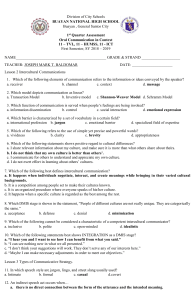

Formality Levels of Communication 1. Madrunio, et.al.(2011, p.19) asserts that “you have to consider all the variables in the communication process,” –this means that where the message is concerned, the formality level of language you use to encode the message must be appropriate to the person you are addressing—the receiver of the message and to context of the situation and culture. You use, for example, an informal style in parties and close friends of your age; but you use formal style in academic discussion in the classroom with your teachers and elders. 2. There are 5 formality levels of communication according to Martin Joas (1962 as cited by Antonio, et. Al., 2011, p.19) depending on your relationship with the person you address, the topic being discussed, and the occasion when the exchange takes place—also referred to as styles, these include the following: a. Frozen Style- This style occupies the highest rank in Joas’ classification, it is a style which is used in a very formal setting such as in rituals, church rites, speeches for state ceremonies, and some other occasions, called FROZEN, this style makes use of stock experiences that have not changes through the year. b. Formal Style This style is used in extended one-way communication like speeches in formal situations such as in a graduation ceremony; the sentences are complex and the words chosen are not those used in casual conversations. c. Consultative Style This style is used in semi-formal communication situations where, as its name goes a transition of some sort takes place (e.g. when patient goes to a doctor for a check-up). The interaction that takes place has 2 features: (1) one speaker supplies background information and she/he does not assume that she/he will be easily understood by the doctor; (2) the addressee participates continuously—in this situation, both participants are active, that us, when one speaks, the other gives short responses or signals that she/he is listening and can follow what is being said. Example: The following conversation shows the consultative style of interpersonal exchanges (Litao,et., al., 2011,p.19) Sophia: “Good morning, Dr. Luna. I have a high-grade fever and my head aches since yesterday.” Dr. Luna: “Hmmm, what medicines did you take?” Sophia: “Ohh, just this morning, I took one tablet of paracetamol.” Dr. Luna: “Yes, that will do. Also take this medicine I will give you.” Sophia: “Uh huh, so I need not undergo laboratory test?” Dr. Luna: “Yes, that’s right. We will observe you first for three days.” Sophia: “Thanks.” Note: Examples of consultative code-labels are “yes”, uh-huh”, that’s right”, “Oh, I see”, “Yes, I know”, “Well” and a few others that are used to distinguish roles of the listener and speaker. d. Casual Style This us used among friends and acquaintances in informal situations like in the canteen or when the students chat; it can also be used to address a stranger if the speaker wants to treat him or her as an insider. 1. Ellipsis This is one of the features of the casual style; ellipsis is the omission of some words in utterances. Example: “I believe that I can help you with that.” (Consultative style) “Of course, I can help you.” (Casual style) 2. Slang Refers to the non-standard words or expressions, which are known and used by certain groups: teenager groups, student’s groups, jazz music players, etc. Example: A young female is called “a girl” in standard language but in slang she may be referred to as “a chick” e. Intimate Style This is a completely private language that us used within the family and with very close friends, usually the intimate group is a pair; it excludes public information and shows a very close relationship between or among the interactants; the jargon or any vocabulary associated with the group is a feature of this particular style. Example: “Honey bunch” “babes” “sweetheart” “dear” “cupcakes” Speech Act Theory and Communication 1. Communication would sometimes bog down and misunderstanding crops up now and then. Why? That’s because Austin and Searle (1969 is cited by Antonio, et.,al., 2011,p.20) point out, when we speak, there are three things that have to be considered: a. “What we said” This is called the locutionary force of our speech act; since the word location refers to “saying something,” the term locutionary force consist of the words in the messages. b. “What we do when we say it” This is called the illocutionary force (e.g. when a parent says to a child who did something unbecoming, “Why did you do it?” he could be asking for an explanation, in which case, the child would have to give reason to justify what he did. On the other hand, that same remark said by a parent to a child could be a censure or a rebuke indicating that the child was wrong to have done it, in which case, the child is expected to say he is sorry and will not do it again.) –The illocutionary force of that statement “why you do it?” could be asking explanation to justify what one did or censuring or rebuking the addressee and the expected response to those two intended meaning would be the perlocutionary force. So if the child just keeps quiet, then the parent may ask, “Why don’t you answer?” since neither of the expected responses was made. c. “What the expected response or reaction is to what we said” This is labeled as the perlocutionary force—so if the child just keeps quiet, then the parent asks “Why don’t you answer?” since neither of the expected response was made. Another concrete example is the statement “don’t go into the water.” This is locutionary act with distinct phonetic, systematic and semantic features; the speaker’s intention, which is to warn the person to not go into the water, is the illocutionary act with distinct phonetic, systematic and semantic features; the speaker’s intention,