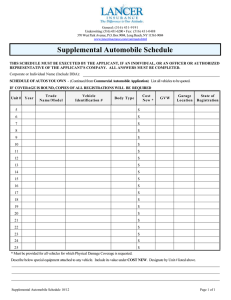

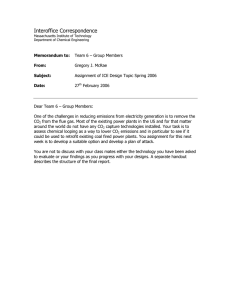

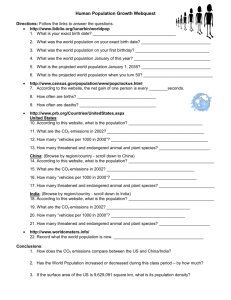

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254266242 Innovation and creativity in the automobile industry: Environmental proposals and initiatives Article in The Service Industries Journal · September 2011 DOI: 10.1080/02642069.2011.552976 CITATIONS READS 8 3,428 3 authors, including: Colin C Williams Amadeo Fuenmayor The University of Sheffield University of Valencia 993 PUBLICATIONS 22,367 CITATIONS 64 PUBLICATIONS 119 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Colin C Williams on 29 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE This article was downloaded by: [University of Sheffield] On: 16 August 2011, At: 03:15 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Service Industries Journal Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fsij20 Innovation and creativity in the automobile industry: environmental proposals and initiatives a b Colin C. Williams , Amadeo Fuenmayor & Sonia Dasí c a Management School, The University of Sheffield, University of Sheffield, UK b Departamento de Economía Aplicada, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain c Departamento de Dirección de Empresas Juan José Renau Piqueras, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain Available online: 19 Jul 2011 To cite this article: Colin C. Williams, Amadeo Fuenmayor & Sonia Dasí (2011): Innovation and creativity in the automobile industry: environmental proposals and initiatives, The Service Industries Journal, 31:12, 1931-1942 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2011.552976 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. The Service Industries Journal Vol. 31, No. 12, September 2011, 1931 –1942 Innovation and creativity in the automobile industry: environmental proposals and initiatives Colin C. Williamsa, Amadeo Fuenmayorb∗ and Sonia Dası́c a Management School, The University of Sheffield, University of Sheffield, UK; bDepartamento de Economı́a Aplicada, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain; cDepartamento de Dirección de Empresas Juan José Renau Piqueras, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 (Received 24 December 2010; final version received 4 January 2011) Environmental issues are demanding deep changes, both by governments as well as by the private sector through strategic management, across all sectors. This is particularly the case in the automotive services sector, where the need to reduce CO2 emissions has become a central target. In this paper, the researchers seek to evaluate these innovative initiatives. For this purpose, the main tax measures are analysed as well as the strategies being developed by automobile companies in the context of the European Union in general and Spain in particular. It is found that different public policies and managerial initiatives are being used to achieve this goal. Keywords: environment; automobile companies; public policies; innovation; European Union Introduction The problems of global warming and climate change are requiring creativity and innovation in both public policies as well as the managerial strategies adopted by companies. This is particularly the case in the automobile industry, the sector focused upon in this paper. Environmental policy in this industry draws on three main instruments. First, there is command and control regulation, which involves the enforcement of several behaviours related to pollution. This technique has sometimes proved effective, such as when the government introduced the compulsory use of catalysers or unleaded fuel. However, so far as emissions were concerned, this regulation could only work as a ceiling. The second instrument of environmental policy consists of emission permits. These are particularly appropriate instruments for stationary sources, and at the moment they are being used in the European Union in sectors with a relatively low number of emission sources (energy activities, mineral oil refineries, iron and steel industry, cement, glass and ceramic bricks, and pulp and paper) that represent around 40% of the total polluting emissions. For the pollution derived from the transport sector, however, this system does not seem adequate or appropriate. Third and finally, there is the instrument of environmental taxation. This instrument is particularly intended for the control of mobile sources. It can be used for emission control of those for which it is difficult and unfeasible to apply the license system, such as the transport, agricultural and residential sectors. In the realm of environmental taxation, the aim is to alter the automobile driver’s decisions and behaviour. Before a vehicle can be put on the road, and hence pollute, its ∗ Corresponding author. Email: amadeo.fuenmayor@uv.es ISSN 0264-2069 print/ISSN 1743-9507 online # 2011 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/02642069.2011.552976 http://www.informaworld.com Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 1932 C.C. Williams et al. owner should have made two important decisions. First, s/he must decide to acquire a certain vehicle; at this point, one could discourage this acquisition or motivate the choice towards a ‘clean’ vehicle. The current registration tax could contribute to this decision, with enough precision. The second decision relates to the daily use of the vehicle. In this respect, fuel tax has a direct relationship with its use. A third tax, the annual circulation tax, has a much weaker environmental impact, since it is located at a point temporally distant from the important decision (the decision of vehicle acquisition and its polluting capacity) or it does not depend on pollution (it does not depend on the use of the vehicle, but only on ownership). Government regulation constitutes a part of a group of political – legal factors that, jointly with sociological – cultural factors, deeply affect car-manufacturing companies’ approach to environmental issues. These companies, in order to adapt to environmental requirements, are pushed to use strategies to fulfil them. One of the most common strategies in the automotive sector, especially with regard to innovation and creativity, is the cooperation strategy or alliance between companies. In this strategy, different competitor companies, or companies and suppliers, share resources for a common goal. This strategy enables them to be much more flexible and more competitive. The objective of this paper is to evaluate these initiatives of the government and the automotive industry management, to adapt to a framework where environmental improvement prevails, in Europe in general and Spain in particular. In doing so, we have structured the paper as follows. In the second section, we analyse the economic treatment of pollution, through the category of externalities, and its treatment through internalization. The third section is then devoted to the analysis of the registration tax regulation, the consequences of their recent reform in Spain, as well as the criticisms levelled at this policy initiative. The fourth section, meanwhile, analyses the annual circulation tax, its environmental limitations, as well as its main changes. In the fifth section, fuel taxation is briefly explained, as well as its effect on fuel consumption and its influence on the consumer’s daily behaviour. In the sixth section, we expose the use of cooperation agreements by companies. The final section then provides a summary evaluation of the range of innovative initiatives available. Market externalities and their internalization through taxes From an economic point of view, environmental taxation is closely related to the category of externalities. Certain activities yield, besides from the expected results, either positive or negative externalities that are neither suffered nor enjoyed by the individual that carries out this activity. The most well-known example of negative externalities is pollution. As long as the person who decides on a certain activity (to drive a car) is not the same person that suffers the negative consequences (pollution), we expect the level of this activity will be higher than the optimum. The optimum level would be the one in which the polluter was suffering the consequences of this activity in full. Figure 1 shows the concept of externality. The x-axis represents the level of production or activity (in our case, it represents the use of a vehicle that pollutes). The y-axis represents the costs and benefits per unit derived from this activity. In this framework, the figure shows how the individual takes his/her decisions bearing in mind his/her own costs (PMC, or private marginal costs curve) and benefits (PMI, or private marginal income curve). Knowing that, s/he will choose the activity level X0 when his/her marginal benefits equal his/her marginal costs. Nevertheless, this activity simultaneously generates some externalities, in this case in the form of pollution, which means that the total costs Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 The Service Industries Journal 1933 Figure 1. Externalities and internalization. (those of the pollutant and those suffered by the rest of society) will rise until social marginal cost. As we take these social costs into account, we could see that in X0, total (social) costs are clearly bigger than the benefits. As stated, the individual who makes the decision will carry out the activity until the X0 level, bearing in mind his/her own costs and benefits. But if someone could take into account all the costs and benefits, namely the internal and the external ones, the optimum level of activity would be X∗ . From the economic point of view, the mechanism used to resolve externalities is called internalization. Through this process, an attempt is made to modify the behaviour of the generator of the externality in order to behave optimally. That is, an attempt is made to ensure that the generator would act as if s/he totally suffered the negative externality derived from the polluting activity. In cases where there are relevant negative externalities, the public intervention is justified, either through imperative command and control regulation, emission permits or environmental taxation, among other mechanisms of internalization. Based on Figure 1, through the internalization process, the assertion is that the generator of a negative externality (in this case the car driver) behaves as if s/he suffered all the consequences of his/her polluting activity. This is achieved through the introduction of a tax. The tax represents a cost to be imposed on the polluter, as a reflection of the negative externality that the activity generates. In Figure 1, a tax per unit would be introduced, equalizing the distance ab. This tax would imply a tax collection represented by the area p∗ p0ab. Doing so, the costs to the externality generator would move from PMC to PMC’ (the dotted line in the figure); the sum of his/her own cost and the tax that s/he has to pay. Facing these new costs, the pollutant will choose the level of activity X∗ , that is, the optimum. As can be seen, the key factor in the internalization process rests upon the change in the behaviour of the generator of the externality. From an environmental point of view, the purpose of the tax is to change the behaviour of the individual that carries out a polluting activity, with the tax collection a collateral consequence. The important point here is that the tax must be related in some way to the activity of the generator of the externality. A general tax, no matter if people pollute or not, cannot be considered an environmental tax, as it does not result in a change in the polluting activity. Although taxes on passenger cars are heterogeneous and diversified in the European Union, the following types can be distinguished (European Commission, 2002, p. 5): 1934 C.C. Williams et al. Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 (1) Taxes paid at the time of vehicle acquisition, or the first time the vehicle is put into service. These are generally called registration taxes. In Spain, this type of tax is named ‘Impuesto Especial sobre Determinados Medios de Transporte’ (IEDMT). (2) Periodic taxes paid in connection with the ownership of a passenger car, defined in most cases as yearly circulation taxes. These are paid due to the mere ownership of the car. In Spain, this tax is called ‘Impuesto sobre Vehı́culos de Tracción Mecánica’ (IVTM). (3) Taxes on fuel. In Spain, there are two taxes: the ‘Impuesto Especial sobre Hidrocarburos’ (IEH) that levies the consumption of fuel in the manufacture phase; and the much smaller ‘Impuesto sobre las Ventas Minoristas de Determinados Hidrocarburos’ (IVMDH), introduced in the retail phase. (4) Other minor taxes such as insurance taxes, registration fees, road user charges and road tolls. The registration tax In the European Union, there are seven countries (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Luxembourg, Slovakia, Sweden and the UK) that do not have any tax related to the acquisition of an automobile. In four countries (Italy, Lithuania, Poland and Slovenia), this tax is not related at all to CO2 emissions or other proxies, such as fuel consumption. The remaining 15 countries have a registration tax related to CO2 emissions or fuel consumption, either exclusively, or to other variables such as price, the engine’s cubic capacity or length.1 Changes in the Spanish registration tax In Spain, the registration tax is called IEDMT.2 The tax collection derived from this tax has been strongly reduced as a consequence of the 2008 tax change and the economic crisis, as noted in Table 1. The net tax due (gross tax due minus ‘PREVER Plan’ tax credit3) derived from the new tax is strongly reduced in comparison with previous years. The economic crisis has implied a reduction in car purchases. Nevertheless, the medium tax (total net tax divided per number of cars) has been strongly reduced too. Indeed, in 2006 and 2007, the average tax was, per car, respectively, 1222E and 1316E. But in 2008, this tax came down to 1004E (a 23.7% reduction per vehicle). This reduction has been sharpened even more in 2009, resulting in a tax of 790E (an additional reduction of a 21.3%), and the trend continued in 2010. Table 1. IEDMT tax collection. Year Gross tax due PREVER Tax credit Net tax due Var. (%) No. of vehicles Medium tax Var. (%) 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010∗ 2,037,509 2,066,649 1,077,554 708,315 452,938 183,960 133,196 – – – 1,853,549 1,933,453 1,077,554 708,315 452,938 – 4.3 244.3 234.3 – 1,516,271 1,469,416 1,073,675 896,304 625,460 1,222 1,316 1,004 790 724 – 7.7 223.7 221.3 28.3 Source: Agencia Tributaria. Gross tax due, PREVER tax credit (disappeared in 2008) and Net tax due are in thousands of Euros. Medium tax (total net tax divided per number of cars) data are in Euros. ∗ Unfinished year (January– August). Valid only for comparative purpose in the case of Average net tax due. The Service Industries Journal 1935 Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 The major change resulting from the new regulation or IEDMT was the new configuration of tax rates, as can be noted in Table 2. Until 2007, the tax rate was determined depending on the automobile’s engine cubic capacity. There was a reduced tax rate applied to cars up to 1600 cm3 for petrol engines, or 2000 cm3 for diesel engines. For higher cubic capacities, the tax rate rose up to 12%. Now, the new tax is directly related to the variable that we try to control: the CO2 emission per kilometre. In this way, four tax rates could be distinguished from a zero tax rate to 14.75%, depending on the official emissions of CO2. From this level, each autonomous region has the normative power to modify the tax rates, increasing them up to 15%. The 14.5% tax rate is applied to several special circumstances (vehicles that could not prove their emissions, camper vans, quad vehicles and jet skis). On the other hand, the 12% tax rate has a residual character (vehicles that do not have another tax rate, boats, aeroplanes, etc.). Effects of the changes in tax law on new registrations Our interest in the tax change here concerns the effect this reform could have on behaviour. As stated, the main goal of this kind of tax, as well as tax collection, is to change the behaviour of people as polluters. In this case, the tax intends to alter the purchase decisions of consumers, in order to have them choose less polluting vehicles. In other words, the tax pursues the internalization of the negative externality derived from pollution. Therefore, we expect that, if the tax reform has been properly designed, the composition of vehicle purchase will change, so that the proportion of less polluting vehicles (up to 120 g CO2/km) will rise due to the tax exemption; and the proportion of the higher polluting cars purchased will diminish. As can be seen in Table 3, the purchase decisions suffered a noticeable change as a consequence of the IEDMT reform. In a framework where there was a small reduction in total sales (6%), the acquisitions of cleaner cars (emissions below 120 g CO2/km) rose sharply between 2007 and 2008, yielding an increase greater than 38%. The next tax rate remains more or less at the same level, since it drops 3%, a little less than the total market. Nevertheless, the share corresponding to more polluting cars, which suffered the higher tax rates, has been strongly reduced: a 22% reduction in the case of passenger cars emitting between 120 and 160 g CO2/km, and more than 47% for the vehicles with a 14.75% tax rate (vehicles emitting more than 200 g CO2/km, with a higher tax rate than the previous tax). Viewing these data, there is no doubt that the tax reform has had the desired effect: the tax has discouraged the acquisition of high polluting vehicles, stimulating the purchase of environmentally cleaner passenger cars. However, these results must be treated with care for two reasons. On the one hand, the announcement effect: it is possible that higher pollutant vehicles were purchased before Table 2. IEDMT tax rates before and after the reform. Up to 31 December 2007 Tax rates 7% 12% Petrol Up to 1,600 cm3 More than 1,600 cm3 Diesel Up to 2,000 cm3 More than 2,000 cm3 From 01 January 2008 Tax rates Exempt Less than 120 Emissions: g CO2/km 4.75% 121 –160 9.75% 161–200 14.75% 12% More than 200 Remainder 1936 C.C. Williams et al. Table 3. Car registration by emission levels. Less than 120 g CO2/km 121– 160 g CO2/km 161–200 g CO2/km More than 200 g CO2/ km Exempt 4.75% 9.75% 14.75% Tax rates No. of registrations, Jan/Feb 2007 No. of registrations, Jan/Feb 2008 Total 28,936 12% 135,906 57% 51,735 22% 20,291 9% 236,868 40,075 18% 131,781 59% 40,059 18% 10,614 5% 222,529 Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 Source: Faconauto (2008). the law came into effect and that tax exempt car purchases were delayed after 2008. Should this be correct, the figures would only show the impact of the tax reform. We could check whether this hypothesis is correct or not, using Figure 2 that displays the market share on total sales corresponding to each vehicle-type segment. This figure reinforces the trends shown in Table 3 for future periods. The market share of exempt vehicles goes on rising, being slightly reduced in the case of more polluting automobiles. On the other hand, we could still think that the economic crisis has imposed its logic through changes in behaviour. In this way, citizens have protected themselves against the economic crisis by buying cheaper vehicles, concerned about both their acquisition and maintenance. Although the economic crisis could be partially responsible for this movement, it is beyond doubt that the consumption patterns have changed. Nevertheless, the environmental impact might have been more profound if the tax reform had been designed in a different manner. The tax rate design will create discontinuities: a vehicle emitting 120 g CO2/km would be tax exempt, whereas another one of 121 g CO2/km will be taxed to 4.75%. And this tax rate will remain unchanged up to 160 g CO2/km. In this sense, the design of a tax rate directly related to emissions would have implied minor distortions in purchases. The second criticism that has been made about the Spanish reform of IEDMT has to do with the tax base design, which is the magnitude that is multiplied by the tax rate in order Figure 2. Market share evolution according to emissions. Source: Agencia Tributaria. The Service Industries Journal 1937 to obtain the tax amount. In the IEDMT, the tax base is ad valorem. That is to say, the tax rate will be applied to the vehicle value, producing situations that do not make sense. An old, polluting and cheap car could pay a lower tax than a new, clean and expensive car. An important part of the tax could represent the comfort or security, characteristics that usually increase the vehicle price. It seems strange that using an ABS system or airbag devices will imply a higher registration tax. The IEDMT reform could have given environmental character to the tax base, defining it as the level of emissions, the grams of CO2 per kilometre, instead of the automobile price. Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 The annual circulation tax There is also a tax related to automobile ownership, the Annual Circulation Tax. In the European Union, only seven countries do not apply this tax (Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia). In nine countries (Cyprus, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Ireland, Sweden and the UK), the amount of the tax is related to CO2 emissions, fuel consumption or exhaust emissions. In the remaining 11 countries (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Romania and Spain), the tax depends on other variables not directly related to CO2 emissions, such as engine power, cylinder capacity, weight and type of fuel or the age of the vehicle.4 In Spain, the Annual Circulation Tax is called IVTM.5 This is a tax regulated by the state, but city councils can modify it, and are responsible for the tax collection. As in other countries, the IVTM is related to car ownership,6 instead of the use of it. This fact reduces its environmental impact, as individuals have to pay regardless of the effective automobile use. As we have seen, the main objective of environmental taxation is the internalization of externalities, through changes in the behaviour of the generator of the negative externality. Nevertheless, the aim of this tax is not related to the behaviour that we try to correct (the car use), but a very vague indicator of it (the vehicle ownership). The IVTM does not levy the emissions, but at most, the potential ability to produce them. Neither does the present tax design have an environmental content. The IVTM estimate directly the tax due, at the levels depicted in Table 4. As can be seen, the IVTM tax amount is calculated, in the case of passenger cars, depending on the tax horsepower. This variable is not directly related with engine power or with vehicle pollution ability. The formula of fiscal horsepower, in the case of the internal combustion engine, is the following: THP = C(0.785D2 S)0.6 N Table 4. IVTM tax levels in Spain. Power and type of vehicle A) Car passengers Less than eight tax horsepower From 8 to 11.99 tax horsepower From 12 to 15.99 tax horsepower From 16 to 19.99 tax horsepower From 20 tax horsepower on Tax due Euros 12.62 34.08 71.94 89.61 112.00 Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 1938 C.C. Williams et al. where THP is the tax horsepower, D the cylinder diameter, S the cylinder stroke, N the number of cylinders and C a constant, equalling 0.08 for four-stroke engines, and 0.11 for two-stroke engines. The relationship between cubic capacity and CO2 emissions is not a linear function for modern engines, as they could include devices such as a turbocharger or multi-valve engines that are used to increase power with the same engine cubic capacity. On the other hand, increasing the number of cylinders would raise the tax horsepower in a ratio of more than one unit per cylinder. One of the main problems with this calculation model is that it has an adverse effect for diesel against petrol engines, due to the increase in cubic capacity required to achieve the same power. And again the presence of discontinuities can have a serious impact on the THP amount, a slight increase in the tax horsepower could double the tax amount. From the previous calculations, town councils could apply a coefficient up to two. The implementation of this coefficient is discretionary, and does not necessitate any special requirement. This fact could imply very strong geographical divergences, leading to undesired fiscal competition. Lastly, town councils could introduce tax discounts, which in some cases could have some environmental impact (tax discount related to the fuel type, or engine characteristics). However, its implementation is very erratic, and the tax discounts usually have a temporary nature. Environmental proposals for the annual circulation tax The first important idea relating to this local tax is its limited role in fulfilling an important environmental function. Knowing this, there are some ideas that could improve the design of the IVTM. A good reform must take into account the following ideas: (1) Unnecessary exemptions must disappear; if we use the tax to emit a signal concerning the polluting behaviour of the owner, this signal must work in every case, including public sector vehicles, international organizations, etc. (2) The tax due must be calculated depending on the vehicle’s polluting ability. The variable that represents better the pollution is the CO2 emissions per kilometre. Linear tax rates depending on the vehicle emissions would be more simple and effective. And the present tax discontinuities should be avoided as they produce undesirable effects. (3) It is not recommended to maintain the coefficients that city councils can apply in a discretionary manner. In any case, we must keep in mind that the IVTM is not a tax on the vehicle use but on ownership, and this characteristic reduces the legitimacy of such types of coefficient. (4) Under this proposal, most tax discounts do not make sense. If the annual circulation tax is calculated depending on CO2 emissions, it makes no sense to use a tax discount for using environmental friendly fuel or engines. Fuel taxation Excise taxes on motor fuels are present in all European Union countries. In fact, the Council Directive 2003/96/CE (2003) established a minimum level of taxation, as shown in Figure 3. The level of the taxes is very different, and there are a number of transitory regimes to fulfil these minimum levels, especially for new entrants. With the exception of the UK, all countries apply lower tax levels on diesel than on petrol. But this difference, based in the taxation for commercial uses, is usually criticized. Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 The Service Industries Journal 1939 Figure 3. Excise duties in the European Union. Source: ACEA (2010). In Spain there are two taxes. On the one hand, the IEH levies the consumption of fuel in the manufacturing phase. The central government (42%) and autonomous regions (58%) share the tax collection. On the other hand, there is a regional tax, much smaller than the previous one, called IVMDH. It is introduced in the retail phase. The amount of these taxes depends on fuel consumption, so it works automatically discouraging emissions, acting as a disincentive to the use of the vehicle and to having a high consuming vehicle. Companies’ initiatives The governmental regulations we referred to above are part of the policy and legal factors that in addition to the sociological and cultural factors have ever more impact on forcing companies to consider the environmental effects, and leads the automotive industry to develop strategies that responds to these changes. The automotive companies try to innovate and be creative to cope with the new regulatory environment. They particularly focus on product design, trying to improve the current characteristics of the industry and make it more environment friendly, for example reducing carbon dioxide or NOX emissions. In a similar way, they innovate and look for different solutions which have led them to creating, designing and manufacturing hybrid vehicles combining the use of both fossil as well as electric energy, or give birth to entirely electric vehicles. To implement these strategies, a lot of companies have decided not to do so alone. There has been a lot of cooperation agreements, with suppliers (for production) and also with their competitors. For the latter, the main purpose that leads them to adopt these agreements is the high cost and risk that lies with innovation. As a matter of fact, the alliances have improved the innovation capacity as shown in a study by Vanhaverbeke, Gilsing, Beerkens and Duysters (2009). In a similar way, Inkpen (2005, 2008) has highlighted the knowledge transfer that occurs between General Motors and Toyota with NUMMI that can generate the proper climate for innovation. Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 1940 C.C. Williams et al. The cooperation between car manufacturer companies is becoming an ever more frequent strategy. The design of cooperation agreements between international companies was already experimented with during the 1980s (Hladik, 1988), giving way to more agreements during those years than ever before (Anderson, 1990). The increased rate in the number of agreements per year surpassed 20%, giving way to a concentration of agreements in three geographic areas, the USA, Europe and Japan (Hergert & Morris, 1988). Capowski (1994) pointed at alliances as the future for companies around the world, independently of their size or of the sector they belong to, and they become mandatory when competition increases. Halal (1992) refers to cooperation as the most powerful strength in the business world. The great notoriety of the alliances in the last few years is mostly due to the increase in competition that leads companies to use them as a way to improve their competitiveness, without losing their autonomy and flexibility, and to reduce considerably the investments in the required resources compared with other options. Preserving their flexibility is more adequate in situations of great variability of the demand or a strong uncertainty in their sector (Porter & Fuller, 1988). By increasing the uncertainty of their sector, it is also necessary to strengthen more powerful and sophisticated integration processes. The strategic alliances on a global scale for mutual help makes possible a major global efficiency in the achievement of the companies’ own goals (Halal, 1992). There are a lot of authors and several perspectives that explain the convenience of cooperation. Menguzzato (1992) summarizes those perspectives and groups them into three ‘logics’. First is the strategic logic: ‘it sets the cooperation as a strategic option oriented to improve the company’s competitiveness’ (Menguzzato, 1992, p. 55). In the same direction, Zineldin and Dodourova (2005) showed in their work that a strategic motivation is more important than any other type of motivation. In cooperation lies a strategic component because it affects the competitive position of the partners and it modifies the environment in which they are evolving (Collins & Doorley, 1992), even if it is just for a while. This is the reason why companies that are struggling in the marketplace have united their efforts in certain projects such as witnessed in Renault and Nissan in the making of cleaner cars, with less CO2 emissions reaching to the elaboration of electric cars. Something similar is happening with PSA Peugeot Citroën and Mitsubishi Motor Corporation and they are developing a strategic alliance to design and manufacture electric vehicles. The second logic is the economic logic, ‘This lies in the frame of the Transaction Cost Theory and justifies cooperation on the base of an economic efficiency criteria’ (Menguzzato, 1992, p. 55). And third and finally is the organizational logic, which justifies cooperation as a means of organizational learning (Menguzzato, 1992). In the case of the automotive industry, for most of these reasons, companies reach cooperation agreements. They maintain continuously such types of agreement with their suppliers, agreements that have been achieved from their very beginning and are becoming more and more common. As stated, this is for strategic reasons, and also to other reasons such as economic (it would cost them less, they could finance projects together), as well as organizational. Some automotive companies have gone a step further, however, signing off agreements with potential suppliers to their customers, as is the case for Renault and Nissan with Enel and Endesa, and with Acciona. The German car-makers, Audi, BMW, Daimler, Porsche and Volkswagen are working together to achieve a modular connection standard system for the refuel of the electric vehicles. On their side, Toyota, Nissan, Mitsubishi and Subaru have established an alliance with the Tokyo electric company, Terco. Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 The Service Industries Journal 1941 Conclusions Despite the successful reform of the IEDMT, its future is not clear at all. The Proposal for a Council Directive on passenger car-related taxes7 supports the total abolition of registration taxes over a 10-year transitional period. At the same time, the Council would reinforce the annual circulation taxes, including a CO2-based element. Nevertheless, this proposal seems to be frozen.8 From the point of view of economic regulation, this policy does not seem environmentally very appropriate. As this paper has shown in the case of Spain, but more widely applicable, automobile taxation rests upon three taxes: the fuel tax (Impuestos sobre Hidrocarburos), the annual circulation tax (IVTM) and the registration tax (IEDMT). The fuel tax and the registration tax could play an important environmental role, but it is not so easy for the annual circulation tax to fulfil such a function. The fuel tax implies a cost related to vehicle use. The registration tax is a signal concerning the acquisition of the ‘polluting machine’. In the present design, the IEDMT discourages the acquisition of more polluting engines, and rewards through a tax exemption, the acquisition of cleaner vehicles. In fact, this tax could be improved to raise its environmental influence, reinforcing the consumer tendency to buy cleaner vehicles. Nevertheless, the circulation tax does not include any of the above-mentioned incentives. It is a tax charged annually that could be designed taking into account the potential emissions of the automobile. But it will never affect two of the major aspects that are related to pollution. These are firstly, the purchase of a more or less efficient vehicle, as this tax is charged yearly and the car has been already bought when the owner has to pay it, and secondly, the behaviour of motorists; tax will be charged regardless of the way people use their cars. In any case, the present IVTM needs an urgent reform that ensures that this tax takes more fully into consideration the environmental effects. The environmental demands and the public regulation proposals have caused the carmanufacturing companies to react. They have developed agreements between one another, as well as with their suppliers, and also with future suppliers to consumers, that is, with electric companies. In sum, this paper has evaluated the various innovative initiatives being used to make the car industry more environmentally friendly, particularly in relation to the Spanish context. If this paper thus encourages further research on identifying the most appropriate ways forward, then it will have fulfilled its objective. If it also causes governments and motor manufacturers to pause for a moment of reflection on the policies they pursue, then it will have fulfilled its wider objective. Notes 1. European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) (2010). 2. There is a detailed study of this tax and its reform in Fuenmayor (2009, November). 3. The PREVER plan was a public subsidy canalized though a tax credit awarded on the acquisition of a new passenger car, if the owner destroyed an old, used car. This plan disappeared in 2008. 4. European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) (2010). 5. A deep analysis of this tax can be found in Fuenmayor (2010, September). 6. There are some exemptions: official vehicles used in national defense or citizen security, cars owned by international organizations; vehicles used in medical care or owned by handicapped people; vehicles used in public transportation, etc. 7. European Commission (2005). 8. There are several question to the European Parliament related with progress in this proposal (E-1940/2008, E-4512/2010). The answers show the difficulties to reach an agreement. 1942 C.C. Williams et al. Downloaded by [University of Sheffield] at 03:15 16 August 2011 References Anderson, E. (1990). Two firms, one frontier: On assessing joint venture performance. Sloan Management Review, 32, 19–30. Capowski, G. (1994). El arte de las alianzas: Entrevista con Jordan D. Lewis. Harvard Business Review, 64, 40–43. Collins, T.M., & Doorley, T.L. (1992). Les alliances strategiques. Parı́s: Intereditions. Council Directive 2003/96/CE. (2003, October 27). Restructuring the Community framework for the taxation of energy products and electricity. Official Journal of the European Union, L 283, 31/ 10/2003, 0051-0070. European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA). (2010). ACEA tax guide 2010. Brussels: Author. European Commission. (2002). Taxation of passenger cars in the European Union. Brussels: Author. European Commission. (2005). Proposal for a council directive on passenger car related taxes. Brussels: Author. Faconauto. (2008, June 11). Las ventas de vehı́culos más contaminantes se desploman un 44% con el nuevo impuesto verde. Boletı́n Faconauto. Fuenmayor, A. (2009, November). El Impuesto Especial sobre Determinados Medios de Transporte: ¿puede ser un impuesto ambiental? Paper presente at the II Congreso International de Prevención de Riesgos en los Comportamientos Viales, Valencia. Fuenmayor, A. (2010, September). El Impuesto sobre Vehı́culos de Tracción Mecánica. Algunas propuestas para una reforma ambiental. Paper presented at the VI Jornada de la Oficina de Defensa del Contribuyente, Madrid. Halal, W.E. (1992). La dirección estratégica en un nuevo orden mundial. Harvard Business Review, 66, 6–12. Hergert, M., & Morris, D. (1988). Trends in international collaborative agreements. In F.J. Contractor & P. Lorange (Eds.), Cooperative strategies in international business (pp. 99–109). New York, NY: Lexington Books. Hladik, K.J. (1988). R&D and international joint ventures. In F.J. Contractor & P. Lorange (Eds.), Cooperative strategies in international business (pp. 188–203). New York, NY: Lexington Books. Inkpen, A.C. (2005). Learning through alliances: General Motors and NUMMI. California Management Review, 47, 114–138. Inkpen, A.C. (2008). Knowledge transfer and international joint ventures: The case of NUMMI and General Motors. Strategic Management Journal, 29, 447–453. Menguzzato, M. (1992). La cooperación: Una alternativa para la empresa de los 90. Revista de Dirección y Organización, 4, 54–62. Porter, M.E., & Fuller, M.B. (1988). Coaliciones y estrategia Global. Información Comercial Española, 658, 101–120. Vanhaverbeke, W., Gilsing, V., Beerkens, B., & Duysters, G. (2009). The role of alliance network redundancy in the creation of core and non-core technologies. The Journal of Management Studies, 46, 215–243. Zineldin, M., & Dodourova, M. (2005). Motivation, achievements and failure of strategic alliances: The case of Swedish auto-manufacturers in Russia. European Business Review, 17, 460–471. View publication stats