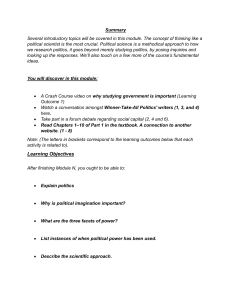

Summary Several introductory topics will be covered in this module. The concept of thinking like a political scientist is the most crucial. Political science is a methodical approach to how we research politics, it goes beyond merely studying politics, by posing inquiries and looking up the responses. We’ll also touch on a few more of the course’s fundamental ideas. You will discover in this module: A Crash Course video on why studying government is important (Learning Outcome 1) Watch a conversation amongst Winner-Take-All Politics' writers (1, 3, and 4) here. Take part in a forum debate regarding social capital (2, 4 and 6). Read Chapters 1–10 of Part 1 in the textbook. A connection to another website. (1 - 8) Note: (The letters in brackets correspond to the learning outcomes below that each activity is related to). Learning Objectives After finishing Module N, you ought to be able to: Explain politics Why is political imagination important? What are the three facets of power? List instances of when political power has been used. Describe the scientific approach. Define variables, concepts, and hypotheses. Describe falsifiability Describe frequent fallacies in argumentation. The course learning objectives 1 and 3 listed in the syllabus will have a direct bearing on this module. Crash-Course Notes Government – A set of rules and institutions that we set up in order to function as a unified society. As the crash-course series continues, we will discuss: The structure and functions of the branches of government. The division of power between the national government and state government. What are Political Parties? The videos that follow discuss a concept in political science theory that is not covered in your textbook. The first discusses collective action, while the second concentrates on the prisoner's dilemma as a specific illustration of a collective action difficulty (i.e., an obstacle to successfully acting collectively). There are two key ideas to remember from this. Second, we frequently find ourselves in circumstances where the short-term incentives push us away from collective action in ways that make us worse off in the long run than we would have been if we had cooperated. First, people working together will frequently achieve better outcomes than they do when they act individually. Chapter 1: What is Politics? - - Political scientists study politics in various forms, focusing on the city, state, national, or international issues. They typically focus on matters of consequence at the city, state, national, or international level. The definition of polite refers to any member of a political organization, including individuals, groups, corporations, unions, and politicians. It may include government programs, societal resources, access to rights, privileges, or tax breaks. Timing is crucial, since it can be as important as the thing itself. Political - - - scientists study the processes through which someone receives something in return, including democratic, un-democratic, fair, and institutional arrangements like constitutions, regulations, and laws. Lasswell’s definition of politics emphasizes the importance of getting, which implies making choices among competing interests and allocating resources or benefits among potential recipients. It is crucial to distinguish between zero-sum and win-win situations, as a benefit for one party may lead to a loss for others. In contrast, win-win situations involve balancing competing interests, such as granting freedom of speech or marrying a consenting adult. Politics is the authoritative and legitimate struggle for limited resources or precious rights and privileges within the context of government, economy, and society. It involves the number of resources with regularized, established, legal, and generally accepted procedures employed. Politics in the United States is often a chaotic and a painful clash of rooted interests, with some solutions favoring one set over others. Political Imagination - - Exercise your political imagination while reading this textbook to envision new ways to make the political system work for ordinary people. Ask “what if?” questions about requiring high school graduation, eliminating the nomination process, giving equal money to political causes, and requiring Supreme Court justices to have a law degree. This leads to envisioning a better future and realizing that our future is up to us. We can make new, hopefully better decisions by using imagination, organization, and action. Matthew Desmond and Walter Brueggemann emphasize the importance of political imagination in expressing discontent and the impermanence of the current social contract. Rob Hopkins' book, “From What Is to What If”, encourages readers to imagine positive, feasible, and delightful versions of the future before creating them. This approach can lead to better polity by transcending the status quo and envisioning a system that consistently serves all.