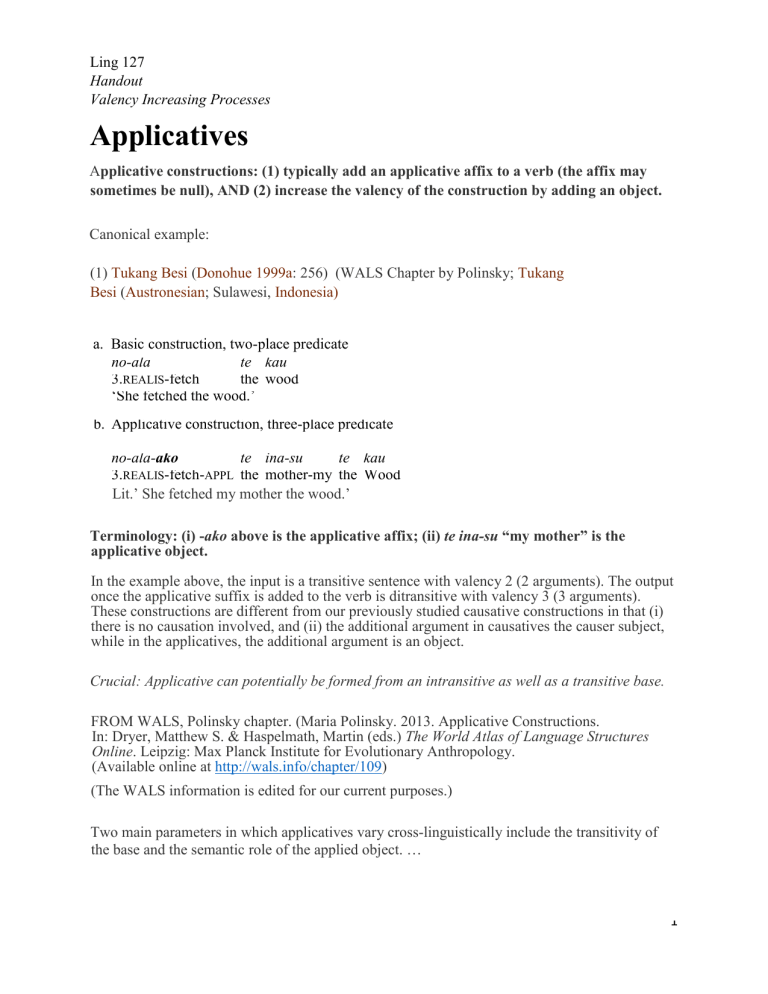

Ling 127 Handout Valency Increasing Processes Applicatives Applicative constructions: (1) typically add an applicative affix to a verb (the affix may sometimes be null), AND (2) increase the valency of the construction by adding an object. Canonical example: (1) Tukang Besi (Donohue 1999a: 256) (WALS Chapter by Polinsky; Tukang Besi (Austronesian; Sulawesi, Indonesia) a. Basic construction, two-place predicate no-ala te kau 3.REALIS-fetch the wood ‘She fetched the wood.’ b. Applicative construction, three-place predicate no-ala-ako te ina-su te kau 3.REALIS-fetch-APPL the mother-my the Wood Lit.’ She fetched my mother the wood.’ Terminology: (i) -ako above is the applicative affix; (ii) te ina-su “my mother” is the applicative object. In the example above, the input is a transitive sentence with valency 2 (2 arguments). The output once the applicative suffix is added to the verb is ditransitive with valency 3 (3 arguments). These constructions are different from our previously studied causative constructions in that (i) there is no causation involved, and (ii) the additional argument in causatives the causer subject, while in the applicatives, the additional argument is an object. Crucial: Applicative can potentially be formed from an intransitive as well as a transitive base. FROM WALS, Polinsky chapter. (Maria Polinsky. 2013. Applicative Constructions. In: Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.) The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. (Available online at http://wals.info/chapter/109) (The WALS information is edited for our current purposes.) Two main parameters in which applicatives vary cross-linguistically include the transitivity of the base and the semantic role of the applied object. … 1 TWO typological distinctions: (1) “With respect to the transitivity of the base, the main distinctions are between applicatives formed (i) from a transitive base only, (ii) from an intransitive base only, and (iii) from both bases. (2) With respect to the semantic roles of the applied object, the most common role of the applied object is that of benefactive. Accordingly, the values differentiates applicatives whose applied object (i) is limited to benefactive; (ii) corresponds to the benefactive and some other roles; (iii) corresponds to other roles to the exclusion of the benefactive. Of nine logically possible values…, seven are actually attested. In addition, there are of course many languages are without applicatives. VALUES: Value Representation Benefactive object only; both bases 16 Benefactive object only; transitive base only 4 Benefactive and other; both bases 49 Benefactive and other; transitive base only 2 Non-benefactive object only; both bases 9 Non-benefactive object only; transitive base only 1 Non-benefactive object only; intransitive base only 2 No applicative construction 100 Total: 183 So, of the 83 languages that have applicatives in the data, 49 allow (i) both applicatives of transitives and intransitives. Other possible types are less common. (WALS) Other semantic roles The distribution of applicatives with respect to the semantic role benefactive is clearly the most common semantic role of the applied object. Other common semantic roles include location and instrument. The geographical distribution of these roles is shown below: 2 Values: Other Roles of Applied Objects Value Representation Instrument 17 Locative 18 Instrument and locative 12 No other roles (= Only benefactive) 36 No applicative construction 100 Total: 183 Additional semantic functions that may be associated with the applied object include possessor, circumstance/event (time), comitative, and substitute (a participant on whose behalf the action is performed). (also location/goal as below) • In some languages, the applied suffix varies according to the semantic role of the argument introduced: Kinyarwanda (Bantu; Rwanda) Goal: (1) a. umugore y-ooher-eje umubooyi ku-isoko woman 3SG-send -ASP cook LOC-market “The woman sent the cook to the market.” b. umugore y- ooher-eke -ho isoko woman 3SG-send -ASP-APPL market umubooyi cook “The woman sent to the market the cook” Instrument: (2) a. umugabo ya- tem-eje igiti n-umupaanga man 3SG-cut -ASP tree INSTR-saw “The man cut the tree with a saw.” b. umugabo ya- tem-ej -eesha umupaanga igiti man 3SG-cut -ASP-APPL saw tree “The man cut the tree with a saw.” 3 WALS “Comitative applicatives formed from intransitives seem to be particularly common in the languages of Australia. Comitatives and substitutives are quite common in applicatives of intransitives, e.g. in Lai (2) and in Kinyarwanda (3): (2) Lai (Peterson 1999: 58) ʔa-ka-Than-pii 3SG.SUBJ-1SG.OBJ-grow_up-APPL.COM ‘He grew up with me.’ [comitative] (3) Kinyarwanda (Polinsky) umugabo a-ra-geend-er-a umugóre man 3SG-PRES-travel-APPL-ASP woman ‘The man is travelling instead/on behalf of the woman.’ [substitute] It is somewhat puzzling that some languages of Australia show a comitative applicative formed from an intransitive without a parallel benefactive applicative formed from a transitive. Such comitative applicatives may be marked by the same morphology as instrumental applicatives formed from transitives. It is possible that these Australian-type applicatives and applicatives elsewhere represent different phenomena. WALS: Transitivity of the base The intransitive base of applicatives is less common than the transitive base. This is quite clear from the distribution shown above, and there are only two languages in the sample that form applicatives from the intransitive base exclusively (Fijian, Wambaya). Implicational Universal: If a language has applicatives formed from the intransitive base, it generally also has applicatives formed from the transitive base. Although the constraint on applicative formation from intransitives seems not to be absolute, a particular subset of intransitives, namely unaccusative predicates (those whose subject originates as an object in the underlying structure), resist applicativization (see Baker 1998). However, even this generalization does not hold in some languages, for instance, in Halkomelem (Gerdts 1988a), Lai (Peterson 1999), and Sesotho (Machobane 1989), which suggests that it is just a strong tendency. WALS: Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Applicatives: “In some languages both objects, basic and applied, are accessible for passivization and relativization, can bind a reflexive, can trigger agreement on the verb, or can license coreferential deletion across clauses. Such languages are called “symmetrical”. In other languages, only one object, either applied or basic, can show the relevant grammatical behaviors, while the other object is syntactically quite inert. Such languages are called “asymmetrical” (Woolford 1993; Alsina and Mchombo 1993). The asymmetrical type seems to be more common.” 4