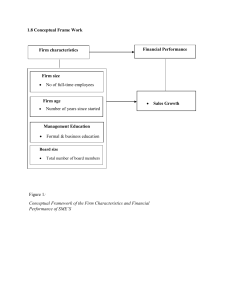

The University of British Columbia Department of Civil Engineering Civil 201: Project Description Objective This semester, you will develop a conceptual design of a tiny home. Each assignment over the semester will contribute to a final assignment. Your team will: i) develop and write a project vision, ii) present a draft conceptual design and plan, and then iii) write a project budget and plan. All of these will contribute to your final conceptual design proposal. Through these assignments, you will practice including community, economic, environmental, and technical constraints and goals. You’ll strategically plan and negotiate the technical and community partnerships that will create an economically and technically successful project. Your team will do this by selecting a group of stakeholders and project collaborators inspired by real tiny home projects. Context Tiny homes offer a scalable solution for the rising demand for affordable housing. The tiny home movement advocates for a sustainable way of living; where people downsize their living space and simplify their way of life. A typical house in North America ~2600 sqft, the average tiny home ranges from 100 - 400 sqft [1]. As a result of COVID-19 “work from home” has been normalized, giving many people the flexibility to work from anywhere. The project will involve the conceptual design of an innovative tiny home. The site location and client(s) will impact the geotechnical design, climate resilience, engineering standards and project collaborators involved. Moreover, your team will get the opportunity to explore ways in which Indigenous, local, and traditional construction knowledge can inform your design process in economically feasible ways. The conceptual design will include material selection, structural, geotechnical, and water resource system designs to meet tiny home water demands, the cost estimate of the tiny home’s detailed design and construction, and a cutting edge design component that fosters a positive impact on society, culture, mental and/or physical health. Additionally, your conceptual design must account for accessibility requirement(s) informed by your community consultation plan. Lastly, the conceptual design must address at least one of the LEED certification standards within the two highlighted categories shown in figure 1 [2]. Figure 1. LEED certification categories [2] The tiny home should be approximately 400 square feet and must adhere to client specifications and the Vancouver codes and standards for engineering design. Your project will be regulated by the National Building Code of Canada, Canadian Standards association (CSA), BC building code and Vancouver building By-Law [3]. Figure 2. Shows a living example of a sustainable tiny home with a green roof built in Ecuador. This design chose to explore traditional construction methods to meet new sustainable building standards in Ecuador. Figure 2. A tiny home in Ecuador built using traditional construction techniques designed by Luis Velasco Roldan and Angel Hevia Antuña [4] Collaborators for Three Different Design Options: Your group will select one of the three tiny house conceptual design projects listed below. 1. OPTION 1: Emergency transitional housing for Ukrainian refugees Better Shelter is a Swedish foundation that provides temporary shelter and refugee housing units (RHU) for displaced families. They aim to promote improved health and education through their built infrastructure. UNHCR collaborated with Better Shelter to provide sustainable refugee housing units in 2013 in Lebanon and Iraq. After the success from this partnership they have continued to collaborate on issues concerning sustainable housing for refugees. The war in Ukraine has displaced more than fourteen million people from their homes. Better Shelter is working on providing temporary shelters for the growing displaced population in Ukraine and its neighboring countries [5]. Your project team has been hired to consult as junior civil engineers to help inform the design process to build 10 sustainable tiny homes in Dubliany a. Project Collaborators: i. UNHCR ii. Better shelter iii. Displaced families from Ukraine War iv. Local material/construction supplier Figure 3. Plan to Develop a Temporary Housing Village For Refugees in Lviv [6] Figure 4. Site location for stakeholder option 1: 49.901423, 24.074603 [7] Guiding questions for Aspirational Design: ● How does tiny home arrangement impact mental health and wellbeing within the community? ● How can green infrastructure support and promote public health goals? ● How does material selection affect outdoor surface temperature? Indoor temperature and air quality for your clients? 2. OPTION 2: Temporary housing in the downtown eastside of Vancouver, Canada The City of Vancouver has approved a two year Tiny Shelter Project to provide temporary emergency housing for people who might otherwise be experiencing homelessness. There is a large amount of community interest in developing an actionable solution through the implementation of tiny homes. Project collaborators who have expressed interest include churches, academic institutions and construction service providers. Moreover, this project aims to collaborate with the Lu’uma Native housing society to create space for decolonization and reconciliation. They have hired a team of junior civil engineers to develop a conceptual design for 10 tiny shelter structures at 875 Terminal Avenue, the parking lot at the Klahowya Tilicum Lalum shelter [3]. Builders without borders is currently working on a project with UBC Sustaingineering, FPInnovations and the Heiltsuk nation and builders without borders would also like to collaborate with your team to build tiny homes [8]. a. Project Collaborators: i. Lu’uma Native Housing Society ii. Homeless community around the Downtown Eastside iii. The City of Vancouver iv. UBC Sustaingineering v. Builders Without Borders Figure 5. Site location for stakeholder option 2: Parking lot at 875 Terminal Avenue [3] Guiding question for Aspirational Design: ● What role has Cory Douglas’ work played in reconciliation and design? ● How does building design and access to natural light impact our circadian rhythm? ● In direct response to the problems caused by social isolation, how can tiny home arrangement promote community interaction? 3. OPTION 3: Laneway home conceptual design for Point Grey, Vancouver, Canada The City of Vancouver is requesting proposals to develop a conceptual design for a standardized laneway home. Section 11 from the zoning and development bylaw currently states that a laneway house is “defined as a detached one-family dwelling constructed in the rear yard of a site with a one-family dwelling or one family dwelling with secondary suite. A laneway house may not exceed the lesser of 0.16 FSR (with the building area dependent on the site size) or 86.3 sq. m (929 sq. ft.)” [9]. Laneway homes provide a scalable and more permanent solution to address affordable housing concerns. The design of a standard laneway home can save the cost of individual laneway home design, make the process easier and the price more predictable, and select required materials and resources available under current supply chain constraints. Campos Studio is interested in collaborating with your team to develop a conceptual design for a standard laneway home in Point Grey. a. Project Collaborators: i. The City of Vancouver ii. UBC students iii. UBC design teams iv. Campos Studio Figure 6. Sample laneway home project on 4022 Quesnel Drive [10] Figure 7. Miko Laneway Housing Project from Campos Studio in Point Grey [11] Since your laneway home design won’t be site specific you will work with a geotechnical engineer to account for different subsurface conditions that will affect your building material selection. You may situate your conceptual design on 4022 Quesnel drive as it provides the appropriate design conditions for a laneway housing project in Point Grey. Figure 8. Infographic for a one-family laneway home [12] Guiding questions for Aspirational Design: ● How will your laneway home location account for the existing built environment to maximize the ease of walking and biking? ● How does access to green space affect mental and physical health? ● How will your lineway home account for bike and stroller storage? Design Criteria Your conceptual design must be technically feasible and meet the minimum requirements for capital cost, accessibility, and comply with the National Building Code of Canada, Canadian Standards association (CSA), BC building code and Vancouver building By-Law [3]. Criterion Description Weight (%) Cost Total cost of ownership including the initial capital cost 30 Resilience Ability to withstand regionally appropriate shocks (earthquake, tornado, hot/cold weather events) 30 User Experience Livability (convenience and comfort undertaking daily tasks*), airflow and air quality, indoor temperature, provides appropriate accommodation for accessibility requirements informed by community consultation. 20 Environmental Sustainability Addresses core LEED sustainability standards for building and design 15 Social Impact Addresses a social inequality (eliminates poverty), creates physical space for community events/gardens, 5 *you will need to define what daily tasks this structure supports Scope of Work The conceptual design is expected to give attention to the following elements: ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● A search for and review of available information relating to the project objective, including three precedent examples of tiny homes. A review of existing aspirational design elements that foster a positive impact on society, culture, mental and/or physical health. A review of issues, criteria, and assumptions, A formal decision-making process in the selection of preferred technical design elements. A review of appropriate building codes and standards A description of your chosen client, and how they inform the design process A task list with project collaborators in and out of civil engineering. An evaluation of three realistic and distinct design options reflecting materials, structural and geotechnical elements, locations, access, safety, and climate resilience. A selection of LEED system goals on building design. A review of collaborative design thinking and human centered design. A presentation and written conceptual design proposal, in accordance with specified requirements. A cost estimate of the proposed option. Transportation engineering is out of scope for this design project. Power and electricity calculations are out of scope for this design project. APPENDIX A – PROJECT RESOURCES [1] “What is the tiny house movement? why tiny houses?,” The Tiny Life, 02-Mar-2022. [Online]. Available: https://thetinylife.com/what-is-the-tiny-house-movement/ . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [2] “LEED scorecard,” LEED scorecard | U.S. Green Building Council. [Online]. Available: https://www.usgbc.org/leed-tools/scorecard . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [3] “Report contact no.: 604-673-8287 submit comments to council ... - vancouver.” [Online]. Available: https://council.vancouver.ca/20220209/documents/cfsc3.pdf . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [4] “Tiny Green-roofed house proves the superiority of Ecuador's traditional construction techniques,” Inhabitat, 16-Oct-2015. [Online]. Available: https://inhabitat.com/green-roofed-lightweight-house-proves-the-superiority-of-ecuadors-traditional-c onstruction-techniques/ . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [5] The Plaid Zebra and [Email Protected], “IKEA designs pre-made tiny-homes to send to refugee camps around the world,” The Plaid Zebra, 24-Feb-2021. [Online]. Available: https://theplaidzebra.com/ikea-designs-pre-made-tiny-homes/ . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [6] “The temporary housing for migrants to be constructed in two communities of the Lviv Region,” Твоє Місто - твоє телебачення. [Online]. Available: https://tvoemisto.tv/en/news/the_temporary_housing_for_migrants_to_be_constructed_in_two_comm unities_of_the_lviv_region_130212.html . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [7] Google maps. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/maps/place/49%C2%B054'05.1%22N+24%C2%B004'28.6%22E/@49.9014 229,24.0701237,612m/data=!3m2!1e3!4b1!4m6!3m5!1s0x0:0x88a8e8b59cd7b074!7e2!8m2!3d49.90 14229!4d24.074603 . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [8] “Tiny Homes Project,” Indigenous Research Support Initiative. [Online]. Available: https://irsi.ubc.ca/tiny-homes-project . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [9]“Additional regulations for specific uses - vancouver.” [Online]. Available: https://bylaws.vancouver.ca/zoning/zoning-by-law-section-11.pdf . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [10] Google maps. [Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/maps/place/4022+Quesnel+Dr,+Vancouver,+BC+V6L+2X2/@49.2509201,123.1726786,196m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x5486730947e1966f:0x1740bcb9f46cd5cc!8m2!3d 49.2508495!4d-123.1724388 . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [11] “Point grey laneway,” Campos Studio. [Online]. Available: https://www.campos.studio/point-grey-laneway/ . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [12] “Housing options in most RS zones brochure - vancouver.” [Online]. Available: https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/housing-options-in-most-rs-zones-brochure.pdf . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. APPENDIX B – Additional Supporting resources [1] W. Wu and B. Hyatt, “Experiential and project-based learning in BIM for sustainable living with tiny solar houses,” Procedia Engineering, vol. 145, pp. 579–586, 2016. [2] “First in the World Tiny House awarded prestigious LEED Platinum Green Building Certification,” U.S. Green Building Council. [Online]. Available: https://www.usgbc.org/articles/first-world-tiny-house-awarded-prestigious-leed-platinum-green-buildingcertification . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [3] S. McNulty-Kowal, “This rammed earth tiny home concept reinterprets farmhouses with a pitched green roof and photovoltaic panels! - yanko design,” Yanko Design - Modern Industrial Design News, 27-Aug-2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.yankodesign.com/2021/08/27/this-rammed-earth-tiny-home-concept-reinterprets-farmhouses -with-a-pitched-green-roof-and-photovoltaic-panels/ . [Accessed: 24-Aug-2022]. [4] L. Heidari, M. Younger, G. Chandler, J. Gooch, and P. Schramm, “Integrating health into buildings of the future,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 139, no. 1, 2016.