Uploaded by

529401982

Marginal Structural Models for Physical Activity & Blood Pressure

advertisement

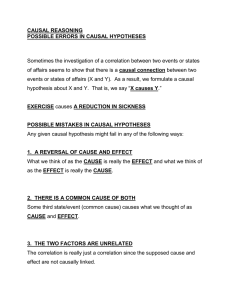

Article A graphical perspective of marginal structural models: An application for the estimation of the effect of physical activity on blood pressure Statistical Methods in Medical Research 0(0) 1–9 ! The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0962280216680834 smm.sagepub.com Denis Talbot,1,2,3 Amanda M Rossi,4,5,6 Simon L Bacon,4,5 Juli Atherton1 and Geneviève Lefebvre1 Abstract Estimating causal effects requires important prior subject-matter knowledge and, sometimes, sophisticated statistical tools. The latter is especially true when targeting the causal effect of a time-varying exposure in a longitudinal study. Marginal structural models are a relatively new class of causal models that effectively deal with the estimation of the effects of time-varying exposures. Marginal structural models have traditionally been embedded in the counterfactual framework to causal inference. In this paper, we use the causal graph framework to enhance the implementation of marginal structural models. We illustrate our approach using data from a prospective cohort study, the Honolulu Heart Program. These data consist of 8006 men at baseline. To illustrate our approach, we focused on the estimation of the causal effect of physical activity on blood pressure, which were measured at three time points. First, a causal graph is built to encompass prior knowledge. This graph is then validated and improved utilizing structural equation models. We estimated the aforementioned causal effect using marginal structural models for repeated measures and guided the implementation of the models with the causal graph. By employing the causal graph framework, we also show the validity of fitting conditional marginal structural models for repeated measures in the context implied by our data. Keywords marginal structural models, causal diagrams, time-dependent confounding, times-varying exposure, variable selection 1 Introduction Estimating the causal effect of a time-varying exposure with covariate-adjusted regression models can lead to biased estimates if a time-varying confounding covariate is an effect of previous exposure.1,2 For instance, Hernán et al. explain why adjusting for such time-dependent confounders by including them as additional regressors in a generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression can yield inappropriate inferences.2 The most common implementation of marginal structural models (MSMs) omits covariates in the outcome model and effectively deals with time-dependent confounding using inverse probability weighting.2–4 When implementing MSMs in such a way, a weight is computed for each individual and consists of the product over the inverse propensities at each time point of receiving the observed treatment given prior covariates and treatments. An MSM eliminates confounding if the sequential randomization assumption is satisfied, but identifying an appropriate set of covariates for calculating the weights is challenging in practice.5 1 Département de Mathématiques, Université du Québec à Montréal, Québec, Canada Département de Médecine Sociale et préventive, Université Laval, Québec, Canada 3 Unité Santé des Populations et Pratiques Optimales en Santé, Centre de recherche du CHU de Québec – Université Laval, Québec, Canada 4 Department of Exercise Science, Concordia University, Québec, Canada 5 Montreal Behavioural Medicine Centre, CIUSS-NIM, Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal, Québec, Canada 6 Division of Clinical Epidemiology, Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, Québec, Canada 2 Corresponding author: Denis Talbot, Département de médecine Sociale et préventive, Université Laval, Québec, Canada. Email: denis.talbot@fmed.ulaval.ca 2 Statistical Methods in Medical Research 0(0) MSMs have traditionally been embedded in Rubin’s counterfactual framework to causal inference,6 even though causal graphs have previously been used to illustrate the relationships between variables in MSMs analyses.1,7 In this paper, we propose to further embed MSMs in the graphical framework to enhance the implementation of these models.8 This graphical framework entails using graphs to represent the relationships between variables of primary interest and their potential confounders and is notably becoming one of the most popular tools to perform causal inference in epidemiology and other medical sciences. One of the main reasons this graphical framework has become so popular is because it provides simple rules for selecting adjustment variables to eliminate or reduce confounding bias that can be verified by inspecting the graph. We therefore expect our proposed methodology to aid in the practical implementation of MSMs. We illustrate our approach by estimating the causal effect of physical activity on blood pressure (BP) using data from the Honolulu Heart Program (HHP). The first step of our methodology is to build, based on substantive prior knowledge, an initial graph to represent the relationships between the variables of primary interest and the potentially confounding covariates. This graph is then validated and improved using the data. Lastly, the implementation of the MSMs is directly guided by the final improved graph. We are unaware of any previous work wherein the implementation of MSMs was based on a graph tested against the observed data. The primary aim of this paper is two-fold: (1) illustrate the statistical methodology we used to estimate the effect of physical activity on BP; (2) compare the results obtained using our graphical approach with those obtained using a naive approach for selecting the variables utilized in the weights’ models. A secondary aim is to show the validity of fitting conditional marginal structural models for repeated measures (MSMRMs) in the context implied by our data. 2 Data The HHP is a prospective cohort study that followed 8006 Japanese-American men living on the island of Oahu, Hawaii from 1965 until 1994. The participants were initially recruited between 1965 and 1968 from a listing of selective service registrants. The data collection protocol has been described elsewhere.9 Our analyses were based on three examinations for which comparable measures of physical activity, and both systolic BP and diastolic BP (SBP and DBP, respectively) were taken: Visit 1 (1965–1968), Visit 2 (1968–1971) and Visit 3 (1991–1993). The main variables of interest were self-reported physical activity (1 ¼ moderate activity or more, 0 ¼ less than moderate activity), SBP (in mmHg) and DBP (in mmHg). For our illustration, we also considered the HHP variables that were identified as clinically relevant or as potential confounders, and that were measured in a similar manner at all three visits. Those variables, which are all time-varying, were: age (in years), employment status (currently employed or not), body mass index (BMI, in kg/m2), smoking status (current smoker, previous smoker or never smoker) and anti-hypertension medication usage (yes or no). 3 Building the causal graph The issue of confounding is particularly challenging in the context of longitudinal data, such as the HHP, where intermediate covariates in the pathway between the exposure and the outcome can also act as confounding covariates. Using substantive prior knowledge, we began by drawing a directed acyclic graph (DAG) to represent the causal relationships between the selected variables at all visits.10 The main objective in building the DAG was to identify sets of variables that could be used to eliminate confounding. The inclusion or exclusion of arrows between variables and their directionality was carefully decided based on prior knowledge in the scientific literature. For example, previous research supports that a low socioeconomic status increases the risk of smoking.11 We have thus drawn an arrow from Employment, as a proxy of socioeconomic status, to Smoking. Moreover, previous research has shown that socioeconomic status and physical activity influence BMI,12 hence we have drawn arrows from Employment and Physical activity to BMI. 3.1 Assessing the fit of and improving the initial DAG We verified whether or not our proposed DAG fit the data well using structural equation models (SEMs). SEMs are statistical models that combine qualitative cause–effect assumptions with data to test causal models and estimate causal relationships. Most current SEM packages assume linear relationships between variables and multivariate normality of the data. We used the Lavaan package in R to fit the SEMs.13,14 The multivariate Talbot et al. 3 normality assumption is untenable in our case, since many of our variables are not continuous (e.g., Smoking and Employment), hence we assessed the goodness-of-fit of our proposed causal models with Bollen-Stine bootstrap,15 a statistical test that is robust to non-normality of data. We note, however, that we were partially restrained in our ability to test the proposed DAG. For instance, only subjects without any missing data at any visits can be included in the SEMs when using the Bollen-Stine bootstrap in Lavaan v0.5-20. Despite these limitations, we believed that any input we could get from the data to assess the correctness of our initial DAG was valuable. Descriptive statistics showed that the correlation between SBP and DBP was large at Visits 1 and 2 (r ¼ 0.77) and relatively large at Visit 3 (r ¼ 0.54). Because of this, and since we intended to investigate the effect of physical activity on SBP and DBP separately, we decided to fit separate SEMs for SBP and DBP, hence avoiding the possible complications associated with fitting a model containing highly correlated variables.16 Also, because the number of available subjects is largest at Visit 1 and smallest at Visit 3, we took full advantage of the available information by sequentially fitting larger and larger models. We began by fitting SEMs that only involved the relationships between the variables at Visit 1, then we fit SEMs for Visits 1 and 2, and lastly, SEMs for Visits 1, 2 and 3. Thus, we tested a total of six SEMs (1: SBP Visit 1; 2: DBP Visit 1; 3: SBP Visits 1 and 2; 4: DBP Visits 1 and 2; 5: SBP Visits 1, 2 and 3; 6: DBP Visits 1, 2 and 3). The initial DAG we had proposed did not fit the data well according to the chi-square statistics from the six SEMs. This chi-square statistic tests whether the observed data could be compatible with the proposed DAG by comparing the observed covariance matrix of the variables in the SEM with the covariance matrix that is generated by the SEM. Because the fits of the SEMs were poor, we included additional causal links (cause–effect paths and unobserved common causes) between the variables. We used modification indices as pointers toward sections of the DAG, where the fit was particularly poor. A modification index represents the expected improvement in the chi-square statistic that would occur if a causal link were added to an SEM. For example, our initial DAG did not include any direct connections between variables at Visit 1 and variables at Visit 3, because we believed that the delay between these two time points was long enough to preclude any direct effect. However, modification indices suggested our initial intuition was wrong and we decided to include such direct connections. Of note, the decision to include or not an additional link and which link to add in order to improve the fit was based on substantive knowledge. In other words, although we used the data to pinpoint lacks of fit in the DAG, the modifications were not made in a purely data-driven fashion. For instance, one prior hypothesis was that the DAG should have the same core structure at all visits. That is, we believed that there was no reason for the variables that were connected together, or for the directionality of the connections, to vary from one visit to another. Similarly, we saw no reason for the connections between the same variables in the SEMs for SBP and DBP to differ; as such, it was decided that the SEMs should have exactly the same structure. All final SEMs, except the one for SBP at Visits 1, 2 and 3, had non-significant chi-square statistics (p > 0.05). Despite the modifications we made, the final SEM for SBP at Visits 1, 2 and 3 still had a slightly significant chisquare statistics (p ¼ 0.044). We could find no further modifications to the SEMs that made sense from a theoretical point of view. We therefore investigated if some observations were highly influential in the calculation of the chi-square statistic. To do so, we repeatedly fitted the SEM for SBP at Visits 1, 2 and 3, removing one observation at a time. We found two observations that were particularly influential in the chisquare statistic calculation. Fitting the model without these observations yielded a non-significant chi-square statistic (p ¼ 0.061). One of these observations had a relatively extreme value for SBP at Visit 3 (221 mmHg) in addition to having a somewhat unusual combination of the values of the variables (e.g. very high BP at all three visits, but never taking anti-hypertensive medication). We could not find anything peculiar about the other observation by simply inspecting its values. In the end, our SEMs appeared to be a reasonable representation of the causal process between the selected variables. Using the six final SEMs, we updated our initial DAG. Figure 1 presents a part of the final DAG, showing nodes at Visit 1 only. The nodes for SBP and DBP have been joined into a single BP node in Figure 1 to simplify the presentation. The structural equations encoded in the complete final DAG are detailed in online Appendix A. 3.2 Identifying confounding variables If a time-varying confounding variable is on the causal pathway between the exposure and the outcome, direct adjustment for this confounding variable in an outcome model can lead to biased estimates.1 The complete final DAG obtained in the previous section confirmed that we were in the presence of such time-varying confounding variables. For instance, BMI at Visit 1 confounds the relationship between Physical activity at Visit 2 and BP at 4 Statistical Methods in Medical Research 0(0) Physical activity Hypertens. med. Age Employment Blood pressure Smoking BMI Figure 1. A close-up of the final DAG at Visit 1. Solid arrows represent putative cause-to-effect relationships. Double-headed dashed arrows between two variables are a notational shortcut to represent hypothesized common causes between these variables. Visit 2 (Physical activity at Visit 2 BMI at Visit 1 !BP at Visit 2), and BMI at Visit 1 is also an effect of Physical activity at Visit 1 (Physical activity at Visit 1 ! BMI at Visit 1). On the basis of a causal DAG, Pearl’s back-door criterion provides sufficient conditions to identify sets of variables that eliminate confounding when estimating the causal effect of an exposure variable on an outcome variable.8 In the next two sections, we present the MSMs we used to estimate the causal effects of interest. As subsequently detailed, Pearl’s back-door criterion was invoked to identify sets of covariates sufficient to satisfy the sequential randomization assumption underlying the MSM analyses. 4 Marginal structural models for repeated measures In this section, we describe the MSMRMs used to estimate the causal effects of physical activity on current SBP and DBP. In the sequel, we generically explain the modeling process in terms of BP, since it is the same for both SBP and DBP. To simplify the presentation, we proceed for now as if all subjects were observed at every visit. We first introduce some notations for MSMs. Our notation is very similar to that in Hernán et al.,2 but eliminates the reference to counterfactual outcomes to accommodate the causal graphical framework we consider. Let i ¼ 1, . . . , n denote the individuals, Y(t) be the random variable representing the BP value at Visit t ¼ 1, 2, 3, and X(t) be the random variable representing the Physical activity level at Visit t (X(t) ¼ 1 denotes moderate activity or more, whereas X(t) ¼ 0 denotes less than moderate activity). We modeled the effect of current and prior physical activity history on current BP as a function of current physical activity (recall the long delay between Visit 2 and Visit 3). We thus considered the following model E½YðtÞ ¼ 0 þ 1 XðtÞ þ 2 t ð1Þ where 0 is the unknown intercept, 1 is the unknown parameter associated with the physical activity level and 2 is the unknown slope parameter associated with the visit. It is common in MSMRMs to introduce a parameter associated with t, the visit number (for instance, see Hernán et al.2). In equation (1), this parameter allows the intercept of BP to vary with visits. Ignoring the complications arising from missing data and possible informative censoring, the parameters of model (1) can be directly estimated by fitting a GEE regression to an augmented dataset, where each row corresponds to a given subject at a given visit. However, for 1 to have a causal interpretation, time-dependent confounding must be adequately dealt with. This is done by attributing an inverse probability of treatment weight (IPTW) to each subject-visit. Talbot et al. 5 As will be subsequently seen in equation (3), sets of variables LXY ðtÞ, t ¼ 1, 2, 3, were used to calculate the subject-specific IPTWs. Let yi ðtÞ, xi ðtÞ and liXY ðtÞ be the observed realizations of Y(t), X(t) and LXY ðtÞ for subject i, respectively. In the counterfactual framework, the variables LXY entering the weights’ models are chosen so that the sequential (conditional) randomization assumption holds.2 Because model (1) only depends on the most recent exposure, this assumption can be simplified to Yx ðtÞ??XðtÞjLXY ðtÞ, t 2 f1, 2, 3g 8x, ð2Þ where Yx ðtÞ is the counterfactual BP value at Visit t that would have been observed if, possibly contrary to the fact, the physical activity history x had been observed. Considering Theorem 4.4.1 from Pearl, Section 4.4.3,8 we find that the effect of X(t) on Y(t) can be identified conditional on LXY ðtÞ if LXY ðtÞ is a set of non-descendants of X(t) that blocks every back-door path from X(t) to Y(t). Hence, on the basis of the complete final DAG mentioned in Section 3, the variables we selected in LXY ðtÞ satisfied the back-door criterion. A complete list of the variables in LXY is available in online Appendix B. We considered the weighted GEE regression model (1) with stabilized weights WXY i ðtÞ ¼ Y PðXðkÞ ¼ xi ðkÞÞ PðXðkÞ ¼ xi ðkÞjLXY ðkÞ ¼ liXY ðkÞÞ kt,k2f1,2,3g ð3Þ and estimated PðXðkÞ ¼ xi ðkÞÞ and PðXðkÞ ¼ xi ðkÞjLXY ðkÞ ¼ liXY ðkÞÞ using logistic regression.17 Before turning to the estimation with incomplete data, we discuss how confounding covariates could have been selected using a DAG if the outcome had depended on the complete exposure history in the postulated outcome model, instead of depending only on the most recent exposure as in model (1). In such a case, the following sequential randomization assumption would need to be met for each k t 1Þ, LXY ðk, tÞg, fYx ðtÞ??XðkÞjXðk t 2 f1, 2, 3g 8x, ð4Þ 1Þ represents the physical activity history up to, and including, Visit k 1 (Xð0Þ where Xðk is defined as the XY empty set, ). The effect of XðtÞ on Y(t) is identified if the sets L ðk, tÞ meet the sequential back-door criterion.8 More precisely, (1) LXY ðk, tÞ must consist of non-descendants of fXðkÞ, . . . , XðtÞg and (2) all paths between X(k) and 1Þg in the modified DAG obtained by removing from the original DAG Y(t) must be blocked by fLXY ðk, tÞ, Xðk all arrows pointing into X(k) and all arrows emerging from nodes fXðk þ 1Þ, . . . , XðtÞg. 4.1 Estimation with incomplete data Up until now, we have presented the MSMRMs we would have fit to estimate the effect of physical activity on BP had there been no deaths or losses to follow-up. Recall that the HHP is a longitudinal study that spanned over a very long period of time (from 1965 until 1993). Inevitably, many subjects died before the end of the study (n ¼ 3,676) or were lost to follow-up (n ¼ 485). Therefore, we did not have a complete dataset where every subject participated at every visit. Because a weighting scheme is already used to account for confounding, it was convenient to employ inverse probability of censoring weights (IPCWs) to deal with incomplete follow-up in our MSMRMs.2,18 Let C(t) be a random variable representing the censoring at Visit t, with Cð0Þ 0, and let ci ðtÞ be the observed realization for subject i (ci ðtÞ ¼ 0 if subject i is still in the study at Visit t and ci ðtÞ ¼ 1 otherwise). Also, let ZðtÞ denote all the covariates available at Visit t and zi ðtÞ be their observed values for subject i. Our weights for censoring are Y PðCðkÞ ¼ 0jCðk 1Þ ¼ 0Þ WC i ðtÞ ¼ PðCðkÞ ¼ 0jCðk 1Þ ¼ 0, ZðkÞ ¼ zi ðkÞÞ kt,k2f1,2,3g We estimated PðCðkÞ ¼ 0jCðk 1Þ ¼ 0Þ and PðCðkÞ ¼ 0jCðk 1Þ ¼ 0, ZðkÞ ¼ zi ðkÞÞ using logistic regression. XY For i ¼ 1, . . . , n, we computed the total weights as WTotal ðtÞ ¼ WC i i ðtÞ Wi ðtÞ, and then calculated the Total corresponding normalized weights NWi ðtÞ as described in equation (4) in Xiao et al. (2014).4 Finally, the GEE regression (1) was fit with weights NWTotal ðtÞ. It has been shown that bias might be introduced when i 6 Statistical Methods in Medical Research 0(0) using a non-independent working correlation in conjunction with occasion-specific weights, such as ours.19,20 We therefore used an independent working correlation matrix and a robust variance estimator to account for the repeated measures in the GEE regression. 4.2 Conditional marginal structural models for repeated measures It is usually recommended not to include time-varying variables in the outcome model (1) of an MSMRM.2 This is because some of these variables can act both as confounders and intermediate variables over time.1 In this section, we present a conditional MSMRM and argue that its specification is valid. More precisely, we suggest that it is correct to include time-varying variables UðtÞ in the model we consider, even if UðtÞ includes such time-dependent confounders. We considered the following conditional model to estimate the causal effect of physical activity on BP E½YðtÞjUðtÞ ¼ 0 þ 1 XðtÞ þ 2 t þ b3 UðtÞ ð5Þ where b3 is a vector of unknown parameters. With the back-door criterion in mind, the variables UðtÞ we selected were such that they were not descendants of X(t) according to our complete final DAG, and that all back-door paths between X(t) and Y(t) remained blocked after conditioning on U(t). These variables are Age, Employment and Smoking at Visit t. Note that UðtÞ may have included variables on the causal pathway between X(s) and Y(t), s < t, without introducing bias in the estimation of 1. This is because model (5) only considers the effect of X(t) on Y(t). We estimated the corresponding causal effect of physical activity on BP as presented in Section 4.1. That is, we built an augmented dataset and fit the weighted GEE regression model (5) using the same normalized weights as before. In online Appendix C, we present a simulation study that validates our methodology. The results of this simulation are briefly discussed in Section 5.2. 5 Analyses and results 5.1 Contrasting our approach with a naive approach In this paper, we have proposed a graphical approach to MSMs where the covariates selected for estimating the IPTWs are identified using a DAG and the back-door criterion. A more naive approach for estimating the IPTWs is to use every potentially confounding covariates available at a given visit. The first line of Table 1 presents the results obtained by estimating the causal effects of physical activity on SBP and DBP using the unconditional MSMRM described in Section 4, equation (5). For the naive approach, the causal effects were estimated similarly, only replacing LXY ðtÞ by LXY N ðtÞ in the IPTWs (3). The variables in LXY N ðtÞ, t ¼ 1, 2, 3, are listed in online Appendix B. The results obtained using the naive approach are presented in the second line of Table 1. The estimated causal effects of physical activity on SBP obtained with the naive and the graphical approaches are both compatible with a decrease in SBP when physically active. However, the interpretation of the results for DBP differs. Indeed, the results obtained using the graphical approach are compatible with no effect of physical activity on DBP, whereas the results pertaining to the naive approach suggest that being physically active increases DBP. That physical activity would increase DBP is not supported by the current scientific knowledge.21 The observed divergence in conclusions lends support to our proposed approach. Table 1. Results from the graphical and naive approaches to estimate the causal effects of current physical activity on SBP and DBP in mmHg (95% confidence intervals in parentheses). Approach SBP DBP Graphical Naive 2.01 (2.98, 1.04), p < 0.01 1.19 (2.17, 0.22), p ¼ 0.02 0.27 (0.22, 0.75), p ¼ 0.28 0.93 (0.44, 1.41), p < 0.01 DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure. Talbot et al. 7 Table 2. Results from using unconditional and conditional MSMRMs to estimate the causal effects of physical activity on SBP and DBP (95% confidence intervals in parentheses). Parameter Unconditional SBP Conditional SBP Physical activity Age Employed Current smoker Previous smoker Physical activity Age Employed Current smoker Previous smoker –2.01 (–2.98, –1.04), p < 0.01 NA NA NA NA 0.27 (0.22, 0.75), p ¼ 0.28 NA NA NA NA –1.48 (–2.42, –0.55), p < 0.01 0.55 (0.47, 0.63), p < 0.01 –8.25 (–9.34, –7.15), p < 0.01 –0.65 (–1.66, 0.35), p ¼ 0.20 1.17 (0.13, 2.20), p ¼ 0.03 0.20 (0.29, 0.68), p ¼ 0.43 –0.05 (–0.09, 0.00), p ¼ 0.03 1.71 (1.23, 2.18), p < 0.01 –1.80 (–2.35, –1.26), p < 0.01 –0.24 (0.80, 0.31), p ¼ 0.39 DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure. Note: Only the parameter associated with physical activity has a causal interpretation. 5.2 Comparing conditional and unconditional MSMRMs The results of the simulation study that investigated the performance of conditional MSMRMs suggest that such a type of MSMRMs yields unbiased and more precise estimates in some situations (see online Appendix C). Moreover, the conditional MSMRM produced less biased estimators of the causal effect than unconditional MSMRM when the weights’ models were incorrectly specified. We then compared the estimates obtained using the unconditional MSMRM (1) and the conditional MSMRM (5) for the HHP data. The conditional MSMRM adjusts for the time-varying covariates UðtÞ ¼ fAge, Employment and Smoking at Visit tg. The results obtained from these conditional and unconditional MSMRMs are in agreement (see Table 2). No clear benefit was seen with the use of a conditional MSMRM for this application. 6 Discussion Using the HHP to illustrate our approach, we have devised and implemented MSMs in the graphical framework to causal inference. This graphical framework can be particularly helpful when selecting variables used to construct the IPTWs, which are central to fitting MSMs to data. Using substantive prior knowledge, our approach first consisted of drawing a DAG to represent the links between the selected clinically relevant and potentially confounding variables. Structural equation models were then used to assess the correctness of the postulated DAG and to improve this DAG. The last step was to identify the confounding variables upon the examination of the final DAG and by invoking Pearl’s back-door criterion. Selecting variables to calculate IPTWs has previously been recognized as a challenge in the implementation of MSMs.5 This was further illustrated in our paper, where a naive approach to variable selection was shown to yield implausible results. Contra to this, the graphical approach we developed for the analysis of the HHP data gave results more consistent with the current scientific knowledge. We note that it is common in the SEM field to use approximate fit indices, such as the root-mean-square of error approximation (RMSEA) or the comparative fit index (CFI), in addition to, or instead of, the chi-square test to measure the fit of a SEM to the data. In fact, it is sometimes argued that the chi-square test of fit for SEMs is nearly always significant when the sample size is large enough because it has the ability to detect very small inconsistencies between the observed covariance matrix and the model-generated covariance matrix. Fit indices whose values are independent of sample size have therefore been introduced as a solution to this apparent problem. However, it has been remarked that even small differences between the observed and the modelgenerated covariance matrices might be a sign of serious causal misspecifications of the model.22,23 Therefore, although it would have been possible to assess the fit of our SEMs utilizing approximate fit indices, we believe that the chi-square test was more appropriate in our causal inference context. A word of caution regarding our methodology is also in order. By using the data for modifying the initial DAG, there is a risk of overfitting. That is, there is a risk that connections between some variables would be observed in the data due to chance alone and would not represent a true association in the population. A DAG that would be altered by blindly following the changes suggested by modification indices might turn out to include too many or 8 Statistical Methods in Medical Research 0(0) incorrect pathways. We believe that this risk has been mitigated by using modification indices in conjunction with substantive knowledge in order to make the best final decision regarding how to improve the fit of our DAG. We also proposed a conditional version of the MSMRMs to estimate the causal effects of physical activity on SBP and DBP. Although no clear advantages were seen for the HHP data, the use of conditional MSMRMs ought not to be neglected in practice. Indeed, the simulation we performed resulted in unbiased conditional estimators with smaller standard errors than the unconditional ones. We also observed that conditional MSMRMs offer some protection to the bias that would otherwise result from a misspecification of the weights’ models. It is important to keep in mind that our conditional MSMRMs were fit in a very specific context in which the physical activity history was summarized using only the most recent level of physical activity. Our approach could, however, be easily generalized to other situations, for instance where physical activity history is summarized using the two most recent levels of physical activity. Following a reasoning similar to the one presented in Section 4.2, one would select the variables used for conditioning in the structural model utilizing the back-door criterion to ensure that the conditioning does not introduce bias in the estimation of the causal parameters. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Talbot has been supported by doctoral scholarships from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Fonds de recherche du Québec: Nature et Technologies. Rossi is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, and Fonds de la recherche du Québec-Santé Bourse de formation Doctorat. Lefebvre is supported by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and is a Chercheur-Boursier of the Fonds de recherche Québec – Santé. Atherton is supported by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Bacon is supported by the Fonds de la recherche du Québec – Santé Chercheur-Boursier and received personal fees from Kataka Medical Communication during the conduct of the study outside the submitted work; and is Chair of the Canadian Hypertension Education Programme’s Recommendations Task Force Health Behaviours Sub-committee, which deals with generating recommendations about the role of health behaviours in the prevention and treatment of hypertension. The Honolulu Heart Program was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). References 1. Robins JM, Hernán MA and Brumback BA. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 2000; 11: 550–560. 2. Hernán MA, Brumback BA and Robins JM. Estimating the causal effect of zidovudine on CD4 count with marginal structural model for repeated measures. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1689–1709. 3. Robins JM. Marginal structural models. Proceedings of the Section on Bayesian statistical science. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association, 1997, pp.1–10. 4. Xiao Y, Abrahamowicz M and Moodie EEM. Accuracy of conventional and marginal structural Cox model estimators: a simulation study. Int J Biostat 2010; 6: 1–28. 5. Cole SR and Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168: 656–664. 6. Rubin D. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J Educ Psychol 1974; 66: 688–701. 7. VanderWeele TJ, Hawkley LC and Carioppo JT. On the reciprocal association between loneliness and subjective wellbeing. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 176: 777–784. 8. Pearl J. Causality: models, reasoning, and inference, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009. 9. Kagan A, Harris BR, Winkelstein W Jr, et al. Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California: demographic, physical, dietary and biochemical characteristics. J Chronic Dis 1974; 27: 345–364. 10. Hernán MA, Hernández-Dı́az S, Werler MM, et al. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155: 176–184. 11. Gilman SE, Abrams DB and Buka SL. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: initiation, regular use, and cessation. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003; 57: 802–808. Talbot et al. 9 12. Sundquist J and Johansson SE. The influence of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and lifestyle on body mass index in a longitudinal study. Int J Epidemiol 1998; 27: 57–63. 13. R Core team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013. 14. Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 2012; 48: 1–36. 15. Bollen KA and Stine RA. Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res 1992; 21: 205–229. 16. Grewal R, Cote JA and Baumgartner H. Multicollinearity and measurement error in structural equation models: implications for theory testing. Market Sci 2004; 23: 519–529. 17. Talbot D, Atherton J, Rossi AM, et al. A cautionary note on the use of stabilized weights in marginal structural models. Stat Med 2015; 34: 812–823. 18. Moodie EEM, Delaney JAC, Lefebvre G, et al. Missing confounding data in marginal structural models: a comparison of inverse probability weighting and multiple imputation. Int J Biostat 2008; 4: 1–23. 19. Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, Weuve J, et al. A cautionary note on the specification of the correlation structure in inverse-probability-weighted estimation for repeated measures. Harvard University Biostatistics Working Paper Series 2012; Working Paper 140. 20. Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, Weuve J, et al. Specifying the correlation structure in inverse-probability-weighting estimation for repeated measures. Epidemiology 2012; 23: 644–646. 21. Cornelissen VA and Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2: e004473. 22. Hayduk LA. Shame for disrespecting evidence: the personal consequences of insufficient respect for structural equation model testing. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 124. 23. Antonakis J, Bendahan S, Jacquart P, et al. On making causal claims: a review and recommendations. Leadersh Q 2010; 21: 1086–1120.