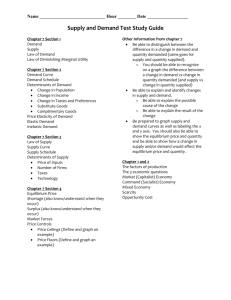

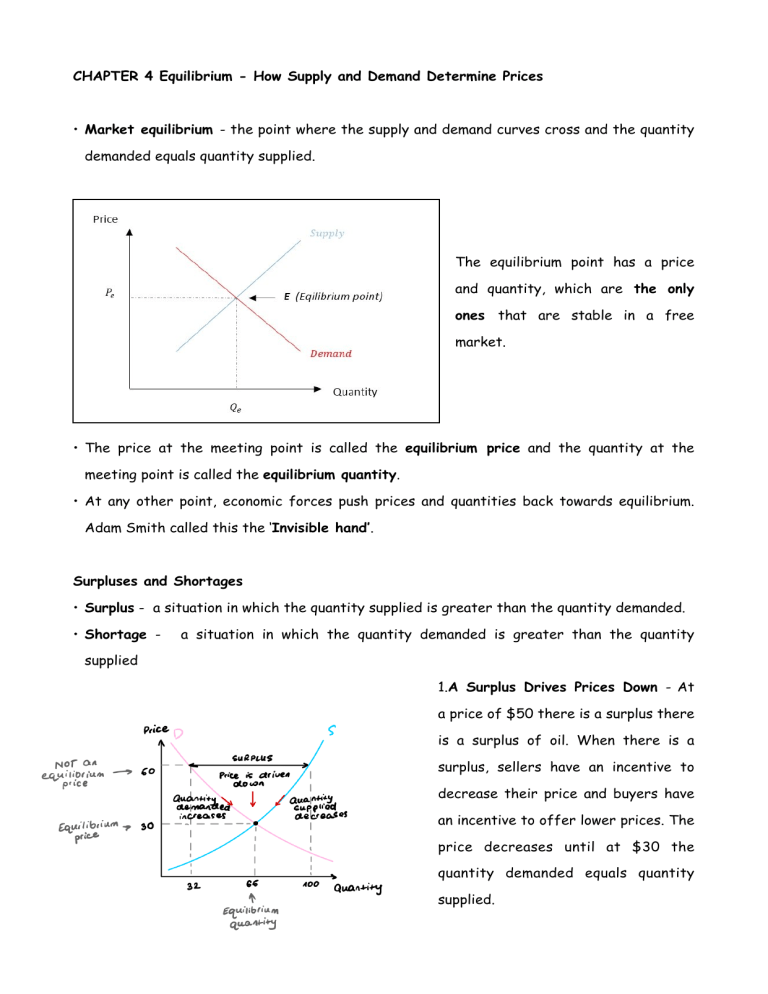

CHAPTER 4 Equilibrium - How Supply and Demand Determine Prices • Market equilibrium - the point where the supply and demand curves cross and the quantity demanded equals quantity supplied. The equilibrium point has a price and quantity, which are the only ones that are stable in a free market. • The price at the meeting point is called the equilibrium price and the quantity at the meeting point is called the equilibrium quantity. • At any other point, economic forces push prices and quantities back towards equilibrium. Adam Smith called this the ‘Invisible hand’. Surpluses and Shortages • Surplus - a situation in which the quantity supplied is greater than the quantity demanded. • Shortage - a situation in which the quantity demanded is greater than the quantity supplied 1.A Surplus Drives Prices Down - At a price of $50 there is a surplus there is a surplus of oil. When there is a surplus, sellers have an incentive to decrease their price and buyers have an incentive to offer lower prices. The price decreases until at $30 the quantity demanded equals quantity supplied. 2. A Shortage Drives Prices Up At a price of $15 there is a shortage of oil. When there is a shortage, sellers have an incentive to increase the price and buyers have an incentive to offer higher prices. The price increases until at $30 the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded and there is no longer an incentive for the price to rise. In general: • When there is a surplus (a situation in which the quantity supplied is greater than quantity demanded due to high prices), competition between producers will push the price down until the market equilibrium is found. If prices decrease, demand will increase, and supply will decrease. • When there is a shortage (a situation in which the quantity demanded is greater than the quantity supplied due to low prices), competition between consumers will push prices up. When prices rise, supply will increase, and demand will decrease. • At the market equilibrium the equilibrium price is stable because at the equilibrium price, the quantity demanded is exactly equal to the quantity supplied. Every buyer can buy as much as he wants and therefore do not have the incentive to push prices up, and every supplier can sell as much as he wants and will not have an incentive to push prices down. Who competes with whom? Although most people think that buyers compete with sellers, in reality buyers compete with other buyers and sellers compete with other sellers. Regardless of what sellers want, what they do when competing is lowering prices, buyers may want lower prices but what they do when hey compete is raising prices. A Free Market Maximises Producer plus Consumer Surplus (the Gains from Trade) Unexploited Gains • When quantity supplied is below the equilibrium quantity, buyers are willing to pay more than the minimum that the suppliers accept. In this case, there are unexploited gains. Wasted resources • When the quantity supplied is above the equilibrium quantity, there are wasted resources. In this case, the costs of sellers to produce an extra unit of a product is more than the worth of this extra unit to buyers. Therefore, the resources could be used better to produce something buyers are actually willing to pay. These two problems only exist for a short period of time because the free market will push the price and quantity to an equilibrium where producer and consumer surplus are maximised. When we say that a free market maximises the gains from trade, we mean three closely related things: 1. The supply of goods is bought by buyers with the highest willingness to pay. 2. The supply of goods is sold by the sellers with the lowest costs. 3. Between buyers and sellers, there are no unexploited gains from trade or any wasteful trades. Shifting Demand and Supply Curves 1. Increase in Supply 2. Decrease in Supply 3. Increase in Demand 4. Decrease in Demand Friedrich A. von Hayek (1945), “The Use of Knowledge in the Society The economic question of what the best way would be to allocate all available resources in society, is based upon the assumption that those that try to work on this problem possess all relevant data needed to solve this question through logical economic calculus. The real economic problem society faces is not merely the question of how to logically solve the problem of resource allocation, but also how to best utilise the relevant knowledge and bits of information which are dispersed among society and is impossible for a single mind to possess. “Planning” is defined as the decision related to the allocation of available resources. In this sense, all economic activity is planning. One of the main problems of economic policy is the question of how to most effectively utilise all this required knowledge which is initially dispersed among all people. The answer to this problem is closely related to the question of who should do the planning. The dispute is between whether planning should be done centrally, by one authority, or if it is to be divided among many individuals. The middle road between between central planning and decentralised planning by many individuals (competition) is the delegation of planning to organised industries, a monopoly. The effectiveness of these systems is to be measured by how well they utilise existing knowledge. It is often assumed that scientific knowledge is the sum of all knowledge. However, there exists a large body of very important but unorganised knowledge. This knowledge is not easily accessible by a central planner, but rather by individuals and can be characterised as practical knowledge rather than theoretical. Economic problems are always a product of change. If things continue as they were expected, there would be no need to form a new plan. Furthermore, small changes happen frequently and require constant small adjustments to be made by the “man on the spot”. These small changes and adjustments are not accurately reflected in the statistics which are drawn upon by the central planners and therefore inadequately considered when making central decisions. The economic problem of society is one of rapid adaptations to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place. Ultimate decisions should therefore be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances. The problem that arises is making sure that the “man on the spot” is also aware of the information that will allow him to fit his decisions into the whole pattern of changes in the larger economic system. The individual does not need to know all the causes of changes in his immediate surroundings, only the effects. This is where the price mechanism plays a role. A price can be seen as a numerical index, which communicates all the necessary knowledge related to its demand and supply, without overburdening the individual with unnecessary specifics. The price mechanism allows for information to be spread across the market in a highly efficient way. When for example a certain raw material becomes scarer, without an order being issued and without more than perhaps a handful of people knowing the cause of said scarcity, tens of thousands of people are made to use the material more sparingly, or in other words, to move in the right direction. The price mechanism extends the span of our utilisation of resources beyond the span of control of any one mind and allows the individual to do the desirable things without being told what to do. This is the concept which solves not only problems of an economic nature, but the central problem of all social science. Alfred Whitehead once said: “Civilisation advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them” The price system has made not only the division of labour possible, but also a coordinated utilisation of resources based on an equally divided knowledge.