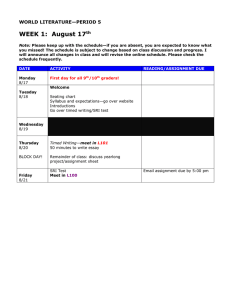

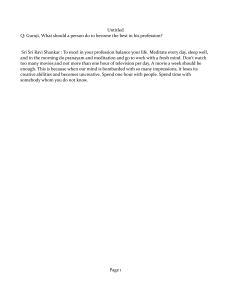

Received: 19 December 2018 Revised: 19 August 2019 Accepted: 16 September 2019 DOI: 10.1002/bse.2393 RESEARCH ARTICLE A systematic literature review of socially responsible investment and environmental social governance metrics Luluk Widyawati UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, UQ St. Lucia, Queensland, Australia Abstract Socially responsible investment (SRI) encompasses both ethical and financial para- Correspondence Luluk Widyawati, UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Level 2, Colin Clark Building (Building 39), UQ St. Lucia, Queensland 4072, Australia. Email: luluk.widyawati@uq.net.au Funding information Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Scholarship digms. This systematic literature review explores three key research themes within the SRI literature, identifying a significant disconnect between themes and a fixation on the financial (as opposed to ethical) paradigm. One of the foundations of SRI is environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics. This review confirms the importance of ESG metrics in the SRI field, as they play two crucial roles, namely, as a proxy for sustainability performance and an enabler of the SRI market. However, there are two main issues related to ESG metrics that undermine their reliability: a lack of transparency and a lack of convergence. K E YW O RD S ESG, literature review, responsible investment, sustainability, sustainable development 1 | IN T R O DU C T ION literature is not well mapped, and there is little understanding of the importance of ESG metrics. Investors play a vital role in the global effort to achieve sustainable This review of SRI literature offers two main contributions. First, development goals by ensuring that capital is appropriately raised it provides a unique visual tool to analyze the literature in the form and allocated (Principles for Responsible Investment, 2017). The of a bibliographic map. The findings reveal continuously dispropor- practice of integrating sustainability criteria (particularly environmen- tionate academic attention on the financial paradigm of SRI, particu- tal, social, and governance [ESG] ratings) in investment analysis is larly the financial performance of SRI portfolios. This fixation is a known as responsible investing or socially responsible investment potential distraction from the ultimate goal of SRI, which is for a (SRI). SRI has gained increasing attention and popularity over the company to become more ethical and sustainable. The map also dem- recent years, and the value of SRI portfolios has grown significantly onstrates a significant disconnection between different SRI research (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, 2018). However, investors themes. have raised concerns regarding the lack of a clear definition of Second, this review identifies new insights into the importance of when investments can be classified as (socially) responsible, the ESG metrics. The majority of the SRI literature applies ESG metrics as absence of standards for SRI investments, and the quality of avail- a proxy for sustainability performance. In doing so, the literature con- able data on ESG ratings of companies (Avetisyan & Hockerts, tinues to exhibit a lack of transparency in addition to convergence 2017; Friede, 2019). issues, both of which undermine the quality and reliability of ESG Similarly, the literature reveals considerable diversity in the con- metrics. This review asserts that ESG metrics play a role as an ceptual understanding of SRI (Höchstädter & Scheck, 2015) albeit with enabler of the SRI market, with a range of potential future research a tendency to focus on financial concepts, particularly the financial avenues. performance of SRI portfolios (Capelle‐Blancard & Monjon, 2012). This paper proceeds as follows. Data collection is described in The ESG literature has also raised issues regarding the transparency Section 2, and bibliometric analysis using HistCite™ software is and reliability of existing metrics (Dorfleitner, Halbritter, & Nguyen, outlined in Section 3. This is followed by a discussion of the key 2015; Semenova & Hassel, 2015). However, the diversity of SRI themes in the SRI literature (Section 4) and recent research trends Bus Strat Env. 2020;29:619–637. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/bse © 2019 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment 619 620 WIDYAWATI (Section 5). Section 6 discusses ESG metrics in more detail. Section 7 3 | BIBLIOMETRIC ANALYSIS provides a discussion of the main findings and concludes the paper Bibliometric analysis of the collection reveals increasing interest in SRI with suggestions for future research. over time. Figure 1 shows a significant increase in SRI studies over the last decade, with the highest number of publications recorded in 2016. Ten journals (Table 2) are significant contributors to the field, with the majority being multidisciplinary business and business ethics publica- 2 | DATA tions. These journals published 200 articles (46% of the total articles). Studies analyzed in this review were retrieved from the Social Science The Journal of Business Ethics was the largest contributor with 112 arti- Citation Index (SSCI) by Thomson Reuter Web of Sciences (WoS). The cles. The Journal of Business Ethics is also the most cited, with a total search was performed on April 6, 2017, using a Boolean search with Local Citation Score (LCS) of 762. LCS is a score provided by the keywords “social* responsible mutual fund*” OR “social* responsible HistCite™ software that shows “the number of times a paper is cited fund*” OR “ethic* mutual fund*” OR “ethic* fund” OR “ethic* trust” by other papers in the local collections” (Garfield, 2009). Financial OR “ESG” OR “social* responsible invest*” OR “sustainab* invest*” Analysts Journal exhibits the most citations per paper, with 66.5 LCS OR “sustainab* financ*” OR “ethic* invest*” OR “responsible invest*.” per article. Table 3 shows the top 10 journals with the highest LCS The search included all English‐language articles indexed in the SSCI per paper; the majority of journals are finance related. from 1900 to 2016. The keywords were adapted from Eccles and The bibliometric analysis of influential SRI articles is used to pro- Viviers (2011) and Höchstädter and Scheck (2015) as the most fre- duce a bibliographic map using HistCite™. There is no exact rule about quently used terms for SRI. The wildcard character (*) was used to how to identify influential articles. However, the cut‐off is typically the obtain results that contain variations of the search keywords. For citation score where citations begin to level off. With a cut‐off point example, sustainab* will match both “sustainable” and “sustainability.” set at LCS ≥15, a total of 63 influential articles were identified. These The OR term was used to expand the search. articles represent more than 14% of the original 429 articles. Table 4 The search yielded a total of 634 articles. Information for each arti™ cle was downloaded and imported to the HistCite software for fur- presents citation data, including citation counts, of these influential articles. ther analysis. First, manual data cleaning was performed to ensure Figure 2 shows the bibliographic map with the 63 articles displayed ™ the relevance of articles. An article was removed from the HistCite as nodes (circles), with the size of the node representing each article's collection if it (a) was published in a nonpeer‐reviewed publication, LCS score. The arrows and lines between nodes represent citation (b) was published in nonbusiness academic journals, or (c) did not dis- connections. Clusters of closely connected nodes reveal the existence cuss any SRI topics. Articles that addressed SRI, but not as the main of several key research themes. discussion, were also excluded from the HistCite™ collection to main- Full‐text analysis is used to identify the research themes, involving tain the focus of the review. An example of such an article is Maynard manual comparison of articles to identify similarities and differences. (2008), which explores the impacts of climate change on insurers. This This approach is adapted from Ryan and Bernard (2003), who describe article mentions SRI as an option to help insurers manage climate different techniques for identifying themes in qualitative research. This change risk but does not offer more elaborate discussion. The manual review identifies three main research themes in the SRI literature data cleaning removed 230 articles from the collection. (represented by the shaded areas within the map). These themes are ™ Second, HistCite software (version 12.03.17) was used to conduct (a) investor behavior (IB), (b) SRI development (DEV), and (c) SRI perfor- bibliometric analysis and data visualization of articles retrieved from mance (PERF). These themes are explored in detail in the following Web of Science (including SSCI). The software facilitated the creation section. of a citation index that outlined the chronological network of citations among the set of documents (Garfield, Pudovkin, & Istomin, 2003). A cited reference search, to reveal all references cited by articles in the 4 | R E S E A R C H T H E M E S O F S R I LI T E R A T U R E collection, was carried out to ensure that all important SRI articles were captured and that none were inadvertently overlooked. The cited 4.1 | Investor behavior studies reference search identified the most relevant articles within the top 150 cited references. An additional 25 articles were found and manu- Studies into SRI investor behavior assess motivation, investment pat- ally added to HistCite™ (Table 1). tern, and decision making. This theme is founded on the assumption ™ The next step was to manually check all articles in the HistCite that SRI investors are different from conventional investors, as database to ensure that there were no duplications or inconsistencies. explored in 13 of the influential studies published in multidisciplinary To avoid subjective bias, two other researchers reviewed the manual journals. data cleaning and manual addition process and verified the results of Initial studies on this theme focus on understanding individual the process. In the case of disagreement, the articles were re‐ investors. An early study by Rosen, Sandler, and Shani (1991) argues evaluated until consensus was reached. The final collection used in this that understanding the characteristics of SRI investors, particularly review comprises 429 articles. demographics and motivation, is central to understanding their 621 WIDYAWATI TABLE 1 List of additional articles Author(s) Year Title LCS Reason for manual addition Statman, M. 2000 Socially responsible mutual funds 102 Not available in SSCI Hamilton, S.; Jo, H.; Statman, M. 1993 Doing well while doing good? The investment performance of socially responsible mutual funds 84 Not available in SSCI Sparkes, R.; Cowton, C. J. 2004 The maturing of socially responsible investment: A review of the developing link with corporate social responsibility 66 Not captured in the initial search Barnett, M. L.; Salomon, R. M. 2006 Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance 49 Not matching the keywords Briston, R. J.; Mallin, C. A.; Saadouni, B. 1995 The financial performance of ethical investment funds 48 Not available in SSCI Kreander, N.; Gray, R. H.; Power, D. M.; Sinclair, C. D. 2005 Evaluating the performance of ethical and non‐ethical funds: A matched pair analysis 46 Not captured in the initial search Gregory A.; Matatko J.; Luther R. 1997 Ethical unit trust financial performance: Small company effects and fund size effects 44 Not available in SSCI Bello, Z. Y. 2005 Socially responsible investing and portfolio diversification 44 Not available in SSCI Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. 2009 The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets 43 Not matching the keywords Sauer, D. A. 1997 The impact of social‐responsibility screens on investment performance: Evidence from the Domini 400 Social Index and Domini Equity Mutual Fund 43 Not available in SSCI Bollen, N. P. B. 2007 Mutual fund attributes and investor behavior 38 Not matching the keywords Luther R. G.; Matatko J.; Corner D. C. 1992 The investment performance of UK “ethical” unit trusts 37 Not available in SSCI Statman, M. 2006 Socially responsible indexes: Composition, performance, and tracking error 27 Not matching the keywords Goldreyer, E. F.; Diltz, J. D. 1999 The performance of socially responsible mutual funds: Incorporating sociopolitical information in portfolio selection 26 Not available in SSCI Sparkes, R. 2001 Ethical investment: Whose ethics, which investment? 24 Not available in SSCI Mackenzie, C.; Lewis, A. 1999 Morals and markets: The case of ethical investing 23 Not available in SSCI Gregory, A.; Whittaker, J. 2007 Performance and performance persistence of “ethical” unit trusts in the UK 21 Not matching the keywords Brammer, S.; Brooks, C.; Pavelin, S. 2006 Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures 19 Not matching the keywords Knoll, M. S. 2002 Ethical screening in modern financial markets: The conflicting claims underlying socially responsible investment 17 Not matching the keywords Irvine, W. B. 1987 The ethics of investing 16 Not matching the keywords Cowton, C. J. 1999 Playing by the rules: Ethical criteria at an ethical investment fund 15 Not available in SSCI Williams, G. 2007 Some determinants of the socially responsible investment decision: A cross‐country study 15 Not available in SSCI Beal, D.; Goyen, M.; Phillips, P. 2005 Why do we invest ethically? 15 Not matching the keywords (Continues) 622 TABLE 1 WIDYAWATI (Continued) Author(s) Year Title LCS Reason for manual addition Nilsson, J. 2009 Segmenting socially responsible mutual fund investor: The influence of financial return and social responsibility 15 Not matching the keywords Fowler, S. J.; Hope, C. 2007 A critical review of sustainable business indices and their impact 14 Not matching the keywords Note. Sorted by LCS. Abbreviations: LCS, Local Citation Score; SSCI, Social Science Citation Index. FIGURE 1 Total publication output of socially responsible investment studies per year TABLE 2 Top 10 publishing journals in the field of SRI No. Publication title Articles published (1987–1996) Articles published (1997–2006) Articles published (2007–2016) Total articles Total LCS 1 Journal of Business Ethics 2 31 79 112 762 2 Journal of Banking & Finance 1 15 16 290 3 Business Ethics ‐ A European Review 2 11 13 76 4 Corporate Governance ‐ An International Review 2 9 11 45 5 Sustainable Development 1 9 10 29 6 Journal of Cleaner Production 1 8 9 5 7 Business & Society 8 8 11 8 Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 1 5 7 213 9 European Journal of Operational Research 1 6 7 49 10 Business Strategy and The Environment 7 7 7 1 Total 200 Abbreviations: LCS, Local Citation Score; SRI, socially responsible investment. behavior. Similar studies in the United Kingdom (Lewis & Mackenzie, However, Williams (2007) indicates that the demographic 2000), Australia (McLachlan & Gardner, 2004), and Sweden (Nilsson, characteristics of SRI investors cannot fully explain their decision 2009) find that SRI investors have specific characteristics in terms of making; instead, investors' belief systems motivate SRI investment gender, education, and income. decisions. 623 WIDYAWATI TABLE 3 Top 10 publishing journals with highest LCS per article No. Publication title Total LCS Number of articles LCS per article 1 Financial Analysts Journal 266 4 66.50 2 Journal of Financial Research 44 1 44.00 3 Review of Financial Economics 43 1 43.00 4 Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 77 2 38.50 5 Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 213 7 30.43 6 Journal of Consumer Affairs 30 1 30.00 7 Managerial Finance 26 1 26.00 8 Strategic Management Journal 51 2 25.50 9 Journal of Financial Economics 76 3 25.33 10 Human Relations 45 2 22.50 Abbreviation: LCS, Local Citation Score. Studies regarding motivation suggest that both financial and nonfinancial motivations influence the SRI decision (Anand & Cowton, (largely review and conceptual articles), with the majority appearing in the Journal of Business Ethics. 1993; Beal, Goyen, & Phillips, 2005; Mackenzie & Lewis, 1999). How- The rapid development of SRI practices in the world's major econ- ever, the balance between the two motives varies among SRI investors omies during the early 2000s instigated studies on the growth and (Cullis, Lewis, & Winnett, 1992), which affects an investor's tolerance evolution of SRI. The practice of excluding certain stocks from invest- toward the risk of lower financial returns of SRI (Webley, Lewis, & ment portfolios based on nonfinancial criteria began in the United Mackenzie, 2001). States and United Kingdom before the 1990s. Some studies (Knoll, However, few studies have thoroughly investigated the belief sys- 2002; Schueth, 2003) indicate that SRI practices in these two coun- tems that underpin the behavior of SRI investors. Insight on how the tries have matured to a stage where SRI investment models are well belief systems of investors (be that religion, social values, or cultural developed. Despite this, there is still no consensus on whether SRI is norms) affect motivation to invest in SRI would enable more effective accepted as a mainstream practice in financial markets. Sparkes and and targeted promotion of SRI. Cowton (2004) argue that SRI adoption by influential and powerful It is likely that individual SRI investors are also institutional investors (such as pension funds), but it is unclear how institutional behavior mainstream investors affirms its mainstream status; however, market participants lack a unified perspective as to what constitutes SRI. relates to individual behavior regarding SRI. Studies on institutional SRI Although some commonality exists regarding definitions, the mech- investors have attempted to provide evidence on this. Cox, Brammer, anisms of SRI are very heterogeneous. What is considered to be SRI by and Millington (2004) find that institutional investors have similar one market participant might not be fully recognized by another investment patterns to individual investors, especially regarding the (Sandberg, Juravle, Hedesström, & Hamilton, 2008) Juravle and Lewis use of negative screening or exclusion strategies to balance financial (2008) identify impediments at individual and institutional levels, but and ESG goals. However, Cowton (1999) indicates that the values Renneboog, Ter Horst, and Zhang (2008b) suggest that SRI is likely and interests of the board of an ethical investment fund significantly to grow as investors become increasingly aware of ESG factors and influence the selection of ethical boundaries and criteria. more favorable regulatory frameworks emerge. Existing studies show that there is a potential tension between Studies into the heterogeneity of SRI mechanisms in local (Schueth, clients and management in terms of SRI implementation within an 2003) or international (Haigh & Hazelton, 2004; Sandberg et al., 2008; institutional investment, but more research is needed. Understanding Sparkes & Cowton, 2004) contexts generally agree that there are three the extent to which strategy development and the decision‐making main SRI mechanisms: screening, shareholder activism, and community process of SRI institutional investors is affected by SRI preferences investment. of individual investors is essential to understand the client–agent relationship. The screening strategy includes negative screening (the exclusion of certain investments based on ESG criteria) and positive screening (which relies on a “best‐in‐class” approach to selecting investments). Generally, investors are not involved in the operation of investee companies. In comparison, shareholder activism or shareholder advocacy 4.2 | SRI development studies relies on shareholders influencing companies to adopt more sustainable practices. Community investment requires significant involve- SRI development studies tend to focus on SRI in specific areas (e.g., ment, but investors who use this mechanism are typically interested countries), theoretical arguments for and against SRI, and participant in financing sustainability projects or sustainability related companies. roles in the SRI market. This theme comprises 16 influential studies Although academics broadly agree on the categorization of SRI 624 WIDYAWATI TABLE 4 No. List of highly cited papers in the collection HistCite ID Author(s) Title Publication Year LCS Theme 1 77 Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K.; Otten, R. International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style Journal of Banking & Finance 2005 105 SRI performance 2 27 Statman, M. Socially responsible mutual funds Financial Analysts Journal 2000 102 SRI performance 3 132 Renneboog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. D. Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior Journal of Banking & Finance 2008 86 SRI development 4 12 Hamilton, S.; Jo, H.; Statman, M. Doing well while doing good? The investment performance of socially responsible mutual funds Financial Analysts Journal 1993 84 SRI performance 5 59 Sparkes, R.; Cowton, C. J. The maturing of socially responsible investment: A review of the developing link with corporate social responsibility Journal of Business Ethics 2004 66 SRI development 6 71 Derwall, J.; Guenster, N.; Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K. The eco‐efficiency premium puzzle Financial Analysts Journal 2005 57 SRI performance 7 126 Renneboog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. The price of ethics and stakeholder governance: The performance of socially responsible mutual funds Journal of Corporate Finance 2008 55 SRI performance 8 91 Barnett, M. L.; Salomon, R. M. Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance Strategic Management Journal 2006 49 SRI performance 9 16 Briston, R. J.; Mallin, C. A.; Saadouni, B. The financial performance of ethical investment funds Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 1995 48 SRI performance 10 80 Kreander, N.; Gray, R. H.; Power, D. M.; Sinclair, C. D. Evaluating the performance of ethical and non‐ethical funds: A matched pair analysis Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 2005 46 SRI performance 11 18 Gregory A.; Matatko J.; Luther R. Ethical unit trust financial performance: Small company effects and fund size effects Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 1997 44 SRI performance 12 68 Bello, Z. Y. Socially responsible investing and portfolio diversification Journal of Financial Research 2005 44 SRI performance 13 19 Sauer, D. A. The impact of social‐ responsibility screens on investment performance: Evidence from the Domini 400 social index and Domini equity mutual fund Review of Financial Economics 1997 43 SRI performance 14 45 Schueth, S. Socially responsible investing in the United States Journal of Business Ethics 2003 43 SRI development 15 168 Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets Journal of Financial Economics 2009 43 SRI performance 16 109 Kempf, A.; Osthoff, P. 2005 report on socially responsible investing trends in the United States European Financial Management 2007 42 SRI performance 17 96 Bauer, R.; Derwall, J.; Otten, R. The ethical mutual fund performance debate: New evidence from Canada Journal of Business Ethics 2007 41 SRI performance 18 40 2001 39 SRI performance (Continues) 625 WIDYAWATI TABLE 4 No. (Continued) HistCite ID Author(s) Title Publication Year LCS Heinkel, R.; Kraus, A.; Zechner, J. The effect of green investment on corporate behavior Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis Bollen, N. P. B. Mutual fund attributes and investor behavior Theme Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 2007 38 SRI performance 19 107 20 9 Luther R. G.; Matatko J.; Corner D. C. The investment performance of UK “ethical” unit trusts Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal 1992 37 SRI performance 21 28 Lewis, A.; Mackenzie, C. Morals, money, ethical investing and economic psychology Human Relations 2000 31 SRI performance 22 144 Galema, R.; Plantinga, A.; Scholtens, B. The stocks at stake: Return and risk in socially responsible investment Journal of Banking & Finance 2008 31 Investor behavior 23 7 Rosen, B. N.; Sandler, D. M.; Shani, D. Social‐issues and socially responsible investment behaviour—A preliminary empirical‐investigation Journal of Consumer Affairs 1991 30 Investor behavior 24 30 Cummings, L. S. The financial performance of ethical investment trusts: An Australian perspective Journal of Business Ethics 2000 27 SRI performance 25 85 Statman, M. Socially responsible indexes— Composition, performance, and tracking error. Journal of Portfolio Management 2006 27 SRI performance 26 26 Goldreyer, E. F.; Diltz, J. D. The performance of socially responsible mutual funds: Incorporating sociopolitical information in portfolio selection Managerial Finance 1999 26 SRI performance 27 60 Haigh, M.; Hazelton, J. Financial markets: A tool for social responsibility? Journal of Business Ethics 2004 25 SRI development 28 36 Sparkes, R. Ethical investment: Whose ethics, which investment? Business Ethics‐A European Review 2001 24 SRI development 29 98 Schroder, M. Is there a difference? The performance characteristics of SRI equity indices Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 2007 24 SRI performance 30 133 Benson, K.; Humphrey, J. E. Socially responsible investment funds: Investor reaction to current and past returns Journal of Banking & Finance 2008 24 SRI performance 31 165 Sandberg, J.; Juravle, C.; Hedesstrom, T. M.; Hamilton, I. The heterogeneity of socially responsible investment Journal of Business Ethics 2009 24 SRI development 32 224 Edmans, A. Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices Journal of Financial Economics 2011 24 SRI performance 33 24 Mackenzie, C.; Lewis, A. Morals and markets: The case of ethical investing Business Ethics Quarterly 1999 23 SRI development 34 37 Webley, P.; Lewis, A.; Mackenzie, C. Commitment among ethical investors: An experimental approach Journal of Economic Psychology 2001 23 SRI development 35 53 Hallerbach, W.; Ning, H.; Soppe, A.; Spronk, J. A framework for managing a portfolio of socially responsible investments European Journal of Operational Research 2004 23 SRI performance 36 57 Mclachlan, J.; Gardner, J. A comparison of socially responsible and conventional investors Journal of Business Ethics 2004 23 SRI performance (Continues) 626 WIDYAWATI TABLE 4 No. (Continued) HistCite ID Author(s) Title Publication Year LCS Theme 37 63 Guay, T.; Doh, J. P.; Sinclair, G. Non‐governmental organizations, shareholder activism, and socially responsible investments: Ethical, strategic, and governance implications Journal of Business Ethics 2004 23 Investor behavior 38 86 Benson, K.; Brailsford, T. J.; Humphrey, J. E. Do socially responsible fund managers really invest differently? Journal of Business Ethics 2006 23 Investor behavior 39 163 Statman, M.; Glushkov, D. The wages of social responsibility Financial Analysts Journal 2009 23 Investor behavior 40 29 Lewis, A.; Mackenzie, C. Support for investor activism among UK ethical investors Journal of Business Ethics 2000 22 SRI development 41 56 Michelson, G.; Wailes, N.; Van Der Laan, S.; Frost, G. Ethical investment processes and outcomes Journal of Business Ethics 2004 22 SRI performance 42 167 Cortez, M. C.; Silva, F.; Areal, N. The performance of European socially responsible funds Journal of Business Ethics 2009 22 Investor behavior 43 46 Schwartz, M. S. The ethics of “ethical investing” Journal of Business Ethics 2003 21 SRI development 44 106 Gregory, A.; Whittaker, J. Performance and performance persistence of “ethical” unit trusts in the UK Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 2007 21 SRI performance 45 221 Derwall, J.; Koedijk, K.; Ter Horst, J. A tale of values‐driven and profit‐ seeking social investors Journal of Banking & Finance 2011 21 SRI performance 46 14 Anand, P.; Cowton, C. J. The ethical investor—Exploring dimensions of investment behavior Journal of Economic Psychology 1993 20 Investor behavior 47 58 Cox, P.; Brammer, S.; Millington, A. An empirical examination of institutional investor preferences for corporate social performance Journal of Business Ethics 2004 19 Investor behavior 48 90 Brammer, S.; Brooks, C.; Pavelin, S. Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures Financial Management 2006 19 SRI performance 49 228 Renneboog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. D. Is ethical money financially smart? Nonfinancial attributes and money flows of socially responsible investment funds Journal of Financial Intermediation 2011 19 SRI performance 50 127 Juravle, C.; Lewis, A. Identifying impediments to SRI in Europe: A review of the practitioner and academic literature Business Ethics‐A European Review 2008 18 SRI development 51 192 Lee, D.; Humphrey, J. E.; Benson, K.; Ahn, J. Y. K. Socially responsible investment fund performance: The impact of screening intensity Accounting and Finance 2010 18 SRI performance 52 42 Knoll, M. S. Ethical screening in modern financial markets: The conflicting claims underlying socially responsible investment Business Lawyer 2002 17 SRI development 53 50 Rivoli, P. Making a difference or making a statement? Finance research and socially responsible investment Business Ethics Quarterly 2003 17 SRI development 54 5 Irvine, W. B. The ethics of investing Journal of Business Ethics 1987 16 SRI development (Continues) 627 WIDYAWATI TABLE 4 No. (Continued) HistCite ID Author(s) Title Publication Year LCS Theme Sethi, S. P. Investing in socially responsible companies is a must for public pension funds—Because there is no better alternative Journal of Business Ethics 2005 16 SRI development 55 70 56 153 Derwall, J.; Koedijk, K. Socially responsible fixed‐income funds Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 2009 16 SRI performance 57 11 Cullis, J. G.; Lewis, A.; Winnett, A. Paying to be good—UK ethical investments Kyklos 1992 15 Investor behavior 58 25 Cowton, C. J. Playing by the rules: Ethical criteria at an ethical investment fund Business Ethics‐A European Review 1999 15 Investor behavior 59 69 Beal, D.; Goyen, M.; Phillips, P. Why do we invest ethically? Journal of Investing 2005 15 Investor behavior 60 89 Scholtens, B. Finance as a driver of corporate social responsibility Journal of Business Ethics 2006 15 Investor behavior 61 94 Williams, G. Some determinants of the socially responsible investment decision: A cross‐country study Journal of Behavioral Finance 2007 15 SRI development 62 147 Nilsson, J. Segmenting socially responsible mutual fund investor: The influence of financial return and social responsibility International Journal of Bank Marketing 2009 15 Investor behavior 63 161 Chatterji, A. K.; Levine, D. I.; Toffel, M. W. How well do social ratings actually measure corporate social responsibility? Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 2009 15 ESG measurement Note. Sorted by LCS. Abbreviations: LCS, Local Citation Score; SRI, socially responsible investment. mechanisms, there is no consensus on how or whether these mecha- critical role not only as an investor but also as an SRI advocate, nisms impact corporate practices. because their actions could encourage other investors, including credit Meanwhile, there are two main arguments concerning SRI's sus- investors (e.g., banks, private equity, and project financing providers; tainability impact. Rivoli (2003) applies financial market theory and Scholtens, 2006). Nongovernmental organizations also have important concludes that SRI portfolios that apply a screening strategy have a roles as investors and advocates by engaging in shareholder activism, better chance of achieving impact, provided that unrealistic assump- creating SRI funds, campaigning for SRI, or consulting with SRI funds tions regarding the SRI financial model (such as the perfect market (Guay, Doh, & Sinclair, 2004). These studies indicate the unique fea- assumption) are relaxed. Rivoli's argument is rooted in the belief that ture of the SRI market in which each participant can have more than financial markets influence the company's policy and behavior (Irvine, one role. Considering the interconnectedness among market partici- 1987). In contrast, Sparkes and Cowton (2004) argue that shareholder pants, the field is likely to benefit from further study into the relation- activism is likely to be the most potent method for influencing corpo- ship dynamics between different participants in different SRI markets. rate policies. This would help identify the optimum mechanism for coordination and Despite a lack of empirical evidence (Renneboog et al., 2008b), it is collaboration. generally agreed (theoretically at least) that SRI is capable of affecting corporate behavior. It is also crucial that SRI fund managers are trans- 4.3 | SRI performance studies parent about their products so that investors are informed about the expected impacts of their investments (Michelson, Wailes, Van Der SRI performance is the most dominant research theme in the SRI liter- Laan, & Frost, 2004). ature, with 34 studies examining the financial impact of SRI practices It can be concluded that, conceptually, SRI facilitates sustainable (including mutual funds, trusts, and portfolios). The majority of studies development, even if there is disagreement about how to achieve in this stream are published by mainstream financial journals, represen- significant impact. However, empirical studies are needed to provide tative of the growing acceptance of SRI as an important topic in evidence to resolve the current debate on this topic. finance research. Every SRI market participant plays an important role. Sethi (2005) The assumed trade‐off between return and responsibility, due to argues that institutional investors of pension funds play a potentially restriction of the pool of assets that can be included in the investment 628 FIGURE 2 com] WIDYAWATI Bibliographic map of influential articles in the socially responsible investment field [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary. portfolio, is a major concern for SRI. However, it is theoretically possi- Some studies demonstrate that integrating sustainability criteria ble for investors to create SRI portfolios that fulfill their required has no significant impact on portfolio return, meaning that the return return criteria. One method is the multiattribute portfolio approach of SRI portfolios is not statistically different from returns of conven- with predetermined restrictions (Hallerbach, Ning, Soppe, & Spronk, tional portfolios. This result is consistent for trusts (Cummings, 2004). Empirical studies into SRI performance investigate the return 2000), mutual funds (Bauer, Derwall, & Otten, 2007; Bauer, Koedijk, of such portfolios with mixed findings. & Otten, 2005; Cortez, Silva, & Areal, 2009; Derwall & Koedijk, 629 WIDYAWATI 2009), stock indices (Schröder, 2007; Statman, 2006), and hypothetical result is more common in one setting. Table 5 shows examples of dif- portfolios (Sauer, 1997). A probable explanation is that SRI portfolios, ferent results for studies conducted in similar contexts, which reflect especially mutual funds, are generally managed similarly to conven- both a convergence and a divergence of SRI performance studies. tional funds (Benson, Brailsford, & Humphrey, 2006). Namely, the studies tend to converge on the mutual fund setting but Alternatively, some studies present evidence that indicates that SRI produce divergent results even in the same setting. This fragmentation does have a positive effect on returns by comparing equity portfolios that exists within the SRI performance literature provides opportuni- with high and low ESG scores. These studies show that a positive ties for future research. screening strategy is generally advantageous for investors (Statman & Glushkov, 2009) as it provides a positive abnormal return, even after taking into account additional transaction costs for SRI portfolios 5 | RECENT RESEARCH TRENDS (Kempf & Osthoff, 2007). Similar positive results are presented by studies that investigate the return of portfolios created on specific In addition to bibliometric mapping, a second content analysis was ESG criteria such as eco‐efficiency (Derwall, Guenster, Bauer, & performed on more recent articles to counter the inherent shortcom- Koedijk, 2005) and employee satisfaction (Edmans, 2011). These stud- ing whereby mapping tends to discredit newly published articles ies show that SRI investors who remain loyal and hold SRI portfolios without many citations. The bibliographic map demonstrates that over the long term are likely to be rewarded with incremental returns. the most influential articles were published between 1991 and Further, SRI portfolios including SRI mutual funds are generally less 2011; however, Figure 1 shows that published SRI studies peaked volatile (Bollen, 2007). from 2014 to 2016. Additional content analysis reveals continued In contrast, empirical studies find evidence that portfolios based on development in the three key research themes described in the pre- ESG criteria have a negative effect on financial returns. They reveal vious section. Although studies on SRI performance continue to that returns for companies with a high ESG score are lower than mar- dominate, several significant emerging trends are also evident in ket return (Brammer, Brooks, & Pavelin, 2006) and ESG‐based stock each research theme. selection lowers the stock's book‐to‐market ratio (Galema, Plantinga, SRI studies on investor behavior continue to focus on individual & Scholtens, 2008). Studies in 18 countries on SRI mutual funds and institutional investors. Noticeable trends include increasing atten- also reach similar conclusions (Gregory, Matatko, & Luther, 1997; tion on individual values and beliefs as drivers of SRI investor behavior Renneboog, Ter Horst, & Zhang, 2008a). The negative impact can be (Bauer & Smeets, 2015; Diouf, Hebb, & Touré, 2016; Dumas & exacerbated by screening intensity (Lee, Humphrey, Benson, & Ahn, Louche, 2016; Durand, Koh, & Tan, 2013; Glac, 2012; Sandbu, 2010). Although empirical evidence on this negative impact supports 2012). Studies on the return sensitivity of SRI investors reveal that the theory of a trade‐off between social responsibility and financial they are less concerned about negative performance (Martí‐Ballester, return, this does not mean that investors should avoid investing in 2015; Peifer, 2014), even if they expect a certain level of financial SRI; however, they must be aware of the trade‐off and potentially return (Paetzold & Busch, 2014; Pérez‐Gladish, Benson, & Faff, lower returns. 2012), and different groups of investors expect different returns (Berry Mutual funds managers also need to consider funds flow as it rep- & Junkus, 2013). resents investors' sentiment and future cash flow of the funds. In this Researchers have also begun to pay more attention to the motiva- regard, SRI funds are found to be less sensitive to past returns than tions of institutional investors. External drivers, such as regulatory conventional funds (Benson & Humphrey, 2008; Renneboog, Ter environment (Sievänen, Rita, & Scholtens, 2013), and internal drivers, Horst, & Zhang, 2011). In other words, investors are unlikely to such as product development and risk management (Crifo, Forget, & withdraw their investments from SRI funds because of past negative Teyssier, 2015), have been the subject of investigation. However, returns. researchers still have not fully explored in‐depth cross‐analysis of the Meanwhile, some studies identify a mixed effect of SRI. The mul- behavior of individual and institutional SRI investors. tidimensional and contextual nature of SRI means that SRI portfolios Recent studies present important insights into two issues regarding can perform differently in different contexts. Derwall, Koedijk, and SRI development: SRI mainstreaming and the heterogeneity of SRI Ter Horst (2011) and Barnett and Salomon (2006) present evidence mechanisms. Viviers and Eccles (2012) argue that SRI practices are that different screening mechanisms may affect financial perfor- increasingly concentrated on screening (both positive and negative) mance. Negative screening might lead to a low ESG scored firm and shareholder activism. SRI institutional investors are becoming being undervalued due to lack of demand. Positive screening might more interested in shareholder activism, even though there is incon- mean the real value from ESG is not yet recognized for high scored clusive empirical support for the approach. Kolstad (2016) suggests firms, resulting in their stock being undervalued; returns could be that this may be due to shareholder activism triggered by political earned as the stocks move toward their true values. Therefore, argu- and bureaucratic motives to appease stakeholder pressure, rather than ments both for and against SRI can be justified depending on the by effectiveness and efficiency motives. context. Recent research presents two conceptual differences regarding This review finds no indication that specific characteristics of influ- the effect of the heterogeneity of SRI mechanisms on the SRI ential SRI performance studies influence the results. That said, one mainstreaming effort, namely, that it facilitates or impedes the process. 630 WIDYAWATI TABLE 5 Examples of different results for SRI performance studies in similar contexts Context No. significant difference SRI positive impact SRI negative impact Multi‐ impacts Study object Mutual funds Trust Equity portfolio Individual firm stocks 13 1 1 0 1 2 4 0 2 1 1 2 2 0 0 0 Approach Comparing SRI portfolio versus conventional benchmark Comparing high ESG versus low ESG scored portfolio 17 3 3 2 0 4 3 0 CAPMa CAPMa and multifactor model Multifactor model Regression 10 1 3 2 2 2 3 0 0 2 3 0 1 0 1 0 Main quantitative model used Abbreviations: CAPM, capital asset pricing model; SRI, socially responsible investment. a Including Sharpe's ratio and Jensen's alpha. The facilitation argument suggests that heterogeneity makes SRI more Plà‐Santamaria (2012) show that a portfolio with a “green” reputation appealing to a broad range of investors who have different interests can earn lower returns than traditional portfolios. and concerns (Child, 2015; Crifo & Mottis, 2016). The impediment Second, SRI performance in emerging economies has gained argument suggests that the idiosyncrasies of SRI undermine collective increasing attention. In their Brazilian study, Ortas, Moneva, and beliefs, leading to confusion and reluctance to implement SRI (Dumas Salvador (2012) indicate that SRI performs as well as the market in & Louche, 2016). Despite these differences in opinion, the consensus bullish periods. Cunha and Samanez (2013) find that it suffers from is that more effort is required to bring SRI to the forefront of main- losses in periods of crisis due to constraints that lead to higher risks. stream financial markets. South African SRI research reveals no significant impact of ESG on Recent studies present more evidence on the importance of the context of SRI and insights into the unresolved debate on SRI's impact financial performance (Chipeta & Gladysek, 2012; Demetriades & Auret, 2014). on financial performance. Different SRI settings, such as screening Third, recent papers have contributed to understanding SRI perfor- mechanisms and screening intensity, can have different impacts on mance in a specific market situation. These include studies on market the financial performance of SRI portfolios. For example, Capelle‐ disturbance due to an increase in competition (In, Kim, Park, Kim, & Blancard and Monjon (2014) find that negative screening leads to Kim, 2014) and studies pertaining to SRI during the global financial cri- underperformance, whereas positive screening has no impact on the sis (Nofsinger & Varma, 2014). financial performance of French SRI funds. In contrast, Auer (2016) Some recent studies adopt the unique approach of analyzing the argues that negative screening has no impact, whereas positive performance of sin portfolios as the antithesis of SRI portfolios. Sin screening negatively impacts the financial performance of European stocks are perceived to be morally or socially unacceptable, such as stock portfolios. tobacco, alcohol, weapons, and gambling companies. Recent studies New narratives about methodological concerns of SRI performance present empirical evidence that a portfolio of only sin stocks performs studies have emerged, including Rathner's (2013) systematic meta‐ better than the market (Soler‐Domínguez & Matallín‐Sáez, 2016); analysis of 25 SRI performance studies. Rathner (2013) reveals that however, merely including sin stocks in a regular portfolio does not results are affected by characteristics such as survivorship bias, focus affect returns (Borgers, Derwall, Koedijk, & ter Horst, 2015; Lobe & on the U.S. market, and the study period. As a result, SRI performance Walkshäusl, 2016). Therefore, excluding sin stocks from a portfolio is studies should be interpreted with caution. Stellner, Klein, and Zwergel expected to have no impact on returns. (2015) note that bias could be reduced if mediating or moderating variables, such as country‐specific variables, are integrated. Other recent studies concentrate on specific SRI issues in several 6 | DISCUSSION OF ESG METRICS ways. First, more attention has been given to the impact of a particular dimension of ESG. For instance, Borgers, Derwall, Koedijk, and ter In the collection, 28 studies examine ESG measurement, and 238 Horst (2013) provide evidence that stakeholder engagement is posi- papers incorporate ESG metrics. Further analysis reveals that the roles tively associated with long‐term, risk‐adjusted returns. Girerd‐Potin, of ESG metrics are highly related to the type of study. True to the Jimenez‐Garcès, and Louvet (2014) extend this result for all types nature of ESG metrics as a measurement unit, quantitative empirical of stakeholders. Ballestero, Bravo, Pérez‐Gladish, Arenas‐Parra, and studies mainly apply ESG metrics as a proxy for sustainability 631 WIDYAWATI performance. Meanwhile, qualitative empirical studies and conceptual scoring model that distinguishes performance ranges. The result is a studies suggest that ESG metrics play a more fundamental role as an rating or ranking form of ESG metrics. enabling factor of the SRI market. SRI performance studies have applied both first and second gener- Analysis also facilitates the identification of ESG metrics providers. ation ESG metrics as a proxy for sustainability performance, both KLD is arguably the oldest ESG rating agency and the most popular directly and indirectly. The direct application involves the use of source of ESG metrics; KLD scoring is used in 16 SRI performance “raw” ESG metrics, namely, the aggregated ESG score or scores for studies. More recently, studies have also applied data from other U. each ESG dimension. The indirect application involves the use of S.‐ and European‐based rating agencies such as ASSET4 (Stellner ESG metrics that have been further processed to form an SRI index et al., 2015), Bloomberg (Nollet, Filis, & Mitrokostas, 2016), or used in an investment analysis that results in SRI mutual funds. Sustainalytics (Auer, 2016), EIRIS (Brammer et al., 2006; Wu & Shen, Direct application of ESG metrics has reduced some biases 2013), SAM (Bird, Momenté, & Reggiani, 2012; Xiao, Faff, Gharghori, because it eliminates the effect of transaction costs and managerial & Lee, 2013), Vigeo (Girerd‐Potin et al., 2014), and Innovest issues (i.e., investment manager skills or preferences) by creating (Brzeszczyński & McIntosh, 2014; Derwall et al., 2005). There is little unique (hypothetical) portfolios. However, direct application means discourse on ESG metrics provided by local or regional agencies. This that measurement issues related to ESG metrics might directly affect section discusses the use of ESG metrics as a proxy for sustainability study results. Nevertheless, the increasing popularity of this approach performance (Section 6.1) and an enabling factor for the SRI market within recently published SRI performance studies indicates that (Section 6.2). researchers recognize and value its benefits. There are eight influential studies (e.g., Brammer et al., 2006; Kempf & Osthoff, 2007; Sauer, 1997) and 47 recent articles (e.g., Auer, 2016; Girerd‐Potin et al., 6.1 | ESG metrics as a proxy for sustainability performance 2014; Xiao et al., 2013) that directly apply ESG metrics as a proxy for sustainability performance. Researchers have also extensively applied indirect ESG metrics, Operationalization of sustainability performance is challenging due to with many analyzing data on SRI mutual funds. Of the SRI performance the broad and contextual definition of sustainability. The literature studies, 44 examine the performance of SRI mutual funds, including 12 indicates that such operationalization has developed in line with the influential studies and 32 recent studies. A major concern is that only evolution of SRI practices. Early SRI in the 1990s generally applied some of the studies (e.g., Borgers et al., 2015; Capelle‐Blancard & negative screening by excluding nonethical or nonsocially responsible Monjon, 2014; Henke, 2016) provide information about the raw ESG companies (Haigh & Hazelton, 2004; Schueth, 2003; Sparkes & metrics used to create the funds. This may simply reflect the extensive Cowton, 2004). In this case, ESG metrics are mainly applied to filter effort needed to identify the raw ESG metrics, especially if the studies out nonethical companies. As a result, most first‐generation ESG met- examine a vast number of mutual funds. Moreover, not all mutual rics, such as the original KLD rating, consist of binary codes to indicate funds provide this information. This lack of transparency and the issues compliance or noncompliance with selected sustainability criteria (Hart of transaction costs and managerial influence are shortcomings of & Sharfman, 2015; Sharfman, 1996). However, the criteria are debat- mutual funds data. Regardless, studies of SRI mutual funds present a able because there is no consensus on the definition of social respon- realistic view of SRI, because mutual funds are arguably one of the sibility (Michelson et al., 2004). This type of ESG metric is highly most popular investment vehicles for SRI investors. It is also relatively subjective and inconsistent, especially when there is a lack of disclo- easy to identify SRI mutual funds via fund registers compiled by SRI sure regarding the methodology. forums, such as the U.S. SIF (Benson et al., 2006; Benson & Humphrey, The next stage of evolution of ESG metrics is linked to the increasing 2008; Renneboog et al., 2011) and Eurosif (Cortez et al., 2009). popularity of positive screening or “best‐in‐class” practices. As an exclu- The type of ESG metrics used as a proxy of sustainability measure- sionary SRI strategy, negative screening is often regarded as a punish- ment is related to the scope and model employed by these studies. A ment for nonethical companies (Heinkel, Kraus, & Zechner, 2001). total of 15 SRI performance studies use ESG or SRI indices in their However, for some investors, negative screening no longer reflects analysis. These studies generally implement a comparison model, the sustainability values they wish to achieve (de Colle & York, 2009). namely, comparing the performance of SRI portfolios with either con- Furthermore, SRI practices have recently shifted toward a balance ventional portfolios or market benchmarks (Kappou & Oikonomou, between punishing non‐performing companies and rewarding best 2016; Schröder, 2007; Statman, 2006). The most commonly used SRI performing companies (Haigh & Hazelton, 2004; Heinkel et al., 2001). indices are Domini400 (based on KLD data), FTSE4Good (data from Using binary‐based ESG metrics is a challenge when evaluating and EIRIS), and Dow Jones Sustainability Index (data from SAM) and pub- selecting best performing companies. Therefore, ESG metrics have lished in either the United States or United Kingdom. Other domestic evolved to more accurately reflect sustainability performance to facil- stock indices tend to be used in studies that specifically examine SRI itate a change in SRI practices (Renneboog et al., 2008b). In this sec- performance in a specific country (Chipeta & Gladysek, 2012; Ortas ond generation of ESG metrics, an aggregated score is provided, et al., 2012; Ortas, Moneva, Burritt, & Tingey‐Holyoak, 2014). more specific criteria for each dimension developed, weights of Despite the evolution of ESG metrics and their popularity as a each dimension reassessed, and the binary code expanded, yielding a proxy for sustainability performance, the metrics remain flawed. The 632 WIDYAWATI lack of transparency continues to be a key issue (Busch, Bauer, & one of the main factors enabling the growth of the U.K. SRI market. Orlitzky, 2016; Delmas & Blass, 2010). Even though several ESG rating Similarly, the French SRI market grew substantially after an ESG rating agencies have published more information regarding their methodol- agency (Arese, subsequently known as Vigeo) was launched in 1997 ogy, much information crucial for meaningful interpretation and accu- (Arjaliès, 2014; Gond & Boxenbaum, 2013). This acceleration is ampli- rate comparison has not been fully disclosed. Changes in the ESG fied when the establishment is accompanied by compatible regulation information market as new agencies are launched and established data and adoption of the metrics by influential market players (Kreander, providers enter the market exacerbates transparency concerns and McPhail, & Beattie, 2015; Vasudeva, 2013). However, this acceleration creates additional confusion (Delmas, Etzion, & Nairn‐Birch, 2013). effect can be dampened by lack of transparency and standardization in Moreover, there is still no standard for ESG metrics, which means that the use of ESG metrics by SRI analysts (Juravle and Lewis, 2008). data are fragmented and inconsistent due to differences in data collec- ESG metrics are also a useful tool to educate and build awareness tion, incompatible data formats, and different levels of quality control about SRI. Studies indicate that investors with limited awareness and (Sethi, 2005, Juravle & Lewis, 2008). Although the different metrics understanding of available ESG metrics are hesitant to invest in SRI consist of some common dimensions, the aggregate measurement (Escrig‐Olmedo, does not converge (Semenova & Hassel, 2015). Recent studies have Giamporcaro & Pretorius, 2012). For SRI investors, there is concern also uncovered other measurement issues including bias toward larger about whether their ethical beliefs can be integrated into investment companies (Jun, 2016) and a lack of predictive power (Chatterji, analysis. ESG metrics help investors understand the integration pro- Levine, & Toffel, 2009). Current practices in ESG measurement need cess by showing the various options, in terms of ESG dimensions to improve significantly if ESG metrics are to be reliable and valid and measurements, that they can choose in order to translate their (Busch et al., 2016). beliefs into investment criteria (Heinkel et al., 2001). It is thus likely Some alternative frameworks to help resolve the issues surrounding ESG metrics have been put forward (e.g., Cabello, Ruiz, Pérez‐ Muñoz‐Torres, & Fernández‐Izquierdo, 2013; that a lack of awareness about ESG metrics impedes SRI market growth. Gladish, & Méndez‐Rodríguez, 2014; Kocmanova & Simberova, 2012; Kocmanová & Šimberová, 2014). However, the uptake and impact of these alternatives remain to be seen. The shortcomings of 7 | DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ESG metrics mean that information might not accurately represent a company's ESG performance, which in turn might mislead investors SRI is an important vehicle for capital allocation in the effort to achieve (Cheng et al., 2015). Consequently, investment analysts and academics sustainable development goals (PRI, 2017). Investors recognize that should exercise caution when using ESG metrics. ESG is crucial for the practice of SRI (Avetisyan & Hockerts, 2017; Friede, 2019). However, there is a lack of understanding of the impor- 6.2 | ESG metrics as an enabling factor for the SRI market tance of ESG metrics in the SRI literature. This review demonstrates that SRI is conceptualized differently across two main paradigms: It is a financial innovation born from ethical concerns about corporate ESG metrics also serve as an enabling factor for the SRI market. behavior. In other words, there are two sides to the SRI coin: ethical Studies on SRI investor behavior, SRI development, and ESG metrics and financial. suggest that ESG metrics provide legitimacy, accelerate growth, and The ethical paradigm views SRI as an instrument to pressure com- build awareness for the SRI market. ESG metrics are an essential ele- panies to change their policies and operate more ethically and sustain- ment in establishing an SRI market. ably. SRI advocates generally consider this to be SRI's ultimate goal. An ESG metric is a tool to adapt and align the cognitive frameworks A vital feature of this paradigm is the complex and multidisciplinary of SRI stakeholders with the professional standards of the financial context of SRI, which arises from the nature of ethics and sustainabil- sector. ESG metrics render SRI understandable and scalable to the ity. Investor behavior and SRI development themes mainly represent broader financial community and help ensure the legitimacy of SRI as this paradigm. A critical discussion in this paradigm concerns the best an emerging financial market (Déjean, Gond, & Leca, 2004). As SRI and most effective ways to achieve desired outcomes, considering markets develop, legitimacy is maintained by ESG rating agencies col- the vast heterogeneity of SRI mechanisms and the unique relationship laboratively and politically engaging with other macro actors in the among SRI market participants. financial market (Giamporcaro & Gond, 2016). It is thus important to The financial paradigm views SRI as new financial services offered have insights into the role of ESG metrics in establishing SRI markets to specific groups of investors and consequently assumes that SRI to promote new markets, especially in emerging economies. retains characteristics of traditional financial products. This assump- The introduction of ESG metrics is also vital to accelerate the tion is inherent in studies that emphasize the financial characteristics growth of emerging SRI markets. Reviews of SRI market development of SRI, such as returns, risks, and quantitative financial models. This in different countries reveal that SRI portfolios have grown signifi- paradigm is illustrated by extensive empirical studies on SRI perfor- cantly after ESG metrics were introduced or ESG rating agencies were mance. These studies have not yet come to a general consensus, and established. For instance, Cullis et al. (1992) and Solomon, Solomon, further analysis reveals that they tend to be conducted in similar, if and Suto (2004) credit the 1983 establishment of the U.K.'s EIRIS as not the same, contexts. For example, studies often use similar types 633 WIDYAWATI and sources of data (e.g., mutual funds data from U.S. SIF or Eurosif), and lack of consistency or convergence. A lack of transparency arises similar methodologies (e.g., multifactor model), and focus on certain because ESG data providers and rating agencies do not disclose suffi- countries or regions (e.g., United States, United Kingdom, and Europe). cient information about the processes and methodologies they use to Nevertheless, there is little empirical knowledge about the most effec- produce the metrics or the quality of the data used in the process. tive way to apply SRI as a quantitative financial model and how this Future research on this issue could examine rating agency disclosures, application affects market equilibrium. evaluate the level of transparency of different agencies, and subse- This review identifies three key research themes and contributes two related findings. First, SRI literature is dominated by studies of quently investigate the impact of the lack of transparency on companies and investors. SRI performance. This review indicates that far more SRI performance Regarding the lack of consistency or convergence, studies reveal studies have been published compared with other themes, in terms of that different rating agencies may score the same company differently both influential and recently published articles. The dominance of SRI because of differences in data collection and methodologies. However, performance studies is concerning because it suggests that academic the lack of transparency means that there is not enough information to discussion might be excessively fixated on output—that is, financial thoroughly compare the substance and calculation processes of ESG performance—and thus overlook SRI's ultimate goal, which is to metrics from different rating agencies. Studies on this lack of conver- change corporate behavior. One of the possible reasons for the gence generally analyze aggregated ESG metrics, demonstrating that dominance of SRI performance studies is the availability of data composite ESG scores and specific environmental scores published (Capelle‐Blancard & Monjon, 2012). Nevertheless, the heterogeneity by several major rating agencies (KLD, Trucost, Asset4, and GES) do of SRI practices is still not fully explored by SRI performance studies. not converge. More studies are required to investigate whether this For example, little work has been done on the financial impact of lack of convergence exists in other settings. Future studies could also shareholder activism. Another possible reason for the dominance of investigate whether there is a lack of convergence in the social and SRI performance studies is that academics are under increasing pres- governance dimensions of ESG. Studies on different or larger sample sure from financial markets to provide evidence on the financial impact sets would also improve understanding of convergence issues. Future of SRI practices. Studies on SRI development identify this as a short‐ studies could also capture the vast diversity of ESG metrics available term paradigm problem; that is, a mismatch between the relatively by including metrics from the relatively less studied rating agencies short‐term views of financial markets and the supposedly long‐term such as EIRIS, Vigeo, SAM, Innovest, and Sustainalytics. In addition, view of ESG. ESG is viewed as a long‐term issue because changes in more research on improving transparency and convergence while a company's behavior take longer to manifest than changes in the per- protecting the intellectual propriety of rating agencies are needed. formance of its stocks. The last finding regards the lack of understanding about the role of Second, the dominance of SRI performance studies is exacerbated ESG metrics as an enabling factor of SRI. The emergence of ESG met- by the lack of integration between different research themes. SRI rics is credited as one of the main factors that provide legitimacy for studies tend to refer to other studies within the same research theme. SRI markets, especially in their early stages of development. Subse- This tendency is illustrated in the bibliographic map, which shows very quently, as SRI markets develop, the establishment of ESG metrics is few connections between studies in different research themes. One often followed by accelerated growth in the number of transactions possible reason for this is that the two different paradigms stem from and investors. However, there is a lack of understanding about why different fields and thus have different conversation circles including and how this happens. Such an understanding is vital if a similar effect different publication avenues. A researcher from one field might not is to be achieved in emerging SRI markets in Asia and Africa. There is be aware of the studies performed in another. Therefore, it is impor- little research on this issue and what exists has been conducted in a tant to have more avenues for researchers from different fields to narrow context, such as a single country. Future studies that examine meet and discuss their research to build holistic awareness and under- how ESG metrics affect the dynamics of SRI markets are needed, as standing of SRI. are those that examine market players' perceptions. Insights into Future studies on SRI should also attempt to connect the different how the behavior and perception of investors and companies might paradigms of SRI. Such studies should explore more questions about change as a result of the emergence or modification of ESG metrics the conceptual, theoretical, and behavioral issues of SRI, which are would also be worth exploring. more related to SRI's ultimate goal. Possible topics for future studies The findings of this review contribute to the literature by present- include the relationship between financial performance of SRI portfo- ing a novel visualization tool to analyze the development of SRI lios and changes in ESG practices of companies included in the portfo- literature. This paper extends the findings of previous work by lio, the assessment of SRI financial performance from the company Capelle‐Blancard and Monjon (2012) by identifying three main perspective, and the financial effect of shareholder activism initiatives. research themes in the SRI literature and presenting visual evidence Regarding ESG metrics, there is a strong argument that the quality of the prevalent disconnection in the literature. This review also and reliability of ESG metrics need to improve. The role of ESG metrics support the findings of Friede (2019) by presenting new insights into as a proxy of sustainability performance is highly prominent in empir- the importance of ESG metrics, as demonstrated by their vital role as ical studies in the SRI performance theme. However, there are two a proxy for sustainability performance and an enabling factor of the main measurement problems with ESG metrics: lack of transparency SRI market. These findings, along with the future research 634 WIDYAWATI opportunities identified, are intended to enhance the theoretical and empirical understanding of SRI that is essential for the future development of SRI. ACKN O WLE DGM EN TS The earlier version of this review paper has been presented at the 2017 European Business Ethics Network (EBEN) Annual Conference. The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of the conference for the valuable feedback. The author would also like to thank Professor Tom Smith and Professor Martina Linnenluecke for their continuous support as advisory team of the author's PhD program. The author receives financial support for the PhD from Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Scholarship (LPDP RI) under a doctoral degree scholarship. This paper is part of the author's PhD thesis. CONFLICT OF INTE REST The author declares that she has no conflict of interest. ENDNOTES 1 U.S. SIF: The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, previously known as U.S. Social Investment Forum, is a U.S.‐based membership association that act as the non‐profit hub for the SRI in the United States.Eurosif is the leading association for the promotion and advancement of SRI in Europe. OR CI D Luluk Widyawati https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5626-0627 REFE RENCES Anand, P., & Cowton, C. J. (1993). The ethical investor: Exploring dimensions of investment behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology, 14(2), 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167‐4870(93)90007‐8 Arjaliès, D.‐L. (2014). Challengers from within economic institutions: A second‐class social movement? A response to Déjean, Giamporcaro, Gond, Leca and Penalva‐Icher's comment on French SRI. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(2), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐ 013‐1811‐2 Auer, B. R. (2016). Do socially responsible investment policies add or destroy European stock portfolio value? Journal of Business Ethics, 135(2), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐014‐2454‐7 Avetisyan, E., & Hockerts, K. (2017). The consolidation of the ESG rating industry as an enactment of institutional retrogression. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(3), 316–330. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bse.1919 Ballestero, E., Bravo, M., Pérez‐Gladish, B., Arenas‐Parra, M., & Plà‐ Santamaria, D. (2012). Socially responsible investment: A multicriteria approach to portfolio selection combining ethical and financial objectives. European Journal of Operational Research, 216(2), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2011.07.011 Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2006). Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 27(11), 1101–1122. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/smj.557 Bauer, R., Derwall, J., & Otten, R. (2007). The ethical mutual fund performance debate: New evidence from Canada. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐006‐9099‐0 Bauer, R., Koedijk, K., & Otten, R. (2005). International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(7), 1751–1767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004. 06.035 Bauer, R., & Smeets, P. (2015). Social identification and investment decisions. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 117, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.06.006 Beal, D. J., Goyen, M., & Phillips, P. (2005). Why do we invest ethically? Journal of Investing, 14(3), 66–77. Benson, K. L., Brailsford, T. J., & Humphrey, J. E. (2006). Do socially responsible fund managers really invest differently? Journal of Business Ethics, 65(4), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐006‐0003‐8 Benson, K. L., & Humphrey, J. E. (2008). Socially responsible investment funds: Investor reaction to current and past returns. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(9), 1850–1859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007. 12.013 Berry, T. C., & Junkus, J. C. (2013). Socially responsible investing: An investor perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(4), 707–720. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10551‐012‐1567‐0 Bird, R., Momenté, F., & Reggiani, F. (2012). The market acceptance of corporate social responsibility: A comparison across six countries/regions. Australian Journal of Management, 37(2), 153–168. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0312896211416136 Bollen, N. P. B. (2007). Mutual fund attributes and investor behavior. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 42(3), 683–708. https://doi. org/10.1017/S0022109000004142 Borgers, A., Derwall, J., Koedijk, K., & ter Horst, J. (2013). Stakeholder relations and stock returns: On errors in investors' expectations and learning. Journal of Empirical Finance, 22, 159–175. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jempfin.2013.04.003 Borgers, A., Derwall, J., Koedijk, K., & ter Horst, J. (2015). Do social factors influence investment behavior and performance? Evidence from mutual fund holdings. Journal of Banking & Finance, 60, 112–126. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.07.001 Brammer, S., Brooks, C., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures. Financial Management, 35(3), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755‐053X. 2006.tb00149.x Brzeszczyński, J., & McIntosh, G. (2014). Performance of portfolios composed of British SRI stocks. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(3), 335–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐012‐1541‐x Busch, T., Bauer, R., & Orlitzky, M. (2016). Sustainable development and financial markets: Old paths and new avenues. Business & Society, 55 (3), 303–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315570701 Cabello, J. M., Ruiz, F., Pérez‐Gladish, B., & Méndez‐Rodríguez, P. (2014). Synthetic indicators of mutual funds' environmental responsibility: An application of the reference point method. European Journal of Operational Research, 236(1), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor. 2013.11.031 Capelle‐Blancard, G., & Monjon, S. (2012). Trends in the literature on socially responsible investment: Looking for the keys under the lamppost. Business Ethics: A European Review, 21(3), 239–250. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1467‐8608.2012.01658.x Capelle‐Blancard, G., & Monjon, S. (2014). The performance of socially responsible funds: Does the screening process matter? European Financial Management, 20(3), 494–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468‐ 036X.2012.00643.x Chatterji, A. K., Levine, D. I., & Toffel, M. W. (2009). How well do social ratings actually measure corporate social responsibility? Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 18(1), 125–169. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1530‐9134.2009.00210.x WIDYAWATI Cheng, M. M., Green, W. J., & Ko, J. C. W. (2015). The Impact of Strategic Relevance and Assurance of Sustainability Indicators on Investors’ Decisions. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34(1), 131‑162. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50738 635 Derwall, J., Koedijk, K., & Ter Horst, J. (2011). A tale of values‐driven and profit‐seeking social investors. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(8), 2137–2147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.01.009 Child, C. (2015). Mainstreaming and its discontents: Fair trade, socially responsible investing, and industry trajectories. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(3), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐014‐2241‐5 Diouf, D., Hebb, T., & Touré, E. H. (2016). Exploring factors that influence social retail investors' decisions: Evidence from Desjardins fund. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐ 014‐2307‐4 Chipeta, C., & Gladysek, O. (2012). The impact of socially responsible investment index constituent announcements on firm price: Evidence from the JSE. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 15(4), 429. Dorfleitner, G., Halbritter, G., & Nguyen, M. (2015). Measuring the level and risk of corporate responsibility—An empirical comparison of different ESG rating approaches. Journal of Asset Management, 16(7), 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1057/jam.2015.31 Cortez, M. C., Silva, F., & Areal, N. (2009). The performance of European socially responsible funds. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(4), 573–588. Dumas, C., & Louche, C. (2016). Collective beliefs on responsible investment. Business & Society, 55(3), 427–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0007650315575327 Cowton, C. (1999). Playing by the rules: Ethical criteria at an ethical investment fund. Business Ethics: A European Review, 8(1), 60–69. Cox, P., Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2004). An empirical examination of institutional investor preferences for corporate social performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1023/B: BUSI.0000033105.77051.9d Crifo, P., Forget, V. D., & Teyssier, S. (2015). The price of environmental, social and governance practice disclosure: An experiment with professional private equity investors. Journal of Corporate Finance, 30, 168–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.12.006 Crifo, P., & Mottis, N. (2016). Socially responsible investment in France. Business & Society, 55(4), 576–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0007650313500216 Cullis, J. G., Lewis, A., & Winnett, A. (1992). Paying to be good? U.K. ethical investments. Kyklos, 45(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐ 6435.1992.tb02104.x Durand, R. B., Koh, S., & Tan, P. L. (2013). The price of sin in the Pacific‐ Basin. Pacific‐Basin Finance Journal, 21(1), 899–913. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pacfin.2012.06.005 Eccles, N. S., & Viviers, S. (2011). The origins and meanings of names describing investment practices that integrate a consideration of ESG issues in the academic literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐011‐0917‐7 Edmans, A. (2011). Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(3), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.021 Escrig‐Olmedo, E., Muñoz‐Torres, M. J., & Fernández‐Izquierdo, M. Á. (2013). Sustainable development and the financial system: Society's perceptions about socially responsible investing. Business Strategy and the Environment, 22(6), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1755 Cummings, L. S. (2000). The financial performance of ethical investment trusts: An Australian perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 25(1), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006102802904 Friede, G. (2019). Why don't we see more action? A metasynthesis of the investor impediments to integrate environmental, social, and governance factors. Business Strategy and the Environment. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bse.2346 Cunha, F. A. F. d. S., & Samanez, C. P. (2013). Performance analysis of sustainable investments in the Brazilian stock market: A study about the corporate sustainability index (ISE). Journal of Business Ethics, 117(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐012‐1484‐2 Galema, R., Plantinga, A., & Scholtens, B. (2008). The stocks at stake: Return and risk in socially responsible investment. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(12), 2646–2654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin. 2008.06.002 de Colle, S., & York, J. G. (2009). Why wine is not glue? The unresolved problem of negative screening in socially responsible investing. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐008‐ 9949‐z Garfield, E. (2009). From the science of science to Scientometrics visualizing the history of science with HistCite software. Journal of Informetrics, 3(3), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2009.03.009 Déjean, F., Gond, J.‐P., & Leca, B. (2004). Measuring the unmeasured: An institutional entrepreneur strategy in an emerging industry. Human Relations, 57(6), 741–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0018726704044954 Delmas, M., & Blass, V. D. (2010). Measuring corporate environmental performance: The trade‐offs of sustainability ratings. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(4), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1002/ bse.676 Delmas, M., Etzion, D., & Nairn‐Birch, N. (2013). Triangulating environmental performance: What do corporate social responsibility ratings really capture? The Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0123 Demetriades, K., & Auret, C. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in South Africa. South African Journal of Business Management, 45(1), 1–12. Derwall, J., Guenster, N., Bauer, R., & Koedijk, K. (2005). The eco‐efficiency premium puzzle. Financial Analysts Journal, 61(2), 51–63. Derwall, J., & Koedijk, K. (2009). Socially responsible fixed‐income funds. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 36(1–2), 210–229. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1468‐5957.2008.02119.x Garfield, E., Pudovkin, A. I., & Istomin, V. S. (2003). Mapping the output of topical searches in the web of knowledge and the case of Watson‐ Crick. Information Technology and Libraries, 22(4), 183–187. Giamporcaro, S., & Gond, J.‐P. (2016). Calculability as politics in the construction of markets: The case of socially responsible investment in France. Organization Studies, 37(4), 465–495. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0170840615604498 Giamporcaro, S., & Pretorius, L. (2012). Sustainable and responsible investment (SRI) in South Africa: A limited adoption of environmental criteria. Investment Analysts Journal, 41(75), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 10293523.2012.11082541 Girerd‐Potin, I., Jimenez‐Garcès, S., & Louvet, P. (2014). Which dimensions of social responsibility concern financial investors? Journal of Business Ethics, 121(4), 559–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐013‐1731‐1 Glac, K. (2012). The impact and source of mental frames in socially responsible investing. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 13(3), 184–198. https:// doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2012.707716 Gond, J.‐P., & Boxenbaum, E. (2013). The glocalization of responsible investment: Contextualization work in France and Québec. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(4), 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐ 013‐1828‐6 636 Gregory, A., Matatko, J., & Luther, R. (1997). Ethical unit trust financial performance: Small company effects and fund size effects. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 24(5), 705–725. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/1468‐5957.00130 WIDYAWATI Kolstad, I. (2016). Three questions about engagement and exclusion in responsible investment. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12107 Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. (2018). 2018 Global Sustainable Investment Review. Kreander, N., McPhail, K., & Beattie, V. (2015). Charity ethical investments in Norway and the UK. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 28 (4), 581–617. Guay, T., Doh, J. P., & Sinclair, G. (2004). Non‐governmental organizations, shareholder activism, and socially responsible investments: Ethical, strategic, and governance implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:busi.0000033112.11461.69 Lee, D. D., Humphrey, J. E., Benson, K. L., & Ahn, J. Y. K. (2010). Socially responsible investment fund performance: The impact of screening intensity. Accounting and Finance, 50(2), 351–370. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1467‐629X.2009.00336.x Haigh, M., & Hazelton, J. (2004). Financial markets: A tool for social responsibility? Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/ 10.1023/B:BUSI.0000033107.22587.0b Lewis, A., & Mackenzie, C. (2000). Morals, money, ethical investing and economic psychology. Human Relations, 53(2), 179–191. Hallerbach, W., Ning, H., Soppe, A., & Spronk, J. (2004). A framework for managing a portfolio of socially responsible investments. European Journal of Operational Research, 153(2), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0377‐2217(03)00172‐3 Hart, T. A., & Sharfman, M. (2015). Assessing the concurrent validity of the revised Kinder, Lydenberg, and Domini corporate social performance indicators. Business & Society, 54(5), 575–598. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0007650312455793 Lobe, S., & Walkshäusl, C. (2016). Vice versus virtue investing around the world. Review of Managerial Science, 10(2), 303–344. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11846‐014‐0147‐3 Mackenzie, C., & Lewis, A. (1999). Morals and markets: The case of ethical investing. Business Ethics Quarterly, 9(3), 439–452. Martí‐Ballester, C. P. (2015). Investor reactions to socially responsible investment. Management Decision, 53(3), 571. Heinkel, R., Kraus, A., & Zechner, J. (2001). The effect of green investment on corporate behavior. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 36 (4), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676219 Maynard, T. (2008). Climate change: Impacts on insurers and how they can help with adaptation and mitigation. Geneva Papers on Risk & Insurance, 33(1), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave. gpp.2510154 Henke, H.‐M. (2016). The effect of social screening on bond mutual fund performance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 67, 69–84. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.01.010 McLachlan, J., & Gardner, J. (2004). A comparison of socially responsible and conventional investors. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:busi.0000033104.28219.92 Höchstädter, A. K., & Scheck, B. (2015). What's in a name: An analysis of impact investing understandings by academics and practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 449–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551‐014‐2327‐0 Michelson, G., Wailes, N., Van Der Laan, S., & Frost, G. (2004). Ethical investment processes and outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000033103.12560.be In, F., Kim, M., Park, R. J., Kim, S., & Kim, T. S. (2014). Competition of socially responsible and conventional mutual funds and its impact on fund performance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 44, 160–176. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.03.030 Irvine, W. B. (1987). The ethics of investing. Journal of Business Ethics, 6(3), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00382870 Nilsson, J. (2009). Segmenting socially responsible mutual fund investors. The International Journal of Bank Marketing, 27(1), 5–31. https://doi. org/10.1108/02652320910928218 Nofsinger, J., & Varma, A. (2014). Socially responsible funds and market crises. Journal of Banking & Finance, 48, 180–193. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.12.016 Jun, H. (2016). Corporate governance and the institutionalization of socially responsible investing (SRI) in Korea. Asia Pacific Business Review, 22(3), 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2015.1129770 Nollet, J., Filis, G., & Mitrokostas, E. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non‐linear and disaggregated approach. Economic Modelling, 52, 400–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. econmod.2015.09.019 Juravle, C., & Lewis, A. (2008). Identifying impediments to SRI in Europe: a review of the practitioner and academic literature. Business Ethics: A European Review, 17(3), 285‑310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐ 8608.2008.00536.x Ortas, E., Moneva, J. M., Burritt, R., & Tingey‐Holyoak, J. (2014). Does sustainability investment provide adaptive resilience to ethical investors? Evidence from Spain. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐013‐1873‐1 Kappou, K., & Oikonomou, I. (2016). Is there a gold social seal? The financial effects of additions to and deletions from social stock indices. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(3), 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551‐014‐2409‐z Ortas, E., Moneva, J. M., & Salvador, M. (2012). Does socially responsible investment equity indexes in emerging markets pay off? Evidence from Brazil. Emerging Markets Review, 13(4), 581–597. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ememar.2012.09.004 Kempf, A., & Osthoff, P. (2007). The effect of socially responsible investing on portfolio performance. European Financial Management, 13(5), 908–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468‐036X.2007.00402.x Paetzold, F., & Busch, T. (2014). Unleashing the powerful few: Sustainable investing behaviour of wealthy private investors. Organization & Environment, 27(4), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1086026614555991 Knoll, M. S. (2002). Ethical screening in modern financial markets: The conflicting claims underlying socially responsible investment. The Business Lawyer, 57(2), 681–726. Kocmanova, A., & Simberova, I. (2012). Modelling of corporate governance performance indicators. Engineering Economics, 23(5), 485–495. Kocmanová, A., & Šimberová, I. (2014). Determination of environmental, social and corporate governance indicators: Framework in the measurement of sustainable performance. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 15(5), 1017–1033. https://doi.org/ 10.3846/16111699.2013.791637 Peifer, J. L. (2014). Fund loyalty among socially responsible investors: The importance of the economic and ethical domains. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(4), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐013‐1746‐7 Pérez‐Gladish, B., Benson, K., & Faff, R. (2012). Profiling socially responsible investors: Australian evidence. Australian Journal of Management, 37(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896211429158 Principles for Responsible Investment. (2017). The SDG investment case. Rathner, S. (2013). The influence of primary study characteristics on the performance differential between socially responsible and conventional 637 WIDYAWATI investment funds: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(2), 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐012‐1584‐z Renneboog, L., Ter Horst, J., & Zhang, C. (2008a). The price of ethics and stakeholder governance: The performance of socially responsible mutual funds. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(3), 302–322. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2008.03.009 Renneboog, L., Ter Horst, J., & Zhang, C. (2008b). Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(9), 1723–1742. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.12.039 Renneboog, L., Ter Horst, J., & Zhang, C. (2011). Is ethical money financially smart? Nonfinancial attributes and money flows of socially responsible investment funds. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 20(4), 562–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2010.12.003 Rivoli, P. (2003). Making a difference or making a statement? Finance research and socially responsible investment. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(3), 271–287. Rosen, B. N., Sandler, D. M., & Shani, D. (1991). Social issues and socially responsible investment behavior: A preliminary empirical investigation. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 25(2), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1745‐6606.1991.tb00003.x Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569 Sandberg, J., Juravle, C., Hedesström, T. M., & Hamilton, I. (2008). The heterogeneity of socially responsible investment. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(4), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐008‐9956‐0 Sandbu, M. E. (2012). Stakeholder duties: On the moral responsibility of corporate investors. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(1), 97–107. Sauer, D. A. (1997). The impact of social‐responsibility screens on investment performance: Evidence from the Domini 400 social index and Domini Equity Mutual Fund. Review of Financial Economics, 6(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1058‐3300(97)90002‐1 Sievänen, R., Rita, H., & Scholtens, B. (2013). The drivers of responsible investment: The case of European pension funds. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(1), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐012‐1514‐0 Soler‐Domínguez, A., & Matallín‐Sáez, J. C. (2016). Socially (ir)responsible investing? The performance of the VICEX fund from a business cycle perspective. Finance Research Letters, 16, 190–195. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.frl.2015.11.003 Solomon, A., Solomon, J., & Suto, M. (2004). Can the UK experience provide lessons for the evolution of SRI in Japan? Corporate Governance: An International Review, 12(4), 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1467‐8683.2004.00393.x Sparkes, R., & Cowton, C. J. (2004). The maturing of socially responsible investment: A review of the developing link with corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 45–57. Statman, M. (2006). Socially responsible indexes. Journal of Portfolio Management, 32(3), 100–109. Statman, M., & Glushkov, D. (2009). The wages of social responsibility. Financial Analysts Journal, 65(4), 33–46. Stellner, C., Klein, C., & Zwergel, B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility and Eurozone corporate bonds: The moderating role of country sustainability. Journal of Banking & Finance, 59, 538–549. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.04.032 Vasudeva, G. (2013). Weaving together the normative and regulative roles of government: How the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund's responsible conduct is shaping firms' cross‐border investments. Organization Science, 24(6), 1662–1682. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0822 Viviers, S., & Eccles, N. S. (2012). 35 years of socially responsible investing (SRI) research—General trends over time. South African Journal of Business Management, 43(4), 1–16. Webley, P., Lewis, A., & Mackenzie, C. (2001). Commitment among ethical investors: An experimental approach. Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167‐4870(00)00035‐0 Scholtens, B. (2006). Finance as a driver of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551‐006‐9037‐1 Williams, G. (2007). Some determinants of the socially responsible investment decision: A cross‐country study. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 8 (1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560701296803 Schröder, M. (2007). Is there a difference? The performance characteristics of SRI equity indices. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 34(1–2), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468‐5957.2006.00647.x Wu, M. W., & Shen, C. H. (2013). Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: Motives and financial performance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(9), 3529–3547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbankfin.2013.04.023 Schueth, S. (2003). Socially responsible investing in the United States. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(3), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1023/ a:1022981828869 Semenova, N., & Hassel, L. G. (2015). On the validity of environmental performance metrics. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(2), 249–258. Sethi, S. P. (2005). Investing in socially responsible companies is a must for public pension funds—Because there is no better alternative. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(2), 99–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐004‐ 5455‐0 Sharfman, M. (1996). The construct validity of the Kinder, Lydenberg & Domini social performance ratings data. Journal of Business Ethics, 15 (3), 287–296. Xiao, Y., Faff, R., Gharghori, P., & Lee, D. (2013). An empirical study of the world price of sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐012‐1342‐2 How to cite this article: Widyawati L. A systematic literature review of socially responsible investment and environmental social governance metrics. Bus Strat Env. 2020;29:619–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2393