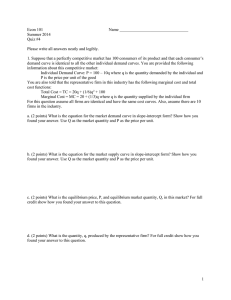

Undergraduate study in Economics, Management, Finance and the Social Sciences Introduction to economics O. Birchall with D. Verry, M. Bray and D. Petropoulou EC1002 2022 Introduction to economics O. Birchall with D. Verry, M. Bray and D. Petropoulou EC1002 2022 Undergraduate study in Economics, Management, Finance and the Social Sciences This subject guide is for a 100 course offered as part of the University of London undergraduate study in Economics, Management, Finance and the Social Sciences. This is equivalent to Level 4 within the Framework for Higher Education Qualifications in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (FHEQ). For more information, see: www.london.ac.uk This guide was prepared for the University of London by: O. Birchall with D. Verry, M. Bray and D. Petropoulou, The London School of Economics and Political Science. This is one of a series of subject guides published by the University. We regret that due to pressure of work the authors are unable to enter into any correspondence relating to, or arising from, the guide. If you have any comments on this subject guide please communicate these through the discussion forum on the virtual learning environment. University of London Publications Office Stewart House 32 Russell Square London WC1B 5DN United Kingdom https://london.ac.uk/ Published by: University of London © University of London 2022. The University of London asserts copyright over all material in this subject guide except where otherwise indicated. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. We make every effort to respect copyright. If you think we have inadvertently used your copyright material, please let us know. Contents Contents Introduction............................................................................................................. 1 Introduction to the subject area...................................................................................... 1 Aims of the course.......................................................................................................... 1 Learning outcomes......................................................................................................... 2 Overview of learning resources....................................................................................... 2 Route map to the guide.................................................................................................. 4 Study advice................................................................................................................... 5 Use of mathematics........................................................................................................ 6 Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis......................... 7 Introduction................................................................................................................... 7 Scarcity........................................................................................................................ 10 Rationality.................................................................................................................... 11 The production possibility frontier (PPF)......................................................................... 11 Opportunity cost and absolute and comparative advantage........................................... 12 Markets........................................................................................................................ 14 Microeconomics and macroeconomics.......................................................................... 15 A note on mathematics................................................................................................ 15 Models and theory........................................................................................................ 16 Criticisms of economics ............................................................................................... 19 Overview...................................................................................................................... 19 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................... 20 Sample questions......................................................................................................... 20 Block 2: Demand, supply and the market.............................................................. 23 Introduction................................................................................................................. 23 Equilibrium................................................................................................................... 24 Demand and supply curves........................................................................................... 25 Shifts in the demand and supply curves......................................................................... 26 Consumer and producer surplus.................................................................................... 27 Overview...................................................................................................................... 28 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................... 29 Sample questions......................................................................................................... 29 Block 3: Elasticity.................................................................................................. 31 Introduction................................................................................................................. 31 Price elasticity of demand ............................................................................................ 32 Cross-price elasticity of demand.................................................................................... 36 Income elasticity of demand......................................................................................... 36 Price elasticity of supply................................................................................................ 37 Incidence of a tax ........................................................................................................ 37 Overview...................................................................................................................... 38 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................... 39 Sample questions......................................................................................................... 39 Block 4: Consumer choice...................................................................................... 41 Introduction................................................................................................................. 41 Consumer choice and demand decisions....................................................................... 42 Utility maximisation and choice..................................................................................... 45 i EC1002 Introduction to economics Income and price changes............................................................................................ 47 Deriving demand: ‘The individual demand curve’........................................................... 48 Deriving demand: ‘The market demand curve’............................................................... 50 Complements and substitutes....................................................................................... 50 Overview...................................................................................................................... 51 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................... 52 Sample questions......................................................................................................... 52 Block 5: The firm.................................................................................................... 55 Introduction................................................................................................................. 55 Introduction to the firm................................................................................................ 56 The firm’s supply decision............................................................................................. 56 Profit = Total revenue – Total cost................................................................................. 62 Cost, production and output......................................................................................... 65 Overview...................................................................................................................... 70 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................... 71 Sample questions......................................................................................................... 71 Block 6: Perfect competition ................................................................................ 73 Introduction................................................................................................................. 73 Assumptions and implications....................................................................................... 74 The firm’s supply decision............................................................................................. 75 Industry supply curves................................................................................................... 78 Comparative statics ..................................................................................................... 78 Perfect competition and efficiency................................................................................. 79 Overview...................................................................................................................... 80 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................... 81 Sample questions......................................................................................................... 81 Block 7: Pure monopoly......................................................................................... 83 Introduction................................................................................................................. 83 Perfect competition and perfect monopoly..................................................................... 84 Monopoly analysis........................................................................................................ 84 Social cost of monopoly................................................................................................ 88 Price discrimination...................................................................................................... 89 When can monopolies be justified?............................................................................... 90 Overview...................................................................................................................... 90 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................... 91 Sample questions......................................................................................................... 91 Block 8: Market structure and imperfect competition.......................................... 93 Introduction................................................................................................................. 93 A theory of market structure......................................................................................... 94 Monopolistic competition............................................................................................. 95 Oligopoly..................................................................................................................... 96 Game theory................................................................................................................ 96 Models of oligopoly...................................................................................................... 97 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 100 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 100 Block 9: The labour market.................................................................................. 105 Introduction............................................................................................................... 105 The factors of production............................................................................................ 107 Analysis of the labour market...................................................................................... 107 Labour supply............................................................................................................. 110 ii Contents Labour market equilibrium ......................................................................................... 111 Disequilibrium in the labour market............................................................................ 112 Overview.................................................................................................................... 113 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 114 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 114 Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government................................. 117 Introduction............................................................................................................... 117 Equity and efficiency................................................................................................... 120 Distortion of the market.............................................................................................. 123 Sources of market failure............................................................................................ 124 Taxes and externalities................................................................................................ 126 Public goods............................................................................................................... 126 Overview.................................................................................................................... 128 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 128 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 128 Block 11: Introduction to macroeconomics......................................................... 131 Introduction............................................................................................................... 131 Macroeconomic analysis............................................................................................. 132 The circular flow of income......................................................................................... 132 Measuring GDP.......................................................................................................... 134 Overview.................................................................................................................... 137 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 137 Sample questions ...................................................................................................... 138 Block 12: Supply-side economics and economic growth.................................... 141 Introduction............................................................................................................... 141 Supply-side economics................................................................................................ 142 Economic growth....................................................................................................... 143 Inputs to production................................................................................................... 144 Solow growth model.................................................................................................. 144 Romer’s model of endogenous growth........................................................................ 149 Costs of growth.......................................................................................................... 150 Overview.................................................................................................................... 151 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 151 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 152 Block 13: Output and aggregate demand........................................................... 153 Introduction............................................................................................................... 153 Components of aggregate demand: consumption and investment............................... 154 Equilibrium output...................................................................................................... 155 The multiplier............................................................................................................. 156 Foreign trade: exports and imports.............................................................................. 159 Overview.................................................................................................................... 160 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 161 Sample questions ...................................................................................................... 161 Block 14: Money and banking; interest rates and monetary transmission......... 163 Introduction............................................................................................................... 163 Money and banking.................................................................................................... 164 Financial crises........................................................................................................... 164 Demand for money..................................................................................................... 164 Money market equilibrium and monetary control......................................................... 165 Monetary policy: targets, instruments and the transmission mechanisms...................... 165 iii EC1002 Introduction to economics Overview.................................................................................................................... 166 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 167 Sample questions ...................................................................................................... 167 Block 15: Monetary and fiscal policy.................................................................. 169 Introduction............................................................................................................... 169 Monetary policy.......................................................................................................... 170 The IS-MP model........................................................................................................ 170 Deriving the IS curve................................................................................................... 171 The MP curve............................................................................................................. 172 The IS-MP in action.................................................................................................... 173 Overview.................................................................................................................... 174 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 174 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 174 Block 16: Aggregate demand and aggregate supply.......................................... 177 Introduction............................................................................................................... 177 Aggregate demand..................................................................................................... 178 Aggregate supply....................................................................................................... 179 Equilibrium inflation................................................................................................... 180 Wage rigidity.............................................................................................................. 181 Short-run aggregate supply......................................................................................... 181 Adjustment to demand shocks.................................................................................... 182 Overview.................................................................................................................... 184 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 185 Sample questions ...................................................................................................... 185 Block 17: Inflation............................................................................................... 187 Introduction............................................................................................................... 187 Money and inflation................................................................................................... 187 The Phillips curve and inflation expectations................................................................ 188 The costs of inflation.................................................................................................. 191 Controlling inflation.................................................................................................... 192 Overview.................................................................................................................... 192 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 193 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 193 Block 18: Unemployment.................................................................................... 195 Introduction............................................................................................................... 195 Rates of unemployment.............................................................................................. 196 Analysis of unemployment ......................................................................................... 197 Changes in unemployment......................................................................................... 199 Cyclical unemployment............................................................................................... 200 Cost of unemployment............................................................................................... 201 Overview.................................................................................................................... 201 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 202 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 202 Block 19: Exchange rates and the balance of payments..................................... 205 Introduction............................................................................................................... 205 The exchange rate...................................................................................................... 206 The balance of payments............................................................................................ 208 Real and PPP exchange rates...................................................................................... 208 The current and financial accounts.............................................................................. 210 Long-run equilibrium.................................................................................................. 211 iv Contents Overview.................................................................................................................... 211 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 212 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 212 Block 20: Open economy macroeconomics......................................................... 215 Introduction............................................................................................................... 215 The macroeconomy under fixed exchange rates........................................................... 215 Devalution of a fixed exchange rate............................................................................ 216 The macroeconomy under floating exchange rates....................................................... 217 Overview.................................................................................................................... 219 Reminder of learning outcomes.................................................................................. 219 Sample questions....................................................................................................... 219 v EC1002 Introduction to economics Notes vi Introduction Introduction Introduction to the subject area Every day people make decisions that belong within the realm of economics. What to buy? What to make and sell? How many hours to work? We have all participated in the economy as consumers, many of us as workers, some of us also as producers. We have paid taxes. We have saved our earnings in a bank account. All of these activities (and many more) belong to the realm of economics. Households and firms are the basic units of an economy and are concerned with the economic problem: how best to satisfy unlimited wants using the limited resources that are available? As such, economics is the study of how society uses its scarce resources. Its aim is to provide insight into the processes governing the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services in an exchange economy. The previous paragraph could be taken to imply that the ‘realm of economics’ is limited and clearly defined. However, if we view economics as a way of thinking, or a set of tools that can be applied to analyse human behaviour and the world around us, then you will find that the principles of economics can be applied to many different areas of life. The scope is thus very broad, but the principles of analysis are well defined, and these are what you will become familiar with through undertaking this course. Although the course provides some information that is descriptive, its main focus is on introducing models and concepts which are used as tools of economic analysis. Concepts such as opportunity cost and approaches such as marginal analysis can be widely applied and prove very useful in understanding various aspects of society and people’s lives. The study of economics does not just impart knowledge; it also develops skills such as logical and analytical thinking and problem-solving capabilities, which are useful beyond the formal study of economics. For some of you, economics is not the main area of study, and you may not be intending to pursue a career as an economist. However, we are sure that an understanding of fundamental economic concepts will prove useful to you in whatever direction your studies and subsequent career may take. Aims of the course The course aims to: • introduce you to an understanding of the domain of economics as a social theory • introduce you to the main analytical tools and reasoning used in economic analysis • introduce you to the main conclusions derived from economic analysis and to develop your understanding of their organisational and policy implications • enable you to participate in debates on economic matters. 1 EC1002 Introduction to economics Learning outcomes At the end of the course and having completed the essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • define key concepts and describe the models and methods used in economic analysis • formulate real world issues in the language of economic modelling • apply and use economic models to analyse these issues • assess the potential and limitations of the models and methods used in economic analysis. Overview of learning resources Textbooks This subject guide follows the structure of the essential textbook and works through the parts of the textbook included in the syllabus section by section, providing commentary, additional questions and extending the material in some parts. Begg, D., G. Vernasca, S. Fischer and R. Dornbusch Economics. (London: McGraw Hill, 2020) 12th edition [ISBN 9781526847393]. Referred to as BVFD. Earlier editions are also useful but you will find differences. In particular, this course covers the IS-MP model as a key framework of macroeconomic analysis, whereas earlier editions focus on the IS-LM model. How to use the subject guide Each of the 20 blocks of the subject guide covers one or two chapters from the primary textbook. The guide works through the textbook section by section and you will find additional explanations and questions to aid and test your understanding. The subject guide has been designed to accompany the textbook, so you should use them jointly and follow the reading instructions listed throughout. One key aim of the guide is to encourage active engagement with the material, as this is how you will gain a good understanding. For example, many of the models which will be covered in this course are expressed graphically and the subject guide contains empty boxes where you can practise drawing these graphs. It is very difficult to understand and remember graphs just by looking at them, so you will need to practise drawing them for yourself. For more complex graphs in later chapters, you could even practise using blank paper and then, when you are confident, draw the graph in the empty box in the subject guide. You are also encouraged to actively undertake the other activities and questions in the subject guide. Answers to these are available on the virtual learning environment (VLE). The subject guide and the primary textbook must be used together. The guide will not make much sense without the textbook. Equally, do not be tempted to neglect the guide and just focus on the textbook. You need to be aware that the subject guide not only seeks to complement and clarify the contents of the textbook, but also to extend it in certain places. For the final examination, you will need to be familiar with the material in both the textbook and the subject guide. Textbook chapters that are not referred to in the guide and are not examinable. We hope that this guide will help you as you work through the textbook and that you will find it useful in your studies. 2 Introduction Online study resources (VLE, Online Library) In addition to the subject guide and the Essential reading, it is crucial that you take advantage of the study resources that are available online for this course, including the VLE and the Online Library. You can access the VLE, the Online Library and your University of London email account via the Student Portal at: https://my.london.ac.uk You should have received your login details for the Student Portal with your official offer, which was emailed to the address that you gave on your application form. You have probably already logged in to the Student Portal in order to register! As soon as you registered, you will automatically have been granted access to the VLE, Online Library and your fully functional University of London email account. If you have forgotten these login details, please click on the ‘Forgotten your password’ link on the login page. The VLE The VLE, which complements this subject guide, has been designed to enhance your learning experience, providing additional support and a sense of community. It forms an important part of your study experience with the University of London and you should access it regularly. The VLE provides a range of resources for EMFSS courses: • Course materials: Subject guides and other course materials available for download. In some courses, the content of the subject guide is transferred into the VLE and additional resources and activities are integrated within the text. • Readings: Direct links, wherever possible, to essential readings in the Online Library, including journal articles and ebooks. • Video content: Including introductions to courses and topics within courses, interviews, lessons and debates. • Screencasts: Videos of PowerPoint presentations, animated podcasts and on-screen worked examples. • External material: Links out to carefully selected third-party resources. • Self-test activities: Multiple-choice, numerical and algebraic quizzes to check your understanding. • Collaborative activities: Work with fellow students to build a body of knowledge. • Discussion forums: A space where you can share your thoughts and questions with fellow students. Many forums will be supported by a ‘course moderator’, a subject expert employed by LSE to facilitate the discussion and clarify difficult topics. • Past examination papers: We provide up to three years of past examinations alongside Examiners’ commentaries that provide guidance on how to approach the questions. • Study skills: Expert advice on getting started with your studies, preparing for examinations and developing your digital literacy skills. Note: Students registered for Laws courses also receive access to the dedicated Laws VLE. Some of these resources are available for certain courses only, but we are expanding our provision all the time, and you should check the VLE regularly for updates. 3 EC1002 Introduction to economics Answers on the VLE Answers to the subject guide exercises can be found on the VLE. By far the most beneficial approach is to attempt the questions and activities yourself before you look at the answers. If, when you do look at them, you discover that your own answer is incorrect, try to work out what led you to that answer (to clear away your misconceptions) and furthermore, try to understand why the given answer is in fact correct. This will help you to gain a solid understanding. Making use of the Online Library The Online Library (http://onlinelibrary.london.ac.uk) contains a huge array of journal articles and other resources to help you read widely and extensively. To access the majority of resources via the Online Library you will either need to use your University of London Student Portal login details, or you will be required to register and use an Athens login. The easiest way to locate relevant content and journal articles in the Online Library is to use the Summon search engine. If you are having trouble finding an article listed in a reading list, try removing any punctuation from the title, such as single quotation marks, question marks and colons. For further advice, please use the online help pages (http://onlinelibrary. london.ac.uk/resources/summon) or contact the Online Library team: onlinelibrary@shl.london.ac.uk Route map to the guide The subject guide consists of 20 blocks – an introductory block, and then 9 for microeconomics and macroeconomics, respectively. Throughout the guide, ‘chapter’ refers to the sections of the textbook, while ‘block’ refers to the sections of the subject guide. This is to avoid confusion – for example, when the guide says ‘this concept will be explored further in Chapter 12’, it should be clear to the reader that this refers to Chapter 12 of the textbook (BVFD). Introduction and Microeconomics 4 Block Title BVFD Chapter 1 Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis 1,2 2 Demand, supply and the market 3 3 Elasticity 4, 15.3, Maths 15.1 4 Consumer choice 5 (except 5.6) 5 The firm 7, 8 6 Perfect competition 9.1–9.4 7 Pure monopoly 9.5–9.10 8 Market structure and imperfect competition 10 (except 10.6 and A10.2) 9 The labour market 11 (except 11.8) 10 Welfare economics and the role of government 14 (except 14.7 and 14.8); 15.2–15.3, Maths 15.3 Introduction Macroeconomics Block Title BVFD Chapter 11 Introduction to macroeconomics 17 12 Supply-side economics and economic growth 18 13 Output and aggregate demand 19, 20 14 Money and banking; interest rates and monetary transmission 21 (except Maths 21.2, 22 (except Maths 22.1) 15 Monetary and fiscal policy 23 (except 23.6 and the appendix) 16 Aggregate demand and aggregate supply 24 17 Inflation 25 (except 25.1) 18 Unemployment 26 (except Maths 26.1) 19 Exchange rates and the balance of payments 27(except Maths A27.1) 20 Open economy macroeconomics 28 (except Maths 28.1) Study advice The British education system, possibly more than others, and economics as a subject, possibly more than others, both emphasise understanding above rote learning (learning by heart). It is very difficult (if not impossible) to do well in economics examinations simply by rote learning. A much better strategy is to try to gain a good understanding of the concepts and the models. Although this may involve more work in the short term, the final outcome will be much better, and the examination much easier. For example, many of the models we will cover can be summarised in a single graph or set of equations. You will need to be able to use these graphs to demonstrate the effects of changes in the economic environment to which the model relates. This is very difficult to do well through memorisation, but if you understand why the different lines of the graph are drawn in that particular way or what a particular equation represents, then adjusting the graph or modifying the equations will become a relatively simple and straightforward exercise. The textbook, which the subject guide accompanies, assumes that you haven’t done any economics before and starts from the basics. It gives a good explanation of all concepts and uses examples to make these new concepts intuitive. It also includes material to stretch you, including Maths boxes. You are required to really master this textbook, including the Maths boxes and more challenging elements. If there are sections which are difficult to understand at first, you may find that reading these through several times is very helpful. In certain places, the subject guide will also seek to extend the textbook if there are areas where it does not go far enough. Although you will find the textbook approach of starting at a fairly basic level very useful, you should expect the examination to be quite rigorous. At the end of each block, you will find (i) two to three multiple choice questions for you to check your basic understanding, (ii) two to three True/False/Uncertain questions similar in style to Section A of the examination, and (iii) one long question similar in style to Section B of the examination. Working through these end of block questions and then attempt past examination questions is an important part of your preparation for the course. In this way, we hope to help you really lay a firm foundation of understanding in economics, and at the same time 5 EC1002 Introduction to economics demonstrate the high standard that is expected of you as University of London students. In the subject guide you will find six ‘food for thought’ boxes. These are designed to help you engage with the material by relating some of the theoretical ideas to real world issues and point you towards further reading you may find interesting. There will be occasional opportunities to bring in ideas from the boxes into examination answers but note the further materials accessible through the links are not directly examinable. Box 1: Why do consumers experience regret? (Block 4) Box 2: Should wages be fair? (Block 8) Box 3: Why is climate change such a challenge? (Block 10) Box 4: How should we measure the wellbeing of nations? (Block 11) Box 5: Is Bitcoin money? (Block 14) Box 6: What will the future of work look like? (Block 18) Use of mathematics Economic models can be expressed in various ways, in words, in diagrams and in equations. Although this course mainly uses diagrammatic representations accompanied by words, simple equations can also be a concise way of expressing an economic model, and you will need to become familiar with this approach. At this stage, the maths involved will be limited to simple algebra and elementary calculus. Some basic mathematical techniques and ideas will be also introduced in the first block. It is important to work through the Maths boxes in each chapter, as these often provide a step-by-step explanation of the mathematical approach to the models covered. The subject guide will also provide further explanations where we think this will be helpful. Economics is becoming an increasingly technical subject and, although the level of mathematics required for this course is quite basic, we hope that you will become confident in taking a mathematical approach to analysing economic issues. 6 Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis Introduction Block 1 is an introduction to the course. It contains a brief discussion of several ideas which you will study in more detail later this course. You do not need to study this block in detail, but you will need to take note of certain specific issues. These are indicated with the label Important. This block covers the first two chapters of the textbook and is designed to give you an introduction to economics and some help in starting to use the tools of economic analysis. The concepts introduced in this block, such as scarcity, opportunity cost and ceteris paribus (more on these below), are absolutely essential to your understanding of economics. The more thoroughly you work through the material in this block, the better your foundation will be for all the material that follows. So what is economics? The word ‘economy’ comes from two Greek words – oikos (meaning house) and nemein (meaning manage) – its original meaning was ‘household management’. Households have limited resources and managing these resources requires many decisions and a certain organisational system. The meaning of the word economics has developed over time. Today, economics can be defined as the study of how societies make choices on what, how and for whom to produce, given the limited resources available to them. Furthermore, the key economic problem can be defined as being to reconcile the conflict between people’s virtually unlimited desires and the scarcity of available resources and means of production. These are the definitions provided in the core textbook (BVFD) and indeed in many other textbooks. They are traditional definitions and have their origins in an essay by Lionel Robbins (of the London School of Economics and Political Science) written in 19321 in which he defined economics as ‘the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses’. It is important to realise that this definition is not without its critics. The textbook does not pretend to discuss in any depth the definition of economics or the legitimate domain of economic investigation. Those wishing to pursue the philosophical foundations of the nature of economics could consult the collection of papers edited by Frank Cowell and Amos Witztum,2 especially papers by Atkinson, Witztum, Backhouse and Medema. On a less philosophical note, if we were to follow the definition attributed to Jacob Viner (an early member of the ‘Chicago School’ and a teacher of Nobel laureate Milton Friedman) that ‘economics is what economists do’, the Robbins definition stated above would fall short of describing the way in which the subject has evolved, in particular in its failure to reflect the time and effort devoted today to empirical analysis. Arguably, the definitions provided in the textbook apply more directly to microeconomics than macroeconomics, the latter being more concerned with the structure and performance of the aggregate economy and such issues as growth, cycles, unemployment and inflation. However, Lionel Robbins An essay on the nature and significance of economic science. (London: Macmillan, 1932, 2nd edition 2014) p.16. 1 Cowell, Frank and Amos Witztum (eds) Lionel Robbins’s essay on the nature and significance of economic science: 75th anniversary conference proceedings. (London: Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines, 2009) pp.1–500. Available at http://darp. lse.ac.uk/papersdb/ LionelRobbinsConference ProveedingsVolume.pdf 2 7 EC1002 Introduction to economics underlying these ‘big’ issues is the behaviour of individual agents such as consumers and firms. Recent developments in macroeconomics have been concerned with establishing microeconomic foundations. So scarcity and the rational responses to it are not absent from macroeconomics. Although the definitions above may appear abstract, economics deals with phenomena you will be very familiar with from your daily activities, and provides tools and a language to analyse these. While it is not the only language available, we hope it will prove useful to you. Economics and the real world One of the main reasons that BVFD was chosen as the textbook for the course is that it combines the exposition of economic theory with liberal use of actual data on many economic issues. Modern economics is a subject which, at its best, does not theorise in a vacuum but addresses issues of real world importance and attempts to make its concepts and theories consistent with the facts. When economists make policy recommendations these address issues of current importance and concern. Furthermore, the effectiveness of economic policy is increasingly subject to empirical evaluation. Sometimes this happens by piloting a policy on a restricted scale before it is rolled out nationally. Almost always government departments, private sector analysts and academic economists attempt to evaluate the consequences of policy in the months or years after implementation. If you pursue your study of economics to a more advanced level you will learn how applied economists attempt to test the relevance and accuracy of their theories and the success or failure of economic policy using statistical techniques broadly known as econometrics. However, even at this early stage of your study you should attempt to familiarise yourself with actual facts about the economy and think about what these imply for economic theory and the formation and evaluation of economic policy. The statistics and policy discussions in BVFD often (but not always) relate to the UK economy; we encourage you to look for comparable examples wherever you live. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: 8 • recognise economics as the study of how society addresses the conflict between unlimited desires and scarce resources • describe ways in which society decides what, how and for whom to produce • identify the opportunity cost of a decision or action • explain the difference between positive and normative economics • define microeconomics and macroeconomics • explain why theories deliberately simplify reality • recognise time-series, cross section and panel data • construct index numbers • explain the difference between real and nominal variables • build a simple theoretical model • plot data and interpret scatter diagrams • use ‘other things equal’ to ignore, but not forget, some aspects of a problem in order to focus on core issues. Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapters 1 and 2. Synopsis of this block This block introduces some of the key concepts in economics. First, scarcity – the idea that the means available to society (its labour force, its capital stock, its natural resources, its technology) are insufficient to meet all the wants (or the desired goods and services) of the people making up that society. Related to scarcity is the concept of opportunity cost – which is the value of the best alternative that must be sacrificed. The concept of scarcity gives rise to the production possibility frontier (PPF), which shows the maximum amount of one good that can be produced given the output of another good. The slope of the PPF is the opportunity cost. The fact that different individuals and countries have different opportunity costs of producing various goods gives rise to comparative advantage and creates the possibilities for gains from trade. In economics, people are assumed to behave rationally – only taking a course of action if its benefits outweigh its costs. Furthermore, people are assumed to be motivated by self-interest. The idea of the ‘invisible hand’ describes how market forces allocate resources efficiently despite the self-interested motivations of individuals. Markets resolve production and consumption decisions via the adjustment of prices. Economics can be divided into different sub groups and approaches. Positive economics deals with ‘facts’ about how the economy behaves and with empirically testable propositions, while normative economics involves subjective judgements. Microeconomics studies particular markets and activities in detail, while macroeconomics deals with aggregates and studies the economy as a whole system. The interplay of data and theory/models in economics is very important. Models are deliberate simplifications of reality which help organise how we think about a problem. A key approach of economic analysis is to abstract from various factors by holding them constant – this is known as ceteris paribus or ‘other things equal’. The second half of this block examines the relationship between data and theory and also provides guidance and instruction regarding key practical concepts and skills such as index numbers, nominal and real variables, measuring change, diagrams, lines and equations. Chapter 2 concludes by briefly addressing some popular criticisms of economics and economists. ► BVFD: read Chapter 1. Important: This reading introduces the concept of opportunity cost. You will meet opportunity cost in the context of the firm in Block 5. Sections 1.1 and 1.3 introduce the concepts of scarcity, opportunity cost, and efficiency. These are not separate concepts but are all interrelated and can be demonstrated using the production possibility frontier introduced in section 1.3. Read section 1.1, concept 1.1 and case 1.1. 9 EC1002 Introduction to economics Scarcity BVFD defines scarcity by saying: ‘a resource is scarce if the demand for that resource at a zero price would exceed the available supply’. Since the concepts of demand and supply have not yet been introduced to you, we can also define scarcity by stating that the means available to society (its labour force, its capital stock, its natural resources, its technology) are insufficient to meet all the wants (or the desired goods and services) of the people making up that society. This implies that for any one person to have more of something, they or someone else must have less of something else. In turn, this requires choice, both at the level of the individual agent but also at the societal or collective level. How individuals and societies cope with scarcity in relation to wants is central to economics. This course concentrates on the market economy as the basic organisational principle for coping with scarcity, but modified by governments to rectify market shortcomings and to achieve distributional ends. Opportunity cost Related to scarcity is the concept of opportunity cost – one of the key concepts in economic analysis. To cement your understanding of opportunity cost, complete the following activity on this concept. Activity SG1.1 a. Let us change the details of the problem in concept box 1.1. Suppose that there were no jobs in the campus shop. The only job available, and this is the alternative to going to the beach with your friends, is to work at the local fast food restaurant clearing tables and washing dishes. This job also pays £70, but because of its general unpleasantness you wouldn’t do it unless you were paid at least £55. Should you go to the beach or work at the fast food restaurant? b. A high-end ladies fashion boutique purchases winter coats from a manufacturer at a price of £300 per coat. During the winter the boutique will try to sell the coats at a price higher than £300 but may not be able to sell all of the coats. Since they are the latest fashion, no customers would be interested in buying the coats next season. However, at the end of the winter, the manufacturer will pay the boutique 20% of the original price for any unsold coats (and re-use the expensive fabrics they are made from for the next year’s designs). i. At the beginning of the year, before the boutique has purchased any coats, what is the opportunity cost of these coats? ii. After the boutique has purchased the coats, what is the opportunity cost associated with selling a coat to a prospective customer? (You can assume the coat will be unsold at the end of the winter if that customer doesn’t buy the coat). iii. Suppose towards the end of the winter the boutique still has a large inventory of unsold coats. The boutique has set a retail price of £950 per coat. The marketing manager argues that the boutique should cut the price to £199 to try to sell the remaining coats before they become unfashionable at the end of the winter. However, the general manager disagrees, arguing that would mean a loss of £101 on each coat. Which makes more economic sense – the marketing manager’s suggestion or the general manager’s argument? ► BVFD: read section 1.2. This section raises various economic issues which you may be familiar with through the news or other sources. It demonstrates what kinds of issues economics deals with. 10 Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis In each case, the authors demonstrate the impact on the three key questions of what to produce, how to produce it and for whom. The global financial crisis of 2007–09 was a time of great disruption to economies around the world and indeed to the world economy. As can be seen in Figure 1.1 of the textbook, the US economy shrank at a faster rate than had been seen since before the 1980s. Rationality ► BVFD: read concept box 1.2. This concept box comes back to the idea of rationality, introduced in section 1.1 of the textbook. In much of economic analysis people are assumed to act rationally, using all available information to maximise their satisfaction. In the real world, human behaviour is complex. The field of behavioural economics examines human behaviour, especially when it appears to depart from the assumption of rationality. Chapter 2.10 concludes with some criticisms of economics, including the criticisms that ‘people are not as mercenary as economists think’. In fact, depending on the task at hand, behaviour can be modelled very simply, or in a more complex way to include various other factors, including altruism. In some cases, even very simple models can go a long way in explaining human behaviours. When these fail, more complex elements can be included to make the model more realistic. Behavioural economics indicates some ways that the simple assumption of rationality can be extended to provide further insights into human behaviour. The production possibility frontier (PPF) ► BVFD: read section 1.3. The production possibility frontier is one of the most fundamental and important concepts in economics. It shows all the combinations of goods that can be produced if the means of production are fully employed. It will come up again in Block 6 when we discuss the perfect competition model of market structure, Block 10 when we discuss welfare economics and also in Block 12 when we discuss economic growth. The PPF: scarcity and desirability The PPF is a boundary. It demonstrates scarcity in that any point beyond the frontier is unattainable. Society cannot produce combinations that lie outside the PPF because there are insufficient resources to do so. The economic problem has been defined as reconciling scarcity with people’s virtually limitless desires. These desires mean that people wish to have more of everything – as such, points above and to the right of the origin are seen as better than points closer to the origin. If society produces at a point on the frontier rather than inside it, society will be better off. The PPF and efficiency The statements above relate to the idea of efficiency. Points on the PPF are productive efficient, while points within the curve are inefficient. An efficient allocation of means of production is one which yields a combination of outputs where it is not possible to increase the output of one good without reducing the output of the other.3 Societies must also choose not just any point on the PPF but a specific point. This relates to allocative efficiency and will be discussed further in Block 10. For simplicity, we assume all goods in the economy are grouped into two groups, or that it is a two-good economy. 3 11 EC1002 Introduction to economics The PPF and opportunity cost Society has a given amount of resources at its disposal and when the economy is using these efficiently, using more resources to increase the production of one good necessarily implies decreasing the production of the other. This trade-off helps demonstrate the idea of opportunity cost. The amount by which good B is reduced to increase the production of good A is the opportunity cost of increasing the production of good A. Moving along the PPF from one point on the curve to another shows how much of one good must be given up to increase the production of the other – thus the slope of the PPF is the opportunity cost. The opportunity cost can also be described as the real price of a good, since it represents the amount of one good that must be sacrificed in order to attain more of the other. The shape of the PPF and marginal analysis In economics, marginal analysis is very important. ‘Marginal’ simply means ‘extra’ or ‘additional’ and marginal analysis has to do with decision making at the margin. Economists often analyse the effects of a one unit change in something – for example: how much better off will a consumer be if they can purchase one additional unit of a good? How much extra profit will a company earn by producing one additional unit of a good? How much more can a company produce if they hire one additional worker? Asking such questions helps to find the optimal level of (for example) consumption and production, and you will come across this again and again throughout the course. For example, Block 4 introduces the idea of diminishing marginal utility: the first glass of lemonade you drink on a hot day is very refreshing, the second is less so, and by the time you finish the third, you may not want to drink any more lemonade for a while. In this block, the shape of the PPF is linked to diminishing marginal returns: in the example given in section 1.3, the first worker employed in the film industry produces 9 units of output, the second produces 8 units, the third produces 7 units and the fourth produces only 6 units. The fact that the extra output each additional input can produce diminishes is one reason why the PPF is concave toward the origin. Activity SG1.2 Draw a production possibility frontier, clearly marking the regions of inefficient production, efficient production and unattainable production. Illustrate how the slope of the PPF represents opportunity cost. Why is the frontier concave to the origin? Opportunity cost and absolute and comparative advantage Important: The ideas of absolute and comparative advantage are fundamental to our understanding of international trade and you should study them carefully at this stage. The concept of opportunity cost can also help us to understand why people (and countries) specialise in the production of certain goods and then trade. Let us expand a bit on the treatment of PPFs in the second part of section 1.3, dealing with the two individuals, Jennifer and John, making the two goods, T-shirts (T) and cakes (C). We can write, for Jennifer: Number of T-shirts produced = (T-shirts produced per hour) * hours spent on T-shirt production (LT). 12 Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis Or Τ = 4LT T ∴ LT = 4 Similarly for Jennifer cake production can be written as: C = 2LC C ∴ LC = 2 Now, we are also told that Jennifer can work up to 10 hours, in T-shirt and/or cake production. When she does work 10 hours: LT + LC = 10 C T + = 10 4 2 T + 2 C = 40 Be sure that you understand that for John we have the equation: 2C + T = 10 These equations will show the production possibilities for Jennifer and John. They will help you in Activity SG1.3 which you should now attempt. Activity SG1.3 a. Putting cakes on the horizontal axis and T-shirts on the vertical axis draw Jennifer and John’s production possibility frontiers for a 10-hour working day. b. In what way do these PPFs differ from that drawn in Figure 1.2? Why? c. Write down the equations of these production possibility frontiers, making T (T-shirts) a function of C (cakes). d. What is the interpretation of the slope of these PPFs? e. In your diagram what represents Jennifer’s absolute advantage in producing both goods? f. In your diagram what represents John’s comparative advantage in making cakes? To cement your understanding of comparative advantage, complete the following. Activity SG1.4 Suppose there are two countries (M and W) and two goods (shoes and hats). The table gives the labour requirements to produce a unit of each output in each country. Country M Country W Shoes 10 labour hrs/unit of output 12 Hats 2 5 a. Which country has an absolute advantage in shoes? In hats? b. Which country has a comparative advantage in shoes? In hats? c. Assuming each country has 100 labour hours available, what will the total production of shoes and hats be if each country specialises fully in the production of the good in which it has a comparative advantage (presumably they would then engage in trade with each other) compared to what they could produce in a situation with no trade if they spent half their available labour on each good? 13 EC1002 Introduction to economics If you are interested in exploring these concepts in more detail you can read Chapter 30 on International Trade (which is optional and will not be covered in this subject guide or examined). Markets ► BVFD: read section 1.4 and case 1.2 and complete activity 1.1. As noted above, economics can be defined as the study of how societies make choices on what, how and for whom to produce. As such, economics is concerned with the organisation of economic activities in a society and the institutional arrangements that will provide optimal answers to the questions above. These institutional arrangements can be thought of as existing along a continuum from, on the one hand, ‘command economies’, where decisions are made centrally by the government planning office, to, on the other hand, ‘free market economies’, where decisions are taken by individual agents driven by self-interest but organised by market forces as by an ‘invisible hand’. This section begins to explain how free markets can often bring about efficient outcomes. In subsequent blocks we will discuss in much greater detail, and with more rigour, how market forces guide resource allocation. Although it is true that centrally planned economies (command economies) were riddled with inefficiencies, it would be incorrect to believe that all non-planned economies are pure market economies. Today we all live in mixed economies, in which governments play a major role. Subsequent chapters (15 and 16) will analyse some of the reasons why markets fail to allocate resources ideally, creating a potential role for the state to step in. The actual extent of state intervention does, of course, differ quite significantly across countries and how large the role of the state should be is a highly contentious issue. Broadly speaking, governments can intervene in the economy either to promote efficient resource allocation where markets fail to achieve this end or to achieve more equitable outcomes than markets generate if left to operate unhindered. Positive and normative economics ► BVFD: read section 1.5. This short section distinguishes in a quite traditional way between positive and normative economics and you should be clear about the distinction. There have been some quite eminent economists, such as the Swedish Nobel Prize winner Gunnar Myrdal who rejected the positive-normative dichotomy, claiming that normative values are inextricably intertwined with so called ‘objective’ or value-free economic analysis. Myrdal argued that economists would be much better advised to state their values openly and explicitly rather than pretend that they could be put to one side while conducting positive analysis. Though this is not the orthodox view in the profession! Returning to the treatment in BVFD, complete the following activity. 14 Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis Activity SG1.5 Classify the following statements as positive or normative: • Inflation is more harmful than unemployment. • An increase in the minimum wage to £11 per hour would reduce employment by 0.5 percentage points. • The government should raise the national minimum wage to £11 per hour to help reduce poverty in society. • An increase in the price of crude oil on world markets will lead to an increase in cycling to work. • A reduction in personal income tax will improve the incentives of unemployed people to find paid employment. • Discounts on alcohol have increased the demand for alcohol among teenagers. • The retirement age should be raised to 75 to combat the effects of our ageing population. Microeconomics and macroeconomics Microeconomics takes a bottom-up approach to studying the economy – focusing on individual consumers, households and firms; while macroeconomics takes a top-down approach, studying the economy as a whole system and focusing on aggregates. One analogy that can be used to describe the difference between macroeconomics and microeconomics is the study of a rainforest. Macroeconomics studies the ecology of the rainforest as a whole, while microeconomics studies individual plants and animals that live there. Most professional economists tend to specialise in either microeconomics or macroeconomics (indeed, they will specialise on sub-fields within this broad dichotomy), though modern macroeconomics builds more heavily on microeconomics, and is what can be called ‘microfounded’. As you work through the textbook and the subject guide you may find yourself drawn either to micro or to macro ahead of the other. That is natural. What you should not do at this stage of your study of economics is unbalance your commitment of time to the two halves; that is not a good strategy, either in terms of doing well in examinations or of building a solid foundation for further study of the subject. Blocks 10 and 11 cover welfare economics and the role of the government. Welfare economics employs microeconomic techniques to analyse welfare at an aggregate (economy-wide) level, and the role of the government is both micro and macro – as governments are involved in specific markets but also attempt to manage the aggregate level of demand and encourage economic stability and growth. For simplicity, therefore, Blocks 10 and 11 are included in the first half of the course on microeconomics. A note on mathematics In discussing the tools of economic analysis, this chapter, perhaps surprisingly, has little to say in general terms about the role of mathematics in economics. In its methods and approaches, if not its subject matter, economics today is almost unrecognisable from the subject taught under the same name 70 or 80 years ago. The transformation has indeed been dramatic. Today, top universities require a high level of mathematical competence of their students, even at undergraduate level (and higher still at postgraduate level), while a cursory scan of the top economics journals might give the impression that the subject is a branch 15 EC1002 Introduction to economics of mathematics. It isn’t. Correctly used, mathematics in economics is a tool – a means to an end not an end in itself. Nevertheless, some have argued that the pervasiveness of mathematics in modern economics has had damaging consequences both on the development of the subject (with concentration on topics that lend themselves to mathematical analysis and relative neglect of those that don’t) and on the ability of economists to communicate with non-economists, often including those responsible for formulating economic policy. Whether or not these criticisms are correct, it is highly unlikely that the trend towards greater reliance on mathematical tools is likely to be reversed in the near future. For those of you pursuing the subject beyond the introductory level you will need to be prepared to use considerably more mathematics. That said, the mathematical requirements of this particular course are fairly limited. You need to be able to do basic arithmetic and algebra, (including solving simultaneous equations) and you need to be able to read and use graphs. Some of the Maths boxes in BVFD use calculus, including partial differentiation and you should certainly try to understand this material. Do not regard the mathematics boxes as optional extras. Models and theory ► BVFD: read the introduction to Chapter 2. The introduction provides a brief but useful argument explaining why models and theory are so important in economics. Sometimes students of introductory economics complain that there is too much theory/too many models. Why can’t the subject just stick to the facts? But which facts? And what can they tell us without guiding principles? On their own the facts are silent. Teamed with appropriate models, however, they can be eloquent. Broadly speaking, two key tools of economic analysis are models/theory and data and they are best deployed in tandem. Someone may notice a certain relationship expressed in economic data and develop a theory to explain this relationship. That theory will then be tested by other data, from different time periods and different contexts – these data will either corroborate the theory, or lead to it being modified or abandoned in favour of a theory that better fits the evidence. In the last 20 years or so, the emphasis has been on identifying and quantifying causal relationships amongst economics variables predicted by theory. Economists do this using a range of empirical techniques, but also heavily through the design and implementation of experiments. Sections 2.1 to 2.5 lay out some important issues relating to economic data, while later sections of the chapter introduce economic models and discuss how models and data are used together in economics. ► BVFD: read sections 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3, as well as concept 2.1. 16 Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis Activity SG1.6 Index numbers: work through the following example to help you understand how index numbers are calculated. Suppose we want to calculate inflation for four specific goods. The index for each good is set at 100 for the first year. Work out the percentage price change in each good (the first one is completed for you). Product Price – year 1 Index – year 1 Price – year 2 Index – year 2 Bread 80p 100 120p 150 Cheese 260p 100 312p Sausages 300p 100 390p Toothpaste 100p 100 80p TOTAL 400/4 Overall index 100 The change in the overall index is the average rate of inflation. What was the rate of inflation for these four products between years 1 and 2? However, the products in the price index are not equally important and should not be given an equal weighting in the calculation of the index. That is why Weighted Index Numbers are often used. Of the four products above, which do you think represents the lowest proportion of a family’s total spending? Which represents the highest? If toothpaste represents a small proportion of each family’s total spending, then we should make the price change for toothpaste have a much smaller overall effect on the price index. To do this we weight each price change to give it more or less importance in the overall index. This has been done in the table below – see if you can complete the last column: Product Weights Price – year 1 Index – year 1 Weighted Price – index – year 2 year 1 Index – year 2 Weighted index – year 2 Bread 4 80p 100 400 120p 150 600 Cheese 2 260p 100 200 312p Sausages 3 300p 100 300 390p Toothpaste 1 100p 100 100 80p TOTAL 10 Overall index 1,000/10 100 What is the rate of inflation between year 1 and 2 once weights are factored in? This figure is considerably higher than the original inflation figure. This is because the products with the highest weights went up in price the most. The effect of the falling price of toothpaste on the overall index was reduced because this item had a very small weight. A weighted index gives a much better estimate of inflation, since it reflects which items are most important to family’s expenditure. ► BVFD: read sections 2.4, 2.5 and concept 2.2. 17 EC1002 Introduction to economics Activity SG1.7 You got a job in the year 2020 with a salary of £35,000. In 2022, you receive a £5,000 increase in your salary. CPI in 2022 with base year 2020 is 108. Calculate your real income in 2020 and 2022 as well as the percentage changes in your nominal income and your real income. ► BVFD: read section 2.6. Economic models are a deliberate simplification of reality. In the same way that an architectural drawing shows all the important features of a house without necessarily looking ‘realistic’, economic models abstract from reality to clarify important features. This helps to simplify and clarify the analysis of the problem at hand. Economic models often use mathematics as the system of logic which ties various parts of the model together. Two terms which you should be familiar with are exogeneity and endogeneity: Following the definitions provided in L&C (glossary), an endogenous variable is a variable that is explained within a model or theory. An exogenous variable influences endogenous variables, but is itself determined by forces outside the model/theory. In the example of a model of London Underground revenue, the number of passengers is an endogenous variable, while factors such as bus fares and passenger incomes are exogenous. Important: If you are not already familiar with section 2.8 on reading diagrams you must study it closely at this stage. ► BVFD: read sections 2.7, 2.8, 2.9 and complete activity 2.1. These sections, and 2.9 below, turn to the use of empirical evidence in economics. They begin to give an intuitive feel for econometrics, the application of statistical and mathematical techniques, often with the help of computers, to economic data, in order to test hypotheses and/or forecast the effects of changes in the economic environment on outcomes of interest (quantity demanded, hours worked, inflation, unemployment, etc.). Econometrics is a central and well developed aspect of the subject, which is generally a required component of an undergraduate degree in economics. However, it is not usually introduced at elementary level. Fitting lines through scatter diagrams – although the term is not provided explicitly in this section, the description of how a computer, programmed to apply defined statistical criteria, quantifies the influences of various factors in a single model is describing multiple regression analysis. The subsection ‘Reading diagrams’ is very basic mathematics, not econometrics. You need to be competent (and confident) in these basic techniques to follow subsequent chapters of the textbook and this subject guide. The following activity enables you to practise basic graphical techniques. Note: Figures 2.4 and 2.5 plot quantity on the vertical axis and price on the horizontal axis. These are simply exercises to teach you techniques for interpreting diagrams and finding the slope and intercept of a line. In the following chapter, demand and supply diagrams will be introduced – typical demand and supply diagrams put price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. Of course, the basic techniques of finding the slope and intercept of the line remain the same. 18 Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis Activity SG1.8 Sketch the following functions, finding the slope and intercept. a. Q=50+20P b. Q=150–10P Criticisms of economics ► BVFD: read section 2.10 and case 2.1. One criticism levied against economics which is mentioned briefly in this section is that ‘the actions of human beings cannot be reduced to scientific laws’. However, if we look at human behaviour in general, we can see stable patterns on average even though the behaviour of individuals is unpredictable. This has to do with the ‘law of large numbers’, a statistical concept or ‘law’ which states that as the number of individual cases increases, random movements tend to offset each other, such that the difference between the expected value and the actual value tends to zero. That means the behaviour of a group of people is much more predictable than the behaviour of certain individuals, because the odd things one individual does tend to be cancelled out by the odd things that some other individual does. Economics has been criticised for failing to predict the financial crisis and associated recession beginning in 2007–08.4 This led to some damage to the reputation of the subject and to the status of the profession. It is too early to say just how damaging this has been (there doesn’t seem to be any major decrease in the demand to study economics at university or, broadly speaking, in the longer-term employment prospects of economics graduates in either the private or public sectors). One consequence of the crisis has been considerable self-examination of the way in which the subject has been taught in the past and the emergence of updated pedagogical approaches can be detected in the design of some introductory courses. Overview Economics analyses what, how and for whom society produces. The key economic problem is to reconcile the conflict between people’s virtually unlimited desires and the scarcity of available resources and means of production. The PPF shows the maximum amount of one good that can be produced given the output of another. The slope of the PPF is the opportunity cost (of the good on the horizontal axis in terms of the other). More generally, opportunity cost is the value of the best alternative that must be sacrificed. The fact that different individuals and countries have different opportunity costs of producing various goods gives rise to comparative advantage and creates the possibilities for gains from trade. Some economists were prescient. Nouriel Roubini (NYU. Stern School of Business) as early as 2006 was predicting that the US housing bubble would burst, leading to damaging loss of consumer confidence and ultimately to recession. Widely criticised for being too pessimistic at the time Roubini’s forecasts were, if anything, exceeded by actual events. The link provides some thoughts of the Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke on the implications of the crisis for economics: www.federalreserve. gov/newsevents/speech/ bernanke20100924a. htm 4 In economics, people are assumed to behave rationally – only taking an action if its benefits outweigh its costs. Furthermore, people are assumed to be motivated by self-interest. The idea of the ‘invisible hand’ describes how, under certain conditions, market forces allocate resources efficiently despite the self-interested motivations of individuals. Markets resolve production and consumption decisions via the adjustment of prices. There is a spectrum of government involvement in the economy – from a command economy to a free market economy. Most industrialised nations have mixed economies. 19 EC1002 Introduction to economics Economics has many dimensions. Positive economics deals with ‘facts’ about how the economy behaves, while normative economics involves subjective judgements. Microeconomics studies particular markets and activities in details, while macroeconomics deals with aggregates and studies the economy as a whole system. The second half of this block examined the relationship between data and theory and provided guidance and instruction regarding key practical concepts and skills such as index numbers, nominal and real variables, measuring change, diagrams, lines and equations. The interplay of data and theory/models in economics is very important. Models are deliberate simplifications of reality which help organise how we think about a problem. Data can indicate a relationship that can be theorised about, and can also be used to quantify relationships and test existing theories. A key approach of economic analysis is to abstract from various factors by holding them constant – this is known as ceteris paribus or ‘other things equal’. Chapter 2 concludes by briefly addressing some popular criticisms of economics and economists, such as the extent of disagreement in the discipline (which in fact often relates more to normative than to positive economics) and assumptions about human behaviour, which are sometimes seen as oversimplified. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. Every summer, New York City puts on free performances of Shakespeare in Central Park. Tickets are distributed on a first-come-first-served basis at 13.00 on the day of the show, but people begin lining up before dawn. Most of the people in the lines appear to be young students, but at the performances most of the audience appears to be made up of older working adults (tickets can be transferred, so the person picking up the tickets does not have to be the person watching the performance). Which of the following concepts best explains this fact? a. Ceteris paribus. b. Opportunity cost. c. Marginal analysis. d. Absolute advantage. 2. The output produced by Samuel and Roberto in 20 labour hours is given below for wine and cheese. Choose the option with the correct statement below. Wine Cheese Samuel 6 4 Roberto 2 3 a. Samuel has an absolute advantage in both products and a comparative advantage in cheese. b. Roberto has an absolute advantage in both products and a comparative advantage in cheese. 20 Block 1: Economics, the economy and tools of economic analysis c. Roberto has an absolute advantage in cheese and a comparative advantage in wine, while the opposite is true for Samuel. d. Samuel has an absolute advantage in both products and a comparative advantage in wine. e. Roberto has an absolute advantage in both products and a comparative advantage in wine. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Some people dislike Marmite (a food spread made from yeast extract, quite popular in the UK), which means that scarcity is not an issue for this good and there is no reason to expand the PPF for Marmite. 2. Sami buys more sweets than olive oil, while Mete buys more olive oil than sweets. If Sami is better than Mete at producing sweets and Mete is better than Sami at producing olive oil, then there are no possible gains from trade between Sami and Mete. Long response question 1. Use the production possibility frontier to illustrate the following concepts: a. scarcity b. opportunity cost c. productive efficiency d. diminishing marginal returns. 21 EC1002 Introduction to economics Notes 22 Block 2: Demand, supply and the market Block 2: Demand, supply and the market Introduction The previous block introduced economics as ‘the study of how societies make choices on what, how and for whom to produce, given the limited resources available to them’ and described how societies adopt various institutional arrangements to answer these questions as best they can. In the societies we all live in, the role of the market is very important as a means of answering these questions. Markets bring together buyers and sellers and the mechanism of prices operates to coordinate the quantities sellers wish to sell with the quantities buyers wish to buy. This chapter examines demand and supply and the way they interact within markets to determine quantities and prices. The focus of this chapter, the demand and supply model, is perhaps the ‘iconic’ model of economics. Like all models it has its shortcomings and knowing when it is appropriate to the analysis of a particular problem, and when it is not, is something of an art. Some of the strengths and weaknesses of this basic model will become clearer in subsequent chapters of the text and blocks in this guide, but first you need to become familiar with the basic workings of the model. Also postponed until later is the analysis of the behaviour of individual consumers and individual firms that lie behind demand and supply curves. It would also be possible to start with the behaviour of these individual agents and then derive the market demand and supply curves, however, experience suggests that the power of supply and demand analysis in showing how prices and quantities respond to changes in the economic environment can also be experienced without all the detailed foundations being in place (as long as they are discussed subsequently) and that this approach is often more motivating than the reverse sequencing. The blocks of the subject guide therefore follow the order of the textbook in firstly presenting the demand and supply model and then showing later how demand and supply curves are derived from the behaviour of individual consumers and firms. Demand is the quantity of a product that buyers wish to purchase at any given price, while supply is the quantity of a product that suppliers are willing to sell at any given price. Demand and supply come together in a market and this determines the price and quantity of goods sold. Since we have all bought (and maybe also sold) goods before, many of these ideas are quite intuitive. Nonetheless, it is important to become familiar with the language economists use to explain these ideas and the way that economics deals with them. Graphical analysis is very important in economics and you will need to become very comfortable with drawing demand and supply curves and using them to demonstrate changes in various influential factors. You will hopefully find this a very useful tool of analysis. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • define the concept of a market • draw demand and supply curves (and inverse demand and supply curves) • find equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity 23 EC1002 Introduction to economics • describe how price adjustment reconciles demand and supply in a market • analyse what shifts demand and supply curves • define reservation prices • describe consumer and producer surplus • analyse excess supply and excess demand • discuss the consequences of imposing price controls • discuss how markets answer what, how and for whom to produce • describe the functions of prices (to ration, to allocate). Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 3. Synopsis of this block This chapter introduces demand and supply and how these come together in a market to determine equilibrium price and quantity. The factors that underlie demand curves and supply curves are outlined, as is the way that a change in one of these factors will lead to a shift in the relevant curve. The concepts of consumer and producer surplus will also be introduced. These exist because there are consumers who would be happy to pay more than the market price, and suppliers who would be happy to sell for less that the market price. The chapter will also show that allowing the market to determine price (rather than having the government impose a price) results in the maximum amount of consumer and producer surplus. Through the readings and the exercises below, these ideas will now be examined in further detail. Equilibrium ► BVFD: read sections 3.1–3.3. Before turning to some activities which will help to consolidate your understanding of the material in these sections it is worth elaborating a little on the concept of equilibrium in economics. You will find that this concept is central in economic theory (whether it is observable in practice raises further issues which we do not address here) although it has many interpretations; even in a basic course such as this you will encounter more than one version. In microeconomics we are about to look at the concept of equilibrium market price, later when we introduce game theory we will encounter the concept of a Nash equilibrium and in macroeconomics we will define equilibrium in terms of aggregate supply and demand (as opposed to the supply and demand in the market for a particular good or service), and in terms of the so-called ‘steady state’ (where capital, investment and output per worker are constant) in growth theory. What is common in all these examples is that the system being analysed is in some sense ‘at rest’ – there are no forces at work generating further changes to the system. In the demand and supply model, an equilibrium price is one where, simultaneously, consumers want to buy just the amount that firms want to sell. At any other price one or other of these groups would want to change the amount they buy or sell. Usually when an economic system is not in equilibrium, there will be incentives for the actors or agents in the model to change their behaviour in ways that move the system towards equilibrium.1 24 In more advanced analysis, questions can arise as to whether an equilibrium exists in the first place and, if it does, whether it is stable in the sense that, out of equilibrium, forces arise driving the model being analysed back to equilibrium. We do not examine these issues further on this course. 1 Block 2: Demand, supply and the market Demand and supply curves Activity SG2.1 Use the data in the following table to sketch for yourself a demand curve, a supply curve, and the whole market – where demand and supply interact. Be careful to put price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. What are the equilibrium price and quantity? Price of a Small Table (£) Quantity Demanded (thousands) Quantity Supplied (thousands) 0 90 0 10 75 15 20 60 30 30 45 45 40 30 60 50 15 75 60 0 90 (Note: Although these lines are straight, they are still called demand and supply curves). ► BVFD: read Maths box 3.1. Maths box 3.1 introduces a simple mathematical way of describing the demand and supply curves and finding equilibrium price and quantity. You need to be familiar with this algebraic approach where the constants in the supply and demand curves are given letters (here a, b, c, d) and where they are expressed as numbers, as in the following activity. Activity SG2.2 The direct demand function and direct supply function can be used to easily find the equilibrium quantity and price. Use the following curves to find the equilibrium price and quantity for noodles: QD= 30 – 3/4P QS= 5 + 1/2P Although people generally talk about quantity as a function of price, when it comes to drawing the graph, price is always drawn on the vertical axis, so it is easier to work with the inverse demand function, where price is expressed as a function of quantity demanded. For example: Inverse Demand: P = 20 – QD Inverse Supply: P = –6 + QS These equations are very useful for us to graph the demand and supply curves, because we can easily read the key characteristics of the curves straight off the relevant function. To graph the inverse demand function P = a/b – 1/b*QD (using the notation from Maths box 3.1), we can use the fact that the intercept on the price axis is a/b and the gradient is 1/b. Similarly, for the inverse supply function P = c/d + 1/dQS, the intercept is c/d and the gradient is 1/d. For example, if the inverse demand curve is P = 12 – 4QD, the demand curve touches the vertical axis at P = 12 and slopes downward with a slope of –4. 25 EC1002 Introduction to economics Activity SG2.3 Find the inverse demand and supply functions using the direct demand and supply functions in the table below and sketch them in a graph. Demand/Supply Function Demand Q = 30 – ¾*P Supply QS= 5 + ½*P Inverse Demand/Supply Function D Shifts in the demand and supply curves Economics is full of diagrams and curves. For every curve in every diagram you study you must understand what causes a movement along a curve and what shifts a curve. Start now with supply and demand curves. The first step with any curve is to note what is on the axes. With supply and demand curves it is price and quantity, with price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. This is awkward because it is not the usual way of using graphs, where we think of the variable on the vertical axis as a function of the variable on the horizontal axis, whereas we think of quantity as a function of price. The reason it is done this way is that this is how Alfred Marshall (1842–1924) introduced the supply and demand diagram. Marshall had good reason for drawing the axes as he did given the way he derived supply and demand from marginal cost and marginal utility (both concepts you will cover in this course). Movements along the demand curve represent the changes in the quantity demanded when the price of a good changes but the prices of other goods and income do not change. Shifts in the demand curve are due to changes in the prices of other goods as discussed briefly in BVFD section 3.4. We will explore this in mode detail in Block 4 (BVFD Chapter 5). 26 Block 2: Demand, supply and the market Activity SG2.4 For each event in the following table, identify whether this relates to demand or supply, in what direction the curve would shift, and the effect on price and quantity. If you draw a graph for each example, you will also see the movement along the other curve, resulting in the new equilibrium price and quantity. The first line has been completed for you. The market for sushi Event Which curve shifts? Supply or demand? Direction? Effect on price? Effect on quantity? Movement along the other curve – which direction? The price of salmon increases Supply Left Lower Demand, left Higher Sushi becomes more popular in Europe The price of similar alternatives rises Sushi sellers expect the price of sushi to rise in the future New evidence reveals sushi is not as healthy as people had thought New sushi machines make production more efficient Consumer and producer surplus ► BVFD: read section 3.8 and concept 3.2 on consumer and producer surplus. Imagine the following scenario: The current price for a two-litre carton of orange juice in my local grocery store is £1.50. That’s good news to me, because I was prepared to pay £2. The store manager is happy to see me loading some cartons into my trolley, because she knows the store would have been happy to sell them for just £1.10. I’m thinking: ‘This is great! I’m coming out 50p ahead on each carton!’ She’s thinking: ‘Fantastic! I’m coming out 40p ahead on each carton!’ So we are both enjoying a surplus. The equilibrium price is set by the marginal consumer and producer who were only willing to buy/sell for exactly £1.50. Consumers who would have been willing to pay more still just pay the equilibrium price and enjoy a surplus. Producers who would have been willing to sell it for less can still ask the equilibrium (market) price and also enjoy a surplus. The efficient market outcome occurs where consumer and producer surplus are maximised. We will come back to this later. 27 EC1002 Introduction to economics ► BVFD: read sections 3.9 and 3.10 as well as cases 3.3 and 3.4. These sections will further develop your understanding of demand, supply and equilibrium. You should read them carefully and try to think each point through. Can you think of another market where price floors or ceilings have been imposed? Activity SG2.5 Price floors and ceilings result in a loss of consumer and producer surplus, this is called a deadweight loss. Can you calculate how much consumer and producer surplus is lost due to the price ceiling in the diagram below? Has there also been a transfer of surplus between consumers and producers? Price £120 £100 Supply Curve £80 Free Market Equilibrium £60 £40 Excess demand Demand Curve £20 0 Price Ceiling 50 100 Quantity Figure 2.3: Loss of producer and consumer surplus due to a price ceiling. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. Overview Buyers and sellers come together in a market and exchange goods and services. Demand (from buyers) and supply (from sellers) are key concepts of economic analysis. Demand curves display the quantity that buyers wish to buy at each price and generally slope downwards – demand is higher when the price is lower. Supply curves display the quantity that sellers wish to sell at each price and generally slope upwards – sellers are prepared to sell more when the price is higher. The market clears (and equilibrium is achieved) at the point where the demand and supply curves intersect. Understanding what demand and supply curves represent and what makes them shift is the most fundamental lesson from this block. Price changes are represented by a movement along a curve, shifts in the curves indicate changes in other factors, such as the price of complements or substitutes or changes in consumers income (for demand curves) and changes in technology and input prices (for supply curves). Shifts in the demand or supply curves change the equilibrium price and quantity. Inverse demand and supply curves (where price is expressed as a function of quantity) can be useful for graphing the curves. The block also introduces consumer and producer surplus and the fact that price controls lead to a reduction in consumer and producer surplus, whereas free markets optimise consumer and producer surplus. You need to be able to calculate consumer and producer surplus and the loss involved due to price controls. 28 Block 2: Demand, supply and the market Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. From the diagram below, the loss in consumer surplus due to the price floor is: a. £50 b. £100 c. £150 d. £200. Price £50 Supply Curve Excess supply £40 Price Floor £30 Free Market Equilibrium £20 Demand Curve £10 0 10 20 30 Quantity Figure 2.4: Loss of consumer surplus due to a price floor. 2. Given the following inverse demand and supply curves: P = 8 – QD/2 P = 2 + QS and assuming that price is fixed below the equilibrium price at £5, the loss in producer surplus due to the price ceiling is: a. £3.50 b. £4.50 c. £8 d. £9. 3. The demand curve for good A is given by: Q AD = a – bPA + cPB Where PA is the price of good A, PB is the price of good B, and a, b, c are positive constants. The supply curve for good A is also linear and is upward sloping: a. Goods A and B are complements. b. Goods A and B are substitutes. 29 EC1002 Introduction to economics c. Goods A and B are unrelated in consumption. d. The demand curve for good A is upward sloping. 7. Suppose that the price of Porto wine was £20 per litre in 2010 and £25 per litre in 2011. Ingrid observes that Margaret’s consumption of wine rose from 1 litre per month in 2010 to 1.2 litres per month in 2011. Ingrid concludes that Margaret’s demand for Porto wine has to be upward sloping: a. Ingrid is wrong: given the above information Margaret’s demand for Porto wine has to be downward sloping. b. Ingrid is right: given the above information Margaret’s demand for Porto wine has to be upward sloping. c. Ingrid is wrong: the above information is not enough to conclude that Margaret’s demand for Porto is necessarily upward sloping. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. People consume chilli and tortillas. This means that an increase in the price of chilli would lead to a decrease in the consumption of tortillas. 2. Suppose that the price of port wine was £20 per litre in 2010 and £25 per litre in 2011. Ingrid observes that Margaret’s consumption of port wine rose from 1 litre per month in 2010 to 1.2 litres per month in 2011. Ingrid concludes that Margaret’s demand for port wine has to be upward sloping. 3. The market for theatre tickets has a downward sloping demand curve. Ragvir is the last person to buy a ticket and he pays exactly his willingness to pay. If this is true, there is no consumer surplus in the market. Long response question 1. Suppose that the inverse demand and supply schedules for rental apartments in the city of Auckland are as given by the following equations: Demand: P = 2700 – 0.12QD Supply: P = –300 + 0.12QS a. What is the market equilibrium rental price per month and the market equilibrium number of apartments demanded and supplied? b. If the local authority can enforce a rent-control law that sets the maximum monthly rent at $900, will there be a surplus or a shortage? Of how many units will this be? And how many units will actually be rented each month? c. Suppose that the government wishes to decrease the market equilibrium monthly rent to $900 by increasing the supply of housing. Assuming that demand remains unchanged, find the new equilibrium quantity and the new inverse supply curve. 30 Block 3: Elasticity Block 3: Elasticity Introduction The concept of elasticity is very important in microeconomics – here we devote a whole block to it! Elasticity has to do with responsiveness, for example: how much does the quantity demanded of a good respond to a change in the price of that good? For some goods, such as life-saving medicine, people’s demand will not fall much even if the price increases substantially, while for other goods, such as a particular chocolate bar, the demand will respond to price much more, since if the price of one chocolate bar goes up, people will generally be quite happy to purchase another one (or a different kind of snack) instead. This chapter uses many examples to make the concepts more intuitive, and also relies on graphs and simple equations. Make use of the exercises in this block and in the textbook to really master this concept and its applications. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • describe how elasticities measure the responsiveness of demand and supply • define and calculate price elasticity of demand • indicate the determinants of price elasticity • describe the relationship between demand elasticity and revenue • recognise the fallacy of composition • describe how cross-price elasticity relates to complements and substitutes • define and calculate income elasticity of demand • use income elasticity to identify inferior, normal and luxury goods • define and calculate elasticity of supply • describe how supply and demand elasticities affect tax incidence. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 4. Synopsis of this block This block will explore the reasons why demand for certain goods responds more or less to a change in price. Furthermore, we will also explore how demand for a good changes in response to a change in the price of another good, and also how it responds to a change in consumers’ income. As well as the elasticity of demand, we will also examine the elasticity of supply (i.e. how much producers’ supply decisions change in response to a change in price). The implications of elasticity for a firm’s total revenue, and for the effects of taxation shall also be examined. 31 EC1002 Introduction to economics Price elasticity of demand ►BVFD: Maths 4.1 and Maths 4.2. These sections are particularly important. You must know the definition of price elasticity of demand, cross-price elasticity of demand and income elasticity of demand. The formula for calculating price elasticity of demand (PED) is important and also quite intuitive: Price elasticity of demand = [% change in quantity] / [% change in price] As explained in Maths 4.1 this can be expressed using delta notation as: PED = ∆QD P ∆P QD where QD refers to quantity demanded and P to price. ∆ always means ‘change in’, such that ∆QD means ‘change in demanded’. If the quantity demanded changes a lot in response to a change in price, we say demand is responsive (or sensitive) to the price change, and the demand is elastic. If the price can change a lot without really affecting the quantity demanded, we say that demand is unresponsive (or insensitive) to the change in price and demand for that product is inelastic. • Demand is elastic if the elasticity is more negative than –1. • Demand is inelastic if the price elasticity lies between –1 and 0. This is represented in the sketch below: When PED=0 demand is said to be perfectly inelastic and when PED=–∞ we say demand is perfectly elastic. While economists often discuss the absolute value of the elasticity (so if this is between zero and 1, demand is said to be inelastic, and if it is greater than 1, demand is said to be elastic) we recommend you not to lose track of the sign of the elasticity. As we shall see below for other elasticities (cross-price elasticity, income elasticity), the sign has important implications. Nonetheless, you will often see positive numbers for ownprice demand elasticities – this is a shorthand and does not necessarily imply that the law of demand (i.e. that the demand curve for a good is downward sloping) has been violated. The Greek letter eta (ε) is often used to denote elasticity. For example, ε = 0 means that the price elasticity of demand is equal to zero and quantity demanded will not change at all in response to a change in price. Activity SG3.1 Consider your own buying habits. Rank the items below in terms of how responsive your demand for these goods is to a change in their price: • a nice pair of trousers • rice • bananas • medicine • holidays abroad. 32 Block 3: Elasticity ► BVFD: read Maths A4.1. There are various ways of calculating elasticity. Arc elasticity (Maths 4.1) is used to find the elasticity between two different points of a demand curve, in such a way that it is equal whether you analyse the change in price as an increase or a decrease. Point elasticity, on the other hand, describes the elasticity at a certain point on the demand curve. Maths A4.1 on point elasticity uses calculus, however, it also explains that the derivative of the direct demand function gives the slope of the direct demand function at a given point. If the function is linear, the slope is constant for the whole curve, and ∆Q corresponds to ∆P in the PED formula above (dropping the D superscript for simplicity). The slope of a curve is straightforward and something you can easily use without any knowledge of calculus. One thing to be careful of is whether you are using the direct or the inverse demand function (remember Block 2). For an inverse demand function, use the inverse of the slope. For a direct demand function, you can use the slope directly. That should be easy to remember! That means that for an indirect demand function, the point elasticity is: PED = 1/s * (P/Q), where s is the slope. For example: P = 20 – Q/2 is an indirect (or inverse) demand function. The slope of this is dP/dQ = –1/2. In this case, you would use PED = (1/–0.5) *(P/Q) = –2*(P/Q). On the other hand, Q = 40 – 2P is a direct demand function. The slope of this is dQ/dP = –2. In this case you would use PED = –2*(P/Q). (To check ∆Q that the slope of the direct demand function is equal ∆P note that if P = ∆Q -10 5, Q = 30, whereas if P = 10, Q = 20. Therefore ∆P = 5 = –2). If you want to express the elasticity as a positive number, you will need to use the absolute value (or just multiply the negative number by the minus one, which is the same thing). Activity SG3.2 Part A: Calculating an arc elasticity Given the following information, calculate the elasticity of demand for the following goods, expressing the elasticities as positive numbers. Initial Price and Quantity New Price and Quantity Good A Good B Good C Good D P0 = 4 P0 = 4 P0 = 5 P0 = 12 Q0 = 10 Q0 = 10 Q0 = 4 Q0 = 13 P1 = 5 P1 = 5 P1 = 2 P1 = 11 Q1 = 7 Q1 = 9 Q1 = 10 Q1 = 15 PED: value PED: category Part B: Calculating a point elasticity Given the following diagram, calculate the price elasticity of demand at X, Y and Z, expressing the elasticities as positive numbers, where PED = 1/s * (P/Q). 33 EC1002 Introduction to economics Price £20 At X, PED = At Y, PED = X £16 At Z, PED = Y £10 Z £5 8 20 30 40 Quantity Figure 3.1: Calculating point elasticities on a demand curve. ► BVFD: read sections 4.2 – 4.4 and cases 4.1 and 4.2. Activity SG3.3 The following table identifies some factors which act as determinants of demand elasticity. Fill in the fourth column, which has been left blank, with a concrete example. Factor Example Effect on demand elasticity Necessity People depend on this Demand is inelastic Substitutes There are many similar products available Demand is elastic Definition Good defined very narrowly More elastic (because there are more possible substitutes) Time-span Tastes change/more drastic adjustments become feasible Demand becomes more elastic The share of your budget Small items Demand is inelastic Good/Service Activity SG3.4 Sketch a perfectly inelastic demand curve and a perfectly elastic demand curve in separate diagrams. 34 Block 3: Elasticity Activity SG3.5 Total spending is the same as the firm’s revenue. Use the data below to decide, if you were a manager, whether or not to make the price change in the following cases (you can ignore costs for the purposes of this activity and just assume that an increase in revenue is a good thing and a decrease in revenue is bad). For each case, calculate the demand elasticity (using the arc method), decide whether or not to make the change, and then check your answer by calculating total revenue before and after the price change. a. Increasing the price from £6 to £7 will lead to a fall in sales from 10,000 to 8,000. b. Increasing the price from £8 to £10 will lead to a fall in sales from 15,000 to 12,500. c. Decreasing the price from £20 to £18 will lead to an increase in sales from 6,000 to 8,000. This activity emphasises the relationship between elasticity and total revenue. This is clearly explained in the textbook, but if you are not afraid of a bit of algebra we can derive a useful formula linking the two: TR = P * Q ∆TR ≈ Q∆P + P∆Q (This approximation depends on ∆P and ∆Q being small so that the product ∆P∆P is very small, or what is know as ‘second order small’) Dividing by ∆P: ∆TR ∆P but the second term is Q times PED so: ∆TR ∆P =Q+P ∆Q ∆P = Q (1 + PED) Remember that PED is negative and ∆P is positive for a price increase and negative for a price decrease. So, for example if demand is elastic, say –2, and price falls, then the sign of ∆TR is positive. If it is inelastic, say –0.3, and price falls, then the sign of ∆TR is negative. You may find it helpful to look at this in a more arithmetic way. Suppose that price starts at P and quantity at Q. Then there is a 1% increase in price so P changes to P (1 + 0.01). If the elasticity PED is –2 this implies that Q falls to Q(1 – 0.02). Revenue TR then changes from PQ to PQ(1 + 0.01)(1 − 0.02) = PQ(1 + 0.01 − 0.02 − 0.0002) The term 0.0002 is the product of 0.01 and –0.02 and is very small so the revenue after the price change is to a good approximation PQ(1 + 0.01 – 0.02) so the change in revenue is ΔTR≈TR(0.01−0.02) < 0 Another way of looking at this is that: ΔTR≈0.01PQ(1−2) = QΔP(1 + PED) This is negative because the price elasticity of demand –2 is less than –1. Another way of saying this is that the absolute value of the price elasticity of demand which is 2 is greater than 1. If the price elasticity of demand is less than 1 in absolute value then demand is said to be inelastic and revenue increases when the price increases. If the price elasticity of demand is greater than 1 in absolute value then demand is said to be elastic and revenue decreases when the price increases. 35 EC1002 Introduction to economics Cross-price elasticity of demand ► BVFD: read section 4.5. In Block 2, we discussed how a change in own-price leads to a movement along the demand curve, while a change in the price of a related good leads to a shift in the demand curve. An increase in the price of a substitute good will shift the demand curve to the right; an increase in the price of a complement will shift the demand curve to the left. Section 4.5 discusses the responsiveness of quantity demanded of a good (let’s call this good i) to a change in the price of a related good (which we can call good j) – this is known as cross-price elasticity of demand. The formulas for calculating this are the same as for own-price elasticities, except that you will use the original and new price of good j, and the original and new quantity of good i. For example, using delta notation the cross-price elasticity for good i with respect to the price of good j is: ∆Qi Pj ∆Pj Qi Unlike the case of a downward sloping demand curve where PED was always negative, the cross-price elasticity can be positive or negative depending on how the goods are related in consumption (whether they are substitutes or complements). The cross-price elasticity of demand is negative for complements and positive for substitutes. If the price of good i increases, people will demand less of good j if it is a complement to good i, and more of good j if it is a substitute for good i. What would be the value of the crossprice elasticity between two goods if they were completely unrelated? Activity SG3.6 Multiple choice question A Bordurian lawyer explains: ‘Smoking is a Bordurian tradition. If you had coffee, you had cigarettes; if you had cigarettes, you had coffee’. According to this statement, the cross-price elasticity of the demand for coffee with respect to the price of cigarettes in Borduria is: a. positive b. negative c. zero. Income elasticity of demand ► BVFD: read section 4.6 and case 4.4. Activity SG3.7 Classify the following goods, based on their (hypothetical) income elasticity: 36 Good Income elasticity Car 2.98 Food 0.5 Margarine –0.37 Vegetables 0.9 Public transportation –0.36 Books 1.44 Type of good Block 3: Elasticity Would you expect income elasticities for given goods to be broadly similar in different countries? For example, would you expect the income elasticity of demand for public transport to be similar in the USA and in Mali? Think about why or why not. The income elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a change in income and is measured by the percentage change in quantity demanded of good X divided by the percentage change in real consumers’ income. Using the delta notation and letting Q represent quantity of the good demanded and M represent real consumer income, income elasticity of demand (IED) is given by the formula: ∆Q M ∆M Q Price elasticity of supply ► BVFD: read sections 4.8. Activity SG3.8 For the following direct supply function QS = 5 + 2P calculate and interpret the PES when Q = 10 and P = 2.5. Activity SG3.9 Initially, the price of a tennis racket is £20. Demand is 30 and supply is 50. If the price falls by £5, the quantity demanded rises to 40, the quantity supplied rises to 40, and the quantity demanded of white cotton t-shirts rises from 70 to 100. Using the arc method, calculate the own-price demand elasticity and the elasticity of supply for tennis racquets; and the cross-price demand elasticity for white cotton t-shirts. Are white cotton t-shirts a complement or substitute to tennis racquets? Make sure that you also understand section 4.7 which brings together own-price, crossprice and income elasticities with reference to inflation. ► BVFD: Examine Table 4.11 – this provides a simple but helpful summary of the chapter. Incidence of a tax ► BVFD: read section 15.3 and Maths 15.1. We now jump forward to a later BVFD capture that examines the effect of a specific tax in a market and explores the incidence of the tax (i.e. who bears the burden of the tax). It is important to realise that a sales tax drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers (sometimes called the demand price) and the price received by producers (the supply price). In a simple supply and demand diagram in the absence of taxes these two prices are, of course, the same. The key point of this section is that the incidence of the tax is not related to the person who physically pays the money to the government. Rather, whichever party (consumers or producers) is less price sensitive (either in demand or supply) will bear the greater share of the burden of the tax.1 This is summed up by an expression, which we do not prove here, but which holds for small taxes: This is summed up in an expression which holds for small taxes, but which we do not prove here: 1 In words, the ratio of the change in the price the consumer pays (the demand price) to the change in the price that the producer receives (the supply price) is equal to the ratio of the price elasticity of supply to the price elasticity of demand. 37 EC1002 Introduction to economics PES ∆D = ∆S PED In words, the ratio of the change in the price the consumer pays (the demand price) to the change in the price that the producer receives (the supply price) is equal to the ratio of the price elasticity of supply to the price elasticity of demand. Suppose demand were perfectly inelastic, how would the burden of a sales tax be shared between consumers and producers? Another point to consider is why goods such as cigarettes and fuel are taxed so heavily. This isn’t only a question of improving health or reducing pollution – consider the PED of these goods and the implications for government tax revenues of taxing goods such as these. Activity SG3.10 Let’s put Maths box 15.1 into practice using a numerical example. If: QD = 30 – 4P QS = –6 + 8P t = 0.375 where t is a specific tax that has to be paid by suppliers. Calculate a. the equilibrium quantities with and without the tax b. the increase in the price paid by consumers and the fall in consumer surplus c. the fall in the price received by suppliers and the fall in producer surplus d. the tax revenue received by the government e. the deadweight loss of the tax. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the Sample questions. Overview This block describes the concept of elasticity, explores how to calculate elasticities and discusses the implications. Conceptually, elasticity has to do with responsiveness, usually how much demand or supply responds to a change in price or income. You need to know how to calculate arc and point elasticities. The type of elasticities you need to be familiar with are as follows: own-price demand elasticity (elastic if more negative than –1, unit elastic if –1, inelastic if between –1 and 0; though in practice these are often expressed as positive numbers using the absolute value), crossprice demand elasticity (generally positive for substitutes and negative for complements), income elasticity of demand (negative for inferior goods, larger than 1 for luxury goods) and supply elasticity (positive since the supply curve slopes upwards). Elasticity has implications for total spending on a product (which from the company’s perspective is simply revenue): If demand is elastic, a fall in price leads to an increase in revenue. It also has implications for tax incidence – the more price insensitive side of the market (be it buyers or sellers) will bear a greater burden of the tax. 38 Block 3: Elasticity Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions 1. Let the demand for jerk chicken be: QD = 200 – 6P + 2Y, where the price of jerk chicken is P and Y is consumer income. When the price of jerk chicken is £8, a rise in consumers’ income from £100 to £150 leads to: a. a fall in demand and an income elasticity of –0.14, jerk chicken is an inferior good b. a rise in demand and an income elasticity of 0.14, jerk chicken is a normal good and a necessity c. a rise in demand and an income elasticity of 7.08, jerk chicken is a luxury good d. a fall in demand and an income elasticity of –7.08, jerk chicken is an inferior good. 2. When price elasticity of demand is greater than unity (in absolute value), revenue will: a. increase with an increase in price b. decrease with a fall in price. c. decrease with an increase in price. d. remain unchanged with any change in price. 3. Market research about the demand faced by a particular firm producing good x reveals the following information: Own price elasticity: –2 Income elasticity: 1.5 Cross price elasticity with respect to y: 0.8 Cross price elasticity with respect to z: –3 Where x, y and z are goods and M is income. Therefore: a. Commodities x and z are complements while x and y are gross substitutes. b. Commodities x and z are complements and so are x and y. c. Commodities x and z are gross substitutes and so are x and y. d. Commodities x and z are gross substitutes but x and y are complements. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. If the cross-price elasticity of a good is negative, the income elasticity must also be negative. 2. If the demand for pizza drops whenever sushi becomes cheaper, pizza must be an inferior good. 39 EC1002 Introduction to economics 3. Football finals tickets are typically much more expensive than other football tickets, yet these events are typically sold out. Hence, football fans must have an inelastic demand for these tickets. Long response question 1. a.Define the different types of elasticity. What determines the price elasticity of demand for a certain good? Who can benefit from this information? b. Assume that the market demand for barley is given by: Q=1,900 – 4PB + 0.1M + 2PW Where Q is the quantity of barley demanded, PB is the price of barley, M is income (say per capita income of consumers) and PW is the price of wheat. The prices of wheat and barley are each 200 (say £s per tonne) and M is 1,000. The slopes for barley demand, wheat demand and income are –4, 2 and 0.1 respectively. Calculate the own price elasticity of demand, the income elasticity of demand and the cross-price elasticity of the demand for barley with respect to the price of wheat. c. Calculate and illustrate graphically the impact on welfare of a specific tax of 37.5p per unit to be paid by suppliers when QD = 30 – 4P and QS = –6 + 8P. How do the welfare implications change if the tax is paid by consumers instead of suppliers? 40 Block 4: Consumer choice Block 4: Consumer choice Introduction This block introduces another two fundamental concepts in microeconomics: indifference curves and the budget constraint. Indifference curves illustrate a consumer’s preferences, while the budget constraint shows what it is possible for them to consume, given a limited budget and the prices they face. Put together, these concepts are used to determine the consumer’s consumption decisions. In this way, we can see how the demand curves you learned about in Block 2 are derived. After studying the demand curve in Block 2, it is important to realise that this curve is the direct result of the assumptions of rationality and individual decision making as discussed in Block 1. This block, on consumer choice, draws on the idea of opportunity cost as well as individual preferences to derive the demand curve. You will need a good understanding of the intuition behind the models in this block. It is important that you gain a good grasp of them, because we use an equivalent set of concepts in analysing how firms make their production decisions (Block 5), and they are also used to determine household’s labour supply (Block 9). As well as this, you will also need to practise drawing the graphs in this chapter, since they will help to understand the concepts, and since you may need to be able to reproduce them for your exam. In particular, practise drawing the income and substitution effects for normal and inferior goods, since many of the key concepts are summarised in these graphs. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • define the relationship between utility and tastes for a consumer • describe the concept of diminishing marginal utility • describe the concept of diminishing marginal rate of substitution and calculate the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) • represent tastes as indifference curves • derive a budget line • explain how indifference curves and budget constraints explain consumer choice • describe how changes in consumer income affect quantity demanded • describe how a price change affects quantity demanded • define income and substitution effects • show how the market demand curve relates to the demand curves of individual consumers. Note, that cash versus transfers in kind are not covered by the subject guide and are not examinable. In case of interest this it covered in Chapter 5.6 of BVFD. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 5 (except 5.6) including the appendix. 41 EC1002 Introduction to economics Synopsis of this block The chapter starts by introducing the concept of utility, and the assumptions that are commonly made by economists about utility. It then explains indifference curves and the budget constraint and shows how these are combined to determine the consumer’s choices. The impact of changes in the consumer’s income and changes in price are examined in detail, including the decomposition of the effects of price changes into income and substitution effects. The chapter also demonstrates how these ideas are used to derive the individual demand curve, and then the market demand curve. The relationship to elasticity, particularly cross-price elasticity, is also discussed. Consumer choice and demand decisions ►BVFD: read section 5.1 and concepts 5.1 and 5.2. Utility The concept of ‘utility’ was introduced by Jeremy Bentham, in his 1789 book Principles of morals and legislation. He defined it as follows: ‘By utility is meant that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness, (all this in the present case comes to the same thing) or (what comes again to the same thing) to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered.’ The philosophy of ‘utilitarianism’ (the ‘greatest happiness principle’) was invented by Bentham and has been very influential. The textbook defines utility much more simply as ‘the satisfaction consumers get from consuming goods’ (p.74). In the 19th century, economists believed that utility levels could be measured, and used a unit of measurement called ‘utils’. Nowadays, economists assume that utility is not measurable in this way, but is still a useful concept that underlies much of microeconomics. Marginal utility As discussed in Block 1, consumers and firms make decisions at the margin. This idea is very important in relation to utility. The marginal utility of a good or service is the extra utility a person gains from consuming one more unit of that good or service. Activity SG4.1 Linking the shape of the indifference curves to the assumptions regarding consumer tastes. The various assumptions that lie behind indifference curves are reflected in certain aspects of the shape of the curve. Match the assumption to the characteristic of the curve and explain why. 42 Diminishing marginal rate of substitution Lines never cross Consumers prefer more to less (non-satiation) Any bundle is on some indifference curve Completeness Indifference curves convex to the origin (ICs look like ‘smiles’ when seen from the origin) Transitivity Downward sloping Block 4: Consumer choice The slope of the indifference curve is the marginal rate of substitution The marginal rate of substitution (MRS) between two goods, as you know from the definition on p.76, measures the quantity of a good the consumer must sacrifice to increase the quantity of the other good by one unit without changing total utility. On pXX, in the paragraph discussing how the slope of a typical indifference curve gets steadily flatter as we move to the right, there is an important gem of information: ‘The marginal rate of substitution … is simply the slope of the indifference curve’. On the graph below, the tangent T shows the slope of the indifference curve and the MRS at point b.1 Consider the indifference curve depicted in Figure 4.1 showing all combinations of Clothing and Food that give the consumer the same level of utility. The MRS is the absolute value of the ratio of the change in clothing to the change in food. Since these two changes always have opposite signs, the MRS (slope of an indifference curve) is obtained by multiplying ΔC/ΔF by –1. Some textbooks define the MRS as the slope of the indifference curve, that is as a negative quantity, others as the ‘absolute value’ of the slope (i.e. as a positive quantity). This is simply a matter of convention and it doesn’t matter which convention is followed, as long as one is consistent. 1 35 a Clothing 30 25 20 b 15 c 10 e f T 5 0 d 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 Food Figure 4.1: The marginal rate of substitution is the slope of the indifference curve. Movement Change in clothing Change in food Marginal rate of substitution From a to b –12 5 (–12/5)*–1 = 2.4 From b to c –5 5 (–5/5)*–1 = 1.0 From c to d –3 5 (–3/5)*–1 = 0.6 From d to e –2 5 (–2/5) * –1 = 0.4 From e to f –1 5 (–1/5) * –1 = 0.2 Table 4.1 You should remember from Block 3 that Δ (delta) means change. Examining the movement from a to b and b to c etc. gives us a good approximation of the slope of various sections of the curve. An even more accurate way is to examine the change in utility due to a one unit change in either of the goods: this gives us the marginal utility of each good at a point on the curve. In fact, the MRS is given by –MUF/MUC, (i.e. the marginal utility of food at a certain point on the indifference curve, divided by the marginal utility of clothing at that point, multiplied by –1). We will come back to this again at the end of the block (as it is covered in more detail in Maths A5.1). 43 EC1002 Introduction to economics Figure 5.5 of BVFD also helps to illustrate this idea, showing indifference curves for people with different tastes. The glutton is more willing to substitute films for food than the weight-watching film buff and has a higher MRS. Drawing a tangent to any part of their indifference curves shows that the slope of the gluttons indifference curve is steeper – reflecting his higher MRS between meals and films. The slope of a typical indifference curve gets steadily flatter as we move to the right, reflecting a diminishing marginal rate of substitution. Clothing For example: a A b B Food Figure 4.2: Changes in the slope of an indifference curve reflect a diminishing marginal rate of substitution. The slope of the tangent A shows the MRS of food for clothing at point a. Similarly, the slope of the tangent B shows the MRS at point b. We can see that the slope flattens as we move from a to b, reflecting a diminishing MRS. At point a, the person has quite a lot of clothing and is willing to substitute a fair bit of this for a certain amount of food. At point b, the person has much less clothing but quite a lot of food and is only willing to substitute a very small amount of clothing to gain the extra amount of food. Going back to Table 4.1, you can also see the diminishing MRS, as the amount of clothing the person is willing to substitute for 5 additional units of food continues to fall. Budget constraint Activity SG4.2 The slope depends only on the relative prices of the two goods. Draw budget constraints for the following three price combinations, assuming a total income of £120. a. PX=£12,PY=£20 b. PX=£10,PY=£20 c. PX=£12,PY=£15 What is the interpretation of the slope of the budget constraint? It represents the rate at which the consumer can substitute good X for good Y in the market, or the opportunity cost of X in terms of Y. To see this, suppose the consumer wishes to consume a little more X, ∆X. This will cost her ∆XPX. Assuming she was spending all her income on X and Y (on her budget line) then she will have to reduce her expenditure on Y by the same amount. So ∆XPX=–∆YPY , (i.e. the slope ∆Y/∆X=–PX/PY). 44 Block 4: Consumer choice ► BVFD: read Maths 5.1. You should be familiar with the general form of the budget constraint used in this section, (i.e. where Px is the price of good X, Py the price of good Y, x the quantity of good X, y the quantity of good Y and M the money income available to the consumer). Note that the first term on the left-hand side of this equation is the consumer’s expenditure on good X and the second term is expenditure on good Y. Since we assume that the consumer spends all her income on these two goods, the amount spent on the two goods sums up to M which is her income. One important point from this Maths box is that the slope of the budget constraint is given by –Px/Py i.e. the price ratio. The figure in this Maths box shows how you can represent a general case, where you don’t have specific quantities and prices. The intercepts will then be M/PY and M/PX respectively. This is likely to be how you will draw a budget constraint most often. Utility maximisation and choice Indifference curves and the budget constraint together indicate the choice a consumer will make to maximise their satisfaction. This can be represented by the following diagram: Step 1 Preferences (What the individual wants to do) Step 2 Budget Constraint (What the individual can do) Step 3 Decision (Taking constraints into account, the individual attempts to reach the highest level of satisfaction) Figure 4.3: Consumer choice and the decision rule. Decision rule The point which maximises utility is the point at which the consumer reaches the highest indifference curve that the budget constraint allows. For the ‘standard’ indifference curves we have been looking at, this decision rule says that the consumer should choose the consumption bundle where the slope of the budget line and the slope of the indifference curve coincide. In other words, it is the point at which the indifference curve is tangent to the budget constraint. ► B VFD: read appendix A1 of Chapter 5 of, which applies whether or not utility can actually be measured. We can describe the consumer’s optimal decision using equations as follows: At the chosen bundle, the marginal rate of substitution between the two goods must equal their relative price, i.e. MRS =–MUx/MUy =–Px/ Py. Rearranging this gives MUX/PX= MUY/PY . 45 EC1002 Introduction to economics Good Y We can also describe their decision graphically, as follows: The consumer choses the bundle where the indifference curve is tangent to their budget constraint. The slope of the indifference curve (MRS = –MUx/MUy) and the slope of the budget constraint (–Px/Py)must be equal. The tangency thus implies –MUx/MUy = –Px/Py. Rearranging this gives MUX/PX=MUY/PY. M/Py b u0 M/Px Good X Figure 4.4: A budget constraint and an indifference curve. MUX/PX=MUY/PY has the intuitive interpretation that the marginal utility derived from the last pound spent on X must be equal to the marginal utility of the last pound spent on Y. Otherwise the consumer would adjust their consumption pattern and increase their utility. Imagine that MUX/PX > MUY/PY. This implies that the consumer derives more utility from the last pound spent on good X than the last pound spent on good Y. In this case, by consuming one pound more of good X and one pound less of good Y, they can increase their utility level without spending any more money. The consumer should continue to adjust their spending in this way until MUX/PX=MUY/PY. It is important to understand the intuitive explanation of the consumer’s decision, as well as being familiar with the relevant equations and graphs. ► BVFD: read section 5.2 and case 5.1 Activity SG4.3 Draw budget constraints and possible indifference curves for the following scenario: Susan buys cabbages and carrots. Cabbages cost £1 per kilo and carrots cost £0.80 per kilo. Her income falls from £20 to £16. Carrots are a normal good, but cabbages are an inferior good. ► BVFD: read section 5.3 and case 5.2. Activity SG4.4 Figure 5.13 shows the effect of an increase in the price of meals in a diagram with meals and films on the axes. Subsequent diagrams explore the effect on consumer choice. Draw a diagram to check your understanding of the following two cases: a. a fall in the price of meals b. an increase in the price of films. 46 Block 4: Consumer choice Income and price changes Substitution and income effects Decomposing the effects of a price change into income and substitution effects is an important piece of economic analysis with many real world applications. Case 5.1 shows one such application; others relate to the effects of changes in wages on labour supply and changes in interest rates on savings decisions. Remember: • The substitution effect is always negative. • The income effect is negative for normal goods and positive for inferior goods. • For normal goods, the income and substitution effects reinforce each other. • For inferior goods, the income and substitution effects work in opposite directions. • For inferior goods, if the income effect dominates the substitution effect, the good is called a Giffen good (in practice, these are very rare). Activity SG4.5 For a choice between Good X and Good Y, analyse the following cases, clearly indicating the income and substitution effects in each case. a. The price of good X rises and it is a normal good. b. The price of good X rises and it is an inferior good. c. The price of good X falls and it is a normal good d. The price of good X falls and it is an inferior good. Advice in tackling this activity: You will find Figures 5.16, 5.17 and 5.18 helpful for this activity, and you might want to repeat it a few times on a separate sheet of paper until you are really comfortable with these concepts. The following order is generally best: STEP 1.Draw the original budget line and indifference curve. STEP 2.Draw the new budget line. STEP 3.Draw the hypothetical budget line parallel to the new budget line and tangent to the original indifference curve. This gives you the substitution effect. STEP 4.Draw the new indifference curve (where you place this depends on what type of good it is). This gives you the income effect. 47 EC1002 Introduction to economics Deriving demand: ‘The individual demand curve’ In Block 2 we introduced demand and supply and learned about the demand curve. Now we are able to derive the individual demand curve from the choices of consumers. Activity SG4.6 Derive the individual demand curve from the information in figure A and sketch it in B. Can you now explain why the demand curve is downward sloping? Sunglasses A (Price per sandwich = p1) (Price per sandwich = p2) e1 e2 e3 e4 Price-consumption curve (Price per sandwich = p3) (Price per sandwich = p4) x1 x2 x3 x4 0 Sandwiches Price per Sandwich B Sandwiches 0 Figure 4.5: Deriving the individual demand curve. ► BVFD: read the second part of the appendix: deriving demand curves. This explains why, for normal goods, a fall in price leads to an increase in quantity demanded, due to both substitution and income effects. Demand curves and consumer surplus We have now shown the theoretical underpinnings of a downward sloping demand curve. In particular, we have gone beyond general statements such as ‘at lower prices existing consumers want to purchase more and new consumers enter the market’ and shown that at each point on the demand curve consumers are maximising their utility by equating their P MU MRS ( MU ) with the relative price ( P ) where x is the good on the horizontal axis and y the good on the vertical axis. This enables us to give further intuition to the price at any given quantity and to the whole demand curve. 48 x x y y Block 4: Consumer choice To do this, we can put some numbers on a given utility maximising point corresponding to a set of prices for x and y and a given income. For example, let Px = £4, Py = £2 and income = 40. This is shown on the diagram below. This diagram shows the consumer’s utility maximising combination of x and y (x1, y1) at A in the upper panel and the demand for x at Px = £4, Py = £2, M = £40 in the lower panel. How much is an extra unit of x worth to the consumer at A’? At A, due to the tangency, MRS = –2. This means our consumer would give up 2 units of y in order to have another unit of x – that is the meaning of MRS = –2; one unit of x has the same value to her as 2 units of y. Since y costs £2 per unit, two units of y are worth £4, an extra unit of x must also be worth £4 as an extra unit of x is worth the same as two units of y at A. Another way of saying this is that at A and A’ the consumer’s willingness to pay for another unit of x is £4. So price can be interpreted as the willingness to pay for an extra unit of the good, given income and prices of other goods. Similarly, the demand curve can be interpreted as a willingness to pay curve (its downward slope implying that the more x the consumer has, the lower her willingness to pay for an extra unit). Although we do not do the mathematics here, you can see intuitively that because price at a given x represents the willingness to pay for a marginal unit of x, the area under the demand curve up to that level of x shows the total willingness to pay for that amount (the sum of the willingness to pay for each separate unit). This also makes it easier to see that the consumer surplus (a concept introduced in Block 2) at any given price and quantity is the difference between the total willingness to pay for that amount minus what is actually paid – the prevailing price times the quantity. y 20 y1 At A, MRS = −Px/Py = −4/2 = −2 A Indifference curve x1 10 x Px 4 A/ Demand curve for x x1 x Figure 4.6: Willingness to pay and consumer surplus. 49 EC1002 Introduction to economics Deriving demand: ‘The market demand curve’ ► BVFD: read section 5.4. The market demand curve is the horizontal addition of the demand curves of all the individuals in that market. In the following activity we assume that there are only three consumers, but the method can be applied to much larger numbers; in such cases kinks in the market demand curve would tend to be smoothed out. Activity SG4.7 Consumer 3 12 12 12 12 8 8 8 8 4 4 4 4 0 7 2 4 6 5 10 Figure 4.7: Deriving the market demand curve. Complements and substitutes ► BVFD: read section 5.5 of and the part of 5.3 which addresses cross-price elasticities of demand. Section 5.5 on complements and substitutes introduces the fact that goods are not always substitutes for each other, but may in fact be complements. This means that if the demand for a good rises, then the demand for other complementary goods will rise as well. You will remember from Block 3 that cross-price elasticities are negative when two goods are complements and positive when two goods are substitutes. The section on cross-price elasticities (in section 5.3) details three factors which impact on income and substitution effects and can make the cross-price elasticity for good Y either positive or negative (responding to a change in the price of good X). These are: whether the two goods are good substitutes for each other; the income elasticity of demand of good Y; and good Y’s share of the consumer’s total budget. Section 5.5 also shows that not all indifference curves are convex to the origin as in Figures 5.2 and 5.3 of BVFD. How well the two goods can be substituted for each other is reflected in the shape of the indifference curves as follows: 50 PRICE Consumer 2 PRICE Consumer 1 PRICE PRICE Complete the fourth graph, showing the market demand curve. Why might the three consumers have different demand curves? • Figure 5.20, left hand side depicts perfect substitutes. This is where indifference curves are straight lines – full substitution from one to the other if the price of one good falls below the price of the other good. • Figure 5.20, right hand side depicts perfect complements. This is where ndifference curves are perpendicular lines – no substitution effect of a price change, the consumer will consume more (or less) of both in the same proportion. Market demand Block 4: Consumer choice • Figure 5.18 depicts good substitutes – indifference curves are quite flat – large substitution effect of a price change. • Figure 5.17 depicts poor substitutes – indifference curves are very curved – small substitution effect of a price change. Activity SG4.8 Draw the indifference curves for perfect complements together with a budget line. Now draw a new budget line for a change in the price of one of the goods. Indicate the income and substitution effects (if any) of the price change. Activity SG4.9 Barbara likes peanut butter and jam together on her sandwiches. However, Barbara is very particular about the proportions of peanut butter and jam. Specifically, Barbara likes 2 scoops of jam with each scoop of peanut butter. The cost of ‘scoops’ of peanut butter and jam are 50p and 20p, respectively. Barbara has £9 each week to spend on peanut butter and jam. (You can assume that Barbara’s mother provides the bread for the sandwiches.) If Barbara is maximising her utility subject to her budget constraint, how many scoops of peanut butter and jam should she buy? Activity SG4.10 Suppose that a consumer considers coffee and tea to be perfect substitutes, but he requires two cups of tea to give up one cup of coffee. This consumer’s budget constraint can be written as 3C + T = 10. What is this consumer’s optimal consumption bundle? ► BVFD: read appendix A2 and Maths A5.1. The section of the appendix introduces utility functions. As is written, although no one really knows anyone’s utility function for any good, expressing utility numerically through a utility function can be very useful. The maths box shows how marginal utility can be found using the delta notation or calculus. If you are familiar with calculus, you may find this makes marginal analysis much easier. However, it is also possible to use the delta notation to find marginal utility, or else this will be given to you, as per the activity below. Activity SG4.11 Calculate the optimal quantity of each of two goods (x and y) and the consumer’s total utility given px = 1, py = 2, M = 80, and U(x,y) = xy, where MUx = y and MUy = x. How would you represent this graphically? ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions in Chapter 5. Overview This block started by introducing utility and indifference curves, as well as the budget constraint. Indifference curves represent consumer tastes, while the budget constraint shows the possibilities open to the consumer, given their limited budget. Putting these together, we learned the decision rule that determines consumer choice, under the assumption that consumers maximise utility. In particular, we saw that consumers will chose the bundle of goods such that MUX/PX = MUY/PY. Expressed graphically, this means that the highest reachable indifference curve is tangent to the budget constraint. We then explored how their choices are affected by changes in income and prices, looking in particular at income and substitution effects of a price change. This helped us identify normal 51 EC1002 Introduction to economics and inferior (and Giffen) goods. We also further examined complements and substitutes. Understanding how consumers make choices lets us see what lies behind the – individual and market – demand curves. Finally, the analysis of budget constraints and indifference curves also made it possible to evaluate the relative benefits of cash transfers versus transfers in kind. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. Judith spends all her money buying wine and cheese and wants to maximise her utility from consuming these two goods. The marginal utility of the last bottle of wine is 60, and the marginal utility of the last block of cheese is 30. The price of wine is £3, and the price of cheese is £2. Judith: a. is buying wine and cheese in the utility-maximising amounts b. should buy more wine and less cheese c. should buy more cheese and less wine d. is spending too much money on wine and cheese. 2. Harry considers coffee and tea to be perfect substitutes, but he requires two cups of tea to give up one cup of coffee. His budget constraint can be written as 3C + T = 10. How should Harry pick his optimal consumption bundle? a. Harry should only consume tea and demand T=10. b. Harry should only consume coffee and demand C = 10 3 c. Harry should pick a bundle at the tangency between his indifference curve and his budget constraint, where his MRS equals the price ratio. d. Harry can consume any affordable bundle containing both tea and coffee. 3. The price of an inferior good goes down. As a result consumption: a. increases as income and substitution effects enhance each other b. decreases as income and substitution effects enhance each other c. increases if the good is not Giffen d. is unchanged as income and substitution effects offset each other. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. If Daniel’s rent went up by 10% this year, but his income increased by 15% he cannot be worse off than last year. 2. Carla’s income increased by 20% last year and she bought 10% more audiobooks. This means that audiobooks are inferior goods for Carla. 3. Mark likes jeans and cowboy boots. He experiences diminishing marginal utility over these two goods. He is indifferent between 52 Block 4: Consumer choice a bundle with three pairs of jeans and two pairs of cowboy boots (bundle A) and a bundle with two pairs of jeans and four pairs of cowboy boots (bundle B). Given this information we infer that he would prefer a bundle with three pairs of jeans and three pairs of cowboy boots. Long response questions 1. Ivan earns £80 per week and needs to decide how many cans of Coke and sandwiches to buy. Each sandwich costs £4 and every can of Coke costs £2. His utility function is U(s,c) = sc, where s stands for sandwich and c for can of Coke. a. Find an equation for Ivan’s budget constraint and show the budget constraint in a diagram. b. Calculate the optimal weekly amounts of sandwiches and cans of Coke for Ivan and show the optimal bundle on a graph. c. Ivan has worked hard this year and his boss decides to give him a raise. He now earns £100 per week. Show the increase in income on a graph and discuss how it affects his demand for sandwiches and Coke. d. Explain what would happen if the price of sandwiches went up by £5 and income remained at £100 per week. Show Ivan’s new budget line on a graph. Would Ivan still demand the same amounts of sandwiches and cans of Coke? e. Explain the difference between normal, inferior, and Giffen goods and what sign the income and substitution effects are in each of these cases. Are sandwiches a normal good in this case? 2. Susan buys bagels and falafels. The price of a falafel is £1 and the price of a bagel is £3. Susan has £12 to spend on bagels and falafels. a. Draw Susan’s budget constraint and a possible indifference curve. Explain the assumptions behind the shape of the indifference curve you have drawn. b. If the price of falafels falls to £0.80 each, how will this affect her purchases? Answer in words and graphically, clearly indicating income and substitution effects of the price change. c. If Susan only enjoys bagels and falafels when she has two falafels for every bagel that she eats, draw her indifference curves. How many bagels and falafels should she buy to maximise her utility? Assume Susan has £12, one falafel costs £0.80 and bagels cost £3 each. d. Susan’s friend Declan grows 100 potatoes each year and all of his income comes from selling them. He spends all of his income each year consuming potatoes and other goods. For Declan, potatoes are a Giffen good, in that for a given income his consumption of potatoes will rise when their price rises. The price of potatoes falls, and he consumes more potatoes. Taking into account the fact that his income actually comes from selling potatoes, explain how the last statement can be consistent with those that precede it. 53 EC1002 Introduction to economics Food for thought – Box 1: Why do consumers experience regret? We’ve spent quite some time thinking about how consumers optimise their decisions based on their preferences, given prices and their income. Classical consumer theory assumes consumers are rational decision makers who know their own preferences and that these preferences are stable, at least for the period of analysis. And yet, if consumers are always optimising, then their decisions should always be the best possible and so they should never regret their choices! But how realistic is this? There are areas of life or circumstances in which many of us make poor choices and then come to regret our decisions. For example, consuming food that is high in fat or sugar and then regretting not going for healthier options; or overspending in the present rather than saving for the future; or not exercising enough (despite having a gym membership!). How can we square consumer regret with consumer theory? Behavioural economics draws insights from the psychology literature to refine our understanding of consumer decision making. In fact, several Nobel prizes in Economics have been awarded in this area for the study of different aspects of behaviour and an investigation into rationality (Daniel Kahneman in 2002 and Richard Thaler in 2017). We now understand that decision makers are subject to a range of cognitive biases, which can lead to feelings of regret, especially in areas where we struggle with self-control. For example, we may be biased by our current emotions and fail to anticipate correctly how we will feel in the future about our current choices. We might also be influenced by how choices are presented to us (or ‘framed’), realising this only later. One way to conceptualise what is going on is that the utility function consumers perceive at the time of decision making (known as decision utility) is different from the utility that is actually experienced when the consumption bundle is actually consumed (experienced utility). To read more about decision and experience utility, visit Decision Utility, The Decision Lab. 54 Block 5: The firm Block 5: The firm Introduction The two most important concepts in microeconomics are demand and supply. In the previous block, we saw what lies behind the demand curve and how this is driven by consumer preferences and the constraints imposed by their budgets. In this and the following blocks, we will explore what lies behind the supply curve. Basically, supply depends on the technology available to firms, the cost of inputs, and the market structure the firm operates in (e.g. the number of other sellers, which affects price and revenue at each level of output). This block provides an introduction to the analysis of the firm. We assume that firms attempt to maximise profit and profit is equal to revenue minus cost. A large part of the block analyses firm costs – from total cost to fixed and variable costs, average costs as well as marginal costs, and the relationships between all of these. The early material in Chapter 7 of BVFD is quite straightforward. Although you will need to be familiar with this to have a context for the more detailed analysis, you should concentrate your attention on the material from Chapter 8 (especially the appendix). Numerical examples are provided in the block to help you calculate the firm’s optimal level of output. You should also practise representing these concepts graphically. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • distinguish between economic and accounting definitions of cost • describe the relationship between revenue, cost and profit • describe the production function • identify the point of diminishing marginal returns • demonstrate how the choice of production technique depends on input price • use isoquants and isocost curves to derive the firm’s total cost curve • calculate marginal cost and marginal revenue • find the profit maximising level of output, given the firm’s demand curve and total cost curve. • identify fixed and variable factors in the short run • analyse total, average and marginal cost, in the short run and long run • draw the relevant cost curves and explain why they have certain shapes • define returns to scale and their relation to average cost curves • describe how a firm choses output, in the short run and the long run • describe the relationship between short-run cost and long-run cost. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 6; Chapter 7 sections 7.1, 7.2 and appendix. 55 EC1002 Introduction to economics Synopsis of this block This block introduces the firm including types of firms, the concept of economic costs and how this differs from accounting cost, and the arguments in favour of and against the frequently made assumption that firms intend to maximise their profits. It examines why firms chose a certain level of output by first introducing the production function, as well as isoquants and isocost curves and uses them to derive the firm’s total cost curve. It also shows how the demand curve facing the firm can be used to derive the firm’s total revenue curve. Profit is equal to revenue minus cost, thus through understanding the firm’s revenue and costs, we can find the profit function. The concepts of marginal cost and marginal revenue are introduced, to show that provided that it is profitable for the firm to operate at all, it will choose its level of production such that marginal cost and marginal revenue are equal. Production, costs and the output decision in the short run (where at least one factor of production is fixed) is discussed, followed by a discussion of the long run (where all inputs are variable). There is also a more detailed discussion of returns to scale. The block concludes by discussing the relationship between short-run and long-run costs. ► BVFD: read section 7.1–7.3, including concept 7.1. Introduction to the firm Section 7.1 outlines the most common forms of business enterprises: sole traders, partnerships and limited liability companies. Section 7.2 discusses a firm’s accounts. If you have taken any accounting courses, you will be familiar with these concepts, though here they are approached from an economic perspective. In particular, the discussion of accounting profit versus economic profit and the concepts of zero economic profit and supernormal profit are especially important to understand. Section 7.3 introduces the principal agent problem. These sections provide useful background knowledge to the economic analysis of the firm. Activity SG5.1 What is the economic cost of studying for an undergraduate degree? ► BVFD: read section 7.4. After this point, the subject guide moves on to BVFD Chapter 8, returning to Chapter 7 later in the block. The firm’s supply decision This discusses the fundamental idea that firms maximise profits, and profits are the difference between total revenue (the amount of money the firm gets by selling what it produces) and the total economic cost of production. The notation is π for profits, TR for total revenue and TC for total cost. Total revenue TR = PQ where P is the price of the good and Q is the quantity sold. For simplicity, we assume that a firm produces only one type of good. Profits, total revenue and total cost all depend on output Q, so we can write π(Q) = TR(Q) − TC(Q) Thus, the firm’s problem is to maximise profits as a function of Q. Note, that BVFD Chapter 7.5 starts with a discussion in which firms can only producer integer quantities of output and works with tables of 56 Block 5: The firm marginal revenue and marginal cost. However, it is essential that you study the calculus treatment (Maths A7.1 and Maths A7.2). You should also supplement this by reading an introductory maths textbook on calculus that covers maximisation and minimisation for functions of a single variable. In particular this is discussed in Chapter 3 of the subject guide for Mathematics 1 (MA105a), which includes a discussion of marginals and profit maximisation, and in Chapter 8 of the textbook for MA105a (Anthony, M. and N. Biggs, Mathematics for economics and finance, Cambridge University Press, 1996). If you have already studied this material go back and review it now; if you have not yet studied this material, make sure that you study it as part of your revision for this course. It is important to understand the difference between a local and a global maximum. The mathematical treatment focuses largely on first- and second-order conditions for a local maximum. Economists are interested in finding a global maximum. We do this by looking at the relative sizes of marginal revenue and marginal cost. The diagrams and functions you see in BVFD Chapter 7 all have the property that marginal revenue is at first greater than marginal cost, so profits are increasing in Q. Then there is a value of Q at which marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. Above this value of Q marginal revenue is less than marginal cost, so profits are decreasing in Q. This ensures that the level of Q at which marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost gives a profit maximum. Section 7.4 of the textbook looks at these three elements quite briefly, but using some of the material in Chapter 8 and some additional graphs, we will explore them in somewhat greater detail. At the end of the paragraph on cost minimisation is a footnote pointing to the appendix of Chapter 7. We will work through the appendix in detail, as this will allow us to derive the firm’s total cost function. However, first we need an introduction to the production function – this can be found in sections 8.1 and 8.2. After working through some parts of Chapter 8 relating to cost, we will come back to Chapter 7 to examine revenue and then use these two concepts (cost and revenue) to find the firm’s profit function. The production function ► BVFD: read section 8.1. Logically, the fundamental concept in producer theory is the production function, which gives output as a function of inputs. To make things simple we assume at this level that there are two inputs, capital and labour. This course treats in detail the short run in which capital is fixed, and the only decision is how much labour to use. In the long run, both labour and capital are variable and the theory needed to analyse this properly is more complicated than that needed for the short run. It is outlined in the appendix to Chapter 8, which you should read. However, detailed discussion of production functions and their relationship to cost functions is deferred until the EC2066 Microeconomics course. We begin with production. The hill-shaped structure depicted in Figure 5.1 is the production set, the set of technically feasible combinations of output Q, measured vertically, and inputs, K and L on the horizontal plane. It includes all the area on the surface and in the interior of the hill. A technically efficient production decision will be a point ‘on’ the hill, while points ‘in’ the hill represent technically inefficient production decisions in the sense that the input combination corresponding to the point is 57 EC1002 Introduction to economics Output capable of producing more output. The production function Q= f(K,L) is only the surface (and not the interior) of the hill, and denotes the set of technologically efficient points of the production set (i.e. for a given combination of inputs, K and L, output Q is the maximum feasible output). The contours of the hill (i.e. the cross-sections of the ‘hill’) are comparable to the isoquants in the appendix of Chapter 8, showing combinations of capital and labour that generate a given output. Note that the production function as used by economists is a very simplified summary of the relationship between inputs and output; an engineer setting up a production process for mobile phones or motor cars (to use two examples from the textbook) would have a much more detailed blueprint of the production process. Q=f (K,L) K L Figure 5.1: The production set. The production and cost functions take technology as given. Many firms of course are developing new technologies, either new products or new ways of making products. There is some discussion of this in BVFD Chapter 18 on economic growth, but a proper analysis of the microeconomic issues requires the tools developed in EC3099 Industrial economics. ► BVFD: read section 8.2. The total output curve (also known as the total product curve), shown in Figure 8.2 of the textbook, is a reduced form of the production function for the short-run, when only one input is allowed to vary and the other is held fixed. We can find this curve by ‘slicing’ the hill in Figure 5.1 above vertically at a particular level of capital K0. The reduced production function Q = ƒ (L, K0), is thus a vertical section of the hill. Activity SG5.2 Describe how the phrase ‘too many cooks spoil the broth’ can demonstrate the law of diminishing returns. 58 Block 5: The firm ► BVFD: read case 8.1 and Maths 8.1. Activity SG5.3 Define the following terms and give a formula for b. and c. a. total product b. average product c. marginal product. Activity SG5.4 Complete the following table: Quantity of Labour (L) Total Product (TP) 1 129 2 480 3 1,053 4 1,800 5 2,625 6 3,456 7 4,116 8 4,608 9 4,968 10 5,250 11 5,445 12 5,580 Average Product (AP) Marginal Product (MP) The point where marginal product reaches a maximum is called the point of diminishing marginal returns. At what quantity of labour does diminishing marginal returns set in? Graph the Total Product curve in a diagram and the marginal and average product curves in a separate graph. Isoquants and isocost lines ►BVFD: read the appendix A2 of Chapter 8. Appendix A2 introduces isoquants. ‘iso’ (or ‘ίσο’ using Greek letters) is a Greek word which means equal. Isoquant means equal quantity, isocost means equal cost. An isoquant is very similar to an indifference curve – while an indifference curve shows different combinations of goods which generate a certain level of utility, an isoquant shows different combinations of inputs which generate a certain output. Read about isoquants on pp.166–67. To find the optimal combination of labour and capital, the second tool we need to use is called the isocost line, the line showing all combinations of labour and capital (these being our two inputs in the current example) which generate the same total cost, given the prices of the two inputs – read about the isocost line on pp.167–68. It is worth pointing out that on p.167, the textbook uses the term ‘cost function’ for the C=wL+rK. However, this term is usually reserved for the equation showing cost as a function of output, not input. Given that there are only two inputs, L and K with prices w and r respectively C=wL+rK is an identity (something that is always true) – this is how we define total cost. 59 EC1002 Introduction to economics To find the optimal combination of labour and capital, the second tool we need to use is called the isocost line, the line showing all combinations of labour and capital (these being our two inputs in the current example) which generate the same total cost, given the prices of the two inputs– read about the isocost line on pp.167–68. It is worth pointing out that on p.167, the textbook uses the term ‘cost function’ for the C=wL+rK. However, this term is usually reserved for the equation showing cost as a function of output, not input. Given that there are only two inputs, L and K with prices w and r respectively C=wL+rK is an identity (something that is always true) – this is how we define total cost. Activity SG5.5 Let r = £2/hr and w = £12.50/hr. Draw a diagram with three isocost lines for when cost is equal to £50; to £100; and to £150. In the case of consumer choice, the budget line was fixed at the consumer’s budget, and the consumer maximised their utility by choosing the combination of goods which put them on the highest possible indifference curve. For the firm, for a given level of output, the firm minimises cost by choosing the combination of inputs that puts them on the lowest possible isocost line. As such, the isoquants together with the isocost curve can be used to derive the optimal combination of labour and capital that minimises the cost of producing a particular level output. In turn we can find the firm’s total cost function at different levels of output. Read about this on p.168. The optimal combination of labour is at a tangency between the (lowest) iscocost and isoquant i.e. where the slope of the isocost line is equal to the slope of the isoquant. This is where the Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution (MRTS) – a concept analogous to the MRS for indifference curves – is equal to the ratio of the price of capital and wage (the relative factor price). That is: MPK r MRTS = = MPL w Or else: Slope of the isocost line = - MPK r =slope of isoquant. = w MPL This result has an intuitive explanation; namely, that the firm must buy resources such that the last pound spent on K adds the same amount of output as the last pound spent on L. This can be easily seen by further rearranging the equations above to give: r w = MP MPk L 60 Block 5: The firm Activity SG5.6 Use the information below to draw isoquants and isocost lines and find four points on the firm’s total cost curve. Rental rate of capital = £2 per hour Wage = £2 per hour Cost levels: £12, £16, £20 and £24. Output combinations: Qx = 25 Qx = 50 Qx = 75 Qx = 100 Capital Labour Capital Labour Capital Labour Capital Labour A 1 8 2 10 3 10 4 10 B 2 5 3 6 4 7 5 8 C 3 3 4 4 5 5 6 6 D 5 2 6 3 7 4 8 5 E 8 1 10 2 10 3 11 4 What is the slope of the isocost lines? What is the MRS at the points where the isoquants are tangent to the isocost lines? What does this imply about the firm’s total cost curve? Productive efficiency The fact that the total cost curve shows the least-cost method of producing each output level implies that the points on the long-run total cost curve are productive efficient. It is important to note that every point on a firm’s average total cost curve is, by definition, productive efficient – not just the minimum point. Productive efficiency occurs when a certain quantity of a good is produced at the lowest possible input cost. Saying the same thing in a different way – productive efficiency means that the firm is obtaining the maximum possible output from its inputs. Activity SG5.7 A firm Sam’s Lamps has the production function Q(L, K) = L*K. Given labour of 5 and capital of 7, are they producing efficiently by producing 12 units? What level of production is the productive efficient level? What reasons might there be for not producing efficiently? Now suppose that Sam’s Lamps has decided to produce 100 lamps and the price of labour is £5 per unit and the price of capital is also £5 per unit. The firm decides to employ 50 units of capital and 10 units of labour. Is this efficient? Hint: with this production function the marginal product of labour is equal to K and the marginal product of capital is equal to L. Input price changes and input substitutability The discussion of the effects of changes in the price of inputs (the wage level or the rental price of capital) on p.169 is equivalent to the discussion of the change in the price of goods for consumer choice. In that case, we identified income and substitution effects of a price change – here, we identify output and substitution effects. The shape of the isoquants reflects how easy or difficult it is to substitute between inputs such as labour and capital. This is called the ‘substitutability of inputs’. The two figures below display isoquants for different production functions. Figure (a) reflects a production function where there are only limited opportunities for input substitution. If labour 61 EC1002 Introduction to economics is increased significantly (in this example, eight-fold), capital can still only be reduced by a small amount (5 units) for the level of production to be maintained. On the other hand, figure (b) reflects a production function with more abundant opportunities for input substitution – if the firm increases its employment of labour from 25 to 200, it can reduce its employment of capital substantially, from 80 to 35. K K a 80 a 40 35 b 25 Q = 50 b 35 200 L Q = 50 200 L 25 (b) Production function with abundant input substitution opportunities (a) Production function with limited input substitution opportunities Figure 5.2: The shape of isoquants and opportunities for substitution. Activity SG5.8 To produce a subject guide, one author and one computer are perfect complements in production. One author and two computers would not be more productive. Two authors would be more productive (i.e. produce two subject guides) – but only if they each have a computer. Draw the relevant isoquants for this case. Profit = Total revenue – Total cost ► Now come back to section 7.5 and 7.6 of BVFD. The focus of BVFD section 7.5 is the relationship between marginal revenue, marginal cost and output choice to maximise profits. The section 7.6 discussion on the relative size of marginal cost and marginal revenue, used to identify when increasing output increases or decreases profits, is very important. It is very helpful to understand this when you are working with whole numbers. However, you must also study the calculus treatment of marginal revenue and marginal cost in Maths A7.1 and Maths A7.2. Pounds Having used isoquants and isocost lines to derive the total cost curve, we return to section 7.4. Table 7.3 on p.128, which contains data for a certain firm. We can use this to graph the firm’s total cost function, as follows: 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 TC 0 1 2 3 4 5 Output Figure 5.3: Total cost. 62 6 7 8 9 10 Block 5: The firm This curve shows how much it costs the firm to produce any output level for given technology. It represents the total economic cost of production at various levels of output. The firm knows its total cost curve. We also assume it knows the demand curve it faces. Knowing the demand curve, the firm can calculate the revenue it would receive at various output levels and derive its total revenue curve. 25 Price 20 15 10 5 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Quantity Figure 5.4: Demand curve. 140 120 TR X Pounds 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Output 7 8 9 10 Figure 5.5: Total revenue. For example, point X on the demand curve shows the firm will sell 7 units of output at £15, generating revenue of £105. Point X on the total revenue curve therefore shows the combination of 7 units of output and revenue of £105. Putting the total cost and total revenue curves together allows us to find the profit function (profit as a function of output). For example, when total cost and total revenue are equal, profit is zero. At 6 units of output, the gap between the two curves is greatest, and this is the highest point on the profit curve, showing a profit of £27. 63 Pounds EC1002 Introduction to economics 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 TC TR 0 2 4 12 Output 6 8 10 6 8 Output 10 Profit 12 Profit Pounds 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 –20 0 2 4 Figure 5.6: Total cost, total revenue and profit. ► BVFD: read section 7.5, section 7.6, Maths A7.1 and Maths A7.2. Marginal analysis Marginal analysis is one of the key analytical tools in economics. We have already covered marginal utility in the previous block. This section introduces marginal cost and marginal revenue. ‘Marginal cost’ (MC) is the change in total economic cost due to the production of one more unit of output. ‘Marginal revenue’ (MR) is the change in total revenue due to the sale of one more unit of output. At the profit maximising level of output, marginal cost and marginal revenue are equal. Both maths boxes involve calculus, which helps to simplify the analysis. You should work through these maths boxes to understand the principles they are expounding. Activity SG5.9 If the firm faces the demand curve: P = 25 – 2Q: a. fill in the blanks in the table below b. draw the marginal cost and marginal revenue curves c. find the profit maximising output level for this firm. How much profit is the firm earning at that point? Assume output must be in integers. Output 64 Price Total revenue Total cost 0 8 1 23 2 34 3 42 4 49 Marginal Revenue Marginal cost Profit Block 5: The firm 5 55 6 65 7 78 8 93 9 110 10 130 Cost, production and output ► BVFD: read section 8.3. TP increasing marginal returns Output Output This section explores firm costs in the short run. The first few sentences of this section state that the firm’s production function can be translated into a relationship between cost of production and output. In the jargon of economic theory there is a ‘duality’ between cost and production. We do not explore this duality rigorously; however, you should appreciate that when the costs of inputs are given to the firm, then how much it costs to produce some level of output will depend on the amount of inputs needed to produce that output and that the latter will reflect the firm’s production function. The following diagram shows how total and marginal product are related to total and marginal cost: decreasing marginal returns increasing marginal returns costs increase at a decreasing rate TC costs increase at an increasing rate Q MP L Cost Cost L decreasing marginal returns costs increase at a decreasing rate MC costs increase at an increasing rate Q Figure 5.7: Relationships between total and marginal product and total and marginal cost. The top left figure shows the total product curve, which is initially displaying increasing marginal returns and then displays decreasing marginal returns after the dotted line. This is a mirror image of the total cost curve depicted in the figure below it. When marginal returns are increasing, costs are increasing at a decreasing rate, and vice versa. The slope of the TP curve gives the marginal product, while the slope of the TC curve gives marginal cost. The total product curve is also related to the marginal product curve (top left figure). The marginal product curve 65 EC1002 Introduction to economics displays increasing marginal returns by increasing up to a maximum point, and then falling when marginal returns are decreasing. The marginal cost curve below is the mirror image of the marginal product curve and demonstrates the rate of change of costs more explicitly – it falls when costs are increasing at a decreasing rate and rises when costs are increasing at an increasing rate. In this section you are introduced to fixed costs for the first time. These are costs that have to be paid even if the firm produces a very small amount greater than zero. However, at zero, the total cost is zero. Thus, there is a jump in costs at zero. For this reason, you must compare profits at some positive number with zero to see whether the firm should produce or would prefer to shut down. This is done by requiring that, in addition to the MC = MR condition (profit maximisation), that total revenue ≥ total cost or equivalently average revenue ≥ average cost (profit is not negative i.e. losses). If the best the firm can achieve by producing is losses, then it will prefer not to produce. Remember that the relevant cost is economic cost. This depends on the timescale over which you are looking. This section introduces various short run cost curves. It is important to understand what they represent, but also to practice sketching them. Activity SG5.10 Why does the SMC curve cut the SAVC and SATC curves at their minimum points? Provide an intuitive answer. ► BVFD: read Maths A8.2. This maths box provides formulas for the various short-run costs based on a short-run total cost function. You need to remember that: • Total cost = Fixed cost + Variable cost • Marginal cost is the change in total cost as quantity produced changes • Average costs are calculated by dividing the cost by the quantity produced; this applies to average fixed cost, average variable cost and average total cost. The relationship between marginal cost MC and average costs AC is very important. You need to remember that AC is increasing if MC > AC, and decreasing if MC < AC, and have some understanding of why this is so. To see why average cost must rise if marginal cost is above the average and fall if marginal is below average, imagine you calculate the average age of people in a room full of university students – if the next person to walk into the room (the marginal person) is an old lady, the average age in the room will rise. Similarly, if a baby crawls into the room, the average age will fall. You can get the relationship between average and marginal cost by noting that: AC(q) = MC(q) = 66 TC(q) q dTC(q) dq Block 5: The firm If your calculus and algebra are good enough, you can move beyond what you are expected to know for EC1002: use the quotient rule to find the derivative of AC, then do some algebra: daC(q) dq q = = = dTC(q) dq – dq dq TC(q) q2 qMC(q) – TC(q) q2 1 q (MC(q) – AC(q)) Hence dAC(q)/dq is positive if MC (q) > AC (q), in which case AC (q) is increasing; it is negative if MC (q) < AC (q), in which case AC (q) is decreasing. Activity SG5.11 Find the short-run fixed cost, variable cost, marginal cost, average fixed cost, average variable cost and average total cost for the short-run total cost function STC = M + aQ2, for which the first derivative is 2aQ. • short-run fixed cost • short-run variable cost • short-run marginal cost • short-run average fixed cost • short-run average variable cost • short-run average total cost.. The output decision ► BVFD: read section 8.4 and complete activity 8.1. This section discusses how the firm chooses its level of output in the short run. Two points are important: firstly, the output level at which profit is maximised is where marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue. Secondly, the firm must check whether the price it receives at this output level enables it to (a) cover all of its costs, (b) cover only its variable costs and perhaps contribute a little towards the fixed costs, or (c) not even cover its variable costs. Note, price received is not necessarily equal to marginal revenue. In fact, this will depend on the demand curve the firm faces. If the demand curve is horizontal, marginal revenue will always equal price. If the demand curve is downward sloping, the marginal revenue curve will also be downward sloping, as in Figure 8.7, and price will be higher than marginal revenue. Whether the demand curve is horizontal or downward sloping depends on whether or not the firm is a price taker, passively accepting the market price. We will come back to this in detail in the next blocks where we examine perfect competition and pure monopoly – two market structures where the demand curves facing the firm are quite different. The key point to note is that: The firm’s short-run supply curve is its marginal cost curve above the average variable cost curve. The firm will supply the output at which SMC is equal to MR, provided that price is not less than the firm’s SAVC. 67 EC1002 Introduction to economics Production, costs and output in the long run ► BVFD: read section 8.5 and 8.6 We now move on to the long run, and examine production, costs and the output decision as we did for the short run. The contents of this section should be familiar as this material is a descriptive version of what is in the appendix of Chapter 8. Read through carefully and make sure you are familiar with these ideas, including the concept of factor intensity. The U-shaped average cost curve is important to understand and is discussed further in the following section. The relationship between average and marginal costs (already demonstrated algebraically) is also important and applies both in the short run and in the long run. ► BVFD: read section 8.7, cases 8.3 and 8.4 and Maths 8.3. If five workers and five machines can produce 1,000 soft toys, how many soft toys could be produced if we employed 10 workers and 10 machines? This question has to do with returns to scale in production. Does doubling inputs result in more than double, less than double or exactly double the original output? This will tell us if there are increasing, decreasing or constant returns to scale. Some textbooks, but not BVFD, make a distinction between returns to scale in production and economies of scale in costs. Thus, on the production side if there are constant returns to scale then a doubling of all inputs leads to a doubling of output; and with increasing (decreasing) returns to scale a doubling of all inputs more (less) than doubles output (see Maths 8.3). As long as input prices are held constant then the relationship between returns to scale in production and economies of scale in costs is straightforward: if doubling inputs more than doubles output then cost per unit of output is smaller at higher output. However, if input prices change as output increases or decreases then the effect of these changes, as well as underlying scale effects in production, will affect average costs. The fact that BVFD equates the two concepts implies an underlying assumption that input prices are not changing as output increases or decreases. Figure 5.8 demonstrates varying returns to an increase in inputs at different levels of input. First let us describe what is meant by the ‘composite input’ on the x-axis. This is a combination of labour and capital where the proportions of each are held constant. Thus, for example, if we double labour, we also double capital and the capital–labour ratio remains the same. A change in scale does not have to do with changing the composition of inputs, but rather with changing the amount that is employed. 68 Output Block 5: The firm Long-run production function Composite Input Figure 5.8: Long-run production function. We can now see how this curve demonstrates initially increasing, then constant, and finally decreasing returns to scale. The vertical bars rising up from the x-axis are evenly spaced. However, the quantity of output generated from these input levels varies greatly. At low levels of input, increasing the units of input increases the level of output more than proportionally, representing increasing returns to scale. At high levels of inputs and outputs, the opposite is the case, since increasing the level of inputs increases the level of outputs less than proportionally, representing decreasing returns to scale. Section 8.7 discusses some real-world reasons behind returns to scale and discusses why firms may face a U-shaped long-run average cost curve. You should understand the reasons why LRAC may fall initially, be constant for some time, and then increase. ► BVFD: read section 8.8. The only difference to the analysis of the output decision in the short run is that there are no fixed costs, since all inputs are variable in the long run. For this reason, the concept of it being worthwhile to produce as long as variable costs are more than covered has no relevance and the firm simply chooses its output level where MR = LMC, and then checks if this is profitable using the LRAC curve. The firm’s long-run supply curve is its marginal cost curve above the average cost curve. The firm will supply the output at which LMC is equal to MR, provided that price is not less than the firm’s LRAC. ► BVFD: read section 8.9. The short-run cost curve shows the costs for when one input is fixed at a certain level. If it were fixed at a different level, the short-run cost curves would also be different. For example, if the level of capital was fixed at a higher level, short-run costs for producing a given level of output may be lower, if each worker is more productive with more capital to work with. There is a different short-run cost curve for each quantity of the fixed input. This is sometimes described as a family of short-run cost curves. In the long run the firm chooses the plant size with the lowest average cost for any given level of output. The LAC includes one point (assuming there are a large number of feasible plant sizes) from each SAC (not necessarily 69 EC1002 Introduction to economics the minimum point of the short-run curve, as the text explains). The longrun average cost curve can be described as an envelope of these short-run curves. Activity SG5.12 Draw six short-run average cost curves, each with a single point of tangency to a long-run average cost curve showing increasing, constant and then decreasing returns to scale. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. Overview This block has demonstrated what lies behind the firm’s production decisions. Using isoquants and isocost curves, the firm can determine the least-cost combination of inputs to produce a given quantity of output. From there, the firm’s total cost curve can be derived. It is assumed that firms pursue a goal of profit maximisation, where Profit = Revenue – Cost. Knowing the demand curve it faces, the firm can derive its revenue curve, and since it knows both revenue and cost, the profit-maximising level of output can easily be found, which is where marginal cost and marginal revenue are equal. Marginal analysis is a very useful tool in economic analysis, as we have seen here in the case of the firm. The distinction between the short run (when one factor of production is fixed) and the long run (where all inputs are variable) is important. The production function, which summarises the technical possibilities faced by the firm, can be used to derive the firm’s total cost curve. Short-run total cost is equal to short-run fixed cost plus short-run variable cost. Average costs are found by dividing cost by quantity produced. Average cost is falling if marginal cost is below average cost and rising if marginal cost is above average cost. The short-run marginal cost curve reflects the marginal product of the variable factor (usually labour). It cuts the SATC and SAVC curves at their minimum points. In the short run, the firm choses its output level where MC = MR, but only produces at all if the price received at this level of output at least covers all variable costs and makes some contribution to fixed costs. The long-run total cost curve represents the economically efficient (least-cost) production method for each level of output when all inputs can be varied. The long-run average cost curve is usually U-shaped, representing increasing, constant and then decreasing returns to scale as output rises. In the long-run, the firm supplies the output at which MR = LMC as long as the price is no less than LAC at that level of output. The LAC curve is an envelope of many SAC curves which all touch the LAC at just one point. This block showed how the short-run and long-run supply curves of an individual firm can be found. You need to be able to reproduce the output curves and cost curves covered in this block. Since there are quite a few, the best way to do this is to understand what they mean, why they have certain shapes, and how they are related to each other. The examination will test your understanding of these cost concepts (rather than just your capacity for memorisation). ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. 70 Block 5: The firm Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. Anita owns a grocery shop. These are her annual revenues and costs: Revenues: £250,000 Supplies: £25,000 Electricity and heating: £6,000 Employees’ salaries: £75,000 In addition to the above, Anita pays herself a salary of £80,000 and accumulates any remaining profits. If she closed her shop, she could rent out the land and building for £100,000. Due to her experience at running her own shop the local supermarket would offer her a job and pay her £95,000. a. Anita’s revenue exceeds her economic costs so she should continue running her business. b. Anita’s economic costs exceed her accounting costs so she should shut down her business. c. Anita’s economic costs exceed her revenue so she should shut down her business. d. Anita’s salary is less than what the supermarket would pay so she should shut down her business. 2. Suppose the short-run total cost of producing T-shirts can be represented as STC = 50 + 2q where q is the level of output. The average and marginal costs of the 5th T-shirt are: a. £50 and £2. b. £12 and £2. c. £50 and £10. d. £12 and £10. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. A publishing company is selling books. To do so they need to employ proofreaders and assign them computers. Hiring more proofreaders without assigning them computers cannot increase the number of books produced. 2. When long-run costs for a firm are at a minimum the extra output we get from the last dollar spent on an input must be the same for all inputs. 3. A car manufacturer invests in a factory and machinery (capital), which they cannot modify in the short run. They also employ workers on a yearly contract. If the rent needed for the factory and machinery, the wages paid to the employees and prices do not change, the long-run 71 EC1002 Introduction to economics cost of producing a good must be lower than the short-run cost of producing the same good, as no inputs are fixed in the long run. Long response questions 1. Bob Smith manages a branch office of a large financial services firm. He uses computers (capital, K) and people (labour, L) to produce consulting advice Q, according to the production function: Q = KL. The marginal product of labour is equal to K and the marginal product of capital is equal to L. Employing people costs the wage rate w = 1 while renting computers costs the rental rate r. Suppose computers cost twice what people do (i.e., r = 2w = 2). The number of computers in the branch is fixed at K = K. a. How much labour does Mr Smith employ if he needs to produce output Q? Show that total cost is C(Q)= 2K +Q/K . b. Given that the first derivative of the total cost function above is 1/K, derive average and marginal cost. How do average and marginal cost vary with output? Explain using a graph. c. Corporate headquarters has just authorised Mr Smith to upgrade the branch office by varying the quantity of computers. What is the optimal (cost-minimising) mix of capital and labour? 2. A car manufacturer invests in a factory and machinery (capital), which they cannot modify in the short run. They also employ workers on a yearly contract. If the rent needed for the factory and machinery, the wages paid to the employees and prices do not change, the long run cost of producing a good must be lower. 72 Block 6: Perfect competition Block 6: Perfect competition Introduction Our study of microeconomics now looks in greater depth at different types of market structure, which refers to the economic environment in which buyers and sellers in an industry operate. It is generally defined according to four characteristics: the size and number of buyers and sellers, the extent of substitutability of different sellers’ products, the extent to which buyers are informed about prices and available alternatives and the conditions of entry/exit. Although BVFD covers the two extremes of market structure (perfect competition and pure monopoly) in one chapter, this subject guide devotes a block to each, enabling some issues to be covered in a bit more depth. In perfect competition (Block 6), there is a very large number of firms and free entry and exit, whereas in monopoly (Block 7), there is a single firm which supplies the whole market, and very large barriers to entry into the market. While many real-world firms do not fit neatly into these two extremes, it is nonetheless worthwhile to study them first, partly because they do approximate some real-world markets (see below for examples), but also because they provide a benchmark that is very useful for comparison with other market structures which are more commonly encountered in the real world. Perfect competition is a desirable market structure in terms of maximising the welfare of market participants and for this reason is often used by economists as a kind of first-best standard in order to evaluate the welfare losses caused by deviations from the competitive ideal. The subsequent block (Block 8) will introduce other market structures (monopolistic competition and oligopoly), which sit on the continuum in between these two extremes. The study of both perfect competition and monopoly relies on knowledge from Blocks 4 and 5, so make sure you are familiar with that material first. In particular, you need to fully understand why choice of the profit maximising output requires firms to equate marginal cost and marginal revenue. You should also recall that the return needed to keep a firm from leaving the industry is already included in its cost curves, which include all opportunity costs – including the next best alternative return to operating in the current market. In the long run if a firm is earning a price above average cost it is earning abnormal, supernormal, or economic profits (these three terms tend to be used synonymously in economic texts). Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • define perfect competition • describe why a perfectly competitive firm equates marginal cost and price • demonstrate how profits and losses lead to entry and exit • draw the industry supply curve • carry out comparative static analysis of a competitive industry. 73 EC1002 Introduction to economics Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 9, sections 1 to 4. Synopsis of this block This block introduces the market structure perfect competition. It starts by outlining the underlying assumptions and the implications of these, notably that firms in a perfectly competitive market face a horizontal demand curve and act as price takers, with no ability to influence the market price. This also means that MR = P for perfectly competitive firms. The block then describes the firm’s short-run supply decision and shortrun supply curves. In the short run, firms will stay in business if P > AVC, even if they are making a loss, however, in the long run, they will exit the market unless P ≥ AC. The firm’s long-run supply curve is flatter than the short-run supply curve since it can adjust all inputs in the long run. The industry supply curve is the horizontal summation of all the individual firms’ supply curves. In the long run, firms can exit and enter the market. This provides a further reason why the long-run industry supply curve is flatter than the short-run industry supply curve. The chapter also discusses how firm and industry supply curves are affected by an increase in costs or a change in the market demand curve. Assumptions and implications ► BVFD: read the introduction to Chapter 9, section 9.1 and concept 9.1. Perfect competition is a model of market structure. It rests on the following assumptions: 1. Many firms, each negligible in size relative to the entire industry. 2. All firms produce homogenous goods. 3. Perfect information regarding prices and available alternatives. 4. Free entry and exit. From these assumptions, the key implication is that the individual firms in this market face a horizontal demand curve. All act as price-takers, with no ability to influence the market price. The textbook mentions the market for corn as a market which closely resembles a perfectly competitive market. Other examples of markets which may approximate perfect competition – at least along certain dimensions – include forex (foreign exchange) and agricultural commodities such as cocoa. Activity SG6.1 For the forex market (e.g. selling US dollars), note down how and to what extent each of the four assumptions above are met. In reality, there are not many markets which are truly perfectly competitive. Nonetheless, for the reasons described in concept 9.1, it is still a very useful model to study. 74 Block 6: Perfect competition The firm’s supply decision ► BVFD: read section 9.2. In the previous section, it was established that the negligible size of individual firms in a competitive market means that each firm faces a horizontal demand curve. At the beginning of this section, it is shown that this means, for price taking firms, that price equals marginal revenue. Be sure you understand this; if you do you will also understand why MR < P for a firm facing a downward sloping demand curve. We will return to this point when we discuss monopoly. For an individual firm, we can write its revenue as TR = P*Q. Dividing by Q we have TR = AR = P Q Because the firm is a price taker, P is a constant term in this equation. Therefore, changes in TR come about via changes in Q. ∆TR = P∆Q or ∆TR = MR = P ∆Q Marginal revenue, the increase in total revenue when output increases by one unit, is just the price received for that output. We can show TR as a function of Q graphically as follows: TR TR Slope=P Q Figure 6.1: Total revenue for a competitive firm. 75 EC1002 Introduction to economics This enables us to provide a diagrammatic treatment of profit maximisation for a competitive firm. TC TR TR, TC Panel (a) Q1 Q2 Q3 Q (output) Q4 Profit, π Profit, π, (TR–TC) Panel (b) Q1 Q2 Q3 Q (output) Q4 £ MC AC D=AR=MR Profit, π Panel (c) Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q (output) Figure 6.2: Profit maximisation for a competitive firm. In panel (a), a total cost curve (with fixed costs in the short run and increasing marginal cost) is superimposed on the TR curve. Profit, which we denote by π, is the vertical distance between total revenue and total cost. It is positive between Q1 and Q4. For output lower than Q1 or greater than Q4 the firm makes a loss. Geometrically, profit is maximised when the vertical distance TR–TC is greatest (between Q1 and Q4). This occurs at Q3, where the slope of TR is equal to the slope of TC. These two slopes are MR and MC respectively, so profit is maximised when output is chosen such that MR = MC (or P = MC, as MR = P). Panel (b) simply graphs profit, π, against output. Profit maximisation means getting to the top of the ‘profit hill’, again at Q3, of course. Panel (c) shows the same process in a third equivalent way, using the firm’s demand and cost curves (the MC and AC curves corresponding to the TC curve in panel (a)). Profit maximising output is at Q3 where MC = MR. The shaded area shows the firm’s actual profit; it is AR – AC, which is profit per 76 Block 6: Perfect competition unit at Q3 multiplied by the number of units this is earned on, namely Q3. Equivalently it is TR (= AR*Q3) minus TC (= AC*Q3). Thinking of the economic intuition rather than the geometry of the MC = MR (or MC = P) requirement, we can examine the firm’s position when MC and MR are not equal, say at Q2 in Figure 6.2. Clearly in panel (b) this is not at the summit of the ‘profit hill’. Panel (c) shows why. At output Q2, MR>MC. What does this mean? It signifies that at Q2 increasing output by one unit adds more to revenue than to cost, so increasing output increases profit. The marginal benefit of increasing output exceeds the marginal cost. You should be able to see, by the same reasoning, that if output is greater than Q3, the marginal benefit of contraction exceeds the marginal cost. You also need to revise, from section 8.4 of BVFD, the so-called shut down condition (if price falls below short-run variable cost the firm should not produce any output). It may initially seem counterintuitive for a firm to produce output in the short run even if it is making a loss. How can this be? Think about a firm’s short-run fixed costs, rentals on building and machines, insurance premiums, contractual management fees, etc. These are unavoidable even if the firm produces zero output. But losses never have to be greater than these fixed costs. Any variable costs, costs that vary with the level of output, can be avoided by not producing. If these variable costs can be more than covered by producing some output then the ‘profit’ on the cost of variable inputs can contribute to paying for the unavoidable fixed costs, even if the firm is making a loss overall. Short-run supply decision The firm’s short-run decision can be summarised as follows: • The price is determined by the market (by market supply and demand). • For a perfectly competitive firm, P = MR. • A profit maximising firm produces where MR = MC. Because P = MR, this means that a perfectly competitive firm operates where P = MC. • The optimal quantity to produce is indicated by the SMC curve, which is the firm’s short-run supply curve – the firm chooses quantity where P = MR = SMC. • The firm will only produce if the price lies above its SAVC curve and only covers all their costs if it is at least equal to its SATC curve. Activity SG6.2 Draw the short-run cost curves of a perfectly competitive firm and indicate prices at which they … and the quantities they will produce at each of these prices: a. Make supernormal or economic profits b. Will not produce in the short run. c. Just cover all their costs. The marginal firm If the price level is below the lowest point on the firm’s LAC curve, firms will exit the market in the long run, as they would otherwise be making losses. But how do we know which firms will exit? In theory, firms have access to the same technology and will thus have the same costs curves in the long run, when enough time has passed for full adjustment of capital to be made. This assumption is also made in BVFD – that all firms in the market and the potential entrants have identical cost curves. In this case, which firms exit and which stay would be quite random. However, in the 77 EC1002 Introduction to economics real world, firms will not all have identical cost curves, since technology is changing continually and firms have different histories. For example, some firms will have replaced their capital stock more recently than others. In a situation where no firms are covering their long-run opportunity costs, the marginal firm will be the first one whose capital comes up for replacement. This firm will exit first. It is very important to understand that the two conditions (price = marginal cost) and (price = average cost) are there for entirely different reasons. Price = marginal cost is a consequence of profit maximisation under perfect competition and must always hold. Price = average cost is a zero profit condition which is driven by free entry and exit in the situation in which all firms have the same cost function. BVFD assumes that all the firms are identical. Activity SG6.3 Reproduce Figure 9.4 from the textbook, except to show exit, not entry. Industry supply curves ► BVFD: read section 9.3. It is crucial to distinguish carefully between supply curves for an individual competitive firm and supply curves for the industry (the market as a whole) – the industry supply curves are the horizontal summation of all the individual firms’ supply curves. In each case it is also important to distinguish between the short run and the long run. The previous section showed that the long-run supply curve for a firm is its LRMC curve above minimum LRAC. Note that this is average total cost not average variable cost, because while it may be rational to make a loss in the short run (if variable costs are more than covered and revenues make a contribution to covering fixed costs), this is not the case in the long run. In the long run, if a firm cannot cover its costs it should leave the industry. When firms leave the industry, industry supply shifts inwards and price increases. This process continues until revenues just cover costs for remaining firms in the industry. On the other hand, if firms are making abnormal or economic profits then new firms will enter the industry and drive down the price. This process continues until firms are just covering all opportunity costs (i.e. no abnormal profits are being earned). The long-run industry supply curve is flatter than its short-run counterpart. It is possible that the longrun industry supply curve is horizontal, and this is the ‘pure theory’ result with perfectly elastic supply of inputs. However, due to the likelihood that input prices will increase as an industry expands, as well as due to the fact that, in practice, firms have different cost curves, it is much more likely that the long-run industry supply curve will be upward sloping. Comparative statics ► BVFD: read section 9.4. This section is vital for your understanding of competitive markets. If you fully understand the consequences, both at the level of individual firms and the industry as a whole, of shifts in the market (industry) supply or demand curves then you will have mastered an important building block of microeconomic analysis. The essential point is that entry or exit from the industry ensure that individual firms have zero profits (remember this can 78 Block 6: Perfect competition be compatible with a return to management and entrepreneurship – these are included in the cost function; they are opportunity costs, namely what managers and entrepreneurs could earn in the next best activity). This means that in the long run, price must return to the minimum ATC, making the long-run supply curve horizontal as long as expansion or contraction of the industry does not change input prices. The two activities are designed to assist your understanding of this. Note that in this section, at the industry level, the short-run supply curves hold constant the number of firms in the industry (at the level of the individual firm the short-run corresponds, as usual, to one or more of the firm’s inputs being fixed). The section on shifts in the market demand curve demonstrates that the short-run industry supply curve is much less elastic than the long-run industry supply curve. In the short run, firms cannot respond as much to a change in price and the number of firms is fixed. As such, an increase in demand has a much greater impact on price in the short run compared to the long run. Activity SG6.4 Reproduce both graphs in Figure 8.8 but for an increase in demand, rather than an increase in costs (the textbook also suggests this activity and already provides the industry side). Perfect competition and efficiency One of the reasons given in concept Box 9.1 for studying competitive markets is that ‘a perfectly competitive market has some desirable properties in terms of efficiency of the market outcome’. In this setting competitive markets are efficient in the sense that they maximise the sum of consumer and producer surplus (effectively profits in this context). However, this does not imply that a move to competitive markets is better for everyone. For example, monopoly is better for the owners of a firm than perfect competition because profits are higher. However, the sum of consumer and producer surplus are larger under perfect competition. Later in the course (Block 10/BVFD Chapter 14) you will encounter a much more precise statement of the efficiency properties of perfect competition. Under strong conditions, which you will study in detail in EC2066 Microeconomics if all markets are perfectly competitive then the outcome is Pareto efficient, that is it is impossible to make someone better off without making someone else worse off. However markets may fail to work in this way. You will learn more about market failure in Block 11. In particular, externalities imply that the supply curve may not represent marginal social cost. Another reason why the supply curve may not represent marginal social cost is if there is imperfect competition in the market supplying inputs to the industry. Using the competitive model: a worked example Assume that the raspberry growing industry in Scotland is perfectly competitive, and each producer has a long-run total cost curve given by: TC = 144 + 20Q + Q2 and its marginal cost by MC = 20 + 2Q. The market demand curve is: ∼ Q = 2,488 – 2P ∼ (Q is the demand in the market, Q is the output of an individual firm). 79 EC1002 Introduction to economics a. What is the long-run equilibrium price in this industry? b. How many active producers are in the raspberry growing industry in a long-run competitive equilibrium? c. Illustrate diagrammatically the long-run equilibrium of the firm and the industry. Your diagram does not have to be drawn to scale but should contain the relevant information. Solution a. The first thing we have to realise is that the question is concentrating on the long-run, so it is the properties of long-run equilibrium that are going to be relevant in solving this problem. In the competitive model free entry and exit ensure that firms are earning zero profit (they just cover all opportunity costs). This is a vital step in solving the problem. Zero profit means that TR = TC for each firm, i.e. PQ = 144 + 20Q + Q2 But this is not yet helpful to us because it is one equation with two unknowns. What can we do? Well our model of the competitive firm also tells us that it will produce where P = MC. We are given MC so we can substitute in to the left hand side of the equation above: (20 + 2Q)Q = 144 + 20Q + Q2 This gives us Q2 = 144, i.e. Q = 12 Now from P = MC we know P = 20 + 2Q, i.e. P = 44. b. Now turn to the market demand curve and substitute in this price to estimate market demand: ∼ Q =2488 – 2 * 44 = 2,400 So now we know that market demand is 2,400 and that each profit maximising competitive firm produces 12 units. Therefore the number of firms in the market must be 2,400/12 = 200 c. The diagrams are shown below. Make sure that you label the axes and any curves or lines in the diagram as well the solution values of prices and quantities. LRMC P, AC, MC P Market demand LRAC Market supply 44 44 12 Q 2400 Figure 6.3: Long-run equilibrium of the firm and the industry. Overview A market structure is the economic environment in which buyers and sellers in an industry operate. This block covered perfect competition and its underlying assumptions, including that: 80 Q Block 6: Perfect competition • there is a large number of buyers, all small relative to the whole market and all producing a homogeneous product • buyers and sellers have perfect information regarding prices and available alternatives • there is free entry and exit. In a competitive industry, buyers and sellers are price-takers and have no influence over the market price. Price is equal to marginal revenue and the firm choses output where P = MR = MC. In the short run, the firm’s supply curve is its SMC curve above SAVC. In the long run, the firm’s supply curve is its LMC curve above its LAC curve. The industry supply curve is obtained by horizontally adding the supply curves of the individual firms. The long-run industry supply curve is flatter than the short-run industry supply curve both because firms can fully adjust their inputs and also because firms can enter or exit the market. Graphical analysis of short-run and long-run supply curves was carried out for both the perfectly competitive firm and the perfectly competitive industry. These are affected by changes in costs and in the market demand curve, leading to a new equilibrium. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. An increase in the cost of capital will have the following effect on a perfectly competitive market: a. Short-run average and marginal cost will increase which would lead to a fall in output and an increase in price. In the long run, firms will leave and price will rise further. b. Short-run average and marginal cost will not change but there will be a fall in output and an increase in price. In the long run, firms will leave and price will rise further. c. Short-run average cost will increase but there will be no change in output or price. In the long run, firms will leave and price will rise. d. Short-run marginal cost will decrease which would lead to an increase in output and a decrease in price. In the long-run, firms will enter and price will become stable. 2. The inverse supply function in the market for cherries has equation Q 3Q . The inverse demand function has equation pD =12 - 2 .What are ps = 2 the equilibrium price p and quantity Q? a. P=6,Q=4 b. P=6,Q=5 c. P=9,Q=6 d. P=10,Q= 81 EC1002 Introduction to economics 3. Which of the following statements characterises a perfectly competitive market: a. Firms have an incentive to set a price below the marginal cost of production. b. Firms produce goods that have a large number of complements. c. Firms have no incentive to set a price above the marginal cost of production. d. Firms produce at the lowest point of their average variable cost curves. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. The market for mangoes is perfectly competitive. This year, an increase in the number of storms lowered the productivity of mango trees. Hence, we should expect both the short-run equilibrium price and the long-run equilibrium price in the market for mangoes to increase. 2. The market for beer is perfectly competitive. If a tax is imposed on the production of beer, beer will become more expensive. 3. In the market for tablecloths each firm has the cost function C(q)=5q. This means that the supply is horizontal in this market. Long response question 1. Suppose all firms in a perfectly competitive market are initially in both short-run and long-run equilibrium. Then a lump-sum tax (i.e. a tax that is unrelated to a firm’s output) is introduced. a. Draw a diagram to illustrate the effects of the lump-sum tax on an individual firm and the whole industry. b. What impact will this have on each firm in the short run? c. What impact will this have on market price in the long run? d. What impact will this have on each firm’s output in the long run? e. What impact will this have on the number of firms in the industry in the long run? 82 Block 7: Pure monopoly Block 7: Pure monopoly Introduction Having examined perfect competition in the previous block, this block now covers pure monopoly, which is a market structure where only one firm supplies the whole market, and thus there is no competition between firms. Utilities (such as gas or water) supplying a particular region are often monopolies (this will be explored in the section on natural monopolies). Furthermore, patents allow companies to hold a monopoly over an invention (for example a pharmaceutical drug) for a limited period of time. Although finding other real-world examples of companies that are ‘pure’ monopolists can be as difficult as identifying examples of markets that are ‘perfectly’ competitive, some companies that come close include Microsoft, in the market for operating systems, and, a historical example, de Beers diamonds, which controlled an estimated 80 per cent of rough diamond supply in the 1980s.1 This block examines the theoretical aspects of monopoly as a market structure, including how the monopolist determines its price and output, the social cost of monopoly due to inefficiency, and price-discrimination by monopolists. www.economist.com/ node/2921462 1 Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • define pure monopoly • find the optimal price and output levels for a monopolist using MC = MR • relate PED to monopoly power • recognise how output compares under monopoly and perfect competition • describe how price discrimination affects a monopolist’s output and profits. Note, that the two-part tariff (in Chapter 9.10) is not examinable. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 9 sections 5 to 10 (but not the two-part tariff). Synopsis of this block This block introduces the case of pure monopoly, with its own underlying assumptions – namely that there is only one firm supplying the whole market and large barriers to entry. The block describes the profitmaximising output for the monopolist as well as the relationship between the elasticity of demand and the monopolist’s degree of market power (measured by how far above marginal cost, and revenue, it can set the price it charges). The allocative inefficiency of monopoly is demonstrated by the loss of social surplus compared to the case of perfect competition. First, second and third degree price discrimination are explained, including the impact on the monopolist’s output, price and profits. Despite the allocative inefficiency of monopoly, one possible advantage could be that monopoly profits provide an incentive for firms to innovate. Natural monopolies display a falling long-run average cost curve over the whole range of production. Government regulation of monopolies is also discussed. 83 EC1002 Introduction to economics ► BVFD: read section 9.5. Perfect competition and perfect monopoly We turn now to the case of monopoly, which is at the other end of the spectrum compared to perfect competition. Like the latter, in its ‘pure’ form it is likely to be rather rare in practice, but studying the pure form tells us a lot about how firms behave when they have market power (i.e. when they face a downward sloping demand curve). The table below summarises how perfect competition and monopoly differ, according to the four assumptions made to describe perfect competition in section 9.1. Number of firms Nature of product Information Entry and Exit Perfect competition Very large, infinite Homogeneous Perfect Free Monopoly Homogeneous (One product) Perfect Large barriers to entry One Table 7.1: Characteristics of perfect competition and pure monopoly. In relation to the final column, BVFD in this chapter essentially rule out by assumption the entry to the industry of new firms (which would erode monopoly profits). You should think about why this happens in practice. Some barriers to entry are ‘natural’, for example the unique talents of a singer or sports star (their monopoly profits are not eroded by the entry of clones) while others are artificial, such as the monopoly position afforded, perhaps temporarily, by licences, patents, tariffs and the like. Such artificial barriers to entry can, in principle and often in reality, be removed to introduce competition into previously monopolised industries. ► BVFD: read section 9.6 and Maths A9.1 and A9.2 Monopoly analysis This section shows that profit maximisation for a monopolist, as for a competitive firm, requires producing where MR = MC. But, unlike the competitive case, MR is not equal to P – it is less than P (see next paragraph). This means that in profit maximising equilibrium, where MR = MC, P > MC and this turns out to be the source of monopoly’s inefficiency. You need to be sure that you really understand the monopoly diagram, BVFD Figure 9.11. What follows spells out in a bit more detail some aspects of the monopoly analysis. To begin with it is crucial for you to understand why, in the case of monopoly, MR < P (remember from the previous block that MR = P for a competitive firm). This is explained in section 8.6, but here it is spelled out in more detail. The downward sloping demand curve faced by the monopolist means that if a monopolist wants to sell more output it will have to lower the price. But the lower price applies to all of its output, not just the marginal unit. Marginal revenue is the price the monopolist receives for the marginal unit less the price reduction it must accept on all the units previously sold at a higher price. This is demonstrated in the following simple diagrammatic illustration. 84 Block 7: Pure monopoly P TR11 = 9.5 × 11 = 104.5 TR10 = 10 × 10 = 100 MR = TR11 – TR10 = 4.5 = P11 + 10∆P (∆P is negative) 10 9.5 D 10 Q 11 Figure 7.1: Marginal revenue when the firm faces a downward sloping demand curve. When the price is 10, 10 units are sold and total revenue received by the firm is 100. To sell an extra unit (the 11th unit) the price must fall to 9.5. This, however is not the firm’s net gain in revenue because it now sells each of the previously sold 10 units for 9.5 rather than 10. The net revenue, the marginal revenue, from selling the 11th unit is its price, 9.5, minus the reduced revenue on the first 10 units, i.e. 0.5 * 10 = 5. Therefore MR = 9.5 – 5 = 4.5. So MR is less than price. Activity SG7.1 As part of your studies of microeconomics, it is important for you to be able to draw the cost and revenue curves for a typical monopolist. a. Reproduce Figure 9.11, making note of the key points (the point where the MC and MR curves cross, the price level the monopolist chooses, and the average cost at this quantity) and highlighting the monopolist’s profit. b. Illustrate a rise in costs (as described in the section ‘comparative statics for a monopolist’). c. Illustrate an increase in demand (as described in the section ‘comparative statics for a monopolist’). As noted above, cutting the price increases demand but reduces the revenue on existing units. The effect on a firm’s total revenue depends on the price elasticity of demand, as you will remember from Blocks 3 and 5. This is described in more detail in this section, and in Maths A9.2. The formula in equation 7 (or 8) of the maths box is very useful. Although the derivation in the box uses calculus, the intuition can be seen by using the delta notation as follows2 TR = P * Q ∴∆TR = P∆Q + Q∆P Therefore we can write: MR = ∆P ∆TR =P+Q ∆Q ∆Q But PED (price elasticity of demand), ε, can be written as ε = ∆Q P . ∆P Q In fact, the expression in the text is an approximation. The full expression for ∆TR is ∆TR = P∆Q + Q∆P + ∆P∆Q. For small changes in P and Q the final term can be ignored, giving the equation in the text. 2 Substituting into the above we get, after a bit of manipulation: ( 1 ε ( =P 1– 1 |ε| ( ( MR = P 1 + 85 EC1002 Introduction to economics which is equivalent to equations (3) and (4) in Maths A9.2. Here you can see straight away that if demand is inelastic, |ε|<1, MR is negative. This shows concisely what is explained in the text, namely that a monopolist will never operate on the inelastic portion of the demand curve. Also, because MR = MC for profit maximisation, some further straightforward manipulation yields: 1 P – MC = |ε| P which is the proportionate mark-up of price over marginal cost, is sometimes used as an index of monopoly power (the Lerner Index). In the case of perfect competition this index is zero (P = MC, |ε| = ∞ ). What is the maximum value this could take in the case of monopoly? The equation: MR = P + Q ∆P ∆Q can also be used to show a useful result for MR where the demand curve is linear. Suppose the (inverse) demand curve is given by P = a – bQ where ∆P –b is ∆Q then substituting into the above equation gives MR = a – 2bQ. (Maths 8.1 shows the same result using calculus). Remember that this is the case for linear (straight line) demand curves only. The marginal revenue line has the same intercept on the P-axis as the demand curve but is twice as steep. Thus, in Figure 9.10, the MR curve crosses the horizontal axis at exactly half the quantity at which the demand curve crosses the horizontal axis – this is due to the fact that when P = a – bQ, the DD curve crosses the horizontal at a/b. The MR curve corresponding to this demand curve is MR = a – 2bQ. This curve crosses the x-axis at a/2b: exactly half the quantity at which the demand curve crosses. The following question requires you to use the result we have just explained about the slope of the MR curve relative to the slope of the demand curve in order to solve for the monopoly equilibrium: Using the monopoly model: a worked example The (inverse) demand curve faced by a monopolist is given by: P = 210 – 4Q a. Suppose the monopolist has constant marginal cost equal to 10 (MC = 10). Use the method shown above to find the monopolist’s marginal revenue and, using that, calculate the monopolist’s profit maximising output, price and total revenue. b. Now suppose that the monopolist’s MC increases to 20. Calculate the new monopoly quantity (Q), price (P) and total revenue (TR). c. Suppose now that the demand curve given above refers to a perfectly competitive industry in which each firm has a constant marginal cost of 10. What is the industry price, output and total revenue? d. Now in this competitive industry suppose that the MC for each firm increases to 20. What is the new P, Q and TR for the industry. e. Compare and comment on the change in TR for the monopoly and the competitive industry when MC increases from 10 to 20. 86 Block 7: Pure monopoly Solution a. The MR curve has the same vertical intercept but twice the slope of the demand curve. i.e.: MR = 210 – 8Q P, MR 210 D (AR) 26.25 52.5 Q Figure 7.2 The monopolist maximises profit when MR = MC, 210 – 8Q = 10. So Q = 25. Put this into the demand curve to calculate P = 110. TR = P*Q = 2,750. b. Following a similar procedure, when MC = 20, Q = 23.75, P = 115, and TR = 2,731.25. c. When the industry is perfectly competitive, the industry supply curve is horizontal at P = MC = 10. At this price the demand curve tells us that Q=50 and therefore TR is 500 (P*Q). d. By the same method, when MC = 20, industry output is 47.5, P = 20 (from demand curve) and TR = 950. e. When MC increases from 10 to 20 the monopolist’s TR falls and the industry TR increases. Why the difference? The monopolist always operates on the elastic portion of its demand curve, otherwise MR would be negative and this is never optimal. So an increase in price reduces TR – a consequence of an elastic demand curve. At the competitive output, on the other hand, for the industry as a whole the demand curve is inelastic (you can check this by calculating the elasticity or by substituting the competitive output into the MR equation and noting that MR is negative, implying inelastic demand). Of course, with inelastic demand an increase in MC and price will increase TR. For each firm in the competitive industry MR is positive and equal to price. Activity SG7.2 Consider two monopolists in two industries. One is the sole postal service operating in a country. The other is the sole producer of a certain type of cheese (no-one else has the technology to produce this cheese). Which of these do you think faces a more elastic demand schedule? Draw a rough sketch of the demand, marginal revenue and cost curves for each industry and examine the gap between the point where MC = MR and the price chosen by each monopolist. Which firm has greater market power? 87 EC1002 Introduction to economics Social cost of monopoly ► BVFD: read section 9.7. This section establishes the important result that, compared with a perfectly competitive industry, a monopolist produces less output and charges a higher price (given the same cost conditions). This is the source of the social cost of monopoly – the deadweight loss of monopoly. The intuition for this is that, with price above MC, consumers place a higher value on extra output than it costs to produce that extra output – expanding output would be socially productive under such circumstances. It is this deadweight loss, rather than the existence of monopoly profits, that economists see as the rationale for ‘competition policy’. Competition or antitrust policy works differently in different countries but will seek some mix of attempting to generate more competition in markets which are currently uncompetitive and regulating the behaviour of firms with market power, for example by setting price ceilings. Occasionally, it will be decided that monopoly is in the ‘public interest’ (not an easy concept to pin down!) and therefore its existence is allowed to continue unchecked by policy. Section 9.9 (Monopoly and technical change) returns to the potential advantages of monopoly. Our worked example and section 9.7 of the textbook uses a horizontal long-run marginal cost curve. However, remember that Section 9.3 described how, realistically, industry supply curves are likely to be upward sloping. The diagram below portrays the social cost of monopoly in the case where the long-run marginal cost curve slopes upwards. Some consumer surplus has been lost and has become monopoly profits while some has become deadweight loss. There is some producer surplus lost compared to the perfectly competitive model, but this is smaller than the supernormal profits gained by the monopolist. P Perfectly compeve market Pure monopoly P D D PM MC S PC PC MR QC Consumer surplus Q Producer surplus QM QC Deadweight loss Figure 7.3: Monopoly and (in)efficiency. The previous block described how the perfectly competitive model results in outcomes that are both productive and allocative efficient. Productive efficiency occurs because firms choose a quantity on their cost curves. This applies to monopoly in the same way. Although monopolists are not under pressure from competition to choose the cost-minimising mix 88 Q Block 7: Pure monopoly of inputs, they are still likely to do this in order to maximise profits. In terms of allocative efficiency, the perfect competition model is allocative efficient because the sum of consumer and producer surplus is maximised. This means it is not possible to make one party better off without making the other party worse off. By contrast, the monopolist is not allocative efficient. As there is a deadweight loss, by lowering the price and increasing the quantity produced, it would be possible to increase the total surplus available for distribution between the two parties. Price discrimination ► BVFD: read sections 9.9 When firms have market power (pure monopoly is the extreme case) they can, under certain circumstances, employ pricing strategies that increase their profits by ‘raiding’ the consumer surplus of their customers. We have taken it as given that there can be only one single price charged for a unit of a homogeneous good. Imagine this were not the case. There would be possibilities for mutual gains via arbitrage – those charged a low price could sell the good to those charged a high price; at intermediate prices both parties gain. Arbitrage would continue until a single price prevailed. Where such secondary markets are impossible or can be prevented by simple monitoring strategies, firms with monopoly power can increase their profits by charging different prices to different consumers. Can you think of examples where it is difficult or impossible for secondary markets to erode price differences? Make sure you understand the rather remarkable result that first-degree price discrimination eliminates the deadweight loss associated with a single price monopolist. Whereas in the case of third-degree price discrimination, by far the most common type in practice,3 BVFD show that the monopolist must equate MR in both sub-markets (make sure you understand why) and set these equal to the common value of MC. This leads to higher prices being charged in the sub-market with the more inelastic demand. We can show this more rigorously by applying the formula for MR derived above (and in Maths A9.2). 1 1 =P 1– =MR2=MC MR1=P 1– ε1 ε2 [ [ [ [ Suppose that in market 1 |ε1| = 1.5 and in market 2 |ε2| =3, then equating MR11 and MR22 gives: P1(1–1/1.5) = P2(1–1/3). This means P1/P2 = 2. The profit maximising monopolist charges twice as much in the more inelastic market 1 than in the more elastic market 2. The exact price levels can then be pinned down by equalising marginal revenues to MC. Activity SG7.3 Define first-, second- and third-degree price discrimination. For first-degree price discrimination, draw graphs illustrating producer and consumer surplus compared to a competitive industry and to a non-discriminating monopolist. 89 EC1002 Introduction to economics When can monopolies be justified? ► BVFD: read sections 9.9. Case 9.3 and 9.10. The pharmaceuticals industry provides one example of the controversy regarding monopoly and competition law. In this industry, production costs are very small and most of the costs involved are fixed costs on R&D to discover and test new medicines. Firms can patent their discoveries for a period of 10 years, allowing some time when they can sell these at a monopoly price and earn profits which help cover the R&D costs for that and other drugs. After this time, generic versions of the drugs start to be sold by rival firms and the price generally falls. On the one hand, people argue that life-saving drugs should be made available immediately, especially to developing countries. On the other hand, it is argued that without the monopoly period provided by the patent, firms would have no incentive to invest in R&D and new drugs would not be discovered. The case of natural monopoly discussed in section 9.10 and in concept 9.2 is important, so make sure you understand this and the issues of regulation that arise. In Figure 9.17, little would have been lost if the LMC curve were simply a horizontal line. This would correspond to a long-run total cost curve of the form TC = a + bQ where a is the fixed cost and b the constant marginal cost. Here the falling AC comes about as the fixed cost a is spread over larger outputs. Take the case of railways where there are large fixed costs in setting up the track network but the marginal cost per journey mile (Q) may be quite low in comparison. In this case it would be very inefficient to have several providers each installing their own parallel rail networks. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. Overview This block discussed the case of pure monopoly, where there is only one firm and large barriers to entry, such that the monopolist faces no competition from incumbent firms or even from potential entrants. The profit-maximising output for the monopolist is discussed, with the monopolist choosing the quantity where MC = MR. Price is higher than MR for the monopolist. Just how much higher it is depends on the elasticity of demand and indicates the degree of monopoly power for that industry. Where a monopolist and a perfectly competitive market can meaningfully be compared, a monopolist charges a higher price and supplies a lower quantity of output. The allocative inefficiency of monopoly is demonstrated by the loss of social surplus (called ‘deadweight loss’) compared to the case of perfect competition. 90 A discriminating monopolist charges different prices to different consumers. First-, second- and third-degree price discrimination are explained, including the impact on output, price and profits. These strategies transfer surplus from consumers to producers but reduce the deadweight loss of the monopolist. Despite the allocative inefficiency of monopoly, one possible advantage could be that monopoly profits provide an incentive for firms to innovate. Furthermore, there are some industries which work best as monopolies, these are called natural monopolies and have a falling long-run average cost curve over the whole range of production. These are generally industries with very large fixed costs such as water, electricity and telecommunications, and tend to be heavily regulated by government or publicly owned. Block 7: Pure monopoly Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the best response 1. A monopolist faces an (inverse) demand curve given by P = 100 – 2Q. Marginal cost is constant and equal to 16. Profit maximisation is achieved when price is equal to: a. 45 b. 21 c. 58 d. 82 2. A profit-maximising monopolist sets an output of 100 per day and a price of £20. Which of the following statements is true? a. The firm’s marginal cost and marginal revenue curves intersect at an output of 100, and the point on its demand curve at this output is at £20. b. The firm’s marginal cost and marginal revenue curves intersect at an output of 100, and the point on its marginal revenue curve at this output is at £10. c. The firm’s marginal cost and average revenue curves intersect at an output of 100, and the point on its marginal revenue curve at this output is at £20. d. The firm’s marginal cost and average revenue curves intersect at an output of 100, and the point on its average revenue curve at this output is at £20. 3. Assume that the demand for a new software is P(Q)=120–2Q. The cost of producing it is C(Q)=4Q for a monopolist. What is the deadweight loss associated with the monopoly in this market? a. 1,682 b. 1,566 c. 841 d. 775 True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Monopolies always imply deadweight losses in the market. 2. A monopoly is never desirable. 3. Monopolists can find the optimal price without knowing the full demand schedule. 91 EC1002 Introduction to economics Long response question 1. A monopolist faces a demand curve P = 120 – 54Q. The firm faces a constant marginal cost MC = 20. a. Calculate the profit-maximising monopoly quantity and price. Use the formula linking MR, P and MC to find price elasticity of demand at this point in the demand curve. b. Suppose that all firms in a perfectly competitive equilibrium had a constant marginal cost MC = 20. Find the long-run perfectly competitive industry price and quantity. c. Compare consumer surplus under monopoly versus perfect competition. You may find it useful to draw a diagram. d. What is the deadweight loss due to monopoly? Is this the same as the difference between the two consumer surpluses you calculated in c.? 92 Block 8: Market structure and imperfect competition Block 8: Market structure and imperfect competition Introduction Most firms in the real world do not operate within markets described by the textbook definitions of perfect competition or pure monopoly. This block introduces a theory of market structure and some models of imperfect competition. These models help to explain some of the phenomena we see in real world markets such as advertising, price wars and product differentiation. Game theory is introduced as a useful tool for analysing strategic interactions. The maths boxes show how to find reaction functions of firms competing with each other in a market structure called duopoly (where there are two firms). You will need to practise using these to calculate price, output, profits and consumer and producer welfare and compare these to the outcomes of other market structures such as monopoly and perfect competition. Although these look complicated, in fact, they are all based on the simple equations that: Profit = Total Revenue – Total Cost and Total Revenue = Price * Quantity. The formulas for marginal revenue and marginal cost can be derived from these using calculus. MR, in the case of linear demand, can also be derived using the result already seen that MR has the same intercept on the price axis and is twice as steep as the demand schedule. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • recognise imperfect competition, oligopoly and monopolistic competition • discuss how cost and demand affect market structure • interpret an N-firm concentration ratio • identify equilibrium in monopolistic competition • recognise the tension between collusion and competition in a cartel • describe game theory and strategic behaviour • identify dominant strategies • analyse simultaneous (one shot) games to find Nash equilibria • analyse sequential games using backwards induction • analyse reaction functions and Nash equilibrium • describe Cournot and Bertrand competition and the idea of Stackelberg leadership Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 10, except 10.6 and A10.2. 93 EC1002 Introduction to economics Synopsis of this block This block starts by introducing a theory of market structure, focusing on how market structure depends on the shape of the industry longrun average cost curve and the position of the market demand curve. Market structure can be described using an N-firm concentration ratio. Two specific types of imperfect competition are analysed in this block– monopolistic competition and oligopoly. One key characteristic of a monopolistically competitive market is product differentiation. The long-run equilibrium of this market is described graphically. One key characteristic of oligopoly is strategic interaction. Firms can either compete or collude. If they compete, this can be analysed using models from game theory, such as the prisoner’s dilemma. A specific example of oligopoly is duopoly, where there are only two firms. They can compete on output (Cournot behaviour) or price (Bertrand behaviour). If one firm moves first, it is a Stackelberg leader. The outcomes of these interactions are described in this block, and you will learn how to find these and how to compare them with the outcomes that arise under monopoly and under perfect competition. The behaviour of incumbents is affected not only by other firms already in the market, but also by the threat of entry of new firms. Barriers to entry can either be natural (innocent) or strategic (constructed). Strategic entry deterrence can consist of investing in spare capacity, in advertising, or in product differentiation, for example. This can be analysed by use of a decision tree. In all these games, the concept of Nash equilibrium is important and demonstrates a stable outcome, from which the players have no incentive to diverge. A theory of market structure ► BVFD: read the introduction and section 10.1 of Chapter 10. The crucial determinant of market structure is minimum efficient scale (the lowest point at which a firm’s LAC curve stops falling) relative to the size of the total market as shown by the demand curve. The concentration ratio measures the fraction of total output in an industry that is produced by some specific number of the industry’s largest firms. The N-firm concentration ratio leaves this number general. Once it has been specified, we refer to the five-firm concentration ratio, or threefirm concentration ratio, for example. The degree of competition in a market is also affected by globalisation – the closer integration of markets across countries – since this increases the ability of foreign producers to compete effectively in the domestic market. As such, the degree of competition does not only depend on the number of domestic producers alone. Activity SG8.1 1. Calculate the four-firm concentration ratio of an industry with the following distribution of sales: 40%, 10%, 10%, 10%, 8%, 8%, 6% 4% 2% 1% 1%. a. 100% b. 80% c. 70% d. 40%. 94 Block 8: Market structure and imperfect competition Monopolistic competition ► BVFD: read section 10.2. Monopolistic competition describes a market structure with a large number of firms, each one selling a product which is an imperfect substitute for the product of its rivals (this is called product differentiation). Each firm faces a downward sloping demand curve for its product. Firms in a monopolistically competitive industry are not price-takers; they have some market power and can set the price they charge. If they increase price they will lose some customers, but not all. If they drop their price they will gain some market share but will not capture the whole market. Since the number of firms is large, they can ignore any reactions of competitors when they make their output and pricing decisions. A further important assumption of this model is that there is free entry and exit. When a new firm enters the industry, it will take customers from all existing firms, shifting the demand curve faced by each firm to the left. The key element that makes monopolistic competition different to perfect competition is that firms face a downward sloping demand curve rather than a horizontal demand curve (i.e. demand for their products is not perfectly elastic as it is in perfect competition). Since this is due to product differentiation (the assumption that the goods are heterogeneous), firms have a strong incentive to advertise their products – either to inform customers about what makes their product different, or to create and enhance customers perceptions of this difference. If advertising is effective, it can increase the demand for a product and also decrease the elasticity of that demand, both of which can lead to an increase in revenue for the firm. Activity SG8.2 Figure 10.2 shows the short-run and long-run equilibria for a firm in a monopolistically competitive market. Remember that the demand curves DD and DD’ (and the associated MR curves) refer to a single firm in the market. The market demand curve, of course, lies further to the right. Practice drawing the diagram yourself, highlighting: i. the short-run monopoly profits ii. the tangency of the DD’ curve and the AC curve in long-run equilibrium. In the long run, the price charged by firms is equal to the average cost and they are just breaking even. In industries where there are many producers but of differentiated products, free entry will tend to eliminate profits in the long run. Monopolistic competition and efficiency The long-run equilibrium point is not on the minimum of the LAC curve as it would be under perfect competition – this implies inefficiency, as firms are operating with extra capacity, on the downward sloping section of their average cost curves. Any point on the LAC curve is by definition productive efficient. Producing on the downward sloping part of the AC curve implies a loss of allocative efficiency, as price will be higher than marginal cost (since the LMC curve passes through the lowest point of the LAC curve). Because the price is set higher than the marginal cost, consumer surplus is lower than it would be if prices were set equal to marginal cost at the lowest part of the firm’s AC curve. 95 EC1002 Introduction to economics Oligopoly ► BVFD: read section 10.3 (but not the kinked demand curve) An oligopoly is a market structure characterised by there being only a few firms, which interact strategically. Firms are aware that their decisions affect the actions of other firms and that their own optimal decisions depend on what the other firms are doing. The basic tension is between wanting to collaborate to achieve a monopoly outcome, and the incentives to cheat on any agreement so as to raise one’s own market share and profits. Examples of oligopolies in the UK include the supermarket industry (dominated by Tesco, Sainsbury and ASDA) and retail banking (dominated by Barclays, Lloyds, the Royal Bank of Scotland and HSBC). Oligopolistic industries tend to be dominated by a few large firms. One reason for this is that large firms often have a competitive advantage because their fixed costs (e.g. research and development) can be spread out over a greater sales volume so the per unit cost is reduced. A further reason is that large firms can exploit economies of scale and scope, which creates natural entry barriers. Economies of scale arise because a large scale facilitates the division of labour, which increases productivity. Economies of scope apply to firms that produce multiple products and arise because firms can share resources or functions between different product areas. In industries where there are large economies of scale or scope, there is simply not enough room for a large number of firms, all operating at or near their minimum efficient scales. Hence, it is more common for a small number of large firms to dominate the market. Profits under oligopoly In some oligopolistic industries, firms manage to approach joint profit maximisation (in this case, the outcome in terms of market price and output is similar to pure monopoly). In others, firms compete very intensely and approach the perfectly competitive output. In the long run, profits will attract entry, unless there are natural entry barriers such as large economies of scale. Game theory ► BVFD: read section 10.4. Considering the extent to which game theory has revolutionised much of modern industrial organisation theory, and oligopoly theory in particular, the treatment here in BVFD is relatively brief (although the treatment in this section is expanded in section 10.7). Game theory is a very useful approach for analysing strategic interaction. In a game, your best move depends on what your opponent does. This is helpful for analysing oligopoly, since one of the key features of this market structure is strategic interaction between firms. One key concept is a dominant strategy – a player has a dominant strategy if one strategy is their best response, regardless of what the other player does. In Figure 10.5, choosing a high output is a dominant strategy for each firm. Another key concept is Nash equilibrium – this is a situation where no player has an incentive to change their strategy, since they are doing as well as they can, given the strategies chosen by the other players. Note that in Figure 10.5 the Nash equilibrium is, unsurprisingly, the pair of dominant strategies. However, it is not necessary that both firms have a dominant strategy for there to be a Nash Equilibrium. 96 Block 8: Market structure and imperfect competition Activity SG8.3 You and your partner were just arrested for the burglary you pulled off last night, and are being interrogated separately in different rooms. The officer says to you ‘Well, looks like you’ve got some decisions to make here. You can confess to the burglary or you can continue to deny any role in it. Your problem is that the consequence for you depends on what your partner does. If he confesses and you don’t, we’ll throw the book at you and give him immunity. You get 10 years in jail and he goes free. Of course, the reverse would be true if you confess and he doesn’t. If you both confess, you’d both get a lighter sentence, 5 years. If you both insist on denying the charges, we should have enough evidence to get you both for 1 year for sure.’ Now answer the following questions: a. What does the payoff matrix for this game look like? (base this on Figure 10.5) (it is conventional to make the payoff for the player, on the left hand side of the payoff matrix, the ‘row player’, the first entry in each cell and the payoffs for the player at the top of the matrix, the ‘column player’ second). b. Does either player have a dominant strategy? c. Does this strategy result in the best joint outcome for the prisoners? d. Does this strategy result in the best outcome for the police? The game in Figure 10.5, and the traditional prisoner’s dilemma you have just worked through are one-off games (sometimes called ‘one shot’ games). Many real-world economic decisions, such as firms setting prices or quantities, relate to repeated actions rather than one off moves. This can quite dramatically change the expected outcomes. The intuition is that repeated games provide incentives for cooperation that are absent in one-off games; in a repeated game, honest behaviour can be rewarded and cheating can be punished (it is necessary that the threat of punishment is a credible threat). Models of oligopoly ► BVFD: read section 10.5 and Maths A10.1. This section covers models of oligopoly (illustrated in the two-firm case, a duopoly) that preceded game theory by many years (Cournot and Bertrand were 19th-century French mathematical economists and Stackelberg, a German economist, first published his analysis in 1934). While it is often possible to reformulate the models in game theoretic terms, it is instructive to understand the structure of such models. We will cover the Cournot and Bertrand models formally in this subject guide and the idea behind Stackelberg leadership, but will not cover the mathematics of the Stackelberg model. The Stackelberg model as described in A10.2 is not examinable. Cournot model The graphical analysis of the Cournot model is useful if you find the mathematics in Maths A10.1 difficult. If you don’t, the mathematical treatment is more concise. Note that Maths A10.1 uses calculus in deriving the reaction functions. But in the last chapter, we showed that for a linear demand curve the MR curve has the same intercept on the price axis, but is twice as steep. Let us see how this works out in the example BVFD use in the maths box. 97 EC1002 Introduction to economics We are given the market demand curve P = a – bQ, which we can write as P = a – bQA – bQB. Now we want to write firm As MR curve as a function of its own output, holding its rival’s output constant, so using the result from the last chapter, MRA= a – 2bQA – bQB . Although calculus is the most straightforward means, there is an alternative method of finding MC. Using delta notation as before, ∆TCA = c∆QA. Therefore: ∆TC MC = c = A ∆QA Now setting MRA = MCA gives us A’s reaction function and similarly for firm B. Solve the two reaction functions simultaneously to get the Nash equilibrium in quantities. Firm A’s reaction function can be expressed as: a–C a–QB QA = – 2b 2 Firm B’s reaction function can be similarly derived and is symmetric since both firms are assumed to have the same marginal cost. Hence: QB = a–C 2b – a–QB 2 Solving simultaneously (or setting QA=QB and solving, in light of symmetry) gives the Cournot quantities are: a–c QA = Q B = 3b Total supply is higher than in a monopoly. The corresponding market price is: a+2c P= 3 Activity SG8.4 Consider a market for a homogeneous product with demand given by Q = 37.5 – P/4. There are two firms, each with a constant marginal cost equal to 40. a. Determine output and price under a Cournot equilibrium. b. Compute the deadweight loss as a percentage of the deadweight loss under a nondiscriminating monopolist. Activity SG8.5 Which model of strategic duopoly interaction (Cournot or Bertrand) would you think provides a better approximation to each of the following industries, and why? i. oil refining ii. insurance. Sequential games ► BVFD: read section 10.7. The game discussed in this section is represented again below with an alternative presentation of the payoffs, for clarity. Sequential games such as this are often represented with the payoffs at the end of the relevant path. As stated below the diagram, in each case the first payoff in each 98 Block 8: Market structure and imperfect competition set of brackets is the incumbent’s, the second the potential entrant’s. This depiction, and that in Figure 10.11, is known as the extensive form of the game (sometimes also known as a decision tree). Without strategic entry deterrence With strategic entry deterrence Entrant Entrant In In Out Incumbent Accept (1,1) Accept Fight (-1,-2) (5,0) Out Incumbent (-2,1) Fight (-1,-1) (2,0) Payoffs are: (Incumbent, Entrant) Figure 8.1: Strategic entry deterrence. Let us start with the case where there has been no strategic entry deterrence, for example there has been no investment in excess capacity which can be used to quickly flood the market with extra output. This is shown as the game on the left above, and in the top row in the matrix in Figure 10.11. Sequential games can be solved by backwards induction, which means starting from the final step of the game. In this case, only one leg of the decision tree involves a decision by the incumbent (i.e. the left leg). The incumbent can either choose between a payoff of 1 (if it accepts the entry without fighting) or –1 (if it fights). It will choose 1. The threat to fight entry is not a credible one in this case. Now going back to the first step of the game, where the entrant has a decision to make. The entrant can either choose a payoff of 1 (if it enters, since it knows the best move for the incumbent will be to accept its entry) or 0 (if it does not enter). It chooses 1. The outcome of the game is thus that the entrant enters and the incumbent accepts. Both make a profit of 1. Now for the case where the incumbent has taken steps to deter entry – the game on the right (the second row in Figure 10.11). As described in the textbook, this could be by investing in spare capacity which is only useful if it chooses to fight a market entrant. Starting again with the second part of the game, the incumbent chooses between a payoff of –2 (if it accepts) and –1 (if it fights). It will choose –1. The entrant thus faces the following choice: a payoff of –1 (if it enters and the incumbent fights), or a payoff of 0 (if it doesn’t enter). It will choose 0. Thus, the outcome of the game is that the entrant does not enter and the incumbent makes a profit of 2. As compared to the first case (no spare capacity) the incumbent’s threat to fight is credible, it does better by fighting than by accepting. Sequential games and backward induction are useful tools for analysing this type of market interaction. However, certain key assumptions are required, for example that both players have accurate knowledge of the whole decision tree, including the payoffs of their opponent. An interesting sequential game is the Stackelberg model (analysed mathematically in A10.2, but not examinable). Unlike in Cournot competition where firms choose their output level simultaneously, in the Stackelberg model they choose their output sequentially. There is a leader 99 EC1002 Introduction to economics who moves first and a follow who sets output section. The key insight of the Stackelberg model is that there is a first mover advantage – in the Stackelberg equilibrium the leader reaps higher payoffs than in Cournot competition, while the follower reaps lower profits than in Cournot competition. ► BVFD: read section 10.8 and the summary, and work through the review questions. Overview Market structure is partly determined by firms’ minimum efficient scale (the lowest point at which a firm’s LAC curve stops falling) relative to the size of the total market as shown by the demand curve. Imperfect competition exists when firms face a downward sloping demand curve. The most important forms of imperfect competition are monopolistic competition, oligopoly and pure monopoly. The key characteristic of a monopolistically competitive market is product differentiation, which gives each firm some limited monopoly power in its special brand. There is free entry and exit. In long-run equilibrium, the demand curve is tangent to the firm’s LAC curve, and price is equal to average cost but is greater than marginal cost and marginal revenue. The key characteristic of oligopoly is strategic interaction. Strategic interaction can be analysed using game theory. The outcome will depend on whether the game is played once or repeatedly, and if it is possible for firms to make binding commitments. A specific example of oligopoly is duopoly, where there are only two firms. In a Cournot duopoly, each firm treats the other firm’s output as given. Whereas in a Bertrand duopoly, each firm treats the other firm’s price as given. If instead one firm moves first and sets output, that firm is a Stackelberg leader and will gain higher payoffs than the firm which follows. The outcomes of these forms of interaction can be compared with the outcomes that arise under monopoly and under perfect competition. In some oligopolistic industries, firms manage to approach joint profit maximisation (in this case, the outcome in terms of market price and output is similar to pure monopoly). In others, firms compete very intensely and approach the perfectly competitive output. In the long run, profits will attract new firms into the industry unless there are barriers to entry. The analysis of imperfect competition helps explain real world phenomena such as advertising, price wars and product differentiation. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the best response. 1. Refer to the box below. Two bus companies offer a daily service Two firms, A and B, produce the same product and compete by setting prices. They are the only firms that produce the product. Both firms have a marginal and average cost of £2. If both firms set the same price, they share the market equally. If they charge different prices, the firm charging the lower price takes the entire market. Which of the following statements is incorrect? 100 Block 8: Market structure and imperfect competition a. The equilibrium price is equal to marginal cost. b. In equilibrium both firms set the same price. c. In equilibrium the two firms share the market equally. d. Because the number of firms in the industry is small firms make profits in equilibrium. 2. An industry is a Cournot duopoly with two firms A and B. Industry inverse demand is p = 10 – Q, where Q = qA+qB. Both firms produce with a constant average and marginal cost 4. Which of the following statements is correct? qB a. Firm A has a reaction function QA = 3 2 b. Both firms produce 3. c. The industry price is 5. d. Both firms make losses. 3. Suppose both England and Norway fish in the North Sea. Both countries know that their fish supplies are being depleted and that this depletion could be slowed down if they both cut their fishing fleets in half. The matrix below shows the payoff for both countries (England’s payoff is first entry in each cell) with unchanged and halved fleets. Norway England 10 boats 5 boats 10 boats 300,300 550,250 5 boats 250,550 500,500 a. There is no Nash equilibrium. b. There is a Nash equilibrium where England and Norway both employ five boats. c. There are two symmetric Nash equilibria where one country employs five boats and the other 10 boats. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. If the market consists of only two producers that compete in prices and have the same production costs, then equilibrium output is the same as if the market was perfectly competitive. 2. In a tennis game Serena is playing against Naomi. Serena and Naomi each choose between two actions: to play more in the front or in the back. If they both make the same choice, Serena wins. If they make different choices, Naomi wins. In this game there are no pairs of actions that are best responses to each other. 3. If two players have a dominant strategy, then there will not be any other Nash equilibria than the outcome in which both players play their dominant strategy. Long response question 1. a.People generally believe that oligopolies (and in particular duopolies) are always inefficient. Are they correct? b. Two firms A and B produce the same good. Each sets the price of the good. If the two firms set the same price, they share the market equally. The demand for the output of the industry is Q = 90 – p where p is the price. Both firms have a marginal and average cost 101 EC1002 Introduction to economics of £10. The two firms observe that they can both increase profits if they set up a cartel which produces the level of industry output which maximises industry profits. What is the output of the cartel? What is the industry price? Assume that the two firms share the market equally. What profit does each firm make? c. Suppose firm B believes that firm A will remain at its cartel level of output. What is the profit maximising level of output for firm B? d. Under what conditions is it difficult for firms to sustain a cartel? Food for thought – Box 2: Should wages be fair? When analysing individual labour market decisions we assume that people decide how many hours to work based on the wage rate and their preferences over leisure and consumption. In this model, the wage drives the decision to work (and the hours of work chosen) by becoming the opportunity cost of spending time in leisure. Economists have questioned the assumptions behind this result. Some have picked at the fact that not all people are able to choose their hours of work – it is much more common for people to say yes or no to a contract including a fixed amount of hours, or to choose to go full or part time. Others have pointed to the fact that people derive job satisfaction and so the notion of work as a source of disutility that needs to be compensated for through a wage is oversimplified. These critiques, however, do not consider how the wage could influence the quality of work. In 1990 George Akerlof and Janet Yellen introduced a new model to try and explain how workers decide the effort to put in their activity, moving the discussion forward by thinking about workers’ behaviour after choosing the hours of work. Their hypothesis, motivated by equity theory in social psychology and social exchange theory in sociology, states that workers are motivated by their pay and that the wage influences the effort exerted (i.e. the quality of work) in a given task. The motivation for the fair wage-effort hypothesis is the observation that people who feel that they are not getting what they deserve try to get even! In this model, people form an idea of a wage they deem ‘fair’ for a given task. If they are paid this fair wage, they exert maximum effort in their tasks. But if the actual wage falls short of their perceived fair wage, then workers proportionately withdraw effort. Unemployment thus occurs when the fair wage exceeds the market-clearing wage. This hypothesis is consistent with observed data on wage differentials and unemployment patterns. Try and think about what you would deem a fair wage for different tasks. What motivates an increase in your perceived fair wage? Do you think other people would state the same numbers? From Akerlof and Yellen (1990) citing Mathewson (1969): I am working with the feeling That the company is stealing Fifty pennies from my pocket every day; But for ever single pennie [sic] They will lose ten times as many By the speed that I’m producing, I dare say. For it makes one so disgusted That my speed shall be adjusted 102 Block 8: Market structure and imperfect competition So that nevermore my brow will drip with sweat; When they’re in an awful hurry Someone else can rush and worry Till an increase in my wages do I get. No malicious thoughts I harbor For the butcher or the barber Who get eighty cents an hour from the start. Nearly three years I’ve been working Like a fool, but now I’m shirking— When I get what’s fair, I’ll always do my part. Someone else can run their races Till I’m on an equal basis With the ones who learned the trade by mining coal. Though I can do the work, it’s funny New men can get the money And I cannot get the same to save my soul. [Mathewson, 1969, p.127]. 103 EC1002 Introduction to economics Notes 104 Block 9: The labour market Block 9: The labour market Introduction The previous blocks discussed the theory of the firm and various market structures. Part of the theory of the firm is the way in which firms aim to combine inputs in the most cost efficient way possible. This gave us the first taste of the roles of capital and labour in the production process. In addition to labour and capital, the factors of production also include land and raw materials, as well as entrepreneurship. These factors will be briefly explained below. This block then focuses on the labour market. Some of what you will learn about the labour market is also relevant for the analysis of the other factors of production; however, there are also key differences. We will not explore these further in this block. Interested students can read BVFD Chapter 11 – otherwise, you will most likely cover the analysis of markets for the other factors of production in later years as you continue your studies in economics. The study of the labour market is important – not least from an individual point of view, as most of us will allocate a substantial fraction of our time to the labour market in the future (if you are not already doing so). Furthermore, many social policy issues concern the labour market experiences of particular groups of workers. Finally, as we have already mentioned, labour is a key input in the production process. The overall productivity of an economy depends on the skills of the labour force and the quality of management. It also depends on the level and nature of the capital stock. The approach to this subject matter is similar to the analysis of markets for consumer goods, and the structure of the textbook chapter will also be familiar to you (covering demand, supply, equilibrium, and adjustments). However, in some ways the details are quite different. For example, labour is human effort, thus the supply of labour depends on individual preferences. In this course, the labour that firms buy is modelled in essentially the same way as renting a machine. Decisions on how much labour households supply is treated as the other side of the decision about how much time to spend not working for money, which is referred to as leisure. There are useful things to be learnt from this simple model, although the idea that time spent not working for money should be called leisure is nonsense to anyone with caring responsibilities for children and other family members. Economists have thought about these things, but they are not an important part of most introductory and intermediate level courses in microeconomics. From moral, political and economic viewpoints, people are in fundamental ways not the same as machines. The ways in which people working in organisations do or do not have power and status, and the ways in which the organisation manages and motivates its people, are fundamentally important to those involved and the way the organisation works. This depends partly, but only partly, on how much people are paid. Economists are increasingly interested in the incentives within organisations, the way in which pay is related to hours worked, to measurable outcomes, and to outcomes that cannot easily be measured. Work is also very important for people’s sense of themselves – losing your job or being unable to find a job are major risk factors for depression. The course EC3015 Economics of labour covers some of these issues. 105 EC1002 Introduction to economics Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • describe the factors of production • analyse a firm’s demand for inputs in the long run and short run • recognise marginal value product, marginal revenue product and marginal cost of a factor • define the industry demand for labour • analyse labour supply decisions • define economic rent • define labour market equilibrium and disequilibrium • demonstrate how minimum wages affect unemployment. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD) Chapter 11 (except 11.8). Synopsis of this block This block first introduces the factors of production and then provides an analysis of the firm’s demand for factors, building on the analysis from the Block 5 on the firm, where the firm’s choice of a cost-minimising mix of inputs was discussed. Having now analysed various market structures (Blocks 6–8), the impact of the shape of the demand curve the firm faces for their output on their demand for inputs (which is derived demand) is now clarified, focusing on labour. The more elastic the firm’s demand and marginal revenue curves, the more an increase in the price of labour leads to a fall in the firm’s demand for labour. In the short run, at least one factor of production is fixed, but the firm can adjust its variable input which is labour. Labour is subject to diminishing marginal returns when other factors are fixed and the marginal physical product of labour falls as more labour is hired. The firm hires labour until the marginal cost of labour equals its marginal revenue product. The industry’s demand for labour is less elastic than the horizontal sum of firm’s short-run demand curves, because higher industry output in response to a wage reduction also reduces the output price. In terms of the supply of labour, this depends on the size of the population, the participation rate and the number of hours people choose to work. For someone already in the labour force, a rise in the hourly real wage has both a substitution effect tending to increase the hours worked and an income effect tending to reduce the supply of hours worked. Four factors increase the participation rate: higher real wages, lower fixed costs of working, lower non-labour income and changes in tastes in favour of working. The industry supply curve of labour depends on the wage paid relative to wages in other industries using similar skills. People who would like to work and are actively seeking work but cannot find a job are unemployed. Unemployment can be defined as voluntary or involuntary. Possible causes of involuntary unemployment (representing disequilibrium in the labour market) are minimum wage agreements, trade unions, scale economies, inside–outsider distinctions and efficiency wages. 106 Block 9: The labour market The factors of production The production of any good or service requires inputs. These are known as the factors of production. The three main inputs to the production process are: land, labour and physical capital. • Land comprises all free gifts of nature such as land, forests, minerals etc. Although its productivity can be improved through fertiliser and irrigation (for example), its supply is generally considered fixed, even in the long run. • Labour includes the mental and physical effort of people employed in return for remuneration. Each individual has different skills, qualities and qualifications. This is known as their human capital. • Physical capital is the stock of produced goods that are used in the production of other goods and services by firms (mostly) and also households. Physical capital is manufactured, which means that the stock of capital can be increased. It is not completely consumed in the production process although it does tend to wear down over time – this is known as depreciation. Supplied by Consumed in production? Speed of adjustment Land Nature No Never – fixed supply Labour Individual people No Fast Capital Firms (generally) Not fully Medium Table 9.1: Characteristics of key factors of production. These are the three main inputs to production described in BVFD. Other textbooks add further inputs, for example: raw materials and entrepreneurship. • Raw materials are also provided by nature and are included together with land in many definitions; however one key difference is that raw materials (such as oil, coal, cotton, etc.) are fully consumed in the production process. Thus in one sense, there is little difference between the analysis of markets for raw materials and markets for final consumption goods. • Entrepreneurship is provided by entrepreneurs or innovators and includes introducing new ideas and business practices as well as accepting risk to their own resources and possibly also organising the other factors of production. Analysis of the labour market ► BVFD: read Chapter 11. One key difference between our analysis of consumption goods in the previous blocks and our analysis of labour as an input to production in this block is that the roles of the key market participants have been reversed. Previously, when we talked about consumption goods, firms were the suppliers and individuals were the consumers. In the labour market, individuals are now supplying their labour, which firms demand. A second key difference is that the demand for labour is derived demand, in that the demand for labour depends on the demand for the goods produced by that labour. Firms’ decisions on how much to produce and how to produce it imply specific demands for various quantities of inputs. 107 EC1002 Introduction to economics Labour demand in the long run ► BVFD: read section 11.4 and Maths 11.1. When analysing input markets it is important to distinguish between the short run, when (by definition) the amount of at least one input cannot be varied by the firm, and the long run, in which the firm is free to vary all its inputs. This section deals with the labour market in the long run. Because both labour and capital can be varied, an increase in the price of labour (the wage rate) will decrease the demand for labour due both to the substitution effect (capital becomes relatively cheaper so any given output is produced more capital-intensively) and the output effect (with higher costs, the profit maximising output level, where MC = MR, falls). The point made in Figure 11.1 is returned to below in the discussion of the short-run demand for labour. This section (BVFD Section 11.1) goes beyond the analysis in Chapter 8 to demonstrate how the elasticity of demand impacts on the output effect of a change in one of the factor prices. The (perfectly elastic) horizontal demand curve DD is much more elastic than the downward sloping demand curve D’D’. If the firm faces the less elastic curve, the output effect of an increase in costs is smaller – as can be seen in Figure 11.1. This shows the importance of recognising that the demand for factors is derived demand such that the characteristics of the demand for the output have an impact on the demand for the factors of production. Activity SG9.1 Use budget constraints and indifference curves to demonstrate the effect on the demand for labour of a fall in the wage rate – clearly indicate both substitution and output effects and accompany your graphs with a written explanation. Activity SG9.2 A fall in the wage rate will: a. increase the demand for capital but the effect on the demand for labour is uncertain b. increase the demand for labour but the effect on the demand for capital is uncertain c. decrease the demand for capital but the effect on the demand for labour is uncertain d. decrease the demand for labour but the effect on the demand for capital is uncertain. Short-run demand for labour ► BVFD: read section 11.2 and Maths A11.1 and Case 11.1. The firm can calculate the optimal amount of capital and labour to use as inputs in the production process using marginal analysis: the extra value gained from one more unit of the input must be equal to the unit price of that input. The extra value gained from one more unit of the input is, in turn, the marginal physical product of the input multiplied by how much the firm gets, per unit, from selling that extra output. In the case of a price taking firm, and section 11.2 only considers competitive firms, the marginal physical product is just multiplied by the price of output, which is of course constant for the firm. In the case of a firm facing a downward sloping demand curve for its product, a monopolist for example, we cannot just multiply MPL by the original product price to get the monetary value to the firm of the extra output. Why not? Because to sell more 108 Block 9: The labour market output the price will have to fall, not just for the marginal unit but for all units. If you don’t remember why this is, revise the monopoly block and chapter. When the demand curve is downward sloping the optimal rule for hiring an input is, in the case of labour, to hire labour until the wage is equal to the marginal revenue product of labour (MRPL)1, i.e. until W = MRPL = MRQ * MPL where MRQ is the marginal revenue that the firm gets from selling an extra unit of output. Recalling from Block 7 that: 1 ε ( ( MRQ = P 1 + where ε is the price elasticity of demand for output, the hiring rule becomes to higher labour up to the point where: 1 .MPL ε ( ( W=P 1+ In the case of perfect competition where ε is minus infinity, just reduces to W = P * MPL, or W = MVPL in the textbook. Note that because ε is negative, the labour demand curve for a non-competitive firm lies below the labour demand curve for a competitive firm with the same MPL curve and is steeper. As in Figure 11.1, output, and hence the derived demand for labour, is less responsive to wage changes the less elastic is the demand for output.2 Activity SG9.3 Imagine you are the manager of a small firm which makes and sells doughnuts and you need to decide how many workers to employ. Use the information below to make your decision. A doughnut sells for £1.50. All workers work an eight-hour shift and the wage rate given is the hourly rate. The market for doughnuts is perfectly competitive. Explain the reasoning behind your decision. MPL Some textbooks using the term marginal revenue product for both competitive and non-competitive firms, others, such as BVFD, reserve the term MVPL for the competitive case where MR=P. 1 Workers Output per hour MVPL(£) 1 20 7 2 30 7 3 37 7 4 42 7 5 44 7 This is the basis for one of the Hicks-Marshall laws of derived demand: other things equal the elasticity of labour demand with respect to the wage is high when the price elasticity of demand for output is high. 2 Wage rate (£) Industry demand curve for labour ► BVFD: read section 11.3. As explained in this short section and the accompanying diagram, the industry demand curve for labour is steeper than the industry MVPL schedule, the horizontal addition of the original MVPL curves of each firm in the industry, since a lower wage increases industry output, leading to a fall in equilibrium price and a shift in the MVPL schedule. The industry demand curve for labour connects points on multiple MVPL schedules. The slope of the labour demand curve reflects the elasticity of demand for the product being produced, since demand for labour is derived demand, depending on demand for the output. 109 EC1002 Introduction to economics Labour supply ► BVFD: read section 10.4 and Maths 10.2, as well as case 10.1. This section applies the theory of consumer choice to an individual’s decisions of how to allocate their time between hours of leisure and hours of paid work3 for individuals who are in the labour force as well as the decision about whether or not to participate in paid work in the first place. You should treat Maths 11.1 as an integral part of this section, not an optional extra. In fact, even the diagrammatic treatment in Maths 11.1 does not go far enough in that, although it indicates whether the income or substitution effect dominates for a given wage change, it does not show these effects separately in the first diagram of the Maths box. You are now asked to remedy this shortcoming by drawing for yourself a choice diagram which does show the separate income and substitution effects. In this basic model these are the only uses of an individual’s time. The model can be extended/modified to incorporate other important uses of time such as unpaid work in the home. 3 Activity SG9.4 Draw a large diagram showing a budget constraint and indifference curve for three different wage levels, such that it can be used to derive a backwards-bending labour supply curve. For each of the two increases in the wage level, clearly indicate the income and substitution effects, noting which is larger in each case (you may need to refer back to Figure 5.14 in Chapter 5 to remember how income and substitution effects can be distinguished graphically). This section of the text assumes that leisure is a normal good4, more of it will be consumed as real income increases. This is likely to be a realistic assumption, in practice, for most people. However, suppose that leisure is, in fact, an inferior good. How would this change the analysis of income versus substitution effects? Could there be a backward bending labour supply curve in such circumstances? Participation rates One important concept from this section is the reservation wage – the lowest wage a worker is willing to accept to work in a given occupation. For this section, pay attention to the way that the four main factors which increase participation are represented graphically, as per Figure 11.6. Activity SG9.5 Match the factor which increases participation to the description of the graphical representation of this factor in Figure 11.6. 110 Higher real hourly wage rate Shorter distance AC Lower fixed costs of working Shorter distance BC Lower non-labour income Flatter indifference curves Changes in tastes in favour of more work and less leisure Steeper budget constraint line In fact they make the even stronger claim that leisure is probably a luxury good. Remind yourself of the distinction between a normal and a luxury good (Block 3 – BVFD section 4.6). 4 Block 9: The labour market Supply of labour to an industry As is mentioned in this section, the supply of certain types of labour to the economy as a whole is relatively fixed in the short run. In the long run, population growth and education and training can increase the supply. How elastic the supply of a certain type of labour is to a particular industry depends in part on how large that industry is relative to the economy as a whole. Labour market equilibrium ► BVFD: read section 11.5 and case 11.2 as well as concept 11.1. Labour mobility The extent of labour mobility into and out of an industry affects the slope of the industry’s labour supply curve and the extent to which this curve shifts when there is a change in wages in other industries. When there is a high degree of labour mobility, wage increases in one industry easily flow over into other industries. Labour mobility is a crucially important determinant of a country’s economic efficiency, both in static terms, ensuring labour is allocated to its most productive uses and in dynamic terms, facilitating the emergence of new activities and industries while allowing for the orderly decline of some existing activities and industries where output demand is falling. Geographic mobility, and in particular international migration, is perhaps the most important dimension of labour mobility, but occupational mobility, the ability of workers to undertake new tasks in an ever-changing economy is also important for efficiency and growth. Labour mobility is a subject which has attracted increasing attention, both politically and in terms of economic research, in recent years, but is perhaps too much of a specialised topic for an introductory course and is more typically reserved for specialised courses in labour economics. However, a bit of basic supply and demand analysis can help us to see that some of the more extreme positions taken on international migration are likely to be misleading. Below we show the market for a particular type of labour, it could be nurses, builders, etc. Let us take the latter case. Wage Domestic supply W1 Total supply W2 Demand N3 N1 N2 Employment Figure 9.1: International migration and labour supply. 111 EC1002 Introduction to economics If only domestic builders supply the market, N1 will be employed and the wage will be W1. Suppose now that there is immigration of builders shifting the total supply outwards (and possibly, as in the diagram, making it more elastic). Employment increases to N2 and the wage falls to W2. We see that immigrant builders do not displace domestic builders on a 1 for 1 basis (as some crude views of immigrant labour would have us believe). N2–N1 immigrant builders are employed, while the employment of domestic builders falls by the smaller amount N1–N3. It is equally wrong of course to say that building wouldn’t get done at all without immigrant builders. Without the immigrant builders, the higher wages of builders leads to a fall in the amount of building that gets done, but there is, again, equilibrium in the market for building and builders. Monopsony A single purchaser in any market is called a monopsonist. When an employer is a monopsonist, workers must either accept the wage offered, or move to a different market. The analysis of monopsony in the labour market is, in effect, the mirror image of the monopoly analysis of a firm in the product market. The labour supply curve is upward sloping, since more workers will be willing to work when the wage is higher. The upward sloping labour supply curve represents the average cost curve of labour for the monopsonist. The marginal cost of labour lies above this curve, because if a non-discriminating monopsonist hirers one more worker, they must also pay the higher wage to all the workers who are already employed. The monopsonist is aware that by hiring more workers, it is increasing the price of labour – as such, it will hire fewer workers than under a competitive market structure. The employment decision of a firm with monopoly power in its output market has been dealt with above, where the rule to hire labour up until W = P 1 + 1 .MPL was discussed. ε ( ( ► BVFD: read section 11.6 and case 11.3. Many of the concepts in this chapter are analogous to concepts from the general demand and supply analysis of Chapter 3. For example, economic rent – payment to a worker in excess of their reservation wage – is analogous to producer surplus and is represented graphically by the area above the labour supply curve and below the equilibrium wage. The diagram (Figure 11.10) presented in the section refers to the market but, of course, some individuals with reservation wages well below the market wage of W0 can earn very substantial economic rents. Disequilibrium in the labour market ► BVFD: read section 11.7 and concept 11.2. This section introduces five reasons why labour markets may not clear – minimum wage laws, trade unions, scale economies, the insider–outsider dichotomy, and efficiency wages. If wages are fully flexible, they will be able to rise and fall to the equilibrium level where demand and supply are equated and the labour market clears. These five factors provide an explanation why wage levels may stay above the equilibrium rate, leading to some of the labour force being unemployed. There is something of a semantic issue involved in the use of the market clearing concept here. What is really meant by a non-clearing market in this section is that the equilibrium wage is above the competitive wage. Nevertheless, it could be argued that in each of these cases the market does in fact clear, subject to 112 Block 9: The labour market the institutions in place at the time. Take the case of the minimum wage in Figure 11.11. The minimum wage essentially rules out that part of the labour supply curve below W2. Although some workers would be prepared to work at W < W2, the law of the land does not permit firms to employ them at these wages, so the supply curve is essentially horizontal at W2 until it hits the supply curve at L = L2. Firms wanting to hire labour in excess of L2 will have to pay above the minimum wage. So one could say that the market clears where this modified supply curve intersects the demand curve (at L = L1). In concept 11.2 this is the argument used. The case of efficiency wages is another example where it is not really clear that this is a disequilibrium situation. Firms pay above a market clearing wage but get higher productivity as a result. Workers may collectively accept a slightly lower probability of employment as a price worth paying for the higher wages under such arrangements. Incidentally, one of the most famous historical cases of efficiency wages is the case of the Ford Motor Company just over 100 years ago. In 1913 the daily wage at the company was $2.50. Turnover and absenteeism were high but there was a plentiful supply of workers willing to work at that wage. Then, at the beginning of 1914 Henry Ford doubled the daily rate to $5 (for workers who had been with the company for at least six months) as well as shortening the working day. Workers queued outside Ford factories for employment on the new terms. Quit rates, absentee rates and firing rates fell dramatically; productivity increased and company profitability did not suffer in spite of this huge pay rise. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. Overview The three main factors of production are labour, capital and land. Labour includes all forms of effort supplied by people to those who employ them for monetary remuneration. Physical capital is the stock of produced goods that are used in the production of other goods and services. Land comprises all free gifts of nature such as land, forests, minerals etc. Firms choose a production technique to minimise the cost of producing a particular output level. By considering each level of output, they can construct a total cost curve. Factor demand curves are derived demands. A shift in the output demand curve for the industry will shift the derived factor demand curve in the same direction. A firm will hire a variable factor until its marginal cost equals its marginal value product (or marginal revenue product in the case of a firm which is not a price taker). A rise in the price of a factor reduces the quantity demanded of that factor due to both substitution and output effects. A rise in the price of another factor leads to an increase in demand due to the substitution effect and a decrease in demand for that factor due to the output effect. It is unclear which of these effects will dominate. The supply of labour depends in part on the decisions of individuals to participate in the labour force and also on the number of hours they choose to supply. Four things raise the participation rate in the labour force: higher real wage rates, lower fixed costs of working, lower nonlabour income and changes in tastes in favour of working. Higher wages impact on the hours of work decision through both a substitution effect, tending to increase the supply of hours worked, and an income effect, which at high wage levels tends to reduce the supply of hours worked. This leads to the labour-supply curve being backward bending. The 113 EC1002 Introduction to economics industry supply curve of labour depends on the wage paid relative to wages in other industries using similar skills. Workers in unpleasant jobs are often paid compensating wage differentials. Workers earning above their reservation wage are said to be earning economic rent. The wage is the rental price of labour but certain factors may lead to wage levels being above the equilibrium level, leading to unemployment in the labour market. These factors include minimum wage agreements, trade unions, scale economies, insider–outsider distinctions and efficiency wages. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response. 1. A profit maximising firm will employ labour up to the point where: a. Marginal revenue = marginal product. b. Marginal cost = marginal product. c. Marginal revenue product = average cost of labour. d. Marginal revenue product = marginal cost of labour. 2. The labour supply curve: a. is always upward sloping b. is always downward sloping c. slopes upwards when the substitution effect dominates d. slopes upwards when the income effect dominates. 3. Which of the following could explain a decrease in the demand for labour in a particular job? a. additional training that increases the productivity of each unit of labour in this market b. an increase in the amount of risk associated with this job c. a decrease in the amount of risk associated with this job d. a decrease in the productivity of each unit of labour in this market. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. A fall in the rental rate of capital will always lead to a decrease in the labour employed by a firm. 2. Parvati, who recently received a pay rise, committed to more hours of work than last year. Hence, she must consider labour as an inferior good. 3. The engineering industry has a high degree of labour mobility. Hence, provided they have the technical skills needed for the job, engineers will easily flow to industries that offer a higher wage than the industry in which they currently work. 114 Block 9: The labour market Long response questions 1. a.Describe the impact of a change in the hourly wage on a person’s labour supply decision, regarding both hours of work and their participation decision. b. Alisha earns £20 per hour for up to eight hours of work per day and is paid £25 for every hour in excess of this. She receives £20 per day from the government in child benefit (regardless of whether or not she works) and pays £8 per hour for childcare for each hour she works. If she works, she pays £5 per day for an allday bus ticket. Graph Alisha’s budget line, for an 18-hour day. c. Give some reasons why labour markets may not clear, illustrating with diagrams as much as possible. 115 EC1002 Introduction to economics Notes 116 Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government Introduction Blocks 10 and 11 are about the role of government in the economy seen from the perspective of microeconomics. The rest of the subject guide is largely about the role of the government seen from the perspective of macroeconomics. Questions of what the role of government should be are extremely important. They usually involve economics, but also involve moral and political issues well beyond economics. At the start of the book in Chapter 1.5, BVFD explains the distinction between positive and normative economics. ‘In positive economics, we aim to work as detached scientists. Whatever our political sympathy or ethical code we examine how the world actually works.... Normative economics is based on subjective value judgements, not on the search for any objective truth…’ There are substantial disagreements over how the world works, particularly on the rate at which prices adjust to their market clearing level. The different views have implications for public policy. BVFD Chapter 2.10 discusses some popular criticisms of economics and economists, including the point that economists disagree about important things. This is more of an issue for macroeconomics than microeconomics. This is in large part because it is in some ways easier to do empirical work on microeconomics and it is easier to make comparisons across different time and places when looking at only part of the economy. Blocks 11 and 12 discuss what microeconomics has to say on public policy, much of it organized around the question as to when markets work well and when they work badly. Markets do a remarkable job in coordinating a huge number of decisions. Very few people believe that governments should try to suppress all markets and work with an entirely planned economy as was attempted in the Soviet Union. Indeed it is impossible to suppress markets altogether, and markets cannot in practice be suppressed entirely by making them illegal when there are large profits to be made. Conversely few people believe that there should be no role for government in the economy; even the most pro-market people usually believe that there is a role for government in the legal system and national defence. Other people believe there should be a much wider role for government. What does microeconomics have to say on this? There are a number of questions: • Are there prices at which all markets clear, that is supply and demand are equal in all markets? In the diagrams you are familiar with there are always supply and demand curves that intersect giving market clearing price and quantity. The difficulty is that supply and demand in one market depends on prices in other markets – this is what general equilibrium as opposed to partial equilibrium is about. Imagine that the market for cars fails to clear – demand exceeds supply so there is some form of rationing. If the price of cars increases to a level that clears the car market this has an effect on the demand for petrol, so the price of petrol has to change – but then demand for the machinery use in oil refineries for turning crude oil into petrol changes and so on, and so on. It was established in the 1950’s by Arrow and Debreu that in the general competitive model of perfect competition there is an 117 EC1002 Introduction to economics equilibrium, that is, a set of prices at which all markets clear. Proving this required the use of some very sophisticated mathematics. • Are markets efficient? The concept of efficiency used here is Pareto efficiency i.e. that it is impossible to make someone better off without making somebody else worse off. The answer to the question as to whether markets generate a Pareto efficient outcome is yes in the model of general competitive equilibrium; this is the first theorem of welfare economics. There are strong assumptions here, in particular the absence of imperfect competition and the existence of complete markets. This rules out externalities, see BVFD Chapter 14.5. It also requires that the economy works as if you could buy now everything you wanted in the future, taking into account the circumstances. For example there is a market which sells the use of an umbrella next Wednesday if it turns out to be raining, but not if it turns out not to be raining. The lack of this kind of markets is referred to briefly in BVFD Chapter 14.7. • Does equity, the distribution of wealth and income, matter? Economists usually consider this to be a normative question, a moral and political judgement. But there may be important ways in which a highly unequal society functions differently from a more equal society, even for the well off. • Is there a conflict between equity and efficiency? The answer is no in the model of general competitive equilibrium if there is a way of redistributing endowments. This is the second theorem of welfare economics. (See BVFD 14.2, particularly concept 14.2 for an explanation of what an endowment is). Again there are strong assumptions underlying this result. Other models describe a conflict between equity and efficiency, for example in assessing the deadweight loss due to a tax. In practice there are very few policy changes which are Pareto improvements. There are gainers and losers. Who gains and who loses has very important implications for politics. • Are there ways in which markets fail? The answer is yes. Market failure is an important topic in economics, see BVFD 14.4–14.8. Most importantly the idea of market failure has very important implications for policy on climate change. As BVFD says in the section on equity and efficiency in section 14.2 there are differences of opinion as to how important people think market failure is. There is a correlation between views on the importance of market failure and positions on the political spectrum, with relatively more left-wing people tending to think that governments should take action to correct market failure and more right-wing people disagreeing. This is broadly correct but overly simple – people may believe one type of market failure is important, but not be so concerned about others. • What is the nature of government? Many of the ideas discussed in this block were originally developed by people living in the US or Europe under some form of democracy – although economists from a much wider range of nations have contributed to their subsequent development. Government, or the lack of government, has had very different impacts in different countries at different times. This is a topic much studied by economic historians and development economists. This is a good time to think back to the questions from Chapter 1 of BVFD which asked: what, how and for whom to produce. We have seen how this question is answered by free markets, concentrating mostly on markets for a single product or factor. Many economists would agree that the free market can do quite a good job in allocating resources. But 118 Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government how can we define what it means to do ‘a good job’? Welfare economics uses the concepts of efficiency and equity to make normative judgements about the workings of the market. There are reasons why markets fail in certain circumstances and this can provide a justification for government intervention in the economy. This block defines and discusses the concept of externalities, where there is a clear role for government intervention in the market. The following block will discuss the tools governments use including taxation, redistributive spending and regulation. This block on welfare economics is the first step towards looking at the economy as a whole system. In contrast to the second part of the course on macroeconomics, this block still uses microeconomic techniques; however, it examines welfare at the economy-wide level rather than focusing on a particular market. As such, the concept of general equilibrium is also an important part of this block. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • define welfare economics • describe horizontal and vertical equity • discuss the concept of Pareto efficiency • recognise how the ‘invisible hand’ may achieve efficiency • define the concept of market failure • recognise why partial removal of distortions may be harmful • identify the problem of externalities and possible solutions • discuss how taxes can correct for externalities • discuss how monopoly power causes market failure • analyse distortions from pollution and congestion • analyse the economics of climate change • discuss why public goods cannot be provided by a market. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 14, except 14.7 and 14.8. Synopsis of this block This block examines how well markets work without intervention, as well as various justifications for government intervention in markets. The concepts of efficiency and equity are used to evaluate and make normative judgements about various outcomes. Definitions are provided for horizontal and vertical equity, as well as productive, allocative and Pareto efficiency. Perfectly competitive markets are both productive and allocative efficient. The concept of general equilibrium is introduced, which refers to a situation where multiple (or all) markets are simultaneously in equilibrium. Reasons for market failure include taxes, imperfect competition, externalities, missing markets and imperfect information. When only one market is distorted, the first-best solution is to remove the distortion. However, when this is not possible or there are reasons why governments prefer not to remove the distortion (for example for equity reasons), the theory of the second-best says it is better to spread the distortion thinly over many markets than concentrate it in one market. Governments can also act against externalities and other distortions by allocating property rights or imposing regulations. 119 EC1002 Introduction to economics Equity and efficiency ► BVFD: read the introduction to Chapter 14 and section 14.1. This section introduces the twin notions of equity and efficiency. It is particularly important to understand clearly the definitions of Pareto optimality (an allocation of resources is Pareto efficient if any reallocation would make at least one person worse off) and Pareto gain/improvement (a reallocation of resources that makes at least one person better off without making anyone worse off). Many would argue that governments should favour reallocations that result in Pareto improvements, although that is itself a value judgement (note the key word ‘should’). While the notions of Pareto efficiency and Pareto improvements are useful principles, they do have their shortcomings when applied to actual policy decisions, for at least two reasons. Firstly, there are generally many Pareto optimal allocations so further value judgements are required to choose the best allocation from the set of such efficient allocations. Secondly, many policy decisions have both winners and losers; adopting policies of this kind are not Pareto improvements because some people are made worse off. Equity can be broken down into horizontal and vertical equity. Horizontal equity is ‘the identical treatment of identical people’ while vertical equity has to do with treating people in different situations differently so as to reduce inequalities between them. Vertical equity is the more contentious of these two principles; it is hard to see why one would not want to treat identical people identically, while the optimal amount of vertical equality is a matter of considerable debate. Efficiency has to do with making the best use of scare resources to satisfy people’s needs and desires and can be broken down into productive and allocative efficiency. To discuss efficiency further, it is useful to come back to the production possibility frontier PPF introduced in Block 1 and illustrated below. Output of good A F B C A D E Output of good B Figure 10.1: The production possibility frontier. Productive efficiency is represented by any point on the PPF. Points beyond the frontier (such as F) are unattainable and points inside (such as A) are inefficient. Productive efficiency implies that goods and services are produced at their lowest cost (recall from Block 5 that this has to do with firms choosing their cost-minimising mix of inputs using the condition that their isocost curves and isoquants are tangent to each other). More output of one good can only be obtained by sacrificing output of other goods. Allocative efficiency has to do with the choice between different combinations of output – only one point on the PPF is allocatively efficient. This is the point that aligns the efficient production possibilities with the 120 Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government needs and preferences of society. A point on the PPF is allocatively efficient when it is not possible to move to a different point on the PPF and make someone better off without making someone else worse off. Allocative efficiency is achieved when P = MC, since this means that benefit and cost are equated. Allocative efficiency occurs when the marginal benefit equals the marginal cost of producing one extra unit. An equilibrium may be productively efficient without being allocatively efficient. In other words, a market where the output generated is being maximised isn’t necessarily maximising social welfare. As stated above, a Pareto efficient allocation is an allocation there is no other feasible allocation that makes someone better off without making anyone else worse off. It relates to both productive and allocative efficiency. Equity and efficiency are separate concepts. Efficiency doesn’t automatically imply equity. For example: An economy contains two people and two goods, oranges and bananas. Both people like both goods, but value them differently. For person 1, one orange is exactly equivalent to two bananas, while for person 2, two oranges are exactly equivalent to one banana. In this case, the three following allocations are all Pareto efficient: • Person 1 has all the oranges and person 2 has all the bananas. • Person 1 has all the oranges and all the bananas. • Person 2 has all the oranges and all the bananas.1 It is clear that while options 2 and 3 are both Pareto efficient, they are also highly inequitable! It is often, but not always, the case that there is a trade-off between equity and efficiency. An example of a government policy designed to increase equity that can have a negative effect on efficiency is progressive marginal taxation, since the high marginal tax rates on those with higher incomes can reduce work incentives, reducing GDP and/or growth. In addition, if everyone had the same income, there would be no incentive to work hard, to change jobs, or even to get an education. Given the widespread existence of progressive income taxation it would appear that people are happy to trade off some efficiency for the improvement in equity, which progressive income taxes deliver. Although equity and efficiency are often conflicting objectives, it is important to note that this need not always be the case. An improvement in efficiency should generally improve the workings of the economy and generate increased growth for all. Increased efficiency and greater equity are compatible with each other. Another possible example of a policy that may not imply a trade off is subsidising the education of children in low income households; this can lead both to a more equal distribution of earnings and a more productive workforce. There is no reason why improved efficiency must necessarily lead to inequality. ► BVFD: read section 14.2, as well as concepts 14.1 and 14.2. Why are these three combinations Pareto efficient? If person 1 has no bananas then any trade that makes him better off must involve him getting at least twice as many bananas as he gives up in oranges, which results in person 2 being worse off. Similarly, if person 2 has no oranges then any trade that makes her better off must involve her getting at least twice as many oranges as she gives up in bananas, which results in person 1 being worse off. On the other hand, if person 1 has some bananas and person 2 has some oranges, then by transferring one banana from person 1 to person 2 and one orange from person 2 to person 1, both of them are made better off. 1 Efficiency and market structure We have seen previously (in Block 6) that perfect competition is allocative efficient because it maximises the sum of producer and consumer surplus. A further reason is because under perfect competition, marginal cost will be equal to price in all industries. In order to maximise profits, firms will produce where MR = MC. Also, MR = P under perfect competition 121 EC1002 Introduction to economics because the firms face a flat demand curve and therefore have a flat MR curve which is the same as the demand curve. Thus, P = MC under perfect competition. Productive efficiency can occur under a variety of market structures, as firms will wish to produce at minimum cost in order to maximise profits. However, allocative efficiency only occurs under perfect competition. In imperfectly competitive markets, firms are allocatively inefficient as P > MC. Perfect competition has consumers trying to maximise their utility and producers trying to maximise their profits. Market forces ensure that an equilibrium is reached where gains to all parties are maximised. Competitive equilibrium ensures that there is no resource transfer between industries that would make all consumers better off. General equilibrium ► BVFD: read concept 14.1 – general equilibrium. Concept box 13.1 takes a general equilibrium perspective. Up to now, we have examined equilibrium in markets for a single good or a single factor of production, this is known as a partial equilibrium approach. General equilibrium refers to a situation where multiple (or all) markets are simultaneously in equilibrium. Concept box 14.2 shows a general equilibrium between two consumers in an exchange economy, but at the level of the market we can use our basic supply and demand analysis to analyse general equilibrium. We need to move from a partial to a general equilibrium approach when there is significant interdependence between markets; where markets are completely independent of each other, partial equilibrium analysis suffices. The following activity is designed to help you to understand how two markets interact and how equilibrium is attained when the goods are substitutes. The technique is applicable also in input markets and for complementary goods or factors. Activity SG10.1 Coffee and tea are substitutes. The demand for each depends on its own price as well as the price of its substitute. Supply and demand curves are given as follows: Coffee demand: Q DC = 60 – 6PC + 4PT Coffee supply: Q SC = 3PC Tea demand: Q DT = 20 – 2PT + PC Tea supply: Q ST = 2PT where PC is the price of coffee, PT the price of tea. a. Find the equilibrium prices and quantities for coffee and tea. Hint: both markets must be simultaneously in equilibrium. b. Suppose that there is a major failure in the coffee crop, leading to a large reduction in supply. Use supply and demand diagrams to trace out the effect in both markets. In the new equilibrium what happens to the equilibrium price and quantity of tea? The Edgeworth box ► BVFD: read concept 13.2 – the Edgeworth box2 122 Named after Francis Ysidro Edgeworth (1845–1926) a pioneer of neo-classical economics, especially utility theory (including indifference curves). He was the founding editor of The Economic Journal, the most prestigious British academic journal of economics. 2 Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government The Edgeworth box, here applied to exchange only (there is also a production version) is one of the more ingenious diagrams in economics. It looks complicated and difficult, and it does take a bit of time to master, but the basic ideas are actually quite straightforward. The key question behind the movements within an Edgeworth box is, if the two parties trade, can they achieve a better allocation compared to their initial endowment, and will this outcome be Pareto optimal? In fact, market forces (working through the price mechanism) will achieve a Pareto-optimal allocation when the two parties trade with each other. Furthermore, changes can be made to the initial endowment so that any particular Pareto-optimal outcome can be achieved. As such, the Edgeworth box can be used to demonstrate the two theorems of welfare economics defined above. Activity SG10.2 Household A and B of an exchange economy with two goods x and y have the utility functions UA(xA, yA) = xAyA UB(xB, yB) = xByB Household A has the initial endowment 10,16) and Household B has (25,12), so the total amount of good x in the economy is 35, while the total amount of good y is 28. a. Illustrate the initial endowment in an Edgeworth box b. Assuming that this point is not on the contract curve, draw possible indifference curves for the two households and indicate the area where trade could result in an improvement for both households (you can draw standard indifference curves without reference to the utility functions given above). y y c. These utility functions imply MRSA = xAA and MRSB = xBB . Also, suppose the price of good x is £0.80, while the price of good y is £1. Use this information to find the Pareto optimal point. Clearly state which household sells which quantity of which good and the final Pareto-optimal allocation. d. Calculate the utility of the two households at the initial endowment and at the new optimal point. e. Draw your solution onto your graph along with the budget constraint and the new utility curves at this point. Also draw the contract curve on your diagram. Distortion of the market ► BVFD: read section 14.3. This section reviews the effect of a specific tax on a good and emphasises that, at least in the absence of other distortions, this will lead to a distortion in the market for the taxed good – the marginal benefit to consumers is no longer equal to the marginal cost to producers. The fact that taxes are often distortionary is not an argument against all taxation, but highlights one important aspect of taxation that must be considered in designing a tax system. ‘Second best’ has to do with introducing new distortions to offset existing distortions and improve efficiency. Taxation is one specific distortion, and the concept of second-best implies widespread taxation may be more efficient than taxes in a single market, because this helps to keeps relative prices intact. Chapter 15 (covered in the next block) goes into more detail on taxation. Another way of stating the theory of second best is that when there are several distortions in place (taxes and subsidies on various goods for example) it is not always desirable to eliminate some of these distortions; if markets were otherwise competitive, 123 EC1002 Introduction to economics eliminating all distortions would be efficient, but eliminating some but not others could actually make the situation worse (increase inefficiency). The intuition is that some of the distortions may have been offsetting others and piecemeal removal of distortions may destroy this balance. Sources of market failure ► BVFD: read section 13.4. This section introduces the potential sources of market failure that can prevent a free market allocation of resources from being efficient, but doesn’t analyse them in depth; subsequent sections do that. The following is a list of sources of distortions that lead to market failure. Read through and make sure you understand what each of these means: • market power • asymmetric information • taxation • common property • public goods • missing markets • externalities Common property All of these are described in BVFD except common property, which refers to a resource such as fishing grounds or common grazing land, which is open to everyone, but where one person’s activities detract from the total available to everyone (in this sense common property can be thought of as a kind of externality). For example, fish in the ocean can be caught by anyone, but once one is caught, no-one else can catch it. Common property tends to be over used, leading to a degradation or depletion of the resource. This is because individuals only take into account their private costs and benefits and neglect the social cost of their actions. For this reason, various kinds of sea life are nearing extinction due to overfishing. This problem applies to any common resource which is unregulated. Externalities ► BVFD: read section 14.5 and case 14.1. This section explores in greater detail one of the sources of distortions listed above – externalities. Externalities can either be positive or negative and occur when there is a divergence between the private marginal costs and benefits and the social marginal costs and benefits of production and consumption. If a restaurant plays loud music, this could be either a positive or negative externality for the restaurant next door, depending on whether that restaurant’s clients like the music and are attracted to eat there because of it, or if it detracts from their dining experience and makes them less likely to choose that restaurant. In the case of a negative externality, the restaurant playing the loud music may be required to compensate its neighbour for their lost customers. In the case of a positive externality, they could even ask the neighbouring restaurant to contribute to the costs of playing the music, since that restaurant is also gaining a benefit from it. The issue with externalities is that these payments will not generally occur unless there is regulation, because there is no market for the externality. The amount of noise produced by the first restaurant will therefore be inefficient – either too much (ignoring the negative impact on its neighbour) or too little (ignoring the positive impact on its neighbour). 124 Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government Activity SG10.3 Using the equations below, find the level of production which will occur without regulation and the socially optimal level of production, and calculate the social cost of the externality. Graph your answers and shade in the area representing the social loss of inefficient production. Example 1: Grating, unpleasant music Demand: DD = £40 – 0.3*Q Marginal private cost: MPC = £10 Marginal social cost: MSC = £10 + 0.1*Q. Example 2: Beautiful, pleasant music Marginal private benefit: MPB = £20 – 0.2*Q Marginal social benefit: MSB = £24 – 0.2*Q Marginal cost: MPC = MSC = £4 + 0.2*Q. As the next section BVFD Chapter 14.6 discusses, we live in an age where the theory of externalities is ever more important; climate change, the effects of pollution on human health and biological diversity, and many other examples are increasingly at the centre of policy debates. This section of BVFD covers the assignment of property rights as a method of dealing with externalities. It is important to realise that, just as the optimal size of the neighbour’s tree is not zero in the example illustrated in Figure 14.7, the fact that industrial production generates pollution as a side effect does not mean that the socially optimal level of pollution is zero; what is required is that the marginal cost of pollution is equal to the marginal benefit (if it seems strange to you that pollution can have benefits, consider the effect on the costs of production of requiring firms to reduce pollution levels). ► BVFD: read Maths A 14.1. This maths box provides a mathematical explanation of Coase theorem, which states that an efficient use of resources can be achieved through the allocation of property rights, and that this is not affected by whether the party causing the externality or the party suffering from it is given the property rights. In the story in this Maths box, the right to pollute is given to Firm A. Since Firm A can sell this right to Firm B, the cost and revenue functions of Firm B become relevant to Firm A’s production decisions. For this reason, Firm A will decide on a level of polluting where the marginal private cost is equal to the marginal social cost – the efficient level of pollution in this scenario. As the textbook suggests, try to work out the case where B is given ownership of the right to pollute. Please work through the maths box to absorb the basic ideas behind the Coase theorem (and also understand the reasons why it may be difficult to apply in practice). ► BVFD: read section 14.6 and activity 14.1. The analysis of greenhouse gas emissions is an application of the principles discussed in section 14.5 – namely a situation where marginal social costs dramatically exceed marginal private costs. Having determined the optimal level of emissions in the aggregate, the key economic principle in terms of achieving this target efficiently is the equalisation of the marginal cost of emissions reduction between businesses/factories. That is the aim 125 EC1002 Introduction to economics of the market-based programmes such as cap-and-trade, as they use the trading of credits between firms to allow firms with a lower marginal cost of reducing emissions to reduce more and firms with a higher marginal cost of reducing emissions to reduce less. This section also introduces the important topic of social discounting and its central role formulating climate change policy. Discount rates have to do with adjusting future or past values so that values from different time periods can be properly compared. The choice of the appropriate social discount rate is complex, and probably involves some value judgements. Complex as these issues are (and they would be studied in more depth in a specialist course on public economics, environmental economics or cost-benefit analysis), they are vital in determining today’s policies. Taxes and externalities ► BVFD: read section 15.4, case 15.3 and Maths 15.2. We have seen how an externality distorts the market, giving rise to inefficiency. While the assignment of property rights can correct the externality, this may not be possible. Externalities are thus an area that may provide a strong justification for intervention through regulation. These sections show that a tax, known as a Pigouvian tax, can be used to correct for an externality. This is shown formally in Maths 15.2. The firm with a negative production externality will take this into account when determining the level of production, such that their quantity of production will be the socially optimal quantity. It is also possible to introduce Pigouvian subsidies to increase activities with positive externalities. While this maths box uses calculus, the basic analysis is the same as that illustrated in Figure 15.6. The tax has to be set at a level equal to the marginal damage caused by the externality at the socially optimal level of output – it has to raise private costs so that private decision making generates the socially optimal quantity. While this seems like an easy fix, determining the optimal size of the Pigouvian tax is non-trivial, as that would require estimation of the marginal damage caused by the externality. Public goods ► BVFD: read section 15.2 and case 15.2. Markets tend to deal best with private goods, but there are several other types of goods which exist. These categories depend on the combinations of two distinct characteristics: rivalry and excludability, as defined in BVFD. The table below clarifies all four theoretical types of goods with examples. Rival Excludable Non-excludable Private goods Examples: ice cream, mobile phones Common property Examples: fisheries, common grazing land Non-rival (up to Club goods Examples: capacity) cinemas, toll roads 126 Public goods Examples: defence, police force Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government Activity SG10.4 Complete the following table: Good Excludable/ non-excludable? Rival/ non-rival? Type of good Air Bacon Coal House Private park Publicly broadcast radio Satellite Timber For public goods, non-excludability results in the free-rider problem. Because people cannot be excluded from consuming the good once it has been produced even if they don’t pay for it, they have no incentive to pay voluntarily and the good is unlikely to be produced at all.1 That is why there is a clear role for government in the production of public goods, especially important goods such as national defence and policing. It should be noted, however, that the characteristics that make it difficult to get the good produced privately may also cause problems for public provision. It is important to understand, see Figure 15.2 and the accompanying text, that in analysing the optimal (efficient) amount of the public good to produce, the demand curves of individual consumers are summed vertically in order to get the overall demand or the marginal social benefit at each quantity. Compare this with the method of getting the market demand curve from the demand curves of individual consumers for a private good. There, we summed the individual demand curves horizontally. Each consumer of a private good equates marginal benefit to price and price is equal to MC in a competitive market. The differences between private and public good equilibria can be characterised, for the case of N consumers, as follows: Private good (perfect competition): q1 + q2 + ... + qN = Q MB1 = MB2 = ... = MBN = P = MC Public good: q1 = q2 = ... = qN = Q MB1 + MB2 + ... + MBN = MSB = MC where qi are individual quantities and Q is total quantity. The MBs are private marginal benefits, MSB is social marginal benefit and MC is marginal cost. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. 127 EC1002 Introduction to economics Overview This block provides an introduction to welfare economics, which involves normative judgements as to how well the economy is working. Two key concepts are equity (horizontal and vertical equity) and efficiency (productive and allocative efficiency, as well as Pareto efficiency). The textbook shows that perfect competition, under strict assumptions, is Pareto efficient, since under perfect competition MC = MB = P. Much of economic policy making concerns a conflict between equity and efficiency. For example, redistributive taxes improve vertical equity but are not allocative efficient. Perfectly competitive markets are rare in practice and, in reality, there are many distortions which lead to market failure. Distortions occur whenever free market equilibrium does not equate marginal social cost and marginal social benefit. Key sources of distortions are taxes, imperfect competition, externalities, and missing markets. The first best solution to a distortion is to remove it and restore efficiency, however, if distortions cannot be removed or if policy makers would rather leave them in place than lose the benefits to equity that arise through these distortions, the second-best solution is to spread distortions widely over many markets rather than concentrating the distortion in a single market, looking for ways in which distortions can be offsetting rather reinforcing. A major cause of market failure is externalities – there are both production or consumption externalities and these can be either positive or negative. An externality occurs when there is a divergence of private and social costs and benefits due to the absence of a market for the externality itself. Inefficiencies can also occur due to information problems, such as moral hazard, adverse selection and incomplete information. Regulations provide information and express society’s value judgements about intangibles. Externalities provide a further justification for government intervention. These can be dealt with through the allocation of property rights, the levying of taxes and/or subsidies which cause the private sector to internalise the externality, or the imposition of standards/regulation. Public goods are non-rival and non-excludable, and as such will tend to be underprovided in private markets due to the free-rider problem. Governments can provide public goods, though the socially optimal level can be difficult to determine in practice. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. Suppose that Bill, Jill and Al constitute the entire market for consumers of national defence. Each individual has an identical demand curve for national defence, which can be expressed as P = 50 – Q. Suppose that the marginal cost for national defence can be expressed as MC = £30. What is the optimal quantity of national defence? a. 150 units b. 60 units 128 Block 10: Welfare economics and the role of government c. 40 units d. 20 units. Draw a diagram showing the analysis. 2. Which of the following statements is correct? a. If a good is public then consumption by one person does not reduce the amount available for other people. b. A public good is a good that the government pays for. c. Congested roads carrying a large amount of traffic are public goods. d. A public good is a good produced by the government True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Each person should be willing to spend more on a public good than a private good, as the benefits it creates can be enjoyed by everyone. 2. There is no need to impose a carbon tax if property rights are assigned. 3. If there is a negative production externality, then the optimal output is zero. Long response question 1. Planting a tree improves the environment: trees improve soil quality and water retention in the soil, transforming greenhouse gases into oxygen. Assume that the value of this environmental improvement to society is £1 per tree for the expected lifetime of the tree. The following equation provides the marginal private benefit: MPB = 40 – 54 Q where Q refers to the quantity of trees demanded in thousands. a. Assume that the marginal cost of producing a tree for planting is constant at £20. Draw a diagram that shows the market equilibrium quantity and price for trees to be planted. b. What type of externality is generated by planting a tree? Find the optimal number of trees planted and illustrate. How does this differ from the market outcome? c. What is the deadweight loss corresponding to the market outcome? d. What policies would you suggest to reach the optimal outcome? 2. An artist produces metal sculptures using a noisy production process. Let’s say the demand curve (showing the marginal social benefit) can be expressed by the function: MSB: P = 80 – 2Q where Q is the number of sculptures The artist’s marginal private cost of producing sculptures is given by: MPC: P = 2Q while the marginal social cost is higher, since other people also experience negative effects due to the noisy production process: MSC: P = 6Q. 129 EC1002 Introduction to economics Given these equations, find a. the free market equilibrium (price and quantity) b. the socially optimal price and quantity c. the Pigouvian tax that should be charged on the artist so that the social optimal quantity of sculptures is produced d. the revenue this tax will raise. Food for thought – Box 3: Why is climate change such a challenge? Climate change is one of the most pressing global challenges, with potentially disastrous consequences, as highlighted by the 2022 UN-IPCC report . It finds that many of the humaninduced changes (the continued sea level rise, rising global temperatures and frequency of extreme weather) are unprecedented, and already ‘irreversible’ for centuries or millennia ahead. Scientists generally attribute the increase in global temperature to human-induced expansion of the ‘greenhouse effect’, where the atmosphere traps heat radiating from Earth toward space. This is closely linked to increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Thus, a key channel for containing climate change is to reduce GHG emissions to sustainable levels. But why aren’t we doing a better job at doing so? The answer – or at least part of the answer – relates to fundamental concepts of externalities and coordination failure. First, the decision to either directly or indirectly contribute to GHG emissions is often an example of externality: where a person’s decision affects unrelated third parties. For instance, a farmer may not consider the full cost of burning forests to clear land for farming, leading to too much forest burning than is desirable and, in turn, more GHG emissions than is socially optimal. Second, at an international level, the aim of reducing GHG emissions is complicated by the presence of coordination failure between countries. Countries have often, and continue to, pledge their emissions reduction goals (for instance, the Kyoto Protocol in 1992 and, more recently, the Paris Agreement in 2016), however, these pledges remain non-binding and countries are tempted to ‘miss their aims’, despite evidence showing that international coordination is critical to reverse global warming and tackle climate change. When each country considers if they will act on their pledge to cut GHG emissions, they face a dilemma: whereas the cost of policies to curtail emissions are clear (higher energy costs, loss of competitiveness in the short run), the benefits of enforcement (less global warming, less extreme climate) are highly dependent on other countries’ actions. If other countries choose not to enforce their pledges, then the efforts of individual countries may be of limited effectiveness in reversing the global trend. Meanwhile, there is no ‘international government’ to enforce international pledges so, despite coordination being beneficial to all, there is likely to be a coordination failure, with each country experiencing an incentive to deviate from their pledge. To read more about the challenges of international climate coordination, you can access a recent article by joint 2019 Economics Nobel prize winners Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo: Banerjee, A. and E. Duflo ‘If we can vaccinate the world, we can beat the climate crisis’ , The Guardian June 2021. 130 Block 11: Introduction to macroeconomics Block 11: Introduction to macroeconomics Introduction Macroeconomics is the study of the economy as a system. While microeconomics is focused on the choices of an individual household or firm and interactions in a particular market, macroeconomics examines the whole economy and is therefore concerned with aggregates. The demands of all the individual consumers and the supply provided by all individual firms are aggregated together into a whole. It examines incomes, production and prices in the aggregate rather than for particular individuals, firms, markets or industries. The role of the government and the financial markets in the economy also become much clearer, as do the effects of international trade and financial transactions. Macroeconomics makes it possible to examine certain questions which relate to the whole economy, and which are difficult to answer if we just focus on any individual market. Issues such as unemployment, inflation and the business cycle can be studied much more effectively using the tools of macroeconomic analysis and these and other issues will be covered in the second part of the guide. We do this through the study of macroeconomic frameworks that help us explain key trends and fluctuations in total economic activity. This block provides an introduction to macroeconomics. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • describe the nature of macroeconomics as the study of the whole economy • discuss internally consistent national accounts; why measuring GDP by income, by expenditure or by output produces the same result • explain the circular flow between households and firms • recognise and understand the identity Y ≡ C + I + G + NX • explain why leakages always equal injections • identify nominal versus real measures of national income and output • describe the shortcomings of GDP as a measure of economic activity and wellbeing • analyse more comprehensive measures of national income and output. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 17. Synopsis of this block This block (based on Chapter 17 of the textbook) provides an introduction to macroeconomic analysis. The major concepts you will need to gain a detailed understanding of are GDP – what it means and how it is measured; national income accounting, especially the concept of value added; and the circular flow of income, including injections and leakages into and out of the system. These will be introduced in the textbook chapter and the exercises and revision questions in this block are designed to help you work 131 EC1002 Introduction to economics through the key points and gain a better understanding. This will provide a foundation for more in-depth analysis in the following blocks. Macroeconomic analysis ► BVFD: read the introduction to Chapter 17 and sections 17.1. The introduction to Chapter 17 offers a helpful yet brief explanation of the difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics in terms of how economic analysis is simplified so that it is manageable – microeconomics focuses on particular markets, while macroeconomics stresses broad aggregates. The six definitions within section 17.1 are important, basic concepts that you need to know – make sure you are familiar with them before continuing. The key questions we wish to answer from the study of macroeconomics are: • Why do economies typically grow and why do some grow perform better than others? • Why do economies go through “booms” and “busts” or even financial crises? • Why is there always unemployment? Why does it vary across time and countries? • Can governments stabilise the economy? How should they set economic policies such as taxes, public spending, and interest rates? • Interdependency of different parts of the economy is more important in macro. • One person’s spending is another person’s income; one person’s borrowing is another person’s saving. ► BVFD: read section 17.2. Activity SG11.1 Do you know the long-term trend of growth, unemployment and inflation for your own country? If you live outside the UK/USA/EU/China it would be useful to attempt to replicate Table 15.1 for your own country. This will help to provide you with some empirical context for your study of macroeconomics and also show you how your own country relates to the places that the textbook has selected. You can use the following websites to do some research: • stats.oecd.org • data.worldbank.org • www.imf.org/external/datamapper • www.worldeconomics.com The circular flow of income ► BVFD: read sections 17.3,17.4 and case 17.1 The economy can be described using a simple two-sector model containing just households and firms, as represented in Table 17.4 and Figure 17.2. Households earn income in exchange for offering their factor services, then save or spend this income on goods and services, produced by firms 132 Block 11: Introduction to macroeconomics who hire labour, capital and benefit from investment. It is a very simple framework with an injection into the system (investment) and a leakage (savings) out of the circular flow. Later, other sectors will be built into this model to make it more realistic. You may find the following comments on Table 17.4 helpful: • It is assumed that firms pay out to households the difference between the revenue they receive and the amount they pay to other firms for inputs which are used up in production. This is the value added by firms. It is helpful to think of this payment as having three parts: • Payment for things sold to firms by households. Think of this as the wages paid to labour. • Interest paid to households in return for money they saved and lent to firms to finance investment in the past. • Supernormal profits paid to households who own the firms. • You may know that in reality firms do not pay out all their profits to households, they retain some profits and use them to fund investment. You do not need to know about this for EC1002. • If you are still having difficulty understanding what is happening in table 17.4 you might find it helpful to change the word ‘car maker’ to ‘start-up’ in row 3, column 4. Assume that the car marker already has machines and does not need any new machines to produce cars this year. The story is now: • • The steel maker sells steel to the car maker and machine maker for £4,000. It pays zero to other firms. Value added £4,000 = amount paid to households. • The car maker buys steel from the steel maker for £3000 and sells cars to households for £5,000. Value added £5,000 – £3,000 = £2,000 = amount paid to households. • Machine maker buys steel from the steel maker for £1,000. Sells machines to the start-up for £2,000. Value added £2,000 – £1,000 = £1,000 = amount paid to households. • Start up invests in machines, it buys machines for £2,000. It not does not sell anything. It has to borrow £2,000 from households to buy the machines. This £2,000 is equal to both household savings and investment by the firm b. Value added zero = amount paid to households. Now think about the situation in which the car maker and the start-up merge, but all the transactions are the same. This gets back to table 17.4 in the book. It is now important to make a distinction between final and intermediate goods. Steel is an intermediate good, it is all used up in production and none of it goes to households. Cars are a final good, they go to households. Machines are a final good, they are there are the end of the year. Value added for the merged car marker and start-up is (revenue – amount paid to producers of intermediate goods), and is, as before, £2,000. By assumption the value added is all paid out to households, so the merged firm has to borrow £2,000 from households in order to pay for investment in machines. 133 EC1002 Introduction to economics Measuring GDP This section also describes the three equivalent ways of measuring the total economic activity in the economy, namely the: • value of all goods and services produced • total value of earnings arising from the factor services supplied • total value of spending on final goods and services. In principle, all methods should give the same answer; in practice, however, there are small statistical discrepancies. Also, ‘Food for thought box 4’ tackles the broader challenge of how we should measure the well-being of nations. When measuring GDP we need to think about intermediate goods. These are goods that are used in the production of other goods or services. What if firms need to buy goods/services from other firms to produce? We must avoid double counting. For example, e-commerce firms use telecommunications services as an input. An important concept that accounts for the fact that some ouput also serves as an input is that of value added: Value added = Value of production – Value of intermediate goods used. Activity SG11.2 Which of these three do you think is easiest to measure? What kind of data would you use if you were to try to measure economic activity in these three ways? Activity SG11.3 Fill in the blanks in the table below (based on Table 17.4) (1) Good (2) Seller (3) Buyer (4) Transaction (5) Value Value Added Wood Timber producer Stamp manufacturer £100 Wood Timber producer Paper Manufacturer £800 Stamps Stamp manufacturer Paper manufacturer £300 Special paper with stamped design Paper manufacturer Households £1,200 (6) Spending on Final Goods Total Transactions GDP ► BVFD: read Maths 17.1. It is important that you understand national income identities by the end of your study of macroeconomics for EC1002. You will likely benefit from the following discussion when you come to the revision stage of your studies, since the argument underlying it will be built up stage by stage through the course, as we introduce government and international trade. 134 (7) Household Earnings Block 11: Introduction to macroeconomics The first very important identity is: GDP ≡ Y ≡ C + I + G + X – Z where C denotes consumption I denotes investment G denotes government expenditure X denotes exports Z denotes imports. This equation represents GDP calculated by the expenditure method. You can also think of this as what the economy produces. The identity is also sometimes written as: Y ≡ C + I + G + NX where NX = X − Z corresponds to net exports. The other very important national income identity is Y≡C+S+T−B Where S denotes saving, T taxes, B denotes benefits (such as state pensions). This reflects what households do with their income. Let’s think a little further about where this comes from. Households have disposable income Y – T + B, which they can either save or spend on consumption. It can also be rewritten as: Y ≡ C + S + NT Where NT = T – B denotes net taxes. Taken together the two identities imply: C + I + G + NX ≡ C + S + NT Which can be rearranged to give: (S – I) + (NT – G) ≡ NX To explain the significance of this equation slightly differently from the text, suppose that the economy is running an external deficit (NX is negative, imports are greater than exports). This must have its counterpart either as a private sector deficit or as a public sector deficit (or both). If, in any sector, spending exceeds receipts there must be borrowing to pay for the excess spending. Suppose S = I in the private sector then, if the government is running a deficit (G > T), the government is borrowing from abroad and there is a deficit with the rest of the world (imports greater than exports). On the other hand, if the government account is in balance (spending = tax receipts) then a trade deficit (exports insufficient to pay for imports) requires borrowing in the private sector (I > S). Furthermore, we can simplify to the simpler framework of Figure 17.2; if the economy is closed or has balanced trade (NX = 0), and no government or a balanced budget (NT – G = 0), then it follows that savings must equal investment. It is important to recognise this is an identity – that is, it must always be true. In later blocks we move away from pure definition and examine in some detail economic theories about how each of the components of national income are determined. To understand why this identity must always hold, suppose that not all of the output the economy produced was actually sold in the period under consideration. Does this mean output is larger than 135 EC1002 Introduction to economics expenditure? No, the unsold output is inventory accumulation by firms (it is as if firms sold these goods to themselves) and this is included as part of investment. If in subsequent years firms run down their inventories, net investment falls. Note you will sometimes see this written as (S – I) + (T – G) ≡ NX where T is direct taxes minus welfare transfers. The general significance of the equation is the same as the one above. Before moving on to consider some welfare aspects of GDP, this might be a good time to remind yourselves of the relation between the major national income concepts summarised in Figure 17.3. Thus: • National Income at basic prices + indirect taxes = Net National Product • (Income) at market prices + depreciation = Gross Domestic Product at market prices + net property income from abroad = Gross National Product (Income) at market prices Activity SG11.4 1. Answer the following questions to check your understanding: a. Which components of GDP would each of the following transactions affect: b. Your family buys a new TV. c. All motorways are repaved. d. You buy a bottle of Italian wine. e. Porsche opens a new factory in England. 2. Why, in the absence of government and foreign sectors, are saving and investment always equal? How does this change when the government and foreign sectors are introduced? 3. The level of wealth can be measured by looking either at the gross national product or at the GDP. Suppose that the government wants to maximise total income of British citizens: which of the two concepts should it look at? Would you change your answer if the aim is that of maximising the total amount of economic activity occurring in the UK? 4. Leakages and injections – complete the following table. Item Leakage or Injection? Savings Amount (£m) 30 80 Taxes 40 Government Spending 20 Imports 25 Exports What is the formula that summarises this relationship? Gross domestic product (GDP) ► BVFD: read section 17.5 and case 17.2 and try to complete activity 11.1. This section deals with real versus nominal GDP, the GDP deflator, per capital GDP and the scope of GDP. 136 Block 11: Introduction to macroeconomics Activity SG11.5 Complete the exercises below to check your understanding. 1. Say the price level rises 10% from an index of 1 to an index of 1.1 and nominal GDP rises from £4 trillion to £4.6 trillion. What is nominal GDP in the second period? What is real GDP in the second period? 2. The table below shows nominal GDP for two countries A and B. Which economy experienced higher growth in real GDP per capita between 1960 and 2010? Country A Country B 1980 2020 Nominal GDP (current £bn) 20 2000 GDP deflator (2010=100) 8 100 Population (bn) 1 5 Nominal GDP (current £bn) 60 5000 GDP deflator (2010=100) 1 100 Population (bn) 3 5 ► BVFD: read section 17.6. Activity SG11.6 From the chapter as a whole, what are the advantages and limitations of GDP as a measure of wellbeing in an economy? ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. Overview This block started by describing the scope of macroeconomics and macroeconomics as a study of the economy as a whole. The circular flow was also introduced, and the block extended the discussion in the textbook to introduce the five-sector model, including households, firms, the government, the financial sector and the overseas sector. Leakages from the circular flow are always equal to injections, by definition. The net output of all factors of production is called GDP and this can be measured in three different but equivalent ways: income, production and expenditure. For the production method, including only the value added at each stage is important to avoid double counting. GDP can be measured at market prices or at basic prices (exclusive of indirect taxation). Furthermore, there is an important distinction between nominal GDP (measured at current prices) and real GDP (measured at constant prices). GDP, and in particular per capita GDP, is a useful indicator of a country’s economic situation, however, it does have limitations in terms of accuracy and comprehensiveness. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. 137 EC1002 Introduction to economics Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. Assume that a firm buys all the parts that it puts into a car for $10,000, pays its workers $10,000 to fabricate the car, and sells it for $22,000. In this case, the value added by the firm is: a. $2,000 b. $12,000 c. $20,000 d. $22,000. 2. Assume GDP is 6,000, personal disposable income is 5,100, the government budget deficit is 200, consumption is 3,800 and the trade deficit is 100. a. Saving (S) = 1,300, Investment (I) = 1,300, Government spending (G) = 1000. b. Saving (S) = 100, Investment (I) = 100, Government spending (G) = 200. c. Saving (S) = 200, Investment (I) = 100, Government spending (G) = 200. d. Saving (S) = 1300, Investment (I) = 1,200, Government spending (G) = 1,100. 3. The leakages and injections approach implies that the government surplus is equal to: a. private saving less private investment plus net exports b. private investment less private saving plus net exports c. private investment plus private saving plus net exports d. none of the above. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Katherine, who lives in Germany, recently bought a Lamborghini produced in Italy. Hence, Katherine’s purchase does not enter Germany’s GDP calculation. 2. In the absence of government and foreign sectors, saving and investment are equal. 3. The table below shows nominal GDP for two countries A and B. From the data in this table we can conclude that country A experienced higher growth in real GDP per capita between 1960 and 2010 than country B. Country A Country B 138 1960 2010 Nominal GDP (current £bn) 20 2000 GDP deflator (2010=100) 8 100 Population (bn) 1 5 Nominal GDP (current £bn) 60 5000 GDP deflator (2010=100) 1 100 Population (bn) 3 5 Block 11: Introduction to macroeconomics Long response question 1. The graph below shows the per capita annual GDP growth rate for Pakistan and the USA between 2000 and 2014. 6% 4% Pakistan 2% USA 0% –2% –4% 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from the World Bank. Source: www.google.com/publicdata/ explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_ a. What are the key features of the trend path for each country? b. Why is it important to compare per capita growth rates when countries have different rates of population growth? How might this apply to the case of Pakistan and the USA? c. Although Pakistan shows a faster growth rate for many of the years in the graph above, the level of per capita GDP is much lower, as can be seen below. Briefly discuss how the magnitude of each component of GDP is likely to differ for countries at different stages of development. 139 EC1002 Introduction to economics Food for thought – Box 4: How should we measure the wellbeing of nations? GDP, the value of goods and services in an economy, remains a central measurement, critical in informing macroeconomic analysis and policy, but — though hailed as a giant conquest of 20thcentury economics — has come under increasing fire in the 21st. In response, new indicators have been developed to supplement GDP, and the measurement of GDP itself has undergone many improvements by national statistical and inter-governmental agencies. The strongest and most longest-standing critique of GDP is that it is an inadequate measure of the welfare of the population, a task for which it was, indeed, not designed. The substantial growth of inequalities within countries (in contrast to the decline between countries) has highlighted the reality that GDP growth per capita may be very unequally shared. Median per capita household income is an obvious and important additional focal measure to highlight. In a more fundamental contribution, the United Nations Development Programme in 1990 launched the Human Development Index (HDI) as a weighted composite of variables representing national income per capita, but also health (life expectancy) and education (initially years of schooling and literacy rates). The HDI has itself been the focus of criticism, improvement and change, with particular attention to inequality. In a different direction, increased awareness that reported happiness has a tenuous link with income has led to the increased prominence of wellbeing measures, reflected in the annual World Happiness Report and the OECD’s ongoing ‘How’s Life?’ project. The latter was conceived in response to the 2010 ‘Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Report’ commissioned by the French government, which examined the limitations of GDP in a comprehensive critique spanning 291 pages. The 2015 British ‘Bean Report’ by LSE Professor Sir Charles Bean devotes a more modest 100 of its pages to desirable improvements in GDP, addressing both old and new challenges, some of which are enumerated here. The fact that a huge oil spill might increase GDP by stimulating economic activity in the clean-up is an example often cited in criticism of GDP. In response to increasing awareness of environmental damage, many ‘natural capital accounting’ measures have been developed, which continue to gain prominence in national reporting as countries progress towards Sustainable Development Goals. GDP from its inception excluded the value of services produced within the home, believing it would be impossible to measure and impute these with any accuracy. This led initially to critiques by those who believe it undervalues the contributions of women. Now this ‘production boundary’ presents an even larger challenge in the digital age, in which we produce our own entertainment online, act as our own travel agents and conduct valued searches for information without any cost except the inconvenience of ads. The world of extremely low marginal cost created by increasing digitalisation has accelerated the need to address problems posed by the fact that (more difficult to measure) services have been steadily expanding as a weight in national output at the expense of goods. Each criticism and new challenge has, in turn, given rise to improvements in and additions to the measurement of GDP and well-being, but none has yet produced a replacement for GDP itself as a ‘clear and appealing’ overview of a national economy, in the words of EU critics of the original. Read more about the OECD How’s Life? Project on their website. 140 Block 12: Supply-side economics and economic growth Block 12: Supply-side economics and economic growth Introduction We begin the study of macroeconomics by focusing on the determinants of productive potential in the long run, since GDP is the sum of goods produced. Starting with supply-side economics, the block moves on to discuss historical trends of long-term growth in various countries as well as models which have been proposed to explain these trends. Sustained economic growth has led to vast improvements in living standards, as measured by growth in per capita output. We wish to explore the sources of this growth and examine whether we can expect it to continue indefinitely. Moreover, what policies are good (or bad) for growth? At the same time, there is a lot variation in growth across countries, with a large gap between rich and poor countries. We therefore are also interested to examine whether we can expect the poor to catch up with the rich. The two key models presented in this block are the Solow model – including population growth, depreciation and technical progress; and the Romer model of endogenous growth. We build the Solow model up formally, beyond the coverage in the textbook, whereas for the Romer model we focus on the main ideas rather than the formal mathematics. Work through the material carefully – the equations, the graphical representations, and the explanations – so you gain a robust understanding of these models and their insights. You are also encouraged to do some research for your own country to find out what the long-term rate of growth has been, specific factors driving or hindering growth in different periods, and how this fits into the world economy, as well as with the models seeking to explain long-run growth. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • explain supply-side economics • discuss growth in potential output • describe Malthus’ forecast of eventual starvation and how technical progress and capital accumulation made this forecast wrong • describe the Solow model of economic growth • explain the convergence hypothesis • analyse the growth performance of rich and poor countries • discuss endogenous growth and the potential impact of policy on growth • discuss the implications of growth for environmental sustainability. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 18. 141 EC1002 Introduction to economics Synopsis of this block This block discusses supply-side economics and long-run economic growth. Data on growth rates from a variety of countries over different periods are presented. Although many factors contribute to countries growth rates, the basic inputs are land, raw materials, labour, human capital and physical capital. The way these inputs are combined through technology also has a huge impact, and technological progress is identified as the key factor facilitating permanent growth in output per worker. This block introduces models seeking to explain economic growth, notably the Solow growth model and the Romer model of endogenous growth. Furthermore, limitations in the measurement of economic growth and the costs of growth itself are also discussed. Supply-side economics ► BVFD: read the introduction to Chapter 18 and section 18.1. While the main focus of this block is on economic growth (i.e. sustained increases in economic well-being, the chapter begins with a discussion of factors that can lead to one-off changes in output. Analytically, these can be characterised as increases in any of the inputs in the economy’s aggregate production function (see BVFD section 18.3) or anything that makes a given level of these inputs more productive. Economic growth can be represented very simply as an outward shift in a country’s PPF. The frontier is determined by the quantity and productivity of a country’s resources (land, labour, capital and raw materials), and an increase in either will lead to an expansion in the country’s production possibilities. Output of good A The textbook discussion on increasing labour input implicitly holds population constant, but of course increases in population can increase labour input and total output as well. The effect of population growth on per capita output is, of course, another matter, as we discuss below. 1 Output of good B Figure 12.1: PPF before and after economic growth. Section 18.1 discusses supply-side policies with regards to labour input1 and labour productivity. More broadly, supply-side policy includes any policy that improves an economy’s productive potential, with the aim of shifting long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) to the right (we will discuss 142 Block 12: Supply-side economics and economic growth the LRAS curve a lot further in Block 17). Supply side policies include low marginal tax rates, competition policy, privatisation of state industries, and reducing unnecessary red tape and bureaucracy. Generally, supply-side policies aim to increase flexibility in product or labour markets, remove distortions to incentives, improve the quantity and quality of labour, and increase an economy’s competitiveness. Below is an extract from a speech on the role of supply side policies by Jean-Claude Trichet, the President of the European Central Bank, in 2004: The supply side of an economy is responsible for mobilising resources to supply goods and services, entailing as a crucial part the supply of labour and capital. The supply side thus contributes to determining the economy’s potential growth path and the real income of its citizens. Any malfunctioning of the economy’s supply side is thus tantamount to leaving opportunities for raising the welfare of its citizens non-exploited. In this regard, the best economic measure for raising income opportunities is the implementation of policies, which help the supply side operate flexibly and efficiently. These policies include, among many others, education, research and development. For the euro area, the focus is increasingly shifting to how lasting impediments to the functioning of these policies can be removed with the help of structural reforms. Such well-designed structural reforms increase the mobility of production factors towards their most efficient use, thus raising factor productivity, opening up additional employment opportunities and allowing for lower prices of goods and services. By exploiting the opportunities of such a more efficient allocation of production factors, welldesigned structural reforms allow the economy to reach a higher sustainable long-run growth path, higher employment, higher real incomes and thus a higher level of welfare. As noted in BVFD, however, effective supply-side policies are difficult to implement and often have dramatic consequences for equality and redistribution. Various policies have been more or less successful in different contexts, BVFD arguing that such policies are most likely to succeed in countries where free markets can operate with minimum regulation at the one extreme or centrally planned economies at the other. Activity SG12.1 Do some research to find out if the current government in your country is pursuing active supply-side policies and provide some examples of these. Economic growth ► BVFD: read section 18.2. This section explores the historic trends in economic growth, noting that there was very little economic growth in what are now industrial economies until the 18th century. Thereafter we see growth taking off in many countries, albeit with some countries growing at a faster rate than others. An interesting observation reinforced in Figure 18.2 and in Table 12.1 is that anything that affects the long-run rate of economic growth by even a very small amount makes a vast difference to potential output after a few decades. For example, a difference in annual growth rates of just half a per cent leads to huge differences in living standards after 25 or 50 years. 143 EC1002 Introduction to economics Annual growth rate of income per capita Increase in standard of living 10 years 25 years 50 years 100 years 3.00% 34% 109% 338% 1,822% 3.50% 41% 136% 458% 3,019% Source: own calculations based on Mankiw (Macroeconomics, 8th edition, 2012) Table 12.1. Annual growth and standard of living differentials over time. Inputs to production ► BVFD: read sections 18.3 and 18.4 as well as case 18.1. These two sections describe the inputs to production and provide information that will be very useful in understanding the models of economic growth introduced later in the chapter. Section 18.3 can be summarised in a production function as follows: Y = f(Capital,Labour,Human Capital,Land,Raw Materials) The amount of output that the available factors of production can produce depends not only on the amount of each factor, but also on scale economies and the way that the factors of production are combined, for example, higher human capital may lead to higher output directly as well as through increasing the productivity of capital. Adding technical knowledge to this, as per section 18.4, can be expressed in the following production function, where A represents technical progress. Y = A * f(Capital,Labour,Human Capital,Land,Raw Materials) This section emphasises the importance of investment to drive invention and innovation. Much technical progress is the result of activities by profitseeking firms. To encourage this, governments provide protection for their ideas in the form of patents. Furthermore, governments also subsidise research and development, for example in universities. Writing in the late 18th century, Robert Malthus was concerned that the fixed supply of land in the face of a growing population would, due to diminishing returns to labour, result in eventual starvation as output would grow less quickly than the population. Known as the ‘Malthusian trap’, and depicted in Figure 18.4, Malthus argued that the growth in population would drive down output per worker as the economy moves along the production function (from A to B in Figure 18.4). Yet this prediction proved incorrect, precisely because of investment in capital goods and technological change that shifts up the production function itself as in Figure 18.5. Solow growth model ► BVFD: read section 18.5 and Maths A18.1. This section discusses how capital accumulation is important for sustained economic growth. In particular, the second part of section 18.5 introduces the Solow growth model, one of the most used models in all of macroeconomics, which provides major insights into some of the mechanisms at work in the growth process. This model was initially 144 Block 12: Supply-side economics and economic growth developed in the mid-1950s by the American economist Robert Solow, working at MIT. Solow received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1987 for his contribution to growth theory. Although the textbook describes this model (in particular in the two diagrams 18.5 and 18.6 and Maths A18.1), it is laid out in more detail below. This should help to make the exposition clearer so you can gain a thorough understanding of this important model. The Solow model starts with a simplified production function including just capital (K) and labour (L). Labour can be defined to include human capital; for simplicity, no distinction is made between the total population and the labour force; also, for simplicity’s sake, land (including raw materials) is considered as fixed and is not included. Y = Af(K, L) As stated above A can be thought of as a representing technology and changes in A as representing technical progress; higher A makes both labour and capital more productive (A is sometimes said to represent total factor productivity). Two key assumptions of this model are that there are constant returns to scale (CRS) and diminishing marginal productivity of capital (MPK).CRS means that if we multiply K and L by a constant, then Y is also multiplied by that constant. Hence, multiplying by 1 L enable us to write the production function in the ‘per worker’ version: ( Y K = Af ,1 L L ( Ignoring the constant 1 and defining per capita output as and the capital per worker as , we can express the production function in ‘per worker’ terms: y = Af (k) This is illustrated in Figure 18.5 of BVFD – the green line shows the path of income against capital per worker and is concave because of the decreasing MPK. Adding more capital per worker, k, increases output per worker, y, but with diminishing returns. A slightly fuller version of that diagram is presented here as Figure 12.2. This enables us to analyse the Solow model in a bit more detail. The per worker production function is represented by the curve labelled y. This production function represents the supply side of the model. The demand side is represented very simply by the equation Y = C + I, as we saw in Block 11 (assuming G = NX = 0). Let us further assume a constant marginal (and average) propensity to save of s. This tells us a fraction s of income is saved and the rest consumed, so we can substitute C = (1 – s)Y. Dividing through by L again we have: y = (1 – s)y + i Where denotes investment per capita. Solving gives: i = sy = sAf(k) (recall that savings equals investment in a closed economy). This investment schedule is also shown in Figure 12.2 and by the orange line in BVFD Figure 18.5. The dotted line from k* up to the green line represents output at that level of capital per worker (y*). This can be divided into investment (below point E) and consumption (above point E). 145 EC1002 Introduction to economics This is the basic model. It is very simple. The production function determines the economy’s output and the consumption function determines how this output is divided between consumption and investment. There is one additional feature which is important; the Solow model makes the growth of the economy’s capital stock endogenous to the model. Investment increases the capital stock (capital deepening), while depreciation of capital reduces it (equipment that wears out and needs to be replaced). Let δ be the depreciation rate i.e. the proportion of the capital stock that wears out each year. Thus: ∆K = I – δK Dividing through by L, this can be written in per-worker terms: ∆k = i – δk = sy – δk = sAf(k) – δk (This is equivalent to equation (1) in Maths2 A18.1, though there is no explicit parameter A). For the capital stock to be constant we require ∆k = 0, i.e. i = δK. We call this position the steady state. If is not constant, but is growing (due to population growth or immigration) at a constant rate n, then in order to keep the capital per worker constant not only does worn out capital have to be replaced but additional investment is required to provide capital for the new workers resulting from population growth; so now for ∆k = 0 we require: i = (δ + n)k In Figure 12.2 this is shown by the straight line with slope (δ + n). The (δ + n)k line depicts the amount of investment that is required for capital per worker to remain constant when there is population growth and depreciation; in this sense, one can think of this as ‘break-even’ investment. Having put the elements of the model in place, we can look at its long-term equilibrium and what happens when the economy is not at the equilibrium. Suppose the economy is at k1 in Figure 12.2. Investment is greater than needed to offset depreciation plus population growth, so the capital stock (per worker) increases. It will go on increasing until i = (δ + n)k (i.e. until new investment exactly offsets depreciation and population growth). Of course, as k increases, so does y (via the production function). Therefore, knowing the steady state level of capital per worker, k*, also gives us income and consumption per worker. In Figure 12.2, income per worker is given by the point where the dotted line rising vertically from k* meets the production function and is indicated on the diagram as y*. Consumption per worker is the gap between income and savings. When i = (δ +n)k we are at the steady state and so the capital stock per worker does not change, nor does output per worker. We call these steady state levels of capital and output per worker k*, y* respectively. To make sure you understand how the economy always moves to the steady state trace out what happens when k > k*. So, in spite of its name, the long-run equilibrium in the Solow growth model is characterised by constant output per worker and capital per worker (with n = 0 the steady state levels of Y and K, not just per worker, will also be constant). Growth occurs in the transition to the steady state (or to a new steady state if something previously held constant changes). While we don’t prove it formally here, an important aspect of transition dynamics is that the further below its steady state output an economy is the more rapidly it will grow (towards it). An analogous result applies if y > y*. 146 Note: Δk (used above) denotes the change in capital between two periods, such as two months or two years, while (used in Maths 18.1) denotes the continuous rate of change in capital. 2 Block 12: Supply-side economics and economic growth (δ + n)k y, δ, i y y* i = sy consumption net investment depreciation k1 k* k Figure 12.2: The Solow model. Shifts in the parameters will shift the relevant lines and lead to a different steady-state rate of capital per person. The savings rate plays an important role in the Solow model, but it is important to understand the exact nature of this role. For a given production function, a higher propensity to save results in higher k* and y*. As can be seen in BVFD Figure 18.6, a higher savings rate s shifts the savings/investment line upwards (but not the y curve). This leads to a higher steady state level of capital per worker and a higher output per worker. On the other hand, a higher rate of population growth or depreciation will shift the breakeven investment line upwards, leading to a lower steady state capital per worker and lower output per worker. Thus, the Solow model predicts that countries with high savings rates and low rates of population growth will tend to have higher per capita income. To some extent, this is empirically corroborated. Activity SG12.2 Use a graph to demonstrate how an increase in the rate of population growth can lead to changes in the long-run level of per capita output. Will this affect the long-run per capita growth rate? Technical progress ► BVFD: read section 18.6. Although the Solow model provides some useful insights, the basic model discussed in the previous section predicts that the rate of per person output growth tends to zero (i.e. at the steady state, growth in per capita output is zero). Yet this is not what is observed in practice in the developed industrial economies. What could possibly explain long run growth? Extending the Solow model to include technical progress is key to explaining long-run growth and the improvement in living standards over generations. 147 EC1002 Introduction to economics We can do this in two ways. Firstly, there is the possibility of growth in parameter (total factor productivity). Growth of this parameter reflects Hicks neutral technical progress, which means that the entire production function shifts upwards. That is, the economy is more productive in combining capital and labour to produce goods and services in general. If this happens once, then the economy transitions to the new steady state and again there is no long term growth in per capita income. However, if total factor productivity grew at a constant rate, the steady state would keep changing giving rise to growth.. Activity SG12.3 Use a graph to demonstrate how an increase in total factor productivity can lead to changes in the long-run level of per capita output. Will this affect the long-run per capita growth rate? What if total factor productivity rises at a constant rate annually? Another possibility is labour augmenting technical progress. Let us explain more clearly what is meant by labour augmenting technical progress. Consider the labour input to the production function. We have written this as where is the number of workers. In practice, however, we are concerned not just with the number of workers but with their productivity. So, we can think of the labour input as being the product L × E (henceforth ), where E is efficiency per unit of labour. So LE is units of effective labour (worker-equivalents in BVFD), not just a head count of workers. Now suppose that due to technical progress E is growing at a rate t. Hold L constant to keep things simple. Effective labour is growing at the rate of technical progress, t. If we were to redefine y, and k as output and capital per unit of effective labour then the steady state equilibrium would have constant y* = Y * LE and k* = K * LE For the capital stock per effective worker to be constant, investment is needed not just to cover depreciation and population growth but to supply the extra units of effective labour with capital to work with – failure to do this would result * in reductions in capital per unit of effective labour. Note now that if Y LE is constant, then with L constant and E growing at a rate t, Y* and Y * L must also be growing at a rate t. Hence, with technical progress the Solow model can produce long-run growth in per capita output. If we drop the assumption that population and the workforce are constant, output per worker still grows at t, but total output, Y, in the steady state grows at t + n. This extended model is depicted in BVFD Figure 18.7 (for the case where δ = 0). The two differences to the diagram now that technical change has been added is that the break-even investment line has the slope (t + n)k and that all variables are now measured per unit of effective labour or per worker-equivalent, not per worker. Since the technological progress was assumed to be labour augmenting, labour productivity has increased. Investment at the rate (t + n)k now ensures that steady state capital per worker-equivalent, and hence output per worker-equivalent, are constant. Since worker-equivalents grow at rate t + n and workers grow at rate n (which is slower – since t is a positive number), output per worker and capital per worker are increasing at rate t. With technical progress, there is a steady state level for output and capita per worker-equivalent, but output and capital per worker continue to grow at a positive rate over time. Thus, the Solow model provides good insights into factors leading to high levels of output per capita (high saving rate (s), high total factor productivity (A), low depreciation (δ). Growth or decline will occur due to transition dynamics when something shocks the economy away from 148 Block 12: Supply-side economics and economic growth its steady state. The model is less successful at explaining long run growth in per capita output (income), unless ongoing technical progress can generate such growth. However, as BVFD point out, the fact that there is no examination of where technical progress comes from – it is simply assumed – the model is unsatisfactory. This shortcoming is what modern endogenous growth theory attempts to rectify, but before turning to that section 18.7 of the text provides some more empirical background on economic growth. OECD and growth ► BVFD: read section 18.7 and case 18.2 and complete activity 18.1 Looking at economic growth for different countries over time shows complex patterns. There is no single, overarching path that every country takes and can be easily described and predicted. Context matters. That is why this section and case 18.2, although interesting, may seem somewhat inconclusive – the OECD countries have experienced episodes of faster and slower growth, depending on an array of factors, and the convergence hypothesis has both examples which support it and examples which lead many to question it. Some commentators would also question whether the post-1973 slowdown in productivity growth really is a cyclical short run phenomenon as BVFD argue or whether it represents a more seismic change. There are many unanswered questions in this still developing field. Nonetheless, the models that have been proposed and the improved data that have been becoming more available have provided insights into important factors behind the growth (or stagnation) of countries at different times. Some of the factors mentioned in this section and the case box include: historical levels of capital and output; growth in inputs – labour, capital and human capital; productivity growth; technical progress; the spread of technology; trade openness; absence of internal strife; a country’s social and political framework; and supply shocks. Some of these lie outside the sphere of influence of a domestic government, while others can be influenced by social movements and policy decisions. Activity 18.1 should be a good guide to whether you have properly understood the Solow model. Romer’s model of endogenous growth ► BVFD: read section 18.8. One of the critiques of the Solow model is that long-term growth comes from the rate of technical change, which is assumed rather than endogenous to the model. In order to generate long-run growth we need accumulation of something in the production function, but which is not subject to diminishing returns. This section discusses endogenous growth and Romer’s model, which is sometimes known as the AK model. You are not required to know formal equations of the Romer model beyond what is below. A discussion of the key assumptions and insights of the model are what you should focus on. Up to now we assumed a production function with diminishing marginal returns to increases in the capital stock, which is why the production (and savings) curves were drawn as concave to the origin in previous sections. In contrast, the endogenous growth model proposed by Paul Romer does not assume diminishing returns to capital, but rather constant returns to capital, such that: Y = AK 149 EC1002 Introduction to economics where output is proportional to capital. A represents Hicks neutral technology or total factor productivity as before and can be held constant in very basic endogenous growth models. Dividing through by gives the production function in per capita terms. y = Ak We note that it is linear, rather than concave, due to the fact that it is not subject to diminishing returns (MPK = A). This allows us to draw a new diagram where we see growth is ongoing: Output/ worker y sy y1 (δ + n)k k1 Capital/ worker Figure 12.3: The Romer model But why does the return to capital not diminishing? What is the intuition behind this representation and is it reasonable? If K includes ideas and knowledge (instructions, recipes, management techniques) as well as objects (machines, buildings, workers, etc.) then it may well be reasonable that K doesn’t run into diminishing returns. This is partly due to the public goods nature of ideas – they are non-rival (although sometimes excludable by patents and the like – recall the discussion of public goods in Block 10). If one firm uses a given technique to produce an industrial product, or a formula to produce a medical drug, that technique, that formula, is not used up – it is available for other firms to use also. If one firm introduces ‘just-in-time’ inventory control that technique is still available to other firms. One simple characterisation of constant marginal product of K is that as countries become richer and increase physical capital, they simultaneously increase investment in human capital; the increase in the ‘ideas’ component of K offsetting any tendency to diminishing marginal returns in the ‘objects’ component of K. Costs of growth ► BVFD: read section 18.9 and case 18.3 Growth in output and consumption is often associated with resource depletion and environmental problems. At the same time inequality has risen dramatically in recent decades as countries have grown. Focus is now on promoting ‘sustainable growth’ and lowering inequality, which are included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. 150 Block 12: Supply-side economics and economic growth Overview This block starts by discussing supply-side economics. Supply-side policies aim to improve an economy’s productive potential. Higher labour input and increases in labour productivity are important elements of supply-side economics as are increased flexibility in product or labour markets and improved competitiveness. Although policies which boost aggregate supply are desirable, in practice this may be difficult to achieve. Second, this block examines long-term economic growth. Economic growth is most commonly measured by real GDP or real GDP per capita. Even small annual changes in economic growth can lead to huge changes in living standards in the long term. Potential output can be increased either by increasing the inputs of land, labour, capital and raw materials, or by increasing the output obtained from given input quantities. Technical advances are an important source of productivity gains, and can be fostered for example through subsidised research in universities and the provision of patents for companies that make new discoveries. The simplest theory of growth, as characterised in the Solow growth model, has a steady state in which capital, output and labour all grow at the same rate. Whatever its initial level of capital, the economy converges on this steady state path. This theory can explain output growth but not growth in output per worker (productivity growth). Labour augmenting technical progress allows permanent growth of labour productivity. Convergence theory argues that countries will converge, both because capital deepening is easier when capital per worker is lower and because of catch-up in technology. There have been several examples of this in recent decades, where developing countries have grown much faster than developed countries, though not all countries fit into this pattern. Institutional frameworks impact on the adoption of new technology, which strongly influences growth rates. Theories of endogenous growth are built on the assumption of constant returns to capital. If this assumption holds, the long-run growth rate of productivity can be influenced by choices about saving and investment, providing incentives for government to support investments in education, training, physical capital and innovation. Although economic growth is associated with improved living standards, it doesn’t necessarily measure happiness (recall ‘Food for thought Box 4’ in Block 11). Furthermore, continual increases in output and consumption today have severe consequences for the environment and for future generations. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. 151 EC1002 Introduction to economics Sample questions Multiple choice questions 1. ‘Capital widening’ refers to that part of investment needed to: a. increase the per capita capital-labour ratio b. replace capital that has depreciated c. equip new units of labour at the same capital–labour ratio d. do all of the above. 2. Real GDP tends to understate income in developing economies by: a. underestimating saving b. ignoring government deficit spending c. omitting non-market transactions d. all of the above. 3. Convergence implies that: a. rich nations will grow faster than poor nations b. the rich will get richer and the poor will get poorer c. the rich will get poorer and the poor will get richer d. poor nations will grow faster than rich nations. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Growth is always desirable. 2. In the absence of technical progress the economy converges to a state in which output per worker always increases. 3. In the absence of technical progress an increase in the saving rate results in a steady state with higher output per worker. Long response question 1. a. Starting with two production functions, show the difference between the key assumptions of the Solow model with technical progress and Romer’s model of endogenous growth. b. What is the long-run growth rate of per worker output implied by each model and what are the implications of this for government? c. In a model without technical progress, use a diagram to demonstrate how an increase in the rate of population growth can lead to changes in the long-run level of per capita output. Will this affect the long-run per capita growth rate? 152 Block 13: Output and aggregate demand Block 13: Output and aggregate demand Introduction In Block 12 we studied the determinants of potential output and the dynamics for growth in living standards. We now shift our focus to the difference between actual output and potential output. While potential output tends to increase steadily over time, actual output tends to fluctuate strongly, sometimes growing faster than potential output and sometimes growing slower or even decreasing. Much of macroeconomics is concerned with modelling the gap between actual and potential output and understanding shorter run fluctuations in economic activity and the effects of macroeconomic policy in managing those fluctuations. In Block 13, we start to develop a model of the determination of output, which will be developed further over the rest of the macroeconomic blocks. In blocks 13 to 15 we operate under a basic assumption that the price level is constant (i.e. there is no inflation). We then relax this assumption. To start with, the focus is on demand and actual output is assumed to be demand-determined. Aggregate demand is defined initially as planned or desired spending and short-run equilibrium is defined as the point where aggregate demand is equal to actual output. In the Block 11 we saw that income and output can be defined as Y = C + I + G + NX. In equilibrium, output and aggregate demand are equal, hence Y = AD = C + I + G + NX. Chapter 16 goes into more detail on consumption (C) and investment (I), while Chapter 17 looks at government spending (G) and net exports (NX). One very important concept in this block is the multiplier, which shows how much equilibrium output changes due to a change in aggregate demand. You will need to understand this, be able to calculate it and show how it is affected by changes in consumption behaviour, taxation and imports. In macroeconomics, there are two major policy instruments available to the government: fiscal policy and monetary policy. Fiscal policy has to do with government spending, taxation and the budget. By the end of this block, you should have a good understanding of fiscal policy, including its limitations. The analysis in these two chapters is best understood by use of graphs, in particular, the consumption function, the aggregate demand schedule, and graphs of leakages against injections. You will also need to understand the meaning of the 45-degree line (along which the values on the x-axis are equal to the values on the y-axis) and how this can be used to indicate equilibrium, as well as inflationary and deflationary gaps. You will need to learn these graphs and practise drawing them. They are the building blocks you will need in later analysis. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • contrast actual output and potential output • show how aggregate demand determines short-run equilibrium output • explain inflationary and deflationary gaps • define the marginal propensity to consume c and the marginal propensity to import z 153 EC1002 Introduction to economics • analyse consumption demand, investment demand, foreign trade and equilibrium output • calculate the multiplier and the balanced budget multiplier • explain the paradox of thrift • analyse how fiscal policy affects aggregate demand • evaluate the limits to discretionary fiscal policy as well as automatic stabilisers • explain the structural budget and the inflation-adjusted budget. • discuss how budget deficits add to national debt. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapters 16 and 17. Synopsis of this block This block covers two chapters from the textbook. Chapter 19 explores aggregate demand, focusing on the components consumption and investment, and examines equilibrium output, which is assumed to be demand determined at this stage. Another important concept is the multiplier, which shows by how much changes in autonomous demand lead to even greater changes in output. In the simple model presented 1 in this chapter, the multiplier is equal to 1–c , where c is the marginal propensity to consume. Chapter 20 goes on to examine the other two key components of aggregate demand, namely government spending and net exports. Government decisions on spending, together with taxation, make up the government’s fiscal policy. This is one of the two main macroeconomic policy tools (the other is monetary policy). This block discusses various aspects of fiscal policy, including the balanced budget multiplier, the fiscal stance, and automatic stabilisers, as well as the implications of deficits for national debt. This chapter also examines the impact of imports and exports on national income. Having included 1 these two sectors, the full multiplier becomes 1–c(1–t)+z where t is the proportional net tax rate, c is the marginal propensity to consume and z is the marginal propensity to import. ► BVFD: read the introduction to Chapter 19, case 19.1, sections 19.1 and 19.2 and concept 19.1. Components of aggregate demand: consumption and investment Chapter 19 of BVFD looks at a closed economy with no government. (An economy is closed if there are no imports and exports.) There are two components of aggregate demand, consumption and investment. The national income identities are Y≡C+I which is aggregate demand, and Y≡C+S which is what consumers use their income for. This implies I ≡ S, investment must equal saving. This is an identity, it must always hold. Equilibrium requires that planned investment is equal to planned saving. For example, suppose the only good consumers consume is cars. The car manufacturer decides how many cars to produce at the start of the year. Consumers decide how many cars to buy at the end of the year. If 154 Block 13: Output and aggregate demand consumers demand fewer cars than are made, the unsold cars are an unplanned investment in inventory. • Consumption – has to do with households and includes durable goods (e.g. cars), nondurable goods (e.g. clothing) and services (e.g. getting a haircut) • Investment – mainly has to do with firms and can be defined as spending on capital (i.e. fixed assets used in future production). It includes business fixed investment (such as spending on plants and equipment), residential fixed investment (which is spending by consumers and landlords on new housing units) and inventory investment (which is the change in the value of all firms’ inventories). Activity SG13.1 a. Draw the consumption function. What does the intercept mean? What does the slope indicate? b. Interpret the meaning of the following identities: Y≡C+S MPC + MPS ≡ 1 Equilibrium output ► BVFD: read section 19.3 and complete activity 19.1. It is important to understand that in the short-run equilibrium, actual output equals the output demanded by households as consumption and by firms as investment. Thus in short-run equilibrium, actual output and actual income are equal to aggregate demand (desired spending). In a graph of desired spending against output and income, drawing a 45-degree line from the intersection of the x and y-axis shows all of the points where desired spending and output (and income) are equal. Where the aggregate demand function crosses this line, we can find the short-run equilibrium point. This diagram (Figure 19.6) is known as the Keynesian cross. ► BVFD: You must read and understand Maths 19.1. Some people find the algebra easier to understand than the diagram. What is the mechanism by which the economy is brought into short-run equilibrium? Running down inventories (i.e. unplanned destocking), or the reverse – making unplanned additions to inventory, can move the level of output to the short-run equilibrium level. Output equals expenditure because unsold output goes into inventory and is counted as ‘inventory investment’ whether or not the inventory build-up was intentional. In effect, we are assuming that firms purchase their unsold output. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that nothing guarantees that the short-run equilibrium is the level of potential output. Potential output is the economy’s output when inputs are fully employed. ► BVFD: read case 19.2 – how did the financial crash affect the economy in the country where you live? Also read section 19.4. Planned investment equals planned savings only in equilibrium. Draw the savings and investment functions and indicate the equilibrium output level. What is the mechanism that brings the level of output back to equilibrium, such that planned investment and planned savings are equal? 155 EC1002 Introduction to economics Activity SG13.2 Using the following savings and investment functions, calculate the equilibrium level of output Y and the level of planned saving and planned investment. Draw a diagram. S = –5 + 0.3Y I = 55 ► BVFD: read Maths 19.1. This maths box shows why planned investment equals planned savings. Read it through and then, without looking at the textbook, use the following equations to show that planned investment equals planned savings: Y = AD = C + I (in equilibrium) C = A + cY S=Y–C The multiplier ► BVFD: read sections 19.5 and 19.6 and concept 19.2. These sections introduce the concept of the multiplier. A change in autonomous spending will result in an even greater change in equilibrium output. The multiplier shows by how much greater the change in equilibrium output will be, relative to the initial change in autonomous spending. At this stage, the multiplier (which equals 1/[1 – c] or equivalently, 1/s) only depends on the marginal propensity to save. In later chapters when we add in the government and overseas sector, the multiplier will also depend on taxation and imports, since these are also leakages from consumption, just like savings. Coming back again to Maths box 19.1 – equilibrium demand is autonomous demand multiplied by the multiplier. The following question should now be very straightforward: Activity SG13.3 Given, C = 10 + 0.5Y, calculate the equilibrium output when I = 20. Now check that Y = AD = C + I in equilibrium. The paradox of thrift ► BVFD: read section 19.7 and case 196.4. This is the interesting result that a change in the amount households wish to save at each income level leads to a change in equilibrium income, but no change in equilibrium saving, which still equal planned investment in equilibrium. The role of confidence ► BVFD: read section 19.8 and concept 19.3. Business confidence plays a major role in global markets and is largely determined by news or beliefs about the future. The emotion that drives business and consumer confidence is sometimes also known as ‘animal spirits’, a term used by John Maynard Keynes in The general theory of employment, interest and money (1936). 156 Block 13: Output and aggregate demand ► BVFD: read the Summary and attempt the revision questions of Chapter 19. Fiscal policy: government spending and taxation BVFD sections 20.1–20.6 introduce the government. All this material is very important and must be studied carefully. As you know, Y = C + I + G + NX. Having examined consumption and investment, we now introduce government spending and net exports. ► BVFD: read sections 20.1 and 20.2 as well as Maths 20.1. The argument in BVFD 20.2 is graphical and algebraic. You may find it helpful to see it in algebra. In a closed economy aggregate demand consists of three things, consumption C, investment I and government expenditure G. Remember to begin with the situation with no government. Aggregate demand is C + I. Consumption is given by the consumption function .The consumption function gives C = A + cY, where A is autonomous demand and c is the marginal propensity to consume. It is assumed that A > 0 and 0 < c < 1. It follows that: Y = C + I = A + cY + I implying that Y= A+I (1 – c) where 1/ (1 − c) is the multiplier. At this stage in the argument, A and I are autonomous. They vary, but there is no description of why and how they vary in the model at this stage. The model tells you the effects of variation in A and I on aggregate demand. Now we introduce the government. Aggregate demand is Y ≡ C + I + G, where G is government expenditure. Households use their income to consume, save and pay taxes so Y ≡ C + S + T. The accounting identity is C+I+G=C+S+T so G−T=S−I. The gap between savings and investment S − I is equal to the government deficit G – T. Another way of looking at this is that S≡I+G+T This is an identity. Savers can do two things: they can lend money to firms which use it for investment or they can lend it to the government to cover the deficit. Equilibrium requires that planned saving is equal to planned investment + the planned government deficit. Suppose to begin with that the government decides how much to spend G and the total amount of tax they want households to pay T. Households spend out of their income after tax Y − T and the consumption function is C = A + c(Y – T). Then Y = C + I + G = A + c(Y – T) + I + G A, T, G and I are treated as autonomous. Then (1 – c) Y = A + I + G – cT . 157 EC1002 Introduction to economics Hence: Y= A + I + G – cT (1 – c) The multiplier is on government expenditure is 1/ (1 − c). Now suppose that instead of deciding on total tax revenue government sets the tax rate t; for every additional pound that the household earns it pays extra tax £t. After tax income is (1 − t)Y and the consumption function is A + c (1 − t)Y. Aggregate demand is Y = C + I + G, so Y = C + I + G = A + c(1 – t)Y + I + G so (1 − c(1 – t))Y = A + I + G Y= A+I+G 1 – c(1 – t) The multiplier is now 1/ (1 − c (1 − t)) which is smaller than the multiplier with no government 1/ (1 − c), but remains greater than 1. What is the intuition behind this? Fiscal spending increases aggregate demand and thus income but with proportional taxes this induces a higher tax bill increasing leakages. The arithmetic example in BVFD section 20.3 discusses a situation which BVFD call the ‘balanced budget multiplier’. This is not the usual meaning of the term balanced budget multiplier, and you should not read the arithmetic example they provide. The standard model with a balanced budget multiplier assumes that government expenditure G = T = tax revenue so consumption C = A + c(Y − G). Then Y = C + I + G = A + c(Y – G) + I + G so (1 – c)Y = A + I + (1 – c)G so Y= A+I +G (1 – c) expenditure is 1. This is the balanced budget multiplier. Output increases with G even though the budget is balanced. Activity SG13.4 Draw the aggregate demand schedule with and without the government sector given the following parameters: C = 200 + 0.6YD I = 300 G = 200 t = 0.3 What is the change in equilibrium output? 158 Block 13: Output and aggregate demand The budget ► BVFD: read section 20.4 to 20.6 as well as concept 20.1. Complete activity 20.1. Activity SG13.5 Complete the following table. Three ways of reducing debt as a percentage of nominal GDP: Grow Your Way Out Create Inflation Default Explanation: Explanation: Explanation: Historical example: Historical example: Historical example: Recommended approach? Recommended approach? Recommended approach? Foreign trade: exports and imports ► BVFD: read section 20.7. This introduces the fourth sector in our circular flow model: the rest of the world. We now have the complete equation: In equilibrium, Y = AD = C + I + G + X – M ► BVFD: read Maths A20. The full multiplier, taking into account all leakages savings, taxation and imports, is lower than in the simple, two-sector model, at 1/[1 – c(1 – t) + z]. Activity SG13.6 Show the full multiplier for an open economy 1/[1 – c(1 – t) + z] is equivalent to can equivalently be expressed as the 1/[t+s (1 – t) + z]. This activity showed that 1/[1 – c(1 – t) + z] = 1/[t + s(1 – t) + z]. These two expressions of the full multiplier (for an open economy with government) show how including the additional sectors reduce the size 159 EC1002 Introduction to economics of the multiplier compared to an economy with just households and firms (where the multiplier is simply 1/[1 – c] = 1/s). While a closed economy with no government sector has only one leakage – savings – an open economy with government has three leakages – savings, taxation and imports. In both cases, the multiplier is calculated as the inverse of the marginal propensity to withdraw. The lower the marginal propensity to withdraw (lower savings rate, lower marginal tax rate, lower marginal propensity to import), the greater the final increase in income that will result from additional spending. ► BVFD: read the summary and complete the review questions. Overview This block examines the components of aggregate demand, as well as how aggregate demand determines output, based on the multiplier effect. Aggregate demand is defined in this block as planned or desired spending and short-run equilibrium is defined as the point where aggregate demand is equal to actual output. In equilibrium, output and aggregate demand are equal, hence Y = AD = C + I + G + NX. Chapter 19 of the textbook examines consumption and investment. Consumption consists of autonomous consumption (at zero income) plus the proportion of income that is spent rather than saved. This proportion is represented by the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). Investment is treated as constant. When prices and wages are fixed, the goods market is in equilibrium when planned spending equals actual spending and actual output (not potential output). In equilibrium, planned saving equals planned investment. When the goods market is not in equilibrium, companies’ inventory levels will change to restore equilibrium – either through unplanned disinvestment (reductions in inventories) or unplanned investments (increases in inventories). Changes in inventory send a signal to firms to increase or decrease future output levels. Such changes in planned investment lead to greater changes in equilibrium output, due to the multiplier effect. In its simplest form, the multiplier is equal to 1/(1 – MPC). Chapter 20 of the textbook examines the government spending and net exports components of aggregate demand/output. The government levies taxes and buys goods and services. Taxes reduce private disposable income and hence consumption. Government spending raises aggregate demand and equilibrium output. An equal increase in government spending and taxation leads to an increase in aggregate demand and output, which is known as the balanced budget multiplier. Government decisions regarding spending and taxation are known as fiscal policy. Fiscal policy can either be expansionary or contractionary, in practice however, fiscal policy cannot completely stabilise output. The budget deficit is a poor indicator of the government’s fiscal stance, because it is not only influenced by discretionary policy decisions, but also by economic conditions. Automatic stabilisers such as unemployment benefits act to reduce fluctuations in GDP. Budget deficits add to the national debt. The final element of the equation is net exports. Exports raise aggregate demand and can be viewed as autonomous. Imports are a leakage and are assumed to rise with domestic income. Both taxes and imports reduce the effect of the multiplier. In the full model, the multiplier is equal to 1 1 = [1–c(1–t)+z] [t+s(1–t)+z] . In equilibrium, desired leakages (S + NT + Z) must equal desired injections (G + I + X). 160 Block 13: Output and aggregate demand Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. Which of the following statements is false? a. Actual saving is always equal to actual investment. b. Planned saving is always equal to planned investment. c. Firms adjust their inventories which ensures that saving and investment are equal. d. Consumers must sometimes adjust their savings patterns so that saving and investment are equal. 2. Potential output is: a. The maximum an economy could conceivably make. b. The output when every market in the economy is in long-run equilibrium. c. The amount of production a country is striving for through technological innovation. d. The output when there are no unemployed workers. 3. In the model of national income determination investment, government expenditure, and tax revenue, are all taken to be exogenous. A more sophisticated model recognises that there are automatic stabilisers. Which of the following statements about the model with automatic stabilisers is correct? a. Tax rates must change for automatic stabilisers to work. b. In the model with automatic stabilisers tax revenue automatically falls when national income increases. c. In the model with automatic stabilisers government expenditure automatically increases when national income increases. d. The multiplier is lower in the model with automatic stabilisers than it is in the model without automatic stabilisers. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Consider a closed economy with no government. Assume that consumption is given by C = A + cY and Y = C + I where A is a positive constant and 0 < c < 1. If saving and investment are at their planned levels and S = I then the economy is in equilibrium. 2. In a closed economy with no government consumption is given by C = A + 0.75Y. Hence the multiplier is also 0.75. 3. Assume that consumption is given by C = A+c(Y–T) and Y = C + I + G where A is a positive constant and 0<c<1. If consumers become more willing to consume out of disposable income (so c increases), then income must fall. 161 EC1002 Introduction to economics Long response questions 1. The country of Researchland has been recently founded. It started as a simple economy with no government. The country will then elect its government and will finally become open to trade. This question guides you through the formation of the country. a. When Researchland is a closed economy with no government we know that: C = 100 + 0.4Y I = 300 Draw the aggregate demand (AD) scheduled and find: i. the multiplier, ii. the equilibrium level of income, iii. the budget deficit or surplus and the trade balance. b. The citizens of Researchland elect a government acting according to the following equations: G = 200 t = 0.2 Draw the aggregate demand (AD) scheduled and find: i. the multiplier, ii. the equilibrium level of income, iii. the budget deficit or surplus and the trade balance. c. Researchland now opens its borders to trade. The following data describes the patterns of trade: X = 300 z = 0.4 Draw the aggregate demand (AD) scheduled and find: i. the multiplier, ii. the equilibrium level of income, iii. the budget deficit or surplus and the trade balance. 162 Block 14: Money and banking; interest rates and monetary transmission Block 14: Money and banking; interest rates and monetary transmission Introduction This block introduces an economic approach to the analysis of money. The ultimate aim of this block is understanding how monetary policy works. There are two types of policy here. Traditionally, monetary policy worked by controlling the monetary supply, and was based on two beliefs about the way that monetary policy works. The first belief is that it is possible for central banks to control the money supply. The second was that central banks should target the rate of growth of the money supply because that determines the rate of inflation. Things are now different, so for EC1002 you need to know very little about the traditional theory of money supply. The way the financial system now works makes it extremely difficult to control the money supply, and central banks have largely given up trying to do so. The central banks of the UK (Bank of England), the USA (Federal Reserve, often called the Fed) and the Euro Area (European Central Bank, ECB) all have an inflation rate target. They are also concerned with the level of output. They implement monetary policy by setting the interest rate. Since the financial crisis they have also used quantitative easing, which is explained in BVFD 22.6. Singapore does monetary policy very differently, targeting the exchange rate rather than the inflation rate (a topic discussed later in the course). A recent innovation that has arisen from the digital revolution is blockchain and cryptocurrencies. You can read more about this in case 21.1 and in Food for thought Box 5 ‘Is bitcoin money?’ Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • explain the medium of exchange and other functions of money • explain how banks create money • differentiate between liquidity crisis and solvency crisis • define narrow and broad money • identify motives for holding money • discuss how money demand depends on output, prices and interest rates • describe the central bank’s role in influencing the money supply and in financial regulation • describe money market equilibrium • discuss intermediate targets and the transmission mechanism of monetary policy • describe how a central bank sets interest rates and how interest rates affect consumption and investment demand. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapters 21 and 22 (excluding Maths A21.1 and Maths A22.1). 163 EC1002 Introduction to economics Synopsis of this block Chapter 21 of the textbook starts by introducing money and its functions – as a medium of exchange, a store of value, a unit of account and a standard of deferred payment. The way that banks create money is described. The demand for money relates to people’s motives for holding money rather than interest-bearing financial instruments such as bonds. The quantity of real money demanded falls as the interest rate rises. Higher real income raises the demand for real money at each interest rate. Chapter 22 introduces the role of central banks, especially the Bank of England, and the instruments available to the central bank in influencing the supply of money. This chapter also examines money market equilibrium. Finally, the targets and instruments of monetary policy are introduced, as are the transmission mechanisms for how these impact on the real economy. Money and banking ► BVFD: read sections 21.1–21.3 and the final part of 12.4, ‘Measures of money’. The bank deposit multiplier is the ratio of broad to narrow money. The information contained in these four sections is useful background knowledge. Read the sections through carefully and test your understanding with the following quick questions: • What are the main functions of money? • How do banks make profits? • How do banks create money? Financial crises ► BVFD: read section 21.6 and case 21.2. If you are interested in learning more about the causes of the financial crisis, there is a great deal of information online, including several documentaries which have been made about it, such as ‘Inside Job’ (2010). You may also want to research the changes to regulation that have been implemented and are still being implemented in many economies worldwide as a result of the crisis. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the revision questions. Demand for money ► BVFD: the introduction to Chapter 22 and section 22.1. This section discusses the demand for money and explains the three main reasons people hold money rather than storing all their wealth in interestbearing assets such as bonds. These three reasons are the transactions motive, the precautionary motive and the asset motive. 164 Block 14: Money and banking; interest rates and monetary transmission Activity SG14.1 What will happen to the demand for money in the following cases, assuming all other factors remain constant? a. Real incomes fall (say, because of a recession). b. There is a general rise in prices. c. Interest rates fall. Money market equilibrium and monetary control ► BVFD: read sections 22.2–22.3. Historically the money market was modelled with central banks controlling the nominal money supply. With fixed prices this also implies control real money balances, assuming a stable money multiplier. Thus real money supply was drawn as a vertical schedule, as in Figure 22.1, with a downward sloping money demand schedule (LL), such that the interest rate adjusts to equilibrate the market. Yet this representation of the money market doesn’t accurately describe the fact that modern central banks set the interest rate rather than target money supply. If we model the central bank as fixing the interest rate then they must supply whatever money supply is demanded for selected interest rate to prevail. The money supply in circulation is thus pinned down by the LL schedule, given the target. This is illustrated in Figure 22.2. Monetary policy: targets, instruments and the transmission mechanisms ► BVFD: read sections 22.4 and 22.6. Section 22.4 explores the ultimate objectives of monetary policy, which could include price stability, output stabilisation, influencing the exchange rate etc. The instrument used to achieve the target or objective is the variable over which the central bank makes decision, such as the interest rate. The table below provides a summary of the transmission mechanisms of monetary policy, showing how changes in interest rates and the money supply impact on aggregate demand and output. However, it does not include some important details on the permanent income hypothesis and life-cycle hypothesis, and the link between short-term and long-term interest rates. You can read about these in 22.5 the content and figures will not be directly examinable. Interested students who would like to know more about how QE works can refer to the following articles: www.economist.com/node/21558596 www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2015/03/economistexplains-5 www.bbc.com/news/business-15198789 165 EC1002 Introduction to economics Transmission mechanisms of monetary policy: Y = C + I + G + NX Consumption Investment Wealth Consumer Credit Permanent Income Fixed Capital Inventories Higher real money supply increases wealth directly The credit available to consumers increases Lower interest rates increase wealth indirectly Low interest rates make borrowing for consumption more affordable Consumption demand reflects longrun disposable income. Lower interest rates increase consumption by increasing the present value of expected future labour income Lower interest rates mean more investment opportunities exceed their opportunity cost (with a more powerful impact on long-term investments) Lower interest rates reduce the opportunity cost of holding inventories Complete Activity 22.1. ► BVFD: read the summary and complete the review questions. Overview The four main functions of money are as a medium of exchange, a store of value, a unit of account and a standard of deferred payment. Narrow money, also known as high-powered money or the money base, consists of currency in circulation plus bank’s cash reserves. Broad money (M4), the money supply, includes deposits at banks and building societies. This chapter examines how banks operate, as this helps generate the money supply. Money supply is greater than the money base by a factor known as the money multiplier, which depends on banks’ reserve ratios and the public’s holdings of cash relative to deposits. Moving on to the demand for money, the textbook discusses how people have various motives for holding money, including the transactions motive, the precautionary motive and the asset motive. The cost of holding money is the interest foregone through not holding assets as bonds. The quantity of real money demanded rises as the interest rate falls, and is higher at each interest rate when real income is higher. Banks play an important role in the economy, but this is not without risk. Regarding financial crises arising in the banking sector, it is important to distinguish between liquidity crises and solvency crises. One approach to dealing with the recent financial crisis (quantitative easing) also explored in the textbook. We can bring together demand and supply to discuss equilibrium in money markets. Nowadays, central banks focus on the interest rate rather than setting a specific money supply target. The central bank’s decisions regarding interest rates known as monetary policy. Interest rates are a common instrument of monetary policy, and a common target is price stability (low inflation rates). Changes in interest rates affect the real economy through their impact on consumption and investment. Consumption, because higher interest rates reduce household wealth, make borrowing dearer and reduce the 166 Government Spending Net Exports (Fiscal policy is generally determined independently of monetary policy) (The effect of interest rates on net exports is covered in later parts of the textbook) Block 14: Money and banking; interest rates and monetary transmission present value of future labour income, leading to a fall in consumption. Investment, because higher interest rates mean fewer investment projects exceed their opportunity cost and the opportunity cost of holding inventories increases, leading to a fall in investment. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. All of the following are examples of financial intermediaries except: a. commercial banks b. stock exchanges c. pension funds d. insurance companies. 2. A credit crunch reduces aggregate demand by: a. increasing the exchange rate b. increasing interest rates c. reducing consumption and investment spending d. reducing the money supply. 6. Given a fixed money supply, more competition in banking could lead to: a. an increase in the interest rate paid on bonds b. a decrease in the interest rate paid on bonds c. no change in the interest rate paid on bonds d. a decrease in the interest rate paid on bank deposits. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Central banks with an inflation rate target are not interested in what happens to the output of a country. 2. A fall in real incomes results in a lower demand for money. 3. When the central bank lowers the interest rate it causes a reduction in investments, as the return from financial assets is lower at lower rates. Long response question A farmer’s harvest will be worth £200 if she can borrow £100 worth of fertiliser. The fertiliser needs to be applied now and harvest will take place in six months’ time. There are N savers in the economy, each endowed with £1. Each agent faces a p% chance that there will be an emergency such as they will absolutely need their £1 three months from now. a. Explain why a financial intermediary is needed in this situation. b. What is the minimum value of N such that a financial intermediary can solve the problem of getting money from savers to borrowers? (Hint: it depends on p). 167 EC1002 Introduction to economics c. On the basis of this example, can you see what economists mean when they say banks are engaged in maturity transformation? d. Now for something a bit harder. Instead of p being a fixed number, suppose that p can turn out to be small (with 90% probability) or large (with 10% probability). Can you see a bank run developing in this case? e. What could the role of a central bank be in this case? Food for thought – Box 5: Is Bitcoin money? The continued spectacular rise in price of the original and leading cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, soaring to $60,000 per BTC in February 2021, though falling back to a mere 44 times its initial value in August 2021, has raised the question again: Is Bitcoin money? Could it become money anytime soon? Economists, as opposed to Bitcoin publicists, who have turned their attention to this over the past five years, or so, answer pretty universally ‘no’. In fact, it is the very appealing and eye-catching volatility of Bitcoin as an asset that makes it very difficult for it to fulfil all the functions of money, even to be a moderately stable store of value like gold. Is Bitcoin, in fact, a medium of exchange, the most basic function of money? It is far from universally accepted; analysing the actual usage of Bitcoin through its registers with great care, one study found only a small percentage use it in this way. One-third or more simply hold it as an asset. Even when Bitcoin is used for transactions, prices are not set in BTC but dollars, euros or pounds sterling. Some sellers have sometimes advertised they will take Bitcoin, with great fanfare. A columnist in Forbes Online noted that almost all such vendor offers which received publicity were a gimmick of sorts. (‘Bitcoin is a Cryptocurrency, but is it money?’ 23 March 2021). Is it then ‘a store of value’ – those investors have bought it and put it away after all. Not all ‘asset classes’ are stable stores of value, and Bitcoin certainly is not. The evidence, again, from usage and surveys, confirms that any asset with that degree of volatility does not fit that traditional definition. Of course, too, it is not a unit of account. No one measures their wealth in Bitcoins. Once again, it is the volatility and dramatic change in Bitcoin that simultaneously undermines its use as currency. For more information, read: • Danielsson, J. ‘What happens if bitcoin succeeds?’ VOX EU, February 2021. 168 Block 15: Monetary and fiscal policy Block 15: Monetary and fiscal policy Introduction Block 13 discussed the goods market while Block 14 covered the money market. This block introduces a framework called the IS–MP model which brings these two markets together in a basic general equilibrium analysis, that is, it analyses the requirements for the goods and money markets to be simultaneously in equilibrium and how this simultaneous equilibrium is affected when certain factors, initially held constant, are allowed to change. The IS-MP model is a simple and effective model for examining the two key tools of demand management – fiscal and monetary policy. After completing this block, you should understand how the combination of these two policies (i.e. the ‘policy mix’) affects the level of demand in the economy. This block completes the demand side of the macroeconomics part of the course. At this stage, we are still making the strong assumption that the price level is fixed, an assumption that will be relaxed subsequent chapters. Because the price level is fixed there is no distinction between nominal and real values, so that all the variables in the analysis of this chapter can be thought of as real. Historically the model was called the IS-LM model, where the LM schedule depicted a monetary policy that targets money supply. This has now been updated to reflect the fact that central banks target the interest rate. The textbook has an appendix on the IS-LM model but you are not required to study it and will not be examined in it. Note, some sources might call the MP curve the LM, even though its interpretation and meaning is not the same as the original LM of the IS-LM model. The IS-MP model has its limitations. One criticism is that it assumes fixed prices. Another is the fact that it is a static model, while interest rates are meaningless unless time is a factor. Nonetheless, it is a useful model for clarifying several fundamental mechanisms and is often still used by policy-makers (see, for example, a defence for teaching it by the Nobel Prize laureate Paul Krugman: http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/islm. html). Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • describe different forms of monetary policy • derive the IS curve • explain the MP curve • find equilibrium in both the output and money markets • link shifts in the curves to fiscal and monetary policy respectively • discuss the impact of fiscal policy • discuss the impact of a shock to money demand • use graphs to describe the effect of the mix of monetary and fiscal policy. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 23 (except 23.6 and the appendix). 169 EC1002 Introduction to economics Synopsis of this block This chapter introduces the IS-MP model and uses this to give insights into how monetary and fiscal policy work and how the government and the central bank manage demand in the economy. A derivation of the IS-MP model is included in this block (although this is not covered in the textbook). The IS curve shows all the combinations of interest rates and output at which the goods market (Y = C + I + G) is in equilibrium, and the MP curve shows the combinations of interest rate and income that imply a particular level of money demand (which the central bank supplies in order to ensure the money market is in equilibrium). Monetary policy ► BVFD: read section 23.1. A key distinction is made here between rules and discretion and focuses on monetary policy as a relationship between the state of the economy and the interest rate chosen by the central bank. The IS-MP model ► BVFD: read section 23.2 and case 23.1. To derive the IS curve, we focus on the investment component of aggregate income and start with the investment demand schedule which shows how a decrease in interest rates leads to an increase in investment. For example, in the graph below, a fall in interest rates from 10% to 8% leads to an increase in investment from 150 to 200. r 10% 8% I 150 200 I Δ = 50 Figure 15.1: Investment schedule. Since investment is part of autonomous demand, the increase in investment of 50 leads to an increase in autonomous demand of 50. As such, the increase in demand shifts up the AD curve. If we assume that the multiplier is equal to 5, this would lead to an increase in output from 1,500 to 1,750. 170 Block 15: Monetary and fiscal policy AD AD (r = 8%) B Δ = 50 AD (r = 10%) A 350 300 45° 1500 1750 Y r 10% A B 8% IS 1500 1750 Y Figure Deriving the curve. A: at 15.2: an interest rate ofIS10% the goods market is in equilibrium at 1500 B: atAanshows interest of 8% theingoods market is in equilibrium 1750 Point anrate equilibrium the goods market where theatinterest The IS curve gives you all the combinations of interest rate and income rate is 10% and output is 1,500. Point B shows an equilibrium where the where rate the goods is in equilibrium interest is 8% market and output is 1,750. Mapping points A and B onto a graph of interest rates against output gives us the IS curve. The IS curve shows all the combinations of interest rate and income where the goods market is in equilibrium. Deriving the IS curve Recall the basic macroeconomic equation for a closed economy with no government. In this case Y = C + I. As saving S = Y − C this implies that S = I. For this reason the curve derived from this argument is called the IS curve (I investment, S saving). Up to now the consumption function has been C = A + cY . Now suppose that consumption depends on income Y and the interest rate r for reasons discussed in Block 14, so the consumption function becomes C = A0 − ar + cY where a > 0; consumption is lower when the interest rate is higher. Investment also depends on r so I = I0 − br, so Y = A0 − ar + cY + I0 − br which implies that (1 − c) Y + (a + b)r = A0 + I0 . As c < 1, so 1 − c > 0, and as a > 0 and b > 0, so a + b > 0. If you draw this line in a diagram with r on the vertical axis and Y on the horizontal axis you get a downward sloping straight line. Now continue to assume that the economy is closed and introduce a government with expenditure G and tax revenue T so Consumption = A0 − ar + c(Y − T) Investment= I0 − br 171 EC1002 Introduction to economics Equilibrium requires that at their planned levels Y = C + I + G = A0 − ar + c(Y − T) + I0 − br + G so (1 – c)Y + (a + b)r = A0 + I0 + G − cT. As c < 1, a >0 and b >0, given the values of G and T this is a downward sloping straight line in a graph with Y on the horizontal axis and r on the vertical axis. Again, this line is called the IS curve. Movements along the line are caused by changes in the interest rate. An expansionary fiscal policy, that is, an increase in G or a decrease in T, shifts the IS curve upwards. If consumers become more optimistic so A0 increases, or investors become more optimistic so I0 increases, this also shifts the IS curve upwards. Activity SG15.1 Given the following information, provide a graphical derivation of the IS curve: The multiplier is equal to three. When interest rates are equal to 5%, autonomous demand is 200. When the interest rate rises to 8%, investment falls from 100 to 80. The MP curve The MPLM curve reflects the central bank’s monetary policy – that is, its desired interest rate at each income level, money supply being passively adjusted to maintain money market equilibrium. Movements along the MP schedule reflect changes to implement current monetary policy. If income rises, approaching potential output, then central bank raises the interest rate. • A shift in MP curve corresponds to a change in monetary policy. A looser monetary policy would imply a lower level of interest at any particular income level, so the MP curve would shift downwards. Irrespective of the shift, the central bank is passively adjusting money supply to equal the new level of money demand. • The slope of the MP reflects how aggressively the central bank raises interest rates as output and income increase. A shallow slope would mean interest rates are not adjusted much when income changes. • A vertical MP schedule describes the extreme monetary policy stance of aiming to stabilising output completely, no matter what! Read pg. 463 for a discussion of why targeting a particular output level is unrealistic. What would a horizontal MP reflect? Read concept 23.1 for more details. ► BVFD: read section 23.3 to 23.5 and concept 23.1. Complete activity 23.1. Combining the IS and MP together gives Figure 15.3 (or figure 23.2 in the textbook). Point X where they meet gives the interest rate- output pair that simultaneously brings about equilibrium in the goods market and the money market, given the central bank’s policy preferences. 172 Block 15: Monetary and fiscal policy r MP X r* IS Y* Y Figure 15.3: IS-MP The IS-MP in action The framework allows us to examine the effects of fiscal policy (BVFD figure 23.4), shocks to money demand, and to explore the effects of policy mix (BVFD figure 23.5). As illustrated in BVFD figure 23.4, an increase in government spending, G, shifts out the IS curve, as aggregate demand rises for any given interest rate. For a given MP this leads to an increase in output and an increase in interest rates. However, this increase in interest rates will lead to a fall in private spending – as consumption and investment are crowded out. This means that the overall increase in output is less than it otherwise would have been. To a certain extent, the increase in government spending has replaced private spending that would otherwise have taken place. If the central bank also decides to loosen monetary policy, then it is possible to keep the interest rate unchanged (in which case there is no crowding out of consumption and investment) and the full change in income takes place (as determined by the government spending multiplier). Not all economists are convinced by the notion that increases in government spending crowd out private investment. One counter argument is that when confidence is very low, say in a deep recession, government spending may actually crowd in private spending by boosting confidence in the future performance of the economy. What about a shock to money demand? It has no impact on our IS-MP framework at all, since any change in money demand is immediately accommodated in order to implement the monetary policy reflected by the MP curve. Activity SG15.2 Using the IS-MP framework, analyse i) a fiscal contraction, and ii) a tightening of the central bank’s monetary policy so that a higher interest rate is set at each level of income. 173 EC1002 Introduction to economics Activity SG15.3 Describe the policy mix you would adopt in the following situations, assuming you are in a position of power over both fiscal and monetary policy, and provide an explanation of the reasoning behind your decision: a. A very deep recession. b. There is a need to build a solid foundation for long-term growth, but there is currently a temporary bubble in the economy. c. The country is heavily engaged in a war which is being fought outside of the country. ► BVFD: read section 20.7, the summary and work through the review questions. Overview This block introduces the IS-MP model and explains the shape and meaning of each curve. Fiscal policy shifts the MP curve while monetary policy shifts the LM curve. A loosening of fiscal policy leads to a higher interest rate and higher output, with government spending a large part of total spending. An expansionary monetary policy leads to lower interest rates and higher output, with private consumption spending and investment making up a large part of total spending. These two policies can be used to support each other or balance each other out. Often, fiscal policy will be heavily influenced by political concerns, while in many countries the central bank makes decisions on monetary policy independent from political influences. This model provides a simple way of depicting the effects of each policy, as well as policy mixes. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. A movement along the IS curve represents: a. A change in fiscal policy. b. A change in monetary policy. c. A decline in investment spending, but an increase in savings. d. A decline in savings, but an increase in investment spending. 2. Suppose the government cuts taxes but does not change expenditure or monetary policy. Assume that the central bank is setting the interest rate. Which of the following statement is correct? a. The IS curve shifts downwards. b. The MP curve shifts downwards. c. Income increases but the interest rate remains the sane. d. Both income and the interest rate increase. 174 Block 15: Monetary and fiscal policy 3. Which of the following causes a shift in the MP curve? a. The government decides to lower taxes. b. People start spending more, so the marginal propensity to consume increases. c. The government imposes a ban on imports from another country. d. The central bank decides to loosen monetary policy. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Central banks can offset temporary demand shocks but in doing so they will face a trade-off between stabilising output or inflation. 2. Central banks are unlikely to be able to perfectly stabilise output. 3. Crowding out prevents any additional money spent by the government to increase the output of a country. Long response question 1. a. The IS–MP diagram has income on the horizontal axis and the interest rate on the vertical axis. What is the MP schedule in this diagram? Why is it upward sloping? b. What is the IS schedule in the IS–MP diagram? Why is it downward sloping? Assume the economy is closed and explain your answer mathematically. c. Use the IS–MP model to show how fiscal and monetary policy can be used to increase output without changing the interest rate. d. What are the limitations of the IS–MP model that policymakers should be aware of? 175 EC1002 Introduction to economics Notes 176 Block 16: Aggregate demand and aggregate supply Block 16: Aggregate demand and aggregate supply Introduction Blocks 13–15 discuss economic ideas that have their origins in the 1930s, particularly in Keynes’ 1937 book, ‘The general theory of employment, interest and money’ (always called the general theory) and Hicks’ 1937 paper which introduced the IS-LM model. The 1930’s were a time of high unemployment and low or even negative inflation (deflation). In this situation it was natural to ignore inflation and focus on a situation in which the economy has the potential to produce more than it was producing so the level of output is determined by aggregate demand. Both Hicks (1904–1989) and Keynes (1883–1946) were very concerned about of the possibility of inflation and, wrote about this elsewhere, but in the situation of the 1930’s it was not a major issue. Following the 2007–08 financial crisis many countries again found themselves in a low inflation and high unemployment situation and some economists have returned to the ideas of Keynes and other economists of the 1930s. After World War II (1939–45) Keynesian economics was largely the framework for economic policy in many countries, including the USA and UK, until the 1970’s. During this period both inflation and unemployment were low. Prompted by a range of factors, including policy responses to the Covid-19 pandemic and disruptions to the supply of energy, in 2022 we find ourselves in a new era of inflation. Central banks have been raising interest rates with caution to contain inflation, while also trying not to slow or reverse economic recovery from the pandemic. Therefore, the assumption of fixed prices, appropriate for the past three decades, is no longer appropriate. We therefore should explore what drives prices and examine the macroeconomy and macroeconomic policies in the context of flexible prices. This block examines aggregate supply and aggregate demand, looking at both short- and long-run adjustment. Blocks 17 and 18 explore inflation and unemployment in a closed economy. Macroeconomics as discussed in BVFD works with the assumption that in the long-term wages and prices move to their equilibrium level at which all markets clear. However, in the short term prices are ‘sticky’ so do not change easily, the movement to the market clearing equilibrium may be slow, and there is scope for government intervention. We now turn to the the relationship between short-run and long-run equilibrium in this setting. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • describe inflation targets for monetary policy • explain and graph the rr schedule • describe how inflation affects aggregate demand • define aggregate demand and graph the AD schedule • define aggregate supply in the classical model 177 EC1002 Introduction to economics • analyse the equilibrium inflation rate • describe complete crowding out in the classical model • recognise why wage adjustment may be slow • analyse short-run aggregate supply • discuss the effects of short-run and permanent demand and supply shocks • describe how monetary policy reacts to demand and supply shocks • recognise flexible inflation targets • explain the Taylor rule. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 24. Synopsis of this block In a context of flexible prices and wages, this block firstly defines aggregate demand and the AD curve, and then aggregate supply and the AS curve. The AD-AS model can be used to show how output and the rate of change of the price level are determined. This block examines how the economy adjusts to different kinds of demand and supply shocks and how the government (through the central bank) can respond to bring output back to the potential level of output and keep inflation on target. The different perspectives of the classical and Keynesian school on the flexibility of prices is a key element of this chapter. One major reason why prices are not flexible is that wages are sticky downwards. The advantages and limitations of government intervention are discussed, as well as various approaches to monetary policy, including flexible inflation targeting and the Taylor rule. Aggregate demand ► BVFD: read section 24.1. In the early blocks on macroeconomics, there was an underlying assumption that the price level is fixed, and aggregate demand was simply defined as planned or desired spending. From this block onwards, we leave this assumption behind, and can now represent aggregate demand at various price levels. This is summarised by the (dynamic) AD curve, which shows the relationship between output and inflation. Section 24.1 explains why the AD curve is downward sloping in a model with inflation on the vertical axis. Interest rates and central bank inflation targeting are the links between inflation and output. When inflation is high, inflation-targeting central banks raise interest rates and this reduces those components of aggregate demand, such as investment, which are sensitive to interest rates. Consumption is also affected by interest rates because people often buy durable goods (such as washing machines) on credit. In the UK, changes in the interest rate immediately affect the cost of many mortgages (loans for buying housing). This also decreases consumption. . It is important to be clear that the implementation of a given monetary policy moves the economy along a given rr schedule while a general tightening or loosening of monetary policy shifts the whole rr schedule upwards or downwards. ► BVFD: read concept 24.1. 178 Block 16: Aggregate demand and aggregate supply The approach adopted in BVFD for explaining the AD schedule is clarified further in concept 24.1. This shows how input/output, interest rates and inflation are all interrelated. You may find it easier to see what is happening in concept box 24.1 if you work with an algebraic model of aggregate demand. Using notation π inflation, Y output and r real interest rate the central bank sets its real interest rates according to its policy rule r = gπ where g > 0 because high inflation results in a high interest rate. This is called the ii schedule in concept box 24.1. Monetary policy becomes tighter if g becomes larger, because the bank sets a higher real interest rate at each level of inflation. The IS schedule is downward sloping and has an equation of the form r = ℎ − kY where k > 0 because at a higher interest rate there is less consumption and investment so less output. Thus gπ = h – kY so π = (h – Y) / g is the equation of the aggregate demand schedule giving the inflation rate π as a function of the level of output Y. As g >0 and k > 0 the aggregate demand schedule is downward sloping. Aggregate supply ► BVFD: read section 24.2 and case study 24.1. We now move away from the Keynesian model, with rigid wages and prices in which output is entirely demand determined, and include a supply-side in the model of output determination. Aggregate supply describes the relationship between the output that businesses willingly produce and the rate of inflation, with other factors held constant. Initially, the textbook introduces the vertical aggregate supply curve. This is often known as the long-run aggregate supply curve, as it is based on the assumption that prices and wages are completely flexible and the real wage adjusts to clear the labour market. While almost all economists would agree that prices and wages are flexible in the long run, the classical school assumed they were always flexible. For example, suppose inflation increased; if nominal wage growth did not change then real wages would fall. But in the classical model, nominal wage growth would match the new, higher, rate of inflation so that real wages would be unaffected and there would be no forces acting to change aggregate output. The vertical aggregate supply curve shows that in the long-run there is no relationship between inflation and the level of output (similar arguments make the level of output independent of the price level, but in this chapter, as explained above, we relate output to inflation rather than to the price level). The level of output is the full employment equilibrium level and, in the long run, can co-exist with inflation at any level. Resources are fully employed since price and wage flexibility ensures that all markets, including the labour market, are in equilibrium, with no shortages or surpluses. Optional: For some interesting examples of money illusion and a fuller discussion, see: Shafir, Diamond and Tversky (1997) ‘Money illusion’, available at: http://qje.oxfordjournals.org/content/112/2/341.short 179 EC1002 Introduction to economics Equilibrium inflation ► BVFD: read section 24.3 to 24.5. Now we can finally put together the pieces of the full model – aggregate demand and aggregate supply – to show both the level of output and the inflation rate. Where the two curves intersect, there is equilibrium in the goods market, the money market and also the labour market. The position of the vertical AS curve reflects potential output. The position of the AD curve reflects the government’s monetary policy and the impact of interest rates on the goods market. In the long run, aggregate supply is vertical at the level of potential output determined by the economy’s available inputs and its technology (broadly defined). All prices, inputs and outputs increase at the same rate so nothing real changes. For example both money wages (nominal wages) and prices change at the same rate so the real wage, which affects both the supply of and demand for labour, is unchanged. The equilibrium inflation rate coincides with the inflation target. Figure 24.5 shows why it can be useful to understand the AD curve from the perspective of interest rates. Then, we can see how the government can respond actively to a shift in aggregate supply. In this case, the government responds to an increase in aggregate supply by reducing interest rates, as this leads to an increase in aggregate demand such that inflation is maintained at the target rate. Activity SG16.1 Beginning at point C in Figure 24.6, where would the economy end up if there was an adverse supply shock shifting the AS curve from AS1 to AS0 and the central bank did not react? Activity SG16.2 Select the appropriate response below with regards to the following two statements: i. Central banks can offset temporary demand shocks but in doing so they will face a trade-off between stabilising output or inflation. ii. Central banks can offset temporary supply shocks without facing any trade-off between stabilising output or inflation. a. i is true and ii is false. b. ii is true and i is false. c. i and ii are both true. d. i and ii are both false. In the classical model, fiscal expansion cannot increase output. To stop inflation rising above the target, an increase in government spending will have to be countered by a rise in real interest rates to restore aggregate demand to the level of potential output. This means that higher government spending simply crowds out an equal amount of private spending, leaving demand and output unchanged. This sub-section on demand shocks shows why it was so revolutionary for John Maynard Keynes to suggest, in the Great Depression of the 1930s, that the solution was to increase government spending. One key contribution of Keynesian economics was that, at least in the short run, prices and wages may be sticky, such that output is not at the full employment equilibrium level. In such a situation, increasing the level of aggregate demand by increasing 180 Block 16: Aggregate demand and aggregate supply government spending can increase output without bringing the inflation rate above target. Monetarism, whose most famous and influential exponent was Milton Friedman of the University of Chicago, became popular in the 1970s and 1980s and proposes that an increase in the money supply will lead to an increase in prices (or, in terms of the framework of this chapter, faster growth of the nominal money supply leads to higher inflation) but would not affect real variables in the long run. This is based on the ‘quantity theory of money’, which is discussed further in the next chapter in chapter 25.1 (but is not part of the course and thus not examinable). Seen very broadly, the perspectives of the classical school and the Keynesian school can be synthesised by taking a long-run/short-run approach. In the long run, the AS curve is vertical, as proposed by the classical school. The following section shows why, as proposed by the Keynesian school, this does not hold in the short run, where prices and wages are ‘sticky’ (i.e. do not move flexibly, especially downwards). Wage rigidity ► BVFD: read section 24.4. This section discusses wage rigidity. It summarises why prices are sticky (especially downwards), since wages, the largest component of firms’ costs, adjust slowly to changes in demand. Prices may also be sticky for other reasons, such as the fact that it is costly for firms to set, implement and advertise new prices – this may lead to a reluctance to increase prices, even in situations where a price increase would be expected, for example due to a major increase in costs or demand. Short-run aggregate supply ► BVFD: read section 24.5. Why do SAS curves slope upwards? The discussion below should help you understand the explanation in the textbook. In the short run, some prices cannot adjust or can only do so partially. To derive an upward sloping short-run supply curve, this chapter assumes a very specific type of labour market rigidity, namely that, in the shortrun, firms are stuck with a given rate of growth (note: not level) of nominal wages inherited from previous wage negotiations. Prices change more easily than wages. Both suppliers and demanders of labour will have negotiated the rate of growth of money wages on the basis of their inflation expectations (i.e. they will have implicitly been negotiating over real wages). If the rate of change of nominal wages is fixed by wage agreements but inflation deviates from the rate assumed by the parties to such agreements then the real wages will differ from those implicitly agreed by the negotiating parties. Now suppose that for given expectations about the growth of money wages and prices, the rate of inflation is higher than expected. Firms get higher prices for their product and real wages are lower than expected because prices are rising faster than was expected when nominal wage growth was negotiated. So production becomes more profitable and firms increase output. Similarly, if inflation is lower than expected the prices at which firms sell their output is lower than they were counting on and real wages are greater than expected. Output falls, unemployment increases. 181 EC1002 Introduction to economics After a period of time, if inflation deviates from its expectations and thus the workers and firms are not receiving and paying the real wages they negotiated, they will go back and renegotiate how fast nominal wages grow and this in turn will shift the whole short run AS schedule, that schedule having been drawn for a given rate of change of money wages. The short-run aggregate supply curves in Figure 24.8 can be written: Y = Y* + α(π – πe) where α is a positive constant and πe is expected inflation. As explained, each supply given is based on inherited agreements on the growth of money wages. Shifts in the SAS curve: Each SAS curve reflects a given rate of inherited nominal wage growth (and more generally, given input prices). When inherited nominal wage growth is lower, firms will not increase prices as quickly, and the SAS curve will be lower. Changes in input prices and changes in productivity also both lead to shifts in the SAS curve. Another interpretation of sticky wages and the response to unanticipated inflation is discussed by Keynes in the general theory. This is the situation in which production takes time. When the decisions are made about how many people to employ the money wage and the nominal interest rate are known. However, the price at which the output will be sold and the rate of inflation are uncertain so the real wage and real interest rate are not known for sure. People have to act on the basis of their beliefs; they may or may not be correct about the average, but there will inevitably be surprises. The theory discussed here was developed before the internet was even imagined. Now some wages are determined by algorithms and vary minute by minute. The model discussed in BVFD simplifies by treating all labour as being the same. More elaborate models can take into account the fact that wages are very flexible in some but not all parts of the economy. Adjustment to demand shocks ► BVFD: read section 24.6 and complete activity 24.1. Section 24.6 shows how, following a demand shock, the gradual adjustment of wage growth eventually brings output to the full employment level (potential output) and demonstrates how short-run aggregate supply curves and the vertical (long-run) aggregate supply curve fit together. Below is a description of both positive and negative demand shocks. Starting at point A, a positive demand shock shifts the AD curve from AD0 to AD1, leading to a higher output level and a higher rate of inflation at point B. In time, facing higher inflation than was built into wage negotiations and thus experiencing a falling real wage, workers will negotiate higher wage growth and the SAS curve will start shifting upwards to the left. The higher wage growth will be partly passed on through higher prices, and output will fall until it is back to the long-run equilibrium level Y*. The adjustment process for a negative demand shock (described more fully in section 24.6) is similar just in the opposite direction, with the AD curve shifting left from AD0 to AD2, moving the economy into recession at a lower rate of inflation. At point D, there is involuntary unemployment. This will put downward pressure on future wage negotiations, resulting in lower wage growth and a shift in the SAS curve, eventually to point E. 182 Block 16: Aggregate demand and aggregate supply AS SAS1 Inflation π1 π0 π2 SAS0 C ② A D ② ① SAS2 B ① E AD1 AD0 AD2 Y* Output, income (GDP) Figure 16.1 Demand shocks. ► BVFD: read section 24.7. While section 24.6 describes the adjustment mechanism of how the economy is brought back to the potential output level via market forces (notably the change in re-negotiated wage growth), the government can also act discretionally to influence the level of aggregate demand. Section 24.7 outlines how the central bank can react to shocks using monetary policy, and the advantages and limitations involved. One important point to realise is that the downward sloping AD curve used in this chapter implicitly assumes that the central bank is making a compromise between stabilising inflation and output in the face of temporary supply shocks. If the central banks cared only about the inflation target, the rr curve drawn and explained in section 21.1 would be vertical at the target inflation rate – the bank would immediately offset any change in actual inflation from target by varying the interest rate. In this case the AD curve would be horizontal – only one inflation rate would be possible, the target rate, and in the face of temporary supply shocks real interest rates and output would have to vary by whatever is required to maintain the inflation target. For example, an adverse supply shock which would normally increase inflation in the short run would have to be immediately countered by an increase in the interest rate sufficient to hold inflation constant. Output would fall correspondingly. Activity SG16.3 Identify the following shocks (demand or supply, permanent or temporary, positive or negative) and use AD-AS curves to demonstrate their short-run and long-run effects on output and inflation. Clarify the appropriate monetary policy response and its effects on output and inflation. i. A technological breakthrough significantly enhances productivity ii. A major trading partner suffers a deep recession iii. A country realises that its stock of minerals is significantly lower than what it had previously estimated iv. The price of a key input into production rises for some time. ► BVFD: read section 24.8, concept 24.2 and maths 24.1. 183 EC1002 Introduction to economics Activity SG16.4 Search online to find some predictions or analysis relating to the expected (or announced) actions of a major central bank (e.g. the Bank of England, US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank). How well do they fit with the theory described in these sections (flexible inflation targeting and the Taylor rule)? ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. Overview This chapter introduces a model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply, showing the relationships between output and inflation. The rr schedule is introduced first to help explain the AD curve. The rr schedule shows, under a policy of inflation targeting, how the central bank sets high interest rates when inflation is high and low interest rates when inflation is low. The rr schedule shifts left (right) when monetary policy is loosened (tightened) – this means at each inflation rate, real interest rates are higher (lower). On the assumption that the central bank is taking this approach, the AD curve shows how higher inflation reduces aggregate demand by inducing monetary policy to raise real interest rates. The classical model of macroeconomics assumes full flexibility of wages and prices and no money illusion. In the classical model, the economy is always at full employment equilibrium. This is represented by a vertical aggregate supply schedule at the level of potential output. Equilibrium inflation occurs at the intersection of the aggregate demand and aggregate supply schedules. Monetary policy is set to make the equilibrium inflation rate coincide with the inflation target. In the classical model, fiscal expansion cannot raise output, but will simply lead to a crowding out of an equal amount of private spending. In the real world, prices and wages do not adjust instantaneously. In particular, wages are thought to be sticky downwards. This is a feature of the Keynesian model of macroeconomics. The Keynesian model is a good guide to short-run behaviour whilst the classical model describes the long run. The vertical aggregate supply curve is thus called the longrun aggregate supply curve. Short-run aggregate supply curves slope upwards. They show firms’ desired output given the inherited growth of nominal wages. Output is responsive to inflation in the short-run because nominal wages are already determined and people’s expectations regarding inflation do not always prove correct. A re-negotiation of the rate of wage growth causes a shift in the short-run aggregate supply curve. Permanent supply shocks alter potential output. Regardless of the policy adopted, their output effects cannot be escaped indefinitely. Temporary supply shocks merely shift the short-run supply curve for a period. These force central banks to make a decision on the trade-off between output stability and inflation stability. Demand shocks however, could be completely offset by monetary policy, if the effects were instant. Flexible inflation targeting implies the central bank need not immediately hit its inflation target, allowing some scope for temporary action to cushion output fluctuations. A Taylor rule views interest rate decisions as responding to both deviations of output from target and deviations of inflation from target. Many central banks appear to follow a Taylor ruletype policy. 184 Block 16: Aggregate demand and aggregate supply Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. In the classical model, the economy is in long-run equilibrium where the equilibrium inflation rate is equal to the target inflation rate. The economy suffers an adverse supply shock (such as a permanent increase in the price of raw materials). In the new equilibrium: a. Equilibrium inflation is below the target inflation rate and the government needs to loosen monetary policy to achieve its target. b. Equilibrium inflation is above the target inflation rate and the government needs to tighten monetary policy to achieve its target. c. Equilibrium inflation is below the target inflation rate and the government needs to tighten monetary policy to achieve its target. d. Equilibrium inflation is above the target inflation rate and the government needs to loosen monetary policy to achieve its target. 2. If prices and wages are completely flexible which of the following statements about the classical model of aggregate supply is not correct? a. Aggregate supply is a vertical line in the diagram with output on the horizontal axis and inflation on the vertical axis. b. Aggregate supply is completely unaffected by inflation. c. If there is a shock which increases aggregate supply and no change in monetary policy the inflation rate and output both increase. d. If there is a shock which increases aggregate supply monetary policy can be used to get the economy back to the original inflation rate. 3. According to the sticky-wage model of economic fluctuations, when inflation is lower than expected, workers get a (i) _______ real wage than expected and (ii) _______ workers are hired than expected (indicate which words go on the blanks labelled (i) and (ii)). a. (i) lower, (ii) more b. (i) lower, (ii) fewer c. (i) higher, (ii) more d. (i) higher, (ii) fewer. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Suppose the central bank of an economy controls the money supply. With a permanent positive supply shock it is possible for the economy to have lower inflation and lower real interest rates without the central bank changing its monetary policy. 2. After an increase in oil prices, if the central bank wishes to maintain the pre-shock inflation target monetary policy will have to be tightened. 185 EC1002 Introduction to economics 3. A temporary increase in raw materials prices does not warrant an intervention from the central bank, as the shock will not cause any change in the long-run equilibrium output of a country. Long response questions: 1. a. The aggregate demand and aggregate supply diagram has output on the horizontal axis and inflation on the vertical axis. Explain the derivation of the aggregate demand schedule from the IS schedule and monetary policy. Why is it downward sloping? Explain your answer mathematically. b. What causes movements along the aggregate demand schedule? What happens to the aggregate demand schedule if government expenditure increases and tax revenue does not change? What happens to the aggregate demand schedule if the target inflation rate is increased? c. What is the shape of the aggregate supply curve if prices and wages are completely flexible. What determines potential output? d. Suppose that an economy starts at a point where aggregate demand and short and long aggregate supply are all equal. The central bank then tightens monetary policy in order to reduce the rate of inflation. Use a diagram to discuss what happens to aggregate demand and supply in the short and long run. 186 Block 17: Inflation Block 17: Inflation Introduction In Block 16, we analysed how changes in aggregate demand and aggregate supply affect output and inflation. Inflation, economic growth (i.e. growth in output) and unemployment are the three key macroeconomic indicators you will most likely have heard discussed in the media. In this block, we focus on inflation, which is defined as a rise in the general level of prices. This block examines the causes of inflation, its implications, as well as policies to address it. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • discuss nominal and real interest rates and inflation • assess when budget deficits cause money growth • explain the Philips curve • analyse inflation expectations • evaluate the costs of inflation • discuss central bank independence and inflation control • analyse how central banks set interest rates. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 25 (except 25.1). Synopsis of this block The central topic covered in this block is the Phillips curve. The shortrun Phillips curve demonstrates a trade-off between inflation and unemployment in response to demand shocks. The long-run Phillips curve is vertical at equilibrium unemployment. People’s expectations regarding inflation are central to the analysis of inflation and the difference between the short and long-run Phillips curves. The costs of inflation include shoeleather costs and menu costs, as well as undesirable redistribution in the case of unexpected inflation. Deflation is seen as an even greater problem than inflation. Central bank operational independence has been a key institutional change that has made inflation targets more credible and facilitated a long period of low inflation in many advanced economies. BVFD 25.1 describes the quantity theory of money. This is part of the traditional theory of monetary economics and is not part of this course. Money and inflation ► Read BVFD section 25.2. This section describes the Fisher equation1: Real interest rate = [nominal interest rate] – [inflation rate]. as well as the effect of nominal money growth on nominal interest rates and the demand for real money. The section also distinguishes between the Fisher equation, above, and the Fisher hypothesis which states that real interest rates don’t vary all that much as nominal interest rates and inflation tend to move in tandem. Note that, strictly speaking, this equation is only an approximation, but one that is reasonably accurate as long as the rates are not too large. The exact formula is that (1+i)=(1+r)/ (1+π). Suppose the nominal interest rate is 8% and inflation is 5%. This makes the real rate 2.857%. Using the Fisher equation it is 3%. 1 187 EC1002 Introduction to economics If nominal money growth leads to a fall in demand for real money, P must rise faster than M so that real money supply (M/P) falls in line with the fall in demand for real money. ► BVFD: read section 25.3. If governments have been running persistent deficits and the ratio of accumulated debt to GDP is high they will find it difficult to continue to finance deficits by borrowing; potential lenders fear they will not be repaid. Governments need to tighten fiscal policy in such circumstances, but they might instead be tempted to finance ongoing deficits by printing money (or increasing the money supply in some equivalent manner). In an extreme situation this results in hyperinflation. The Phillips curve and inflation expectations ► BVFD: read section 25.4. In 1958 Willliam Phillips published a paper establishing a statistical relationship between unemployment and output in the UK, which became known as the Phillips curve. This suggested that there was a trade-off. If inflation was high unemployment was relatively low; if inflation was low unemployment was high. However, in the late 1960s and 1970s both inflation and unemployment were much higher than they had been in the 1950s, and early 1960s and people came to expect inflation. The Phillips curve relationship had broken down. The modern interpretation of the short- and long-run Phillips curve relates closely to the concept of aggregate supply, which was introduced Block 16. In the model short-term aggregate supply is upward sloping in a graph with output on the horizontal axis and inflation on the vertical axis. In the long run aggregate supply is a vertical straight line, there is no impact of inflation on long-run aggregate supply. In the short run the the nominal (money) wage rate is assumed to be fixed. It depends on how much inflation was expected at the time the wage was fixed. If inflation is higher than expected then the real wage (money wage/price of output) is lower than expected, and employment and output are relatively high. Block 16 tells the story in terms of output. Block 17 tells the story in terms of employment, but it is the same story. Unexpected inflation results in higher employment and output in the short run but expected inflation has no effect. Up to this point in the chapter, the emphasis has been on monetary and fiscal relationships. Section 25.4 relates these more explicitly to the real economy (via output and unemployment) and begins to analyse the crucial role of expectations in macroeconomics. The Phillips curve,2 which depicts the relationship between unemployment and inflation, is introduced. Just as there was for aggregate supply, there is both a long-run Phillips curve and a short-run Phillips curve. The short-run curve slopes downwards, depicting a trade-off between unemployment and inflation. This can be explained in a simple and intuitive way as follows. In the short run, when inflation increases unemployment decreases. For example, inflation is usually demand-pull inflation, this occurs when aggregate demand increases. The quantity supplied by firms needs to increase to meet the increase in aggregate demand, and to increase quantity supplied, firms must hire more workers, hence unemployment falls. Higher prices make firms supply more output and demand more workers. Alternatively, when unemployment rises, inflation falls. This could be because as 188 Named after New Zealand-born economist A.W. Phillips, who spent much of his academic career at the London School of Economics. Apart from using statistical methods to investigate the relationship between unemployment and inflation, the subject of this section, Phillips (who initially trained as an engineer) was also famous for building an analogue hydraulic computer which could be used for modelling the macro economy. Several copies of this machine still exist. 2 Block 17: Inflation unemployment rises, people can no longer afford to buy as many goods and services. Thus firms must lower their prices to attract customers and inflation falls. In its original form (naïve form, some would say) such a relationship could be written as: π = a0 – a1u where a0 > 0 and a1 > 0 This trade-off at first seemed to offer a powerful lever to policy makers seeking to an acceptable compromise in attaining two of the most important but seemingly conflicting macroeconomic objectives (low unemployment and low inflation). However, this trade-off was soon revealed to be illusory over the longer term; the long-run Phillips curve is vertical – equilibrium unemployment is independent of inflation. Demand shocks will move the economy along the short-run Phillips curve – permitting the economy to temporarily diverge from equilibrium levels. Thus an inflation rate that is different from people’s expectations leads to a movement along the short-run Phillips curve. The height of the short-run Phillips curve is affected by people’s expectations about future inflation. A change in expectations leads to a shift in the short-run Phillips curve. Temporary supply shocks also affect the height of the short-run Phillips curve (causing it to shift upwards or downwards), while permanent supply shocks affect the position of the long-run curve. ► BVFD: read Maths 25.1. Inflation depends on inflation expectations and the gap between the actual and equilibrium unemployment rates. Inflation expectations also depend on this gap. Therefore, inflation is affected by deviations of unemployment from the equilibrium rate through two channels – directly, and also through the impact on expectations. Second, Equation (1) (representing the short-run Phillips curve) shows that the gap between inflation and inflation expectations is proportionate to the difference between actual and equilibrium unemployment. Equation (4) shows that the gap between actual and potential output is also proportional to the difference between actual and equilibrium unemployment. Putting these together lets us find the short-run aggregate supply curve (equation 5) which shows the relationship between the gap between actual and potential output and the gap between inflation and inflation expectations. One of the central points in this section is the correspondence between the Phillips curve and the aggregate supply curve (see Figure 22.6 and associated discussion). We can see this mathematically by recalling from the previous block that aggregate supply can be written: Y = Y* + α(π – πe) which we can rewrite as: 1 π = πe + α (Y – Y e) Now we want to go from output, Y, to unemployment, U. We can do this via a version of Okun’s Law, named after the American economist Arthur Melvin Okun who, in the 1960s, investigated the relationship between changes in the unemployment rate and the growth rate of output in the USA. If we argue that deviation of output from its potential level is inversely related to the deviation of unemployment from its equilibrium rate (following the notation used in Maths 25.1): 189 EC1002 Introduction to economics Y – Ye = –h(U – Ue) where h > 0. Then substituting into the equation for inflation above we have: π = πe – b(U – Ue) Where b = h > 0 α This version of the Phillips curve is sometimes called the expectationsaugmented Phillips curve, in comparison to the original or naïve Phillips curve shown above. Note that this equation3 is the same as the first equation in Maths 25.1, to which we return shortly. The argument in Maths 25.1 begins with the short-run Phillips curve and shows this to be equivalent to the short-run supply curve. Here we have done the reverse, starting with the short-run supply curve of the previous chapter and showing that it is equivalent to the short-run Phillips curve. It is easy to see from this equation that when, in the long-run, actual and expected inflation are equal, unemployment is at its natural or equilibrium rate. Note that this argument applies to any level of actual and expected inflation. There is no unique inflation rate corresponding to equilibrium unemployment; equilibrium unemployment requires that expectations about inflation are fulfilled, but this can happen at any level of inflation. When reading news reports on the state of the economy, you may have come across the term ‘NAIRU’, this is an acronym which means the ‘nonaccelerating-inflation rate of unemployment’. This is the unemployment rate consistent with maintaining stable inflation. It is similar to the natural rate of unemployment discussed in this current chapter.4 Understanding the accelerationist hypothesis from this concept lets us understand where the terminology of the NAIRU comes from. When output is at its potential level, the unemployment rate is not zero, even though this state is sometimes referred to as the ‘full employment level of output’. There will be a certain level of unemployment that is not caused by a lack of demand, but rather is caused by the movement of people between jobs (frictional unemployment) or a mismatch in the skills that workers have and the skills demanded by employers (structural unemployment). If unemployment is pushed below its natural rate, or below the NAIRU, inflation will tend to accelerate. To decrease unemployment permanently without generating inflation, governments try to decrease the NAIRU by increasing the efficiency of labour markets and focusing on skills, such as through retraining programmes. From our analysis above, and that in concept 22.2 which you have just read, it is clear that people’s expectations about inflation are crucial. If we rewrite the above equation with time subscripts, t, t = te – b(ut – u*) and assume that people expect this period’s inflation to be the same as last period (adaptive expectations) then we can see that if policy makers keep current inflation above last period’s inflation they can hold unemployment below the natural rate. Would people really be fooled by policy makers simply accelerating inflation; would they not build this into their inflationary expectations? Where this is the case, with so called ‘rational expectations’, the short-run trade-off between unemployment below its equilibrium rate and accelerating inflation would not exist.5 This section contains a lot of detail on how the economy functions – it may be good to read it through several times. Two important concepts from this section are the natural rate of unemployment – which is the 190 Note that this equation can also be written as π = πe – b(u – u*) + v where v is used to indicate a short-run supply shock (longrun supply shocks change equilibrium unemployment, u*). Thus vertical shifts of the short-run Phillips curve can result from changes in inflation expectations and/or from temporary supply shocks, the latter giving rise to cost-push inflation. 3 The natural rate of unemployment can be seen as a more long-term concept, whilst the NAIRU can be interpreted as the unemployment rate consistent with steady inflation in the near term. In full equilibrium, they are the same. 4 The rational expectations hypothesis is particularly associated with the American economist Thomas J. Sargent who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2011 (jointly with Christopher A. Sims). 5 Block 17: Inflation long-run equilibrium level of unemployment (this is not zero – more on this later); and stagflation – which is the situation where inflation and unemployment are both high, as many economies experienced during the 1970s due to high oil prices. The experience of stagflation in this period is what initially led economists to question the validity of the Phillips curve. Activity SG17.1 Based on Figure 25.6, use the LRAS and the long-run Phillips curve, together with the short-run curves, to depict what will happen to output, unemployment and the price level when there is: a. a negative shock to aggregate demand in the context of a credible, constant inflation target b. an expectation that the inflation rate will rise and that the central bank will not be able to contain this c. the productivity of the labour force increases permanently (for example due to changes in the county’s education and training systems) d. a temporary adverse supply shock that is not fully accommodated. The costs of inflation ► BVFD: read section 25.5. This section discusses the costs of inflation, which are very different to what many people think. Economists make a distinction between anticipated and unanticipated inflation. The distinction is useful to think about. However, in practice it is impossible to forecast the rate of inflation. Go to the Bank of England website and search for the ‘Inflation report’. You will see fan charts indicating the uncertainty about the future rate of inflation. Generally the higher the rate of inflation the more uncertain it is, which is an important reason why high inflation is problematic. If inflation could be fully anticipated and all tax rates, nominal interest rates, wage rates etc. fully adjusted then the remaining costs of inflation would be shoe leather costs and menu costs (make sure you understand these concepts). If nominal magnitudes fail to adjust perfectly there are further costs. For example, if tax brackets do not adjust to inflation (‘bracket creep’ or ‘fiscal drag’) taxpayers will find themselves with a higher real tax burden (governments gain). Similarly, if capital gains tax (CGT) is levied on the nominal value of assets people can find themselves paying CGT on assets that have not increased in real value; again taxpayers lose and governments gain. Now suppose that inflation is uncertain and turns out to be higher than expected so prices are higher. Suppose that money wages are fixed. The real wage is then lower so output and employment are higher. Conversely if inflation is lower than expected and the money wage is fixed the real wage is higher and output and employment are lower. It is surprises in inflation that matter here. If nominal interests are indexed to expected inflation then lenders will lose because the real interest rate they receive (the nominal rate minus the rate of inflation) is less than they expected. On the other hand borrowers benefit. Similarly if nominal wages are indexed to expected inflation and actual inflation exceeds expectations workers receive lower real wages than expected. Firms benefit, on the other hand, because their real wage costs are lower than expected. Further costs are incurred if inflation is very volatile 191 EC1002 Introduction to economics or uncertain. Not only does this make planning and writing contracts more difficult but imposes direct utility costs on risk averse individuals or firms. To the extent that higher average inflation is associated with more volatile inflation (there is some evidence for this) this is another argument in favour of maintaining inflation at reasonably low levels. This is not to say that zero inflation would be a sensible target either. Low and stable inflation has benefits as well as costs. An important benefit of having low, rather than zero, inflation arises from noting that zero inflation would provide no margin of error in protecting against deflation. For the perils of deflation read Case 25.1. Controlling inflation ► BVFD: read sections 25.6 and 25.7 and complete activity 25.1. While sections 25.6 and 25.7 are about controlling inflation we have already dealt with the analytics of this in the previous block. The final two sections of the current chapter add some real world institutional context. They describe how credible low inflation targets are used to get inflation under control, and how this has been relatively successful in the past 20 years. Central bank independence has been an important part of this. Nonetheless, deciding where to set interest rates to achieve an inflation target is no easy task. There are continual shocks to the economy of various sizes, and it is not always easy to distinguish permanent and temporary demand and supply shocks, or to know how best to respond to these. Many central banks publish reports after their committee meetings, detailing why they have decided to maintain or to change interest rates.6 Transparency regarding their decision making process also helps to keep inflationary expectations in line. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. Overview The Fisher hypothesis states that higher inflation leads to higher nominal interest rates such that real interest rates do not change greatly. This can be expressed by the Fisher equation: real interest rate = nominal interest rate – inflation. Furthermore, the relationship between inflation and government indebtedness was discussed. Governments with excessive debts may be tempted to print money – though there is some scope for revenue generation through the inflation tax, this approach is very risky and can result in hyperinflations. In most advanced economies, we do not expect a close relationship between deficits and money creation. A very important topic covered in this block is the Phillips curve. The short-run Phillips curve demonstrates a trade-off between inflation and unemployment in response to demand shocks. The long-run Phillips curve is vertical at equilibrium unemployment. Permanent supply shocks shift the long-run Phillips curve left or right, while temporary supply shocks shift the short-run Phillips curve higher or lower. Inflationary expectations also shift the short-run Phillip’s curve, in part because people’s expectations regarding inflation affect negotiated wages and nominal wage growth. Stagflation is the situation where unemployment and inflation are both high. The costs of inflation are different to what many people think – not simply higher prices, but other costs such as shoe-leather costs and menu costs, as well as undesirable redistribution in 192 You can find the Bank of England’s quarterly inflation reports here: www.bankofengland. co.uk/publications/ Pages/inflationreport/ default.aspx 6 Block 17: Inflation the case of unexpected inflation. Although inflation is seen as a problem (although at low and stable levels it has benefits also), deflation is potentially an even greater problem. For this reason, central banks usually have an inflation target slightly above zero, such as the current 2 per cent CPI target rate for the Bank of England. Central bank independence from politics has proven effective in making inflation targets credible and effective in recent years. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. In the case of unanticipated inflation: a. Creditors are hurt by lending but debtors gain by borrowing. b. The elderly (mostly savers) are advantaged but the young (mostly borrowers) are disadvantaged. c. Workers gain because their real wages are higher than expected. d. Institutional arrangements such as tax brackets and VAT rates will be fully adjusted. 2. Which of the following statements about the Phillips curve model with expectations is correct? a. An expected high rate of inflation is associated with high levels of output and employment. b. An unexpected high rate of inflation is associated with high levels of output and employment. c. In the long run, governments can increase real output and employment by using monetary policy to increase the rate of inflation. d. In the long run, there is nothing governments can do to increase real output and employment. 3. Which of the Real revenue from the inflation tax: a. always rises as the inflation rate rises b. always falls as the inflation rate rises c. depends on the size of the government’s real deficit d. depends on the multiple of the inflation rate and the quantity of real cash. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Higher expected inflation shifts the long-run Phillips curve leftwards. 2. A positive demand shock leads to no change in the position of the short-run Phillips curve.. 3. Inflation increases the ratio of national debt to national income. 193 EC1002 Introduction to economics Long response question 1. a. What does the Phillips curve represent? Draw a diagram with a short-run Phillips curve and a long-run Phillips curve and explain why they have the shapes they do. b. Draw diagrams (explaining your answers in words at the same time) to depict what will happen to output, unemployment and the inflation rate when there is: i. a fall in the price of oil that is fully accommodated by monetary policy ii. a new, very tough and inflation-hating central bank governor appointed in a period of high inflation c. Certain types of inflation can have very serious implications. Discuss the implications of: i. negative inflation ii. hyperinflatons. 194 Block 18: Unemployment Block 18: Unemployment Introduction Until the Great Depression of the 1930s, it was generally accepted in economic theory that unemployment was solely the consequence of wages being higher than the equilibrium wage rate and that in time, wages would adjust naturally so that the labour market would clear. The events of the 1930s, including very high levels of persistent unemployment, shifted attention to the potential ‘stickiness’ of wages (i.e. the fact that wages may not fall despite high levels of unemployment) and the level of aggregate demand in the economy. This change was primarily thanks to the revolutionary ideas of British economist John Maynard Keynes, who published his best-known work The general theory of employment, interest and money in 1936. A major policy recommendation from this work was that governments should help reduce unemployment by increasing government spending to substitute for a lack of demand from private consumption and investment. A macroeconomic approach to studying unemployment thus emphasises the role of aggregate demand, especially any gaps between actual and potential output. At the same time, market imperfections which cause wages to be ‘sticky’ above the market-clearing equilibrium level are also important factors in determining the rate of unemployment in an economy. Key themes of this block thus include the different types of unemployment, as well as their causes and various policies for reducing unemployment. Although there is a positive role for short-term frictional unemployment in terms of workers moving between jobs and achieving a better skills-match, in general, unemployment is associated with large costs on both a personal and societal level. As such, low unemployment is one of the three major macroeconomic goals of economic policy, along with steady growth and low inflation. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • discuss measured unemployment, both claimant count and standardised rate • define classical, frictional, structural and demand-deficient unemployment • distinguish between voluntary and involuntary unemployment • analyse determinants of unemployment • explain how supply-side policies reduce equilibrium unemployment • evaluate private and social costs of unemployment • explain hysteresis. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 26. Synopsis of this block The textbook chapter starts by introducing basic concepts such as the labour force and the unemployment rate and provides some statistics as 195 EC1002 Introduction to economics to the composition of unemployment in the UK and the flows of people between being in employment, unemployed and out of the labour force. The various types of unemployment are introduced, notably frictional, structural, classical and demand-deficient (or cyclical) unemployment. One very important concept is the natural rate of unemployment, also known as equilibrium unemployment or the steady state rate of unemployment. Unemployment can be caused by a deficiency in aggregate demand, i.e. when there is a business cycle slump. Such unemployment can be addressed via demand-management tools, namely fiscal and monetary policy. Other types of unemployment are related to imperfections in labour markets and are better addressed by supply-side policies, such as improving information flows and reducing skills mismatches or disincentives to labour supply such as high marginal tax rates. The personal and societal costs of unemployment are also discussed, including a loss of human capital and lost output resulting from leaving resources idle. Rates of unemployment ► BVFD: read the introduction to Chapter 26. The introduction provides a brief historical background on unemployment rates for the OECD countries. Figure 26.2 shows the persistent unemployment post- 2008 recession in Ireland and Italy, for example. Do you know how unemployment has evolved in your own country? Activity SG18.1 Find out what the trend has been in the country where you live. ► BVFD: read section 26.1 and case 26.1. This section contains several important definitions – the labour force; the participation rate and the unemployment rate. The relationships between these variables can be expressed by the following equations: • Let the number of employed people be E (these are people who work for at least one hour per week). • Let the number of unemployed people be U (these are people who are actively seeking work). • Let the labour force be LF (those who are either employed or looking for work). • Let people who are not in the labour force be NFL (these are ‘inactive’ and include homemakers, students who are not working, people who are too sick to work, etc.). • Let the working age population be P: • Working-age population: P = LF + NLF • Unemployment rate: u = U/LF • Employment rate: e = E/P • Labour force participation rate: lfp = LF/P. Activity SG18.2 What is the unemployment rate in a country with a working-age population of 1,000, a labour force participation rate of 80% and 100 unemployed people? 196 Block 18: Unemployment A striking feature of Table 26.1 is the huge diversity in the experience of OECD countries (supposedly a relatively homogeneous group of countries; really poor countries and many emerging economies are not OECD members). Youth unemployment is often higher than unemployment for the labour force as a whole. Young people tend to have unemployment rates that are higher than the national average, partly because they generally have less work-experience. Following the financial crisis and European sovereign debt crisis many countries have seen extremely high levels of youth unemployment. Analysis of unemployment ► BVFD: read section 26.2. Below we take the analysis of equilibrium unemployment a bit further using the stocks and flows framework but you need also to be familiar with the graphical analysis in BVFD using the LD, AJ and LF schedules. Pay special attention to the role of rigid real wages in increasing unemployment (both equilibrium and Keynesian) within this framework. Although Figures 26.4 and 26.5 are very similar, they highlight a key distinction which is very important in the analysis of unemployment. Figure 26.4 shows how total unemployment at wage w2 (AC) is broken down into voluntary (BC) and involuntary (AB) unemployment (although, somewhat confusingly, unemployment AB is subsequently defined as being voluntary as well (with workers being part of the institutional arrangements responsible for wage w2 and its ‘stickiness’). In this case, the wage is higher than the equilibrium level due to labour market imperfections or reasons such trade union power. A rigid real wage above the equilibrium level is causing there to be both voluntary and involuntary unemployment. In Figure 26.5, the total unemployment at W* (AF) is also broken down into voluntary (EF) and involuntary (AE) unemployment, once again because of a rigid real wage above the equilibrium level. In this case, the reason is that demand for labour has fallen from LD to LD’ (but the equilibrium wage level has not fallen to W** as it is expected to in the longer term). The distance AE is demand-deficient or Keynesian unemployment. The optimal policy approaches to these two situations are quite different. In the first case, government policy should take a supply-side approach to addressing wage rigidities. This approach is discussed in section 26.3 (though the supply-side policies discussed in 26.3 also focus on bringing the AJ and LF curves closer together). On the other hand, unemployment that is caused by a deficiency in aggregate demand can be addressed via demand-management tools, namely fiscal and monetary policy. This is discussed very briefly in section 26.4. In some sense, it has been a key theme of our analysis for several chapters, as our analysis of the macroeconomy has focused on reducing or eliminating any gap between actual and potential output. Whether it is more appropriate to apply a supply-side approach or a demand management approach depends on the situation of the economy – if output is close to potential output, trying to increase demand will only lead to inflation. In this case, the best way to reduce unemployment is to focus on the supply-side. If the economy is below potential output, there is an important role for demand management to boost aggregate demand and this would be expected to bring about a substantial reduction in unemployment. 197 EC1002 Introduction to economics In the language of the diagrams described above, although involuntary unemployment could be tackled in both graphs by addressing the rigidity of the real wage such that wage levels would fall to w* in Figure 26.4 and W** in Figure 26.5, the demand-management approach is favoured in the case of demand-deficient or Keynesian unemployment, and this would be depicted by a rightward shift in the labour demand curve back to the original position at LD. Activity SG18.3 Match the concept of unemployment with its definition in the schematic below. Frictional unemployment The unemployment created when the wage is deliberately maintained above the level at which the labour supply and demand schedules intersect Structural unemployment This occurs when output is below full capacity Demand-deficient unemployment People spending short spells in unemployment as they move between jobs Classical unemployment Unemployement that arises from the mismatch of skills and job opportunities as the pattern of demand and supply changes Equilibrium unemployment (the natural rate of unemployment) Unemployed workers in the labour force who would accept a job offer at the going wage rate Voluntary unemployment The unemployment rate when the labour market is in equilibrium Involuntary unemployment Unemployed worker in the labour force who are not willing to accept a job offer at the going wage rate According to the definition in BVFD: voluntary unemployment includes frictional, structural and classical unemployment, whereas involuntary unemployment is equivalent to demand-deficient or cyclical unemployment (which is also known as Keynesian unemployment). Equilibrium unemployment/the natural rate of unemployment This rate of unemployment is also called the steady state rate of unemployment. It is the rate of unemployment such that the rate of inflow of workers into unemployment equals the rate of hiring of new workers. This means, of course, that the stock of unemployed workers remains constant. What follows is a very simple model of flows, which simplifies the stock-flow diagram of Figure 26.2 by ignoring flows into and out of the box labelled ‘Out of the labour force’ (i.e. outflows of workers from employment become unemployed and outflows from unemployment go to employment; workers who leave employment don’t leave the labour force and new employment comes from the stock of unemployed workers not from outside the labour force). If j is the rate of job loss for those with work, and h is the rate of hiring for those without jobs, and where E is the total number of employed workers and U is the total number of unemployed workers, in steady state the following must hold: jE=hU This just says that in a steady state the outflow from employment (inflow into unemployment) is equal to the inflow into employment (outflow from unemployment). Since LF = E + U (where LF is the labour force), and u = U / LF, the following equation for the steady-state rate of unemployment also holds: u = j / (j + h) 198 Block 18: Unemployment This equation is useful because it shows several things. Firstly, the natural rate rises with j and falls with h. A high rate of job loss and a low rate of hiring both increase the equilibrium unemployment rate. Secondly, 1/h is an indicator of unemployment duration. For a given level of j, a lower h means a longer spell of unemployment, as workers wait to fill a given number of vacancies.3 An increase in the duration of unemployment increases the natural rate of unemployment. Duration of unemployment is important because a given unemployment level or rate could arise from a relatively small number of individuals being unemployed for a long time or a larger number of individuals being unemployed for a short time. The implications for the individuals concerned are likely to be very different in the two cases, as are the appropriate policies that may be used to counter the unemployment. You should also remember the concept of the NAIRU from the previous block. This too is very similar to the concept of the natural rate of unemployment, although the natural rate can be seen as a more long-term concept, while the NAIRU can be interpreted as the unemployment rate consistent with steady inflation in the near term. In full equilibrium, they are the same. Activity SG18.4 In a country with a working age population equal to 25, aggregate labour demand and labour supply in an economy are summarised by the following equations: Measuring unemployment duration in practice is complicated by the fact that what we observe when we survey the unemployed are incomplete spells of unemployment whereas what we are primarily interested in (and certainly what unemployed workers are interested in) is how long a completed spell of unemployment lasts. Estimating the latter from the former raises some quite complex statistical issues. 3 Labour demand: ND = 24 – W Labour supply: NS = 3 + 2W a. Determine the equilibrium level of employment and wages as well as the unemployment and inactivity rates in equilibrium. b. Determine the unemployment and inactivity rates if the government imposed a minimum wage of £9. Changes in unemployment ► BVFD: read section 26.3. This section explores the experience of OECD countries to emphasise the point that changes in unemployment can come from (i) long- run changes in aggregate supply and equilibrium unemployment, and/or (ii) aggregate demand fluctuations. Decomposing between these two is not straightforward. If observed unemployment coincides with equilibrium unemployment then governments should not attempt to reduce it by expanding aggregate demand, but instead need to address the underlying structural factors, largely on the supply side, that determine equilibrium unemployment. This is valuable information for policy makers. Activity SG18.5 Use the (LD, AJ, LF) framework to illustrate the effects of the following supply-side factors on unemployment: a. a rise in the use of online employment websites for job search decreases skill mismatch b. a fall in unemployment benefit, decreasing the replacement rate c. a fall in trade union power d. an increase in marginal tax rates. 199 EC1002 Introduction to economics Cyclical unemployment ► BVFD: read section 26.4. The way that cyclical unemployment is defined in L&C (UK edition p.573; international edition p.473) helps to connect the analysis here with what was learned in the previous chapters – ‘Cyclical unemployment, or demand-deficient unemployment, occurs whenever there is a negative GDP gap’ (i.e. total demand is insufficient to purchase all of the economy’s potential output, causing a recessionary gap in which actual output is less than potential output). Cyclical unemployment can be measured as ‘the number of people who would be employed if the economy were at potential GDP minus the number of persons currently employed’. While section 26.3 focused on supply-side policies to address unemployment, this section discusses the use of counter-cyclical demand management policies. Keynes’ original policy recommendations to address the extremely high unemployment levels of the 1930s focused on increasing government spending to offset the lack of private consumption and investment. He argued it didn’t necessarily matter what the money was spent on (though of course he favoured productive projects) – what was important was to increase aggregate demand. This would lead to economic growth and a fall in unemployment. Keynesian ideas strongly influenced the US Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt, who embarked on extensive public works programmes including the building of roads and bridges as well as relief programmes providing housing support, food, medicines, and other basic necessities to the unemployed. The massive spending undertaken as countries invested in armaments for the Second World War has been credited with finally ending the mass unemployment of the depression years. Various countries also used expansionary fiscal policy in an attempt to re-stimulate their economies after the 2008 credit crunch. For example, the US Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 (a $152 billion stimulus consisting predominantly of $600 tax rebates to low and middle income Americans), followed by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (including direct spending on infrastructure, education, health, energy, federal tax incentives, and expansion of unemployment benefits and other social welfare provisions – with an estimated cost of $831 billion between 2009 and 2019). The Chinese government also pledged to spend 4 trillion yuan on infrastructure and social welfare by 2010. The UK also undertook a large fiscal stimulus programme, including a temporary 2.5 per cent cut in VAT (sales tax) and a car scrappage scheme similar to ones in France and Germany, although the scope for fiscal stimulus in the UK has been limited by the huge debts the government had incurred bailing out the financial sector. There is evidence that the expansionary fiscal policies employed in these countries have indeed helped to combat rising unemployment – for example, US states that increased per-capita expenditures the most, experienced the smallest rises in unemployment rates. This approach to addressing unemployment is more focused on the short run, while the supply-side policies discussed in the previous section tend to focus on reducing longer-term structural unemployment. 200 Block 18: Unemployment Cost of unemployment ► BVFD: read section 26.5 and concept 26.3. Despite the safety net that is provided in the UK by Jobseeker’s Allowance, most forms of unemployment apart from short-duration frictional unemployment are associated with large personal costs – these include a loss of income, an erosion of human capital (meaning that skills deteriorate when they are not being used) and psychic costs such as feeling rejected or not useful. Furthermore, although it is true that if unemployment is voluntary then, by definition, the private benefits of unemployment exceed the private costs, it does not follow that the voluntarily unemployed are not suffering considerable hardship. This could well be the case where the potential jobs available to the unemployed are low paid and at the same time the state pays low unemployment benefits, as measured by the replacement rate. Let us consider the case of Greece, for example. The replacement rate is comparatively low in Greece (and falls rapidly after the first year of eligibility) and the employment opportunities available to Greek workers during Greece’s recent deep recession were very limited and poorly paid. Unemployed Greek workers have had very low living standards during this period. The social costs of unemployment are also extensive, and include a loss of output and aggregate income, an increase in inequality, a loss of human capital for the society as a whole resulting in lower productivity. Hysteresis Concept 26.2 outlines four reasons why hysteresis (a temporary fall in demand inducing permanently lower output and employment) may occur and its policy implications. The existence of hysteresis is one reason why governments are so eager to prevent unemployment rising in the first place. Hysteresis also undermines the strict classical view of the natural rate of unemployment whereby fluctuations in demand affect only shortrun output, employment and unemployment, all of which return to their underlying classically-determined levels in the long run. If hysteresis could be established empirically as a significant phenomenon, and there is still controversy on this point, then recessions could raise the natural rate of unemployment, leaving the economy permanently scarred. Overview The total working-age population consists of the labour force and those who are ‘inactive’. The labour force consists of the employed plus the unemployed. The participation rate is the labour force divided by the total population. The unemployment rate is the unemployed divided by the labour force. Unemployment can be classified as frictional, structural, classical or demand-deficient unemployment. BVFD define ‘voluntary’ unemployment, or equilibrium unemployment, to include frictional, structural and classical unemployment. Involuntary unemployment is equivalent to demand-deficient unemployment, also known as cyclical or Keynesian unemployment. The natural rate of unemployment is defined as the equilibrium rate of voluntary unemployment. Temporary recessions lead to increased cyclical unemployment. This can be addressed using the demand-management tools of fiscal and monetary policy. A one per cent increase in output is likely to lead to a much smaller reduction in cyclical unemployment due to increases in hours worked by those 201 EC1002 Introduction to economics currently employed and increased numbers joining the labour force. In the long run, the only way to reduce unemployment permanently is to reduce the natural rate of unemployment through supply-side policies such as reducing mismatch through better information and retraining, reducing trade union power, cutting the marginal rate of income tax and reducing unemployment benefits (of course, society may choose a higher equilibrium rate of unemployment rather than adopt some of these policies). There is also a link between cyclical unemployment and the natural rate of unemployment, since short-run changes can move the economy to a different long-run equilibrium. This is known as hysteresis. Most forms of unemployment, apart from frictional unemployment, are associated with large personal costs including lost income, an erosion of human capital and psychic costs, as well as social costs including a loss of output and aggregate income, increased inequality, a loss of human capital for the society as a whole resulting in lower productivity, and the effects on the public finances of unemployment benefits and lost tax revenue. Low unemployment is one of the three major macroeconomic goals of many governments, along with steady growth and low inflation. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. Which of the following statements about the labour market is correct? a. The labour force consists of people who are of working age and do not have caring responsibilities. b. The participation rate is the fraction of the population of working age in the labour force. c. Structural unemployment includes people spending a short time unemployed as they move between jobs. d. Classical unemployment occurs when output is below full capacity. 2. Which of the following is not true? a. The unemployment rate is counter-cyclical. b. The average unemployment rate differs substantially across countries. c. The sign of a well-functioning economy is that there is no unemployment. 3. The fraction of employed workers who lose their jobs each month (the rate of job separation) is 0.01 and the fraction of the unemployed who find a job each month is 0.09 (the rate of job findings), then the natural rate of unemployment is: a. 1 per cent (0.01) b. 9 per cent (0.09) c. 10 per cent (0.10) d. about 11 per cent (actually, 1/9). 202 Block 18: Unemployment True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. The labour market is in equilibrium if demand for labour at the current wage is equal to the size of the labour force. 2. It is impossible to increase the level of equilibrium unemployment by improving the match between the skills employers require and the skills workers have. 3. The labour market is in equilibrium if there is zero voluntary unemployment. Long response question 1. a. Suppose that at the beginning of the month, the number employed, E, equals 180 million; the number not in the labour force, N, equals 50 million; and the number unemployed, U, equals 20 million. During the course of the month, the flows indicated below occurred: • 4.0 million – moved from employment into unemployment (EU) • 1.5 million – moved from employment to not being in the labour force (EN) • 2.2 million – moved from unemployment into employment (UE) • 2.7 million – unemployed people dropped out of the labour force (UN) • 0.3 million – moved from not being in the labour force directly into employment (NE) • 1.8 million – moved from not being in the labour force directly into unemployment (NU). i. Assuming that the population has not grown, calculate the unemployment and labour force participation rates at the beginning and end of the month. ii. Excluding movements into and out of the labour force, calculate the rate of job loss (j), and the rate or hiring (h). b. Use an appropriate graphical framework to illustrate the effects of the following supply-side factors on unemployment: i. An increase in marginal tax rates ii. A fall in unemployment benefit, decreasing the replacement rate. Food for thought – Box 6: What will the future of work look like? Working is an integral part of our lives and jobs determine our living standards, while linking us to the economic and social fabric of our country. It should therefore come as no surprise that the labour market has long been investigated by economists. Studies are not restricted to the drivers of labour market outcomes, but also try to understand how new technology (e.g. the introduction of self-driving cars), shocks (e.g. Brexit) alongside changes in preferences affect the equilibrium in different sectors. As some jobs disappear, or change radically, others are created and reach new peaks. 203 EC1002 Introduction to economics Who would have guessed 50 years ago that people in the movie industries would have found niche jobs such as environmental designers, working to build the realistic worlds we see in fantasy and action movies? Or the many tailoring shops that shut down due to the rise of inexpensive, fast fashion, brought about by the decreasing cost of fabrics and equipment needed to turn it into clothes. These changes, as have many others affecting labour markets, follow the introduction of new technology and changes in preferences. Demand for new tasks increases and people with expertise can negotiate better wages, whereas in other areas there is a fall in demand driving unemployment. Throughout history, the introduction of new technology, from the wheel to quad-core processors, has altered worker productivity, enabling the introduction of new products and driving drastic changes in the labour market. Importantly, there is a time lag between the introduction of new technologies and the creation of new industries and jobs. It may not always be fast, but it creates a fertile ground for economic research. Researchers in this field seek to forecast and alleviate the negative effects of shocks on workers in key sectors. To advise policymakers and facilitate the transition of those affected into other sectors, economists spend a large amount of time on making theoretical predictions based on theory and (perhaps an even larger amount of time) on analysing labour market data. Economics Nobel Laureate and LSE Professor Sir Christopher Pissarides (LSE) is one of the most prominent scholars to have worked on labour markets and has recently focused on the impact of automation on the creation (and destruction) of jobs. As he puts it ‘As autonomous cars develop, we’ll need to help taxi drivers retrain to work in hospitality and as the use of the internet spreads we’ll need to help call centre staff train in home care. We’ll need to make society appreciate those jobs more, make them more rewarding to hold and improve the quality of service’. He argues that good jobs are the key to happiness and that to support it countries should implement policies that facilitate (re)training of workers and mobility across sectors. The rise in automation can be an important opportunity of growth but will also cause many to lose their jobs. Economists are attempting to forecast the likely displacement of workers due to the introduction of more automation and how to limit economic harm and possible effects on inequality. Try to think about whether you would be willing to move for a job: what would induce you to leave your sector? Or your country? What would be the key benefits and costs of such a move? Read this interview with Sir Christopher Pissarides to find out more. 204 Block 19: Exchange rates and the balance of payments Block 19: Exchange rates and the balance of payments Introduction This block examines the international sector in some detail. Net exports has been part of our model of the economy since Block 11, but we have not explored it in any depth. However, interactions with other countries play an important role in almost all economies. Globalisation has meant that the world is now very integrated, such that countries cannot operate independently from each other. As well as trade flows, there are also massive capital flows in foreign exchange, shares and bonds, and other financial instruments. This block provides the tools to analyse the international sector and its impact on the domestic economy. Throughout the block, the UK is used as the ‘domestic’ economy and pound sterling as the ‘domestic’ currency. A choice had to made, but US textbooks would use the dollar as the domestic currency and Malaysian textbooks the ringgit. In following the analysis, use whatever you are most comfortable with as the domestic and foreign currencies, but always pay attention to which way the exchange rate is defined (foreign in terms of domestic or vice versa). Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • analyse the foreign exchange market • discuss balance of payments accounts • explain determinants of current account flows • define perfect capital mobility • assess speculative behaviour and capital flows • define internal and external balance • analyse the long-run equilibrium exchange rate. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 27 (except Maths A27.1). Synopsis of this block This block covers Chapter 27 of the textbook, which introduces exchange rates and the balance of payments and provides a background to the following block on open economy macroeconomics. Exchange rates – the number of units of foreign currency that exchange for a unit of the domestic currency – are determined by demand and supply in the foreign exchange market. The balance of payments consists of the current account and the capital and financial accounts. These are discussed in more detail in the block. Under floating exchange rates, the balance of payments will balance automatically, though when exchange rates are fixed, there is a need for government intervention so that the current account and capital and financial accounts offset each other. This block also introduces real and purchasing power parity exchange rates as well as the interest parity 205 EC1002 Introduction to economics condition. Finally, the block also discusses the importance of external balance as well as long-run trade balance between countries. The exchange rate ► BVFD: read section 27.1 and concept 27.1. The exchange rate is the number of units of one currency that exchange for a unit of another currency. A fall (rise) in the exchange rate is called depreciation (appreciation). The exchange rate is just a price – the price of one currency in terms of another. This price can rise or fall, like any other price. As stated above and in the text, it is important to keep track of which way round the price is expressed – the foreign value of the domestic currency or the domestic value of the foreign currency. Where we think of the exchange rate as the international or foreign price of the domestic currency a lower exchange rate makes the domestic economy more competitive (see the BVFD example of whisky with a UK price of £16 per bottle). Activity SG19.1 gives you some practice at keeping track of the sometimes confusing concept of the exchange rate. Activity SG19.1 Complete the following table: You are in Exchange Rate International value of the What does it mean? (i.e. how domestic currency, or domestic much of one currency can you price of foreign exchange? buy for the other?) UK $US1.571/£ Germany 1.244€/£ Malaysia $US0.286/MR UK £0.804/€ It is common to assume the demand for imports is elastic and draw the supply curve of currency sloping upwards. When demand for imports is elastic, a fall in the $/£ exchange rate (the pound getting weaker against the dollar) will lead to a fall in the volume of imports (since US goods are now more expensive for UK residents), and this fall in volume will be proportionately larger than the increased price of imports. Therefore, fewer pounds in total will be spent on imports. Thus there is a positive relationship between the exchange rate and the supply of pounds, and the supply curve slopes upwards (when demand for imports is elastic). Trade is often analysed as taking place between two countries (this enables use of simple diagrammatic techniques among other things) and in such case the definition of ‘the’ exchange rate is unproblematic. Concept 27.1 explains a relatively straightforward way to generalise the definition of the exchange rate to the more realistic case where a country has many trading partners – the effective exchange rate being the weighted average of individual bilateral exchange rates. The effective exchange rate is 206 Block 19: Exchange rates and the balance of payments particularly useful for tracking the strength of a currency over time. By its nature the effective exchange rate is expressed as an index, set at 100 (usually) at some chosen starting date. Fixed and floating exchange rates ► BVFD: read section 27.2. This section discusses fixed and floating exchange rates. This analysis is essentially the same as standard supply and demand analysis, except that when the price (the exchange rate) is fixed, this fixed price has to be maintained by the central bank of the domestic country buying or selling the foreign currency (although in practice the central banks of both the domestic and foreign countries may work together to maintain the fixed exchange rate). To test your understanding of the basic supply and demand framework answer the following multiple choice question. Activity SG19.2 Assume that the UK is the domestic country (and the central bank is the Bank of England) and that the exchange rate ($/£) is fixed. Supply the correct combination to fill the gaps in the following sentence. If, at the fixed exchange rate the pound (£) is ……………… the Bank of England must ……….. pounds and its dollar ($) reserves will …….. a. overvalued buy rise b. overvalued sell rise c. undervalued buy rise d. overvalued buy fall This course considers only fixed and floating exchange rates, but there are other exchange rate regimes. You are not expected to know about these for EC1002, but as an economist you should be aware of what is happening in your own country. Exchange rate regimes include (for example) a crawling peg system, where a country’s currency is pegged to the value of another currency, but the government explicitly recognises that this will be allowed to change from time to time, when needed; and a managed float, where the currency is allowed to move freely, but the government participates in the market to damp large fluctuations. Exchange rate regimes are represented below as a continuum, with the most government involvement on the left and the most market flexibility on the right. Currency Board Hong Kong, Bulgaria Currency Union Eurozone, dollarizaon Fixed Peg China, Pakistan Crawling Peg Cost Rica Managed Float India, Singapore, Russia Crawling Bands Denmark Free Float UK, USA, Sweden Figure 19.1: A continuum of exchange rate regimes. If intrested, you can find much more detail about exchange rate regimes in the IMF Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (www.elibrary-areaer.imf.org). See in particular the Country Table Matrix. 207 EC1002 Introduction to economics The balance of payments ► BVFD: read section 27.3. The balance of payments consists of the current account and the capital and financial accounts as well as any balancing item required because of statistical discrepancies. The current account records transactions arising from trade in goods and services; income (i.e. employee compensation and investment income paid to and received from people, business or assets in other countries; and transfers such as the government paying a pension to someone living abroad or people sending money to relatives abroad). The capital and financial accounts record transactions related to international movements of ownership of financial assets, such as shares, bank loans and government securities. Under floating exchange rates, there is no official financing and the balance of payments is always zero. Under fixed exchange rates the balance of payments is not necessarily equal to zero and official financing may be required to ensure that overall demand and supply of currency are equal and the fixed exchange rate is maintained. Table 27.2 helps to clarify this section. Activity SG19.3 Complete the following multiple choice questions, providing a reason for your answer. 1. The value of a country’s exports is listed in its balance of payments account as: a. a credit b. a debit c. a payment d. an investment. 2. In the balance of payments, a net inflow of capital shows up as a: a. surplus in the capital account b. deficit in the capital account c. surplus in the current account d. deficit in the current account. Real and PPP exchange rates ► BVFD: read section 27.4. It is important to make a distinction between the nominal exchange rate and the real exchange rate. The real exchange rate takes into account the differences in price levels, or the change in prices, (i.e. inflation) between countries. For clarity, note that: Real exchange rate = Nominal exchange rate × (Domestic price level / Foreign price level). This means that a rise in the domestic price level leads a rise/appreciation in the real exchange rate (if nominal exchange rates are constant). The purchasing power parity (PPP) theory holds that in the long run, the average value of the exchange rate between two currencies depends on their relative purchasing power. It should cost the same to buy a basket of goods in US dollars in the USA, as to convert the same dollars into Euros and buy that basket of goods in the EU. Otherwise, there would be an incentive to buy or sell foreign currency and take advantage of this 208 Block 19: Exchange rates and the balance of payments discrepancy. The PPP exchange rate is determined by the relative price levels in the two countries. That is why BVFD define the PPP path as ‘the hypothetical path of the nominal exchange rate that would maintain a constant real exchange rate’ (p.537). To make the theory of PPP a little more ‘digestible’, The Economist came up with the idea of the Big Mac Index in the mid-1980s. This compares the price of a McDonalds Big Mac burger in different countries and has since become a well-known, though rough and ready, indicator of currencies that are over or undervalued. Since Big Macs are produced to a certain specification but are sold at local prices, comparing the prices of Big Macs between countries and comparing this to the market exchange rate gives an indication of how far above or below a market exchange rate is from the PPP rate. This example of how the Big Mac index works looks at the exchange rate between the US dollar (USD) and the Malaysian ringgit (MYR). If the official (nominal) exchange rate was 1USD = 3.62MYR, or 1MYR = 0.28USD (28 cents). In the USA a Big Mac costs $4.79 and in Malaysia 7.63MYR, or at the nominal exchange rate 7.63/3.62 = $2.11. At these prices and the nominal exchange rate, the real exchange rate is given by1: This calculation mirrors those in Table 27.3 in BVFD. 1 real exchange rate = RER = price of Malaysian Big Mac in terms of US Big Mac or RER = = (USD/MYR nominal exchange rate)PM P US (0.28 USD/MYR)(7.63MYR/Malaysian Big Mac) (4.79USD/US Big Mac) = 0.45 US Big Macs Malaysian Big Macs (i.e. at current prices and the current nominal exchange rate) one obtains 0.45 of a US Big Mac per Malaysian Big Mac. If the exchange rate reflected PPP a Big Mac would cost the same in both countries. Clearly, at the nominal exchange rate a Big Mac is much cheaper in Malaysia than in the USA. In fact, one can get 2.27 (4.79/2.11) Big Macs in Malaysia for each US Big Mac. What does this say about the value of the Malaysian ringgit versus the US dollar? It tells us that the ringgit is undervalued. To see this, imagine Malaysia could export its Big Macs to the USA and sell them for $2.11 (transport costs and food decay are ignored here just to illustrate the basic principle). There would be a big demand for ringgits by US importers and this would bid up the dollar price of ringgits. Americans would have to pay more dollars for their ringgits. How much more? This question is answered by calculating x in 7.63x = 4.79. x is the dollar cost of a MYR, and the equation calculates what this would have to be in order for an imported Big Mac to cost the same as a domestically made one. The answer is $0.63 (63 cents). When the dollar value of the ringgit increases from 28 to 63 cents it is no longer advantageous to import Big Macs from Malaysia. Equivalently, while the nominal exchange rate is 1USD = 3.62MYR, the implied PPP exchange rate is 1USD = 1.59MYR (1/0.63). At the current nominal exchange rate the ringgit is undervalued by (3.62 – 1.59)/3.62 (i.e. 56 per cent). While this is an oversimplified example, it would not be sensible to defend the precise 56 per cent undervaluation too strongly; among other shortcomings of our example, transport costs cannot be ignored, nor can trade barriers and in calculating PPP one needs to use the price of basket commodities not just the price of a Big Mac. However, the basic lesson is that calculations of real exchange rates can tell us whether nominal exchange rates fundamentally undervalue or overvalue a currency and consequently whether there is pressure for the currency to appreciate or depreciate. 209 EC1002 Introduction to economics For more information on this see: www.economist.com/content/big-macindex Using the PPP exchange rate, rather than $US for example, helps provide a better understanding of the standard of living in each country. Non-traded goods and services tend to be cheaper in low-income than in high-income countries and any analysis that doesn’t take these differences into account will tend to underestimate the purchasing power of consumers in emerging market and developing countries and, consequently, their overall welfare. The current and financial accounts ► BVFD: read sections 27.5 and 27.6 as well as case 27.1. The balance of payments consists of the current account, the capital account and the financial account (ignoring the statistical discrepancy). Under floating exchange rates, the current account is exactly equal and opposite in sign to the sum of the capital and financial accounts. Section 27.5 discusses the current account. The capital account is generally very small and is not discussed here. Section 27.6 discusses the financial account. To understand section 27.5 on the determinants of the current account, you should be clear on the relation between the real exchange rate (RER) and exports (X) and imports (Z). The lower the RER, the cheaper are domestic goods relative to foreign goods; this increases exports and decreases imports. If you understand this you will see that the following relationship exists between the RER and net exports (X – Z), again taking the UK as the domestic and the USA as the foreign country (this diagram is essentially the same as Figure 27.4 in BVFD): RER ($/£) X-Z Figure 19.2: Relationship between RER and net exports. The volume of forex traded internationally is many times as great as global GDP. While some of this is required for international trade in goods and services, it has been estimated that at least 80% of the global currency market consists of exchange rate speculation. Speculation can lead to a lot of volatility and it is argued that it has been one of the major causes of several large financial crises such as those in Mexico (1994), South East Asia (1997–98), Russia (1998), Brazil (1999), Turkey (2000) and Argentina (2001). Investors move funds one country to another in response to different interest rates in the two countries and expected movements in the exchange rate. Starting with £1, you can invest it in the UK and get the UK rate of interest. Alternatively, you can use the £1 to buy dollars, invest them in the USA, getting the US rate of interest, and then sell the 210 Block 19: Exchange rates and the balance of payments dollars to get pounds. If you could be sure that the exchange rate would not change between when you buy and sell the dollars you would put your money in whichever country had the higher rate of interest. If you were certain about what the exchange rate was going to do you could take this into account when comparing the two investment strategies. Doing the mathematics of this gives you what are called interest parity conditions. You are not expected to know about interest parity for this course; it is covered in EC2065 Macroeconomics. Maths A27.1 is not on the syllabus of EC1002. Long-run equilibrium ► BVFD: read sections 24.7 and 24.8. BVFD argue that in long-run equilibrium, both internal and external balance must hold. The long-run equilibrium exchange rate must thus be compatible with internal and external balance. The next chapter, on open economy macroeconomics, takes this assumption as the basis for much of the reasoning. However, long-run equilibrium is an analytical construct not often approached in reality. In practice it can be argued that a current account deficit is neither intrinsically ‘good’ nor ‘bad’. There are countries such as Australia (a small open economy) which have sustained current account deficits for several decades. The IMF writes that ‘whether a country should run a current account deficit (borrow more) depends on the extent of its foreign liabilities (its external debt) and on whether the borrowing will be financing investment that has a higher marginal product than the interest rate (or rate of return) the country has to pay on its foreign liabilities’.3 This means that running a current account deficit (investing more than is saved domestically) can be a good idea, even in the longterm, if it is manageable and the incoming capital flows are being invested productively, generating more wealth for the next generation out of which the country’s debts can be repaid. www.imf.org/external/ pubs/ft/fandd/basics/ current.htm 3 Despite this, external balance is nonetheless important in the sense that global imbalances can have severe consequences. For example, it is thought that the current imbalance between the USA and China – where the USA has massive trade deficits and China has massive trade surpluses (partly a result of the undervalued Chinese yuan) – helped establish the conditions which contributed to the recent financial crisis. The following block (covering textbook Chapter 25) focuses on internal and external balance as a way of examining the effects of various fiscal and monetary policy stances under different types of exchange rate mechanisms and different assumptions concerning capital mobility. ► BVFD: read the summary and work through the review questions. Overview This block firstly introduces exchange rates, which express the price of one country’s currency in terms of another country’s currency. Exchange rates are determined by the supply and demand for currency, arising from exports/imports and trade in assets. Floating exchange rates equate demand and supply, while fixed exchange rates require government intervention in the forex market (buying or selling domestic or foreign 211 EC1002 Introduction to economics currency) so that supply and demand are equated. The real exchange rate takes into consideration the domestic and international price levels. The balance of payments consists of the current, financial and capital accounts. Monetary inflows are recorded as credits and outflows as debits. Under floating exchange rates, the balance of payments is always zero. A current account deficit is balanced by a surplus in the capital and financial account. Under fixed exchange rates, the government may have to intervene in the forex market to offset a balance of payments surplus or deficit – this is called official financing. The current account consists primarily of imports and exports and is determined by the real exchange rate (a rise in the real exchange rate reduces domestic competitiveness and the demand for exports) as well as domestic and foreign incomes. In practice, the capital and financial accounts are dominated by speculative flows of currency seeking the highest return. As well as achieving internal balance (full employment and stable prices), governments are also concerned with achieving external balance (a balanced or at least manageable balance of payments). There is a single long-run equilibrium real exchange rate that is compatible with internal and external balance. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. In an economy with a fixed exchange rate policy, when both capital and current accounts are in surplus: a. The balance of payments will be balanced through a decrease in foreign exchange reserves and there will be an increase in the supply of domestic currency. b. The balance of payments will be balanced through an increase in foreign exchange reserves and there will be an increase in the supply of domestic currency. c. The balance of payments will be balanced through an increase in foreign exchange reserves and there will be a decrease in the supply of domestic currency. d. The balance of payments will be balanced through a decrease in foreign exchange reserves and there will be a decrease in the supply of domestic currency. 3. Assuming there is perfect capital mobility, according to the interest parity condition, an increase in the domestic inflation rate relative to other countries would lead to: a. an increase in competitiveness b. a decrease in the exchange rate c. a surplus on the current account d. none of the above. 212 Block 19: Exchange rates and the balance of payments True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. If a Dominican businessperson exports goods and services to Cuba, this will show up in the balance of payments of both countries; however, the money spent by a Dominican taking a vacation in Cuba only shows up in the balance of payments of the Dominican Republic. 2. In Eritrea the exchange rate between the Nakfa and the U.S. dollar is fixed. If, at the fixed exchange rate the Nakfa is overvalued, the Eritrean central bank needs to buy Nakfas and lower its reserves of dollars to restore the equilibrium. 3. The UK has a floating exchange rate. If all transactions between the UK and the rest of the world are correctly measured, then the UK balance of payments is equal to zero. Long response question 1. a. Draw a graph of the supply and demand curves for the foreign exchange market, expressed in terms of pesos per dollar. Show the equilibrium price at 5 pesos per dollar. Suppose the demand for dollars increases so that the new exchange rate is 7 pesos per dollar. Has the peso appreciated or depreciated? Which currency has strengthened? Is this good or bad for the USA? For Mexico? b. Suppose the following data represent Mexico’s international transactions measured in millions of pesos. Merchandise exports 15 Merchandise imports 10 Change in foreign assets in Mexico 12 Change in assets abroad 8 Exports of services 7 Imports of services 5 Income receipts on investment 5 Income payments on investment 10 Unilateral transfers 6 i. What is Mexico’s trade balance? ii. What is the balance on its current account? iii. What is the balance on its capital account? iv. What kind of exchange rate regime is Mexico operating? 213 EC1002 Introduction to economics Notes 214 Block 20: Open economy macroeconomics Block 20: Open economy macroeconomics Introduction Having been introduced to fixed and floating exchange rates in the previous block, this block examines the workings of the economy under different exchange rate regimes, as well as different assumptions regarding capital mobility. Although there is some discussion of adjustment to other shocks, the focus of this block is on macroeconomic policy – the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary under different exchange rate regimes and assumptions about capital mobility. You will see that the exchange rate regime a country adopts has a profound impact on the way the economy operates and how it can be managed. Learning outcomes By the end of this block and having completed the Essential reading and activities, you should be able to: • describe monetary and fiscal policy under fixed exchange rates • explain the effects of a devaluation • describe monetary and fiscal policy uner flexible exchange rates. Essential reading Begg, Vernasca, Fischer and Dornbusch (BVFD), Chapter 28 (except Maths 28.1). Synopsis of this block This block examines how the economy operates under different exchange rate regimes – namely, fixed and floating exchange rates, and discusses the important effects of capital mobility. Furthermore, this block makes use of IS-LM-BP analysis to illustrate the effects of fiscal and monetary policy under fixed and floating exchange rates. The block starts by discussing fixed exchange rates and macroeconomic policy under fixed exchange rates, then discusses devaluation – an occasional adjustment in an exchange rate that is pegged at a fixed value. Finally, floating exchange rates are examined, including what determines the level and fluctuations in these rates as well as the operation of macroeconomic policy when exchange rates are flexible. The macroeconomy under fixed exchange rates ► BVFD: read section 28.1, 28.2 and case 28.1. The choice of exchange rate regime affects the way in which monetary and fiscal policy transmits in the economy. On the aggregate demand side we have net exports that also determine the current account of the balance of payments. An important determinant of the effect of monetary and fiscal policy under a particular exchange rate regime is the capital account and the degree to which capital is internationally mobile. High levels of capital mobility can be destabilising if a country has an exchange rate peg, which is why in the post war period (1945 to 1973) when exchange rates were fixed these 215 EC1002 Introduction to economics were paired with capital controls. If investors have more funds than the central bank then it is not possible to defend a peg. We distinguish between different degrees of capital mobility. In one extreme of the spectrum is perfect capital mobility, where capital is free to move and is thus incredibly sensitive to interest rate differentials between countries – as capital flight occurs as investors seek out the higher interest rate on their assets. On the other is regulated capital controls that prevent private sector capital from flowing between different currencies. Perfect capital mobility is essentially a commitment to maintain interest rate parity with the foreign economy, so as to prevent largescale capital inflows or outflows. Essentially, therefore, the MP curve becomes horizontal at the foreign interest rate i^*under a fixed exchange rate with perfect capital mobility. External balance dictates a horizontal MP. The implication of this is that fiscal policy is extremely effective under a fixed exchange rate regime with perfect capital mobility. Consider a diagram such as Figure 28.1 but modify it such that the MP curve is horizontal. If there is a fiscal expansion (or contraction the), the IS shifts to the right (or left), causing domestic income to rise (or fall). The effect is far larger than in a closed economy because of the fact that there is no crowding out of consumption and investment. This corresponds to a movement from A to B in Figure 28.1. Suppose instead that capital mobility was low, so capital flows would be small in scale. It would be possible to maintain an upward sloping MP schedule as in Figure 28.1. An interest rate differential could be sustained between countries as capital flows are restricted to an extent, giving rise to a smaller impact on income of A to C in Figure 28.1. What of monetary policy? Central banks cannot implement monetary policy under a fixed exchange rate and perfect capital mobility! This is because the interest rate is pinned down by the overseas interest rate i^* . If they were to try and tighten monetary policy, for example, shifting the MP upwards, the interest rate domestically would rise above the foreign interest rate (internal balance), attracting large scale capital inflows. The central bank would have to intervene in the foreign exchange market to sell domestic currency demanded by investors, thereby increasing the money supply and restoring MP to its initial position. In summary, under a fixed exchange rate regime and perfect capital mobility fiscal policy is very effective while monetary policy is entirely ineffective. Later in the section the BVFD textbook uses the AD framework to examine the effect of shocks on the macroeconomy, though the focus of this block is the impact of openness and the exchange regime on policy effectiveness. framework, which relies on changes in domestic inflation altering the real exchange rate (even though the nominal exchange rate is fixed) and thus international competitiveness. This is summarised in Figure 25.2. Devalution of a fixed exchange rate ► BVFD: read section 28.3. This section discusses the impact of a devaluation of a pegged exchange rate in the short, medium and long run. Devaluation may be a useful tool in response to a shock to the trade balance. It can help to achieve positive outcomes more quickly than through a slump in the domestic economy. 216 Block 20: Open economy macroeconomics Balance of payments current account The J-curve – This describes how a devaluation of a fixed exchange rate may initially lead to a deterioration in the country’s current account because the money value of imports rises while the domestic price of exports remains steady. In time, however, once quantities begin to adjust to the increased competitiveness brought about by the reduction in the real exchange rate, the trade balance will improve. Examining trade balance over time thus gives rise to a J-shaped curve (see footnote 4 in BVFD p.555). This is demonstrated by Figure 20.3 below. As an example, after the 1967 devaluation of pound sterling, it took between 18 and 24 months for the UK current account to move into surplus. + 0 t0 - Time Figure 20.3: J-curve. It is important to realise, however, that although countries are likely to see an improvement in the trade balance in the medium term, in the long run, devaluation has no real effect. As is mentioned in BVFD, empirical evidence suggests that increases in domestic prices and wages tend to offset the effects of the devaluation within four or five years. Looking at Figure 25.3, the graph of the current account (value) initially shows the J-curve shape as in the figure above, but then drops down again and levels out in the longer term. In general – nominal change will not bring about real change. Activity SG20.1 What policy measures should accompany a devaluation of a pegged exchange rate to ensure optimal results in the medium term? Under what circumstances is a devaluation likely to have the most positive impact on the economy? The macroeconomy under floating exchange rates ► BVFD: read section 28.4 and 28.5. Under floating exchange rates the way the macroeconomy works is quite different. Foreign reserves stay constant, the balance of payments is zero and there is no need for foreign exchange intervention. As discussed in BVFD section 28.4, in the long run, floating exchange rates adjust to achieve the unique real exchange rate compatible with internal and external balance’. However, in the short run, exchange rates can be very volatile. They respond to current interest rate differentials and inflation differentials between countries, expectations regarding the future long-run value of the exchange rate and new information which changes people’s 217 EC1002 Introduction to economics expectations regarding interest rates, inflation or the long-run equilibrium exchange rate. In working through the explanation of Figure 28.4 remember that the key assumptions are first that there are no long-run differences in interest rates between countries and second that adjustment of the exchange rate to eliminate interest rate differentials follows interest rate parity, with positive (negative) interest rate differentials offset by expected and then actual currency depreciation. As interest rate parity is not in the EC1002 syllabus, we focus discussion to the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy under a floating exchange rate. In a closed economy we analysed the effect of policy using the IS-MP framework. We can do so here also, but factoring in that aggregate demand that underpins the IS curve includes net exports (current account), which adjusts with exchange rate movements. At the same time, the exchange rate must adjust adjust to present massive capital flows in response to interest rate changes in order to ensure external balance is maintained. Let us consider the effect of monetary policy under floating exchange rates. Tighter monetary policy would cause the MP to shift up, raising the domestic interest rate (internal balance is where IS = MP). The higher interest rate attracts capital so the demand for the domestic currency rises as investors seek to purchase domestic assets. This, in turn, causes the exchange rate to appreciate, lowering net exports, shifting the IS leftwards, moderating the effect of the interest rate, but reinforcing the effect of the tighter monetary policy stance on domestic income. The exchange rate movement impacts competitiveness and the short run adjustment of the IS through the trade balance reinforces the monetary policy adjustment making it very effective. In contrast, fiscal policy is undermined by changes to the exchange rate (i.e. competitiveness) in an open economy with a floating exchange rate regime. Consider a fiscal expansion, which would raise the domestic interest rate as IS shifts to the right. This would attract foreign capital, putting pressure on the exchange rate to depreciate, which would reduce the trade balance, shifting the IS leftwards again. So, in the short run, monetary policy is powerful under flexible exchange rates, but the effectiveness of fiscal policy is reduced. It is important to realise that when the government fixes the exchange rate, they lose autonomy over the interest rate. Equally, when the government fixes the interest rate, they lose autonomy over the exchange rate. The exchange rate adjusts to prevent massive capital flows in response to interest rate changes. Exchange rates also serve as a monetary policy instrument. For example, Singapore uses the exchange rate as its primary tool for conducting monetary policy. It manages the exchange rate through direct intervention in the foreign exchange market (operating a managed float regime where the trade weighted exchange rate for the Singapore dollar is allowed to fluctuate within a policy band) and lets domestic interest rates move freely according to market forces. This stands in contrast to ‘standard’ monetary policy as implemented in most other countries, where interest rates are the key tool. This has proven to be a very effective approach for Singapore, which has a small, very open economy. ► BVFD: complete activity 28.1, read the summary and work through the review questions. 218 Block 20: Open economy macroeconomics Overview A country’s exchange rate regime has a profound effect on the way the economy operates, though this depends on the size and openness of the economy. Openness is often measured by the size of exports relative to GDP. However, capital flows also have a big impact. Capital can either be perfectly mobile, perfectly immobile (due to capital controls) or partially mobile (such as when foreign and domestic assets are not perfect substitutes). The impact of various shocks and the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy depend crucially on whether there is a fixed or floating exchange rate regime. Under fixed exchange rates and perfect capital mobility, there is no scope for monetary policy to influence the domestic economy, since the domestic interest rate must match foreign rates to prevent massive capital inflows and outflows. In the long run, internal and external balance may be restored without policy intervention through changes in prices and output. Fiscal policy is a powerful tool in the context of fixed exchange rates and capital mobility, since interest rates must remain stable and there is no crowding out of private consumption or investment. The level of fixed exchange rates can sometimes be changed – this is either a revaluation (rise in value) or a devaluation (fall in value) of the exchange rate. A devaluation improves competitiveness in the short run but is unlikely to have a large effect in the long run, though it can help speed up adjustment to shocks. A floating exchange rate must begin at a level from which the anticipated convergent path to its long-run equilibrium continuously provides capital gains or losses to offset expected interest rate differentials. The actual path of nominal exchange rates reflects changing beliefs about the future course of domestic and foreign exchange rates and the eventual level of the longrun exchange rate. Under floating exchange rates, the effectiveness of fiscal policy is limited, but monetary policy is a powerful tool. Monetary policy impacts on aggregate demand through consumption and investment (as in a closed economy) and also through its impact on the exchange rate and competitiveness. Reminder of learning outcomes Now go back to the list of learning outcomes at the start of the block and be sure that they have been achieved. Sample questions Multiple choice questions For each question, choose the correct response: 1. Suppose we have flexible exchange rates and the current account is +50. Then the capital account: a. is –50 b. depends on the level of sterilisation c. depends on the balance of payments d. depends on the amount of foreign exchange reserve accumulation. 219 EC1002 Introduction to economics 2. A number of countries in Europe have adopted a single currency, the Euro. One potential drawback of a single currency for these countries is: a. Fiscal expansions are no longer effective. b. They no longer have control over interest rates. c. Their exchange rates will now be more volatile, therefore reducing trade. d. Capital account deficits will increase. 3. The UK has a floating exchange rate and capital mobility. The exchange rate between the US dollar and the UK pound changed from $1.48 dollars per pound on 23 June 2016 to $1.36 dollars per pound on 24 June 24th 2016 following the vote to leave the European Union. Which of the following statements is correct? a. The UK pound appreciated relative to the US dollar. b. The change in the exchange rate makes it less expensive for UK residents to buy goods manufactured in the USA. c. The change in the exchange rate makes exporting to the USA more attractive for UK based firms. d. The change in the exchange rate is likely to decrease the rate of inflation in the UK. True/False/Uncertain For each of the following indicate whether the statements are true, false, or uncertain, supporting your answer with a brief explanation. 1. Fiscal policy is always more effective than monetary policy as a tool to stabilize output in an open economy. 2. Monetary policy is more effective in influencing national income when capital is perfectly immobile internationally than when capital is perfectly mobile. Long response questions 1. In an open economy with a fixed exchange rate and perfect capital mobility, a mortgage crisis leads to a fall in consumer spending a. How does the economy come back to internal and external balance if the government does not intervene? Explain the process in words and illustrate graphically. b. What would be the impact of an expansionary monetary policy? Explain in words and illustrate graphically. c. What would be the impact of an expansionary fiscal policy? Explain in words and illustrate graphically. d. Now assume the exchange rate is flexible, what would be the most effective macro policy for the government to employ? Explain in words and illustrate graphically. 2. China’s economy has been experiencing an investment and export boom that has pulled the unemployment rate well below the NAIRU. The country also has a substantial current account surplus as well as a significant capital account surplus, a fixed exchange rate, and relative capital immobility. The Peoples Bank of China (PBOC), China’s central bank, always sterilises any foreign exchange market intervention that it undertakes. The Chinese government is worried about overinvestment in many industries and rising inflation. 220 Block 20: Open economy macroeconomics a. One alternative (Scenario #1) for dealing with these concerns is to have the PBOC use monetary policy to stabilise the economy at potential output. Based only on this information, and making sure to provide an explanation, use a standard IS-LM-BP model diagram to accurately and clearly show: i. China’s initial economic situation. ii. What happens to equilibrium income, interest rates, and the balance of payments if the PBOC uses monetary policy to stabilise the economy at potential output. b. Re-draw your initial diagram. A second alternative (Scenario #2) for dealing with over-investment and rising inflation is for the government to let the exchange rate freely float, assuming that this would return the economy to potential output. Based only on this information, use a second standard IS-LM-BP model diagram to accurately and clearly show: i. China’s initial economic situation, and what happens to equilibrium, interest rates, and the balance of payments if the Chinese government allows that exchange rate to become completely flexible. c. For each of the following variables, identify whether it is higher, lower, the same, or indeterminate in Scenario #1 (monetary policy) when compared to Scenario #2 (flexible exchange rate): i. equilibrium income ii. interest rates iii. investment iv. net exports v. the exchange rate vi. the balance of payments. 221 EC1002 Introduction to economics Notes 222