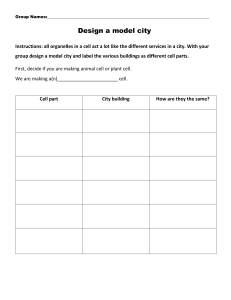

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362741366 Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings Article in International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation · August 2022 DOI: 10.1108/IJBPA-12-2021-0166 CITATIONS READS 0 795 3 authors, including: Khor Soo Cheen Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman 19 PUBLICATIONS 14 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Khor Soo Cheen on 19 September 2022. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2398-4708.htm Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings Christtestimony Jesumoroti, AbdulLateef Olanrewaju and Soo Cheen Khor Department of Construction Management, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kampar, Malaysia Abstract Purpose – Hospital building maintenance management constitutes a pertinent issue of global concern for all healthcare stakeholders. In Malaysia, the maintenance management of hospital buildings is instrumental to the Government’s goal of providing efficient healthcare services to the Government’s citizenry. However, there is a paucity of studies that have comprehensively explored all dimensions of hospital building defects in relation to maintenance management. Consequently, this study seeks to evaluate the defects of hospital buildings in Malaysia with the aim of proffering viable solutions for the rectification and prevention of the issue. Design/methodology/approach – The study utilised a quantitative approach for data collection. Findings – The findings indicated that cracked floors, floor tile failures, wall tiles failure, blocked water closets, and damaged windows were some of the flaws that degrade hospital buildings. The study’s outcomes reveal that defects not only deface the aesthetic appearance of hospital buildings but also inhibit the functionality of the buildings and depreciate the overall satisfaction. Research limitations/implications – Considering the indispensable role of hospital buildings in the grand scheme of healthcare service provision and ensuring the well-being of people, the issue of defects necessitates an urgent re-evaluation of the maintenance management practices of hospital buildings in Malaysia. Previous studies on the maintenance management of hospital buildings in Malaysia have focused primarily on design, safety, and construction. Practical implications – This is particularly important because defects in hospital buildings across the country have recently led to incessant ceiling collapses, fire outbreaks, ceiling, roof collapses, and other structural failures. These problems are typically the result of poor maintenance management, exacerbated by poor design and construction. These disasters pose significant risks to the lives of hospital building users. Originality/value – This study offers invaluable insights for maintenance organisations and maintenance department staff who are genuinely interested in improving hospital buildings’ maintenance management to optimise staff’s performance and enhance the user satisfaction of hospital buildings in Malaysia and globally. Keywords Amenities, Critical success factors, Implementation, Requirements, Structural failure, Services Paper type Research paper Received 15 December 2021 Revised 17 February 2022 8 April 2022 26 April 2022 Accepted 27 April 2022 1. Introduction Hospital buildings are confined spaces that serve the specific purpose of ensuring the health and wellness of people with highly sophisticated facilities used for treatment; this characteristic distinguishes them from other types of buildings (Garip, 2011). Hospital buildings provide a serene and enabling environment that facilitates the efficient delivery of medical services and patients’ social connections (Amos et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). This condition is critical because the state of a building has a significant impact on the health of the occupants and the environment (Abd Rani et al., 2015). This makes the maintenance management of hospital buildings one of the most complicated tasks in the field of maintenance, as hospital buildings are complex, highly functional, costly, and cumbersome to maintain and manage (Fore and Msipha, 2010; Muchiri et al., 2011; Maletic et al., 2012; Macchi and Fumagalli, 2013). The research has been carried out under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme Project (No: FRGS/1/ 2018/TK06/UTAR/02/5) provided by the Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia. The authors are grateful for the grant. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation © Emerald Publishing Limited 2398-4708 DOI 10.1108/IJBPA-12-2021-0166 IJBPA Hospital building defects have a significant negative impact on the value of services and best practices of the healthcare sector. Not only do defects in hospital buildings contribute to structural deterioration and component depreciation, but they also significantly inhibit the performance of hospitals (Adam and Abu Bakar, 2021). In a similar vein, the maintenance of hospital buildings has remarkable effects on the functionality of the facilities and users’ satisfaction. Maintenance management is necessary to ensure the quality performances of buildings and preserve their life span. However, it is a complex process that could be highly exorbitant if not cleverly conducted to minimise cost. The maintenance of hospital buildings must be conducted appropriately to maximise their functionality (Abd Rani et al., 2015). This process necessitates regular extensive routine maintenance to ensure the smooth running of healthcare facilities and their unhampered provision of essential services (Olanrewaju et al., 2018). To achieve best practices, critical success factors must be initiated to enhance both positive planned and unplanned maintenance management for hospital buildings to determine the defects and improve their services. Therefore, it is pertinent to implement efficient maintenance management protocols in order to preempt and ameliorate the occurrence of defects in hospital buildings in Malaysia. To accomplish outstanding maintenance, it is crucial to have a maintenance management strategy that conforms to the expected requirements of users (Nik-Mat et al., 2011). Hence, strategic maintenance is instrumental to hospital buildings’ productivity and user satisfaction. Undermining hospital building maintenance management can have catastrophic consequences, as evidenced by recent media and research reports of increased ceiling and roof collapses, fire outbreaks, and structural decay in Malaysian hospital buildings (Tan, 2018; Olanrewaju et al., 2019; FMT reporter, 2019; Su-Lyn, 2020a,b). These adverse outcomes help explain why Wood (2005) dubbed building maintenance the “Cinderella” activity of the construction industry because it has historically been a neglected and abandoned technology field. Interestingly, there has been viral news about some instructions articulated through official government circulars (2003–2010; 1995; 1991 and 2003) in Malaysia that suggest that the Government is taking the issue of building maintenance (BM) more seriously (cited by Mohd-Noor et al., 2011). 2.1 Maintenance Maintenance encompasses the technical and administrative actions required to preserve a building in an optimal state, one in which it efficiently serves its purposes (Hashim et al., 2019; Townsend et al., 2017). The process also entails protecting, repairing, monitoring, and improving buildings to ensure maximum performance. It can also be described as the precautionary measures undertaken to reduce the adverse effects of defects and maximise the efficacy of the facility at minimum cost (L€ofsten, 2018). The foremost goal of building maintenance is to protect and preserve a building in its unique state to serve its purpose efficiently (Enshassi et al., 2015). In conjunction with effective management, maintenance preserves and improves the quality of buildings; the practical application of both practices produces incredible outcomes. Building maintenance is caused by various factors, as contained in Table 1 (Ogunmakinde et al., 2013; Ofori et al., 2015). To effectively curb the incidence of defects in buildings, it is crucial to understand the causes and agents of building deterioration. 2.2 Defects The term “defect” in the construction industry refers to inadequacies in the planning, design, and construction processes and other external factors such as wear and tear. Construction and design defects are caused mainly by inefficient craftsmanship, inadequate construction Common factors deterioration Design deficiencies Agents of deterioration Ageing Stock of Building Obsolescence Shape and form Materials selection Biological Mechanical Agent Advent of New Technologies Design Approach Weathering a. Moisture b. Wind c. Atmospheric Gases Rising Social Expectation and Design Chemical Aspiration Maintainability a. Sulphate attack b. Salt Source(s): Ofori et al. (2015) and Ogunmakinde et al. (2013). Ageing stock of building factors Control of material Change of use of Building Vandalism Control of work on site Lack of maintenance Lack of use of Building Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings Table 1. Causes and agents of building deterioration methods, and substandard building materials (Olanrewaju et al., 2010). Defects in a building accelerate its depreciation and shorten its lifespan. As previously mentioned, building defects mar the expected performance of buildings, user satisfaction, the expected quality of services, and other amenities. Defects in buildings can be either obvious or hidden (Othman et al., 2015). The frequency of building defects is shown in Table 2, based on reported cases of building defects in Malaysian hospital buildings from 2006 to 2017. According to Gurmu et al. (2020), the frequency of structural defects in buildings directly influences the subsequent reconstruction and maintenance costs, the time required to correct the defects, the degree of user contentment, and the reputation of the service industry. In this regard, researchers argue that to effectively classify the most prevalent root causes of building defects, it is vital to conduct investigations regarding the rudiments and history of the buildings (Lee et al., 2019; Gurmu et al., 2020) Although there have been extensive efforts to classify and eradicate the leading causes of construction defects, it is essential to note that defects do not always occur due to a singular cause. Instead, some defects occur due to closely related causes (Aljassmi and Han, 2013). As a result, this study seeks to proffer solutions to the challenging problem of defects in hospital buildings in Malaysia by exploring the parameters that have not been fully addressed. Some primary factors that cause damage to buildings include the construction of buildings on spread-out Earth, the proximity of gardens to buildings, poor drainage systems, climatic changes, improper foundation designs, and damaged water pipes (Gurmu et al., 2020; Zumrawi et al., 2017). The most prevalent causes of hospital building defects include the following: Faulty electrical systems: lack of energy, power failure, defective electrical Defects of hospital buildings in Malaysia Ceiling collapse Dampness Malfunction of facilities Fire accident Wall crack Water closets facilities failure Inappropriate materials and design Piping system failure Heating, ventilating, air conditioning system failure Source(s): Tan (2018) Years (2006–2017) Number of defects 7 5 6 13 8 5 5 8 6 Table 2. Reported cases of hospital building defects between 2006 and 2017 in Malaysia IJBPA installations, problematic lamps, and light fixtures/sockets/circuit breakers/switches/wiring; mold and fungi: the growth of fungi is ordinarily the consequence of excessive dampness— fungi blossoms under favourable conditions with enough moisture and nutrients (Dahal and Dahal, 2020); timber deterioration; poor design; poor construction; termite infestation; dampness and excessive moisture: approximately 71% of the hospital buildings had issues with dampness. The most common issues include rising dampness, leakages on services, and penetrating dampness. Dampness can occur from unintentional water caused by leaky pipes, flashings, and gutters, which cause defects such as cracks in the concrete walls, leaking pipes, and concrete wall dampness (Gurmu et al., 2020; Abdul-Rahman et al., 2014). Water from the leak frequently permeates the wall, resulting in horrifying water tints (Elhag and Boussabaine, 1999). The permeation of such dampness, combined with inadequate ventilation within the building, promotes the excessive growth of fungi and algae on the wall surfaces (Dahal and Dahal, 2020). Table 3 below highlights some of the preceding building defects reported in Malaysia’s hospital buildings. Moreover, since the inadequacy and lack of compliance of standard operational procedures for hospital maintenance management, and as such, from a survey conducted for doctors, medical officers, nurses from government and clinics rated hospital maintenance management as poor from codeblue reports, march 2020, over 60% are poor maintenance practices and procedures and this caused leaky ceilings, collapsing of ceiling, fire outbreak, structural failure, wall cracked and complaints (Su-Lyn, 2020a, b). See below overall reports from codeblue as reported and FMT Reporters: 337 Survey conducted among doctors from government hospital 38% of doctors rate the overall maintenance of their public health facility as poor or terrible Year Year 2007 Year 2010 Year 2011 Year 2012 Year 2013 Year 2014 Year 2015 Year 2015 Year 2016 Year 2016 Year 2016 Year 2016 Year 2016 Year 2016 Table 3. Hospital buildings reported cases and complaints Reported cases Electrical trapping in elevator in Neurology Ward, Kuala Lumpur Hospital Fire accident in Tengku Ampuan Rahimah Hospital, Klang Ceiling collapse in Serdang Hospital, Kuala Lumpur Ceiling collapse in Serdang Hospital, Kuala Lumpur Ceiling collapse in Serdang Hospital, Kuala Lumpur Fire accident in Sarawak General Hospital, Kuching Fire accident in Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah, Klang Wall cracks in Tampin Hospital, Negeri Sembilan Fire accident in KPJ Sabah Specialist Hospital Lift malfunction in Sultanah Aminah Hospital, Johor Bahru Fire accident in Sri Kota Specialist Medical Centre, Klang Ceiling collapse in Tengku Ampuan Afzan Hospital, Kuantan Fire accident in Sultanah Aminah Hospital, Johor Bahru Heating, Ventilating and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) System failure in Hospital Tengku Ampuan Afzan, Kuantan Year 2016 Lift malfunction in Sarawak General Hospital Year 2017 Fire accident in Hospital Bahagia Ulu Kinta, Perak Year 2017 Electrical short circuit in Shah Alam Hospital Year 2016 Electric short circuit in Hospital (RPB) Year 2017 Electrical short circuit in Tanjong Karang Hospital, Shah Alam Year 2017 Ceiling collapse in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang Year 2019 Leaky roofs, ceiling, power cut, water cut in Petaling Jaya Source(s): Tan (2018); FMT reporter (2019); Su-Lyn (2020a,b) 51 reported electricity supply interruption at medical facilities at least once in a year 10% complaining of monthly power cuts 10% claiming water cuts 60% of the problems was reported in public health facilities were related to old and failing equipment such as tools or anesthetic machines and also infrastructural issues like cracked walls broken lights or ceiling collapsing 80% survey of said their issues remained unresolved even after two years of filing their complaints 44% overall maintenance survey from respondents gave fair rating 18% rated the condition of their facility good or excellent 2.3 Hospital building users Hospital buildings differ from other buildings because they accommodate a diverse clientele of users. These individuals include medical personnel such as physicians, nurses, psychologists, dentists, veterinarians, patients, and other non-medical staff and visitors. Moreover, hospital buildings provide healthcare services and treatment to the general public, with a variety of medical amenities and utility rooms equipped with various medical equipment. Thus, it is critical to consider the input of professional specialists and medical physicians familiar with specialised amenities and medical equipment. Therefore, when hospital buildings are designed, the design must be done by professionals who consult with various authorities to ensure the function of each room is well understood (Chan et al., 2003). Over the years, hospital buildings across Malaysia have experienced mishaps such as fire outbreaks and ceiling collapses due to the decay in hospital buildings. These mishaps constitute a severe safety and wellness concern for healthcare stakeholders and necessitate urgent critical research to investigate the maintenance management practices of hospital buildings in Malaysia (Olanrewaju et al., 2018). Given that we live in an ever-changing environment riddled with uncertainty, there is an urgent need to reassess hospital building maintenance planning and comprehensive maintenance techniques (Lind and Muyingo, 2012). Recent studies have shown that the maintenance sector in Malaysia is critically unstable, with increasing incidences of maintenance failures and building defects. This situation underlines the ineffectiveness of Malaysia’s building maintenance systems (Zawawi et al., 2011), which is partly attributable to the insufficient allocation of time and resources to bolster the functionality of the operational and maintenance activities of building maintenance management (Ali et al., 2010; Olanrewaju et al., 2010). Similarly, recent Jordanian studies identified ineffective maintenance management practices as the primary factor affecting hospital building maintenance performance (Jandali and Sweis, 2018; Jandali et al., 2018). According to Abd Rani et al. (2015), factors affecting hospital performance include the building’s age, its surroundings, the availability of managerial resources, the building’s actual occupancy, and the labour sources used to perform maintenance work (either in-house or outsourced). They argue that numerous organisations fail at maintenance management because of poor management planning (Abd Rani et al., 2015). Hospital building designs and construction can also adversely affect the maintenance of buildings, especially if the design is complex. Therefore, it is imperative to carefully consider the future repercussions of the approaches, resources (human and material), and the financial implications of maintenance management processes during the design stage of hospital and facility building (Sanchez-Barroso and Garcıa-Sanz-Calcedo, 2019; Gomez-Chaparro et al., 2020). Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings IJBPA 2. Literature review The relevance of healthcare buildings lies in the fact that they serve a wide range of purposes such as caregiving, treatment of health issues, as well as recuperation and rehabilitation procedures (Lavy et al., 2014) (Evans and Etienneb, 2010). These activities suggest that healthcare buildings are constantly in use and require regular maintenance management and frequent modification (Enshassi et al., 2015). As a result, flexibility and adaptability are indispensable features required to support the wide range of activities within these healthcare facilities, including medical building maintenance management (Olanrewaju et al., 2019). Building maintenance management entails several components, including determining maintenance task intervals, selecting maintenance strategies, and risk assessment; it also consists of a building maintenance policy. This written document serves as a management guide for the maintenance staff in establishing appropriate standards and strategies (Jesumoroti and Cheen, 2021). Also, there are some rudiments to this: provision of maintenance resources, defining maintenance standards, and choosing a maintenance strategy to design maintenance policy. Maintenance strategy involves condition-based, preventive and corrective maintenance (Chyu et al., 2015). For instance, public buildings in Penang, Malaysia, were evaluated. Issues such as the absence of quality building maintenance standards, non-availability of replacement parts and components, lack of responsiveness to maintenance requests, inadequate preventive maintenance, and insufficient maintenance funds were identified as the major causes of the poor maintenance management reported by building maintenance organisations (Jandali et al., 2018). In Israel, a study that evaluated the performance of community clinics and hospital facilities based on their maintenance culture revealed the urgent need for adequate financial measures in building maintenance to improve the quality of service provided by healthcare facilities (Shohet and Lavy, 2017). Hospital building maintenance safeguards the structures and ensures that they remain in an optimal state of safety and functionality in line with established standards. As previous research has demonstrated, the maintenance practices used by hospitals have a significant impact on the performance of hospital buildings and thus define the maintenance management tactics used by other hospitals (Osunsanmi et al., 2020; Razak and Jaafar, 2012). The maintenance of buildings and their environs, or the lack thereof, remarkably affects the performance of hospital buildings and the entire country. Hospital buildings must be adequately maintained to maintain an optimal level of functionality and performance (Hayat and Amaratunga, 2014; Lind and Muyingo, 2012; Vandesande and Van Balen, 2016). Building defects have an adverse effect on users’ satisfaction, productivity, and maintenance costs. A building defect can cause concerns to its occupants. Additionally, it may result in the delay of a patient’s recovery process. Defects must be handled effectively and efficiently to ensure optimal building performance and user satisfaction. Defect management is a strategic part of maintenance management and one of the primary functions of the maintenance organisation (Olanrewaju et al., 2022b). Building defects can manifest themselves in the structure, fabric, services, and other amenities of the faulty structure. Defects include cracked, broken, or degraded brick/block walls, clogged water closets, and malfunctioning lifts. Leaking showers and faulty windows and doors are also examples of defects. Defects are transmittable because, if not addressed promptly, they can cause havoc on adjacent components, elements, or building pieces (Olanrewaju et al., 2022a). Any individual, group, or organisation that uses the hospital building as an occupier, owner, renter, or visitor is considered a stakeholder. According to Olanrewaju and Tan (2022), users must evaluate a building’s performance and service delivery in order to continue justifying investment or uptake in building maintenance. This type of evaluation is critical because building defects impair the functionality and delivery of services. In addition, building defects affect the occupants’/clients’ satisfaction and can result in disputes and litigation between clients/users, developers, and maintenance companies (Lee et al., 2018; Jonsson and Gunnelin, 2019; Olanrewaju and Lee, 2022a,b). The effect of defects on buildings’ condition, appearance, and performance is determined by the buildings’ functional requirements (Olanrewaju et al., 2021). Additionally, a malfunctioning element, component, or section of a building affects the building’s users’ safety, comfort, convenience, and health (Faqih and Zayed, 2021). However, certain factors, such as critical success factors, contribute to hospital building defects. The critical success factors (CSFs) refer to the fundamental factors required to ensure that a project attains its expected functions and meets stakeholders’ requirements. CSFs analysis enables the identification of the essential aspects of a project, which are of considerable interest to stakeholders toward the achievement of the project’s goal (Olanrewaju et al., 2019). Muhammad and Johar (2019) rightly contend that there is a poor understanding of the critical success factors for buildings in developing countries like Malaysia. Additionally, Kuwaiti et al. (2018) noted that there are thirty-six critical success factors for establishing healthcare projects in the United Arab Emirate (UAE), which are listed in Table 4. From a maintenance perspective, critical success factors encompass the diverse maintenance processes and activities, as well as the decisions taken at each step of the maintenance service delivery. These factors are instrumental to both strategic and tactical decision making. Some of the factors are common and obvious, while others are ambiguous. The most prevalent factors affecting building maintenance include an inadequate budgetary allocation for maintenance and operation (Lam et al., 2010); idle properties (Bambang, 2006); low maintenance operation of assets; and insufficient skilled human capacity (Adamy and Abu Bakar, 2021). While financial constraints primarily impede building maintenance, the issue is not always financial in nature. Existing research outside Malaysia has addressed the critical performance indicators for the maintenance of hospital buildings. For instance, Olanrewaju et al. (2019) identified the following performance indicators: building performance indicators, workforce source diagrams, maintenance efficiency indicators and managerial span of control, business availability, urgent repair request indexes, manpower utilisation indexes, preventive maintenance ratios, average time for repairs and maintenance productivity, and soft indicators. However, key performance indicators (KPIs) differ from the CSFs. For example, critical success factors refer to the processes of decision making to produce predetermined results, while key performance indicators are used to measure results. Similarly, critical success factors could be likened to quality assurance, whereas key performance indicators pertain more to quality control (Olanrewaju et al., 2018). 2.1 Theoretical and Conceptual framework The framework outlined below was developed and used throughout this study as a guide. This framework is critical to ensuring that the research study’s goals and objectives are met. Consequently, the primary research adopted a mixed method for data collection, analysis, and interpretation, as illustrated in Figure 1, in order to address ontological, epistemological, and methodological issues related to conceptualising and theorising building maintenance management. This process took cognisance of maintenance users’ needs and building performance in decision-making, which was done systemically, representing the process, activities, and stakeholders’ value systems in hospital building maintenance. Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings IJBPA Critical success factors References Top management support Dezdar and Ainin (2012), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Dezdar and Ainin (2012), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Pinto and Slevin (1988a), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Abdul-Aziz and Kassim (2011), Meng et al. (2011), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) PMI (2004), Dezdar and Ainin (2012) Al-Mudimigh (2007), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Bourne and Walker (2008), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Nguyen and Ogunlana (2004), Dezdar and Ainin (2012), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Hong (2009), Al-Turki (2011), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Al-Shamlan and Al-Mudimigh (2011), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Meng et al. (2011), Osei-Kyei and Chan (2015) Jamali (2004), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Tang et al. (2013) Pinto and Slevin (1988a), Nguyen and Ogunlana (2004) Abdul-Aziz and Kassim (2011), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Meng et al. (2011), Ng et al. (2012) Pinto and Slevin (1988a), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Nguyen and Ogunlana (2004), Kamal (2006), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Nguyen and Ogunlana (2004), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Nguyen and Ogunlana (2004), Ralf (2012) Jacobson and Choi (2008), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Li et al. (2005), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Al-Saadi and Abdou (2016) Abdul-Aziz and Kassim (2011), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), AlSaadi and Abdou (2016) Dezdar and Ainin (2012), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Dezdar and Ainin (2012), Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Almajed and Mayhew (2013) Mandal and Gunasekaran (2003), Finney and Corbett (2007) Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Commitment to project Project mission Monitoring and feedback Project management Process management Stakeholder management and involvement Clear information and communication channels Effective strategic planning Change readiness Long-term demand of the project Transparent procurement Systematic control mechanisms Competitive procurement Technical tasks Troubleshooting Adequate funding throughout the project Availability of resources Accurate initial cost estimates Community involvement/support Stable economy Political stability Competent project manager Multidisciplinary/competent project team Training and education Implementing an effective safety program Implementing an effective quality assurance program Appropriate risk allocation and sharing Client acceptance/satisfaction Client consultation Public/community acceptance Technology innovation Table 4. Critical success factors for establishing healthcare projects Environmental impact of the project Social needs considerations Troubleshooting Source: Kuwaiti et al. (2018) Pinto and Slevin (1988b), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Kemppainen et al. (2012), Almajed and Mayhew (2013), Al-Saadi and Abdou (2016) Pinto and Slevin (1988b) Pinto and Slevin (1988b) Li et al. (2005), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Yong and Mustaffa (2012), Ng et al. (2012), Al-Saadi and Abdou (2016) Tiong (1992), Jefferies et al. (2002) Murphy et al. (1974), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Pinto and Slevin (1988a), Yong and Mustaffa (2012) Ontology: Posivism Epistemology Methodology: Objecvism Explanatory Subjecvism Exploratory Technique: Observaon, Survey, case studies, interview Source(s): (Olanrewaju et al., 2019) 3. Methodology Data for this study were collected using a structured closed-ended questionnaire. This approach was adopted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which precluded direct contact with respondents, many of whom were extremely busy frontline workers. The survey was also completed using a quantitative online survey approach. The data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 25 (SPSS). The quantitative method was adopted because of the need to obtain quick and precise responses to questionnaires. This study forms part of broader ongoing research to continuously improve hospital buildings maintenance management in the Malaysian construction industry. To this end, an extensive review of relevant literature on hospital buildings maintenance management in Malaysia and globally was undertaken. Primary data was gathered through snowball sampling for online survey questionnaires due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling technique employed when information about possible responders is limited. The technique is an inductive one. It involves distributing the survey to as many accessible and willing respondents as possible (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). One of this technique’s drawbacks is that the researcher will have no idea how many people responded. Nevertheless, while the findings may not be generalisable, they can be representative when there are a significant number of respondents (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). The respondents for the study comprised medical professionals such as nurses, physicians, psychologists, dentists, veterinarians, other healthcare providers, and maintenance management professionals, including mechanical engineers, civil engineers, and builders. For different segments, the questionnaire survey used a four-point scale, a fivepoint scale, and a six-point scale. For the question “How frequently do building defects occur? ” respondents’ perceptions were elicited using a 4 Likert scale: 1 5 Not Often, 2 5 Often, 3 5 Very Often, and 4 5 Extremely Often. Respondents’ perceptions of the overall building performance were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale: 1 5 Least Satisfied, 2 5 Less Satisfied, 3 5 Satisfied, 4 5 Very Satisfied, and 5 5 Extremely Satisfied, while respondents also rated the nature of the defect resolution in the buildings on a 6-point scale: 1 5 Least Critical, 2 5 Least Common, 3 5 Less Common, 4 5 Common, 5 5 Very Common, and 6 5 Extremely Common. This study focuses on the perspectives of various stakeholders on maintenance management and the perspectives of staff members responsible for maintenance management in hospital facilities. Perak, Penang, Kedah, Pahang, Malacca, Selangor, Sarawak, Sabah, Kelantan, Terengganu, Perlis, Negeri Sembilan, Seremban, and Johor states, in which Selangor has the highest number of hospitals 25.93%, followed by Kuala Lumpur, Johor, Pulau Pinang and Perak all together making 76.39 in Peninsular Malaysia have the Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings Figure 1. Theoretical and conceptual framework IJBPA higher number of hospital structures. The estimation process for determining sampling size provides a reliable number of audiences to be targeted. When distributing the questionnaires, this study used a “Snowball sampling” (non-probability sampling approach) as well as a “Simple Random Sampling” (where the odds are the same for any given participant being chosen) to gather more replies owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. The questionnaire was generated through an extensive literature review to address the research problems in view of achieving the aim of this study. The questionnaire was constructed for the users of the hospital buildings or people working in the hospital, such as nurses, physicians, psychologists, dentists, veterinarians, and other healthcare providers, as well as maintenance management professionals, including mechanical engineers, civil engineers, and builders. About 14 hospitals responded to the questionnaire from 14 respondents and analysed. The questionnaire was validated and tested with SPSS to ascertain its reliability, and it was reliable. The tests utilised were t-test, reliability, validity, mode, and standard deviation. The Bartlett test was performed to increase the equipment’s accuracy. The sample mean’s standard error measures how close the sample mean is to the population mean. The data collection instrument’s validity and reliability are critical for collecting accurate data. A questionnaire must possess two critical characteristics: reliability and validity, to be considered acceptable. The former assesses the questionnaire’s consistency, while the latter assesses the degree to which the questionnaire’s results correspond to reality. A lower standard error indicates that the sample mean is a more accurate representation of the population mean. SPSS analysed the study’s data and performed T-tests with all their associated statistics. The study validates its findings using Spearman’s correlation; correlation quantifies the strength of a linear relationship between two variables. Correlation is statistically significant at the 0.01 level. P 5 1–6£ d2/n (n2-1), where p is Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, D1 is the difference between each observation’s two ranks, and N is the number of observations. 3.1 Result and analyses All of the constructs were expressed in a good manner. The survey was adequate for the research. The following tests were used: t-test, reliability, validity, mode, and standard deviation. The Bartlett test was used to improve the accuracy of the equipment. The one-way ttest showed that cracked floor, floor tile failure, wall tile failure, blocked water closet, damaged window, damaged ceiling, damaged door locks, faulty shower, faulty fans and others are top defects in the hospital building. The standard error of the sample mean measures how near the sample mean to the population mean. A lower standard error indicates that the sample mean represents the population mean more accurately. A total of 32 faults were discovered and reported by building users, affecting buildings and engineering services. The survey was conducted over eight months, from March 2019 to January 2020. As shown in Table 5, the composition of respondents reveals that they had educational backgrounds in engineering and the environmental sciences. Mechanical engineering is ranked first in terms of respondents, followed by civil engineering, biomedical science, nurses, and other medical professionals. According to these findings, hospitals employ both management and engineering professionals, such as engineers and facility managers, because they require the necessary professional skills and knowledge of management strategies and budget planning. Additionally, Table 5 illustrates the various ages of the buildings. It reveals that 4 buildings were less than 10 years old, and 6 were between 20 and 30 years old. Others include 1 building between 30 and 40 years old and another building that was more than fifty years old. This information implies that regardless of the age of the hospital buildings, they must be maintained in a good state of repair, including the older structures. The categorisation of hospital buildings revealed that most respondents worked in private establishments, with 8 Nursing Civil Biomedical Science Others Total Total 4 4 4 1 13 Professional background F 28.6 28.6 28.6 7.1 92.9 % Less than 10 years 20–30 years 30–40 years More than 50 years Total Age of the building 4 6 1 1 12 F 33.36 50.0 8.3 8.3 99.9 % Public Hospital Private Hospital 61.5 38.5 100 13 % 8 5 Classification of hospital F Nurse Engineer Facilities Manager Medical Doctor Medical Laboratory 5 5 1 1 1 13 Position in the department F 38.5 38.5 7.7 7.7 7.7 100 % Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings Table 5. Respondents’ background and hospital building characteristics IJBPA working in private hospitals and 5 in public hospitals. A closer examination of Table 5 reveals that the respondents included 5 nurses, 5 engineers, 1 medical doctor, 1 mechanical engineer, 1 facility manager, and 1 medical laboratory technician. This uneven distribution of specialised professionals suggests the critical need for additional professionals in various departments. 4. Discussion The location of the hospital buildings is shown in Table 5; they were from six states. Additionally, it reveals the respondents’ educational background. All respondents were educated, holding either an undergraduate or postgraduate degree. This observation proves that one needs to have a relatively high educational qualification and requisite knowledge to work as a hospital engineer or facility manager. Two of the thirteen respondents had a postgraduate degree, while nine had an undergraduate degree. Table 6 illustrates the number of years the respondents had worked in their hospitals; 10 have less than 5 years of experience, while 3 have between 11 and 15 years of experience. According to the survey’s descriptive data, more than 40% of customers reported experiencing problems but remaining overly satisfied or extremely delighted with the building’s components. Although 60% believe that defects do not occur frequently, 15% believe that defects do arise with building maintenance management. The reliability and validity of the pooled data were 0.505 and 0.575, respectively. These findings corroborated the one-sample t-test results, indicating that all structural problems were present. This was sufficient because a value less than 0.000001 implies multicollinearity and Hinton (2014) affirmed this as well. According to this study, the most frequently occurring errors in hospital buildings are multidimensional. The commonalities were all greater than 0.5, indicating that the faults showed several common variants. Additionally, the frequency of various flaws in construction components is given in Table 6. Not frequently occurs at 3, very frequently occurs at 2, frequently occurs at 7, and quite frequently occurs at 1. The findings indicate that the average respondent confirmed that faults frequently occur in their properties. Similarly, the performance and user satisfaction ratings of the buildings shown in Table 6 indicate the following: 3 are least satisfied, 7 are less satisfied, 2 are satisfied, and 1 is extremely satisfied. This result suggests that the average respondent believes their building’s performance and overall user satisfaction are below the desired expectation. Thus, the study argues that a comprehensive approach should be taken to the maintenance practices and management of hospital buildings to optimise their performance and functionality while also exceeding users’ expectations and overall satisfaction. Table 6. Respondents’ professional characteristics and perception on buildings’ performance Defects occur in the building F % Not often 3 21.4 Bachelor 8 57.1 Very often 2 14.3 Master 2 14.3 Often Extremely often 7 1 50 7.1 Diploma 3 21.4 7.1 1 13 14 7.1 92.9 99.9 Total Academic background F % Work experience F % Less than 5 years 5–10 years 10 71.4 1 7.1 11–15 years 2 1 14.3 92.8 1 14 99.9 14 92.8 Overall building performance F % Least satisfied Less satisfied Satisfied Very satisfied 3 21.4 7 50.0 2 1 14.3 7.1 1 92.9 14 92.8 Tables 5 and 6 show that over 92.9% of the respondents were qualified professionals with the requisite academic background and work experience in the relevant departments. The percentage age of the buildings stands at 85.7%, and the classification of the hospitals and the locations, were 92.9%. The determinants of defects were 92.9%, and the lack of building and service register and the absence of clear maintenance objectives are recorded as 85.7%. The cumulative mean score is 3.295 and the cumulative standard deviation is 0.121. This indicated that the mean ± 1 standard deviation (SD) is 70%, the mean ± 2 standard deviations are 95%, and the mean ± 3 standard deviation is 99%. The cumulative mean score of 3.30, and cumulative standard deviation 1.30. The mean for the highest and lowest rankings were 3.429 and 1.520, respectively, with 3.214 and 1.040 being constant. This indicates that the defects in the buildings principally occur due to the negligence of maintenance management based on the results of this study. The standard deviation value indicates the distribution of scores around the average mean. The smaller the standard deviation, the nearer it is to the average score. Table 7 below contains the average standard deviation of the overall defects in the hospital buildings, which is 1.229. This figure indicates that the structures are in a deplorable condition and, therefore, Ranking defect in hospital buildings Mean Std Deviation Rank Faulty fans Faulty fire alarm Fire heat extractor Damaged roof structure 3.420 3.357 3.357 3.357 1.348 1.109 1.109 1.230 1 2 3 4 Damaged taps Pipes Leakage Faulty Elevator/lifts Faulty electrical circuit Faulty sanitary appliance and fittings Faulty fire extinguisher Faulty Elevator/lifts 3.357 3.357 3.357 3.357 3.357 3.357 3.357 3.357 1.230 1.288 1.288 1.288 1.342 1.109 1.288 1.230 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Troubleshooting 3.357 1.230 13 Staircase handrail damage Faculty fire extinguisher Cracked staircases Lifts failures Faculty air conditioning system Failed furniture and fittings Blocked water closet Damaged ceiling Faulty Frames Weather and climate condition Sink leakage/blocked Collapse drains Damaged/cracked walls Damaged door locks Damaged window Floor tile failure Cracked floor Average mean 3.357 3.286 3.286 3.286 3.286 3.286 3.286 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.214 3.3 1.109 1.278 1.220 1.278 1.278 1.385 1.385 1.206 1.264 1.264 1.264 1.372 1.372 1.319 1.472 1.319 1.472 1.520 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings Table 7. Ranking defects in hospital buildings IJBPA in urgent need of maintenance. Cracked floors and defective floor tiling are prevalent defects across hospital buildings. Respondents indicated that these defects impair their buildings’ performance and raise users’ concerns about safety, as it could result in tragic accidents. Thus, it can be concluded that these two defects significantly affect the performance of buildings (Rotimi et al., 2015; Paton-Cole and Aibinu, 2021). Additional deficiencies in hospital buildings, such as faulty fire alarm systems, malfunctioning lifts, blocked water closets, damaged ceilings, and malfunctioning door locks, irritated users, who expressed frustration over random water supply outages and safety concerns about collapsing ceilings and malfunctioning door locking systems (Tan, 2018). The following section summarises several of the most serious defects and the defects rationality Table 8. Numerous factors contributed to defective windows, including a lack of protection, materials, design, workmanship, and design (Ismail et al., 2011). The findings indicate that most building users agree that the windows should be repaired regularly. According to some users, the building’s performance required maintenance, while others asserted that door malfunctions are relatively common in the structures. This finding appears counter-intuitive, given the rarity of hospital windows being open. Defective windows were caused by poor design, incompatible materials, and poor craftsmanship during manufacturing and installation (Ismail et al., 2011). Defect Damaged ceilings Cracked floor Damaged door locks Peeling paint on walls Water closet Damaged taps Showers Fans Sanitary appliance and fittings damages Floor tile s Faulty air conditioning systems Roof structure damages Sinks Damaged/cracked walls Faulty bulbs Faulty towel rail Weather and climate conditions Faulty frames Faulty elevator/lifts Lifts failures Cracked staircases Pipes leakages Wall tiles Doors Failed furniture and fittings Drains Staircases handrails damage I Faulty electrical circuit Algae on concrete floors Windows Table 8. Showing correlation of Cracked walls Faulty fire alarm defects Validity 0.565 0.642 0.458 0.687 0.667 0.787 0.656 0.798 0.632 0.798 0.573 0.562 0.465 0.421 0.343 0.425 0.487 0.515 0.558 0.437 0.686 0.735 0.625 0.756 0.554 0.582 0.456 0.423 0.345 0.421 0.478 0.522 Similarly, clogged water closets are produced by throwing useable materials into the closets, which causes leakage. Most leakages are caused by usage or misuse, exacerbated by inadequate maintenance. It could, for example, result in water seepage, tile failure, and water waste. This could wreak havoc on the users’ ability to use it. As a result of the blockages in the water closets, the users become irritated. The blocked water closets issues are less critical issues that, if rectified immediately, would avoid further deterioration and depreciation of the facilities and lengthen the useful life of the building (Ahzahar et al., 2011). Similarly, hospital buildings can suffer from high maintenance costs, including replacing defective components. These additional costs frequently result in underfunding other sectors and the use of substandard materials, all of which contribute to maintenance issues. Defects in hospital structures appear to have a negative impact on the buildings’ conditions, mainly because they can lead to accidents or disasters, as well as higher maintenance costs in the long run. The incidence of defects such as defective floors (floor tiles/floor finishes), walls (finishes/ painting), columns (finishes/painting), ventilators, doors, lighting bulbs, operable alarm bells, and lamps ceilings, among others, should be avoided, according to this study (Salleh et al., 2020). The survey results show that majority of the users resolved that walls tiles slightly or fairly critical occurred. About some percentage stated that defect walls tiles fairly critical occurred. Cracks on internal walls can be caused by poor materials, poor maintenance, usage and initial design (Olanrewaju and Tan, 2022). This finding implies that all the respondents’ responses touched on the extensive nature of defects in the hospital buildings, which reinforces this study’s assertion about the pertinence of adopting a more proactive approach toward addressing the issue of defects in hospital buildings. Numerous reports from several maintenance organisations suggest that budgetary allocations are often determined based on previous financial records. Although this approach significantly eliminates the allocation of unnecessary maintenance budgets, it is highly disadvantageous. For example, if unexpected expenditures for hospital building defects exceed the pre-planned budget, quickly obtaining additional funds could be challenging, escalating the problem. The practice of solving maintenance problems based on mere assumptions is a problematic and widely contested issue. The complaints from hospital users about the defects in their buildings and evidence from media and government reports demonstrate the retrogressive and impractical nature of such an approach to maintenance. Moreover, the prioritisation of costs over the urgency of maintenance and the inherent risks that defects pose to users of hospital buildings is highly worrisome. Unless the older hospital buildings in Malaysia are refurbished and upgraded, they cannot compete with their global contemporaries that adopt innovative maintenance services. Likewise, since the construction technique of buildings plays an indispensable role in their lifespan, it is vital to take elements such as the design, patterns, environmental standards, and available space into consideration as they remarkably influence the progression of defects in buildings. The prevalence of defects in hospital buildings can be solved foundationally by utilising durable and superior quality materials that would extend the lifespan of the buildings and drastically decrease the rate of deterioration. It is also imperative to use excellent quality and durable resources in hospital building maintenance to eradicate building defects. Additionally, to ensure that buildings do not depreciate rapidly, proactive maintenance approaches should adopt to preempt defective building components such as peeling wall paint, water leakages, drainage issues, as well as electrical and mechanical problems. Furthermore, the following defects in the hospital buildings are faulty fan, faulty fire alarm, fire heat extractor, damaged roof structure, troubleshooting, damaged taps, pipes leakage, faulty elevator/lifts, faulty electrical circuit, faulty sanitary appliance and fittings, faulty fire extinguisher, faulty elevator/lifts and staircase handrail damage. If the defects parameters greater than average mean it showed the significance level of defects in the hospital building performance. Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings IJBPA Each of the defects has significant effects on the hospital performance of each variable on the mileage. The defects devalue hospital performance would be tilted or reduces its appearances and functionality. Therefore, the listed defects must be given adequate attention. 5. Summary and recommendation This study sought to examine the defects in hospital buildings in Malaysia to proffer viable strategies to solve the highlighted problems and ameliorate the proliferation of maintenance problems. Data were collected through quantitative survey questionnaires administered to professionals in various specialisations within the healthcare industry to achieve this goal. As previously stated, hospital buildings are complex and challenging to maintain. Therefore, it is pertinent to take cognisance of problems such as user satisfaction, long-term durability and performance, as well as unforeseen circumstances during the design planning stage to preempt untimely defects and the consequences thereof. Technically speaking, the determinants of defects in the hospital buildings or required were found both in public and private hospitals. However, when compared, the rankings of the defect determinants differ in public and private healthcare facilities. According to the mean and standard deviation ranking, the defective hospital conditions identified include the following: cracked floor, floor tile failure, wall tile failure, blocked water closet, damaged window, damaged ceiling, damaged door locks, faulty shower, and faulty fans. Hospital building maintenance remains a grave issue of concern, one that is further complicated by the fact that hospitals operate twenty-four hours round the clock. Nonetheless, the effective maintenance of hospital buildings cannot be overlooked as it considerably impacts their operation, functionality and quality of the healthcare service delivery. Hospital maintenance aims to professionally manage and maintain the hospital’s physical building and its component by providing excellent services to customers at reasonable charges. This would provide a conducive environment for healthcare professionals to perform optimally their delivery of healthcare services, which will motivate them (Jesumoroti and Draai, 2021). Thus, there is an urgent need to control, monitor, and measure the maintenance performance of hospital buildings using proactive and innovative approaches. As previously mentioned, this study constitutes part of a more extensive ongoing research. Hence, it is burdened by several limitations, such as the global COVID-19 pandemic, the availability of respondents, building details, and further identification of feasible solutions to ameliorate defects and alleviate hospital buildings’ performance. Additional research areas include the identification of innovative renovation and corrective maintenance methods, the influence of rework, and equitable distribution of responsibility for the production of high-performing hospital buildings. This study offers invaluable insights for maintenance organisations and maintenance department staff who are genuinely interested in improving hospital buildings maintenance management to optimise their performance and enhance user satisfaction of hospital buildings in Malaysia and globally. This study does not only contribute to the existing body of knowledge, but it could also prove indispensable for further research regarding the redefinition of building maintenance efficiency and the performance of hospital buildings which voids of defects. References Abd Rani, N.A., Baharum, M.R., Akbar, A.R.N. and Nawawi, A.H. (2015), “Perception of maintenance management strategy on healthcare facilities”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 170, pp. 272-281. Abdul-Aziz, A.R. and Kassim, P.J. (2011), “Objectives, success and failure factors of housing publicprivate partnerships in Malaysia”, Habitat International, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 150-157. Abdul-Rahman, H., Wang, C., Wood, L.C. and Khoo, Y.M. (2014), “Defects in affordable housing projects in Klang Valley, Malaysia”, Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 272-285. Adamy, A. and Abu Bakar, A.H. (2021), “Developing a building-performance evaluation framework for post- disaster reconstruction: the case of hospital buildings in Aceh, Indonesia”, International Journal of Construction Management, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 56-77. Ahzahar, N., Karim, N.A., Hassan, S.H. and Eman, J. (2011), “A study of contribution factors to building failures and defects in construction industry”, Procedia Engineering, Vol. 20, pp. 249-255. Al-Saadi, R. and Abdou, A. (2016), “Factors critical for the success of public-private partnerships in UAE infrastructure projects: experts’ perception”, International Journal of Construction Management, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 234-248. Al-Shamlan, H.M. and Al-Mudimigh, A.S. (2011), “The Chang management strategies and processes for successful ERP implementation: a case study of MADAR”, International Journal of Computer Science Issues (IJCSI), Vol. 8 No. 2, p. 399. Al-Turki, U.M. (2011), “An exploratory study of ERP implementation in Saudi Arabia”, Production Planning and Control, Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 403-413. Ali, A.S., Kamaruzzaman, S.N., Sulaiman, R. and Peng, Y.C. (2010), “Factors affecting housing maintenance cost in Malaysia”, Journal of Facilities Management. Aljassmi, H. and Han, S. (2013), “Analysis of causes of construction defects using fault trees and risk importance measures”, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 139 No. 7, pp. 870-880. Almajed, A. and Mayhew, P. (20132013), “An investigation of the critical success factors of IT projects in Saudi Arabian public organisations”, IBIMA Business Review, p. 2013. Al-Mudimigh, A.S. (2007), “The role and impact of business process management in enterprise systems implementation”, Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 13, pp. 866-874. Amos, D., Musa, Z.N. and Au-Yong, C.P. (2020), “Performance measurement of facilities management services in Ghana’s public hospitals”, Building Research and Information, Vol. 48 No. 2, pp. 218-238. Bambang, F. (2006), in Foundation, T. and Banda Aceh (Eds), Budget Tracking: Aceh Rehabilitation and Reconstruction, GERAK Aceh. Bourne, L. and Walker, D.H. (2008), “Project relationship management and the stakeholder circle™”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business. Chan, A.P., Chan, E.H. and Chan, A.P. (2003), “Managing health care projects in Hong Kong: a case study of the north district hospital”, International Journal of Construction Management, Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 1-13. Chyu, M.C., Austin, T., Calisir, F., Chanjaplammootil, S., Davis, M.J., Favela, J., Gan, H., Gefen, A., Haddas, R., Hahn-Goldberg, S. and Hornero, R. (2015), “Healthcare engineering defined: a white paper”, Journal of Healthcare Engineering, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 635-648. Dahal, R.C. and Dahal, K.R. (2020), “A review on problems of the public building maintenance works with special reference to Nepal”, American Journal of Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 39-50. Dezdar, S. and Ainin, S. (2012), “Examining successful erp projects in middle-east and south-east asia”, American Journal of Scientific Research, Vol. 56 No. 3, pp. 13-56. Elhag, T.M.S. and Boussabaine, A.H. (1999), “Evaluation of construction costs and time attributes”, Proceedings of the 15th ARCOM Conference, Liverpool John Moores University, 15-17 September, Vol. 2, pp. 473-480. Enshassi, A., El Shorafa, F. and Alkilani, S. (2015), “Assessment of operational maintenance in public hospitals buildings in the Gaza Strip”, International Journal of Sustainable ConstructionEngineering and Technology, Vol. 6 No. 1. Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings IJBPA Evans, D.B. and Etienne, C. (2010), “Health systems financing and the path to universal coverage”, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, Vol. 88, pp. 402-403. Faqih, F. and Zayed, T. (2021), “Defect-based building condition assessment”, Building and Environment, Vol. 191, p. 107575. Finney, S. and Corbett, M. (2007), “ERP implementation: a compilation and analysis of critical success factors”, Business Process Management Journal. FMT reporter (2019), available at: www.civiltoday.com/construction/building/246-building-definitionparts components. Fore, S. and Msipha, A. (2010), “Preventive maintenance using reliability centred maintenance (RCM): a case study of a ferrochrome manufacturing company”, South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 207-234. Garip, E. (2011), “Environmental cues that affect knowing: a case study in a public hospital building”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 30, pp. 1770-1776. Gomez-Chaparro, M., Garcıa-Sanz-Calcedo, J. and Aunion-Villa, J. (2020), “Maintenance in hospitals with less than 200 beds: efficiency indicators”, Building Research and Information, Vol. 48 No. 5, pp. 526-537. Gurmu, A.T., Krezel, A. and Mahmood, M.N. (2020), “Analysis of the causes of defects in ground floor systems of residential buildings”, International Journal of Construction Management, pp. 1-8. Hashim, H.A., Sapri, M. and Azis, S.S.A. (2019), “Strategic facilities management functions for public private partnership (PPP) healthcare services in Malaysia”, Planning Malaysia, Vol. 17 No. 9. Hayat, E. and Amaratunga, D. (2014), “The impact of the local political and socio-economic condition to the capacity of the local governments in the maintenance of post-disaster road infrastructure reconstruction assets”, Procedia Economics and Finance, Vol. 18, pp. 718-726. Hinton, P.R. (2014), Statistics Explained, Routledge. Hong, E.K. (2009), “Information technology strategic planning”, IT Professional, Vol. 11 No. 6, pp. 8-15. Ismail, Z., Isa, H.M. and Takim, R. (2011), “September. Tracking architectural defects in the Malaysian hospital projects”, 2011 IEEE Symposium on Business, Engineering and Industrial Applications (ISBEIA), IEEE, pp. 298-302. Jacobson, C. and Choi, S.O. (2008), “Success factors: public works and public-private partnerships”, International Journal of Public Sector Management. Jamali, D. (2004), “Success and failure mechanisms of public private partnerships (PPPs) in developing countries: insights from the Lebanese context”, International Journal of Public Sector Management. Jandali, D. and Sweis, R. (2018), “Assessment of factors affecting maintenance management of hospital buildings in Jordan”, Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering. Jandali, D., Sweis, R.J. and Alawneh, A.R. (2018), “Factors affecting maintenance OF hospital buildings: a literature review”, International Journal of Information, Business and Management, Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 69-83. Jefferies, M., Gameson, R.O.D. and Rowlinson, S. (2002), “Critical success factors of the BOOT procurement system: reflections from the Stadium Australia case study”, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. Jesumoroti, C.O. and Cheen, K.S. (2021), “Critical insight into defects in Malaysia hospital buildings maintenance management”, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing, Vol. 945 No. 1, p. 012055. Jesumoroti, C. and Draai, W. (2021), “Analysis of construction worker’s demotivation that affect productivity in the South African Construction Industry”, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing, Vol. 654 No. 1, p. 012014. Jonsson, A.Z. and Gunnelin, R.H. (2019), “Defects in newly constructed residential buildings: owners’ perspective”, International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation. Kamal, M.M. (2006), “IT innovation adoption in the government sector: identifying the critical success factors”, Journal of Enterprise Information Management. Kemppainen, J., Tedre, M., Parviainen, P. and Sutinen, E. (2012), “Risk identification tool for ICT in international development Co-operation projects”, The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, Vol. 55 No. 1, pp. 1-26. Kuwaiti, E.A., Ajmal, M.M. and Hussain, M. (2018), “Determining success factors in Abu Dhabi health care construction projects: customer and contractor perspectives”, International Journal of Construction Management, Vol. 18 No. 5, pp. 430-445. Lam, E.W., Chan, A.P. and Chan, D.W. (2010), “Benchmarking success of building maintenance projects”, Facilities. Lavy, S., Garcia, J.A. and Dixit, M.K. (2014), “KPIs for facility’s performance assessment, Part I: identification and categorisation of core indicators”, Facilities. Lee, S., Lee, S. and Kim, J. (2018), “Evaluating the impact of defect risks in residential buildings at the occupancy phase”, Sustainability, Vol. 10 No. 12, p. 4466. Lee, S., Cha, Y., Han, S. and Hyun, C. (2019), “Application of association rule mining and social network analysis for understanding causality of construction defects”, Sustainability, Vol. 11 No. 3, p. 618. Li, B., Akintoye, A., Edwards, P.J. and Hardcastle, C. (2005), “Critical success factors for PPP/PFI projects in the UK construction industry”, Construction Management and Economics, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 459-471. Lind, H. and Muyingo, H. (2012), “Building maintenance strategies: planning under uncertainty”, Property Management. L€ofsten, H. (2018), “Maintenance and reinvestment policies: framework and principles”, International Journal of Engineering Management and Economics, Vol. 6 Nos 2-3, pp. 207-223. Macchi, M. and Fumagalli, L. (2013), “A maintenance maturity assessment method for the manufacturing industry”, Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering. Maletic, D., Maletic, M. and Gomiscek, B. (2012), “The relationship between continuous improvement and maintenance performance”, Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering. Mandal, P. and Gunasekaran, A. (2003), “Issues in implementing ERP: a case study”, European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 146 No. 2, pp. 274-283. Meng, X., Zhao, Q. and Shen, Q. (2011), “Critical success factors for transfer-operate-transfer urban water supply projects in China”, Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 27 No. 4, pp. 243-251. Mohd-Noor, N., Hamid, M.Y., Abdul-Ghani, A.A. and Haron, S.N. (2011), “Building maintenance budget determination: an exploration study in the Malaysia government practice”, Procedia Engineering, Vol. 20, pp. 435-444. Muchiri, P., Pintelon, L., Gelders, L. and Martin, H. (2011), “Development of maintenance function performance measurement framework and indicators”, International Journal ofProduction Economics, Vol. 131 No. 1, pp. 295-302. Muhammad, Z. and Johar, F. (2019), “Critical success factors of public–private partnership projects: a comparative analysis of the housing sector between Malaysia and Nigeria”, International Journal of Construction Management, Vol. 19 No. 3, pp. 257-269. Murphy, D.C., Baker, B.N. and Fisher, D. (1974), “Determinants of project success (No. NASA-CR139407)”. Ng, S.T., Wong, Y.M. and Wong, J.M. (2012), “Factors influencing the success of PPP at feasibility stage– A tripartite comparison study in Hong Kong”, Habitat International, Vol. 36 No. 4, pp. 423-432. Nguyen, L.D. and Ogunlana, S.O. (2004), .A study on project success factors in large construction projects in Vietnam, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. Nik-Mat, N.E.M., Kamaruzzaman, S.N. and Pitt, M. (2011), “Assessing the maintenance aspect of facilities management through a performance measurement system: a Malaysian case study”, Procedia Engineering, Vol. 20, pp. 329-338. Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings IJBPA Ofori, I., Duodu, P. and Bonney, S. (2015), “Establishing factors influencing building maintenance practices: ghanaian perspective”, Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, Vol. 6 No. 24, pp. 184-193. Ogunmakinde, O., Akinola, A.A. and Siyanbola, A.B. (2013), “Analysis of the factors affecting building maintenance in government residential estates in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria”, Journal of Environmental Sciences and Resources Management, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 89-103. Olanrewaju, A. and Lee, H.J.A. (2022a), “Analysis of the poor-quality in building elements: providers’ perspectives”, Frontiers in Engineering and Built Environment. Olanrewaju, A.A. and Lee, A.H.J. (2022b), “Investigation of the poor-quality practices on building construction sites in Malaysia”, Organization, Technology and Management in Construction: An International Journal, in press. Olanrewaju, A.L. and Tan, W.X. (2022), “An artificial neural network analysis of the satisfaction of hospital building maintenance services”, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing, Vol. 1218 No. 1, p. 012019. Olanrewaju, A.L.A., Khamidi, M.F. and Idrus, A. (2010), “Quantitative analysis of defects in Malaysian university buildings: providers’ perspective”, Journal of Retail and Leisure Property, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 137-149. Olanrewaju, A.A., Fang, W.W. and Tan, Y.S. (2018), “Hospital building maintenance management model”, International Journal of Engineering and Technology, Vol. 2 No. 29, pp. 747-753. Olanrewaju, A.L., Wong, W.F., Yahya, N.N.H.N. and Im, L.P. (2019), “September. Proposed research methodology for establishing the critical success factors for maintenance management of hospital buildings”, AIP conference proceedings, AIP Publishing LLC, Vol. 2157 No. 1, p. 020036. Olanrewaju, A., Tan, Y.Y. and Soh, S.N. (2021), “Defect characterisations in the Malaysian affordable housing”, International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation. Olanrewaju, A., Tan, W.X. and Gou, Z. (2022a), “Evaluation of defect in hospital buildings”, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing, Vol. 1218 No. 1, p. 012014. Olanrewaju, A., Tee, S.H., Lim, P.I. and Wong, W.F. (2022b), “Defect management of hospital buildings”, Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 1-11, and Engineering (Vol. 1218, No. 1, p. 012019). IOP Publishing. Osei-Kyei, R. and Chan, A.P. (2015), “Review of studies on the critical success factors for public– private partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013”, International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 33 No. 6, pp. 1335-1346. Osunsanmi, T.O., Aigbavboa, C.O., Oke, A. and Onyia, M.E. (2020), “Making a case for smart buildings in preventing corona-virus: focus on maintenance management challenges”, International Journal of Construction Management, pp. 1-10. Othman, N.L., Jaafar, M., Harun, W.M.W. and Ibrahim, F. (2015), “A case study on moisture problems and building defects”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 170, pp. 27-36. Paton-Cole, V.P. and Aibinu, A.A. (2021), “Construction defects and disputes in low-rise residential buildings”, Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, Vol. 13 No. 1, p. 05020016. Pinto, J.K. and Slevin, D.P. (1988a), February. Project Success: Definitions and Measurement Techniques, Project Management Institute, Newton Square, PA. Pinto, J.K. and Slevin, D.P. (1988b), June. Critical Success Factors across the Project Life Cycle, Project Management Institute, Drexel Hill, PA. Project Management Institute (2004), A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge: PMBOK Guide, 4th ed., Project Management Institute. Ralf, M. (2012), “Critical success factors in projects”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, Vol. 5, pp. 757-775. Razak, M.A.R.M.A. and Jaafar, M. (2012), “An assessment on faulty public hospital design in Malaysia”, Journal of Designþ Built, Vol. 5 No. 1. Rotimi, F.E., Tookey, J. and Rotimi, J.O. (2015), “Evaluating defect reporting in new residential buildings inNew Zealand”, Buildings, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 39-55. Sanchez-Barroso, G. and Garcıa Sanz-Calcedo, J. (2019), “Evaluation of HVAC design parameters in high- performance hospital operating theatres”, Sustainability, Vol. 11 No. 5, p. 1493. Salleh, N.M., Salim, N.A.A., Jaafar, M., Sulieman, M.Z. and Ebekozien, A. (2020), “Fire safety management of public buildings: a systematic review of hospital buildings in Asia”, Property Management. Sekaran, U. and Bougie, R. (2016), Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, John Wiley & Sons. Shohet, I.M. and Lavy, S. (2017), “Facility maintenance and management: a health care case study”, International Journal of Strategic Property Management, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 170-182. Su-Lyn, Boo (2020a), “Take legal action against medivest, HSA fire inquiry tells government”, HYPERLINK, available at: https://codeblue.galencentre.org/2020/03/12/take-legal-action-againstmedivest-hsa-fire-inquiry-tells-government/" \ohttps://codeblue.galencentre.org/2020/03/12/takelegal-action-against-medivest-hsa-fire-inquiry-tells-government/https://codeblue.galencentre.org/ 2020/03/12/take-legal- action-against-medivest-hsa-fire-inquiry-tells-government/. Su-Lyn, Boo (2020b), “Company gave HSA faulty fire extinguisher, falsified data: inquiry”, Hears: available at: https://codeblue.galencentre.org/2020/03/11/company-gave-hsa-faulty-fireextinguisher-falsified-data-inquiry-hears/. Tan, H.Y.Q. (2018), Maintenance of Hospital Building in Malaysia Unpublished Final Year Thesis, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman. Tang, L., Shen, Q., Skitmore, M. and Cheng, E.W. (2013), “Ranked critical factors in PPP briefings”, Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 164-171. Tiong, R.L., Yeo, K.T. and McCarthy, S.C. (1992), “Critical success factors in winning BOT contracts”, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 118 No. 2, pp. 217-228. Townsend, R., Butt, T.E., Francis, T.J., Kwan, J. and Peterson, A. (2017), Facilities management, obsolescence and design–the triangular relationship, Welcome to Delegates IRC 2017, p. 369. Vandesande, A. and Van Balen, K. (2016), “An operational preventive conservation system based on theMonumentenwacht model”, in Structural Analysis of Historical Constructions: Anamnesis, Diagnosis, Therapy, Controls, CRC Press, pp. 217-224. Wood, B. (2005), “Towards innovative building maintenance”, Structural Survey. Yong, Y.C. and Mustaffa, N.E. (2012), “Analysis of factors critical to construction project success in Malaysia”, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, Vol. 19, pp. 543-556. Zawawi, E.M.A., Kamaruzzaman, S.N., Ithnin, Z. and Zulkarnain, S.H. (2011), “A conceptual framework for describing CSF of building maintenance management”, Procedia Engineering, Vol. 20, pp. 110-117. Zhang, Y., Tzortzopoulos, P. and Kagioglou, M. (2019), “Healing built-environment effects on health outcomes: environment–occupant–health framework”, Building Research and Information, Vol. 47 No. 6, pp. 747-766. Zumrawi, M.M., Abdelmarouf, A.O. and Gameil, A.E. (2017), “Damages of buildings on expansive soils: diagnosis and avoidance”, International Journal of Multidisciplinary and Scientific EmergingResearch, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 108-115. Corresponding author Christtestimony Jesumoroti can be contacted at: christtestimony@yahoo.com For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com View publication stats Defects in Malaysian hospital buildings