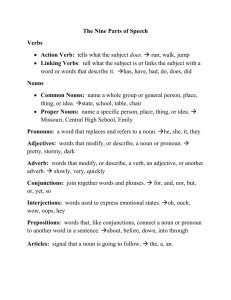

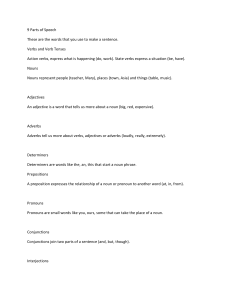

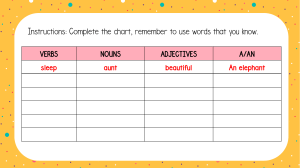

GRAMMAR GUIDE GRAMMATIK FÜHRER A) KINDS OF WORDS (WORTARTEN) NOUNS (NOMEN) can be people, places, objects, animals, plants, feelings, behaviours, ideas, attitudes... The latter four are “abstract” nouns, i.e. they cannot easily be imagined in one simple image. The opposite of “abstract” is “concrete”, which is to say things that can be seen, felt, easily visualized, touched. With the exception of proper names, which are also nouns, a test whether something is a noun or not is whether you can say “the” before the word, and it makes sense. EXAMPLES: (the) man, (the) city, (the) board, (the) leopard, (the) hedge, (the) love, (the) courtesy, (the) politics, (the) racism. GERMAN NOUNS always have a capital letter. They can be masculine (the = der), feminine (the = die), or neuter (the = das). The nouns above are, in German: (der) Mann, (die) Stadt, (das) Brett, (der) Leopard, (die) Hecke, (die) Liebe, (die) Höflichkeit, (die) Politik, (der) Rassismus. VERBS (VERBEN) are words that denote an action. Be aware that not every action is a visible action, or one that involves movement. A good example for this is “to think”, or “to analyze”, they happen in our heads. They can also be “impersonal”, that is people can’t do them, but they’re still an action, for example “to rain”. If you want to test whether a word is a verb, try and say “to” in front of it, and see if it makes sense, OR ask yourself “Can one xxx?” Verbs change a lot, they can be in different times (rain, rained), person (I think, he thinks). I will discuss this under C) FORMS. EXAMPLES: (to) kick, (to) like, (to) breathe, (to) collect, (to) be, (to) confirm, (to) investigate GERMAN VERBS have even more forms (ich wohne, du wohnst, er wohnt…). The verbs above are: (zu) treten/kicken, (zu) mögen), (zu) atmen, (zu) sammeln, (zu) sein, (zu) bestätigen, (zu) investigieren/untersuchen. They end, in their basic form (the infinitive), almost always in –en ADJECTIVES (ADJEKTIVE) are words that further describe a noun. You can either put them in front of a noun to go into more detail what sort of a noun it is; EXAMPLES: a nasty man, a large city, a wooden board, a fierce leopard, a tidy hedge, an incurable love, a false courtesy, disastrous politics, vile racism) OR they can complement a form of to be (I am, you are, he is, we are, you are, they are…hungry/cute/annoying/useless…). To check if a word is an adjective, see if it answers the question “what sort of a (noun) is the noun?”, e.g. what sort of a man is he? A NASTY man. The only way adjectives change in English is in comparisons. Short adjectives have three forms, for example: nasty, nastier, nastiest. In German, they can also have endings, depending on where they are in a sentence and whether the noun it refers to is a masculine, feminine or neuter one. The adjectives above are: gemein, groß, hölzern, wild, sauber, unheilbar, falsch, desaströs, abscheulich) ADVERBS (ADVERBIEN) are words that further tell you, in one word only, how, when or where a verb is done, If adjectives further describe nouns, then adverbs further describe verbs. There are two kinds of adverbs. The easily visible variety in English end in –ly (nastily, largely, fiercly, tidily…). In German, those look no different from adjectives and have NO ending, in almost all cases. The other variety is adverbs of place and time, mainly, such as: there, outside, upstairs, yesterday, then or later. By the way, English is a very flexible language, and you can MAKE nouns out of other words (“the table is upstairs”: upstairs is an adverb, but “the upstairs is very nice”, it’s now a noun), or even verbs out of other words. (“the text was short”, text is a noun, but “let’s text each other”, now it’s a verb!) The former four kinds of words could be called the big ones, and there are a great number of them. They are often long, and they are what gives the most important information in a sentence. If you JUST had those kinds of words, you couldn’t say very clever sentences, but you could make yourself understood: “Nasty man smells bad, has nice eyes. Friends went cinema, movie was funny.” What is missing in these sentences are small words, you could call them function words. If the big ones are the flesh of a sentence, the little words are the skeleton. They hold sentences together, and connect them, give them a relationship. For example, the sentences above sound better like this: THE nasty man smells QUITE bad, BUT HE has nice eyes. MY friends went TO THE cinema, THE movie was funny. There are not so many of these words in each category, but they are very very frequent. The most frequent words in English are for example “and” and “I”. PRONOUNS (PRONOMEN) are maybe actually somewhere between big words and function words. They REPLACE a noun when you don’t want to keep repeating it (pro-noun), and have the same function, generally. The pronouns in English are: I (me), you, he (him)/she(her)/it, we (us), you, they (them). German has more forms, but the basic ones are Ich, du, er/sie/es, wir, ihr, sie. CONJUNCTIONS (KONJUNKTIONEN) are words that link words or sentences. Obvious ones, in English, are “and”, “or”, “but”, less obvious ones are “because”, “although”, “when” (When I was a child…), “that” (I have read that he won the race). ARTICLES (ARTIKEL) are little words in front of nouns, they don’t stand alone: Definite Article: The (der, die, das, and other forms, such as den, dem) dog Indefinite Article: A (ein, eine, ein, einen, einem) dog Possessive Article: My (mein, meine…) dog Your (dein, deine…) dog His (sein, seine…) dog Her (ihr, ihre…) dog Etc Demonstrative Article: This/That (dieser, diese, dieses) dog Negative Article: No (kein, keine, kein…) dog + a few more such as each (jeder/jede/jedes) or some (mancher/manche/manches) PREPOSITIONS (PRÄPOSITIONEN) are words that put a phrase (group of words) in relation to the sentence as to when, where or how something happened. EXAMPLE: How? WITH a hammer (German: MIT) Where? ON the table (German: AUF) When? 100 years AGO (German: VOR 100 Jahren) Other examples are against (gegen), for (für), in (in), to (zu), next to (neben), between (zwischen), from (von), since (seit), after (nach). The list isn’t very long, however prepositions are not always the same in different languages, for example in English you are “on the bus”, in German “in the bus”. They are important, and a little difficult to get right! THERE ARE SOME OTHER SMALL CATEGORIES OF KINDS OF WORDS, but I have covered the ones that cause difficulties and ought to be learnt and understood. Question words (Fragewörter), or “Interrogatives” (when, where, who etc) are relatively easy and straight forward. The other ones are not as important. B) WORD FUCTIONS (SATZFUNKTIONEN) Having talked about single words, and how you can categorize them, I am now going to talk about what a word, or a group of words that belongs together, DOES within a sentence. This is sometimes referred to as ONE IDEA, or ONE UNIT. For example, when we ask the question “who carries out the verb in this sentence?”, you could have a very short answer, or a long “phrase”. Whatever answers this “who?” question is THE SUBJECT (DAS SUBJEKT) EXAMPLE: Klaus lives in Munich. WHO lives in Munich? KLAUS is the subject. (Klaus wohnt in München. WER wohnt in München?) Here the subject consists of only one word, namely the name Klaus. See another example: My good friend Klaus lives in Munich. WHO lives in Munich? (Mein guter Freund Klaus wohnt in München) The subject (answer to “who?”) here consists of 4 words: My good friend Klaus. My is an article, good is an adjective, friend is a noun, Klaus is another noun. They are ONE IDEA, or ONE UNIT, you cannot split them into a smaller unit, logically, they express only one function, namely WHO lives in Munich. Any noun can be a subject, so sometimes it’s a matter of WHAT, rather than WHO. (Love conquers everything). German plays around with word order more than English, so becareful not to assume the first unit in a sentence is the subject: In München wohnt mein guter Freund Klaus. THE PREDICATE (DAS PRÄDIKAT) is a word to summarize all the verbs in one sentence. Many sentences have only one verb, and therefore the verb IS the predicate, like in “Klaus lives in Munich”, the predicate is “lives”. But look at this example: I have been trying to learn Chinese for years. You have three verbs here: have, been (from to be) and trying (from to try). Together, they are the predicate. Another verb phrase, that’s a separate unit, depends on it (to learn). OBJECTS (OBJEKTE) are complements to verbs, and have a noun or pronoun at their heart, but they are not the subject. You ask, in correct/old-fashioned English: Whom or what does the subject like/buy/read/eat/analyze? EXAMPLE: I give my grandfather a nice CD. (Ich gebe meinem Opa eine schöne CD.) WHO does the verb? – I: subject WHAT do I give? – a nice CD: object (here a “direct object”) TO WHOM do I give the book? – to my grandfather: object (here “indirect”) The distinction of direct object and indirect object is maybe not obvious, it will be taught. What is important for now is that they are phrases following on from the verb, but have no prepositions: giving WHAT? Giving it to WHOM (in German never with a “to” word)? Verbs affect objects. PREPOSITIONAL PHRASES/ADVERBIAL PHRASES (Präpositionalphrasen/Adverbialphrasen) … are similar to adverbs, as they also answer the questions “how, when and where”, but rather than in a single word (nastily, yesterday, upstairs), they do it in a phrase introduced by a preposition: HOW did he die? FROM a stroke (preposition, article and noun) WHEN shall we meet? AT six in the evening (preposition, numeral, preposition, article, noun) WHERE is my jumper? IN the basket (preposition, article, noun) C) FORMS (FORMEN) If you put a word in a certain place in a sentence, and it has to fulfill a function, it can change its look, for example by taking an ending, or sometimes by changing its spelling in the middle. This is called forms. Various aspects affect various kinds of words. Some words never change, such as conjunctions. Examples for changes are: PLURAL affects NOUNS (sofa - sofas, woman - women). PERSON affects VERBS (I read – he reads, wir wohnen – ihr wohnt). PAST affects VERBS (I am – I was, ich habe – ich hatte (had)). They’re the same word in different forms. NOUNS are affected by: Singular or plural? (woman, women) Sometimes gender (actor, actress), but in German more frequently In German only: function as subject or object, or after prepositions (this is called CASE), English does it to pronouns: he (subject) is nice, I like him (object). EXAMPLE: Meine Freunde (my friends), but mit meinen Freunden (with my friends); both the article and the noun have assumed a different form. VERBS are the most affected words, in English we have forms for present and past (tense), 3rd person –s (conjugation, someone else does the verb now!), as well as present or past “participles”: go, went, goes, going (present participle), gone (past participle) are all forms of to go. All of these, and some more, affect German verbs too. This is a complex part of the grammar guide and needs to be explained slowly and bit by bit. ADJECTIVES in English don’t change except when used in comparisons (big, bigger, biggest), German does this too, but also changes their endings according to the “case” of the noun in a sentence that it precedes: EXAMPLE: Die große Frau wohnt in Köln. (The tall woman lives in Cologne) BUT Er gibt der großen Frau Hilfe. (He gives the tall woman help). In the above example you can also see that ARTICLES change in the same circumstances (die changed to der!); they also change with gender and number. ADVERBS that are derived from an adjective take the suffix (ending syllable) –ly in English, but in German, an ending to show an adjective has become an adverb is rare (normal => normalerweise is the most famous exception). PROUNOUNS change in same way as nouns, and this is true for English and German. For example: He is very funny. I like HIM. (“he” has changed to “him” because it is the object of the verb “to like”) Er ist sehr lustig. Ich mag IHN. The other little words do not change. DO NOT CONFUSE KINDS OF WORDS, FUNCTIONS, AND FORMS! Different ways of speaking about words and sentences!