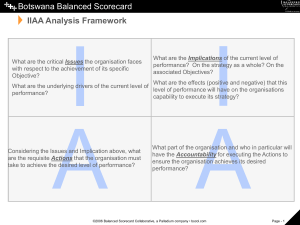

gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 438 12/25/06 3:32:32 PM epg1 /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES Chapter 10 438 3. 4. 5. 6. example, workers may put on a crash effort to increase output at the end of the month to avoid an unfavorable labor efficiency variance. In the rush to produce more output, quality may suffer. Labor quantity standards and efficiency variances make two important assumptions. First, they assume that the production process is labor-paced; if labor works faster, output will go up. However, output in many companies is not determined by how fast labor works; rather, it is determined by the processing speed of machines. Second, the computations assume that labor is a variable cost. However, direct labor may be essentially fixed. If labor is fixed, then an undue emphasis on labor efficiency variances creates pressure to build excess inventories. In some cases, a “favorable” variance can be as bad or worse than an “unfavorable” variance. For example, McDonald’s has a standard for the amount of hamburger meat that should be in a Big Mac. A “favorable” variance would mean that less meat was used than the standard specifies. The result is a substandard Big Mac and possibly a dissatisfied customer. Too much emphasis on meeting the standards may overshadow other important objectives such as maintaining and improving quality, on-time delivery, and customer satisfaction. This tendency can be reduced by using supplemental performance measures that focus on these other objectives. Just meeting standards may not be sufficient; continual improvement may be necessary to survive in a competitive environment. For this reason, some companies focus on the trends in the standard cost variances—aiming for continual improvement rather than just meeting the standards. In other companies, engineered standards are replaced either by a rolling average of actual costs, which is expected to decline, or by very challenging target costs. In sum, managers should exercise considerable care when using a standard cost system. It is particularly important that managers go out of their way to focus on the positive, rather than just on the negative, and to be aware of possible unintended consequences. Nevertheless, standard costs are found in the vast majority of manufacturing companies and in many service companies, although their use is changing. For evaluating performance, standard cost variances are often complemented by a performance measurement system called the balanced scorecard, which is discussed in the next section. The balanced scorecard concept has been eagerly embraced by a wide variety of organizations including Analog Devices, KPMG, Tenneco, Allstate, AT&T, Elf Atochem, Conair-Franklin, CIGNA Corporation, London Life Insurance Co., Southern Gardens Citrus Processing, Duke Children’s Hospital, JP Morgan Chase, 3COM, Rockwater, Apple Computer, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), FMC, the Bank of Montreal, the Massachusetts Special Olympics, United Way of Southeastern New England, Boston Lyric Opera, Bridgeport Hospital and Healthcare Services, Housing Authority of Fiji, and Verizon Communications. It has been estimated that about half of all Fortune 1000 companies have implemented a balanced scorecard. Balanced Scorecard LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5 Understand how a balanced scorecard fits together and how it supports a company’s strategy. A balanced scorecard consists of an integrated set of performance measures that are derived from and support the company’s strategy throughout the organization. A strategy is essentially a theory about how to achieve the organization’s goals. For example, Southwest Airlines’ strategy is to offer an operational excellence customer value proposition that has three key components—low ticket prices, convenience, and reliability. The company operates only one type of aircraft, the Boeing 737, to reduce maintenance and training costs and simplify scheduling. It further reduces costs by not offering meals, seat assignments, or baggage transfers and by booking a large portion of its passenger revenue over the Internet. Southwest also uses point-to-point flights rather than the hub-and-spoke approach of its /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 439 12/25/06 3:32:33 PM epg1 Standard Costs and the Balanced Scorecard 439 larger competitors, thereby providing customers convenient, nonstop service to their final destination. Since Southwest serves many less-congested airports such as Chicago Midway, Burbank, Manchester, Oakland, and Providence, it offers quicker passenger check-ins and reliable departures, while maintaining high asset utilization (i.e., the company’s average gate turnaround time of 25 minutes enables it to function with fewer planes and gates). Overall, the company’s strategy has worked. At a time when Southwest Airlines’ larger competitors are struggling, it continues to earn substantial profits. Under the balanced scorecard approach, top management translates its strategy into performance measures that employees can understand and influence. For example, the amount of time passengers have to wait in line to have their baggage checked might be a performance measure for the supervisor in charge of the Southwest Airlines check-in counter at the Burbank airport. This performance measure is easily understood by the supervisor, and can be improved by the supervisor’s actions. IN BUSINESS WHY DO COMPANIES FAIL TO EXECUTE THEIR STRATEGIES? Robert Paladino served as the vice president and global leader of the Telecommunications and Utility Practice for the Balanced Scorecard Collaborative—a consulting organization that works with companies to implement balanced scorecards. He offers four reasons why nine out of ten organizations fail to execute their business strategies. First, only 5% of a company’s workforce understands their organization’s strategy. Paladino commented “if employees don’t understand the strategic objectives, then they could be focused on closing the wrong performance gaps.” Second, 85% of management teams spend less than one hour per month discussing strategy. Managers cannot effectively implement strategies if they do not spend enough time talking about them. Third, 60% of organizations do not link their budgets to strategy. The inevitable result is that companies pursue “financial strategies that differ from or, worse, may be in conflict with their business and customer quality strategies.” Finally, only 25% of managers have their incentives linked to strategy. Thus, most managers are working to maximize their compensation by improving strategically misguided metrics. Paladino says the balanced scorecard overcomes these four barriers because it helps employees focus their actions on executing organizational strategies. Source: Robert E. Paladino, “Balanced Forecasts Drive Value,” Strategic Finance, January 2005, pp. 37–42. Common Characteristics of Balanced Scorecards Performance measures used in the balanced scorecard approach tend to fall into the four groups illustrated in Exhibit 10–10 (page 440): financial, customer, internal business processes, and learning and growth. Internal business processes are what the company does in an attempt to satisfy customers. For example, in a manufacturing company, assembling a product is an internal business process. In an airline, handling baggage is an internal business process. The idea underlying these groupings (as indicated by the vertical arrows in Exhibit 10–10) is that learning is necessary to improve internal business processes; improving business processes is necessary to improve customer satisfaction; and improving customer satisfaction is necessary to improve financial results. Note that the emphasis in Exhibit 10–10 is on improvement—not on just attaining some specific objective such as profits of $10 million. In the balanced scorecard approach, continual improvement is encouraged. If an organization does not continually improve, it will eventually lose out to competitors that do. Financial performance measures appear at the top of Exhibit 10–10. Ultimately, most companies exist to provide financial rewards to owners. There are exceptions. Some companies—for example, The Body Shop—may have loftier goals such as providing environmentally friendly /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 440 12/25/06 3:32:35 PM epg1 440 E X H I B I T 10–10 From Strategy to Performance Measures: The Balanced Scorecard Chapter 10 Performance Measures Financial "Has our financial performance improved?" What are our financial goals? Customer "Do customers recognize that we are delivering more value?" What customers do we want to serve and how are we going to win and retain them? Internal Business Processes "Have we improved key business processes so that we can deliver more value to customers?" What internal business processes are critical to providing value to customers? Vision and Strategy Learning and Growth "Are we maintaining our ability to change and improve?" products to consumers. However, even nonprofit organizations must generate enough financial resources to stay in operation. However, for several reasons, financial performance measures are not sufficient in themselves—they should be integrated with nonfinancial measures in a well-designed balanced scorecard. First, financial measures are lag indicators that report on the results of past actions. In contrast, nonfinancial measures of key success drivers such as customer satisfaction are leading indicators of future financial performance. Second, top managers are ordinarily responsible for the financial performance measures—not lowerlevel managers. The supervisor in charge of checking in passengers can be held responsible for how long passengers have to wait in line. However, this supervisor cannot reasonably be held responsible for the entire company’s profit. That is the responsibility of the airline’s top managers. We will have more to say about financial performance measures in later chapters. Exhibit 10–11 lists some examples of performance measures that can be found on the balanced scorecards of companies. However, few companies, if any, would use all of these performance measures, and almost all companies would add other performance measures. Managers should carefully select performance measures for their own company’s balanced scorecard, keeping the following points in mind. First and foremost, the performance measures should be consistent with, and follow from, the company’s strategy. If the performance measures are not consistent with the company’s strategy, people will find themselves working at cross-purposes. Second, the performance measures should be understandable and controllable to a significant extent by those being evaluated. Third, the scorecard should not have too many performance measures. This can lead to a lack of focus and confusion. While the entire organization will have an overall balanced scorecard, each responsible individual will have his or her own personal scorecard as well. This scorecard should /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 441 12/25/06 3:32:36 PM epg1 Standard Costs and the Balanced Scorecard Customer Perspective Performance Measure Desired Change Customer satisfaction as measured by survey results Number of customer complaints Market share Product returns as a percentage of sales Percentage of customers retained from last period Number of new customers Internal Business Processes Perspective Desired Change Performance Measure Percentage of sales from new products Time to introduce new products to market Percentage of customer calls answered within 20 seconds On-time deliveries as a percentage of all deliveries Work in process inventory as a percentage of sales Unfavorable standard cost variances Defect-free units as a percentage of completed units Delivery cycle time* Throughput time* Manufacturing cycle efficiency* Quality costs† Setup time Time from call by customer to repair of product Percent of customer complaints settled on first contact Time to settle a customer claim Learning and Growth Perspective Performance Measure Desired Change Suggestions per employee Value-added per employee‡ Employee turnover Hours of in-house training per employee *Explained later in this chapter. † See Appendix 2B, Cost of Quality. ‡ Value-added is revenue less externally purchased materials, supplies, and services. consist of items the individual can personally influence that relate directly to the performance measures on the overall balanced scorecard. The performance measures on this personal scorecard should not be overly influenced by actions taken by others in the company or by events that are outside of the individual’s control. And, focusing on the performance measure should not lead an individual to take actions that are counter to the organization’s objectives. With those broad principles in mind, we will now take a look at how a company’s strategy affects its balanced scorecard. 441 E X H I B I T 10–11 Examples of Performance Measures for Balanced Scorecards gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 442 12/25/06 3:32:37 PM epg1 442 /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES Chapter 10 IN BUSINESS LOSING SIGHT OF THE CUSTOMER Understanding customer needs sounds simple enough, but it is surprising how often companies lose sight of what their customers want. For example, Waste Management, one of the largest trash haulers in the United States, assumed that its customers were most interested in receiving low prices. However, when the company actually surveyed its customers, it found out that they were more concerned about billing errors and missed garbage pickups. Waste Management responded to this feedback by upgrading its billing program—as a result customers are paying their bills in an average of 47 days instead of 71. Not only are customers happier with fewer billing errors, but shaving 24 days off the accounts receivable collection cycle is worth $30 million per day to the company! Waste Management also addressed the issue of missed garbage pickups by initiating a program called Haul or Call. When a garbage truck driver sees an impediment blocking a garbage bin, his home office calls the customer to see when they can reschedule a pickup. Customers have been so impressed with this level of service that their defection rate has dropped from 12% to 8.6% in less than one year. Waste Management has found that the key to improving bottom-line results is gathering information from its customers about the underlying drivers of financial performance. Source: Julie Creswell, “Scandal Hits—Now What?” Fortune, July 7, 2003, pp. 127–130. IN BUSINESS IN DENIAL Larry Bossidy, the long-time CEO of Allied Signal, reports that “When I took over at Allied Signal . . . I got two different pictures from our people and our customers. While our people were saying that we were delivering an order-fill rate of 98%, our customers thought we were at 60%. The irony was, instead of trying to address the customers’ complaints, we seemed to think we had to show that we were right and they were wrong.” Note the two messages contained in this short quotation. First, make sure you measure the right thing. Apparently, the internal measure of order-fill rates that had been used at Allied Signal was deficient—it did not capture customer perceptions, which are of paramount importance. Second, if customers are unhappy, don’t tell them they are wrong. Try to figure out why they are unhappy. Source: Larry Bossidy and Ram Charan, “How Did Honeywell Chairman Larry Bossidy Turn the Company Around? By His Maniacal Focus on Just One Thing: Execution,” Fortune, June 10, 2002, pp. 149–152. A Company’s Strategy and the Balanced Scorecard Returning to the performance measures in Exhibit 10–10, each company must decide which customers to target and what internal business processes are crucial to attracting and retaining those customers. Different companies, having different strategies, will target different customers with different kinds of products and services. Take the automobile industry as an example. BMW stresses engineering and handling; Volvo, safety; Jaguar, luxury detailing; Corvette, racy styling; and Toyota, reliability. Because of these differences in emphases, a one-size-fits-all approach to performance measurement won’t work even within this one industry. Performance measures must be tailored to the specific strategy of each company. Suppose, for example, that Jaguar’s strategy is to offer distinctive, richly finished luxury automobiles to wealthy individuals who prize handcrafted, individualized products. To deliver this customer intimacy value proposition to its wealthy target customers, Jaguar might create such a large number of options for details, such as leather seats, interior and exterior color combinations, and wooden dashboards, that each car becomes /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 443 12/25/06 3:32:38 PM epg1 Standard Costs and the Balanced Scorecard 443 virtually one of a kind. For example, instead of just offering tan or blue leather seats in standard cowhide, the company may offer customers the choice of an almost infinite palette of colors in any of a number of different exotic leathers. For such a system to work effectively, Jaguar would have to be able to deliver a completely customized car within a reasonable amount of time—and without incurring more cost for this customization than the customer is willing to pay. Exhibit 10–12 suggests how Jaguar might reflect this strategy in its balanced scorecard. If the balanced scorecard is correctly constructed, the performance measures should be linked together on a cause-and-effect basis. Each link can then be read as a hypothesis in the form “If we improve this performance measure, then this other performance measure should also improve.” Starting from the bottom of Exhibit 10–12, we can read the links between performance measures as follows. If employees acquire the skills to install new options more effectively, then the company can offer more options and the options can be installed in less time. If more options are available and they are installed in less time, then customer surveys should show greater satisfaction with the range of options available. If customer satisfaction improves, then the number of cars sold should increase. In addition, if customer satisfaction improves, the company should be able to maintain or increase its selling prices, and if the time to install options decreases, the costs of installing the options should decrease. Together, this should result in an increase in the contribution margin Financial Customer Profit + Contribution margin per car + Number of cars sold + E X H I B I T 10–12 A Possible Strategy at Jaguar and the Balanced Scorecard Customer surveys: + Satisfaction with options available Internal Business Processes Learning and Growth Number of options available + Time to install an option Employee skills in installing options + – gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 444 12/25/06 3:32:38 PM epg1 444 /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES Chapter 10 per car. If the contribution margin per car increases and more cars are sold, the result should be an increase in profits. In essence, the balanced scorecard lays out a theory of how the company can take concrete actions to attain its desired outcomes (financial, in this case). While the strategy laid out in Exhibit 10–12 seems plausible, it should be regarded as only a theory. For example, if the company succeeds in increasing the number of options available and in decreasing the time required to install options and yet there is no increase in customer satisfaction, the number of cars sold, the contribution margin per car, or profits, the strategy would have to be reconsidered. One of the advantages of the balanced scorecard is that it continually tests the theories underlying management’s strategy. If a strategy is not working, it should become evident when some of the predicted effects (i.e., more car sales) don’t occur. Without this feedback, the organization may drift on indefinitely with an ineffective strategy based on faulty assumptions. IN BUSINESS CAUSE-AND-EFFECT IS THE KEY Professors Christopher D. Ittner and David F. Larcker surveyed 157 companies and found that only 23% consistently verified the hypothesized cause-and-effect linkages embedded in their balanced scorecards. These companies earned a 5.14% higher return on common stockholders’ equity than the 77% of companies that did not verify their cause-and-effect linkages. The authors found that most companies do not verify cause-and-effect linkages because they erroneously believe that they are self-evident. For example, one fast-food chain chose employee turnover as a performance measure believing that its positive effects on profits were obvious. However, the professors’ research revealed that the fast-food chain’s profitability was only influenced by turnover among its supervisors, not lower-level employees. A broad measure of employee turnover did not help explain differences in profitability across restaurants. Source: Christopher D. Ittner and David F. Larcker, “Coming Up Short on Nonfinancial Performance Measurement,” Harvard Business Review, November 2003, pp. 88–95. Tying Compensation to the Balanced Scorecard Incentive compensation for employees, such as bonuses, can, and probably should, be tied to balanced scorecard performance measures. However, this should be done only after the organization has been successfully managed with the scorecard for some time—perhaps a year or more. Managers must be confident that the performance measures are reliable, sensible, understood by those who are being evaluated, and not easily manipulated. As Robert Kaplan and David Norton, the originators of the balanced scorecard concept point out, “compensation is such a powerful lever that you have to be pretty confident that you have the right measures and have good data for the measures before making the link.”5 Advantages of Timely and Graphic Feedback Whatever performance measures are used, they should be reported on a frequent and timely basis. For example, data about defects should be reported to the responsible managers at least once a day so that action can be quickly taken if an unusual number of defects occurs. In the most advanced companies, any defect is reported immediately, and its cause is tracked down before any more defects occur. Another common characteristic of the performance measures under the balanced scorecard approach is that managers focus on trends in the performance measures over time. The emphasis is on progress and improvement rather than on meeting any specific standard. 5 Lori Calabro, “On Balance: A CFO Interview,” CFO, February 2001, pp. 73–78. /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 445 12/25/06 3:32:39 PM epg1 Standard Costs and the Balanced Scorecard 445 For tracking trends and improvement over time, graphic displays are often far more informative than rows or columns of numbers. Consider, for example, the problem of passengers who reserve seats but do not show up to buy their tickets. Because of these “no-show” passengers, airlines routinely overbook popular flights. The airlines gamble that the number of overbooked passengers will be offset by the number of no-shows. Sometimes airlines lose this gamble. This results in the airline incurring substantial additional costs to either pay passengers to relinquish their reservations or to house and feed excess passengers until suitable replacement flights can be found. Because of these costs (and the ill will created among passengers), airlines carefully monitor the percentage of overbooked seats that actually turn out to be a problem and result in a passenger being bumped from a flight. Suppose, for example, that an airline has recorded the following data over the last 20 weeks: Bumped passengers per hundred overbooked seats Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 7.1 6.5 6.7 7.2 7.0 7.3 6.7 6.5 6.2 5.8 Bumped passengers per hundred overbooked seats Week 11 Week 12 Week 13 Week 14 Week 15 Week 16 Week 17 Week 18 Week 19 Week 20 6.4 6.3 6.7 5.8 6.6 6.6 6.9 7.1 7.4 7.8 10.00 9.0 8.0 7.0 6.0 5.0 4.0 Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 Week 12 Week 13 Week 14 Week 15 Week 16 Week 17 Week 18 Week 19 Week 20 Bumped passengers per 100 overbooked seats These data are plotted in Exhibit 10–13. Note how much easier it is to spot trends and unusual points when the data are plotted than when they are displayed in the form of a table. In particular, the worrisome increase in bumped passengers over the final seven weeks is very evident in the plotted data. E X H I B I T 10–13 The Number of Passengers Bumped per Hundred Overbooked Seats gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 446 12/25/06 3:32:40 PM epg1 446 /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES Chapter 10 IN BUSINESS A PICTURE IS WORTH A THOUSAND NUMBERS Graphics are routinely integrated in Balanced Scorecard reports, with data often displayed on a “dashboard” with representations of gauges and digital readouts. At Beverage Can Americas Co. in Chicago, a division of London-based Rexam Plc., executive dashboards and scorecards are being rolled out to thousands of employees. “Each worker sees a handful of metrics that pertain to his or her job, which are represented as green, yellow, or red icons depending on whether they are satisfactory, borderline, or subpar.” Source: Scott Leibs, “Now You See It,” CFO, July 2002, pp. 61–66. IN BUSINESS CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND THE BALANCED SCORECARD Historically, the board of directors of First Commonwealth Financial Corporation of Pennsylvania had only been given access to financial measures that were required for regulatory purposes. In the aftermath of corporate scandals such as Enron, Tyco, and WorldCom, the board decided to improve its oversight of the corporation by creating a balanced scorecard that not only helped ensure regulatory compliance but that also included forward-looking information about the company’s strategy execution. The board’s scorecard had four main perspectives—learning and growth, internal, stakeholder, and financial. The internal perspective included three main processes—performance oversight, executive enhancement, and compliance and communication. For performance oversight, the board created measures related to approving strategies and overseeing execution and approving and monitoring funding for strategic initiatives. The executive enhancement measures focused on evaluating and rewarding executive performance and overseeing succession planning for key positions. The compliance and communication measures related to ensuring clear and reliable corporate disclosures and actively monitoring risk and regulatory compliance. Source: Robert S. Kaplan and Michael Nagel, “First Commonwealth Financial Corporation,” Harvard Business School Publishing, 2003, pp. 1–30. LEARNING OBJECTIVE 6 Some Measures of Internal Business Process Performance Compute delivery cycle time, throughput time, and manufacturing cycle efficiency (MCE). Most of the performance measures listed in Exhibit 10–11 are self-explanatory. However, three are not—delivery cycle time, throughput time, and manufacturing cycle efficiency (MCE). These three important performance measures are discussed next. Delivery Cycle Time The amount of time from when a customer order is received to when the completed order is shipped is called delivery cycle time. This time is clearly a key concern to many customers, who would like the delivery cycle time to be as short as possible. Cutting the delivery cycle time may give a company a key competitive advantage—and may be necessary for survival. Throughput (Manufacturing Cycle) Time The amount of time required to turn raw materials into completed products is called throughput time, or manufacturing cycle time. The relation between the delivery cycle time and the throughput (manufacturing cycle) time is illustrated in Exhibit 10–14. As shown in Exhibit 10–14, the throughput time, or manufacturing cycle time, is made up of process time, inspection time, move time, and queue time. Process time is the amount of time work is actually done on the product. Inspection time is the amount of time spent ensuring that the product is not defective. Move time is the time required to move materials or partially completed products from workstation to workstation. Queue time is the amount of time a product spends waiting to be worked on, to be moved, to be inspected, or to be shipped. As shown at the bottom of Exhibit 10–14, only one of these four activities adds value to the product—process time. The other three activities—inspecting, moving, and queuing— add no value and should be eliminated as much as possible. /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 447 12/25/06 3:32:41 PM epg1 Standard Costs and the Balanced Scorecard 447 E X H I B I T 10–14 Delivery Cycle Time and Throughput (Manufacturing Cycle) Time Customer’s Order Received Production Started Wait Time Goods Shipped Process Time + Inspection Time + Move Time + Queue Time Throughput (Manufacturing Cycle) Time Delivery Cycle Time Value-Added Time Non-Value-Added Time Process Time Wait Time Inspection Time Move Time Queue Time Manufacturing Cycle Efficiency (MCE) Through concerted efforts to eliminate the non-value-added activities of inspecting, moving, and queuing, some companies have reduced their throughput time to only a fraction of previous levels. In turn, this has helped to reduce the delivery cycle time from months to only weeks or hours. Throughput time, which is considered to be a key measure in delivery performance, can be put into better perspective by computing the manufacturing cycle efficiency (MCE). The MCE is computed by relating the value-added time to the throughput time. The formula is: MCE Value-added time (Process time) Throughput (manufacturing cycle) time Any non-value-added time results in an MCE of less than 1. An MCE of 0.5, for example, would mean that half of the total production time consists of inspection, moving, and similar non-value-added activities. In many manufacturing companies, the MCE is less than 0.1 (10%), which means that 90% of the time a unit is in process is spent on activities that do not add value to the product. Monitoring the MCE helps companies to reduce non-valueadded activities and thus get products into the hands of customers more quickly and at a lower cost. Example To provide an example of these measures, consider the following data for Novex Company: Novex Company keeps careful track of the time to complete customer orders. During the most recent quarter, the following average times were recorded for each unit or order: Days Wait time . . . . . . . . . . . Inspection time . . . . . . . Process time . . . . . . . . Move time . . . . . . . . . . Queue time . . . . . . . . . 17.0 0.4 2.0 0.6 5.0 Goods are shipped as soon as production is completed. /Volumes/201/MHIY010/mhgar12/gar12ch10 CONFIRMING PAGES gar26703_ch10_417-473.indd Page 448 12/25/06 3:32:41 PM epg1 448 Chapter 10 Required: 1. 2. 3. 4. Compute the throughput time. Compute the manufacturing cycle efficiency (MCE). What percentage of the production time is spent in non-value-added activities? Compute the delivery cycle time. Solution 1. Throughput time Process time Inspection time Move time Queue time 2.0 days 0.4 days 0.6 days 5.0 days 8.0 days 2. Only process time represents value-added time; therefore, the computation of the MCE would be as follows: MCE Value-added time 2.0 days Throughput time 8.0 days 0.25 Thus, once put into production, a typical unit is actually being worked on only 25% of the time. 3. Since the MCE is 25%, 75% (100% − 25%) of total production time is spent in nonvalue-added activities. 4. Delivery cycle time Wait time Throughput time 17.0 days 8.0 days 25.0 days Some Final Observations Concerning the Balanced Scorecard We would like to emphasize a few points concerning the balanced scorecard. First, the balanced scorecard should be tailored to the company’s strategy; each company’s balanced scorecard should be unique. The examples given in this chapter are just that—examples. They should not be interpreted as general templates to be fitted to each company. Second, the balanced scorecard reflects a particular strategy, or theory, about how a company can further its objectives by taking specific actions. The theory should be viewed as tentative and subject to change if the actions do not in fact result in improvements in the company’s financial and other goals. If the theory (i.e., strategy) changes, then the performance measures on the balanced scorecard should also change. The balanced scorecard should be viewed as a dynamic system that evolves as the company’s strategy evolves. IN BUSINESS DELIVERY CYCLE TIMES IN THE DARK AGES Have you ever ordered a new magazine and counted how many days it took for the first issue to arrive? Chances are that your delivery cycle time was somewhere between four to six weeks—a glacial pace in today’s Internet environment. One of the root causes of the problem is fragmented organizational structures where circulation, fulfillment, production, manufacturing, and distribution focus on their departmental agendas instead of the customer. Most circulation directors agree that removing non-valueadded time from the process of responding to customer orders would certainly have its benefits. For example, customers who receive their first issue of the magazine sooner are likely to pay their bill sooner. Furthermore, they are less likely to cancel their subscription or issue complaints that are costly to resolve. One way to reduce the problem is for publishers to mail the first issue to customers using first class mail rather than periodical mail. This would shave six to seven days off of their delivery cycle time, but it would also cost an extra 80 to 90 cents for each first issue mailed. Do you think the time saved is worth the money spent? Source: William B. Dugan, “Thanks for Ordering our Magazine . . . Now Don’t Expect to See It for Five Weeks,” Circulation Management, May 1, 2004, pp. 24–29.