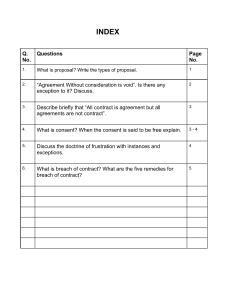

Law of Contract Nature of the law of Contract The law of contract may be defined as that branch of the law which determines the circumstances in which a promise will be legally binding on the person making the promise (the 'promisor') and enforceable in a court of law by the person to whom the promise was made (the 'promisee'). A well-accepted definition is that contained in section 1 of the American Law Institute's Second Restatement of the Law of Contracts: 'A contract is a promise or a set of promises for the breach of which the law gives a remedy, or the performance of which the law in some way recognizes as a duty.' The rationale for the enforceability of contracts is essentially the promotion of trade and commerce, which would be seriously hampered if contracting parties could not be held to their bargains. Accordingly, a party which enters into a valid contract can be assured that it will be able to recover compensation from the other party in the event of the latter's repudiation of the agreement or failure to perform its obligations, and the 'measure' (i.e. the amount) of damages recoverable in contract law is intended to compensate the innocent party not only for any material or financial damage sustained on account of the other party's breach, but also for any loss of profits or other benefits which it would have received if the contract had been performed by that other party. Enforceable contracts appear in a great variety of forms, ranging from, on the one hand, 'everyday' contracts entered into by consumers, such as those for the sale of goods in a supermarket, or for transportation of a passenger in a bus, train or plane, or for professional services to be rendered by a dentist, plumber or hairdresser to, on the other hand, complex commercial agreements such as large-scale building and civil engineering contracts affecting several corporate parties, any breach of which could inflict serious financial damage on one or more of the parties. In such a scenarios, each of the parties will depend on the others to carry out their contractual obligations and in the event of a breach by a promisor, the innocent promisee under the particular contract will have a right of action for breach of contract against the defaulting promisor. Freedom of contract The concept of 'freedom of contract' became a basic tenet of jurists, philosophers and economists in the nineteenth century, and it persisted in mainstream legal thinking until comparatively recently. At the heart of this principle is the notion that a party to a contract is expected to decide what is in his own best interests, and the law's function is simply to enforce agreements and not to interfere with them on grounds of 'unfairness' or 'unreasonableness'. This is the essence of laissez-faire economics. However, according to some contemporary jurists, the laissez-faire approach is acceptable only where the parties to a contract have 'equal bargaining power which would be the case where a contract is concluded between two corporate entities of equal economic 'muscle', but not where an individual consumer enters into a contract with, for instance, a utility company for the supply of electricity or telephone service, where the terms of the contract are standardized and not subject to bargaining, and where the consumer has no alternative but to accept those terms.1 Accordingly, limited protection for contracting parties having little or no bargaining power is afforded by statutory provisions in many jurisdictions,2 and the courts, in some instances, have refused to enforce contractual exemption clauses imposed by a stronger party on the weaker. Nevertheless, in 1967, Lord Reid, commenting on the effect of the so-called 'doctrine of fundamental breach', deprecated the idea of restricting 'the general principle of English Law that parties are free to contract as they may think fit', and in 1980, Lord Diplock reiterated the 'basic principle of the common law of contract ... that the parties are free to determine for themselves what primary obligations they will accept'.3 1 These are known as 'contracts of adhesion'. 2 Consumer Protection Act, 2006 (Jamaica). 3 Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd [1980] AC 827, at 843; Sanctity of contracts The principle of sanctity of contracts means that a contract, once made, must be observed and promises must be kept. The principle serves the requirements of the commercial community by giving security and certainty to contractual relations and providing assurance that transactions involving financial commitments on the part of the contracting parties will be enforced by the courts. The strictness of the principle is exemplified by the courts' refusal, before 1863, to allow a party to be freed of his contractual obligations on the ground of frustration. Before the case of Taylor v Caldwell,4 it was a strict rule that a party could not escape his obligations under a contract by pleading that a fundamental change in the circumstances since the date of the agreement had 'frustrated' the contract. Today, frustration is accepted as a ground for discharging a contract, but the circumstances in which the courts will allow the plea to succeed remain severely limited, and the current position is that frustration will discharge a contract only where the frustrating event 'strikes at the root of the contract', so that the agreement, after the event, becomes fundamentally different in character from that originally contemplated by the parties. Reference Kodilinye, G., & Kolilinye, M. (2014). Commonwealth Caribbean Tort Law (5th ed.). Third Avenue, o 4 New York: Routledge. (1863) 122 ER 309,