273

THEDEVELOPMENTOFTHEUMTEDNATIONSLAW

CONCERNING PEACE-KEEPING OPERATIONS

1. INTRODUCTION

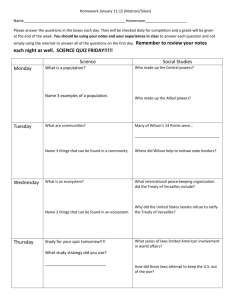

Especially as a consequence of the termination of the Cold War, the detente in the

relations between East en West (Gorbachev's 'new thinking' in foreign policy matters)

and, finally, the disappearance of the Soviet Union, the number of UN peace-keeping

operations substantially increased in recentyears. One could even speak of a'proliferation'.

Until 1988 the number of operations was twelve (seven peace-keeping forces: UNEF T

and 'II', ONUC, UNHCYP, UNSF (West New Guinea), UNDOF AND UNML; and

five military observer missions: UNTSO, UNMOGIP, UNOGIL, UNYOM and

UNIPOM). Now, three forces and seven observer missions can be added. The forces are

MINURSO (West Sahara), UNTAC (Cambodia) and UNPROFOR (Yugoslavia); the

observer groups: UNGOMAP (Afghanistan/Pakistan), UNIIMOG (Iran/Iraq), UNAVEM

Tand'IT (Angola), ONUCA (Central America), UNIKOM (Iraq/Kuwait) and ONUSAL

(El Salvador). UNTAG (Namibia), which was established in 1978, could not become

operational until 1989 as a result of the new political circumstances in the world. So, a

total of twenty-three operations have been undertaken, of which almost fifty percent was

established in the last five years, whereas the other half was the result of decisions taken

by the United Nations in the preceding forty years (UNTSO dates back to 1949). In the

meantime, some 'classic' operations are being continued (UNTSO, UNMOGIP,

UNFICYP, UNDOF, and UNTFIL), whereas some 'modern' operations already have

been terminated as planned (UNTAG, UNGOMAP, UNIIMOG, UNAVEM T and 'II',

and ONUCA). At the moment (July 1992) eleven operations are in action - the greatest

number in the UN history ever.

Now, the question here under consideration, is whether and to what extent this

proliferation has changed or innovated the concept of UN peace-keeping operations. Has

the model which was developed in broad outline in the past, remained unchanged or is

there a new type of peace-keeping operations? Of course, in this contribution I will deal

with the legal (international law) aspects of the matter, but it should not be overlooked

that the political developments of the concept of UN peace-keeping have been important.1

The relative simplicity of the framework of UN peace-keeping operations was a

characteristic of the past. They were mostly 'buffer forces' which had to control a cease1. See also J. Kaufmann, D. Leurdijk and N. Schrijver, The World in Turmoil: Testing the UN's Capacity,

ACUNS Report 1991-4, especially Chapter II.

Leiden Journal of International Law, Vol.5, No.2. Oct.'92

© 1992 Leiden Journal of International Law Foundation

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press

274

United Nations Law and Peacekeeping Operations

5 LJIL (1992)

fire between two neighbouring states (for example, UNEF T and 'II'), but sometimes

they operated within a country as a 'law and order force' (ONUC, UNFICYP). Mutatis

mutandis, the same could be said of military observer missions. When we analyse the

operations of the eighties and nineties, the striking feature is that their organizational

complexity has considerably increased. UNTAG, MINURSO, UNTAC and UNPROFOR

consist of acivil component, including civilian police ('civil police monitors') on the one

hand, as well as a military element, composed of infantry units (the peace-keeping force

stricto sensu) and military observers on the other hand. Civilian police monitors, who

came into action for the first time in Namibia, are a new element which is not directly

engaged in law and order tasks, but supervises how local police operate and whether they

do it in accordance with at least the minimum international standard (of human rights

protection). The growing complexity of UN peace-keeping operations is a consequence

of the fact that their present purpose often is to help implement a comprehensive peace

settlement. UNTAG (Namibia) was the first example in this respect (it was also

connected with UNAVEM T which monitored the withdrawal of Cuban troops from

Angola). In the Western Sahara, peace-keeping should lead to the holding of a

referendum about the territory's future status. UNTAG and MINURSO have (had)

functions within the framework of postponed decolonization processes. In Cambodia the

UN is even entrusted with the temporary administration of the country in preparation of

general elections. In this respect, the administrative role of UNTEA in West New Guinea

may be considered as a precedent. A general peace arrangement could also be agreed

upon with regard to Central America, where tasks were assigned to ONUCA and

ONUVEN (UN Observer Mission to Verify the Elections in Nicaragua), which was a

purely civilian operation. So, nowadays the general trend is to do as much peace-making

as possible (in the sense of the conclusion of peace treaties, etc.) before actually starting

peace-keeping in situ. In this perspective, peace-keeping does not serve so much to

'freeze' the situation in order to gain time for diplomatic negotiations, as to implement

a settlement and to stabilize the situation for the future. In the case of UNTAG,

MINURSO, and UNTAC -and the same applies to some observer missions (UNAVEM

'IT, see also ONUVEN)- 'electionmonitoring' within the framework of democratization

processes clearly has become a new UN activity, and so another trend becomes manifest:

UN involvement in internal affairs. In this connection, ONUVEH, which was an

independent civilian operation for the supervision of elections in Haiti (1990-91), should

be mentioned too. The most recent trend in Un peace-keeping is the military protection

of UN humanitarian relief operations by a peace-keeping force element and observers

(UNPROFOR in Sarajevo, and UNOSOM which is planned for Mogadishu, the capital

of Somalia).

So, modern UN peace-keeping covers a much broader spectrum of operational

activities than in the past, the combination of military and civilian components (law and

order, and administration) being a specific feature. Now, the question here to be answered

is whether innovations have occurred also in an international law perspective. Has the

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press

Siekmann

275

legal status of the host state changed, or may developments be noticed with regard to the

legal position of troop-contributing countries and in what respect?2 As is well-known,

written general rules for UN peace-keeping operations do not exist, so that legal

developments always have to be deduced from the ad hoc practice of operation

('adhocracy'). The general guidelines of the 'Committee of 33' (Special Committee on

Peace-Keeping Operations) are still in the drafting stage with part of the text being put

between square brackets.3 However, progress has been made with respect to the drafting

of a model status-of-forces agreement (with the host state) and a model participation

agreement (with troop-contributing countries). These model agreements are based upon

established practice.4 Now, analysis brings to light that the legal regime for UN peacekeeping operations has changed particularly in two essential respects: (a) the composition

of UN peace-keeping forces; and (b) the withdrawal of such forces.

2. THE COMPOSITION OF UN PEACE-KEEPING FORCES

With regard to the first two 'force-level operations', UNEF T and ONUC, a special

ground for the exclusion of UN member states from participation was put forward, i.e.,

permanent membership of the Security Council. 'Security Council permanent member

exclusion' remained in abeyance in the case of UNHCYP (Cyprus) and UNML

(Lebanon), in which the United Kingdom and France respectively took part. These had

been precisely the countries which, in part, had given rise to the principle, in connection

with UNEF T . The fact that the United Kingdom and France had been involved in the

Suez crisis as parties to the conflict was fortuitous. The exclusion of the then superpowers,

the United States and the Soviet Union, however, was of a structural nature. They were

by definition, directly or indirectly, politically involved in all conflicts in the world at

large. Cold War enmities should be kept out of the operation. If the Americans had

participated, the Soviets would undoubtedly have wished to participate, for which there

was no support whatsoever. So, the principle of 'Security Council permanent member

exclusion' was aimed at preserving the independence of the Force. The purpose of the

principle was also to avoid conflicts with the host country about the composition of the

Force.

It is true that the United Kingdom and France were closely involved in Cyprus and

Lebanon, but not as parties to the conflict, and in neither case were there objections from

the host country to participation by a permanent member of the Security Council. Nor

did the prospect of the United Kingdom and France occupying a special position with

2. See earlier R.C.R. Siekmann, Juridische aspecten van de deelname met nationale contingenten aan VNvredesmachten (Nederland en UNIFIL) (1988); English-language edition: National Contingents in United

Nations Peace-Keeping Forces, (1991). See also Basic Documents on United Nations and Related PeaceKeeping Forces (1989).

3. U.N. Doc. A/32/394 Annex II Appendix I, of December 2,1977.

4. U.N. Doc. A/45/594 of October 9, 1990 and U.N. Doc. A/46/185 of May 23, 1991.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press

276

United Nations Law and Peacekeeping Operations

5 LJIL (1992)

respect to the peace-keeping forces, as a result of their permanent seats in the Security

Council, appear to have been an objection. This position did, of course, enable those

countries to exercise their veto with respect to decisions affecting the operation. Since

the rationale of Security Council permanent member exclusion was to avoid conflicts

with the host country about participation by a permanent member it is probably going too

far to speak of exceptions to the rule in the case of British and French participations in

UNFICYP and UNIFEL. The rule seems simply to have been unapplicable, as the host

state itselfhad agreed to the participation of a permanent member of the Security Council.

The purpose of the principle would disappear, except that Security Council permanent

member exclusion was also based upon a quite different ground: the maintenance of the

independence of the peace-keeping force. If the host country itself requested the

participation of a permanent member, then it remained a special concern of the UN to

look to the independence of the Force with respect to its composition.

With regard to UNEF 'II' (1973-1979), Security Council resolution 340 contained

the decision to set up a United Nations Emergency Force, "to be composed of personnel

drawn from Member States of the United Nations except the permanent members of the

Security Council". Thus, for the first time, Security Council permanent member

exclusion was to be found expressly and imperatively in an enabling resolution.

However, no reasons were stated, and the inclusion of Security Council permanent

member exclusion was not unopposed. The host country, Egypt, had expressed the wish

that both the United States and the Soviet Union should participate in UNEF T . The

Soviet Union was for, but the United States was against. With regard to UNDOF

(established in 1974), the parties concerned, Israel and Syria, themselves had already

agreed that troops would be selected from UN member states who were not permanent

members of the Security Council. The Security Council confirmed this in its enabling

resolution.

At the time, the conclusion could be drawn on the basis of the 'classic' operations that

the absence of American and Soviet troops from UN peace-keeping forces would

probably continue, as long as one of the two opposed the participation of both. As far as

China, the fifth permanent member of the Security Council, was concerned, that country

had always abstained from actively taking part in the establishment of UN peace-keeping

operations. The principle of Security Council permanent member exclusion which

seemed to be absolute in nature, but which was never so, given its origin and rationale,

seems thus to have had such a narrow basis that it was correctly omitted from the draft

guidelines of the 'Committee of 33'.

What can be said about this principle with respect to the new peace-keeping

operations MINURSO, UNTAC and UNPR0F0R, all having a military force element?

MINURSO (Western Sahara) is in fact a 'single-nation force', for it will consist of only

one infantry battalion. In the past, the same could be said of UNSF in West New Guinea

(1962-63): only Pakistan supplied troops. It is obvious that in neither case the principle

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press

Siekmann

277

of permanent member exclusion was stated.5 As far as UNTAC in Cambodia was

concerned, the military component of this operation would be composed of twelve

infantry battalions. Nothing has been stated with regard to Security Council permanent

member exclusion.6 In this connection, it is noteworthy that mine-clearance units from,

inter alia, France, the United Kingdom as well as Russia participated in the UN Advance

Mission in Cambodia (UNAMIC). Then, France, the United Kingdom and Russia were

sounded out by the UN Secretariat about participation in UNTAC.7 UNPROFOR in

Yugoslavia would also consist of twelve infantry battalions. In this case, Security

Council permanent member exclusion was no longer an issue either.8 France and Russia

were asked to supply infantry units, the United Kingdom was requested to provide

logistics.9

So, the conclusion must be drawn that the principle of Security Council permanent

member exclusion is not existent any more. The mere fact that Russia has taken the place

of the Soviet Union in the Security Council should not automatically have led to this.

However, American objections against 'Russian' participation in UN peace-keeping

operations even with infantry units obviously do not hold any more, now that the Soviet

Union has disappeared as a superpower in world politics. Present 'Russian' participation

does not mean the 'Red Army in Blue Berets' the United States were afraid of in the past.

The Red Army will be distributed among the new Republics; separate Russian armed

forces will certainly be established, belonging to the Russian Federation as a sovereign

state. At this moment it is still unclear whether and to what extent former Red Army units

will survive as the Armed Forces of the Commonwealth of Independent States (maybe,

only the nuclear forces). The American attitude in this respect has even changed so

radically that they allow Russia to participate, even in Europe, and 'non-aligned'

Yugoslavia, not being a troop-contributing country themselves at the same time. Will this

be the future distribution of tasks between America and Russia: the former 'do' military

enforcement action on behalf of the UN (see Iraq/Kuwait), the latter contribute troops to

'consent forces' (UN peace-keeping)? It seems premature to draw such far-reaching

conclusions.

In connection with the present participation of Russia in UN peace-keeping operations

it should be mentioned that, in September 1988, the Soviet Union had already made a

5. See with regard to MINURSO: S. C. Res. 690 of April 29,1991, Para. 4, referring to U.N. Doc. S/22464,

Para. 48, at 11.

6. See S.C. Res. 745 of February 27,1992, Para. 2, referring to U.N. Doc. S/23613, Para. 85 sub (c), at 19.

7. See Letters of the Ministers of Defence and for Foreign Affairs to Parliament, Bijl.Hand. II1991/92 22300 X No.49, at 2, and No. 65, at 1.

8. See S. C. Res. 743 of February 21,1992, Para. 2,referringto U.N. Doc. S/23592, Para. 22, at 6. See also

U.N. Doc. S/23280 Annex III, Para. 3, at 15: "The military and police personnel required for the operation

would be contributed, on a voluntary basis in response to a request from the Secretary-General, by the

Government of Member States of the United Nations [...]".

9. Letter of the Ministers for Foreign Affairs and of Defence to Parliament, Bijl.Hand. II1991/92 - 22181

No. 19, at 1.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press

278

United Nations Law and Peacekeeping Operations

5 LJIL (1992)

stand-by offer for UN peace-keeping operations to the UN Secretary-General: "In

individual cases, if need be and if United Nations Member States display such interest,

the Soviet Union would be prepared to consider the question of providing its military

contingents as well".10This offer, which was made within the framework of Gorbachev's

v

new thinking', could already be considered as an application for participation in UN

peace-keeping forces, notwithstanding the Security Council permanent memberexclusion

principle.

Now that this principle definitely belongs to history, the composition of UN peacekeeping forces is only based on the 'accepted principle of equitable geographic

representation' which is generally applied to the composition of non-universal UN

organs, in which not all member states can be represented (peace-keeping forces may be

seen as subsidiary organs of the Security Council established under Article 29 of the UN

Charter). The starting-point for the application of this principle is that every region should

be represented, according to the following ratio: five Afro-Asian countries, one Eastern

Europe country (but in the traditional, political sense Eastern Europe does not exist any

more either!), two Latin American countries and two Western European (and other)

countries (has not become this category outdated too?). This principle can be explicitly

found also in the draft guidelines of the' Committee of 33' concerning UN peace-keeping

operations (Article 10). Now, MINURSO is a single-nation force, but with regard to

UNTAC and UNPROFOR the UN Secretariat obviously wanted to maintain a wellbalanced representation of member states as much as possible. In both cases a very large

number of countries (UNPROFOR: 31!) and from different regions were sounded out

about participation.'' Moreover, it is remarkable that countries from the very region were

asked, whereas this was avoided in the past, at least in respect of the Middle East, where

most operations took place.

3. THE WITHDRAWAL OF UN PEACE-KEEPING FORCES

A fundamental characteristic of UN peace-keeping forces is the condition that they be

based on host state consent. In his plan for the setting up of the first UN peace-keeping

force in history, UNEF T , Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold made the following

important observation:

While the General Assembly is enabled to establish the Force with the consent of those

parties which contribute units to the Force, it could not request the Force to be stationed

or operate on the territory of a given country without the consent of the Government of

that country.12 [italics in the original]

10. U.N. Doc. A/43/629 sub II, at 5 (Aide-memoire "Towards comprehensive security through the

enhancement of the role of the United Nations").

11. The applicability of the principle has been explicitly confirmed also with regard to UN observer missions

(UNIIMOG: U.N. Doc. S/20093, Para. 4(d)); UNIKOM: U.N. Doc. S/22454, Para. 4(d)).

12. U.N. Doc. A/3302 of November 6,1956 (UNEF T was established by the General Assembly; the same,

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press

Siekmann

279

The question was what this starting-point would mean in respect of the termination of an

operation. Should a UN peace-keeping force be automatically withdrawn as soon as the

host state as the sovereign, territorial state would demand that, or should the final decision

be taken by the UN? And what criteria should be applied in this context? Should the UN

withdraw their units only after the completion of the mandate of the operation? Was the

impracticability of the mandate a valid reason for a decision to withdraw a Force?

Real life had to give the answer and that is what happened in 1967, when President

Nasser of Egypt demanded the departure of UNEF T from the Sinai. UN SecretaryGeneral U Thant immediately agreed, referring to the fact that the operation was based

on host state consent and that Egypt had always assumed that a request for withdrawal

would be accepted by the UN. At the time, U Thant tried to justify his policy in a detailed

report, because he was criticized for his 'precipitous' decision. In that report he rejected

as purely private a memorandum in which Hammarskjold gave an interpretative account

of his talks with Nasser at the start of the operation:13 In that account Hammarskjold

concludes that in fact agreement was reached not to terminate the operation as long as

its mandate had not been fulfilled. The so-called 'good faith* aide-memoire, which was

the basis for the stationing of UNEF T , should be understood in this sense.14

Of course, U Thant created an important precedent by accepting Nasser's request

without any form of protest. This precedent had a very strong influence, especially from

a psychological point of view, on Governments who came to the conclusion that the UN

have a very weak legal position in terms of continuing an operation against the wishes

of the host state. This effect of U Thant's decision was also a consequence of the fact that

after UNEF T there were no practical problems on this point. ONUC was terminated by

a decision of the UN General Assembly, which stopped financing the operation (so, the

General Assembly may use its budgetary powers ex Article 17, Paragraph 2, of the

Charterto 'enforce' withdrawal!). UNEF 'II' came to an end in 1979, because the Soviet

Union threatened to veto proposals to give this operation tasks for the implementation

of the Camp David accords (Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel). Now, since 1982,

these tasks are fulfilled by the MFO, a non-UN operation, in the Sinai.

More or less in reaction to the UNEF T precedent, two measures were taken in order

to strengthen the legal position of the UN at least in a formal sense. In the first place, the

duration of the mandate was no longer left indefinite as was the case with UNEF T and

ONUC, but, starting from UNFICYP, all UN peace-keeping forces were established for

an 'initial period' of usually six months which could be prolonged by decision of the

Security Council with the consent of the host state. Secondly, the provision was made that

of course, holds true for operations established by the Security Council, which is the normal pattern in

modem times).

13. U.N. Doc. A/6730 Add. 3 of June 26,1967, Para. 73.

14. HammarskjSld's aide-memoire was published in I.L.M. 595 (1967); for the 'good faith' aide-memoire

see U.N. Doc. A/3375 Annex of November 20,1956. See for an interesting commentary on this question

J.I. Garvey, United Nations Peacekeeping and Host State consent, AJIL 241-269 (1970).

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press

280

United Nations Law and Peacekeeping Operations

5 LJIL (1992)

it should be the Security Council that has the power to decide about the 'premature'

withdrawal of a force. The following general formula was chosen for this purpose: "All

matters which may affect the nature or the continued effective functioning of the Force

will be referred to the Council for its decision".15 In this way, it was made clear that the

withdrawal of peace-keeping forces was not to be considered as a matter for unilateral

decision by the host state. This was done, however, by laying down only a general

guideline (cf., the use of the word 'will'), which was not a hard-and-fast legal rule. By

the continuation of the mandate each time with the consent of the host state for relatively

short periods, it was indicated in an indirect way that the host state each time concluded

a 'contract' with the UN for a new period, not to be cancelled one-sidedly.

The latest development with regard to this aspect of UN peace-keeping occurred in

connection with the setting up of UNPROFOR. In Resolution 743 of February 21,1992

the Security Council decided that the Force was established for an initial period of twelve

months, "unless the Council subsequently decides otherwise" (italics added). From both

implementation reports of the UN Secretary-General, on which UNPROFOR is based

and which were explicitly approved by the Security Council, it appears that the peacekeeping force will remain in Yugoslavia "until a negotiated settlement of the conflict was

achieved". Only if the parties concerned have confidence that this will indeed be the case,

the operation will succeed. Fears that it might be precipitately withdrawn before the

underlying problems had been peacefully resolved would have a most unsettling effect

in the UN protected areas, it is said in the second report. Therefore, the Secretary-General

proposed the provision in Resolution 743 that UNPROFOR could be withdrawn before

die initial 12-month period was completed only if the Council itself took a specific

decision to that effect.'6

The decision of the Security Council does not only contain an obligation for the UN,

but also for the parties concerned. In the preamble of the resolution explicit mention is

made of Article 25 of the UN Charter. Strictly speaking, this would mean that only

Yugoslavia as an official UN member state is bound by the provision on withdrawal Article 25 provides that the Members of the United Nations agree to accept and carry out

the decisions of the Security Council in accordance with the present Charter- but as soon

as Croatia, on the territory of which the UN troops would be stationed, would be admitted

to UN membership, this country would also be bound in a legal sense by the resolution.

It was Yugoslavia that requested for a peace-keeping operation on November 26,1991

('host state consent'). It is true that in the meantime Croatia was officially recognized by

dozens of countries, including the EC Member States, but in a UN perspective Croatia

is not more than a de facto party to the conflict. This also was illustrated by the fact that

the UN, which is now a UN member too, concluded a SOFA (Status of Forces

Agreement) with Yugoslavia only.

15.5eewith regard toUNEF'H',UNDOFandUNIFIL:U.N.Doc.S/11052/Rev.l and S/12611,Paras.4(a).

16. U.N. Doc. S/23280 Annex III, at 15 under the heading 'General principles', and S/23592, Paras. 2930.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press

Siekmann

281

A piquant detail in this question is that -as the present author knows from personal

experience- for Yugoslavia ('Belgrade') it was of great importance to formally exclude

the possibility of a premature withdrawal of UNPROFOR on the demand of Croatia (in

that case the Serbian minority would be left unprotected without a political settlement

having been reached). Belgrade was simply afraid of a repetition of the UNEF T

precedent from 1967. So, one would suppose that it was a very easy job for the UN to

get Yugoslavia, as the official host state for UNPROFOR, accept a restriction of its

sovereignty on this point, where it concerns territory which was'occupied' by Croatia.

The UN then, skilfully took advantage of the legal and factual circumstances of the

moment. The progressive development of the concept of UN peace-keeping has been

'adhocracy' also in the legal field. Dag Hammarskjdld and his advisers were already

clever diplomats in this respect and used the chances with regard to the setting up of

UNEF T and ONUC.

The conclusion must be that the guideline saying that it is the Security Council that

finally decides about the termination of an operation, now has been transformed into a

legal decision. It should not be forgotten, however, that this 'rule' only applies to

UNPROFOR so far, future developments remain to be seen. Generally speaking, it is

positive that 'host state consent' is restricted further in this way. If the UN are prepared

to invest such a large amount of man-power and money in order to make a peace-keeping

operation possible, it is unacceptable that a force should be withdrawn at the mere

demand of the host state, which had requested for military assistance itself! What then

is left of the UN's special responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and

security? It is desirable that a clear provision about the termination of peace-keeping

operations be included in the text of the draft guidelines of the 'Committee of 33*.

A final observation should be made in this context with regard to UNIKOM, which

was stationed between Iraq and Kuwait after the Gulf War.17 This operation was set up

on the basis of cease-fire Resolution 687 of the Security Council under Chapter VII of

the UN Charter and in Resolution 689 it is said that UNIKOM can only be terminated

by a decision of the Security Council. Iraq and Kuwait agreed to this. So, the reference

to Chapter VQ does not imply that UNIKOM is to be considered preventive (enforcement)

action. Moreover, its official mission is not to control only Iraqi behaviour along the

border with Kuwait. Finally, it has been explicitly provided for that the mission is not

authorized to use force ('physical action') to prevent violations of the cease-fire.

Robert Siekmann*

* Deputy Head, Public International Law Department, T.M.C. Asser Institute for

International Law, The Hague.

17. UNIKOM is an observation mission, to which an infantry element belongs (initially five companies, to

be replaced by one or more battalions, if necessary). This element has the special task of ensuring

UNIKOM's security (U.N. Doc. S/22454 of April 5,1991, Para. 9).

https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215650000251X Published online by Cambridge University Press