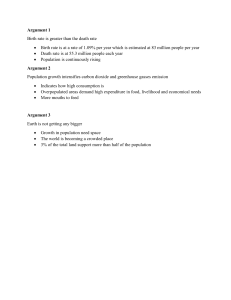

Critiquing Arguments What has been sketched out so far provides only a brief account of the basics of philosophical argumentation. However, if one takes on board all the lessons from it, one is provided with a wide range of tools for the critique of arguments. First, one can show that the argument depends upon a false premise. This attacks the argument at its root and prevents it from getting off the ground. Sometimes, it is necessary to show that a premise is actually false. On the other occasions, it can be enough to show that the premise has not been established. For instance, if one wants to argue that baboons should be granted full human rights because they demonstrate the capacity for abstract thought, the argument fails if the truth of the premise has not been established. One doesn’t need to show that baboons don’t have the capacity for abstract thought, it is enough to show that it has not been established that they do. (The argument that we should grant baboons full human rights because they might have the capacity for abstract thought is importantly different.) Second, one can show that the argument depends upon a premise which has not been recognised and is either false or not established as true. For example, in the baboon argument, it may simply have been assumed by the person putting forward the argument that full human rights should be granted to creatures that can demonstrate the capacity for abstract thought. If this is so, then the argument rests on an unstated and unrecognised premise. The critic can then show that this premise is in fact necessary for the argument to work and then show that it is either false or has not been shown to be true. Third, if the argument is deductive in structure, one can show that the argument is invalid. One does this by showing that the premises do not guarantee the truth of the conclusion. For example, someone might argue: If John got drunk last night, he’ll look a wreck this morning. John looks a wreck this morning. Therefore, John got drunk last night. This can be shown to be invalid because it is possible that both premises are true yet the conclusion is false. For instance, it may be true that John always looks a wreck in the morning if he gets drunk the night before and that John looks a wreck this morning, but in this instance he looks terrible because his neighbour kept him awake all night playing Elvis Costello albums at full volume, not because he was drunk. Therefore the argument is invalid. (Note that the argument is invalid even if, as a matter of fact, John did get drunk last night. The point is the conclusion doesn’t follow on from the premises and so is not necessarily true, not that that it is necessarily false, i.e. the conclusion isn’t rigorous and leaves room for different possibilities). Forth, in an inductive argument one can show that the premises do not provide sufficient evidence for the conclusion. If I reason that everyone who has ever lived has died and therefore I too will die, this is a justifiable inference. But I reason that therefore everyone called Simon is an arrogant fool, this is clearly not a justifiable inference. What makes an inductive inference justifiable is a matter of debate, but it essentially hinges upon the argument being based on the kind of evidence which can reliably be generalized from. A limited acquaintance with a few people with the same name is not the kind of evidence from which one can generalise to all people with the same name. Fifth, in an abductive argument one can argue that there is a better explanation than the one offered. One can do this by showing that the alternative explains more, relies on fewer coincidences or makes fewer assumptions, for example. In the crop circles example, the explanation that winds caused the circles requires one to suppose that freak weather caused some remarkably intricate patterns to be created. That seems as likely as imagining that a great abstract painting was caused by chance spillages of some paint buckets. The explanation that hoaxers did it explains more because it explains not only the appearance of the circles, but also their intricate design. Sixth, one can argue that an inappropriate or inadequate form of justification has been used. Different issues call for different types of argument. In some cases the firm proof of a deductive argument may be needed, but only an inductive argument is offered. This is most evident when someone is offering an argument as a firm proof but the argument fails to be deductively valid. One might also criticise someone for trying to provide a deductive argument when the subject matter demands an inductive one. Matching the right form of argument to the right issue is a skill as important as constructing one’s arguments well. Summary Deductive 1. Show that the premise is false. 2. Show that the premise has no been proven yet. 3. Although the premises are all correct, they don’t necessarily follow on to the conclusion (i.e. other conclusions could be made.) Inductive 4. The premises don’t provide clear enough evidence. The conclusion is only justifiable if, it can be inferred from a lot of past experience; not just one or two experiences. Abductive 5. Is there an alternative conclusion that fits better with the evidence given? General 6. Is the right argument being put forward? For example, someone might put forward an inductive argument when the conclusion is abductive (i.e. cannot be known) – Swinburne’s argument for religious experience proving God’s existence is abductive, yet he suggests that it is inductive.