Christian Morality: Sources & Modifiers of Human Acts

advertisement

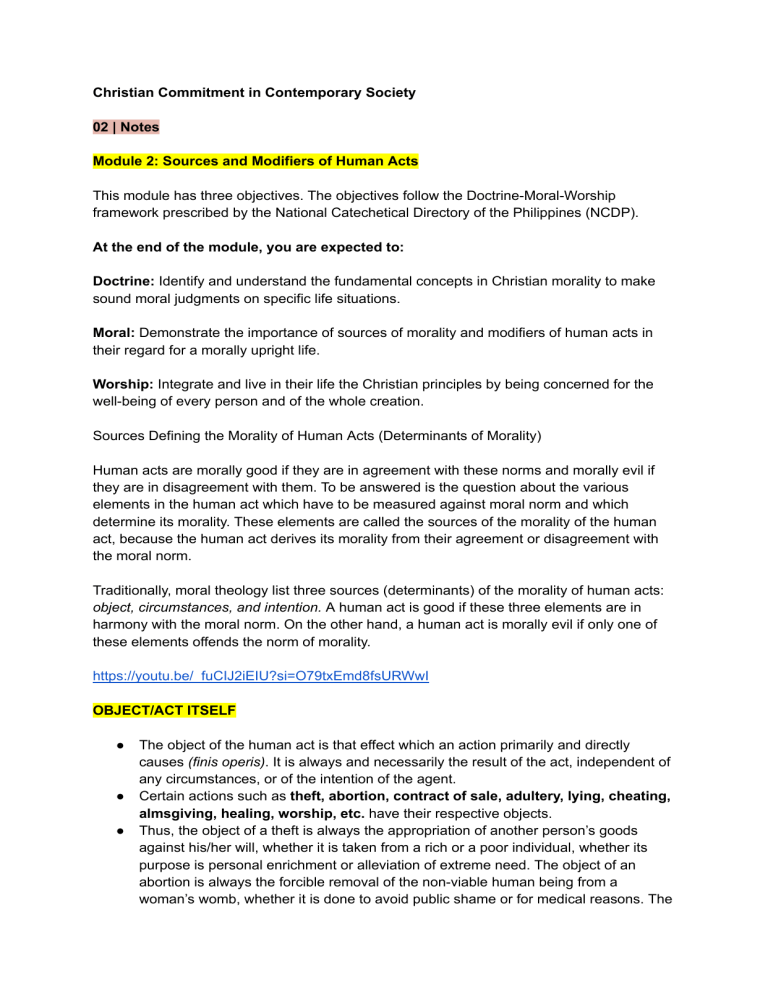

Christian Commitment in Contemporary Society 02 | Notes Module 2: Sources and Modifiers of Human Acts This module has three objectives. The objectives follow the Doctrine-Moral-Worship framework prescribed by the National Catechetical Directory of the Philippines (NCDP). At the end of the module, you are expected to: Doctrine: Identify and understand the fundamental concepts in Christian morality to make sound moral judgments on specific life situations. Moral: Demonstrate the importance of sources of morality and modifiers of human acts in their regard for a morally upright life. Worship: Integrate and live in their life the Christian principles by being concerned for the well-being of every person and of the whole creation. Sources Defining the Morality of Human Acts (Determinants of Morality) Human acts are morally good if they are in agreement with these norms and morally evil if they are in disagreement with them. To be answered is the question about the various elements in the human act which have to be measured against moral norm and which determine its morality. These elements are called the sources of the morality of the human act, because the human act derives its morality from their agreement or disagreement with the moral norm. Traditionally, moral theology list three sources (determinants) of the morality of human acts: object, circumstances, and intention. A human act is good if these three elements are in harmony with the moral norm. On the other hand, a human act is morally evil if only one of these elements offends the norm of morality. https://youtu.be/_fuCIJ2iEIU?si=O79txEmd8fsURWwI OBJECT/ACT ITSELF ● ● ● The object of the human act is that effect which an action primarily and directly causes (finis operis). It is always and necessarily the result of the act, independent of any circumstances, or of the intention of the agent. Certain actions such as theft, abortion, contract of sale, adultery, lying, cheating, almsgiving, healing, worship, etc. have their respective objects. Thus, the object of a theft is always the appropriation of another person’s goods against his/her will, whether it is taken from a rich or a poor individual, whether its purpose is personal enrichment or alleviation of extreme need. The object of an abortion is always the forcible removal of the non-viable human being from a woman’s womb, whether it is done to avoid public shame or for medical reasons. The object of the contract of sale is not only the physical transfer of goods from one place to another but also the exchange of property rights attached to the goods. ● ● The object is generally regarded as the primary source for the judgment on the morality of an act. The most important aspect of an action seems to be the immediate effect of which the action inevitably brings about in the objective order, independent of the intention of the agent and other circumstances. Catholic moral handbooks universally hold that the object of a human act can be morally good, evil, or indifferent. Indifferent from the viewpoint of the object are walking and playing an instrument, for example, but this does not mean that the entire action is morally indifferent for its morality further depends on the circumstances and particularly on the intention of the agent. The circumstances and the intention also further modify the morality of an action with a morally good object, even to the extent of making the action in its totality evil. Therefore, where the object of the human act is morally evil, as in a case of rape or murder, no purpose and intention of the agent—be it ever so good—can permit this act. https://youtu.be/UvnBaDNleEE?si=rBC0-8DqZQZSiIeq CIRCUMSTANCES - Circumstances are conditions outside the act (not part of the act) that influence or affect the act by increasing or lessening its voluntariness or freedom, and, thus affecting the morality of the act. In other words, Circumstances increase the goodness or badness of an act. These circumstances are: 1. The Circumstance of Person (it answers the question WHO?) refers to the DOER (agent) of the act and to the RECEIVER or the person to whom the act is done. There are two principles under this circumstance. A. A good act can become better, or a bad act can become worse by the reason of the doer or the person doing the act. For example, an act of giving aid to orphans is good, but if it is done by a street sweeper (who is poor himself/herself), the act becomes better or more meritorious than if it is done by a big-time businessman who earns millions of pesos a week Similarly, abortion is bad, but it becomes worse when the one who undergoes it is a nun or a member of a religious order who accidentally gets pregnant, than an ordinary woman. B. A good act can become better, or a bad act can become worse by the reason of the person to whom the act is done. Stealing is bad, but it is worse if one steals from a beggar than if he/she steals from a rich person. Murder is bad, but it is worse if one kills the Pope or the President of the country (by virtue of the positions they are holding) than if one murders an ordinary person or a criminal. 2. The Circumstance of Place (Where?) refers to the particular space or locality where the act is done or performed. Creating scandal is bad, but it is worse when it is done inside the church than if it is done outside the church. 3. The Circumstance of Time (When?) refers to the exact or definite moment or hour when the act is performed. Just like in the case of the other circumstances, a good act becomes better, or a bad act becomes worse by reason of the time when the act is performed. Stealing is bad, but it is worse if one steals during a curfew. Fasting in order to mortify oneself is good in itself, but it is better if one fasts during the designated time or day. (e.g. Ash Wednesday or Good Friday). 4. The Circumstance of Manner (How?) refers to the way the agent manages to do his/her act. It answers the question, “How did the agent do the act?” For example, a young man manages to have a sexual relationship with a young woman who is not his wife by making her believe in his false promise of marriage. 5. The Condition of the Agent answers the questions “Why? Or in what condition was the agent when he/she performed the act?” And “was the agent ignorant or influenced by fear, habits, emotions, etc.? Failure to attend Mass on a Sunday is bad in itself, but if a person is invisibly ignorant that it is Sunday and fails to attend Mass, there is no sin committed. 6. The Circumstance of the Thing Itself (What?) denotes the special quality of the object, e.g. the money stolen is one million pesos, the object is a famous religious icon, or a relic (like the crown of Sto. Niño), or the object desecrated is the statue of Rizal. 7. The Means answers the questions, “By What Means?” And “By Whose Help?” For example, a person robs a bank with the help of the bank’s security personnel (an inside job robbery). Intention Intention of the agent refers to the GOAL which the agent aims to achieve through his/her act. It is also the reason or the purpose why the agent aims to achieve through his/her act. It is also the REASON or the PURPOSE why the agent does the act. It is the movement of the WILL toward the end. The agent’s goal, purpose, or end —whether good or bad—has tremendous influence or effect on the morality of the act. There are some principles to consider regarding the intention of the agent. 1. An act which is good in itself and is done for a good end becomes doubly good. This principle means that an agent who performs a good act for a good purpose receives merits for the good act and another set of merits for his/her good purpose or intention. For instance, a rich person gives donations to the poor and the needy members of the community. His/her intention is simply to relieve (at least temporarily) these less fortunate people of their misery, inconvenience, and other consequences of poverty. This rich person’s act (giving donations) is already good in itself, so he/she merits this act. Likewise, his/her intention or purpose of giving such donations (to give relief) is good. Thus, he/she receives another set of merits for this good end. 2. An act which is bad in itself and is done with a bad end becomes doubly bad. This principle implies that an agent who performs a bad act because he/she wants to achieve a bad end, or has a bad intention, is liable or responsible on two counts. He/She is liable for the bad act, and is also responsible for the bad intention of doing the act. For example, a man rapes a girl for revenge. In this case, the act (raping) is bad in itself. The purpose or intention of the agent is the exact vengeance, which is also bad. Therefore, the man is responsible for the act of raping and for his bad intention. 3. An act which is good in itself and is done with a bad intention becomes bad. This principle demonstrates the strong influence of the end of the agent upon the morality of an act. The act is already good in itself, but due to the bad purpose or intention of the act, it becomes bad For example: A manager of a business form increases by 100% the monthly salary of his secretary. The manager does this so that his secretary cannot turn him down when he asks her to spend a night with him. The manager’s act of increasing the secretary's salary is undoubtedly and unquestionably good, but his purpose or intention for doing such a good act is bad. Hence, the act also becomes bad. The manager is not to be blamed for the bad intention alone but also for the act which is used as a means to attain a bad end. 4. An act which is bad in itself and is done with a good end does not become good. In other words, no good end can change a bad act into something for the simple reason that the end cannot justify the means. Here is a case to illustrate this principle: A father steals money because he wants to gift his son with a wristwatch for the latter’s birthday. We understand the good intention of the father to please his son. However, the means employed by the father to attain his goal is bad. Moral science cannot condone such act. In other words, the father’s act (stealing) used as a means toward an end is bad and unacceptable. However, while a good end cannot change a bad act into something good, it can free the agent from his/her responsibility or at least lessen or decrease the agent’s culpability. Two examples can demonstrate these points: ● ● A young woman is chased by a serial rapist. The young woman is cornered at the dead end of the street. Her only way to escape from the hands of the serial rapist is to kill him. So, the young woman kills the serial rapist by shooting him with her gun which she carries in her bag. It is very clear that at first, the young woman does not have any intention to kill the serial rapist. If ever the young woman has killed her attacker, it is because she has no other means of escaping from him since she is already cornered at the dead end of the street. Although the young woman’s act (killing/homicide) is in itself bad, she is free from any responsibility due to the fact that her purpose in killing the attacker is to protect her own life to which she has the right. A cashier of a certain department store steals money from the cash register to enable her to take her ailing mother to the hospital. The act of the cashier is bad, but her intention or purpose is good. While the cashier is still responsible for her act, the responsibility is lessened because of her good intention. 5. An indifferent act which is done for a good end becomes good. This principle agrees with the previous statement that an indifferent act becomes good or bad according to the end of the agent and the circumstance. There are acts whose very nature neither agree nor disagree with human reason. These acts become good or bad according to the goal or purpose in performing them. For example, the act of writing is indifferent. If one writes to explain an issue or doctrine so that many will be informed and enlightened on the matter, his/her purpose of writing is good. Hence, the indifferent act of writing becomes also good. 6. An indifferent act which is done for a bad end becomes bad. Talking is neither good nor bad. But if one talks to destroy the good name or reputation of another, the act of talking becomes bad. From the three sources defining the morality of human acts, namely, object circumstance, and intention, FIVE PRINCIPLES for judging the morality of human acts can be derived: 1. An act is morally good if the act itself, the purpose, and the circumstance are substantially good. 2. If an act itself is intrinsically evil, the act is not morally allowable regardless of the intention or circumstance. 3. If an act itself is morally good or at least indifferent, its morality will be 4. Circumstance may create, mitigate, or aggravate sin. 5. If all three determinants of the morality of human acts (the act itself, purpose, and circumstance) are good, the act is good. If anyone element is evil, the act is evil. https://youtu.be/wDHTGe2fZGo?si=SMapsp_ba-zPr3Oi Sample Moral Analysis: Let us weight the Pharisees’ actions in the Gospel reading using what we have learned and decide whether Jesus was correct on His harsh criticisms on the said local religious authorities of His time? 1. Object/Act itself: Action: Pharisees’ WORSHIP and PREACHING of God. Is the ACT: GOOD, BAD OR INDIFFERENT? The ACTS are GOOD. 2. CIRCUMSTANCES: A. PERSON: DOER: PHARISEES - religious authorities that preached in public about God and interpret His Laws RECEIVER: ISRAELITES - mostly the uneducated people of Israel B. PLACE: Public Places or Preaching places in Israel C. TIME: Time of Jesus D. Manner: Pharisees were noticeably strict on following religious laws and they interpret the law harder that it should be, making it a burden to people’s shoulders. E. Condition of the Agent: Filled with PRIDE because they love taking the place of honor at banquets, wear ostentatious clothing, and encourage people to call them rabbi. F. THING ITSELF: Word of God/Scriptures How did Circumstance add or lessen the moral goodness of Preaching the Word of God? The moral Goodness of the ACT is LESSENED because they didn’t seem to practice what they preached and worst instead of helping the common people to get close to God, they made it so hard to follow His ways. 3. Intention: Base from the circumstances shown from the Gospel, we can sense that the obvious intention of most pharisees back in Jesus’ time was to boast about how well they know their laws, how knowledgeable they were, how strictly they are able to follow God’s laws and that people should acknowledge their authority. Good ACT + Bad Intention = Bad Final Conclusion: The Pharisees’ good religious action is not really good as it seems. Jesus is so correct in accusing them of false preaching. They were more after following the external parts of the laws and obeyed it with pride, but they missed the heavier things of drawing the people near God. If we read the Gospel further, you will find that Jesus elaborates on their hypocrisy. He tells the religious leaders appear clean on the outside, but they have neglected the inside. Therefore, their action, no matter how good it looks on the outside, is BAD. Modifiers of Human Acts There are certain factors which may affect any of the three constituents of voluntary human acts. These factors which may diminish one’s culpability are called modifiers of human acts, also known as obstacles affecting the voluntariness of human acts. The five modifiers of human acts are ignorance, fear, concupiscence or passion, violence, and habit. 1. Ignorance ● Ignorance is the lack or absence of knowledge of a person who is capable of knowing. The two types of ignorance are invincible ignorance and vincible ignorance. Invincible ignorance is a type of ignorance which cannot be dispelled, or knowledge that is lacking and cannot be acquired. The inability to dispel the ignorance or acquire the knowledge that is lacking may arise from various causes. Example: When you are in a foreign country and the speed limit is written in another alien language. Since, ignorance cannot be expelled or dispelled by due diligence and reasonable effort then the person is not responsible. ● ignorance which can and should be dispelled. It implies culpable negligence. The person could know and ought to know. Vincible ignorance can be cleared up if one is diligent enough. For instance, a person who knowingly violates safety and health protocols in a time of pandemic would be responsible for his/her actions. ● There are three kinds of vincible ignorance: simple vincible ignorance, crass or supine ignorance, and affected vincible ignorance. Simple vincible ignorance exists when one uses some, but not enough diligence, in an effort to remove the ignorance. It does not free us from responsibility. Suppose a nurse is unsure of dosage. She refers to the doctor’s order sheet and finds that she is unable to read the doctor’s handwriting. She knows that the doctor is at the office but does not bother to talk to the doctor. As she administers the medication, guessing at the dosage, she is guilty of simple vincible ignorance. ● Crass or supine ignorance is that which results from mere lack of effort. For instance, a doctor discovers in his patient certain symptoms which he does not recognize. On the shelf over his desk is a good medical book that could assist him to diagnose the symptoms. However, he does not bother due to laziness to read the medical book. ● Affected vincible ignorance is that which is deliberately fostered in order to avoid and obligation that knowledge might bring to light. For instance, a nurse who accepts employment with a doctor who frequently practices artificial insemination. The nurse may suspect that this is immoral or something which is contrary to the teaching of the Church but carefully avoids inquiring or even discussing the matter with anybody, lest the nurse discovers that he/she is cooperating in immorality and be obliged to leave his/her well-paying job. It is affected because she wants to be ignorant, and it is vincible because the nurse could dispel the ignorance easily. ● “Ignorance of the law” refers to a lack of knowledge that a particular law exists. Example: When a driver does not know that there is an 80 kilometer-per-hour speed limit for a particular road. ● “Ignorance of the fact” is a lack of realization that one is violating a law. Example: A driver knows that there is a 60 kilometer-per-hour speed limit but does not realize that he/she is travelling at 80 kph. ● There are two general moral principles concerning ignorance. First, invincible ignorance eliminates responsibility or culpability. Second, vincible ignorance does not eliminate moral responsibility but lessens it. The reason behind these two principles is that when one is invincibly ignorant, the act he/she does would then be without knowledge. Without knowledge, there can be no voluntariness, hence, no responsibility. No one can consent to violate a law which he/she does not know. In case of vincible ignorance, however, there is still culpability with regard to one’s ignorance which is due to one’s negligence or omission. Consequently, there is still accountability on the part of the parson for his/her action. The act of violating the law is still voluntary at least in cause, that is, indirectly voluntary. 2. Fear ● Fear is a mental agitation or disturbance of mind brought about by the apprehension of some present or imminent danger. ● Grave fear is that which is present when the evil threatening is considered as serious. Intrinsic grave fear is that agitation of the mind which arises because of a disposition within one’s body or mind. Example, the fear of cancer is intrinsic. On the other hand, extrinsic grave fear is the agitation of the mind which arises from something outside oneself. ● Slight fear is a type of fear in which the evil threatening is either present-but-slight or grave-but-remote. Example for present-but-slight fear: an elderly man experiences fear when he hears someone passing his door at night, but his fear is slight because he knows it is probably his neighbor arriving home at usual. Example for grave-but-remote fear: a man fears that he may die of cancer in his life, but his fear is slight because the grave danger is very remote. ● Moral principle of fear: Fear diminishes the voluntary nature of the act. A sinful act done because of fear is somewhat less free and therefore less sinful than an act done not under the influence of fear. 3. Concupiscence or Passion ● Concupiscence or passion is the movement of the sensitive (irrational) appetite which is produced by good or evil as apprehended by the mind. Concupiscence is not ● ● ● limited to sexual desire. Passions are strong tendencies towards the possession of something good or towards the avoidance of something evil. Movements of the passions are usually called feelings or emotions, especially if not vehement. Love, hatred, joy, grief, desire, aversion, hope, courage, fear, and anger fall under this heading. Passions may be considered good when ordered by the rational will to help a person in the practice of virtue or in the attainment of what is morally good. When passions are not controlled by reason, passions may become destructive and evil. They are considered bad when used by the rational will to accomplish morally evil acts, like using courage to rob a bank. A person has the urgent duty to control and check one’s sensitive appetites since the possibility to succumb to them is not remote. Karl Peschke remarks “that the whole process of moral education, both in the early and in the later years, is to a large extent a process of gaining command over all the movements of the passions. Thus, man/woman has to eventually become master of himself/herself.” There are two types of concupiscence; antecedent concupiscence and consequent concupiscence. Antecedent concupiscence precedes an act of the will and is not willfully stimulated, such as sudden anger. On the other hand, consequent concupiscence is that which is deliberate and stimulated by the will, such as anger deliberately fostered. Moral principles regarding concupiscence: Antecedent concupiscence lessens the voluntary nature of human acts and lessens the degree of moral responsibility accordingly. Consequent concupiscence does not lessen moral responsibility. Rather, a person acting with consequent concupiscence is completely responsible. 4. Violence ● Violence is an external force applied by someone on another in order to compel the person to perform an action against one’s will. ● There are two general types of violence, perfect and imperfect violence. In cases where the victim gives complete resistance, the violence is classified as perfect violence. If a woman walking a dark street at night is attacked and she attempts to fight of the attackers with all the physical powers at her command, she has been the victim of perfect violence. However, if the victim offers insufficient resistance, the violence is classified as imperfect violence. In other words, some resistance is shown but not as much as should be. An office secretary who is working after hours in an almost empty building is approached by the department head. The department head, suddenly filled with lustful intentions, makes certain rough and violent advances. The secretary for a moment puts up some resistance and feels that additional resistance might terminate the incident. However, the secretary quickly ceases resistance and gives in to the department head. ● Regarding perfect violence, the moral principle is that which is done from perfect violence is entirely involuntary, and so in such cases there is no moral responsibility. ● Regarding imperfect violence, the moral principle is that which is done under the influence of imperfect violence is less voluntary, and so the moral responsibility is lessened but not taken away completely. ● It is also important to take note that if an individual is a victim in the absolute sense of the word, no sensible person will condemn him/her. If a victim makes a judgment that resistance is utterly useless, he/she need not resist. There is no obligation to do what is useless. For instance, a bank cashier and two security guards are held up by ten heavily armed bank robbers. The cashier and the security guards know that no amount of resistance would be effective to stop the bank robbery. In this case, there is no obligation to resist because of the overwhelming threat to life of the robbery situation. 5. Habit ● A habit is an inclination to perform some particular action acquired by repetition and characterized by a decreased power of resistance and an increased facility of performance. It is also “a stable quality to a faculty positively inclining a person to act in a certain way.” A habit is often referred to as “second nature,” which means something is deeply embedded in an individual but ingrained by being acquired than being inborn. ● Habits may be good or evil as to whether they influence one to do good or evil. If a habit disposes a person to do good, it is called a virtue. However, if a habit disposes a person to de evil, it is called a vice. ● Moral considerations regarding habit: (1) Evil habits do not lessen the imputability of evil actions performed by force of habit, if the habit has been recognized as evil and is freely permitted to continue; (2) Evil habits lessen the imputability of evil actions performed by force of habit if one is sincerely trying to correct the habit. A habit does not destroy the voluntary nature of our acts. A person is at least, in some way, responsible for acts done from habit as long the habit is consciously allowed to endure.