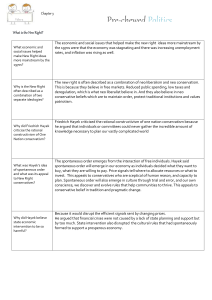

F.A. Hayek: Economics, Political Economy, Social Philosophy

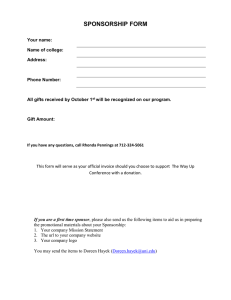

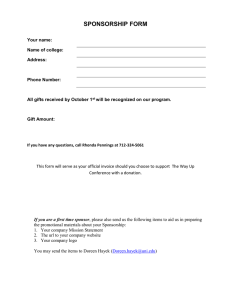

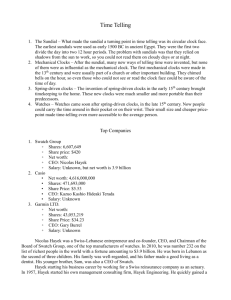

advertisement