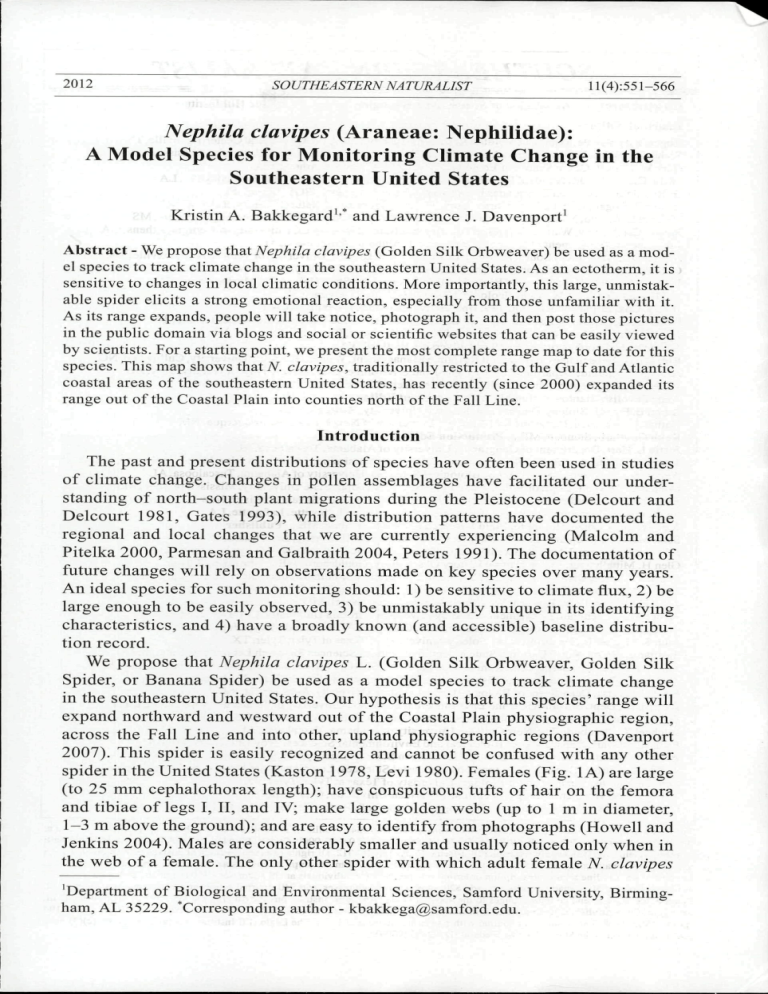

2012 SOUTHEASTERN NATURALIST ll(4):551-566 Nephila clavipes (Araneae: Nephilidae): A Model Species for Monitoring Climate Change in the _ Southeastern United States " Kristin A. Bakkegard'* and Lawrence J. Davenport' Abstract - We propose that Nephila clavipes (Golden Silk Orbweaver) be used as a model species to track climate change in the southeastern United States. As an ectotherm, it is sensitive to changes in local climatic conditions. More importantly, this large, unmistakable spider elicits a strong emotional reaction, especially from those unfamiliar with it. As its range expands, people will take notice, photograph it, and then post those pictures in the public domain via blogs and social or scientific websites that can be easily viewed by scientists. For a starting point, we present the most complete range map to date for this species. This map shows that A^. clavipes, traditionally restricted to the Gulf and Atlantic coastal areas of the southeastern United States, has recently (since 2000) expanded its range out of the Coastal Plain into counties north of the Fall Line. Introduction .v .„„j.,;,..:,. The past and present distributions of species have often been used in studies of climate change. Changes in pollen assemblages have facilitated our understanding of north-south plant migrations during the Pleistocene (Delcourt and Delcourt 1981, Gates 1993), while distribution patterns have documented the regional and local changes that we are currently experiencing (Malcolm and Pitelka 2000, Parmesan and Galbraith 2004, Peters 1991). The documentation of future changes will rely on observations made on key species over many years. An ideal species for such monitoring should: 1) be sensitive to climate flux, 2) be large enough to be easily observed, 3) be unmistakably unique in its identifying characteristics, and 4) have a broadly known (and accessible) baseline distribution record. We propose that Nephila clavipes L. (Golden Silk Orbweaver, Golden Silk Spider, or Banana Spider) be used as a model species to track climate change in the southeastern United States. Our hypothesis is that this species' range will expand northward and westward out of the Coastal Plain physiographic region, across the Fall Line and into other, upland physiographic regions (Davenport 2007). This spider is easily recognized and cannot be confused with any other spider in the United States (Kaston 1978, Levi 1980). Females (Fig. 1 A) are large (to 25 mm céphalothorax length); have conspicuous tufts of hair on the femora and tibiae of legs I, II, and IV; make large golden webs (up to 1 m in diameter, 1-3 m above the ground); and are easy to identify from photographs (Howell and Jenkins 2004). Males are considerably smaller and usually noticed only when in the web of a female. The only other spider with which adult female N. clavipes 'Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Samford University, Birmingham, AL 35229. 'Corresponding author - kbakkega@samford.edu. 552 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 11, No. 4 could be confused with by an untrained eye is Argiope aurantia Lucas (Blackand-Yellow Argiope or Garden Spider). However, A. aurantia has a rounder, less angular body and no hairy tufts on its legs (Fig. 1B); in addition, it does not have a golden-yellow web, and its web often contains a stabilimentum, which inspires another common name, the Writing Spider (Howell and Jenkins 2004). Spiders are ectotherms and thus are highly influenced by their microclimate (especially temperature and humidity), local weather, and large-scale climatic trends (Pulz 1987). Globally, the genus Nephila is restricted to tropical climes, with A'^. clavipes as the only species found in the Americas, from Argentina to the southeastern United States (Kuntner et al. 2008, Levi 1980). Its nothern range limit in the continent is currently in the southern portion of the southeastern US (Fig. 2). Therefore, its northward expansion will be limited by winter conditions, since tropical spiders are more likely to be injured by cold weather. However, spider eggs in general appear to be highly (to -24 °C) resistant to cold (Kirchner 1987). In winter, female N. clavipes behaviorally thermoregulate by sun-basking. They can elevate their body temperature during the daytime 7 °C above ambient air temperature and will change the orientation of their webs to maximize insolation (Carrel 1978). At temperatures below 10 °C, A^. clavipes becomes inactive. Figure 1. Photographs of similar spiders found in the southeastern United States: A. Female Nephila clavipes. Note the rectangular abdomen and distinctive leg tufts. The web is also distinctively yellow (not seen in photo). B. Female Argiope aurantia. Note the rounded abdomen and no leg tufts. Webs usually have a stabilimentum (thicker, zig-zag portion seen running down center of photo under spider). Both photographs, by W.M. Howell, were taken in Geneva County, AL, and are used with permission. ^,,., 2012 K.A. Bakkegard and L..I. Davenport 553 while temperatures below 0 °C are fatal to adults (Moore 1977). In the sumtner, if exposed to direct sun, the spider thermoregulates by making postural adjustments in its web (Higgins and Ezcurra 1996, Robinson and Robinson 1974). As temperatures increase, individuals will perform evaporative cooling behaviors at 36.78 °C; death occurs at 41.65 °C (Krakauer 1972). Being a tropical species, A^. clavipes prefers a relative humidity greater than 80% (Moore 1977). In temperate zones, adult Nephila clavipes have a life span of one year (Moore 1977). Females make 1 to 5 egg sacs during that year, with the average number of eggs per clutch ranging from 338.3 ± 117.8 to 585.8 ± 249.0, depending on the deposition date (Higgins 1992, Moore 1977). Females deposit clutches anywhere from September through November (Moore 1977, Wilder 1865). This spider overwinters as eggs and spiderlings, which stay in the egg case 5-7 months until emerging sometime between mid-spring to June to form a communal web, molt, and then disperse (Higgins 2000, Hill and Christenson 1981, Moore 1977). Females mature in 3-5 months (8-10 instars), whereas males mature earlier (3-5 instars) and with a significantly smaller body size (Higgins 2000, Higgins and Goodnight 2010). Juvenile males make their own webs for prey capture until their final molt. Then within 3 days, they abandon their webs to search for females (Myers and Christenson 1988). Males often co-habitat with females, and A^. clavipes webs often contain kleptoparasites (Agnarsson 2003). o • 1863 — I 9 6 0 1961 — 1999 2000 - 2 0 1 1 _ _ / ^ ^ ^ ^ [^^JTM^^^^^^^^Cha rieston 1 1 H i 1 ire 1 Orleans ^ ? B ^ 3uston Figure 2. Range of Nephila clavipes in the continental United States (one 1965 Arizona record and one 1935 California record not shown). Dates indicate the earliest record for the spider. Solid line indicates the Fall Line which delineates the coastal plain from interior physiographic regions. Counties with no records are in white. 554 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 11, No. 4 Presumably, like many other spiders, Nephila clavipes is capable of ballooning (Decae 1987). In Simberloff and Wilson's (1969) classic study of recolonization on mangrove islands, A^. clavipes easily recolonized the emptied islands, apparently by aerial transport. However, it is difficult to determine, based on the literature, if ballooning is their primary mode of dispersal. Glick (1939) did not list Nephila in his study ofthe aerial arthropods over Tallulah, LA (Madison Parish), but over 900 spiders in that study were left unidentified. Kuntner and Agnarsson (2011) show that as a genus, Nephila is an excellent colonizer and suggest ballooning as the most likely method of dispersal, although it has not yet been observed to do so. Additionally, N. clavipes may use an intermediate form of ballooning, where the spiderling makes a silk thread that is floated in the air; when the thread contacts a structure, the line is made fast and the spider walks across (Moore 1977). .J'.v'Ji Materials and Methods 'f^^ :•• '" In order to fully document the current distribution of Nephila clavipes, we searched for distributional records in the published literature (including early natural history narratives going back to 1768), natural history museum collections, and online databases, and solicited observations from experienced field biologists. We examined specimens from the American Museum of Natural History, Florida State Collection of Arthropods, and the National Museum of Natural History. We also performed Google searches to find blogs, looked at social photograph-posting websites such as Flickr, Pbase, Photobucket, Picasa, and YouTube, and used entomology and hobby-oriented websites such as Bugguide. net, Dave's Garden, and Spiderzrule. Our last web search was conducted 3 January 2012. For each distributional record, we recorded its source, date, state, county or parish, specific locality (if available), photographer or collector (in the case of specimens), and any additional notes (Bugguide.net proved to be a particularly rich source of natural history notes). By recording the photographer and examining each photograph and associated data, we were able to determine if the photographer had posted multiple views of the same spider, and thus avoided duplicate entries. ,: Results We accumulated 945 records of Nephila clavipes with county-level locality data in the continental United States. To date, A'^. clavipes has been recorded in 204 counties of 11 states (Fig. 2, Appendix 1). Of these records, 50.7% were from website photographs (includes social and science-based), 37.9% were from natural history museum collections, 5.8% from personal communications with other scientists, and 5.6% from the literature. The early writers on the natural history of the southeastern United States failed to record the presence of Nephila clavipes. However, William Bartram (1943), in his report to Dr. John Fothergill on his travels in Georgia and Florida 2012 K.A. Bakkegard and L.J. Davenport 555 during 1773-1774, described a spider that could be N. clavipes. While his large yellow and black streaked spider sounds much like Argiope aurantia, his description includes "their legs very long and armed with prickles of stiff black hair," which is characteristic oí Nephila. He possibly encountered both species but only mentioned one, later mistakenly fusing their traits together. Philip Henry Gosse (1859), after spending nine months of 1838-1839 in Dallas County, AL, did not mention Nephila, even though he described over 120 other terrestrial invertebrates and noted the presence of spiders in mud dauber nests, ¡A The earliest unambiguous record for Nephila clavipes in the United States is by Wilder (1865). In 1863, Dr. Burt G. Wilder was a surgeon in the Union Army stationed on Folly Island, SC, near Charleston. Wilder specifically wrote that he found no mention of his spider in any publications by earlier workers such as Nicholas Hentz (Burgess 1875), who was later considered the father of American arachnology; Hentz spent much of the 1840s in northern and central Alabama (Davenport 2001). Wilder (1867) was fascinated by the spider's strong yellow silk and thought it could be used for some practical purpose. The oldest specimen for which we found a record was collected by the arachnologist George Marx (1838-1895) in 1885 and is likely to be one of the specimens referred to by McCook (1893). As an historical aside, Marx's entire collection, consisting of over 1000 arachnids, was offered up for sale for $1500 less than a year after his death (Riley et al. 1895). McCook (1893) discussed Nephila clavipes (and several related species now understood to be N. clavipes), stating that it had been collected in Louisiana, Texas, and Key West, FL; he also noted that the spider was probably limited to the Gulf Coast and did not appear to be abundant. For what he called JV. wilderi, he stated its range to be "along Southern Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, and southwesterly to Southern California." A detailed species account, including photographs of its web, can be found in Comstock (1920). However, Comstock provided few specifics, stating that it was "widely distributed through the southern states." Equally noteworthy are early twentieth-century studies that do not Mst Nephila clavipes (or any of its synonyms). These include Banks (1900), who collected 133 species of spiders in the southern half of Alabama, mostly from the Auburn (Lee County) and Mobile (Mobile County) areas. Many of these specimens were taken in the autumn, when N. clavipes is most noticeable. Another example is James Emerton's (1902) book, a guide to the common spiders likely to be found from Georgia to as far west as the Rocky Mountains. Bishop and Crosby (1926) did not find the spider while collecting in the Okefinokee Swamp of southern Georgia during the summer of 1912, although there are several specimens from the Okefinokee Swamp, collected in 1912 by persons unknown, in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) collection. They also did not list the spider in their report, which included records from a collection at the Alabama State Museum (now the University of Alabama Natural History Collection) that covered many southeastern states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas; specimens from 1903-1925). Chamberlin and Ivie (1944) reviewed the spiders of Georgia, also including most 556 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 11, No. 4 of South Carolina, parts of north Florida, and a small section of North Carolina. Their review included field work and a re-examination of drawings by British naturalist John Abbot (1751-1840), who lived in what is now Screven County, GA and is believed to have done most of his work on spiders during the late 1700s (Chamberlin and Ivie 1944). Abbot did not include Nephila in his 567 drawings of spiders, and Chamberlin and Ivie (1944) provide only two records: Leon County, FL and Ware County, GA. Both specimens are in fhe AMNH collection. While museum collections provided "hands-on" documentation, websites varied greatly in their information content, with Bugguide.net, Flickr.com, and Spiderzrule.com being the most useful. Hosted by the Iowa State University Department of Entomology, Bugguidc.net encourages a scientific approach to data collection, with many submitters providing interesting natural history notes on the density of webs (often noted if high), prey items, and whether or not the spider had been previously noticed in their area. The geotagging function of Flickr was likewise helpful. Some hobby-oriented websites, such as Dave's Garden, included locality data, which became an important part of the discussion about fhe spider pictured. Other websites were less helpful, with the largest problem being missing locality data. Sites such as Photobuckct, Facebook, and YouTube contained images but no locality data. ^'•'-- : ; :•::. "• • aoi Discussion • '.'u ' i^ ndtlrvEr :\u a, Using historical records, documented specimens and current observations, we have developed the most comprehensive range map oí Nephila clavipes to date. Prior to our study, the most complete map was by Levi (1980), who noted that the spider was found only in the warmer parts of the southeastern United States. His most northern record was in Hyde County, NC; his most northwestern record was from Navajo County, AZ. Our study adds many historical records, most notably, central Alabama by Archer (1940), and shows fhe northward migration of this spider out of what had been an exclusively coastal plain distribution. The earliest records of this spider are centered on major seaports. Jones (1859) stated that Nephila clavipes (then Epeiria clavipes) was the best known and most attractive spider on Bermuda, and had been known from that island as early as fhe seventeenth century. Since many naturalists of that time, including Charles Darwin (1845), noted the capturing of spiders in ships' sails and riggings, we suggest that the infroduction of N. clavipes fo fhe east Atlantic and Gulf coasts may have been promoted by sailing ships. We can also estimate when fhe spider was infroduced to Alabama. Archer (1940) wrote: "In the last fifteen years, it has established itself in the urban gardens in Mobile, much fo the consternation of the local citizenry. In the last two years if has been invading gardens in Montgomery." Thus, we can dafe fhe introduction of A^. clavipes fo fhe Mobile area between 1900 and 1925 and its northward spread fo Monfgomery by 1938. There are also a few odd records. It is hard to explain fhe Show Low, AZ record (MCZ 25983, hftp://mcz.harvard.edu) collected by F. Matzone in August 1965. Show Low, a cify in east central Arizona, elevafion 1950 m, is in fhe Ponderosa 2012 • K.A. Bakkegard and L.J. Davenport 557 Pine ecosystem and thus experiences cold winter weather. The arachnologist Donald C. Lowrie collected Nephila clavipes in 1935 in California (AMNH collection). The tag states Fillmore County. While there is no Fillmore County in California, there is a city of Fillmore in Ventura County in southern California. Perhaps the spider was introduced via the citrus industry, which brought in plants from all over the world, including Florida and Brazil (Coit 1915), areas where A^. clavipes was already present. Another enigmatic area is northern Mississippi. Dorris and McGaha (1965) included A^. clavipes in their list of spiders from five counties in north central Mississippi, but do not indicate which county contained what species. However, Dorris' (1963) Master's Thesis on which Dorris and McGaha (1965) is based indicates that only one specimen of A^. clavipes was found, in Lafayette County. May's (1933) Thesis and discussions with current Mississippi arachnologists indicate that A^. clavipes is not present, at least in noticeable numbers, in northern Mississippi. It is also clear that southern Mississippi has been under-collected historically. One pitfall that we found in using pictures from the public domain is that the locality data is not always what it seems to be. We found a geotagged photo on Flickr with a locality of Los Angeles, CA. In this case, all the data were correct; it was indeed a photograph oí Nephila clavipes and the photographer was in Los Angeles. However, the photograph was that of A', clavipes on public display in the spider pavilion at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. The second case was of a beautiful photograph posted on the website Dave's Garden with a locality of Greensboro, NC. Unfortunately, the photographer, who lived at the time in Greensboro, has since passed away, so we are unable to confirm that the photograph was actually taken there. Otherwise, that would be an intriguing record, well outside the expected range of this spider. Further studies of this spider should concentrate on these five areas because of their large number of spider records: Houston (Harris County), TX; Charleston (Charleston County), SC; New Orleans (Orieans Parish), LA; Gainesville (Alachua County), FL; and Miami (Miami-Dade County), FL. We recommend monitoring the climate records of each of these areas for future comparisons. In Nephila clavipes, female fecundity significantly increases with larger body size, while later-maturing females are less fecund (Higgins 2000). As the spider expands its range northward, it will encounter stronger seasonality. Thus, we predict a slow spread. However, in the southern parts of its range, eggs and spiderlings should experience a decrease in winter mortality, providing larger source populations. Future documentation of the distribution oí Nephila clavipes will depend on enlisting the public to provide scientific observations. Such efforts can be made formally in the manner of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology with its citizen science program. Or they can be made informally by monitoring websites, such as those devoted to photograph- and video-sharing, social networking, or individual blogs. With range expansion, laypeople unfamiliar with A^. clavipes will soon encounter it for the first time. Because a large spider elicits a strong emotional reaction—either fascination or revulsion—many people will take a picture 558 Southeastem Naturalist Vol. 11, No. 4 or video of the spider and post it online, to share it with others, get it identified, or to determine if it is dangerous. We therefore ask that biologists monitor websites, or whatever means of scientific and social networking will be available, in order to track the spread of this spider. Acknowledgments Thank you to these individuals (listed alphabetically by last name) and institutions that checked collections, loaned specimens, provided locality data from specimens under their curation, or provided locality data from their field notes: J.K. Barnes (University of Arkansas Arthropod Museum), V.M. Bayless (Louisiana State Arthropod Museum), J. Beccaloni (Natural History Museum, London), J.H. Boone (The Field Museum of Natural History), J. A. Coddington (National Museum of Natural History), A. Dean (Texas A & M University), A.R. Diamond (Troy University), G.B. Edwards (Florida State Collection of Arthropods), Z. Falin and J. Thomas (University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute), D.R. Folkerts (Auburn University), J.G. Godwin (Auburn University), H. Guarisco (Sternberg Museum of Natural History), M. Hodge (Louisiana School for Math, Science, and the Arts), W.M. Howell (Samford University), J.G. King (Vanderbilt University), J. Knight (South Carolina State Museum), M.W. LaSalle (Pascagoula River Audubon Center), M.B. Layton (Mississippi State University), J.V. McHugh and C.L. Smith (Georgia Museum of Natural History), P. Miller (Northwest Mississippi Junior College), J.C. Morse and A.B. Harrison (Clemson University Arthropod Collection), G.R. Mullen (Auburn University), M.F. O'Brien (University of Michigan Museum of Zoology), S. Peyton (Mississippi Museum of Natural Science), N.I. Platnik and L.N. Sorkin (American Museum of Natural History), T. Pucci (Cleveland Museum of Natural History), R.J. Pupedis (Peabody Museum of Natural History), J.E. Rawlins (Carnegie Museum of Natural History), C.H. Ray (Aubum University), J.R. Reddell (Texas Memorial Museum), N. Rios (Tulane University Museum of Natural History), T.L. Schiefer (Mississippi Entomological Museum), R.M. Shelley (North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences), K.B. Simpson (Enns Entomology Museum), G. Stratton (University of Mississippi), R. Tumlison (Henderson State University), D. Ubick (California Academy of Sciences), G.M. Ward (University of Alabama), and J.D. Weintraub (Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University). M.E. Martin (LSU Library, Special Collections) assisted in finding an elusive locality. Special thanks to L.N. Sorkin who hosted K.A. Bakkegard's visit to the AMNH collection and the Samford University Interlibrary Loan department. Samford University provided essential funding for this project. - > ' " -• - Literature Cited Agnarsson, I. 2003. Spider webs as habitat patches—The distribution of kleptoparasites (Argyrodes, Theridiidae) among host webs (Nephila, Tetragnathididae). Journal of Arachnology 31:344-349. Archer, A.F. 1940. The Argiopidae or orb-weaving spiders of Alabama. Alabama Museum of Natural History 14:1-41. Banks, N. 1900. Some Arachnida from Alabama. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 52:529-543. Banks, N. 1904. The Arachnida of Florida. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 56:120-147. Bartram, W. 1943. Travels in Georgia and Florida, 1773-74: A Report to Dr. John Fothergill. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 33, part 11:121-242. Reprinted 1996, Penguin Putnam, New York, NY. 701 pp. 2012 - ' K.A. Bakkegard and L.J. Davenport 559 Bishop, S.C., and C.R. Crosby. 1926. Notes on the spiders ofthe southeastern United States with descriptions of new species. Journal ofthe Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 41:165-212. Brown, K.M. 1974. A preliminary checklist of spiders of Nacogdoches, Texas. Journal of Arachnology 1:229-240. Burgess, E. (Ed.). 1875. The spiders ofthe United States: A collection ofthe arachnological writings of Nicholas Marcellus Hentz, M.D. with notes and descriptions by James H. Emerton. Occasional Papers ofthe Boston Society of Natural History II. Boston, MA. 177 pp. with 21 plates. Carrel, J.E. 1978. Behavioral thermorégulation during winter in an orb-weaving spider. Symposium ofthe Zoological Society of London 42:41-50. Chamberlin, R.V., and W. Ivie. 1944. Spiders ofthe Georgia region of North America. Bulletin ofthe University of Utah 35:1-267. Coit, J.E. 1915. Citrus Fruits. The MacMillan Company, New York, NY. 503 pp. Comstock, J.H. 1920. The Spider Book. Doubleday, Page, and Company, Garden City, NY. 721pp. ":/ Darwin, C.R. 1845. Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology ofthe Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. 2nd edition. John Murray, London, UK. 519 pp. Davenport, L.J. 2001. Trapdoor spiders. Alabama Heritage 59:50-52. Davenport, L.J. 2007. Golden silk orbweavers (and climate change). Alabama Heritage 85:54-56. Decae, A.E. 1987. Dispersal: Ballooning and other mechanisms. Pp. 348-356, In W. Nentwig (Ed.). Ecophysiology of Spiders. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. 448 pp. Delcourt, P.A., and H.R. Delcourt. 1981. Vegetation maps for eastern North America: 40,000 yr B.P. to the present. Pp. 123-165, In R.C. Romans (Ed.). Geobotany II. Plenum Press, New York, NY. 263 pp. Dorris, P.R. 1963. Taxonomy, ecology, and distribution ofthe spiders in five counties of northern Mississippi. M.Sc. Thesis. University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS. 164 pp. Dorris, P.R. 1967. The spiders of Mississippi. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS. 283 pp. Dorris, P.R. 1968. A preliminary study ofthe spiders of Clark County, Arkansas, compared with a five-year study of Mississippi spiders. Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings 22:33-37. Dorris, P.R. 1980. A continuation of spider research in Arkansas: Gulf coastal plains. Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings 34:108-112. Dorris, P.R., and Y.J. McGaha. 1965. A list of spiders collected in northern Mississippi. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 84:407-408. Emerton, J.H. 1902. The Common Spiders ofthe United States. Ginn and Company, Boston, MA. 225 pp. Farr, J.A. 1977. Social behavior ofthe Golden Silk Spider, Nephila clavipes (Linnaeus) (Araneae, Araneidae). Journal of Arachnology 4:137-144. Gaddy, L.L., and J.C. Morse. 1985. Common spiders of South Carolina with an annotated checklist. South Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 1094. 166 pp. Gates, D.M. 1993. Climate Change and its Biological Consequences. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. 280 pp. n • .' -" Glick, P.A. 1939. The distribution of insects, spiders, and mites in the air. USDA Technical Bulletin 673. Washington, DC. 150 pp. SÄ Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 11, No. 4 Gosse, P.H. 1859. Letters from Alabama, (US) Chiefly Relating to Natural History. Morgan and Chase, London, UK. (Reprinted 1993, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL). 324 pp. Hardy, L.M. 2010. Additions to the spider fauna of northwestern Louisiana. Southeastern Naturalist 9 (Monograph): 1-40. Higgins, L. 1992. Developmental plasticity and fecundity in the orb-weaving spider Nephila clavipes. Journal of Arachnology 20:94-106. Higgins, L. 2000. The interaction of season length and development time alters size at maturity. Oecologia 122:51-59. Higgins, L.E., and E. Ezcurra. 1996. Mathematical simulation of thermoregulatory behavior in an orb-weaving spider. Functional Ecology 10:322-327. Higgins, L., and C. Goodnight. 2010. Nephila clavipes females have accelerating dietary requirements. Journal of Arachnology 38:150-152. Hill, E.M., and T.E. Christenson. 1981. Effects of prey characteristics and web structure on feeding and predatory responses of Nephila clavipes spiderlings. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 8:1-5. Howell, W.M., and R.L. Jenkins. 2004. Spiders of the Eastern United States: A Photographic Guide. Pearson Education, Boston, MA. 363 pp. Jones, J.M. 1859. The Naturalist in Bermuda: A Sketch of the Geology, Zoology, and Botany, ofthat Remarkable Group of Islands. Reeves and Turner, London, UK. 200 pp. Kaston, B.J. 1978. How to Know the Spiders, 3rd Edition. Wm. C. Brown, Dubuque, IA. 272 pp. Kirchner, W. 1987. Behavioural and physiological adaptations to cold. Pp. 66-77, In W. Nentwig (Ed.). Ecophysiology of Spiders. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. 448 pp. Krakauer, T. 1972. Thermal response of the orb-weaving spider Nephila clavipes. American Midland Naturalist 88:246-250. Kuntner, M. 2003. A preliminary specimen database of true nephiline spiders (Tetragnathidae). Available online at http://www.gwu.edu/~clade/spiders/taxonomyPeet. htm. Accessed 3 January 2012. Kuntner, M., and I. Agnarsson. 2011. Phylogeography of a successful aerial disperser: The golden orb spider Nephila on Indian Ocean islands. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2011, 11:119. Kuntner, M., J.A. Coddington, and G. Horminga. 2008. Phylogeny of extant nephilid orb-weaving spiders (Araneae, Nephilidae): Testing morphological and ethological homologies. Cladistics 24:147-217. Levi, H.W. 1980. The orb-weaver genus Mecynogea, the subfamily Metinae, and the genera Pachygnatha, Glenognatha, and Azilia of the subfamily Tetragnathinae north of Mexico (Araneae: Araneidae). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 149:1-75. Malcolm, J.R., and L.F. Pitelka. 2000. Ecosystems and global climate change: A review of potential impacts on US terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity. Pew Center on Global Climate Change, Arlington, VA. 41 pp. May, U. 1933. Mississippi spiders. M.Sc. Thesis. Mississippi State College, Starkville, MS. 53 pp. McCook, H.C. 1893. American Spiders and their Spinningwork, Volume III. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA. 407 pp. Moore, C.W. 1977. The life cycle, habitat, and variation in selected web parameters in the spider Nephila clavipes Koch (Araneidae). American Midland Naturalist 98:95-108. 2012 K.A. Bakkegard and L.J. Davenport 561 Myers, L., and T. Christenson. 1988. Transition from predatory juvenile male to matesearching adult in the orb-weaving spider Nephila clavipes (Araneae, Araneidae). Journal of Arachnology 16:254-257. Parmesan, C , and H. Galbraith. 2004. Observed impacts of global climate change in the US. Pew Center on Global Climate Change, Adington, VA. 56 pp. Peters, R.L. 1991. Consequences of global warming for biological diversity. Pp. 99-118, In R.L. Wyman (Ed.). Global Climate Change and Life on Earth. Routledge, Chapman, and Hall, New York, NY. 282 pp. Pulz, R. 1987. Thermal and water relations. Pp. 26-55, In W. Nentwig (Ed.). Ecophysiology of Spiders. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. 448 pp. Riley, C.V., L.O. Howard, E.A. Schwartz, and T. Gill. 1895. The Marx collection of Arachnida. Canadian Entomologist 27:272. Robinson, M.H., and B.C. Robinson. 1974. Adaptive complexity: The thermoregulatory postures of the Golden-web Spider, Nephila clavipes, at low latitudes. American Midland Naturalist 92:386-396. Simberloff, D.S., and E.O. Wilson. 1969. Experimental zoogeography of islands: The colonization of empty islands. Ecology 50:278-296. Tumlison, R., and H.W. Robison. 2010. New records and notes on the natural history of selected invertebrates from southern Arkansas. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 64:141-144. Wilder, B.G. 1865. On the Nephilaplumipes, or silk spider, of South Carolina. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History 10:200-210. Wilder, B.G. 1867. Two hundred thousand spiders. Harper's New Monthly Magazine 34:450-466. ,^^ ;arr Vol. 11, No. 4 Southeastern Naturalist 562 Appendix 1. Earliest documented record for Nephila clavipes by state and county (or parish). Number of records is indicated for those counties when the number of records is >5. References are listed in the same order as the counties. If only one reference is listed for multiple counties, then that reference applies to all counties. For pers. comm., the person's initials and affiliation are in the Acknowledgments. For key to other non-literature reference abbreviations, see Appendix 2 below. Earliest record Counties (# of records) Reference AMNH AMNH Archer (1940) 1978 1989 1990 1996 2002 Baldwin (14) Dale (7), Houston, Mobile (10)' Barbour, Covington, Escambia, Montgomery (6), Pike, Tuscaloosa Lee Henry Geneva Coffee Jefferson 2003 2004 2006 Bullock Conecuh, Russell Clarke, Crenshaw, Monroe, Tallapoosa 2008 Choctaw, Lowndes, Wilcox 2009 2010 Autauga, Calhoun, Macon, Perry, Shelby, Washington Elmore AUEM Diamond, pers. comm.^ Diamond, pers. comm. Diamond, pers. comm. Samford University photo voucher Diamond, pers. comm. Diamond, pers. comm. " Diamond, pers. comm. (Clarke, Crenshaw); Folkerts, pers. comm.' (Monroe, Tallapoosa) Ray, pers. comm.* (Choctaw, Lowndes); Diamond, pers. comm. (Wilcox) BG; Ray, pers. comm.; F, BG, BG, F Godwin, pers. comm.' AR 1966 1979 2009 Clark' Union'^ Ashley, Union Dorris (1968) Dorris (1980) Tumlison and Robison (2010) AZ 1965 Navajo MCZ CA 1935 Ventura? AMNH FL 1893 1903 1904 1911 1925 1926 1927 1933 1934 1940 1941 1943 1944 1945 1946 1950 1951 Monroe (48) Miami-Dade (55) Charlotte (5), Citrus Brevard(13) Liberty (9) Alachua (65), Putnam (8)^ St. Lucie (9) Seminóle (9) Lee (9), Leon (16), St. Johns (7) Manatee"", Orange (15) Calhoun, Sarasota (13) Collier (5) Highlands (28), Okaloosa Hendry, Santa Rosa (5) Escambia Osceola Levy (13) Jackson, Pinellas (13) McCook(1893) ; , AMNH Banks (1904) AMNH AMNH AMNH AMNH AMNH USNM, FSCA Archer (1940), AMNH FMNH AMNH Kuntner (2003), AMNH AMNH AMNH FSCA , FSCA , State AL 1932 1939 1940 (; ^ •. • : 2012 State FL GA LA K.A. Bakkegard and L.J. Davenport 563 Earliest record Counties (# of records) Reference 1952 1953 1954 1963 1964 1969 1972 1973 1974 1978 1981 1984 1986 1989 1990 1992 2004 2006 2007 2008 2010 Palm Beach (17) Broward(18) Volusia(8) Columbia, Glades, Marion (17) Martin Indian River Lake(7) Baker WakuUa Jefferson' ': Pasco Hillsborough(13) Holmes DeSoto Gilcrist Gadsden Duval (7), Flagler Hernando Nassau, Polk (7), Sumter, Suwannee Bay, Clay, Union Okeechobee FMNH FMNH FSCA " FSCA FSCA FSCA CAS MCZ Farr(1977) AMNH FSCA Kuntner (2003) Howell, pers. comm.'" FSCA BG NASDB JAX, P 1912 1916 1932 1935 1946 1950 1960 1967 1972 1973 1976 1980 1984 1998 2002 2003 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Unk Charlton (8) Thomas Ware Screven Baker, Ben Hill, Clay Mclntosh (5) Long Liberty Dougherty Bulloch Oconee Glynn (6) Chatham (11) Camden Jasper Bryan, Coffee, Crisp, Lowndes Sumter Tattnall Stewart • Jh.. ^8'. Jones Laurens ' :.ad Clarke AMNH AMNH USNM AMNH FMNH FSCA UGA UGA AMNH ^ Folkerts, pers. comm. FI Smith, pers.comm." 1885 1923 1924 1933 1940 1959 1966 Orleans (11) East Baton Rouge (12) Terrebonne Cameron Jefferson (7) Ascension (5) Jefferson Davis, St. Landry Lee -.iad F -í.'- KM, BG, OBS, F BG, F, F BG USNM , -• AMNH BG GB BG, GB, BG, F P W ' .- • BG • • BG BG Smith, pers. comm. Kuntner (2003) FMNH FMNH Kuntner (2003) AMNH CAS FSCA, LSAM ' :--' ' •; Vol. 11, No. 4 Southeastern Naturalist State LA Earliest record Counties (# of records) Reference 1975 1981 1996 2000s 2004 2005 2007 2008 2009 2011 West Feliciana Plaquemines Bossier Bienville, Natchitoches Livingston St. James Tangipahoa Iberia, St. Tammany, Washington Ouachita, St. Martin (5) St. Charles • - AMNH MCZ Hardy (2010) Hodge, pers. comm.'" SR F 1931 1932 1961 1963 1966 2002 2004 2005 2007 2008 2009 George Jackson (7) Yazoo Lafayette 2011 Hancock, Harrison, Pearl River, Stone 1966 1976 2003 2004 2007 2010 Carteret (8) New Hanover (13) Brunswick (6) Columbus, Onslow Bladen 1863 1935 1953 1977 1978 1985 2004 2005 2006 2009 2010 2011 Charleston (25) Hampton Aiken Beaufort (8) Georgetown (10) Clarendon, Lexington, Orangeburg Horry Jasper, Sumter Berkeley Colleton Dorchester, Richland Barnwell Wilder (1865) AMNH UGCA Gaddy and Morse (1985) CUAC Gaddy and Morse (1985) SR CMNH, SR SR F 1913 1936 1946 1955 1958 1970 1971 1972 Chambers Harris (18) Jefferson Bee Liberty Hardin, Nacogdoches Brazoria, Matagorda Galveston (5) AMNH AMNH MCZ USNM MCZ Brown (1974) NASDB Moore (1977) B G •'& 2 SP, F, BG • £ WTB, F • F • . •• •'" . •..,. '""I" MS NC sc TX • - Jackson :"• • ' • A d a m s - AMNH YPM Dorris (1967) Dorris (1963) " • ' ••' • - -• • BY • ': •"•" ' MEM • "'• .•'•'• ' ' '' Forrest Walthall > Claiborne Greene, Lamar, Noxubee, Perry Clarke, Hinds, Lauderdale, Simpson H y d e ' .. SR - F .. •''• <•' '<»• - F F, B G , F, B G '•• :i^ii" ' -¡-¡SJ'ujA '•• - 1 1. •"' Schiefer, Peyton, Schiefer, Layton - all pers. comm.'^ LaSalle, pers. comm.''' 1 Levi (1980) Levi (1980) NCSP BG NCSP, BG NCSP F F iJ' '•! K.A. Bakkegard and L.J. Davenport State TX 565 Earliest record Counties (# of records) Reference 1980 2004 2005 2007 2009 Willacy Jasper Fort Bend (15) Lavaca, Montgomery, Tyler Brazos NASDB W F SR, BG, F TAMUIC 'USNM has an undated specimen that may have been collected by the arachnologist George Marx, who died 3 Jan 1895. There is a label in the same style and handwriting as another Florida specimen he collected. 'Tumlison & Robison (2010) discusses the validity of these records. 'USNM has an undated specimen (USNM 2055693 -NE 149) collected by G. Marx from this county. "USNM has an undated specimen (USNM 2055693-2754) collected by R.W. Shufeldt (1850-1934). It was likely to have been collected well before 1934. The next most recent record for this county is 2007. 'An undated specimen identified by Levi in 1978. Based on writing style on the tag, it was collected earlier than 1978. There are currently no other records for this county. -:,/> .j-: : •"A.R. Diamond, Troy University, Troy, AL ' ;i,i.' 'D.R. Folkerts, Auburn University, Auburn, AL •'•• > *C.H. Ray, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 'J.G. Godwin, Auburn University, Auburn, AL - • • .. . ••• - '•': ; . - • • ' • • • : ; ; '-,.'.'' '"W.M. H o w e l l , Samford University, H o m e w o o d , A L •; -,. , ,-'• •••,':'' "C.L. Smith, Georgia Museum of Natural History, Athens, GA "M. Hodge, Louisiana School of Math, Science, and the Arts, Natchitoches, LA "T.L. Schiefer, Mississippi Entomological Museum, Starkville, MS: S. Peyton, Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, Jackson, MS; M.B. Layton, Mississippi State University, MS '"M.W. LaSalle, Pascagoula River Audubon Center, Moss Point, MS • • '-.x 'it •i.hl-r.-. •''':.. r;.- •" r..,,.i: • V 566 -- Vol. 11, No. 4 Southeastern Naturalist Appendix 2. Key to non-literature references used in Appendix 1. Abbrev. Full name of reference Location AMNH AUEM BG BY CAS CMNH CUAC DG F FI FMNH FSCA GB JAX KM American Museum of Natural History Auburn University Entomology Museum BugGuide.net Backyardnature.net California Academy of Sciences Carnegie Museum of Natural History Clemson University Arthropod Collection Dave's Garden Flickr Forestry Images Field Museum of Natural History Florida State Collection of Arthropods Giff Beaton's webpage Jacksonville Shell Club Kirk M. Rogers' webpages LSAM MCZ MEM NASDB' Louisiana State Arthropod Museum Museum of Comparative Zoology Mississippi Entomological Museum Nearctic Spider database OBS NCSP O.B. Sirius blog North Carolina State Parks NRID system P SP SR TAMUIC UGCA USNM W WTB YPM Picasa StockphotoPro Spiderzrule Texas A&M University Insect Collection University of Georgia Collection of Arthropods National Museum of Natural History Webshots What's that bug? Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History New York, NY Auburn, AL http://bugguide.net http://backyardnature.net .;-i' ; San Francisco, CA ^ ^ ;. Pittsburgh, PA "'•, ;.., ., Clemson, SC http://davesgarden.com http://www.flickr.com ''"' http://www.forestryimages.org '' Chicago, IL Gainesville, FL http://www.giffbeaton.com http://www.jaxshells.org http://www.kiroastro.com/writings/ georgiaj3hotography.html Baton Rouge, LA Cambridge, MA Starkville, MS http://www.canadianarachnology. org/data/canada_spiders http://obsirius.blogspot.com http://www.dpr.ncparks.gov/nrid/ gallery.php <> https://picasaweb.google.com http://www.stockphotopro.com http://spiderzrule.com College Station, TX ^'" Athens, G A ' 'Jf' Washington, DC http://www.webshots.com • http://whatsthatbug.com New Haven, CT 'NASBD has been offline since 17 March 2010. This dataset can be accessed through the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (http://www.gbif.org/) ) • Copyright of Southeastern Naturalist is the property of Humboldt Field Research Institute and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.