Small Giants - Companies That Choose to Be Great Instead of Big

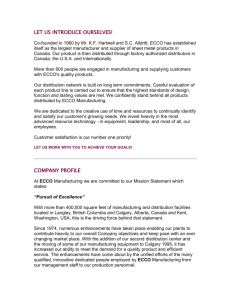

advertisement