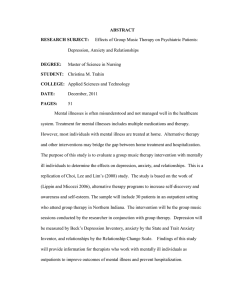

Psychology of Popular Media Binge-Watching to Feel Better: Mental Health Gratifications Sought and Obtained Through Binge-Watching Nicholas Gadino, Morgan E. Ellithorpe, Ezgi Ulusoy, Dominique S. Wirz, and Allison Eden Online First Publication, June 29, 2023. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000485 CITATION Gadino, N., Ellithorpe, M. E., Ulusoy, E., Wirz, D. S., & Eden, A. (2023, June 29). Binge-Watching to Feel Better: Mental Health Gratifications Sought and Obtained Through Binge-Watching. Psychology of Popular Media. Advance online publication. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000485 Psychology of Popular Media © 2023 American Psychological Association ISSN: 2689-6567 https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000485 Binge-Watching to Feel Better: Mental Health Gratifications Sought and Obtained Through Binge-Watching Nicholas Gadino1, Morgan E. Ellithorpe1, Ezgi Ulusoy2, Dominique S. Wirz3, and Allison Eden2 1 Department of Communication, University of Delaware Department of Communication, Michigan State University 3 Department of Mass Media and Communication Research, Fribourg University This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 2 Depression and anxiety have recently increased among young adults. So, too, have the media behaviors of binge-watching and problematic viewing. Media may be an effective tool for coping with stress and mental health challenges. The present study examines mental health management gratifications sought and obtained via media using a uses and gratifications theory approach. An online survey of undergraduates in the United States (n = 247) found that young adults report binge-watching and using media to feel better when experiencing depression and anxiety, especially if they tend toward problematic media use. For anxiety, this appears to be a successful strategy, in that participants report reduced anxiety after binge-watching. For depression, however, the results are mixed. More research is needed in this area, but this study solidifies the potential importance of coping with mental health using binge-watching of media. Public Policy Relevance Statement This study suggests that people may sometimes use binge-watching to manage their anxiety and depression, with mixed success. Using binge-watching to manage anxiety was generally more successful than for depression. People who are higher in problematic media use, which means they generally prioritize media over other life experiences, are more likely to do this than those low in problematic use. Keywords: binge watching, mental health, anxiety, depression, uses and gratifications media use is related to mental health is still unclear. On the one hand, binge-watching may reinforce negative emotional states in a vicious circle (e.g., Panda & Pandey, 2017), on the other hand, it may serve as a coping mechanism (e.g., Wagner et al., 2021). In the present study, the link between binge-watching and managing depression and anxiety is examined, as well as the perceived success of this strategy. Depression and anxiety have increased in the past few years, largely attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic and other large-scale existential crises (Kan et al., 2021; Pappa et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2020). This increase includes clinical diagnoses of depression and anxiety as well as subclinical symptom reporting. These subclinical reports may not be intense enough or last long enough to meet the clinical threshold and yet are still negatively associated with health and well-being outcomes (Maier et al., 1997). During the same period in which depression and anxiety were increasing, so were the incidences of binge-watching and problematic media use (Eales et al., 2021; Sigre-Leirós et al., 2023). However, whether Binge-Watching and Problematic Media Use Much scholarly research on binge-watching has focused on defining binge-watching (e.g., Flayelle et al., 2020; Mikos, 2016). For example, in a systematic review of peer-reviewed journal articles, Flayelle et al. (2020) discovered 28 different definitions for studies that operationalized the term, “binge-watching.” Definitions ranged from watching more than one episode, to two episodes, three episodes, or some studies defining binge-watching by consecutive hours spent viewing. However, the majority of studies have based the definition on watching several or multiple episodes in one sitting (Exelmans & Van den Bulck, 2017; Flayelle et al., 2020; Granow et al., 2018; Merikivi et al., 2018), which is the definition we use in the present study. Despite the negative connotations of the term “binge,” not all binge-watching is problematic. In order to be deemed “problematic,” media use must include aspects of behavioral addiction such as loss of control, withdrawal, and neglect of other social behaviors (Forte et al., 2021; Ort et al., 2020). Often, the distinction made between regular binge-watching and problematic binge-watching is in the Nicholas Gadino served as lead for conceptualization, investigation, and methodology and served in a supporting role for formal analysis. Morgan E. Ellithorpe served as lead for formal analysis and supervision and served in a supporting role for conceptualization, data curation, investigation, and methodology. Ezgi Ulusoy served in a supporting role for conceptualization, methodology, writing–original draft, and writing–review and editing. Dominique S. Wirz served in a supporting role for conceptualization, methodology, and writing–review and editing. Allison Eden served in a supporting role for conceptualization, methodology, and writing–review and editing. Nicholas Gadino and Morgan E. Ellithorpe contributed equally to writing– original draft and writing–review and editing. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Nicholas Gadino, Department of Communication, University of Delaware, 250 Pearson Hall, Newark, DE 19716, United States. Email: ngadino@ udel.edu 1 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 2 GADINO, ELLITHORPE, ULUSOY, WIRZ, AND EDEN outcomes—for each individual, binge-watching is unproblematic unless and until it causes negative effects on mental or physical health. In this vein, Pittman and Steiner (2021) have discussed binge-watching as an activity that can be performed in two different ways, as feast-watching or as cringe-watching. As postulated by Pittman and Steiner (2021), cringe-watching is accidental rather than planned; therefore, the viewer does not enter their bingewatching session with any specific gratifications in mind. In contrast, feast-watching is intentional and planned where the viewer has a specific gratification in mind, such as using binge-watching as a social activity. In their study, Pittman and Steiner (2021) found that unplanned binge sessions led to decreased levels of well-being while planned binge-watching sessions led to increased levels of well-being. Pittman and Steiner (2021), associate problematic usage of binge-watching with decreased levels of well-being, whereas less problematic usage is related to positive mental health outcomes. Mental Health Outcomes According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, text revision, “Depression, otherwise known as major depressive disorder or clinical depression, is a common and serious mood disorder. Those who suffer from depression experience persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness and lose interest in activities they once enjoyed. Aside from the emotional problems caused by depression, individuals can also present with a physical symptom such as chronic pain or digestive issues. To be diagnosed with depression, symptoms must be present for at least 2 weeks.” (Fazel, 2022). According to the National Institute of Mental Health, anxiety, or Generalized Anxiety Disorder, “is characterized by excessive anxiety and worry about a variety of events or activities (e.g., work or school performance) that occurs more days than not, for at least 6 months. People with generalized anxiety disorder find it difficult to control their worry, which may cause impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning” (National Institute of Mental Health, n.d.). In a study which examined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, physical activity, as well as sedentary behaviors of individuals, Marashi et al. (2021) found that individuals reported moderate levels of stress and anxiety during the pandemic. Respondents in their study reported desiring to be physically active in order to self-treat their stress and anxiety, however, many felt government-mandated closures of gyms and recreational centers, as well as increased poor mental health, made increased physical activity difficult to achieve. Finally, government-mandated limitations on public gatherings and activities outside the home forced individuals to remain inside frequently during the COVID-19 pandemic, contributing to poor mental health. Though physical activity may serve as a self-treatment for symptoms of anxiety and depression (Marashi et al., 2021), individuals may need to access other outlets in order to combat anxiety and depression, especially when physical activity is difficult to achieve and sedentary behavior is more frequent than normal. Potts and Sanchez (1994) found that television viewing can aid an individual in escaping depressive moods. Additionally, in investigating the screen time behavior of young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, Wagner et al. (2021) found that individuals increased their TV watching, smartphone use, and use of streaming services in order to stay connected with others, which was found as a coping tool for stress and improved mental health. Mental Health Outcomes of Binge-Watching A great deal of research has examined the relationship between binge-watching and mental health (e.g., Ahmed, 2017; Boudali et al., 2017; Sun & Chang, 2021; Sung et al., 2015; Tefertiller & Maxwell, 2018). Several studies have indicated that problematic binge use is associated with increased loneliness, depression, loss of control, poor sleep quality, insomnia, and overall fatigue (Gangadharbatla et al., 2019; Starosta et al., 2020; Steins-Loeber et al., 2020; Sung et al., 2015). For example, Ahmed (2017) found that younger individuals tend to binge-watch alone, which may lead to increased feelings of loneliness and depression. Starosta et al. (2020) found that those who engage in binge-watching do so to avoid life’s daily problems, and neglect schoolwork, chores, and other duties. Steins-Loeber et al. (2020) concluded that as symptoms of depression increased, binge-watching may serve as a distraction from those negative thoughts and feelings, but may also lead to social problems and negligence of duties. Sung et al. (2015) demonstrate that binge-watching is related to not only depression but also loneliness, and that high rates of series-watching could lead to personal feelings of guilt, anxiety, helplessness, and depression while also damaging interpersonal relationships. They also found positive associations between problematic binge-watching and social interaction anxiety, anxiety, depression, and loneliness. Sun and Chang (2021, p. 6) found problematic binge-watching was associated with, “increased social interaction anxiety risk”, commenting that individuals who experience anxiety concerning social interactions may seek such interactions vicariously through binge-watching content. Lastly, Vaterlaus et al. (2019) found that binge-watching among college students could lead to missed social opportunities and strained friendships. In addition, they found that binge-watching was reported to be an unhealthy way of dealing with mental health challenges such as “depressive-like symptoms” (p. 476). In sum, the bulk of this research shows binge-watching either as a casual factor or otherwise related to negative mental health outcomes and well-being. However, the relationship between binge-watching and negative mental health has not been consistent. Tefertiller and Maxwell (2018), for example, found a negative relationship between depression and binge-watching—indicating that there may be moderating factors that influence whether binge-watching will have a positive, negative, or no relationship with mental health outcomes. Earlier works on binge-watching (or “marathon-viewing” e.g., Perks, 2015) have shown that individuals sometimes use binge-watching to help their mental health. Perks’ interviews (2019) demonstrated individuals who were suffering from an injury sought comfort in binge-watching to distract themselves from the pain and boredom. Similarly, those who were suffering from mental health problems also used bingewatching as a way to escape their stress (Perks, 2019). The use of media for coping with mental health and with stress in general has been studied in various contexts (e.g., Anderson et al., 1996; Prestin & Nabi, 2020; Nabi et al., 2017), but most lately in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, one study found that university students reported using media to cope with stress and anxiety during social distancing (Eden et al., 2020). Eden et al. (2020) found that different kinds of media content, This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. BINGE-WATCHING TO FEEL BETTER such as hedonic versus eudaimonic, were differentially associated with well-being when used for coping with either stress or anxiety, however, did not specifically examine binge-watching. In terms of binge-watching, Rahman and Arif (2021) found that individuals who experienced boredom and stress caused by the COVID-19 lockdown experienced relief from these emotions through bingewatching. Finally, Sigre-Leirós et al. (2023) found that bingewatching for social gratifications was protective for mental health during COVID-19, but that problematic binge-watching was maladaptive and associated with worse mental health over time. Much of the research finding positive health outcomes from binge-watching assumes that viewers are active audience members, choosing their content with control and engagement as compared to traditional, linear, “passive” broadcast or cable TV (Groshek et al., 2018; Pittman & Sheehan, 2015; Rahman & Arif, 2021; Steiner & Xu, 2020). This concept of an active audience stems from the theory of Uses and Gratifications, which assumes an active media audience and that active media users will seek out specific content to fulfill particular needs or goals (Katz et al., 1973). The uses and gratifications framework suggests that people select specific media content in order to satisfy certain needs such as social connection, entertainment, or information, and that this media content may gratify the user’s needs but may also lead to unintended effects (Katz et al., 1973). Since its introduction, uses and gratifications frameworks have been applied to understanding motivations for using different media platforms and content. While Uses and Gratifications theory assumes an active audience (Katz et al., 1973), over time, scholars have debated whether or not audiences were active or passive in their media consumption. Earlier researchers claimed that audience members became more passive consumers with greater television consumption (e.g., Gerbner & Gross, 1976). Later scholars contended that audience members became more active, attentive consumers of media content as their viewing options increased (Sender, 2012). In the context of binge-watching, researchers have claimed that binge viewers are both active (Rahman & Arif, 2021) and passive (Sung et al., 2015) consumers, with active consumers reporting positive outcomes and passive consumers reporting negative outcomes. In terms of mental health and binge-watching behaviors, we suggest that users could be seeking media for coping with stress and strain (Wolfers & Schneider, 2021), or as a method of recovering depleted resources (Reinecke et al., 2011). The idea that binge-watching can help individuals to cope with their physical and mental health problems also corresponds with the media use for recovery hypothesis (Reinecke et al., 2011, 2014). The recovery hypothesis states that media use can help people recover from daily stress factors, such as work and school, and this is a factor in increasing overall well-being. For example, individuals who were stressed performed much better upon engaging with media content they enjoyed (Reinecke et al., 2011). Recent research on binge-watching has also found support for the recovery hypothesis, suggesting that binge-watching to recover from stress is beneficial for mental health and well-being (Erdmann & Dienlin, 2022; Granow et al., 2018). Therefore, for many users, binge-watching is not likely to be associated with negative outcomes, but instead with positive mental health and well-being. We are interested in understanding the circumstances and motivations that play a role in determining whether a person experiencing depression and anxiety will come out of binge-watching with positive or negative outcomes. 3 The Current Study The present study aimed to further the current literature on the relationship between binge-watching and mental health by examining the specific role of mental health gratifications or purposefully using media to manage mental health. This adds to the literature on media use for coping by asking participants directly about their use of binge-watching when they feel depressed and anxious. We also examine the extent to which the gratification of mental health management is realized via binge-watching. We expect that participants who are experiencing subclinical depression and anxiety may be more likely to report seeking mental health gratifications through binge-watching. This is based on previous research finding that depression (Steins-Loeber et al., 2020) and anxiety (Boursier et al., 2021) were both associated with increased binge-watching, with both articles inferring that this increased use was likely due to a desire to manage mental health. When combining this work with other research on media use for coping with stress and other negative emotions (e.g., Eden et al., 2020), we expect that participants who report greater depression and anxiety will also be more likely to report seeking mental health gratifications using binge-watching. Hypothesis 1a: Increased depression will be associated with increased mental health gratifications sought via binge-watching. Hypothesis 1b: Increased anxiety will be associated with increased mental health gratifications sought via binge-watching. In addition to mental health, previous problematic use of bingewatching should also be associated with mental health gratifications sought via binge-watching. For example, problematic use of media was associated with seeking gratifications of entertainment and information via binge-watching (Tukachinsky & Eyal, 2018). To the extent that problematic use is related to addictive behavior such as increased use, tolerance, and withdrawal, it should be associated with turning to binge-watching for a variety of reasons, including mental health gratifications. Hypothesis 2: Increased problematic media use will be associated with increased mental health gratifications sought via binge-watching. Given the expected main effects of depression and anxiety and problematic media use on mental health gratifications, it is possible that these relationships are not just parallel but are also multiplicative. In particular, we might expect an interaction between mental health and problematic media use such that people with depression and/or anxiety who are also high in problematic media use may be more likely to turn to media to manage their mental health than other methods of management. Someone without problematic media use, however, may be more likely to seek to manage their mental health through nonmedia means. This is because problematic media users are more likely than nonproblematic users to spend time with media regardless of other activities or relationships that are important in their lives (Horvath, 2004). When problematic users are experiencing depression and anxiety, states in which they might already be predisposed to seek media for coping, the more problematic their media use the more likely they should be to seek media. 4 GADINO, ELLITHORPE, ULUSOY, WIRZ, AND EDEN Hypothesis 3a: Depression and problematic media use will interact to predict mental health gratifications sought via bingewatching, such that those who are higher in both depression and problematic media use will be the most likely to report seeking mental health gratifications via binge-watching. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Hypothesis 3b: Anxiety and problematic media use will interact to predict mental health gratifications sought via bingewatching, such that those who are higher in both anxiety and problematic media use will be the most likely to report seeking mental health gratifications via binge-watching. Unfortunately for media users, gratifications sought may not always translate into gratifications obtained (Palmgreen & Rayburn, 1979, 1982; Wenner, 1986). Each aspect provides unique explanatory power for the patterns in which people seek certain kinds of media to fulfill certain gratifications, and how those patterns may change over time. Therefore, it is important to not only measure mental health gratifications sought but also whether those gratifications are obtained. In the present study, mental health gratifications obtained are defined in terms of whether participants report feeling more or less depressed or anxious after binge viewing. In this case, there is less specific research on which to base a directional hypothesis—often research suggests both positive and negative effects, and so we present a research question: RQ: What is the relationship between mental health gratifications sought via binge-watching and binge-watching gratifications obtained? In sum, our hypotheses and research question combine into a moderated mediation model, with depression or anxiety and problematic media use interacting to predict mental health gratifications sought as a mediator, and mental health gratifications obtained as the outcome. See Figure 1 for a generic conceptual model. Method Participants Participants were 247 undergraduates at a large university in the midwestern United States who participated for course credit through a student participant pool. The mean age was 19.71 years (SD = 1.50), 148 (59.92%) identified as female, 97 (39.27%) identified as male, and two (0.81%) identified as nonbinary/other. Racial and ethnic identities included 182 (73.39%) White, 23 (9.27%) Figure 1 Conceptual Model Asian, 20 (8.06%) Black or African American, nine (3.63%) multiracial, seven (2.82%) Hispanic or Latino, two (0.81%) Arab or Middle Eastern, one (0.40%) other, and four (1.61%) declined to respond. Participants who reported they only watch 1 episode at a time (n = 18) were not included in the analysis, leaving a total sample of n = 229. Procedure Participants were invited to take the online survey via the university’s student participant pool. After indicating consent to participate, participants were asked about their problematic series watching, gratifications sought from television viewing, gratifications obtained from television viewing, and their current mental health in a randomized order. They answered demographic questions at the end of the study before they were given debriefing information. The procedure and measures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Measures Depression Depression was measured using the PROMIS short form (fouritem) depression scale (Pilkonis et al., 2011), using a 1 = never to 5 = always scale (M = 2.10, SD = 0.99, Cronbach α = .92). Anxiety Anxiety was measured using the PROMIS short form (four-item) anxiety scale (Pilkonis et al., 2011), using a 1 = never to 5 = always scale (M = 2.59, SD = 0.97, Cronbach α = .88). Problematic Series Watching Problematic series watching was measured with the Problematic Series Watching Scale (PSWS) which consists of five items on a scale of 1 = never to 5 = always. The original scale (Orosz et al., 2016) is six items, but one of the items, “watched series in order to reduce feelings of guilt, anxiety, helplessness and depression?” was considered too similar to the gratifications sought and obtained by the authors. The item was removed, leaving five items (M = 2.28, SD = 0.87, Cronbach α = .86). Mental Health Gratifications Sought Gratifications sought for mental health management were operationalized via two items for each of depression and anxiety, measured on a 1 = never to 5 = always scale. The measure was developed by the authors, based on existing gratifications and need satisfaction measures. These were embedded within a list of activities people may engage in, with the prompts, “Think of a time when you were feeling more [depressed/anxious] than usual. To what extent would you say you did the following activities?.” The crucial, relevant items were, “binge-watched TV” and “used media specifically to help me feel better.” Filler items included activities such as, “exercised more” and “slept a long time.” Central tendencies for the crucial items were as follows: bingewatched TV when depressed (M = 3.25, SD = 1.07), used media to feel better when depressed (M = 3.13, SD = 1.16), binge-watched BINGE-WATCHING TO FEEL BETTER TV when anxious (M = 3.15, SD = 1.10), used media to feel better when anxious (M = 3.13, SD = 1.19). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Mental Health Gratifications Obtained Whether or not participants obtained the gratifications sought was operationalized as whether they reported feeling more or less depressed/anxious after binge-watching. This was measured with the prompt, “binge-watching TV…” and the items were (−5 = strongly disagree to +5 = strongly agree scale): “helps me feel less depressed” (M = 1.47, SD = 2.45), “makes me feel more depressed” (M = −1.34, SD = 2.54), “helps me feel less anxious” (M = 1.78, SD = 2.27), and “makes me feel more anxious” (M = −1.91, SD = 2.45). Binge Frequency Participants were asked to indicate how often they watch more than two consecutive episodes of a series in one sitting, with response options from 1 = less than once per month to 6 = daily (M = 4.53, SD = 1.51). This variable was included as a covariate in the analysis. Statistical Analysis Analyses were conducted using path models, one for each of depression and anxiety, using structural equation modeling in Stata 17 and the Satorra–Bentler adjustment (Satorra & Bentler, 1994) for robust standard errors due to the measures being slightly elevated in kurtosis (ranging 2.01 to 3.73), though none of the measures were skewed (ranging −0.47 to 0.88). Depression and anxiety were treated separately because the PROMIS depression and anxiety scales were too highly correlated (r = .77) to avoid multicollinearity if combined. Both of these models were tested first as mediation models only, in order to obtain the main effects of PSWS and depression and/or anxiety, and then the interaction between PSWS and depression/anxiety was added to make the models moderated mediation models. In each model, PSWS and depression (or anxiety) and their interaction predicted the two gratifications-sought items (binge when depressed/anxious and use media to feel better when depressed/anxious). Gratifications sought and the main effects of PSWS and depression (or anxiety) predicted gratifications obtained related to depression and anxiety, with all variables treated continuously as measured. Participant sex was included as a covariate due to significant differences in depression and anxiety when comparing males and females. The two nonbinary/other participants were included in the analyses, and sex was treated as a multinomial variable; however, any conclusions regarding this group should be avoided due to the very small sample size. Binge frequency was also included as a covariate to account for individual differences in how often they binge-watch as a factor in their likelihood of reporting binge-watching when depressed or anxious. The error terms of the endogenous variables were allowed to correlate at each stage of the model (i.e., the two mediators together and the two outcomes together). Indirect effects were obtained using 5,000 bias-corrected bootstrapped samples. Results Full statistical results can be found in Tables 1 and 2. 5 Depression Examining depression first, we find that depression was not significantly associated with reporting binge-watching when depressed, but it was significantly and positively associated with reporting using media in general to feel better when depressed. This provides partial support for H1a. Problematic viewing was significantly positively associated with both gratifications sought, in that the more participants reported problematic binge viewing the more they were likely to report binge-watching when they felt depressed and more likely to report using media to feel better when depressed. This supports Hypothesis 2. Adding the interaction term finds that there was not a significant interaction between depression and problematic viewing, which means H3a was not supported in the context of depression. Using media to feel better when depressed was significantly associated with participants reporting both that they felt less depressed after binge-watching, while the relationship did not quite reach significance for feeling more depressed after binge-watching (p = .053). Problematic viewing was also associated with more reports of feeling less depressed after binge-watching. This provides an answer for RQ1 for depression. The indirect effects were tested in the main effects model only, given the nonsignificant interaction between PSWS and depression. Three indirect effects paths were significant. First, problematic binge viewing was significantly associated with feeling less depressed when mediated by using media to feel better when depressed. Second, depression was also significantly associated with feeling less depressed when mediated by using media to feel better when depressed. And third, depression was also significantly associated with feeling more depressed when mediated by using media to feel better. Therefore, there is somewhat of an ambivalent effect on mental health gratifications obtained from binge-watching in the context of depression. Anxiety Examining anxiety, we find that anxiety was significantly associated with reporting using media to feel better when anxious, but not with binge-watching when anxious. This provides partial support for H1b. Problematic viewing was significantly positively associated with participants reporting binge-watching when they felt anxious, but not with using media to feel better when anxious. This provides partial support for H2. Adding the interaction term finds that there was not a significant interaction between anxiety and problematic viewing, which means H3b was not supported. Binge-watching when anxious was significantly associated with participants reporting that they feel less anxious after binge-watching. Anxiety gratifications sought were not significantly associated with reporting feeling more anxious after binge-watching. Problematic viewing was also associated with more reports of feeling more anxious after binge-watching, while anxiety was associated with reports of feeling less anxious after binge-watching. This provides an answer for RQ1 in the context of anxiety. The indirect effects were again tested in the main effects model only, given the nonsignificant interaction between PSWS and anxiety. There was only one significant indirect effect path. Problematic binge-viewing was significantly associated with feeling less anxious when mediated by binge-watching when anxious. Therefore, the outcomes of mental health gratifications sought for anxiety are 6 GADINO, ELLITHORPE, ULUSOY, WIRZ, AND EDEN Table 1 Path Model Regression Results for Depression as the Context This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Binge when depressed Independent variable(s) b PSWS Depression Sex (male = 0) Female Non-Binary/other Binge often Binge when depressed Use media to feel better 0.35 0.09 0.20 − 1.06 0.23 — — [−0.05, 0.45] [− − 1.43, − 0.69] [0.14, 0.32] — — PSWS × Depression −0.06 [−0.21, 0.08] R 2 95% CI [0.20, 0.49] [−0.04, 0.22] Use media to feel better b 0.18 0.21 PSWS → binge → less depressed PSWS → use media → less depressed PSWS → binge → more depressed PSWS → use media → more depressed Depression → binge → less depressed Depression → use media → less depressed Depression → binge → more depressed Depression → use media → more depressed [0.00, 0.37] [0.04, 0.38] b 95% CI Feel more depressed b 0.42 0.24 [0.06, 0.77] [−0.03, 0.50] 0.03 0.27 95% CI [−0.36, 0.42] [−0.00, 0.54] 0.31 0.06 −0.02 — — [0.00, 0.61] [−2.90, 3.03] [−0.13, 0.08] — — −0.11 0.45 0.26 0.27 0.31 [−0.71, 0.50] [−2.47, 3.37] [0.04, 0.47] [−0.09, 0.63] [0.03, 0.60] − 0.99 −0.83 − 0.25 0.25 0.27 [− − 1.54, − 0.44] [−1.70, 0.03] [− − 0.46, − 0.03] [−0.08, 0.59] [−0.00, 0.54] 0.05 [−0.13, 0.24] — — — — 0.33 Indirect effects 95% CI Feel less depressed 0.09 0.19 b 95% CI 0.09 0.06 0.08 0.05 0.02 0.07 0.02 0.06 [−0.03, 0.27] [0.00, 0.18] [−0.04, 0.21] [−0.00, 0.16] [−0.01, 0.10] [0.01, 0.19] [−0.01, 0.10] [0.00, 0.17] 0.22 Note. The results reported below for all variables except the interaction are from the main effects model; the interaction results are for the interaction only. Because the interaction was not significant, it was the main effects model that was used to run indirect effects testing. Coefficients are unstandardized; indirect effects were obtained with 5,000 bias-corrected bootstrap samples; significant coefficients and confidence intervals (at p , .05) are bolded for ease of interpretation. PSWS = Problematic Series Watching Scale. more consistently positive compared to depression, but only one mediation path was significant. Discussion Given recent reports on the state of mental health of young adults (Kan et al., 2021; Pappa et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2020) and the concomitant increase in binge-watching—both nonproblematic and problematic (Eales et al., 2021; Sigre-Leirós et al., 2023), the present study examined the mental health gratifications sought and obtained from binge-watching. The results demonstrated that individuals report binge-watching in order to manage depression and anxiety. Whether or not they perceive this as successful management is dependent upon the specific gratification sought from binge-watching, and on whether the mental health context is depression or anxiety. There was a mixed outcome for depression, in that both people reporting problematic media use and people reporting greater depression were more likely to report using media to feel better when depressed. Using media specifically to feel better when feeling depressed was significantly associated with decreased depression feelings after media use. However, the indirect effects of depression on outcomes through using media to feel better when depressed were significant in both directions—for feeling less depressed and for feeling more depressed, despite the lack of a significant relationship between using media to feel better and experiencing more depression (p = .053). This is possible given the way the indirect effect is calculated (A. F. Hayes, 2022). Therefore, problematic media use was indirectly associated with both increased and decreased depression symptom reporting, indicating an ambivalent effect of problematic viewing on depression—but perhaps slightly more strongly in favor of reduced depression. It should be noted that many longitudinal studies have found an association between time spent viewing television and later depression (Bickham et al., 2015; Boers et al., 2019; Primack et al., 2009), which is in contrast to the present study. While the present study looked specifically at using media to manage depression and the contradictory studies looked at general use, the fact remains that there is a disconnect. Due to these contrasts with previous research, we urge more attention to be paid to this topic in the future. Additionally, people reporting higher anxiety were more likely to report using media to feel better when anxious, and problematic media users were more likely to report binge-watching when anxious. Both of these strategies were associated with decreased reported anxiety after media use. However, only the indirect effect of problematic use on decreased anxiety through binge-watching when anxious was significant. Therefore, in the context of anxiety, the strategy of bingewatching might be effective. As with depression, much of the longitudinal research on television use and anxiety finds a relationship with more anxiety, rather than less (Allen et al., 2019; Maras et al., 2015). However, there has been more specific work with anxiety and coping using media (e.g., Eden et al., 2020), which supports the possibility that asking specifically about using media to manage anxiety symptoms as opposed to looking at television use in general as time spent is the likely reason for these disparate findings. The results of this study shed some light on the disparate outcomes in previous literature for the relationships between bingewatching, problematic media use, and mental health. The results of the present study are more supportive of the media use for recovery hypothesis and research on media use to cope with stress (Eden et al., 2020; Reinecke et al., 2011, 2014), in that the results suggest that problematic media use can actually yield positive results for some people in some contexts. Although many studies have found that binge-watching and problematic media use are associated with 7 BINGE-WATCHING TO FEEL BETTER Table 2 Path Model Regression Results for Anxiety as the Context This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Binge when anxious PSWS Anxiety Sex (male = 0) Female Non-Binary/other Binge often Binge when anxious Use media to feel better 0.32 0.12 [0.14, 0.50] [−0.03, 0.27] 0.09 0.21 [−0.13, 0.30] [0.04, 0.38] 0.11 0.41 [−0.21, 0.42] [0.14, 0.68] 0.57 0.26 0.08 −0.57 0.22 — — [−0.18, 0.34] [−1.44, 0.31] [0.13, 0.31] — — 0.33 1.11 0.02 — — [−0.01, 0.67] [−0.66, 2.87] [−0.10, 0.13] — — −0.14 1.66 [−0.72, 0.45] [0.28, 3.04] − 0.76 0.99 [− − 1.36, − 0.16] [−2.38, 4.36] 0.53 0.21 [0.19, 0.86] [−0.06, 0.49] −0.08 0.24 [−0.41, 0.25] [−0.04, 0.52] 0.02 [−0.17, 0.21] −0.07 [−0.29, 0.15] — — — R 0.26 Indirect effects PSWS → binge → less anxious PSWS → use media → less anxious PSWS → binge → more anxious PSWS → use media → more anxious Anxiety → binge → less anxious Anxiety → use media → less anxious Anxiety → binge → more anxious Anxiety → use media → more anxious 95% CI 0.08 b 95% CI Feel more anxious B 2 b Feel less anxious Independent variable(s) PSWS × Anxiety 95% CI Use media to feel better 0.19 b 95% CI 0.17 0.02 −0.03 0.02 0.06 0.05 −0.01 0.05 [0.05, 0.35] [−0.02, 0.12] [−0.18, 0.07] [−0.02, 0.12] [−0.00, 0.19] [−0.00, 0.15] [−0.09, 0.02] [−0.00, 0.16] B 95% CI [0.13, 1.01] [−0.07, 0.60] — 0.09 Note. The results reported below for all variables except the interaction are from the main effects model; the interaction results are for the interaction only. Because the interaction was not significant, it was the main effects model that was used to run indirect effects testing. Coefficients are unstandardized; indirect effects were obtained with 5,000 bias-corrected bootstrap samples; significant coefficients and confidence intervals (at p , .05) are bolded for ease of interpretation. PSWS = Problematic Series Watching Scale. worse mental health (Gangadharbatla et al., 2019; Starosta et al., 2020; Steins-Loeber et al., 2020; Sung et al., 2015), others have found the opposite, especially when considering binge and problematic use as coping behaviors for mental health and stress (e.g., Perks, 2015, 2019). The present study’s participants reported that they do generally feel better when they use media to manage certain aspects of their mental health, without strong evidence that such behaviors make them feel worse. The current study demonstrates an agentic, purposeful use of media and binge watching which, thus far, has been ignored in the current literature in favor of problematizing binge-watching and mental health. Adopting a Uses and Gratifications framework for this study, we found partial support for the notion of seeking out media in bingewatching fashion to cope with feelings of anxiety. Overall, this study advances the application of the Uses and Gratifications theory in terms of mental health outcomes. While other studies have examined binge-watching from a Uses and Gratifications perspective (Groshek et al., 2018; Pittman & Sheehan, 2015; Rahman & Arif, 2021; Steiner & Xu, 2020), the current study finds that media users may turn to binge watching to cope with anxiety and depression emotions. This is a specific contribution to the available scholarly applications of Uses and Gratifications theory and is the latest example of how the theory can be applied in both use of modern media context as well as a mental health context. Limitations and Future Research The present study was cross-sectional, meaning causality cannot be assumed, and recall for media use when feeling depressed or anxious may be inaccurate due to faulty memory or due to current mental health states coloring the recalled experiences. It is also possible that people who are high in problematic media use may be more likely to recall their media use as beneficial in order to justify their use. Relatedly, whether participants felt better or worse after bingewatching was also based on their perception, not on reality. Despite these issues, however, the results remain useful as an initial step in uncovering how mental health management gratifications are sought by people experiencing depression and anxiety. Future research should consider longitudinal or experimental designs to better pinpoint these relationships. Additionally, the sample in the present study was a convenient sample of undergraduates. While young adults are an important group to study in this context given the research on the state of their mental health in the past few years (Kan et al., 2021; Pappa et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2020), it remains an issue that the results of this study may not be generalizable to other populations such as older adults or children. Furthermore, this undergraduate sample may have encountered external factors which dictated their media consumption schedule, like their responsibilities to academic course work, or parttime employment, for example. Populations outside of an undergraduate sample likely would engage in media use around different externally influential factors, like the demands of a full-time job. Future research should consider studying these topics in other populations. Finally, the mental health gratifications sought and obtained were measured using single-item measures, which are statistically not ideal for capturing what is likely a complex phenomenon. This was an initial attempt to ascertain whether there is something worth studying in this area, and the present results are suggestive of that. However, in the future, it would be better if a scale for mental health management gratifications sought and obtained could be 8 GADINO, ELLITHORPE, ULUSOY, WIRZ, AND EDEN created and validated in order to lend more strength to the results. Additionally, conceptual distinctions between binge and problematic viewing behaviors are needed, in order to establish the discriminant validity of the constructs (e.g., Davidson et al., 2022). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Conclusion Media use for coping with mental health such as depression and anxiety is likely to continue to be a strategy to contend with. Our results suggest that people with anxiety and depression may experience some relief by using media to feel better or by binge-watching while feeling anxious. This is in line with the media use for recovery hypothesis and research suggesting using media to cope with stress can be beneficial (Reinecke et al., 2011). Although more work is needed in this context, the present results are compelling to suggest that mental health management is a gratification sought by people experiencing anxiety and depression. Whether those gratifications are obtained is another story. References Ahmed, A. A.-A. M. (2017). A new era of TV-watching behavior: Binge watching and its psychological effects. Media Watch, 8(2), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.15655/mw/2017/v8i2/49006 Allen, M. S., Walter, E. E., & Swann, C. (2019). Sedentary behaviour and risk of anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.081 Anderson, D. A., Collins, P. A., Schmitt, K. L., & Jacobvitz, R. S. (1996). Stressful life events and television viewing. Communication Research, 23(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365096023003001 Bickham, D. S., Hswen, Y., & Rich, M. (2015). Media use and depression: Exposure, household rules, and symptoms among young adolescents in the USA. International Journal of Public Health, 60(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-014-0647-6 Boers, E., Afzali, M. H., Newton, N., & Conrod, P. (2019). Association of screen time and depression in adolescence. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(9), 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1759 Boudali, M., Hamza, M., Halayem, S., Bouden, A., & Belhadj, A. (2017). Time perception and binge watching among medical students with depressive symptoms. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 27(Supplement 4), S811–S812. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-977X(17)31469-4 Boursier, V., Musetti, A., Gioia, F., Flayelle, M., Billieux, J., & Schimmenti, A. (2021). Is watching TV series an adaptive coping strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic? Insights from an Italian Community sample. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, Article 599859. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyt.2021.599859 Davidson, B. I., Shaw, H., & Ellis, D. A. (2022). Fuzzy constructs in technology usage scales. Computers in Human Behavior, 133, Article 107206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107206 Eales, L., Gillespie, S., Alstat, R. A., Ferguson, G. M., & Carlson, S. M. (2021). Children’s screen and problematic media use in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Development, 92(5), e866–e882. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13652 Eden, A. L., Johnson, B. K., Reinecke, L., & Grady, S. M. (2020). Media for coping during COVID-19 social distancing: Stress, anxiety, and psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 577639. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577639 Erdmann, E., & Dienlin, T. (2022). Binge-watching, self-determination, and well-being. Journal of Media Psychology, 34(6). 383–394. https://doi.org/ 10.1027/1864-1105/a000334 Exelmans, L., & Van den Bulck, J. (2017). Binge viewing, sleep, and the role of pre-sleep arousal. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(08), 1001– 1008. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6704 Fazel, F. (2022). Depression definition and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Psycom.net. https://www.psycom.net/depression/major-depressive-disorder/ dsm-5-depression-criteria Flayelle, M., Maurage, P., Di Lorenzo, K. R., Vögele, C., Gainsbury, S. M., & Billieux, J. (2020). Binge-watching: What do we know so far? A first systematic review of the evidence. Current Addiction Reports, 7(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00299-8 Forte, A., Orri, M., Brandizzi, M., Iannaco, C., Venturini, P., Liberato, D., Battaglia, C., Nöthen-Garunja, I., Vulcan, M., Brusìc, A., Quadrana, L., Cox, O., Fabbri, S., & Monducci, E. (2021). “My life during the lockdown”: Emotional experiences of European adolescents during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), Article 7638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph18147638 Gangadharbatla, H., Ackerman, C., & Bamford, A. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of binge-watching for college students. First Monday, 24(12), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v24i12.9667 Gerbner, G., & Gross, L. (1976). Living with television: The violence profile. Journal of Communication, 26(2), 172–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1460-2466.1976.tb01397.x Granow, V. C., Reinecke, L., & Ziegele, M. (2018). Binge-watching and psychological well-being: Media use between lack of control and perceived autonomy. Communication Research Reports, 35(5), 392–401. https:// doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2018.1525347 Groshek, J., Krongard, S., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Netflix and ill? Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Social Media and Society— SMSociety ’18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3217804.3217932 Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). Guilford Publications. Horvath, C. W. (2004). Measuring television addiction. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 48(3), 378–398. https://doi.org/10 .1207/s15506878jobem4803_3 Kan, F. P., Raoofi, S., Rafiei, S., Khani, S., Hosseinifard, H., Tajik, F., Raoofi, N., Ahmadi, S., Aghalou, S., Torabi, F., Dehnad, A., Rezaei, S., Hosseinipalangi, Z., & Ghashghaee, A. (2021). A systematic review of the prevalence of anxiety among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.073 Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509–523. https://doi.org/10 .1086/268109 Maier, W., Gänsicke, M., & Weiffenbach, O. (1997). The relationship between major and subthreshold variants of unipolar depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 45(1–2), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00058-x Maras, D., Flament, M. F., Murray, M., Buchholz, A., Henderson, K. A., Obeid, N., & Goldfield, G. S. (2015). Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Preventive Medicine, 73, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.029 Marashi, M. Y., Nicholson, E., Ogrodnik, M., Fenesi, B., & Heisz, J. J. (2021). A mental health paradox: Mental health was both a motivator and barrier to physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE, 16(4), Article e0239244. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239244 Merikivi, J., Salovaara, A., Mäntymäki, M., & Zhang, L. (2018). On the way to understanding binge watching behavior: The over-estimated role of involvement. Electronic Markets, 28(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10 .1007/s12525-017-0271-4 Mikos, L. (2016). Digital media platforms and the use of TV content: Binge watching and video-on-demand in Germany. Media and Communication, 4(3), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.542 Nabi, R. L., Pérez Torres, D., & Prestin, A. (2017). Guilty pleasure no more. Journal of Media Psychology, 29(3), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1027/ 1864-1105/a000223 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. BINGE-WATCHING TO FEEL BETTER National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Generalized anxiety disorder. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/ statistics/generalized-anxiety-disorder#:~:text=Definition%20Generalized %20anxiety%20disorder%20is%20characterized%20by%20excessive Orosz, G., Bő the, B., & Tóth-Király, I. (2016). The development of the Problematic Series Watching Scale (PSWS). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.011 Ort, A., Wirz, D. S., & Fahr, A. (2020). Is binge-watching addictive? Effects of motives for TV series use on the relationship between excessive media consumption and media addiction. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 13, Article 100325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100325 Palmgreen, P., & Rayburn, J. D. (1979). Uses and gratifications and exposure to public television. Communication Research, 6(2), 155–179. https:// doi.org/10.1177/009365027900600203 Palmgreen, P., & Rayburn, J. D. (1982). Gratifications sought and media exposure: An expectancy value model. Communication Research, 9(4), 561–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365082009004004 Panda, S., & Pandey, S. C. (2017). Binge-watching and college students: Motivations and outcomes. Young Consumers, 18(4), 425–438. https:// doi.org/10.1108/YC-07-2017-00707 Pappa, S., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., & Katsaounou, P. (2021). Author reply—Letter to the editor “The challenges of quantifying the psychological burden of COVID-19 on healthcare workers”. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 92, 209–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.11.025 Perks, L. G. (2015). Media marathoning: Immersions in morality. Lexington Books. Perks, L. G. (2019). Media marathoning and health coping. Communication Studies, 70(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2018.1519837 Pilkonis, P. A., Choi, S. W., Reise, S. P., Stover, A. M., Riley, W. T., & Cella, D. (2011). Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): Depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment, 18(3), 263– 283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111411667 Pittman, M., & Sheehan, K. (2015). Sprinting a media marathon: Uses and gratifications of binge-watching television through Netflix. First Monday, 20(10), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i10.6138 Pittman, M., & Steiner, E. (2021). Distinguishing feast-watching from cringe-watching: Planned, social, and attentive binge-watching predicts increased well-being and decreased regret. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(5), 1507–1524. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521999183 Potts, R., & Sanchez, D. (1994). Television viewing and depression: No news is good news. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 38(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838159409364247 Prestin, A., & Nabi, R. (2020). Media prescriptions: Exploring the therapeutic effects of entertainment media on stress relief, illness symptoms, and goal attainment. Journal of Communication, 70(2), 145–170. https:// doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa001 Primack, B. A., Swanier, B., Georgiopoulos, A. M., Land, S. R., & Fine, M. J. (2009). Association between media use in adolescence and depression in young adulthood: A longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(2), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry .2008.532 Rahman, K. T., & Arif, M. Z. U. (2021). Impacts of binge-watching on Netflix during the COVID-19 pandemic. South Asian Journal of Marketing, 2(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/sajm-05-2021-0070 Reinecke, L., Hartmann, T., & Eden, A. (2014). The guilty couch potato: The role of ego depletion in reducing recovery through media use. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 569–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12107 Reinecke, L., Klatt, J., & Krämer, N. C. (2011). Entertaining media use and the satisfaction of recovery needs: Recovery outcomes associated with the use of interactive and noninteractive entertaining media. Media Psychology, 14(2), 192–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2011.573466 9 Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye & C. C. Clogg (Eds.), Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419). Sage. Sender, K. (2012). The makeover: Reality television and reflexive audiences. New York University Press. Sigre-Leirós, V., Billieux, J., Mohr, C., Maurage, P., King, D. L., Schimmenti, A., & Flayelle, M. (2023). Binge-watching in times of COVID-19: A longitudinal examination of changes in affect and TV series consumption patterns during lockdown. Psychology of Popular Media, 12(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000390 Starosta, J., Izydorczyk, B., & Dobrowolska, M. (2020). Personality traits and motivation as factors associated with symptoms of problematic bingewatching. Sustainability, 12(14), Article 5810. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su12145810 Steiner, E., & Xu, K. (2020). Binge-watching motivates change: Uses and gratifications of streaming video viewers challenge traditional TV research. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 26(1), 82–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1354856517750365 Steins-Loeber, S., Reiter, T., Averbeck, H., Harbarth, L., & Brand, M. (2020). Binge-watching behaviour: The role of impulsivity and depressive symptoms. European Addiction Research, 26(3), 141–150. https://doi.org/ 10.1159/000506307 Sun, J.-J., & Chang, Y.-J. (2021). Associations of problematic bingewatching with depression, social interaction anxiety, and loneliness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), Article 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031168 Sung, Y. H., Kang, E. Y., & Lee, W. N. (2015, May). A bad habit for your health? An exploration of psychological factors for binge-watching behavior. 65th ICA Annual Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico. Tefertiller, A. C., & Maxwell, L. C. (2018). Depression, emotional states, and the experience of binge-watching narrative television. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 26(5), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2018 .1517765 Tukachinsky, R., & Eyal, K. (2018). The psychology of marathon television viewing: Antecedents and viewer involvement. Mass Communication and Society, 21(3), 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2017 .1422765 Vaterlaus, J. M., Spruance, L. A., Frantz, K., & Kruger, J. S. (2019). College student television binge watching: Conceptualization, gratifications, and perceived consequences. The Social Science Journal, 56(4), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2018.10.004 Wagner, B. E., Folk, A. L., Hahn, S. L., Barr-Anderson, D. J., Larson, N., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2021). Recreational screen time behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S.: A mixed-methods study among a diverse population-based sample of emerging adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), Article 4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094613 Wenner, L. A. (1986). Model specification and theoretical development in gratifications sought and obtained research: A comparison of discrepancy and transactional approaches. Communication Monographs, 53(2), 160– 179. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758609376134 Wolfers, L. N., & Schneider, F. M. (2021). Using media for coping: A scoping review. Communication Research, 48(8), 1210–1234. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0093650220939778 Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277(1), 55–64. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 Received July 13, 2022 Revision received April 6, 2023 Accepted May 17, 2023 ▪