct is multidimensional when it refers to several distinct but related dimensions treated as a single concept. Example, risk taking have delineated four types of risk taking propensities of individuals: (1) physical risk taking, (2) social risk taking, (3) monetary risk taking and (4) moral risk taking. You can often make a theoretical network richer and concepts more precise and clearer by specifying subcomponents or dimensions of a higher-order construct. Creating constructs Social scientist use a variety of strategies for “creating” variables. There are different strategies to do that: 1. Translate an individual-level variable into a contextual-level variable. a. Example: ethnicity. Researchers can characterize ethnicity at higher contextual levels, such as the ethnic composition of a school that individuals attend. 2. Reframe environment or contextual variables to represent an individual’s perceptions. a. Instead of studying the characteristics of the organizational climate of a business, you might study how an individual perceives the organization climate. Operationism Conceptual definition specify what needs to be assessed in empirical science, but the matter of how they will be assessed is a distinct issue. This latter function is served by what scientists refer to as operational definitions, which are central to the design of empirical tests of a theory. Many behavioral scientist felt we should abandon conceptual definitions and restrict science to observable operations. This approach was called operationism. Article: What Constitutes a Theoretical Contribution (Whetten) There are several excellent treatises on the subject, but they typically involve terms and concepts that are difficult to incorporate into everyday communications with authors and reviewers. My experience has been that available frameworks are as likely to obfuscate, as they are to clarify, meaning. What are the building blocks of theory development? What and How describe; only Why explains. What and How provide a framework for interpreting patterns, or discrepancies, in our empirical observations. According to theory development authorities (Dubin, 1978), a complete theory consists 3 elements: - What How Why (Describe) (Describe) (Explain) (Dependent and independent variables) (Arrows show effect) (Literature review backing) What Which factors are part of the explanation? Two criteria: 1. Comprehensiveness (are all relevant factors included?) 2. Parsimony (should some factors be deleted because they add little value?) Rule of thumb: better to add in too many than too little factors. Refining will erase useless factors lateron How How are these factors related? (with arrows from independent to dependent. Can be: +, -, unknown) ‘What’ and ‘How’ crafts the conceptual framework basically. Just a visual tool, not mandatory Why (most important aspect of building blocks) Justify selection of the (‘what’) criteria. Order triumphs over data when creating a theory development. As a researcher, you have to convince stakeholders that there is a ‘logical’ effect between two variables. If all the relationships have been proven, the theory/model is created for classroom. If not, the ‘laboratory’ can still play with the variables and knowledge. The goal is to extend existing knowledge, not rewrite it (in majority of cases). This is the reason for the importance of the ‘why’. This is an important distinction because data, whether qualitative or quantitative, characterize; theory supplies the explanation for the characteristics. Therefore, we must make sure that what is passing as good theory includes a plausible, cogent explanation for why we should expect certain relationships in our data. Together these three elements provide the essential ingredients of a simple theory: description and explanation. There are three conditions: (Moderators for example: this is only applicable in industry X for example) - Who Where When These conditions place limitations on the propositions generated from a theoretical model. These temporal and contextual factors set the boundaries of generalizability, and as such constitute the range of the theory. What is a legitimate value-added contribution to theory development? Most scholars will add on existing knowledge instead of being the new Einstein. What and How. Adding or erasing a factor to a consisting framework is not considered to be theoretical enough. If you want to add or change a current framework, the ‘how’ in your analogy is very important. “Science is fact, just as houses are made of stone… …yet a pile full of bricks is not a house and a collection of facts is not necessarily science”. Therefore, theoretical insights come from demonstrating how the addition of a new variable significantly alters our understanding of phenomena by recognizing our casual maps. The ‘why’ is pretty hard to make factual, since it often requires perspectives from other fields. This is the most difficult one and generally precipitates reconceptualization of affected theories. It is insufficient to point out the limitations in current conceptions of a theory’s range of application. There is an upside to applying old models to new settings: the feedback loop. Researchers learn new elements of the model, which should improve it overall. Moreover, applying an old model in a new setting and showing that it works is not intrusive in itself. Preferably, investigate qualitative changes in the boundaries of a theory rather than quantitative expansions. (Basically, adjust the model and explain why it does / does not work in setting X as well) Three broad themes underline this section: 1) Theoretical critiques should focus on multiple elements of the theory 2) Theoretical critiques should assemble and arrange compelling evidence (S.O.U.R.C.E.!) 3) Theoretical critiques should propose remedies or alternatives (only critiquing leaves no room for comparison) What factors are considered in judging conceptual papers? What, how and why are the building blocks but there are also other relevant factors that make a paper from good to great: -Clarity of expression -Impact on research -Timeless -Relevance The following 7 key-factors, in order, cover substantive issues: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) “What’s new?” “So what?” “Why so?” “Well done?” “Done well?” “Why now?” “Who cares?” Which value added? (Scope and degree) Practicable in organizational science? (Not just fun on paper) Logic and evidence compelling? Completeness + thoroughness Paper well written? (Lay-out as well as content itself) What will it do with the previous knowledge? Demographic/Audience? Week 3 Writing the introduction/Theory section Lecture 3 - Powerpoint Scientific research Hourglass model • • • • • • Introduction à o describe the definition of your important keywords o Highlight the relevance of your study Literature review Hypotheses & conceptual model Method Results Conclusion & Discussion When you have your research question (lecture 2) ask yourself: why is it important to answer the research question? For this there are two sub-steps you can use: o o Add a description of relevance à Why do we want to know…. Add a summary of relevant theory à Because we know little about … Toulmin method • A claim is the assertion that authors would like to prove to their audience. It is, in other words, the main argument. • The grounds of an argument are the evidence and facts that help support the claim. • Finally, the warrant, which is either implied or stated explicitly, is the assumption that links the grounds to the claim. • Backing refers to any additional support of the warrant. In many cases, the warrant is implied, and therefore the backing provides support for the warrant by giving a specific example that justifies the warrant. • The qualifier shows that a claim may not be true in all circumstances. Words like “presumably,” “some,” and “many” help your audience understand that you know there are instances where your claim may not be correct. • The rebuttal is an acknowledgement of another valid view of the situation. Including a qualifier or a rebuttal in an argument helps build your ethos, or credibility. When you acknowledge that your view isn’t always true or when you provide multiple views of a situation, you build an image of a careful, unbiased thinker, rather than of someone blindly pushing for a single interpretation of the situation. Writing the introduction • Follow the following format: 1. Paragraph 1: The problem – why is the study important and relevant. Give key definitions. 2. Paragraph 2: what do we know? Acknowledge what others have said about the topic. 3. Paragraph 3: What don’t we know? What is the gap in the literature? 4. Paragraph 4: This is the research question; and this is how I am going to address it. • All the paragraph should be linked and interesting (so that the reader becomes interested) 5. Paragraph 5: This is what I found, and this is why it matters. Contribution of the study. 6. Paragraph 6: The structure of the paper (literature review, methods, findings, discussion, conclusion). Literature review A Literature review shows the current state of the research: cite all papers used to answer the RQ and write down all theories to prove the information. Important: every statement should have a citation in the text that is linked to the bibliography. • • • • • Is guided by the research question Defines and clarifies the issue(s) or problem(s) specified Summarizes previous investigations in order to inform the reader of the state of current research Leads to conceptual frameworks Something you do as well as something you write Aim of the literature review 1. Introduction establishing purpose 2. Body analyzing the literature 3. Conclusion summarizing key findings Format of a literature review Reviewing the literature and selecting sources • Literature search o Obviously, a systematic literature search is key § Note down the keywords you use to search. Use your subject words/conceptual model words. § You may need to use a database. § Your thesis should mainly be based on academic sources. § Include references as your write. § There are no guidelines as to how many papers to read. Article: What Theory is Not (Sutton & Staw, 1995) This essay describes differences between papers that contain some theory rather than no theory. There is little agreement about what constitutes strong versus weak theory in the social sciences, but there is more consensus that references, data, variables, diagrams, and hypotheses are not theory. Despite this consensus, however, authors routinely use these five elements as theory. We explain how each of these five elements can be confused with theory and how to avoid such confusion. There is confusion because of different reasons: 1. Lack of consensus on exactly what theory is, hinders the development of strong theory 2. Editors or reviewers might reject a well-articulated theory that fits the data based on their own tastes. 3. The process of building theory is itself full of internal conflicts and contradictions. We explain why some papers, or parts of papers, are viewed as containing no theory at all rather than containing some theory. Five elements: 1. References are not theory: using references (so mentioning facts) does not immediately contribute to a good research if you don’t explain the arguments behind it. Authors need to explicate which concepts and causal arguments are adopted from cited sources and how they are linked to the theory being developed or tested. à ask HOW 2. Data are not theory: Empirical results can certainly provide useful support for a theory. But they should not be construed as theory themselves. Prior findings cannot by themselves motivate hypotheses, and the reporting of results cannot substitute for causal reasoning. à ask WHY? 3. Lists of variables or constructs are not theory: A theory must also explain why variables or constructs come about or why they are connected. à WHY 4. Diagrams are not theory: Diagrams or figures can be a valuable part of a research paper but also, by themselves, rarely constitute theory. 5. Hypotheses (or predictions) are not theory: a list of hypotheses cannot substitute for a set of logical explanations. EXTRA From test exam: We argue that when customers are presented with a brand that has a good reputation, customers are more likely to purchase that brand’s products. While there hasn’t been any empirical work on the subject, we argue that this relationship exists based on the fact that most reputable marketing scholars think this might be the case (Hawabhay, Abratt & Peters 2009, Teas & Agarwal 2000). 10) Which of the following statements is true? I. This is an invalid argument, on the grounds that this is ‘an appeal to authority’ II. This is an invalid argument, on the grounds of arguing by ‘majority view’ a. Only statement I is correct b. Only statement II is correct c. Both statement I and statement II are correct d. Neither statement is correct Appeal to authority à false validity because of thinking someone with authority did or said something so it should be right. Majority view à false validity because a group says it, it can still be wrong. Making consensus explicit (identifying strong theory) ‘Strong theory, in our view, delves into underlying processes so as to understand the systematic reasons for a particular occurrence or non-occurrence’. As Weick (1995) put it succinctly, a good theory explains, predicts, and delights. Journals facilitate stronger theory & reconsider their empirical requirements Some prominent researchers have argued the case against theory. There is a lot of bad or mediocre theory written in papers. 2 important aspects: theory testing and theory building. Most of the papers don’t include both as these are contradictory requirements. Some review parties like ASQ want to bridge the gap between these 2 aspects. They ask authors to engage in creative, imaginative acts. On the other hand, ASQ wants these same authors to be precise, systematic, and follow accepted procedures for quantitative or qualitative analysis. Most of the contributors to our field’s research journals are rarely skilled at both theory building and theory testing. Companies like ASQ that review the paper will mention the critique. The result is usually an author who either dutifully complies with whatever theoretical ideas are suggested or who becomes so angered that he or she simply sends the paper elsewhere. By going through rounds of revision, a manuscript may end up with stronger theory, but this is not the same as saying that the authors have actually learned to write better theory. Learning to write theory may or may not occur, and when it does occur, it is almost an accidental byproduct of the system. The result of this behaviour of reviewing companies is that contradictory demands for both strong theory and precise measurement are often satisfied only by hypocritical writing. Theory is crafted around the data. The author is careful to avoid mentioning any variables or processes that might tip off the reviewers and editors that something is missing in the article. Peripheyal and intervening processes are left out of the theory so as not to expose a gap in the empirical design. We are guilty of these crimes of omission. So its not that researchers are interested in the study and set goals to prove the study, BUT they measure things and adapt concepts and arguments to support the measurements as they are afraid that reviewing companies otherwise would decline their papers. We argue that journals ought to be more receptive to papers that test part rather than all of a theory and use illustrative rather than definitive data. Our recommendation is to rebalance the selection process between theory and method. People's natural inclination is to require greater proof of a new or provocative idea than one they already believe to be true (Nisbett and Ross, 1980). New ideas are difficult as they require more prove. Some recommendations Our recommendation is to rebalance the selection process between theory and method. We need to recognize that major contributions can be made when data are more illustrative than definitive. If theory building is a valid goal, then journals should be willing to publish papers that really are stronger in theory than method. Authors should be rewarded rather than punished for developing strong conceptual arguments that dig deeper and extend more broadly than the data will justify. We need to be as careful in not overweighting the theoretical criteria for qualitative papers as in underweighting the theoretical contributions of quantitative research. A small set of interviews, a demonstration experiment, a pilot survey, a bit of archival data may be all that is needed to show why a particular process might be true. Subsequent research will of course be necessary to sort out whether the theoretical statements hold up under scrutiny, or whether they will join the long list of theories that only deserve to be true. A lot of small value adding papers can lead to great theoretical development in the end. Summary chapter 9 : BOOK Academic Skills for Interdisciplinary Studies (GPK) Chapter 9: the structure of your article Argumentation structure The argumentation structure is the backbone of your text and the path that you, the writer, mark out for the reader. Establishing a clear structure before you start writing can make it easier to stick to the line of the argument (and you will become less lost in the details). It also becomes easier to see which parts you can delete and where there are still holes in your argument. Objections As the author of a text, it is therefore wise to reflect on potential objections, because refuting (or even negating) them can strengthen your position Framing an argument: Pitfalls Circular reasoning Appeal to an authority Description When you repeat your position rather than substantiating it with an argument The fact that an authority takes a particular position on a certain issue is not in itself a sufficient guarantee that the argument holds. You will have to explain Example For example, if you say that a plan is bad, ‘because it is simply no good’ This theory is correct (Author A, 2011) The majority view why the expert takes this position. If many people, or the majority of a group of people, hold a particular opinion or take a particular position, this does not mean that it is right For example, even if the majority of the population thinks that parliamentary democracy is the best form of government, this is not indisputably true For example, if research shows that rich people are on average happier than poor people, you cannot conclude that money makes people happier. Other factors may be at play, and you could also argue it the other way around: it might be that someone’s level of happiness influences their economic success For example, if a lot of research shows that disarming the Middle East would lead to peace, you cannot conclude from this that if there is no disarmament, there will certainly be no peace. There are also other ways of achieving peace For example: ‘Why does God exist? You prove that God doesn’t exist. False links (spurious correlations) The fact that two things are connected does not automatically mean that one follows from the other. Logical fallacies Conclusions or views that do not follow logically from the arguments that have been discussed Reversing the burden of proof When you claim something, you should be the one to assume the burden of proof for your claim. Saying that someone else should prove the opposite of your claims is misleading and does not substantiate your own view Two opposing options are For example: ‘What would you advanced, while there are in fact rather see covered by medical many more insurance: Viagra pills for macho men or at-home care for old grannies?’ Insinuating that an intervention For example: ‘If we include or measure will take things from Viagra in the basic package for bad to worse, while it is far from medical insurance today, then guaranteed that it will have this tomorrow we’ll be reimbursing effect. breast enlargements. False opposition The slippery slope The structure of a scholarly article à note that this is the same as the empirical cycle You discuss the theory (based on previous research) in the introduction to your article, the testing of the data in the middle section, and the conclusion and evaluation in the discussion section. This division is known as the IMD structure (Introduction – Middle section – Discussion). It can generally be said that the IMD structure is based on the ‘hourglass model’. Introduction (broad) The content of the introduction and the conclusion is broad, In terms of content, the introduction starts broadly and becomes narrower. Structure: Your introduction begins with a broad, general introduction, with the definitions, and an explanation of the concepts that you’re going to investigate. You can also add an hypothesis: what answer can you expect to find, based on the literature? Or provide a brief description of the experimental setup: what is your dependent variable, what is your independent variable, and which indicators are you going to use to test them? After the design section, you can conclude your introduction with a prediction or expectation, whereby you explain what you expect to come out of the variable Middle section (narrow) When doing research, you choose one or more dimensions that fit with your research question. This means that your report becomes substantively narrower, because you can only investigate part of the concept. Structure: write an introductory paragraph every section à then reporting of information/results à possible evaluations can be done while in the process à end with an sub conclusion in every section. Remember to link headings etc. Discussion (broad) In the discussion section, you again formulate the substantive findings more broadly and generally, so that you can nevertheless say something (cautiously) about the whole concept. Structure: Start your discussion with a short summary of the most important results à draw one overarching conclusion from this that directly answers the research question (and sub-questions) à evaluate this conclusion. You can do this by going back to the theoretical framework that you described in the introduction. Does this conclusion support the theory? Why does/ doesn’t it? Eventually you can add starting points for follow-up research in order to complete the empirical cycle, as they count as new observations. Think about if it works in other contexts, etc. Another part that often features in a discussion section is a description of the limitations of the study. The last part that often features is the implications of your study. Recently, there has been increasing emphasis on valorization; politicians highlight its importance and researchers are increasingly being asked how their research results can be valorized. Valorization can be seen as a process of creating social value from knowledge, for example by transforming this knowledge into products, services, processes, and new enterprises Week 4 Methodology: designing your research, collecting data Part 1 video: Qualitative research – Theory about how to do a study Qualitative research Part 1: Doing research The empirical cycle: Part II Research methods Quantitative research versus qualitative research Quantitative research Qualitative research/data Type of data, samples and analysis Numerical data; large random samples; statistical analysis Textual data; small(er) nonrandom samples; qualitative analysis Data sources Structured/closed: e.g. surveys; experiments; simulations; closed interviews; archival data Semi-/unstructured/open: e.g. in-depth, open-ended interviews; observations; documents Relative advantages ‘Statistical generalization’: generalizability to large populations; understanding trends/patterns ‘Analytical generalization’: understanding the level of applicability of theory in different context Relative disadvantages ‘Superficial’: context is less well understood; may affect the validity of results. Difficult to generalize to larger populations. Reliability is more difficult to achieve. The appropriate research method depends on (1 and 2 most important): 1. The nature of your RQ. a. Who/what/where/how many questions à quantitative b. how/why questions à qualitative 2. Extent to which theory is pre-formulated, a. High-very high à Quantitative b. Very low-medium à qualitative 3. Available resources (time, money, help), less resources can lead to more quantitative data. 4. Ease of access to individuals, groups, etc. Part III Designing and conducting high-quality qualitative research: • A. Key characteristics of qualitative research o Rich, in-depth understanding of real-world ‘situations’; individuals’ interpretation and behaviors o Active engagement with people in organizations (or other contexts) o ‘Inductive’ or ‘abductive’ approach (rather than ‘deductive’) o Very suitable for answering ‘how and why’ research questions • B. Designing an conducting high-quality qualitative research: choosing a qualitative research method/strategy for data collection o Important examples of qualitative research methods in business and management research: § Case studies § Action research § Ethnography Case studies à study complex real-life organizational situations over which the researcher has no/little control. Purpose: to make an original contribution to knowledge. Steps in high quality case study research design (Yin): 1. Determining the case study’s questions (how and why) 2. Formulation propositions (proposition used for qualitative research, hypothesis for quantitative research). 3. Selecting cases, choose an event, individual person, group of persons, organizations, group of organizations) etc. 4. Determining data sources and data collection methods 5. Determining the logic linking data to the propositions 6. Determining the criteria for interpreting the findings Types: 1. Abductive: you can have a starting point/theoretical ideas and use data to refine your ideas which can be tested later. You don’t test it yourself. 2. Inductive: study data in a specific context and try to build a theory based on this 3. Deductive: develop hypotheses and testing them Single case: you select an unusual, extreme, revelatory case. Multiple cases: you can adopt replication logic. Literal replication if you see the same research done and you think it will be the same in your setting. Or theoretical replication if you use research that is already done and check to see if it works in your setting as well. Key quality criteria for case study research • • • • Construct validity à are you measuring what you want to measure? Internal validity à explain how one event leads to another, how do we know that the variables are connected? External validity à is the thing I found out also likely to happen in another situation? Generalizability Reliability à if someone does the same study, will he/she come to the same conclusions? Data triangulation is the use of a variety of data sources, including time, space and persons, in a study. -Action research à little from theory little from practice approach. -Ethnography à infiltrating in an organization, really practical approach Part 2 video: practical example of a study (also paper about franchisees & change (Croonen & Brand (2015) à NOTE that it is the conclusion/discussion part from week 7 Introduction the beauty & care cases: it’s about 4 companies selling medicines/health products without prescription from a GP needed. DA/ETOS/Drogist/SPLIT. The companies are based on a franchise business format. Owners have the benefits of the efficient network and processes, in return they pay a percentage of the profit. Following Yins steps in high-quality case study design 1. Determining the case study’s questions (how and why) à Looking at already existing research showed that there was a ‘static view’ on franchisor-franchisee relationships. They made it look like a new owner joined the network and it works well, however there were also disadvantages. There was a lack of knowledge how franchisees respond when they have to adapt major franchisor initiated strategic changes. The goal: to generate/refine theory on antecedents on franchisee responses to franchisor initiated strategic changes. 2. Formulation propositions (proposition used for qualitative research, hypothesis for quantitative research) à No priori propositions but some theory as starting point: agency theory, franchisor control/standardization versus franchisee entrepreneurial autonomy. Readiness to change perspective: expected satisfaction and trust affect change recipients’ responses to change. EVLN (exit, voice, loyalty, neglect): people can engage in different type of ways to ‘problematic events’. Constructive response: Voice/loyalty, Destructive response: exit/neglect. 3. Selecting cases, choose an event, individual person, group of persons, organizations, group of organizations) etc. à Focused on one single case. Purposeful sampling: one ‘extreme case’ due to ‘extreme’ franchisee responses (many ‘exits’). Embedded units in the case: two strategic change processes (SCP1 and 2). Looked at franchisees with a constructive and destructive responses during the SCPs. SCP1 (change 1st attempt): DA felt threat of new competitors selling for lower prices. Therefore they tried adapting B&C’s market positioning and standardisation level. In the end a lot of owners were destructive and the change didn’t really work. SCP2 (change 2nd attempt): There is still tension between desires franchise system standardization (of DA network) and desires for entrepreneurial autonomy (of independent shop owners). This tension becomes even more pressing when a franchisor aims to impose transformational changes that require franchisees to make major financial investments in their businesses and/or to adapt their trade practices. This resulted in 2 ways of responses: Groups: green arrow à theoretical response: there is expected that franchises have different responses (sometimes constructive sometimes destructive). Red arrow à literal replication: there is expected to have franchisees with the same type of reasons for the response. 4. Determining data sources and data collection methods à data triangulation by doing interviews with franchisees. Interviews with CEOs and managers of franchisor. Using written documents: format handbook, strategic plans, year reports, etc. Important for interviews: use the how and why à try to get to know the information they give you After interviews, transcribing and coding interview, three phases: Open coding: making codes directly from the data. Axial coding: reflecting on the open codes: checking overlap and differences. Selective codes: Linking the axial codes to concepts . 5. Determining the logic linking data to the propositions à Asking the owners how did they respond and why? + how their response developed over time. For example you could see that constructive responses had a more positive expected profitability and destructive responses were caused by lower expected profitability attitude. 6. Determining the criteria for interpreting the findings à pattern matching: with expected pattern theory and or rival patterns (alternative explanations). Are there other reasons for franchisee responses? Maybe the researches thought responses could be divided in 2 groups (constructive/destructive) while shop owners had different reasons for responses. The paper is abductive and leaves space for others to test this study. Conclusion: Qualitative research is valuable for obtaining in depth knowledge, by which we can develop/refine theories. However watch out for the risk of ‘data diarrhea’ and you need a clear plan to structure your study and to warrant the quality of the study Week 5 Lecture 5: Introduction to data analysis Data analysis: Regression (in this lecture we only cover regression but there are many other methods). The lecture will talk about the basic only. Key idea 1: Covariation • • Based on advertising o We can (roughly!) predict sales Covariation o Variables ‘move together’ o The stronger the conversation … o … the stronger the relationship o (there is a pattern) o Positive covariation (both variables go up) o Negative covariation (one variable goes up, one variable goes down) Key idea 2: Correlation coefficient • • • • Captures covariance in a number Correlation: between -1 and +1 High values à more closely on a line Only says something about the consistency. Doesn’t distinguish ‘effect size’ from ‘consistency’ Key idea 3: drawing a line • • • • Goal: quantify relationship Simplest method: drawing a line Want to predict sales? Follow the line! Equation: Key idea 4: Steeper lines = stronger relationships Key idea 5: Our model is never perfect R2 • • • • • • How much variation in our data does our model ‘explain’? Relative measure of ‘model quality’ Between 0 and 1 Higher numbers = better model R shows how well the line represents the points Expecting high R2 is usually not realistic Low R vs high R • • Right figure the R is high Left figure the R is low Figure 1: Key idea 5 Key idea 6: uncertainty • • • • • Goal of the research: learn about population o But we have only collected a sample o This gives uncertainty Determined by.. o Sample size § Sampling 10.000 customers: more info than 10 o Variance (spread) § If people vary a lot in their responses, much more likely to sample ‘atypical’ cases Solution: Confidence intervals o Margin of error o We found: § 0,83, unlikely to be exactly 0,83 in population § Cl: [0,73, 0,93] Technical notes: confidence intervals o Usually shown: 95% c.i. § Contains true slope 95% of time. o Also other ci’s available! (e.g. 99% ci) o Method of calculating: too advanced for now o Note on CI vs p-values P-values: hypothesis testing o H1: advertising is (positively) related to sales o The P-value tells you how likely it is that your data could have occurred under the null hypothesis. § A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two phenomena Write down our results • To analyse whether there is a relationship between advertising and sales (=What) • We have performed a regression analysis of advertising on sales (=how) • This regression [was/was not] significant, R2=0.471 F(1.298)=265.1, p=0.000 (=result) • Advertising is significantly related to sales, B=0.826, t-16.28, p=0.000 (=conclusion) ANOVA table in regressions • Tests hypothesis that all coefficients in the model are 0. • Same as previously: we’d like to see low p-values Key idea 7: in moderation, slope depends on a third variable • Allows advertising effects to vary depending on price attractiveness • One equation, but leads to multiple regression lines • Three types of moderation 1. Positive: Effects are strengthened 2. Negative: Effect are weakened 3. Crossover interactions: An initially positive effect turns negative (or vice versa) Writing down our results • To analyze whether price attractiveness moderates the relationship between advertising and sales (=what) • We have performed a moderation analysis • Our results [were/were not] significant • Prices attractiveness positively moderates the effect of advertising on sales. That is, the effect of advertising on sales is stronger at greater levels of price attractiveness (=conclusion). Week 6 Writing a results section Lecture 6 - Powerpoint Results section: structure • So, general structure o What (is our goal)? à is told in introduction § In order to test the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty o How (which technique/approach) We conducted a regression analysis of satisfaction on loyalty o Results (usually: overall model) E.g. group 1 had significance of … and group 2 had a significancy of… o Results i.r.t. hypotheses, and conclusion E.g. based on significancy the results showed that group 1 had more waste then group 2. There was not expected such high significancy for waste…. So our hypothesis…. Also overall result/model fit (r squared test) can be mentioned. • Moderation analysis o What § To analyze whether competition moderates the relationship between product quality and customer loyalty. o How § We have performed a moderated analysis o Results § Our results [were/were not] significant o Res/Conclusion § Competition positively moderates the relationship between product quality and customer loyalty. The effect of product quality on customer loyalty is stronger at greater levels of competition. Papers versus thesis • Paper is constricted to space/words and thesis is not Common mistakes • Things/factors tested that were not in the conceptual model. Stick to what the initial plan was. DON’T change the factors or test different things if there is no significant relationship (called fishing expedition). • Unclear structures/pictures/language. You should walk the reader through the hypothesises in chronological order.