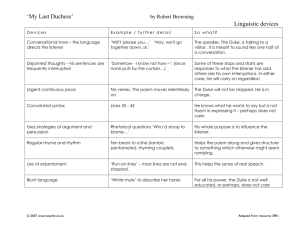

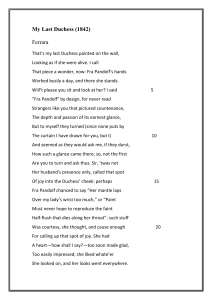

My Last Duchess Robert Browning 1812 - 1889 the VICTORIAN era Queen Victoria ❑ Named after the reining monarch, Queen Victoria, who ruled Great Britain from 1837 – 1901. Her reign is often associated with strict social conventions, sexual restraint and prudishness. ❑ Literature of the time was governed by similarly strict conventions. Victorian writers and audiences favoured realism over the imagination and fantasy emphasised by the Romantics. ❑ The period was characterised by peace; economic prosperity; positive political reforms; a strong sense of British nationalism; more widely available education, especially for girls; rapid progress in science, medicine, commerce and manufacturing; and an expansion in Britain’s territorial acquisitions overseas. the VICTORIAN era cont. ❑ The Industrial Revolution caused rapid urbanisation, which led to severe social problems: overcrowding and unhygienic slums; hunger and malnutrition; lack of sanitation and rapidly-spreading, deadly diseases such as typhoid, cholera and tuberculosis; unemployment and rampant crime; prostitution and child labour – as chimney sweeps, in factories and mines … ❑ Victorian poets are often viewed as the chroniclers of their day, reflecting the social conditions and concerns of the era. ❑ The authority of religion continued to be eroded and one of the key themes of poetry in this era was the relationship between religion and science. Another theme was the power of nature. Queen Victoria the VICTORIAN era Queen Victoria cont. ❑ The Industrial Revolution and its consequences, including the polarisation of English society into a wealthy middle and upper class and a larger poor population, was another theme. ❑ Some poets chose not to engage with this tension, instead drawing from classical and neoclassical literature and mythology, rather than from the realities of urban life. ❑ As the century progressed, many writers – most notably Matthew Arnold, who wrote “Dover Beach” – began to show features of what would become the Modernist movement in their poetry. ❑ As women’s access to education and involvement increased, more and more women began to publish their writing, introducing new voices an perspectives to the reading public and paving the way for future female writers. about the poet ❑ Born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father, who worked as a bank clerk, was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. Much of Browning's education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. ❑ In 1828, Browning enrolled at the University of London, but he soon left, anxious to read and learn at his own pace. The random nature of his education later surfaced in his writing, leading to criticism of his poems' obscurities. ❑ In 1833, Browning anonymously published his first major published work, Pauline, and in 1840 he published Sordello, widely regarded as a failure. He also tried his hand at drama, but his plays, including Strafford and the Bells and Pomegranates series, were for the most part unsuccessful. Robert Browning about the poet cont. ❑ Nevertheless, the techniques he developed through his dramatic monologues—especially his use of diction, rhythm, and symbol— are regarded as his most important contribution to poetry, influencing such major poets of the twentieth century as Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and Robert Frost. ❑ After reading Elizabeth Barrett’s Poems (1844) and corresponding with her for a few months, Browning met her in 1845. They married in 1846, against the wishes of Barrett's father. The couple moved to Pisa and then Florence, where they continued to write. They had a son, Robert "Pen" Browning, in 1849, the same year his Collected Poems was published. Elizabeth inspired Robert's collection of poems Men and Women (1855), which he dedicated to her. Now regarded as one of Browning's best works, the book was received with little notice at the time; its author was then primarily known as Elizabeth Barrett's husband. Elizabeth Barrett about the poet cont. ❑ Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in 1861, and Robert and Pen Browning soon moved to London. Browning went on to publish Dramatis Personae (1864), and The Ring and the Book (1868– 1869). The latter, based on a seventeenth-century Italian murder trial, received wide critical acclaim, finally earning a twilight of renown and respect in Browning's career. ❑ The Browning Society was founded while he still lived, in 1881, and he was awarded honorary degrees by Oxford University in 1882 and the University of Edinburgh in 1884. ❑ Robert Browning died in Venice, Italy, while visiting a friend, on the same day that his final volume of verse, Asolando: Fancies and Facts, was published, in 1889. Robert Browning https://poets.org/poet/robert-browning setting and background Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara ❑ The setting of "My Last Duchess” is the palace of the Duke of Ferrara on a day in October 1564. Ferrara, a city in northern Italy, was the seat of an important principality ruled by the House of Este from 1208 to 1598. The Este family made Ferrara an important centre of arts and learning, supporting the work of such painters as Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael. ❑ Historians believe that in Browning’s poem, the Duke of Ferrara is modeled after Alfonso II, the fifth and last duke of the principality, who ruled Ferrara from 1559 to 1597 but in three marriages fathered no heir to succeed him. The deceased duchess in the poem was his first wife, Lucrezia de Medici, a daughter of Cosimo de Medici (1519-1574). setting and background ❑ The Duke married his first wife, Lucrezia, when she was only 14, and he was 25. It is believed that he married her for her dowry. She died when she was only 17, allegedly after being poisoned by the Duke, who married the daughter of Emperor Ferdinand I soon after. Alfonso II d’Este, Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara Duke of Ferrara Lucrezia de Medici characters ❑ Speaker (or Narrator): The speaker is the Duke of Ferrara. The poem reveals him as a proud, possessive, and selfish man and a lover of the arts. He regarded his late wife as a mere object who existed only to please him and do his bidding. He likes the portrait of her (the subject of his monologue) because, unlike the duchess when she was alive, it reveals only her beauty and none of the qualities in her that annoyed the duke when she was alive. Morever, he now has complete control of the portrait as a pretty art object that he can show to visitors. Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara The poem can thus also be read as a commentary on the values of Renaissance society, which held onto the notion of the ‘ideal man’, such as the duke, who collected works of art – considered to be the mark of an erudite and civilised gentleman. Browning’s version reveals the duke as anything but “ideal”. characters cont. ❑ Duchess: The late wife of the duke. The duke says the duchess enjoyed the company of other men and implies that she was unfaithful. Whether his accusation is a fabrication is uncertain. The real duchess died under suspicious circumstances on April 21, 1561, just two years after he married her. She may have been poisoned. ❑ Emissary of the Count of Tyrol: The emissary/ envoy (a messenger or representative) has no speaking role; he simply listens as the Duke of Ferrara tells him about the late Duchess of Ferrara and the fresco of her. Historically, the emissary is identified with Nikolaus Madruz, of Innsbruck, Austria. ❑ Count of Tyrol: The father of the duke's bride-to-be. The duke mentions him in connection with a dowry the count is expected to provide Lucrezia de Medici characters cont. ❑ Daughter of the Count of Tyrol. The duke's bride-to-be is the daughter of the count but appears to be modeled historically on the count's niece, Barbara, daughter of Emperor Ferdinand I. ❑ Frà Pandolph: The duke mentions him as the artist who painted the fresco. No one has identified a real-life counterpart on whom he was based. He may have been a fictional creation of Browning. Frà was a title of Italian friars of the Roman Catholic Church. ❑ Claus of Innsbruck: The duke mentions him as the artist who created "Neptune Taming a Sea-Horse." Like Pandolph, he may have been a fictional creation. Lucrezia de Medici poem summary and commentary ❑ Upstairs at his palace in October of 1564, the Duke of Ferrara shows a portrait of his late wife, who died in 1561, to a representative of the Count of Tyrol, an Austrian nobleman. The duke plans to marry the count’s daughter after he negotiates for a handsome dowry from the count. ❑ While discussing the portrait, the duke also discusses his relationship with the late countess, revealing himself – probably unwittingly – as a domineering husband who regarded his beautiful wife as a mere object, a possession whose sole mission was to please him. His comments are sometimes straightforward and frank and sometimes subtle and ambiguous. Several remarks hint that he may have murdered his wife, just a teenager at the time of her death two years after she married him, but the oblique and roundabout language in which he couches these remarks falls short of an open confession. poem summary and commentary cont. ❑ The duke tells the Austrian emissary that he admires the portrait of the duchess but was exasperated with his wife while she was alive, for she devoted as much attention to trivialities – and other men – as she did to him. He even implies that she had affairs. In response to these affairs, he says, “I gave commands; / “Then all [of her] smiles stopped together.” ....... Does “commands” mean that he ordered someone to kill her? ....... Does it mean he reprimanded her? ....... Does it mean he ordered some other action? ❑ The poem does not provide enough information to answer these questions. Nor does it provide enough information to determine whether the duke is lying about his wife or exaggerating her faults. Whatever the case, research into her life has resulted in speculation that she was poisoned. Browning himself says the duke either ordered her murder or sent her off to a convent. poem summary and commentary cont. ❑ That the duke regarded his wife as a mere object, a possession, is clear. For example, in lines 2 and 3, while he and the emissary are looking at the painting, he says, “I call that piece a wonder, now.” “Piece” explicitly refers to the portrait but implicitly refers to the duchess when she was alive. “Now” is a telling word in his statement: It reveals that the duchess is a wonder in the portrait, because of the charming pose she strikes, but implies that she was far less than a wonder when she was alive. ❑ Of course, the engaging pose the duchess strikes is not the only reason the duke prizes the portrait. He prizes it also because the duchess is under his full control as an image on the wall. She cannot play the coquette; she cannot protest or disobey his commands; she cannot do anything except smile out at the duke and to anyone else the duke allows to view the portrait. poem summary and commentary cont. ❑ As the duke and the emissary turn to go downstairs, the duke points out another art object–a bronze art object showing Neptune taming a sea horse. The emissary might well have wondered whether the duke regarded himself as Neptune and the sea horse as the duchess. ❑ What the emissary plans to tell the count about the duke is open to question. But in real life, the duke did marry the woman he discussed with the emissary. the portrait/ objectification and control ❑ The portrait of the late Duchess of Ferrara is a fresco, a type of work painted in watercolors directly on a plaster wall. The portrait symbolises the duke's possessive and controlling nature inasmuch as the duchess has become an art object which he owns and controls. ❑ By retelling the duchess’s story in the form of a dramatic monologue recited entirely by the duke, the poet is suggesting that the duchess is objectified so much that she is literally and metaphorically voiceless – she has no voice to tell her own story or to defend herself and her character. ❑ We do not hear the responses of the duke’s guest and can only infer his reactions to the monologue from the duke’s responses to him, but he seems to defer to his host’s authority; if he has suspicions about the duchess’s death, he doesn’t appear to express them, which makes him complicit in the duke’s deceit. the portrait/ objectification and control ❑ The theme of objectification is extended by framing the poem so that it begins and ends with the duke describing two works of art in his collection: the painting of the duchess and a bronze statue of Neptune. The subject of the statue is a patriarchal male figure, dominating the natural world, which encourages the reader to interpret the duchess’s story as a similar story of patriarchal values and male domination. This comparison also suggests that the painting of the duchess has the same value to the duke as the statue, even though the painting of a deceased wife should have more sentimental value. ❑ A contemporary feminist reading of the poem argues that there is an implicit threatened violence in the poem that reflects the divide between the genders that still prevailed in Browning’s lifetime. This interpretation emphasises that Victorian women were still objectified – they had few rights and married women were legally controlled or “subsumed” by their husbands until the law changed in 1882. This type of objectification could be seen as an insidious form of domestic violence because it prevented women from being independent and from leaving abusive relationships. type of work: poem as dramatic monologue ❑ "My Last Duchess" is a poem in the form of a dramatic monologue. A dramatic monologue presents a moment in which the main character of the poem discusses a topic and, in so doing, also reveals his personal feelings to a listener. Only the main character, called the speaker, talks– hence the term monologue, meaning single (mono) speaker who presents spoken or written discourse (logue). ❑ During his discourse, the speaker makes comments that reveal information about his personality and psyche, knowingly or unknowingly. The main focus of a dramatic monologue is this personal information, not the topic which the speaker happens to be discussing. meter and rhyme ❑ Meter "My Last Duchess" is in iambic pentameter (10 syllables, or five feet, per line with five pairs of unstressed and stressed syllables), as lines 1 and 2 (less so) of the poem demonstrate. That's MY | last DUCH | ess PAINT | ed ON | the WALL, Look ING | as IF | she WERE | a LIVE | I CALL ❑ Rhyme: Heroic Couplets Line 1 rhymes with line 2, line 3 with 4, line 5 with 6, and so on. Pairs of rhyming lines are called couplets. When the lines are written in iambic pentameter, as are the lines of "My Last Duchess," the rhyming pairs are called heroic couplets. structure and rhythm ❑ The structure of the poem, together with the use of iambic pentameter, mimics the rhythm of speech. It comprises only one stanza of 56 lines. ❑ The lines of the poem ramble, with thoughts often introduced midsentence, in much the same way as ordinary speech does. A number of lines are enjambed e.g. line 2 runs on into line 3 with no punctuation to interrupt the flow of meaning, again, much as in a conversation. ❑ There are a number of interjections such as “I know not how” in line 32, which are punctuated with dashes and ellipses, replicating the flow and pattern of speech. ❑ The flow of the duke’s speech suggests his suaveness and sophistication as he explains what he sees as his very reasonable objections to his wife’s “misbehavior” (her flirtatiousness and insistence on treating others as equals, and her apparent infidelity). It also underscores his preoccupation with himself, his social status and his sense of superiority. The use of the possessive adjective is significant. Some modern critics have suggested that this suggests the possessive nature of the duke, and that the poem is Browning’s critique not only of the story that inspired the poem, but also of the way women were treated in Victorian England. the title My Last Duchess Ferrara Browning included this almost like a subheading in his original poem, but most anthologies leave it out now. This is the name of an Italian town and this is how historians have made the link to Alonso II. Ambiguous: ❑ he’s had a string of wives ❑ his wife is dead the poem diction indicates his wife as a wonder in the painting but something less when she lived This pronoun refers to an object (compare it to “She’s my last duchess”). no differentiation between person and painting – objectification This again blurs the distinction between the painting and the woman it represents – more objectification 5 fresco – a painting executed on wet plaster That's my last Duchess painted on the wall, Looking as if she were alive. I call That piece a wonder, now: Frà Pandolf's hands Worked busily a day, and there she stands. Will't please you sit and look at her? I said more objectification. He refers to the painting as “her”, again showing his inability to distinguish between the two The painting is a good one and the duke is vulgarly bragging (namedropping) here – he mentions Frà Pandolf by name, and repeats it, so we assume he was well known. Frà = monk/ religious figure. Translates as “Brother”. This is important because it makes the duke’s accusation that there was something going on between his wife and the painter all the more unlikely. the poem on purpose People who see the painting are so in awe that they turn to the duke but then stop themselves in time from asking how this expression came to be on the duchess’s face 10 "Frà Pandolf" by design, for never read Strangers like you that pictured countenance, The depth and passion of its earnest glance, But to myself they turned (since none puts by The curtain I have drawn for you, but I) This shows the controlling nature, arrogance and self-importance of the duke; he is the only person with the power to draw aside the curtain that reveals the painting of the duchess – not everyone has the privilege of viewing it. face The duke is praising the skill of the artist. He likes the painting but later reveals that he did not like the duchess herself. durst = dared This interjection implies that most of his guests are usually too intimidated by him and his social status to have the courage to ask him about the reason for the duchess’s expression you are not the first to ask me this 15 the poem And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, How such a glance came there; so, not the first Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, 'twas not Her husband's presence only, called that spot Of joy into the Duchess' cheek: perhaps i.e. blush We might see this as an endearing naïvety, but he sees it as a blemish on her character. Note the good example of enjambment here Note how the duke’s comments begin innocently but quickly turn sinister the poem cloak or cape 20 Frà Pandolf chanced to say "Her mantle laps Over my lady's wrist too much," or "Paint Must never hope to reproduce the faint Half-flush that dies along her throat”; such stuff Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough The compliments of the painter were uttered out of courtesy, and the duke alleges that the duchess perceived them as more, hence her blush. It’s worth reminding ourselves here that this was a young girl, not yet an adult. This interjection is manipulatively dramatic. He is giving the impression that he is trying to find the right words but this is a carefully rehearsed speech The irony of this list is that it indicates positive qualities that will more likely endear the duchess to the readers, rather than make them critical. The effect is to highlight the duke’s irrationality. 25 the poem For calling up that spot of joy. She had A heart … how shall I say? … too soon made glad, Too easily impressed; she liked whate'er She looked on, and her looks went everywhere. Sir, 'twas all one! My favour at her breast, it was all the same i.e. she didn’t prize one thing more highly than another He now gives a list of examples of all the things that she responds to with equal enthusiasm, beginning with his “favour” i.e. everything she saw made her happy, and she looked at everything alliteration emphasises the trivial nature/ lack of substance of most of the things that drew the duchess’s admiration The reference to the branch of cherries is a double entendre or double meaning, the second of which has sexual connotations. The duke’s accusations are becoming increasingly nasty 30 the poem The dropping of the daylight in the West, officious = intrusive, meddlesome The bough of cherries some officious fool Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule She rode with round the terrace―all and each Would draw from her alike the approving speech, He completes the list of examples of all the things that draw the same words of approval, or blush, from the duchess. Instead of strengthening the duke’s argument, these lines weaken it by suggesting that the Duchess was a kind, thoughtful and perhaps naïve person who appreciated the small things in life. By contrast the duke shows himself to be, at the least, narcissistic and jealous. more evidence that he is proud and pretentious – stooping is beneath him, so he refuses to engage with the duchess on this pettiness 35 He accuses his late wife of being flirtatious and perhaps even promiscuous, even though so far the only evidence he can provide for this is the painting. the poem Or blush, at least. She thanked men,―good; but thanked Somehow … I know not how … as if she ranked My gift of a nine hundred years old name With anybody's gift. Who'd stoop to blame This sort of trifling? Even had you skill It becomes clear that the duchess’s true crime was not being flirtatious and promiscuous, but treating the duke the same way she treated everyone else. It offends the duke’s inflated sense of his own importance when she ranks his “gift” of an old and well-established name and title (he comes from an old aristocratic family named Este) in the same category as the gifts she receives from everyone else. even if one possessed the skill of public speaking … even if one has the skill of public speaking … 40 ―which I have not― Note the interjection in parenthesis. This is false modesty: he is probably quite proud of his skills and is extremely articulate and a skilled manipulator. The iambic pentameter and dramatic monologue form make this parenthesis ironic i.e. his flirtatious and inappropriate wife In speech―(which I have not)―to make your will Diction in these lines Quite clear to such an one, and say, "Just this reveals his paternalistic and Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, superior attitude: he feels he has the right Or there exceed the mark"―and if she let to point out to the duchess the flaws in Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set her that “disgust” him, and to educate (“lesson”) his wife, as one would teach a child, on where she is going right or wrong. But he never actually confronts her He expects that she will learn to think as he does – he will not permit any independent thought or disagreement. Remember that Browning himself married Elizabeth Barrett, who was, at the time, a more successful poet than he. The poet was not threatened by his wife’s intellect or independence, neither did he expect her thoughts to mirror his – but this relationship was unusual for Victorian England, suggesting again that this poem is Browning’s critique of the treatment of women in the poet’s own time. This word “stoop” has already appeared (line 34). The repetition further the entrenches the pompousness and pretentiousness of his tone and demeanour. His pride prevents him from “stooping” to tell the duchess that her behaviour is unacceptable to him. 45 truthfully; in truth Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse, ―E'en then would be some stooping; and I choose Never to stoop. Oh sir, she smiled, no doubt, Whene'er I passed her; but who passed without Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands; Short, curt clauses introduce an even more sinister tone. We assume that she continued to be friendly to everyone she met and instead of addressing this with her, he “gave commands” – to kill her? This increases our sympathy for the duchess, who seems to have a genuinely friendly and happy disposition, making the duke’s expectation that she smile exclusively at him, all the more insecure, irrational and disturbing Another short, curt clause with a sinister tone. It is again not stated unequivocally that he killed her The juxtaposition of “As if alive” with the previous two sentences hints very heavily of foul play 50 the poem Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands As if alive. Will't please you rise? We'll meet munificence = generosity The company below, then. I repeat, We learn that one of The Count your master's known munificence the guests waiting downstairs is the Is ample warrant that no just pretence “Count” (believed to be The duke’s quick switch to a new subject is even more sinister. There is none of the reflective silence that one might expect from a man who has lost his wife, suggesting again that the duchess was simply another possession, like her painting, but far more troublesome. Or perhaps he has realised that he has shared too much information? Emperor Ferdinand I) who is visiting to dicsuss the duke’s marriage proposal. He doesn’t disguise his financial interests in the match and the dowry involved … SEE NEXT SLIDE FOLLOW THE BROWN HIGHLIGHTING FROM THE PREVIOUS SLIDE The duke is prepared to guarantee that the Count, in his generosity, will not refuse to honour the duke’s dowry request. The duke’s undisguised financial interests further cement the reader’s suspicions that the duke had his last wife murdered. He back-pedals here, saying that actually it’s not the money, but the “fair daughter’s self” that is most important. His diction suggests that this wife will be another possession, as indicated by the possessive adjective “my” and the noun “object” (objective i.e. aim) the poem Interesting parallel to the duke’s own behaviour: taming a sea-horse as the duke tried to tame his wife 55 mine for dowry will be disallowed; Though his fair daughter's self, as I avowed At starting, is my object. Nay, we'll go Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though, Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity, Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me! Here he points out another work of art in his collection: a statue of the Roman god of the sea. As at the beginning of the dialogue, the duke explains the value of the work and drops in the name of another famous artist – more vulgar bragging. Beginning and ending the monologue like this emphasises his superficiality – seeing no difference, in his mind, between these two artworks.