Citizen Participation in Community Development: Challenges & Roles

advertisement

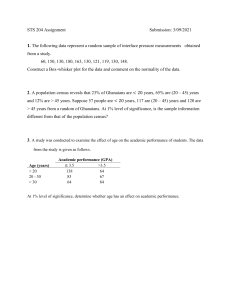

INTRODUCTION The term citizen has an inherently political meaning. It implies a certain type of relationship between people and government. Intrinsically, participation embodies fundamental democratic values, such as freedom of speech and assembly. Instrumentally, organized citizen participation can influence the development of norms and practices and the behavior of institutions through advocacy, awareness raising and monitoring efforts. The type and quality of participation matters greatly for democratization. Ideally, participation activates citizens, creates relationships with decision makers, and promotes an appropriate balance of power between citizens and government. The implementation of the public participation process is important for the democratization of social values and better planning and fulfilment of public needs. It is also useful for educating the public especially regarding government development programmes. This will potentially influence social or personal changes amongst community members, which can then be used to incorporate diverse public interests and thus accord people with the right to participate in decisions that will affect their lives. By participating in the decision making process, the public will realize the importance of their involvement in deciding their future (Chadwick, 2017). According to Slocum and Thomas-Slayter (2015), public participation is a means to convey individual and the society’s personal interests and concerns with regard to the development plans, given that these planning activities would consequently affect the public generally and certain groups specifically. According to Beierle (2018), public participation exists in the form of ‘traditional participatory for example public hearings, notice and comment procedures as well as advisory committees. In addition, public participation includes regulatory negotiations, mediations and citizen juries’. Other than serving as a means of educating people and enhancing their awareness, public participation is also vital in preparing an efficiently better planning framework as a result of better understanding of stakeholders’ demands and needs which thus leads to effective resource planning and management. Interestingly, the act of participating in structuring the development plan enables the citizens to minimise political and administration problems while promoting transparency within the professionals’ environment (Lukensmeyer, Goldman & Stern, 2011), which in turn will address perceptions of inequality of power. Participatory governance has a long history in development tracing from the post-colonial era after the abolition of the slave trade through the 1970s when the Bretton wood institutions began to recognize the involvement of beneficiaries in the design and implementation of its projects and programs. The World Bank defines Participation as a process through which stakeholders influence and share control over development initiatives, decisions and resources which affect them. Gadzekpo also define ‘participation’ as ‘ranging from information-sharing and consultation methods, to mechanisms for collaboration and empowerment that give stakeholders more influence and control’ (Gadzekpo, 2018). Participation has been largely electoral participation of the citizenry in local government and the incidence of effective participation of the citizenry in practice has been rather tokenistic. Restoring the confidence of the citizens in local government and the decentralised process in Ghana requires major attempts to drag in the citizens’ to participate not only in elections but also in its active workings. In this regard, citizens’ participation in planning administration in general has been recommended. Section 16 of the Local Government Act 1993 states that elected Assembly members are required to: meet his electorate before each meeting of the District Assembly’; ‘maintain close contact with his electoral area, consult his people on issues to be discussed in the District Assembly and collate their views, opinions and proposals and present [these] to the District Assembly’; ‘report to his electorate the general decisions of the District Assembly and its Executive Committee and the actions he has taken to solve problems raised by residents in his electoral area’. As part of the benefits of participation, the World Bank found that projects and developments stood a better chance of success if people were involved. By 2015, the bank began to advocate for ‘community-driven development’ and ‘empowerment’. Improving on citizen centric policy deliberation and service delivery and ensuring that citizens’ voices can be heard are ways for governments to improve service delivery and build public trust in state institutions. Citizen engagement also allow to broaden the development dialogue to include the views and perspectives of traditionally marginalized groups, leading to more inclusive institutions governments, development organizations, and donor agencies alike. This can strengthen public consensus for important reforms, and provide the broad political support and public ownership necessary to sustain them (Huber, Rueschemeyer and Stephens, 2017). While normative arrangements exist for the involvement of local citizens, the practicalities of local and national conditions and the political gymnastics of actors have culminated in the interest of locals being subdued. This paper therefore seeks to investigate the challenges people face in carrying out their roles as active, participatory, responsible citizens in the community. Statement of the Problem The implementation of the public participation process is important for the democratisation of social values and better planning and fulfilment of public needs. The public participation process, however, is sometimes threatened by bureaucratic constraints caused by the lack of a systematic approach and an inadequate public administration system, which contribute to the public exclusion from the process. The exclusion is also caused by the lack of knowledge about public participation and low levels of education amongst the public. Although there is a strong case for popular participation in the communities and governance space in Ghana, there are major limitations to this process. The goals of community development should be to improve people’s productivity and enable them to participate in their social, political and economic life. Some problems and challenges could be encountered in the process of seeking for success in participation in community development in the country. Though there is freedom of expression and association in the political environment, most Ghanaians do not take advantage of these fundamental rights2. Quite alarming, most Ghanaians are not ready to exercise the right to embark on demonstration or protest marches or even let their voices be heard. The overwhelming majority of Ghanaians (95 percent) have not participated in protest marches for a period of twelve (12) months, according to an Afrobarometer report released in 2014. This figure included 84 percent who say they will never do such a thing. Only 4 percent of Ghanaians have engaged in this kind of collective action “once/twice”, “several times” or “often” in the past year. Similar to the low ratings for engagement in collective action and participation in a political party, and working for a party/candidate and attending campaign rally, Ghanaians have low contact rates with both formal and informal leaders. According to the Afrobarometer Report, 2014, the low levels of contact with formal and informal leaders may be explained by Ghanaians’ perception of leaders’ responsiveness to citizen engagement. Evidence from the report further indicates that over half of Ghanaians think Members of Parliament (63 percent) and local government councilors (53 percent) never listen to what ordinary citizens have to say. Thus, there is a growing sub-culture of voice without accountability between citizens and governments contributing to the relatively low level of interest among citizens in the governance process. According to Chambers (2014) there are several obstacles and challenges combined to hinder the effectiveness of citizens contribution and participation for community development which includes inadequate financial resources, economic and social inequality and others. More so, according to Cornwall (2016) the recognition and importance of participatory citizens in the development process is prompted by the need to tackle local socio-economic problems and to manage participatory development. In most of the developing countries, including Ghana, decentralization and participation does not solve the various problems faced by the populace as local governments are facing a series of challenges in implementing community development plans and programs. People are not very clear about the nation and the community development programs. This usually leads to lack of commitment on the part of people. It is more of governmental program than that of the people. Lack of proper plan monitoring and evaluation, hence there is no systematic way of determining program accomplishment facilitating effectiveness and efficiency. Role of Citizens Since individuals constitute society, they form the units of society. As a member of society of a state a man must behave in way which is good for all and which is helpful in promoting the welfare of society. Society calls upon the individuals to follow certain norms. Some of the roles of citizens are; i. Obey to constitutions of the state. ii. Pay taxes honestly and regularly. iii. To remain loyal to our country and defend the country. iv. To uphold and protect the sovereignty, unity and integrity of the country. Challenges People Face In Carrying Out Their Roles From the public’s perspective, the act of inviting to engage in the decision making process is considered as a sign of acceptance by the government. The public is affected by the related development plan proposal, and is within the public’s interest to allow participation in the decision making process from the early stage of related planning procedure as this will encourage citizens’ input in the planning process and present the views of the entire community on specific issues to ensure the proposed plan will mirror their aspirations. In a broader sense, appropriate public participation is a key towards sustainable development given that the proposed development will be structured based on the stakeholders’ demands and needs, which include the benefits for future generations. However, at the heart of this matter rests the issue of conditions that might constrain achieving appropriate public participation. It is learned that public participation efficiency and effectiveness might be compromised by the difficulties faced by the public when it comes to understanding the technical reports and the complex planning issues (Jenkins, 2016). This will consequently affect the public’s ability to comprehend the decision making process. According to Bramwell and Sharman (2018), effective public participation is difficult to achieve if the residents are not equally represented within or as part of the whole group of stakeholders. Equal representation refers to the stakeholders’ knowledge and understanding on the proposed development specifically and knowledge in planning generally. Another challenge is the issue of apathy. Though there is freedom of expression and association in the Ghanaian environment, most citizens do not take advantage of these fundamental rights. Ghanaians have low contact rates with both formal and informal leaders. According to the Afrobarometer Report, 20143, the low levels of contact with formal and informal leaders may be explained by Ghanaians’ perception of leaders’ responsiveness to citizen engagement. Evidence from the report further indicates that over half of Ghanaians think Members of Parliament (63 percent) and local government councilors (53 percent) never listen to what ordinary citizens have to say. Finally is the lack of enforcement and sanctions on existing policy frameworks on citizen participation. Ghana abounds with a number of policies and regulations aimed at enhancing citizen’s participation in governance at all levels. As mentioned, participation is an inalienable right under the 1992 Constitution, the Local Government Act (Act 936) and most recently, the Right to Information Act. These notwithstanding, implementation of the Local Government Act shows severe deficits with regards to citizens’ participation and engagement. Whilst there are forums for consultation, they seem to be poorly supported or inactive. Thus, MMDAs hardly prioritize citizens’ participation in their operations including the local budget. For example, the conduct of public hearing as required under the planning systems and regulations as part of the preparation of the Medium Term Development Plans (MTDPs) for MMDAs rarely takes place at the local level (Gadzekpo, 2018). Quite understandably, the political actors appear to be more interested and focused on the implementation of physical projects for purpose of electoral campaign and responding to manifesto promises. Some District Assemblies are also not economically viable to raise enough from the internally generated funds to finance its program aimed at engaging the citizens at the local level. Recommendations on how to Promote Active, Participatory and Responsible Citizenship The following are recommended; First, strengthening multi-stakeholder engagement at the local level for more community participation and capacity and the inclusion of marginalized groups. The various communities in the country need to take a well-informed approach to insure that there is citizen an increased participation of community people in driving their development. Furthermore, women’s equal participation in decision-making and representation in government. Women’s unique perception lack representation in governance issue. Because of this, the interest of women are under-represented. To enhance this, the government through the roles of local government can insure that there is an aggressive approach towards women empowerment in a bit to build a well-balanced society were view of both women and men are respected despite their financial status. Finally, there is need for the government to build good political will in all sections of the public sector where there is no conflict between expected standards of leadership to the political position. People gain political power without the illegibility to lead the public offices. When good political will is created, moral obligations are going to be prioritised in a bid to reduce corruption which may highly enhance efficiency and productivity. References Afrobarometer Briefing Paper No. 137, “The Practice of Democracy in Ghana: Beyond the Formal Framework” by Daniel Armah-Attoh and Anna Robertson, March 2014 Andrea Cornwall (2006): Historical perspectives on participation in development, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 44:1, 62-83 Audrey Gadzekpo, (2018), “Guardians of Democracy: The Media”, in B. Agyemang Duah,(ed), Ghana: Governance in the Fourth Republic, The Ghana Center for Democratic Development, Accra Beierle, Thomas C. (2018). Framework for Evaluating Public Participation Pro- grams.Discussion Paper 99-06. Resources for the Future, Washington, D. C Bramwell, B. & Sharman, A. (2018). Approach to sustainable tourism planning and community participation: the case of Hope Valley, in: Greg, R. & Derek, H.(Eds.). Tourism and Sustainable Community Development (pp. 17-35). London: Routledge. Chadwick, G. (2017). Systems View of Planning: Towards a Theory of the Urban and Regional Planning Process. New York: Pergamon Press. Chambers, R. (2014) “Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA): Analysis of Experience”. World Development, vol 22, no 9, pp. 1253–1268. Huber, E., Rueschemeyer, D., and Stephens, J. D. (2017) “The Paradoxes of Cotemporary Democracy: Formal, Participatory, and Social Dimensions” Comparative Politics, Vol. 29, No. 3, Transitions to Democracy: A Special Issue in Memory of Dankwart A. Rustow (Apr., 2017), 323-34 Jenkins, J. (2016). Tourism policy in rural New South Wales: policies and research priorities. Geojournal, 29: 281-290. Lukensmeyer, C., J.; Goldman, J. & Stern, D. (2011). Assessing public participation in an open government era: a review of federal agency plans. Fostering Transparency and Democracy Series. IBM Centre for the Business of Government. Slocum, R. & Thomas-Slayter, B. (2015). Participation, empowerment and sustainable development, in: Rachel, S.; Lori, W.; Dianne, R.; Barbara, T. S. (Eds.). Power, Process and Participation: Tools for Change (pp. 3-8). London: Intermediate Technology Publications.