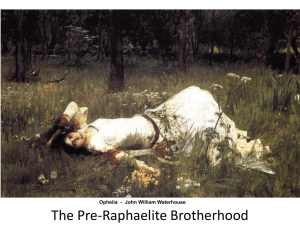

Pygmalion and Galatea: Androgyny in the Pre-Raphaelite Ideal by Hannah Hadley Fall 2017: ARTH-X 491 Professor: Bret Rothstein In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, he tells the story of Pygmalion, an artist who created a statue of a woman so beautiful and life-like it came alive. The Pygmalion myth, the artistic pursuit of a life-like image, was referenced by a group of artists in the eighteenth century, by the name of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, collectivized by an obsession with Ovid, the classics, and Renaissance Art. These artists began to openly challenge the contemporary visual conventions of human representation especially in regards to the female body. Through a new romantic, aesthetics, and often ambiguous and androgynous visual language, these artists pursued the “pygmalion” aims. Contemporary criticism chastised the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood repeatedly for their ugly, maimed, and deformed images of the human body.1 There was something different the Pre-Raphaelites did in their depictions of age old stories that set contemporaries on edge, and although there have been many studies on the implications of the female figures played with in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, only some writing has chosen to speak about the androgyny of many of the figures. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was compiled of a complex network of artists, each with their own motivations in creating art, in this study, it is not my intention to argue an androgynous style was created intentionally by any of them, but within the PreRaphaelite circle, a visual connection can be made in regards to their pursuit of the ideal image and an innovation towards the mixing of gendered attributes to create their ideal. While Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) set the stage for a new ideal, evidence of androgyny can be found many Pre-Raphaelite works such as Simeon Solomon, but can be seen most clearly in Edward Burne-Jones’(1833–1898) later work as he dealt with matters of fear and desire within the confused binary of female and male bodies. 1 J. B. Bullen, The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire In Painting, Poetry, and Criticism. (Oxford: Clarendon 1 The concept of an androgyne is one of the most ancient in western civilization; the Platonic myth of Aristophanes describes the third2 type of primordial human as a cosmic androgyne who was split and cast into the world in two conflicting heterosexual parts, cursed to forever seek their other male or female half.3 This myth, in the late nineteenth century, inspired many artists and writers to think about beauty and gender differently. Bram Dijkstra argues in his article, “The Androgyne in Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature,” that many unconventional male artists became fascinated with the ideal of an androgyne, a person with the physical characteristics of both sexes, because of their desire to escape the polarization of males and females in bourgeois society. They saw an androgynous ideal as the balance between feminine and masculine parts of human nature.4 Dijkstra’s argument was made upon greater observation of the western art and writing movement as a whole, but in Britain, the small artist group of the Pre-Raphaelites naturally became attracted to these ideas and began creating a new kind of human ideal. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood formed in the 1840s through the friendships of William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti during their studies at the Royal Academy Schools. In the academy, they were schooled in the artistic theory of Sir Joshua Reynolds. The young Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood took to creating pieces inspired from art of the past masters, but they rejected the beloved Victorian mannerist style based in Raphaelite ideals taught by Reynolds and instead sought inspiration from a pre Raphael period.5 From the beginning of the movement, the Pre-Raphaelites incited hostile responses from their 2 The first two types of primordial beings were said to be all female and all male, when they were split they also sought their other halfs, like the androgyne, thus explaining the cosmic origins of homosexuality. 3 Plato, and Avi Sharon, Plato's Symposium, Newburyport, MA: Focus Pub./R. Pullins Co., 1998. 4 Bram Dijkstra, "The Androgyne in Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature," Comparative Literature 26, no. 1 (1974): 62. 5 Malcolm Warner, “The Pre-Raphaelites and the National Gallery,” in Pre-Raphaelite Art In Its European Context, Madison, Susan P. Casteras, and Alicia Craig Faxon[N.J.]: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994, 1. 2 contemporaries in regards to their representation of the human body, forming the first avantgarde movement in British painting.6 Their works stretched the boundaries of the bourgeois by depicting unconventional female bodies and settings, in a time period notorious for its preemptive counter movements blocking a push towards sexual liberation.7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti has been credited as the most advanced artist in fusing the “aesthetic” and the “sexual.”8 He was one of the most central figures in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, mentoring and inspiring most of the other members with his passion for beauty, subversive style, and skill with a pen. Before the Pre-Raphaelite name was formed, Rossetti choose the label “Art Catholic” for his work. Although Rossetti’s work dealt with spirituality and virtue intensely, he was never a believing Catholic.9 In Ecce Ancilla Domini (Latin: "Behold the handmaiden of the Lord"), Rossetti depicts the subject of the Virgin Mary as the angel foretells of Christ’s miraculous birth. In Rossetti’s version of the annunciation, the sexless angel Gabriel holds a lilly towards Mary as she stares at it blankly. The Lilly, a commonly known symbol of innocence, purity, and beauty, has been payed special attention to highlight its perfection in Ecce Ancilla Domini (1850). Not only does this painting show Rossetti’s fascination with perfection through spiritualism, but also reveals his own anxiety as an artist in Mary’s expression. Because he was primarily only aesthetically attracted to religion, his sentiments as an “Art-Catholic” were not long lived when his aesthetic tastes evolved.10 Rossetti’s interest in spirituality is key to understanding the fear and desire that fueled later works forming the “fleshly school of painting” in the Pre-Raphaelite movement. 6 J. B. Bullen, The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire In Painting, Poetry, and Criticism, 1-2. Karen Harvey, "The Century of Sex? Gender, Bodies, and Sexuality in the Long Eighteenth Century." The Historical Journal 45, no. 4 (2002): 899. 8 Martin A. Danahay, "Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Virtual Bodies." Victorian Poetry 36, no. 4 (1998): 379. 9 David G. Riede, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Limits of Victorian Vision, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983, 19. 10 Ibid, 53. 7 3 In Ovid, Pygmalion is frustrated by the lack of virtue found in the women of his world, which inspires him to create the ultimate ideal: He made, with marvelous art, an ivory statue, As white as snow, and gave it greater beauty Than any girl could have, and fell in love With his own workmanship. The image seemed That of a virgin, truly, almost living, And willing, save that modesty prevented, To take on movement.11 A virgin made of ivory, perfect in every way except for her lack of real human flesh. Even in this story, perfection is only achieved through a spiritual means. Once Galeta comes to life, her sexual nature is fully realized and the innocent courtship Pygmalion play-acted becomes one of fleshly desires realized: Back where the maiden lay, and lay beside her, And kissed her, and she seemed to glow, and kissed her, And stroked her breast, and felt the ivory soften12 The innocence of Rossetti’s style and taste were soon overturned for a wholehearted obsession with the “fallen woman” or the “sexualized woman.”13 Bocca baciata (Fig. 2), a painting that caused much controversy in 1859 had procured its name from a story about the daughter of a Babylonian Sultan who was betrothed to the King of Algarve, but on her way to her betrothed, she becomes the mistress and conquest for a long series of men. After much effort she finally makes her way back home to convince her father that she was in a Christian convent during her time away.14 She is then reberothed to the Algarve king under the guise of her virginity and marries him at last. On the back of the painting Rossetti inscribed the concluding lines of the story which translates to “A kissed mouth doesn’t lose its freshness, for like the moon it always 11 Ovid and Rolfe Humphries, Metamorphoses, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983, 241-242. Ibid, 242. 13 J. B. Bullen, The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire In Painting, Poetry, and Criticism, 49. 14 Ibid, 91. 12 4 renews itself.”15 The figure in the painting was critiqued for its licentiousness by William Holman Hunt and compared to “foreign prints” or pornography. Hunt said of it, “Rossetti is advocating as a principle mere gratification of the eye and if any passion at all–the animal passion to be the aim of art.”16 Rossetti sought to celebrate this gratification of the eye, but many were shocked by the errotic nature of such a portrait. The figure was seen as a foreign pornographic print because its sensuality felt to viewers so otherworldly and unknown. Her body features are a mix of feminine in the lips, hair and hands, but otherwise very masculine in the neck, nose, and face. Throughout his career, he challenged viewers with these types of sensuous portraits of beautiful masculine-looking women, seeking with every painting to gratify the eye and play into passion. His work played a major role in pushing the artists in the Pre-Raphaelite group to stretch the boundaries of what could be considered beautiful when it came to the human body and forming their mythic ideal. Much of what we know of the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic comes from Rossetti’s images of females where woman represents fantasy and masculine desire. A lesser known Pre-Raphaelite artist and contemporary to both Rossetti and Burne-Jones, Simeon Solomon, chose instead to focus on primarily male figures.17 Solomon was thought of as a prodigy in his early years at the academy with a wayward genius and mysticism likened to William Blake. His success as an artist began to spiral downward in 1873 after a broken engagement to a beautiful woman during the peak of his fame, until eventually he was found dying on the street by a police officer in 1905.18 His legacy is relevant because of the ways his style kept all of the ambiguity of Rossetti’s 15 J. B. Bullen, The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire In Painting, Poetry, and Criticism, 89-91. Ibid, 94. 17 Colin Cruise, “‘Lovely devils’: Simeon Solomon and Pre-Raphaelite masculinity,” In Re-Framing the PreRaphaelites: Historical and Theoretical Essays, Edited by Ellen Harding, Aldershot, England: Scolar Press, 1996, 195. 18 Leulla M. Wilson, "Simeon Solomon—A Dreamer of Dreams," Fine Arts Journal 25, no. 3 (1911): 165. 16 5 style in its remoteness of gaze, distorted facial features, and emotionality, but translated into the male body.19 Cruise stated, “Solomon’s paintings present the viewer with a puzzle, however, for while the subject appears to be male, bears a male name and is dressed as a man, the facial features are ambiguous.” In 1867 Solomon completed the oil painting Bacchus (Fig. 3), where these attributes are in play. Like Rossetti, Solomon focus of the painting is on the face, in which generalized beauty is driven from Leonardo, Titian and Botticelli.20 The figure lacks an exact expression, giving it an air of sensualized ambiguity common in Rossetti’s paintings. Although the commentary on this painting by the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery’s website is perhaps too reductive, that “Solomon's often sensual images of men, of which this is a good example, can be linked with his own homosexuality,”21 many have argued for this interpretation. Regardless, Solomon’s depictions of the male body show that Rossetti’s style was not only considered sexual because of his female subject, but that the very nature of how the PreRaphaelites morphed ambiguity within a gendered binary made them sexualized. Edward Burne-Jones is one of the most important artists in showing this dynamic, not only because of his long career, but because of his interest in depicting both male and female bodies equally. Burne-Jone was born in Birmingham, England in 1833. His mother died from complications in childbirth when he was just six days old, and his father, blaming him for his mother’s death, withdrew from giving parental love to him during his childhood.22 He attended the Birmingham School of Art from 1848-52, but later switched interest and enrolled in Exeter College at Oxford to study theology and the classics. It was at Oxford that Burne-Jones met William Morris, another principle artist within the Pre-Raphaelite circle, who also had a passion 19 Colin Cruise, “‘Lovely devils’: Simeon Solomon and Pre-Raphaelite masculinity,” 195. Ibid, 198. 21 http://www.bmagic.org.uk/objects/1961P52 22 Liana Cheney, Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings: The Pygmalion of the Pre-Raphaelite Painters. New York: Peter Lang, 2014, xxix. 20 6 for theology and the classics. At Oxford, they studied Ovid’s Metamorphoses for the first time and met many other future Pre-Raphaelites who shared in their interest of the middle ages and antiquity.23 Burne-Jones and Morris were also admirers of religion like Rossetti, pursuing a clergyman's career for a short time during their studies at Oxford, but later withdrawing for theological and political reasons. After seeing the work of Rossetti for the first time in 1854, Burne-Jones went to London to introduce himself in 1856 and subsequently became Rossetti’s student and friend.24 Burne-Jones was familiar with the art of Botticelli, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Titian, and the Mannerist painters from his multiple trips to Italy throughout 1859–73.25 Within the Pre-Raphaelite group, Burne-Jones stands out in his self-conscious alignment with the theories of the mannerist style.26 He spoke openly of his love for Renaissance mentors Botticelli and Michelangelo and the power of the beauty experienced viewing their paintings.27 His artistic pursuit in his own words states, “only this is true, that beauty is very beautiful, and softens, and comforts, and inspires, and rouses, and lifts up, and never fails.”28 Although he borrowed formal elements from these masters, his work with the human body was heavily influenced by Rossetti, his unhappy marriage to painter Georgiana MacDonald, and his affair with Greek sculptress Maria Cassavetti Zambaco, that filled his work with elements of mystery and queerness that only became stronger throughout his career. Within Burne-Jones’ work there is a persistent duality as he constantly depicted both male and female subjects of myth or legend side by side within the frame. Phyllis and Demophoon (Fig. 4) was displayed at the Old Watercolour Society for the Summer Exhibition of 23 Liana Cheney, Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings, xxix-xxx. Joseph Kestner, "Edward Burne-Jones and Nineteenth-Century Fear of Women," Biography 7, no. 2 (1984): 97. 25 Liana Cheney, Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings, xxix-xxx. 26 Ibid, 23. 27 Ibid, 8. 28 Ibid, xxv. 24 7 1870, but Burne-Jones choose to withdraw the painting only after only two weeks because of complaints. This painting was one of significance in his affair with Maria Cassavetti Zambaco, who he modeled both Phyllis and Demophoon off of. He expressed feelings of loss and desire through depicting tragic love sagas, during and after their relationship. A quote from contemporary Justin McCarthy states very well the confusing male-female dynamic coined by Burne-Jones that is evident in Phyllis and Demophoon: “Her lover is always singularly like herself. . very much the same-sort of thing. The hero has gaunt face, the red hair; he is almost invariably the dress I doubt whether you would know one from the other.”29 Burne-Jones cites Ovid’s second Heroides and Chaucer’s Legends of a Good Woman as the source for the ancient story that inspired the painting Phyllis and Demophoon.30 In the story, heartbroken Phyllis commits suicide when her lover, son of Theseus, delays in his return to her. She is turned into an almond tree by the gods after hanging herself and when Demophoon finally returns, he embraces the tree and it blooms releasing Phyllis back into the arms of her faithless lover.31 The slender, curve less forms of the figures confused and offended viewers, but later Burne-Jones made another version transforming the bodies into a tribute to Michelangelo, titling it Tree of Forgiveness (1881-82),32 praising Michelangelo for knowing “how to symbolize mystery.” Burne-Jones and Maria Zambaco had a rumored suicide pact to drown themselves in the Serpentine which was attempted in 1869 by Zambaco when Burne-Jones tried to leave her.33 This painting seems to be a way Burne-Jones reconciled these traumas within the relationship as well as shows a longing for a union of female and male forms. By making the male and female 29 Joseph Kestner, "Edward Burne-Jones and Nineteenth-Century Fear of Women," 96. Liana Cheney, Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings, 32. 31 Ibid, 31-32. 32 Ibid. 33 Joseph Kestner, "Edward Burne-Jones and Nineteenth-Century Fear of Women," 101. 30 8 bodies less distinguishable entities Burne-Jones is attempting to call back a time of cosmic perfection spoken of by Plato in the Symposium. In 1875, Burne Jones received a commission from Arthur Balfour to create a series on Perseus, unfortunately, only four of the eight selected episodes were finished by the time of his death: The Baleful Head (1887), The Rock of Doom and The Doom Fulfilled (Fig. 5, 1888), and Perseus and the Graiae (1892). The Calling of Perseus, Perseus and the Sea Nymphs, The Finding of Medusa, and The Death of Medusa can be seen in drafts, but were never finished.34 Each painting in the completed series showcases the male body of Perseus balanced by a female body. Kurt Lôcher notes that in the Perseus "all the figures appear to be of same sex: slender, delicate, and ageless," which points to a fear of sexuality in Burne-Jones.35 Kestern, the author of Edward Burne-Jones and Nineteenth-Century Fear of Women, argues that Burne-Jones may be obscuring or eliminating male genitalia in his paintings because of a childhood memory pointing towards his fear of castration.36 His argument, however, like many others made about the PreRaphaelites seems to be a bit reductive. In the earlier version of Perseus and Andromeda (Fig. 6), Perseus’s genitals are obscured on the left and covered completely by the serpent in the depiction on the right. Andromeda’s features as well are not defined clearly, but as woman, she is the assigned symbol of idealized beauty. She posture in both poses, the contrapposto of her nude body, suggest a heightened air of perfection that in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Andromeda is described to have: And when Perseus saw her there, Andromeda Bound by the arms to the rough rocks; her hair Stirred in a gentle breeze, and her warm tears flowing Proved her not marble, as he thought, but woman. 34 Joseph Kestner, "Edward Burne-Jones and Nineteenth-Century Fear of Women," 111. Ibid, 112-113. 36 Ibid, 113. 35 9 Perceiving her as so beautiful to be a statue, Perseus falls in love when he realizes her flesh is real. This is a type of inverse of the Pygmalion story, where flesh is so beautiful it is mistaken for stone, that Burne-Jones’ figures perfect as they morph into each other creating beautiful ideals. The piece that truly shows the relational shift of the Galatian image to that of an androgyne, is Burne-Jones literal depiction of the Pygmalion series, completed in the year 186870, and again in the year 1875–78. The series originated from a collection of drawings he did for William Morris’ Earthly Paradise of 1868, a book of classic and romantic tales told through a medieval lense.37 Cheney said of this, “Burne-Jones’ legend likewise evokes a medieval atmosphere associated with courtly love rather than with classical legend, although drawing inspiration from the maniera aesthetic and using the maniera figure type.”38 In the first painting, The Heart Desires (Fig. 7a), there is a depiction of Pygmalion alone in his studio pondering what he will make, while female onlookers gaze at him through his doorway. Pygmalion's pose and long robe hide any artifact of gender as he stands in front of three statues of female nudes. Here, Pygmalion is shown in celibacy and frustration with the women of his time, waiting for his ideal, before to trying to create it for himself. In The Hand Refrains (Fig. 7b) Pygmalion is shown gazing thoughtfully at his created Galatea, whose face mirrors his in features and whose body is painted smooth and soft. The Godhead Fires (Fig. 7c) shows Galatea coming to life reaching out for the goddess Venus. Galatea looks very masculine in this painting, even though she is still nude, her arm is just barely leaving the smallest peak of breast visible and her neck straining out towards the goddess is thick and masculine. The posse creates a direct correlation with BurneJones’ last piece in the series The Soul Attains (Fig. 7d), where Pygmalion is straining his neck 37 38 Liana Cheney, Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings, 24. Ibid. 10 out towards his awakened masterpiece. In profile, it is clear Burne-Jones uses the same form to create the neck and face of the two subjects. He plays with the aesthetic beauty of creating a union of form between the two figures as it speaks to his love of love. Liana Cheney, in Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings, states “The [Pygmalion] story as illustrated by Burne-Jones emphasizes the power of creativity over unformed matter, the power of the image over nature.”39 This aesthetic union of male and female, nature and spiritual, longing and fulfillment, is at the core of what Burne-Jones was dealing with when creating his ideal and why he stands out among the Pre-Raphaelite artist. Although humanity will never escape from the binary of male and female bodies, what the Pre-Raphaelites did was reveal the sensuousness of ambiguity. What contemporaries thought to be inappropriate and shocking,40 was really a play on human desires to be unified with their other half.41 The Pre-Raphaelites had an extreme love of beauty and therefore were willing to stretch accepted forms to make room for deeper and more mysterious idealized forms of beauty within depictions of male and female bodies. Gabriel Dante Rossetti, Simeon Solomon, and Edward Burne-Jones, were the catalyst for a huge shift in the artistic pursuit of a life-like image, where emotion, ambiguity, and historical reference all aligned to create the “perfect” idealized image instead of simply a realistic human form. The Pre-Raphaelites learned new ways of gratifying the eye to please or intrigue the viewer to look at age-old subjects anew. It is unclear whether this ernest quest for the perfection of the human figure in aestheticism has lead more artist than the Pre-Raphaelites back to an androgynous ideal, but the push towards androgyny has 39 Liana Cheney, Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings, 28. J. B. Bullen, The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire In Painting, Poetry, and Criticism, 6-7. 41 The Platonic myth makes room for explanations of homo and hetero sexuality. 40 11 been documented throughout the nineteenth century as “the central symbol of revolt.”42 Many Pre-Raphaelite scholars have touched on this subject, such as Susan Casteras, Liana Cheney, Colin Cruise, and Joseph Kestner, but none have talked in length about androgyny within the whole movement. Choosing to focus only on the “fallen woman” and her implications within the Pre-Raphaelite’s work, may be oversimplifying the greater issue of gender found in Rossetti, Solomon, and Burne-Jones work. Androgyny confused the boundaries, creating the mystery, sensuality, and desire that motivated and inspired the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to create works that paved the way for future aestheticism. 42 Bram Dijkstra, "The Androgyne in Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature," 73. 12 Bibliography Bullen, J. B. The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire In Painting, Poetry, and Criticism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998. Casteras, Susan P. "Pre-Raphaelite Challenges to Victorian Canons of Beauty." Huntington Library Quarterly 55, no. 1 (1992): 13-35. Cheney, Liana. Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings: The Pygmalion of the Pre-Raphaelite Painters. New York: Peter Lang, 2014. Cruise, Colin. “‘Lovely devils’: Simeon Solomon and Pre-Raphaelite masculinity.” In Re-Framing the Pre-Raphaelites: Historical and Theoretical Essays. Edited by Ellen Harding. Aldershot, England: Scolar Press, 1996. Danahay, Martin A. "Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Virtual Bodies." Victorian Poetry 36, no. 4 (1998): 379-98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40002232. Dijkstra, Bram. "The Androgyne in Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature." Comparative Literature 26, no. 1 (1974): 62-73. Kestner, Joseph. "Edward Burne-Jones and Nineteenth-Century Fear of Women." Biography 7, no. 2 (1984): 95-122. http://www.jstor.org.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/stable/23539153. Ovid, and Rolfe Humphries. Metamorphoses. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983. Plato., and Avi Sharon. Plato's Symposium. Newburyport, MA: Focus Pub./R. Pullins Co., 1998. Riede, David G. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Limits of Victorian Vision. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983. Warner, Malcolm, “The Pre-Raphaelites and the National Gallery.” In Pre-Raphaelite Art In Its European Context, Madison, Susan P. Casteras, and Alicia Craig Faxon[N.J.]: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994. Wilson, Leulla M. "Simeon Solomon—A Dreamer of Dreams." Fine Arts Journal 25, no. 3 (1911): 162-66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23906225. 13 Figure 1: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ecce Ancilla Domini, or The Annunciation, 1850. 14 Figure 2: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Bocca baciata, 1859. 15 Figure 3: Simeon Solomon, Bacchus, 1867. 16 Figure 4: Edward Burne-Jones, Phyllis and Demophoon, 1870, Tree of Forgiveness, 1881-82 17 Figure 5: Edward Burne-Jones, The Rock of Doom and The Doom Fulfilled, oil on canvas, 1888 Figure 6: Earlier version: Perseus and Andromeda, oil on canvas, 1876 18 Figure 7: Edward Burne-Jones, Pygmalion (first series): The Heart Desires, 1868–70, The Hand Refrains, 1868–1870, The Godhead Fires, 1868–70, The Soul Attains, 1868–70 a. b. c. d. Outline: 19 I. II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. VIII. IX. X. Introduction A. The Pygmalion Myth B. Pre-Raphaelite Body C. Thesis: Within the Pre-Raphaelite circle, a visual connection can be made in regards to their pursuit of the ideal image and innovation towards the mixing of gendered attributes to create their ideal. The History of Androgynous Ideals The Origin of the PRB Dante Gabriel Rossetti A. His spiritualism B. Fear and desire and perfection through spiritual means Pygmalion and the quest for purity A. Desire turned to flesh B. Birth of “fleshly school of painting” C. Bocca baciata 1. Transition to Simeon Solomon Simeon Solomon A. Prodigy focused on male figure B. Bacchus Edward Burne-Jones A. Background in the PRB B. His obsession with renaissance art, michelangelo, ovid The gendered binary in many of his works using both female and male figures A. Phyllis and Demophoon (1870) B. The Baleful Head (Fig. 4, 1887), The Rock of Doom and The Doom Fulfilled (Fig. 5,1888) 1. Perseus and Andromeda (1876) 2. The ideal starts as an unachievable desire but then becomes flesh a) Perseus does not realize Andromeda is flesh until he see the tears falling from her eyes- Ovid Pygmalion series A. Burne-Jones search for the aesthetic ideal B. Love of beauty- love of self C. The power of creativity to create a synthesis of the human figure Concluding remarks and research questions still to be answered A. Summary of research and findings B. Further questions and research 20