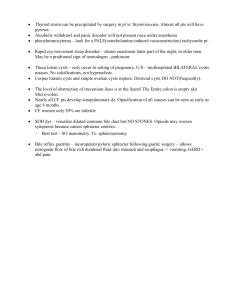

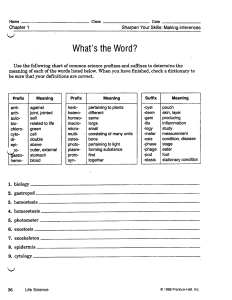

Original Article Cytologic Categorization of Pancreatic Neoplastic Mucinous Cysts With an Assessment of the Risk of Malignancy: A Retrospective Study Based on the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Guidelines Amber L. Smith MD; Fadi W. Abdul-Karim MD, MEd; and Abha Goyal MD BACKGROUND: Cytology plays a pivotal role in the preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. Here the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology (Pap Society) guidelines were used to reclassify and assess the malignancy risk of cytology diagnoses of histologically proven pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts. METHODS: A database search (January 2000 to June 2014) was performed for pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cyst resections with endoscopic ultrasound–guided fineneedle aspiration within the preceding year. Histologic diagnoses were reclassified according to the 2010 Word Health Organization criteria. For atypical/suspicious/positive cytology diagnoses, the cytology slides were reviewed, blinded to the histologic diagnoses. The cysts were reclassified according to the Pap Society guidelines, and the findings were correlated with the histology. RESULTS: One hundred thirty-eight cases of pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts were retrieved. Eleven cases with atypical/suspicious cytology diagnoses with unavailable slides were excluded. The remaining 127 cases included 81 intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and 46 mucinous cystic neoplasms. The sensitivity of cytology for the diagnosis of neoplastic mucinous cysts was 76.4%. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of cytology for the diagnosis of malignancy (high-grade dysplasia or worse) were 48.3%, 94.9%, and 84.3%, respectively. The risk of malignancy was 17.4% for the nondiagnostic category, 0% for the negative category, 13% for the neoplastic category, 63.6% for the atypical category, 80% for the suspicious category, and 100% for a positive diagnosis. CONCLUSIONS: This study reveals that the Pap Society guidelines allow the accurate categorization of pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts with cytology. The diagnostic categories (from negative to positive) are associated with an increasing risk of malignancy, C 2015 Ameriand this can further aid in patient management and risk stratification. Cancer Cytopathol 2016;124:285-93. V can Cancer Society. KEY WORDS: cyst; endoscopic ultrasound; fine-needle aspiration; mucinous; pancreas; Papanicolaou Society guidelines; risk of malignancy. INTRODUCTION With the widespread use of high-resolution abdominal imaging, the detection of pancreatic cysts, many of which are incidental, has considerably increased.1,2 A significant proportion of these cysts, up to 55% in 1 study, are composed of neoplastic mucinous cysts, that is, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs), which may require surgical intervention.3 Currently, endoscopic ultrasound guided–fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis and characterization of solid and cystic pancreatic masses.4–7 In terms of the evaluation of pancreatic cysts, the role of the cytopathologist is 2-fold: to establish whether the cyst is mucinous or nonmucinous and to determine Corresponding author: Abha Goyal, MD, Department of Pathology, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Avenue, L25, Cleveland, OH 44195; Fax: (216) 445-3707; abgoyal@yahoo.com Department of Pathology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio Received: August 25, 2015; Revised: October 27, 2015; Accepted: October 28, 2015 Published online November 30, 2015 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/cncy.21657, wileyonlinelibrary.com Cancer Cytopathology April 2016 285 Original Article whether there is any high-grade atypia or worse. Such a cytologic evaluation is critical in making clinical management decisions.8,9 The 2012 international consensus guidelines for the management of pancreatic mucinous neoplasms incorporate EUS-FNA into the management algorithm.10 Until recently, there was no standardized scheme for reporting pancreatic cytology. The Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology (Pap Society) has proposed a reporting terminology and classification for pancreatic cytology. This proposed scheme includes 6 categories: “nondiagnostic,” “negative for malignancy,” “atypical,” “neoplastic,” “suspicious for malignancy,” and “positive” or “malignant.” The neoplastic category has been further subdivided into “neoplastic: benign” and “neoplastic: other.” Aside from low-grade malignancies such as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and solid pseudopapillary neoplasms, the neoplastic: other category includes premalignant neoplastic mucinous cysts (ie, IPMNs and MCNs) with low-, intermediate-, or high-grade dysplasia. For neoplastic mucinous cysts without overt malignant features, a 2-tiered approach is recommended by the Pap Society for grading cellular atypia: low-grade atypia and high-grade atypia. Low-grade atypia usually correlates with low-grade dysplasia or intermediate-grade dysplasia on histologic follow-up, and high-grade atypia is usually associated with high-grade dysplasia or worse on histologic follow-up.11,12 This new classification aims to allow better communication between the pathologists and the clinicians to aid in the management and treatment of pancreatic lesions. However, there is limited information regarding the practical utility of these guidelines and the risk of malignancy associated with the different diagnostic categories. Our study was aimed at using the Pap Society guidelines to categorize pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts retrospectively and to stratify the risk of malignancy on the basis of such a categorization. MATERIALS AND METHODS This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Cleveland Clinic. A retrospective database search was performed from January 1, 2000 to June 30, 2014 for resections of pancreatic mucinous neoplasms (ie, IPMNs and MCNs). Only cases with EUS-FNA within the year preceding the resection were included. The cytologic and histologic diagnoses were recorded from the pathology reports. For cases with atypical, suspi286 cious, or positive cytology diagnoses, the fine-needle aspiration (FNA) slides were reviewed, blinded to the histologic diagnoses, and were categorized according to the Pap Society guidelines. The cytology slides from cases that had been initially categorized as negative or nondiagnostic were not reviewed. Histologic diagnoses were reclassified according to the 2010 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the digestive system as IPMN or MCN with low-/intermediate-/high-grade dysplasia or an associated invasive carcinoma.13 Patient demographic and clinical information and cyst fluid analysis data were obtained from the electronic medical record. The cysts were reclassified according to the Pap Society guidelines. Cysts with a carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level 192 ng/mL or with abundant extracellular, thick, colloid-type mucin or neoplastic mucinous epithelium were considered to be mucinous and were placed in the neoplastic: other category. Cysts with nonspecific cyst contents with an absence of extracellular mucin and neoplastic mucinous epithelium, low CEA levels (<192 ng/mL) and high amylase levels (>250 U/L) were considered negative. Cysts with acellular aspirates or nonspecific cyst contents with an absence of extracellular mucin/neoplastic mucinous epithelium, without any helpful ancillary studies (ie, amylase level < 250 U/L and CEA level < 192 ng/mL), or without available CEA levels were considered to be nondiagnostic. The cytology slides from cysts that were initially classified as atypical, suspicious, or positive were categorized as follows upon review. Those with diagnostic high-grade atypia were categorized as neoplastic: other with high-grade atypia. The cysts with low-grade atypia upon re-review were classified as neoplastic: other. Cysts with high-grade atypia and background coagulative necrosis with features insufficient for a positive-formalignancy diagnosis were classified as suspicious for malignancy. Cysts with sufficient cellularity to make an adenocarcinoma diagnosis were classified as positive for malignancy. On the basis of the aforementioned classification, the sensitivity of cytology for the diagnosis of neoplastic mucinous cysts was calculated. The sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value, positive predictive value, and accuracy of cytology for the diagnosis of malignancy (high-grade dysplasia or worse) were also calculated. The nondiagnostic cases were included in all these calculations. The absolute Cancer Cytopathology April 2016 Cytology of Pancreatic Mucinous Cysts/Smith et al risk of malignancy for each category was computed as follows: Absolute risk of malignancy 5 Number of malignant cases on histologic follow-up 4 Total number of cases RESULTS One hundred thirty-eight cases of pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts met the study criteria. Eleven cases with initial atypical/suspicious cytology diagnoses with slides unavailable for review were excluded from further analysis. Among the remaining 127 cases, there were 81 IPMNs and 46 MCNs. Among the 81 patients with IPMNs, there were 44 women and 37 men. The average age of the patients was 67 years (range, 44-87 years). Forty-one (50.6%) were located in the proximal pancreas (26 in the head, 13 in the uncinate, and 2 in the genu), and the remaining 40 (49.4%) were located in the distal pancreas (22 in the body and 18 in the tail). All but 1 of the 46 MCNs were diagnosed in women. The average age of the patients was 54 years (range, 29-79 years). Forty-three of the MCNs (93.5%) were located in the distal pancreas (19 in the body and 24 in the tail), and 3 (6.5%) were located in the proximal pancreas (2 in the head and 1 in the uncinate). Cytology and Cyst Fluid Biochemistry Seventy-eight cases (61.4%) had both ThinPrep preparations and direct smears available for cytologic assessment, 44 (34.6%) cases had ThinPrep preparations only, and the remaining 5 (3.9%) had smears only. Cytology was diagnostic of a neoplastic mucinous cyst in 74 cases (58.3%; Fig. 1A-D). CEA levels were available in 85 cases (66.9%). Fiftynine of these cases (69.4%) exhibited a CEA level 192 ng/mL (range, 194.9-176,600 ng/mL; median, 1743.2 ng/mL), which was considered diagnostic of a mucinous cyst. Of the 78 cases that were categorized as neoplastic: other, the CEA level was 192 ng/mL in 53 cases, < 192 ng/mL in 6 cases, and unavailable in the remaining 19 cases. Of the 19 cases with high-grade atypia or worse, CEA was 192 ng/mL in 6 cases, < 192 ng/mL in 2 cases, and unavailable in the remaining 11 cases. Ninety-seven cases (76.4%) had either diagnostic cytology or a CEA level diagnostic of a mucinous cyst. Cancer Cytopathology April 2016 CEA alone was diagnostic of a mucinous cyst in 23 cases (18.1%), and cytology alone was diagnostic in 38 cases (29.9%). According to the criteria outlined in the Materials and Methods section, 7 cysts (5.5%) were categorized as negative, and 23 cysts (18.1%) were considered to be nondiagnostic. Of the cases that were diagnosed as a mucinous cyst, 78 (61.4%) were categorized as neoplastic: other, 11 (8.7%) were categorized as neoplastic: other with highgrade atypia, 5 (3.9%) were categorized as suspicious for malignancy, and 3 (2.4%) were categorized as positive for malignancy (Fig. 2A-2D). The revised categorization of the study cases (based on cytology and CEA levels) is depicted in comparison with the original cytology categorization in Table 1. Histologic Correlation and Risk of Malignancy Of the 127 cases in our study, 29 (22.8%) were malignant on histologic follow-up: 25 IPMNs (15 with high-grade dysplasia and 10 with associated invasive carcinoma) and 4 MCNs (2 with high-grade dysplasia and 2 with associated invasive carcinoma). The remaining 98 cases (77.2%) were considered benign for the purposes of this study: 56 IPMNs (17 with intermediate-grade dysplasia and 39 with low-grade dysplasia) and 42 MCNs (4 with intermediategrade dysplasia and 38 with low-grade dysplasia). With the cytologic diagnosis of high-grade atypia or worse, 14 malignant cases (48.3%) were detected: 6 IPMNs with an associated invasive carcinoma, 7 IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia, and 1 MCN with high-grade dysplasia. With this diagnosis, cytology misclassified 5 benign neoplasms as malignant: 1 IPMN with low-grade dysplasia, 1 IPMN with intermediate-grade dysplasia, 2 MCNs with low-grade dysplasia, and 1 MCN with intermediate-grade dysplasia. With a positive cytology diagnosis, 3 malignancies (10.3%) were detected: all IPMNs with an associated invasive carcinoma. The diagnostic accuracy of cytology for malignancy was 84.3% with a diagnosis of high-grade atypia or worse and 75.6% with a positive diagnosis. The specificity of cytology for malignancy was 94.9% with a diagnosis of high-grade atypia or worse and 100% with a positive diagnosis. The absolute risk of malignancy for each cytologic category along with the histologic follow-up is shown in Table 2. 287 Original Article Figure 1. Cytologic features of a pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cyst with histologic correlation. (A) Thick, colloid-like mucin characteristic of a neoplastic mucinous cyst (Papanicolaou stain, 3 400). (B) On surgical resection, this was a main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with intestinal-type epithelium and intermediate-grade dysplasia (H & E stain, 3 200). (C) Mucinous epithelium with low-grade atypia against a background of thick mucin (Papanicolaou stain, 3 400). (D) On histologic follow-up, it was a branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with gastric foveolar-type epithelium with low-grade dysplasia (H & E, 3 200). DISCUSSION The diagnostic tools and management options for pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts have evolved over time. Imaging techniques, including computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), play an important role in the initial workup of these cysts.14,15 Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) offers a higher resolution than CT and MRI because of the close proximity of the transducer to the pancreas. As such, EUS is usually performed for a detailed evaluation of the cyst if the CT/MRI findings are indeterminate. In addition, EUS allows real-time sampling of the cyst through FNA.15–17 EUS with or without FNA is reportedly more accurate 288 than CT and MRI in predicting a cyst to be neoplastic and more accurate than CT in predicting malignancy in small cysts.18 EUS-FNA of pancreatic cysts yields material not only for cytologic assessment but also for biochemical and molecular analysis. The cytologic diagnosis for a neoplastic mucinous cyst depends on the presence of extracellular thick mucin and/or neoplastic mucinous epithelium with varying degrees of atypia. However, based on cytomorphology alone, the sensitivity of EUS-FNA for the diagnosis of neoplastic mucinous cyst ranges from 34.5% to 63%, and the accuracy is reportedly 59%.19,20 Cyst fluid biochemical analysis, including tumor marker CEA and Cancer Cytopathology April 2016 Cytology of Pancreatic Mucinous Cysts/Smith et al Figure 2. Cytologic features of pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts with high-grade atypia or worse with histologic correlation. (A) Atypical cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromasia, and irregular nuclear membranes characteristic of highgrade atypia. On surgical resection, this intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm exhibited high-grade dysplasia (Papanicolaou stain, 3 400). (B) High-grade atypia cells against a background of coagulative necrosis (features suspicious for adenocarcinoma). On histologic follow-up, there were foci of invasive adenocarcinoma associated with this intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (Papanicolaou stain, 3 200). (C) Adenocarcinoma of a tubular type arising in an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Note the thick mucin in the background (Papanicolaou stain, 3 400). (D) Surgical resection revealed an invasive adenocarcinoma in association with an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (H & E, 3 200). amylase levels, adds further information to cytologic analysis. The cooperative pancreatic cyst study reported that a cyst fluid CEA level 192 ng/mL exhibited an accuracy of 79% for classifying a cyst as mucinous.19 The cyst fluid amylase level in combination with CEA can also aid in the differentiation between mucinous and nonmucinous cysts. An amylase level < 250 U/L and a CEA level > 800 ng/ mL are unlikely to be associated with a pseudocyst.21 Molecular analysis can further add value to the information obtained by cytologic and biochemical analysis. In accordance with the Pancreatic Cyst Fluid DNA Analysis (PANDA) study, a combination of CEA and KRAS mutaCancer Cytopathology April 2016 tional testing increased the sensitivity of CEA alone from 67% to 84% for detecting a mucinous cyst.22 Sawhney et al23 reported a sensitivity and a specificity of 100% for the classification of a mucinous cyst when CEA and molecular analysis were combined. Also, the combination of GNAS and KRAS testing has been reported to be highly sensitive (84%) and specific (98%) for the diagnosis of IPMNs.24 As is apparent from the previous discussion, a purely cytologic approach is inferior to an integrated approach of cytology with ancillary testing in diagnosing a neoplastic mucinous cyst of the pancreas. Until recently, there had 289 Original Article TABLE 1. Revised Cytology Categorization in Comparison With the Original Diagnoses New Category Previous Category Diagnostic Basis Nondiagnostic (n 5 23) Negative (n 5 19) Nondiagnostic (n 5 4) Negative (n 5 7) Negative (n 5 7) Neoplastic: other (with low-grade atypia) (n 5 78) Negative (n 5 67) Atypical (n 5 9) Positive (n 5 1) Nondiagnostic (n 5 1) Atypical (n 5 8) Suspicious (n 5 3) Suspicious (n 5 3) Atypical (n 5 2) Positive (n 5 3) Cytology: nonspecific CEA: low or NA Amylase: low Cytology: nonspecific cyst contents CEA: low Amylase: high Cytology (n 5 25) CEA: high (n 5 23) Cytology and CEA (n 5 30) Neoplastic: other with high-grade atypia (n 5 11) Suspicious for malignancy (n 5 5) Positive for malignancy (n 5 3) Cytology Cytology Cytology Cytology Cytology Cytology (n 5 7) and high CEA (n 5 4) (n 5 4) and high CEA (n 5 1) (n 5 2) and high CEA (n 5 1) Abbreviation: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; NA, not available. TABLE 2. Cytologic Categories With Histologic Correlation and Risk of Malignancy Histologic Follow-Up, No. Cytologic Diagnostic Category Nondiagnostic (n 5 23) Negative (n 5 7) Neoplastic: other (with low-grade atypia) (n 5 78) Neoplastic with HG atypia (n 5 11) Suspicious for adenocarcinoma (n 5 5) Positive for adenocarcinoma (n 5 3) Total LG Dysplasia IG Dysplasia HG Dysplasia Adenocarcinoma 13 6 56 3 0 0 78 6 1 12 1 1 0 21 0 0 8 6 2 0 16 4 0 2 1 2 3 12 Absolute Risk of Malignancy, % 17 0 13 64 80 100 Abbreviations: IG, intermediate grade; HG, high-grade; LG, low-grade. been no standardized guidelines for the cytopathologist to report pancreaticobiliary cytology with an integrated approach. The Pap Society advocates a multidisciplinary approach for the diagnosis of pancreatic lesions and recommends the incorporation of all available relevant ancillary data to make a cytologic diagnosis.11,12,25 For the diagnosis of neoplastic mucinous cysts in our study, the sensitivity of cytology only was 58.3%, which is comparable to the results of other studies.20 For the cases with available CEA levels, a CEA level 192 ng/mL exhibited a sensitivity of 69.4%. Similarly to our results, Brugge et al19 and Sawhney et al23 showed that for the diagnosis of a mucinous cyst, a CEA value 192 ng/mL had a sensitivity of 73% and 82%, respectively. With the incorporation of the CEA levels, the diagnostic sensitivity of cytology rose to 76.4% in our study with an increment of 18.1%. However, it is important to note that cytology by itself was diagnostic in 38 cases (29.9%) for which CEA levels were low or unavailable. A recent meta-analysis 290 regarding the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA also revealed that a combined cytology and biomarker approach is essential for differentiation between mucinous and nonmucinous cysts.26 Our findings confirm that CEA levels are complementary to cytology in the diagnosis of a mucinous cyst and support the Pap Society recommendation of including the ancillary study results in cytology practice. After establishing that a cyst is mucinous, the other significant determination that needs to be made is whether the cyst is malignant (ie, it harbors high-grade dysplasia or an invasive carcinoma) or not. With the current sophisticated imaging techniques, the distinction between aggressive and nonaggressive cysts can be made with reasonable accuracy (reportedly 64%-86% for CT and 73%-91% for MRI).17,27–29 However, EUS-FNA with a cytologic assessment plays an important role in characterizing cysts that are not overtly malignant on imaging.15,16,18 Pitman et al8 have shown that on the basis of cytology, high-risk mucinous cysts can be most accurately recognized by the Cancer Cytopathology April 2016 Cytology of Pancreatic Mucinous Cysts/Smith et al identification of epithelial cells with high-grade atypia. The Pap Society recommends a 2-tiered approach for grading cytologic atypia in mucinous cysts when features suspicious or unequivocal for malignancy are not seen: low-grade atypia (inclusive of low- and intermediate-grade dysplasia) and high-grade atypia (inclusive of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma).11,12 In terms of molecular analyses for predicting malignancy in a mucinous cyst, there are currently insufficient data to warrant their usage in routine practice.25,30,31 The cytologic recognition of high-grade atypia or worse in our study resulted in an overall sensitivity of 48.3% and an accuracy of 84.3% for detecting malignancy in pancreatic mucinous cysts. In comparison, at the threshold of a positive cytology diagnosis, the sensitivity and accuracy for detecting malignancy were 10.3% and 75.6%, respectively. These results are similar to those reported in a study by Pitman et al8 in which high-grade atypical cells predicted malignancy in mucinous cysts with a sensitivity of 72% and an accuracy of 80%, and a positive cytology diagnosis had a sensitivity of 29% and an accuracy of 75%. The higher sensitivity for the detection of malignancy in mucinous cysts in their study may be in part due to the higher proportion of malignant cases (35.5%) in their study in contrast to ours (22.8%).8 As shown by these studies, the cytologic diagnosis of high-grade epithelial atypia has a higher sensitivity and accuracy for predicting malignancy in mucinous cysts than a positive cytology result. At the threshold of high-grade atypia, the specificity for the detection of malignancy in our study was 94.9%, which was less than the specificity of 100% attained with a positive diagnosis. This was due to 5 cases (including 3 mucinous neoplasms with low-grade dysplasia and 2 with intermediate-grade dysplasia) that were misclassified as high-grade atypia or worse on cytology. This cytologic pitfall of misinterpreting intermediate-grade dysplasia and occasional cases of low-grade dysplasia as high-grade atypia or worse has also been noted by other authors. Pitman et al8 reported that high-grade atypical epithelial cells were identified on cytology in 15% of benign cysts (6 with moderate dysplasia and 5 with low-grade dysplasia) in their study. In another study involving 70 EUS-FNAs of pancreatic cysts, the cytologic recognition of high-grade atypia resulted in 6 false-positive interpretations (4 of which were mucinous neoplasms with moderate dysplasia).32 An international observer concordance study also concluded that Cancer Cytopathology April 2016 intermediate-grade dysplasia is difficult to grade accurately with cytology.33 This shortcoming of cytologic analysis is also recognized by the Pap Society guidelines.11,12 Our findings confirm that the cytologic threshold of high-grade atypia is most accurate for predicting malignancy in mucinous cysts, but it may result in the resection of some cysts that are not high-grade. Another aim of our study was to determine the risk of malignancy associated with the different diagnostic categories for pancreatic cytology as proposed by the Pap Society. Our study demonstrates an increasing risk of malignancy associated with the different categories: 0% for a negative diagnosis, 13% for a neoplastic diagnosis, 63.6% for an atypical diagnosis, 80% for a suspicious diagnosis, and 100% for a positive diagnosis. The nondiagnostic category was associated with a 17.4% risk of malignancy. Our results were similar to those reported by Layfield et al.34 They reported the malignancy risk for the benign (negative), atypical, suspicious, malignant, neoplasm, and nondiagnostic categories of the Pap Society as 12.6%, 73.9%, 81.8%, 97.2%, 14.2%, and 21.4%, respectively. Our findings verify that the categorization proposed by the Pap Society provides valuable information regarding risk stratification for patient management. There were several limitations to our study. We did not include the cysts that were managed conservatively in our study to ensure the histologic confirmation of neoplastic mucinous cysts for all cases. Only cysts that had undergone resection were included, and this introduced a verification bias and likely led to an overestimation of the sensitivity of cytology for the diagnosis of a mucinous cyst and for the diagnosis of malignancy. Also, our study involved the retrospective application of Pap Society guidelines for the cytologic diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. It would be more helpful to apply these guidelines prospectively to assess their true role in clinical decision making. We do not usually incorporate molecular testing for the diagnosis of pancreatic cysts at our institution on a routine basis. Hence, we could not assess the role of molecular markers in determining whether a cyst was mucinous or malignant in our study. In conclusion, the Pap Society guidelines significantly refined our diagnostic approach to pancreatic mucinous cysts. They resulted in more meaningful cytologic diagnoses with well-defined criteria and the incorporation of 291 Original Article ancillary data. The categorization of the mucinous cysts into different categories on the basis of the presence or absence of diagnostic material and high-grade atypia or worse was associated with an increasing risk of malignancy, and this would have potentially proved instrumental in clinical management. Future prospective studies could further aid in defining the role of these guidelines in clinical decision making and risk stratification in the management of pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts. 13. 14. 15. 16. FUNDING SUPPORT No specific funding was disclosed. 17. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES The authors made no disclosures. 18. REFERENCES 1. Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, et al. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:802807. 2. Lee KS, Sekhar A, Rofsky NM, Pedrosa I. Prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts in the adult population on MR imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2079-2084. 3. Fernandez-del Castillo C, Targarona J, Thayer SP, Rattner DW, Brugge WR, Warshaw AL. Incidental pancreatic cysts: clinicopathologic characteristics and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Surg. 2003;138:427-423. 4. Frossard JL, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, et al. Performance of endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration and biopsy in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98: 1516-1524. 5. Moparty B, Logrono R, Nealon WH, et al. The role of endoscopic ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasound–guided fine-needle aspiration in distinguishing pancreatic cystic lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:18-25. 6. Yoshinaga S, Suzuki H, Oda I, Saito Y. Role of endoscopic ultrasound–guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) for diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses. Dig Endosc. 2011;23(suppl 1): 29-33. 7. Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Buxbaum JL, Eloubeidi MA. How good is endoscopic ultrasound–guided fine-needle aspiration in diagnosing the correct etiology for a solid pancreatic mass?: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Pancreas. 2013;42:20-26. 8. Pitman MB, Genevay M, Yaeger K, et al. High-grade atypical epithelial cells in pancreatic mucinous cysts are a more accurate predictor of malignancy than "positive" cytology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;118:434-440. 9. Genevay M, Mino-Kenudson M, Yaeger K, et al. Cytology adds value to imaging studies for risk assessment of malignancy in pancreatic mucinous cysts. Ann Surg. 2011;254:977-983. 10. Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183-197. 11. Pitman MB, Layfield LJ. Guidelines for pancreaticobiliary cytology from the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology: a review. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:399-411. 12. Pitman MB, Centeno BA, Ali SZ, et al. Standardized terminology and nomenclature for pancreatobiliary cytology: the Papanicolaou 292 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. Society of Cytopathology guidelines. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42: 338-350. Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Sahani DV, Kambadakone A, Macari M, Takahashi N, Chari S, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Diagnosis and management of cystic pancreatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:343354. Khalid A, Brugge W. ACG practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2339-2349. Nakai Y, Isayama H, Itoi T, et al. Role of endoscopic ultrasonography in pancreatic cystic neoplasms: where do we stand and where will we go? Dig Endosc. 2014;26:135-143. Sahani DV, Sainani NI, Blake MA, Crippa S, Mino-Kenudson M, del-Castillo CF. Prospective evaluation of reader performance on MDCT in characterization of cystic pancreatic lesions and prediction of cyst biologic aggressiveness. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 197:W53-W61. Khashab MA, Kim K, Lennon AM, et al. Should we do EUS/FNA on patients with pancreatic cysts?;. The incremental diagnostic yield of EUS over CT/MRI for prediction of cystic neoplasms. Pancreas. 2013;42:717-721. Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:13301336. Thosani N, Thosani S, Qiao W, Fleming JB, Bhutani MS, Guha S. Role of EUS-FNA-based cytology in the diagnosis of mucinous pancreatic cystic lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2756-2766. van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:383-389. Khalid A, Zahid M, Finkelstein SD, et al. Pancreatic cyst fluid DNA analysis in evaluating pancreatic cysts: a report of the PANDA study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1095-1102. Sawhney MS, Devarajan S, O’Farrel P, et al. Comparison of carcinoembryonic antigen and molecular analysis in pancreatic cyst fluid. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1106-1110. Singhi AD, Nikiforova MN, Fasanella KE, et al. Preoperative GNAS and KRAS testing in the diagnosis of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4381-4389. Layfield LJ, Ehya H, Filie AC, et al. Utilization of ancillary studies in the cytologic diagnosis of biliary and pancreatic lesions: the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology guidelines. Cytojournal. 2014;11(suppl 1):4. Thornton GD, McPhail MJ, Nayagam S, Hewitt MJ, Vlavianos P, Monahan KJ. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration for the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:48-57. Lee HJ, Kim MJ, Choi JY, Hong HS, Kim KA. Relative accuracy of CT and MRI in the differentiation of benign from malignant pancreatic cystic lesions. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:315-321. Visser BC, Yeh BM, Qayyum A, Way LW, McCulloch CE, Coakley FV. Characterization of cystic pancreatic masses: relative accuracy of CT and MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:648656. Sainani NI, Saokar A, Deshpande V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Hahn P, Sahani DV. Comparative performance of MDCT and MRI with MR cholangiopancreatography in characterizing small pancreatic cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:722-731. Gillis A, Cipollone I, Cousins G, Conlon K. Does EUS-FNA molecular analysis carry additional value when compared to Cancer Cytopathology April 2016 Cytology of Pancreatic Mucinous Cysts/Smith et al cytology in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasm?. A systematic review. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:377-386. 31. Panarelli NC, Sela R, Schreiner AM, et al. Commercial molecular panels are of limited utility in the classification of pancreatic cystic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1434-1443. 32. Pitman MB, Yaeger KA, Brugge WR, Mino-Kenudson M. Prospective analysis of atypical epithelial cells as a high-risk cytologic feature for malignancy in pancreatic cysts. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013; 121:29-36. Cancer Cytopathology April 2016 33. Pitman MB, Centeno BA, Genevay M, Fonseca R, MinoKenudson M. Grading epithelial atypia in endoscopic ultrasound– guided fine-needle aspiration of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: an international interobserver concordance study. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:729-736. 34. Layfield LJ, Dodd L, Factor R, Schmidt RL. Malignancy risk associated with diagnostic categories defined by the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology pancreaticobiliary guidelines. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:420-427. 293