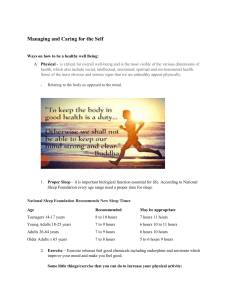

The Complex Relationship Between Healthiness, Happiness and Productivity in the Workplace By Samuel Höög It is a Thursday afternoon; I feel unfocused and distracted. 45 minutes later after a 30-minute run and a cold shower, I feel like a new person – unstoppable and full of happiness and productivity. Going for a run seems to be the ultimate cure for me, yielding such a large amount of happiness, healthiness and productivity. However, a couple of hours later I experienced hunger and lack of motivation, and the happiness has declined. It makes me wonder if the short-term effects of exercises, shopping, drinking alcohol, spending time with loved ones, or sleeping, that results in a happy, healthy and a productive life. Well, this a subjective proposition, but searching for an answer in scientific journals may give some understanding and evidence on how the relationships between healthiness, happiness and productivity functions. While it may initially seem obvious that happiness and healthiness correlate with productivity, further exploration suggests that happiness does not necessarily equate to productivity, nor does healthiness. The Healthy Worker The corporate athletes are exponentially growing and the idea of an overweight, or even a non-typical body type, is considered a “badge of shame”, as Nilofer Merchant argues. The two fitness-trainers who become management advisers also argue that to be at your “ideal performance state” the executives need to mimic life as a professional athlete. Train, eat healthy, drink water regularly, establish sleep regimes and stay mentally focused to visualize moments of peak performance, will help the executives to perform better with more persistent passion. Further, this has become a trend, and many companies encourage their employees to stay fit and healthy. For instance, some have used the so-called treadmill desk so ensure that employees stay active regardless of the workload. As a result, the differentiability between work and exercise erodes and blurs out the leisure exercise time (Cederström and Spicer, 2015). A time that could be used as a battery recharge to come back stronger and more productive. However, even if it may seem as the treadmill desk is a brilliant and effective exercise idea, Zygmunt Bauman points out that this fitness obsession rather may result in negative effects, such as 2 “perpetual self-scrutiny, self-reproach and self-deprecation, and so also of continuous anxiety” (Cederström and Spicer, 2015). Nevertheless, in the mind of the executives, the corporate fitness boom is considered as an advantage and contributes to more committed employees. But also, as the evidence from the Illinois workplace found out, that the employees who participated in the “iThrive” program showed lower medical spending and healthier behaviors compared to the non-participants (Jones et al, 2019). However, these effects were not due to the participation, but rather of the fact that the participants already were the healthier employees. Thus, one can argue that these wellness-programs should investigate the effects on low-income employees with high healthcare spending and poor health habits, in order to find significant effects. Further, the evidence from the research suggests that companies and managers may screen their workforce by implementing a wellness program in order to select the employees with better health habits to save medical spending and reduce costs (Jones et al, 2019). Maybe the focus on our healthy lifestyle is just a made-up industry. All these new innovations, such as the treadmill desk, may be an effective way for entrepreneurs to influence the employees and executives around the globe by planting the idea of fitness-workers in their minds. Looking closer at wellness-programs and innovations such as the treadmill desk, Cederström and Spicer (2015) argue that the estimates of wellness programs are often overestimated. One explanation for why companies are enthusiastic about corporate workouts is that making employees attend fitness routines helps a company create and sculpt the workforce, even though it may not have significant effects on wellbeing and productivity (Cederström and Spicer, 2015). A study made by Kathleen D. Vohs and Andrew C. Hafenbrack (2018) investigates the relationship between mindfulness and motivation in the workplace. A quite surprising result, showing that the meditation rather made the employees less motivated and spent less time and effort on assessments. It seems that the striving 3 of a healthy, both physically and mentally, employee is counterproductive, and the focus is rather on the human being outside of work than directly connected to the actual improvements of performance and productivity. Considering these findings there is no obvious relationship between healthiness and productiveness, despite the claims of the two fitness trainers who resettled as management advisors. Is the relationship rather reversed? Glancing over the article covering the Foxconn scandals, these employees were extremely productive, or at least worked endless hours. From the executives- and the board point of view these employees, regardless of how tragic it may seem, were always just bricks on a board who could be abused (Tam, 2009). A smoking, drinking, and amphetamine addict may be a more productive worker than a fitness-freak-employee. And as it may seem as these workers are replaceable and as it is displayed in the article about Foxconn, these workers who at extremes took their own life where simply replaced immediately by other who, with no hesitation, wanted the same role. It becomes more and more philosophical as the analyses of the relationship between healthiness and productivity gets deeper and deeper. The Happy Worker 24/7 capitalism is growing rapidly, and many employees are seen as a 24/7 asset. Crary (2013), discusses the 24/7 capitalism and points out how the military attempts to explore the scientific possibilities of how much the sleep of humans can be reduced, in a quest to achieve a super-efficient soldier. Further, he argues that profound uselessness and intrinsic passivity causes losses in production time, circulation, and consumption, and sleep collides with the demands of a 24/7universe. This has resulted in an almost five-hour decrease in sleeping time compared to the early twentieth century. Crary continues and describes how sleeplessness hastening the exhaustion of life and the depletion of resources. And as Marx called it “natural barriers”, sleep may be the only obstacle to the progression of 24/7 capitalism (Crary, 2013). 4 Sleep and sleeplessness may be a key factor to productivity, happiness and healthiness. As many studies show, a balanced sleep regime contributes to a healthier and happier lifestyle and enables the body to prevent infectious diseases, the occurrence and progression of several major medical illnesses including cardiovascular disease and cancer, and the incidence of depression (Irwin, 2015). A bad sleep routine can also bring about stress, which in turn affects the physical and mental health (Benham, 2009). Considering the psychological and scientific evidence of sleep and its effects on mental health, it is therefore most convenient to discuss the 24/7 capitalism as a danger towards our generation. However, as Crary advert sleep has become somewhat of a status case, and within the globalist neoliberal paradigm, sleeping is for losers. Along with the evolution of technology methods and motivations to accomplish the wrecking of sleep are fully in place (Crary, 2013). Contrary to the studies and evidence of the major positives of sleep, when the technologies and motivations of society come to a point where sleep is useless, why should anyone object if, for instance, new drugs could allow employees to work for 100 hours straight? A most fascinating thought one can argue. Alongside with the end of sleep, productivity may flourish as employees around the globe are able to work endless hours, but also sanction many hours of more leisure time for us to recharge and spend time with loved ones. Cederström (2018), in his article, “The Happy Fantasy”, discusses the technological innovations of the last decades that have allowed people to always work, blurring the line between work and personal life. Employees are now urged to think of work as an opportunity for discovering their true spirit. But when work has evolved into an abstract pursuit of happiness, employees may be left wondering where to draw the line. Now happiness has almost become an expected part of work as the socalled “emotional capitalism” is flourishing. Further, Cederström (2018) discusses the change in perception of work, from being an escape from boredom to an obligatory path to happiness. Hsieh, the founder of Zappos, points out that his perception of happiness has nothing to do with money nor success, but rather of creating, spending time with loved ones and eating his favorite food (Cederström, 5 2018). Which comes unsurprisingly. Asking people around you may certainly respond to you quite similarly as Hsieh pondered to the question, what makes you happy. Now the question becomes clear, whether happiness really makes you more productive and effective in the perspective of Human Resource Management and in the eyes of executives and the corporate board. Is it the healthy and fitnessfreak-employees that are always happy or is it the employees who work fewer overtime hours and spending time with loved ones that are happier, or maybe even more productive. It becomes almost a never-ending paradox, like the-chicken-andthe-egg dilemma. Conclusion The research shows that healthiness and happiness may not have a significant impact on the corporate employee productivity. Wellness programs and other corporate initiatives aimed at promoting health and well-being may not be a solution to find a productive worker. Hence the relationship between happiness, healthiness and productivity is not straightforward and other factors may have as much impact on workplace performance. In some cases, where the strive for healthiness and fitness may even evolve in negative thoughts and depression, which would result in an even more unhappy employee, and would most certainly result in a less productive worker. The obsession of the healthy and happy workforce may be a way of increasing a company’s validity and reliability. “We, as a company, care for our employees”. But the truth may be that the companies only care for the perception of a healthy and a happy workplace. Maybe the solution in the quest of productive workers and society lies in the belief of the 24/7 capitalism, where no one needs sleep and manage to work 100 hours straight and then spend 100 hours of leisure time. 6 References Benham Grant. 2009. Sleep: An Important Factor in Stress-Health Models. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/smi.1304 Retrieved 2023-04-23. Cederström, Carl. (2018) Happiness Inc. in The Happiness Fantasy, Cambridge: Polity. Cederström, Carl. and Spicer, André. 2015. The Health Bazaar, chapter 2 in The Wellness Syndrome. Crary, Jonathan. 2013. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. London: Verso Irwin R. Michael. 2015. Why Sleep Is Important for Health: A Psychoneuroimmunology Perspective. The Annual Review of Psychology. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115205 Retrieved 2023-04-23. Jones, Damon. Molitor, David. Reif, Julian. 2019. What Do Workplace Wellness Programs Do? Evidence from the Illinois Workplace Wellness Study. The Quarterly of Economics, 134(4): 1747-1791. Tam, Fiona. (2009) Foxconn factories are labor camps. South China Morning Post Vohs, Kathleen. D. and Hafenbrack, Andrew. C. 2018. Hey Boss, You Don’t Want Your Employees to Meditate. New York Times 7 8