Plato's Atlantis Myth: Minoan Civilization & Thera Eruption

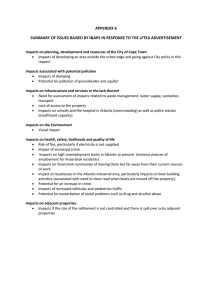

advertisement

Short Essay: Plato and the Myth of Atlantis. Ronnie Watt, 2014 Pseudo-history, pseudo-science, and pseudo-archaeology have delivered ‘proof’ of numerous sites where Atlantis, the lost city of which Plato wrote, could have thrived and then suffered total destruction in a cataclysmic event. For long it has been debated that Atlantis was not a factual civilisation but either counts as one of the many known myths of a destructive deluge, or merely serves as a metaphor for the Greek philosopher Plato to debate the consequences for a society that fails in its moral code of conduct. The extinction of Atlantis was linked in the late 1930s to a volcanic disaster that befell the island of Thera some 113 kilometres from Crete at a time when the Minoan civilisation flourished. Archaeology has revealed many features of Minoan society on Crete and its outpost colony on Thera that had distinct semblance to what Plato described in his Critias and Timaeus dialogues. There is also some corroborating evidence for a lost sea empire as depicted on the ‘Building Texts’ inscribed on the walls of the Temple of Edfu in Upper Egypt. Unlike Atlantis, Minoan Crete however did not “disappear in the depths of the sea” as described in Timaeus but that civilisation went into demise when it was hit by the after-effect earthquakes, tidal waves and of volcanic ash deposits of the volcanic eruption of nearby Thera. Plato’s Atlantis narrative is set out as a discussion on what constitutes the ideal government, between his teacher Socrates, the philosopher Timaeus from Italian Locri, Critias of Athens who as one of the Thirty Tyrants helped overthrow Athenian democracy, and the Syracusan statesman Hermocrates. The foundation on which the narrative is built, is a story told by an Egyptian priest to the Athenian statesman Solon, who in turn passed it down in the family of Plato. In essence, the Egyptian priest told how Poseidon created Atlantis for the protection of his lover Cleito who bore him ten sons. The city was a citadel surrounded by concentric rings of land separated by water. The descendants of the original sons of Poseidon strived to conquer new territories and in their quest engaged in a war with Egypt and Athens. The Greeks liberated the Atlantean territories but a natural catastrophe then occurred which destroyed ancient Athens and sunk Atlantis into the sea. There are many features of Atlantean society in Plato’s narrative that relate strongly to the archaeological evidence produced by the archaeologist Arthur Evans and his successors, about the Minoan civilisation on Crete and Thera. Atlantis, like Minoan Crete, had an advanced social structure, built its flourishing economy by means of maritime trading, practiced religious rites and ceremonies in temples that included bull sacrifices, and if not actually ruled by priests then the affairs of these two societies were guided by their priestly leaders. (Tschoegl, 1972:1,17; Hurd, 2012:23; Mifsud et al, 2012:14,52,54; Scott, 2012:http://saleonard.people.ysu.edu). If Thera is Atlantis, as the archaeological evidence supports, then there are discrepancies with Plato’s Atlantis. Thera is not located near the Straight of Gibraltar as in the case of Plato’s Atlantis, the Minoans traded in the eastern Mediterranean and Near East unlike Atlantis’ trading in the west, and the Minoans did did not wage war against Egypt. Modern geology has also disproved that a large landmass that could have been the site of Atlantis, ever existed where Plato situated it. (Scott, 2012:http://saleonard.people.ysu.edu) What Atlantis as per Plato’s narrative and Thera as per geological and archaeological evidence, have in common, is that both suffered an exceptionally severe natural disaster. It is now known for certain that the Thera volcano erupted in about 1450 BC at a time when the Minoan civilisation was at its height. The volcano smothered Thera in a thick layer of volcanic ash and triggered earthquakes and tidal waves that destroyed palaces and cities on nearby Crete, and to a lesser extent brought disaster on mainland Greece and elsewhere in the Mediterranean. One critical problem in equating Atlantis with Thera, is the dating of the disaster. According to the Plato, the original source of the narrative placed it at 9000 years before the time of Solon. Nicholas Tschoegl (1972:20) of the California Institute of Technology argues that in the transmission of the narrative to Plato, the numeral for 1000 became confused with that for 100. If the 9000 years are translated as 900 to which the 300 year period preceding Solon are added, the tally of time puts the extinction of Atlantis at about 1200 BC which is not far off the 1450 BC date which modern-day science has determined. It must also be kept in mind that though Thera was severely affected, the eruption did not decimate the Minoan civilisation which lingered on for another 250 years until about 1200 BC. Plato’s Critias and Timaeus dialogues are not lessons in geography and history, but the vehicle of philosophy and debate about piety, politics, and human nature (Scott, 2012:http://saleonard.people.ysu.edu). He might indeed have been familiar with a myth about a lost island civilisation, but used the myth as metaphor. Catalin Parternie (2014:http://plato.stanford.edu) of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Quebec, reminds us that Plato made use of existing myths, that he adapted and merged myths, or even invented myths, to serve his philosophical discourses. Scott (2012:http://saleonard.people.ysu.edu) speaks of Plato’s use of “serviceable lies” and “likely stories” through which his audience could relate to his philosophies. The Critias and Timaeus dialogues are positioned in a time of Athenian political turmoil and just before Athens launched her imperialistic Sicilian Expedition. In his The Republic, Plato had already named timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny as forms of unjust government and proposed that the rule by a philosopher-king would be the best hope for a harmonious and just city. (Hurd, 2012:16) It is against this background that Atlantis becomes the vehicle for Plato’s thinking about an orderly and just universe, rather than using Atlantis as a historical example of how greed and hubris will invoke the wrath of the gods. Atlantis is Plato’s metaphor for virtues, values and beliefs. (Scott, 2012:http://saleonard.people.ysu.edu) Plato’s Atlantis is for the most part the invention of a myth or an adaptation of a myth. His Atlantis does ring true in the sense that it presents a scenario in which a violent, natural disaster erased a Mediterranean civilisation such as that which indeed befell the Minoans on Theros and Crete. However, as has been shown, Plato could also have drawn on other narratives of deluge and destruction to construct his Atlantis. Whether by accident or by calling on feint memories of such an actual disaster in earlier Greek history, Plato’s Atlantis happened to become like the Minoan civilisation on Theros rather than to be the Minoan civilisation on Theros. Bibliography Hurd, Kimberley. 2012. The Lost City: Examining the Relationship Between Science, Philosophy and the Atlantis Myth. Louisiana State University. (O) Accessed 17 August 2014. Available at http://etd.lsu.edu/docs/available/etd-07052012-140651/unrestricted/Hurd.diss.pdf Mifsud, Anton & Sultana, Chris Agius & Ventura, Charles Savona. 2001. Malta: Echoes Of Plato’s Island. The Prehistoric Society of Malta. (O) Accessed 17 August 2014. Available at https://www.academia.edu/5519734/MALTA_AND_PLATOS_ATLANTIS Scott A. Leonard. 2012 (updated). A Closer Look: Is Plato’s Story of Atlantis a Myth? Youngstown State University. (O) Accessed 17 August 2014. Available at http://saleonard.people.ysu.edu/PlatosAtlantis.html Partenie, Catalin. 2014 (revised). “Plato’s Myths.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (O) Accessed 15 August 2014. Available at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plato-myths/ Plato. 360 BC. Critias. Translated by Jowett, Benjamin. 1871. In The Internet Classics Archive. (O) Accessed 16 August 2014. Available at http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/critias.html Plato. 360 BC. Timaeus. Translated by Jowett, Benjamin. 1871. The Internet Classics Archive. (O) Accessed 16 August 2014. Available at http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/timaeus.html Tschoegl, Nicholas. 1972. “Atlantis: Cradle of Western Civilization?” California Institute of Technology.” In Engineering and Science, Vol 35. (O) Accessed 15 August 2014. Available at http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/307/1/atlantis.pdf