Financial Reporting & Performance Measurement Lecture Notes

advertisement

FINANCIAL REPORTING AND PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT

Week 1 - 19 September 2022

AMAZON

His recent stock price: 123,17$

Stock price: it tells you a company current’s value or its market value. It represent how much the stock

trades (il titolo viene scambiato) and/or the price agreed upon (concordato) by a buyer and a seller.

- Buyer > Seller: the stock’s price will climb (sale il prezzo delle azioni)

- Buyer < Seller: the price will drop (diminuisce il prezzo delle azioni

Question about a stock price:

Is this the correct price? -- Is it over valued or undervalued? --- Will the company grow? ---ACCOUNTING

Managers (internal decision makers) need information about the company’s business activities to manage

the operating, investing, and financing activities of the firm. Stockholders and creditors (external decision

makers) need information about these same business activities to assess whether the company will be able

to pay back its debts with interest and pay dividends.

= All businesses must have an accounting system that collects and processes financial information about an

organization’s business activities and reports that information to decision makers.

Accounting: is a system that collects and processes (analyzes, measures, and records) financial information

about an organization and reports that information to decision makers.

Types of accounting:

1) Financial Accounting

Financial accounting reports (periodic financial statements and related disclosures) provided to external

decision makers (creditors and investors) who evaluate the company

Output: Financial statements

Users: Investors, Shareholders, Creditors

Structure: Regulated, Regimented

2) Managerial Accounting

Managerial accounting reports (detailed plans and continuous performance reports) provided to internal

decision makers (managers) who run the company.

Output: Budgets, Cost Reports, Variance Reports, Ad-hoc Analyses

Users: Management

Structure: Loose, Flexible

What Types of Decisions do Financial Statements Help Investors and Creditors Make?

1. What are the likely Future Cash Flows?

2. What is the firm’s Value?

3. Are there any Red Flags that are a cause of concern?

4. What are the Risks and Uncertainties that are present or likely to arise?

5. What is the likelihood that the company will generate enough cash to Repay a Loan on a timely basis?

6. How well is Management performing?

7. Is the New Strategy working?

8. Does the company have enough Resources to expand?

Accrual Accounting and Estimates

When preparing consolidated financial statements according to Generally Accepted Accounting Rules

(GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) we use estimates and assumptions, because we

don’t have always the right numbers.

These affect our reporting amounts of assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses, as well as related

disclosures of contingent assets and liabilities

In some cases, we could reasonably have used different accounting policies and estimates. In some cases,

changes in the accounting estimates are reasonably likely to occur (è rotabile che si verifichino) from period

to period.

Accordingly, actual results could differ materially from our estimates.

Practically people can simply manipulate financial assumption, but this is not legal.

Basic concepts

Assumption (presupposto)

Separate entity assumption = states that business transactions are separate from the transactions of

the owners.

Going concern assumption (continuity assumption) = States that businesses are assumed to continue

to operate into the foreseeable future

Monetary unit assumption = States that accounting information should be measured and reported

in the national monetary unit without any adjustment for changes in purchasing power.

THE FOUR BASIC FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

The four basic financial statements are prepared by profit-making organizations for use by investors,

creditors, and other external decision makers. Those can be prepared at any point in time (such as the end

of the year, quarter, or month) and can apply to any time span (such as one year, one quarter, or one month).

Like most companies, these are prepared for external users (investors and creditors) at the end of each

quarter (known as quarterly reports) and at the end of the year (known as annual reports).

1. The Balance Sheet (bilancio): reports the financial position (amount of assets, liabilities and Stockholders’

equity) of an entity at a point in time (for example 31/12/2020). Snapchat of a precious situations. \

2. The Income Statement (conto economico): reports the revenues, expenses, and net income. More

specifically it reports revenues less the expenses of an entity for an accounting period (a quarter, a year).

It is how a company performe, it is the difference between revenues and costs.

3. The Cash Flow Statement (rendiconto finanziario): reports the cash inflows and outflows of an entity

during an accounting period in the categories of operating activities, investing activities, and financing

activities for an accounting period (a quarter, a year). It shows the change of cash in a year.

4. The Statement Of Shareholders’ Equity (prospetto di patrimonio netto): contains the Statement of

Retained Earnings which shows the amount of net income that the entity chose to retain in the business

and the amount it elected to pay out as dividends; shows changes in the equity accounts. It shows how

the equity change, and this means that this is the difference between total assets and total liabilities.

THE BALANCE SHEET

The balance sheet has the purpose of reporting the financial position (assets, liabilities and stockholders’

equity) of an accounting entity at a particular point of time.

Accounting entity: the organization for which financial data are to be collected.

The basic accounting equation (balance sheet equation)

Assets: economic resource that a company

has.

Liabilities (debiti) and Stockholders’ equity

(azioni): how the company finance these

resources

Perché sono importanti Asset, liabilities and stockholders?

- Asset: fanno capire se la compagnia ha risorse sufficienti per operare. Per capire nel caso in cui l’azienda

fallisca quanti asset possono essere venduti per ricavare denaro per i creditori.

- Liabilities: per capire se ci siano abbastanza risorse per pagare i debiti e per le banche per prestare soldi

alla compagnia.

- Stockholders: importante per la banca perché le richiesti dei creditori sono più importati di quelle dei soci.

Se l’azienda fallisce i suoi asset sono venduti e vengono pagati per primi i creditori e poi gli stockholders.

ASSETS (patrimonio)

They are the economic resource that a company has. Assets are probable future economic benefits owned

or controlled by an entity as a result of past transactions or events.

An asset must satisfy all the following:

It has a probable future economic benefit that can be reliably measured or estimated.

The firm controls (owns) it.

Its acquisition (ownership) is based on a current or past transaction or event.

How are Assets carried on the books?

Market value: it is the projected value of an asset in the market and it indicates its profitability. The value

is determined by the market participation. (Valore di mercato del prodotto, ipotizzato per capire i

probabili profitti)

Historical cost: it is the price paid for an asset when it was purchased. (Prezzo effettivo di vendita)

Order of presentation

Current Assets: Cash; Marketable Securities (or Investments); Accounts Receivable (A/R) = crediti verso

clienti): sales of an account, for ex you buy a computer and you pay it month for month this is the future

value that the company will obtain; Inventories (inventario) = a complete list of items that the company

have to sell hat is considered a current asset regardless of the time needed to produce and sell it; Prepaid

Expenses.

Assets that will be used or turned into cash within one year.

Non-Current Assets: Machinery and Equipment; Buildings; Land

Investments: Securities (Equity or Debt)

Intangibles: Patents; Copyrights; Brand Names; Deferred Charges; Goodwill

Ricorda: Every asset on the balance sheet is initially measured at the total cost incurred to acquire it. Balance

sheets do not generally show the amounts for which the assets could currently be sold. (Ogni attività in

bilancio è inizialmente valutata al costo totale sostenuto per acquisirla. I bilanci generalmente non mostrano

gli importi per i quali i beni potrebbero essere attualmente venduti)

LIABILITIES (passività)

They are the amount of financing provided by creditors (debts and obligations).

Probable future sacrifices of economic benefits arising from a present obligation to transfer cash, goods, or

services as a result of a past transaction. When you close the financial statement you have liabilities.

A liability must satisfy all the following:

It entails a probable future economic sacrifice that can be reliably measured or estimated.

The firm is obligated to pay it (that is, it “owns” the liability).

Its incurrence (“ownership”) is based on a current or past transaction or event.

Order of presentation: in order of maturity (how soon an obligation is to be paid).

Current liabilities: Accounts Payable to suppliers (A/P); Notes Payable (N/P); Expenses Payable; Deferred

revenue = advance payments a company receives for products or services that are to be delivered or

performed in the future; Short term Loans (debt), Current portion of long-term loan, Unearned Revenue

(for unredeemed gift cards that have been purchased by customers), Income Taxes Payable (owed to

federal, state, and local governments), and Accrued Expenses Payable (more specifically, Wages Payable

and Utilities Payable, although additional accrued liabilities may include Interest Payable, among others).

Short-term obligations that will be paid in cash (or other current assets) within the current operating

cycle or one year, whichever is longer.

Non-current liabilities: Long term Bonds and Loans (debt)

STOCKHOLDERS’ EQUITY (patrimonio azionisti; “attivo”) /SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY/ OWNERS’ EQUITY

Stockholders’ equity is the amount of financing provided to the company by its owners.

It is the residual claim on the firm’s assets, held by the firm’s stockholders.

If we rearrange the Accounting Identity: Equity = Assets – Liabilities.

Stockholders’ Equity is the:

Financing Provided by Owners is referred to as contributed capital

Financing Provided by Operations is referred to as earned capital or retained earnings.

Contributed capital (direct investment by the owners): when a company issue shares to the market any

proceeds from the sale go into “contributed capital”. It is the cash and other assets that shareholders

have given a company in exchange for stock. (Contante dato in cambio di azioni, conferimenti in denaro).

Generally, the contributed capital is characterized by two components:

Contributed capital = common stock + additional paid-in-capital

a) Common stock = is the par value of issued shares (is the investment of cash and other assets in the

business by the stockholders)

b) Additional paid-in capital = represents money paid by the shareholders of the company above the

par value of the company. The amount of contributed capital less the par value of the stock.

Contributed capital is raised by the company by selling stock in the market through the initial and

subsequent public offerings.

There is one type of events that cause the contributed capital accounts to change, and it is the buyback

of the shares by the company.

Qual’è la fonte (source) di common stock e additional paid-in-capital?

L'importo indicato in additional paid-in-capital e l'importo indicato in common stock: were raised by the

company by selling stock in the market through the initial and subsequent public offerings

(sono stati raccolti dall'azienda vendendo azioni sul mercato attraverso l'offerta pubblica iniziale e quella

successiva)

VEDI BENE CON LUDO TUTTO PARAGRAFO DELLA STOCKHOLDERS EQUITY

Earned capital/Retained earnings (indirect investment by the owners): is the amount of earnings (profits)

reinvested in the business (and thus not distributed to stockholders in the form of dividends) (Utili non

distribuiti o riserve). it is the accumulated earnings of the firm since its inception minus any dividends

declared to shareholders. (Sono gli utili ottenuti dopo aver sottratto gli eventuali dividendi da dare agli

azionisti).

𝑅𝑒𝑡𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑒𝑑 𝐸𝑎𝑟𝑛𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑠t = 𝑅𝑒𝑡𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑒𝑑 𝐸𝑎𝑟𝑛𝑖𝑛gst-1 + 𝑁𝑒𝑡 𝐼𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒t − 𝐷𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑑𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑠 𝐷𝑒𝑐𝑙𝑎𝑟𝑒𝑑t – Stock

Buybackst (or Share repurchasest).

> In this case there is a share buyback: every shareholder has a dividend which is taxed, the

shareholder can choose if he wants to partecipate in the buyback. The company thinks that the shares

are undervalued in the market. We have a share buyback because he company buy back its own shares

(azioni) from the market place because the company has cash on hand and the market is growing,

infact here the previous year we have more retained earnings than the current year because we use

that retained to buy back stock infact at the current year we have less retained earnings.

Question to think about:

- If the stock prices changes and it goes up by 15% what happen to equity? Nothing because when

the market prices stock changes nothing happens to the equity.

- Can retained earnings be negative? Yes if company loses money.

- Can Total Equity be negative? No, because it means that your assets are minor than your liabilities.

In this case the company will fail.

UBER: keep operating with negative equity, it do it because it see possible profit in the future so its

important to reach this goal.

Other Comprehensive Income (OCI) SONO GLI STESSI DELL’INCOME STATEMENT?

“BOOK VALUE OF EQUITY”

It the amount of cash remaining once a company's assets have been sold off and if existing liabilities were

paid down with the sale proceeds.

Book value of equity = total asset – total liabilities

WHAT BUSINESS ACTIVITIES CAUSE CHANGES IN FINANCIAL STATEMENT AMOUNTS?

Accounting focuses on certain events (external or internal) that have an economic impact on the company.

Those events are called transactions.

Transaction definition: (1) An exchange between a business and one or more external parties to a business

or (2) a measurable internal event such as the use of assets in operations.

How do transaction affect accounts?

Transaction effects increase and decrease assets, liabilities, and stockholders’ equity accounts (only

transactions affecting cash are reported on the statement).

To accumulate the dollar effect of transactions on each financial statement item, organizations use a

standardized format called an account.

Accounts definition: A standardized format that organizations use to accumulate the dollar effect of

transactions on each financial statement item.

Transaction analysis: the process of studying a transaction to determine its economic effect on the entity in

terms of the accounting equation (also known as the fundamental accounting model).

Assets (A) = Liabilities (L) + Stockholders’ Equity (SE), every transaction affects at least two accounts.

Example of dual effect of transaction:

For example if we purchase something we increase our assets but we have more liabilities (accounts

payable increase) because we do a promise to pay later

For example if we do a payment of cash to the suppliers we decreased our account liabilities because the

promise of payment is eliminated and we have cash decreased.

The direction of transaction effects

As we saw earlier in this chapter, transaction effects increase and decrease assets, liabilities, and

stockholders’ equity accounts. Each account is set up as a “T” with the following structure:

- Increases in asset accounts are on the left because assets are on the left side of the accounting equation

(A = L + SE).

- Increases in liability and stockholders’ equity accounts are on the right because they are on the right side

of the accounting equation (A = L + SE).

Ricorda:

o The term debit always refers to the left side of the T (account).

o The term credit always refers to the right side of the T (account).

Asset accounts increase on the left (debit) side and normally have debit balances.

It would be highly unusual for an asset account, such as Inventory, to have a negative (credit) balance.

Liability and stockholders’ equity accounts increase on the right (credit) side and normally have credit

balances.

How do companies keep track of account balances?

ACCOUNTING CYCLE = the process used by entities to analyze and record transactions, adjust the records

at the end of the period, prepare financial statements, and prepare the records for the next cycle.

Determine the impact of business transactions on the balance sheet using two basic tools: journal entries and

T-accounts:

Journal entries express the effects of a transaction on accounts in a debits-equal-credits format. The

accounts and amounts to be debited are listed first. Then the accounts and amounts to be credited

are listed below the debits and indented, resulting in debit amounts on the left and credit amounts

on the right. Each entry needs a reference (date, number, or letter).

T-accounts summarize the transaction effects for each account. These tools can be used to

determine balances and draw inferences about a company’s activities.

FINANCIAL RATIOS BASED ON THE BALANCE SHEET DA SISTEMARE TUTTO, SPIEGA A PAROLE

It is a quick way to obtain valuation; the best way to talk about ratios is to start with whatever is in the

denominator and say: “For every dollar of [denominator], there is XXX in the [numerator]”.

𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠

Example: 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 = 0.65 = for every dollar of assets that the company has, 65 cents has been funded by

liabilities.

Ratios (= rapporti fra due grandezze) are:

Liquidity

Current ratio measures the ability of the company to pay its short-term obligations with current assets.

Although a ratio above 1.0 indicates sufficient current assets to meet obligations when they come due,

many companies with sophisticated cash management systems have ratios below 1.0

𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠

Current Ratio = 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠

Current ratio measures the ability of the company to pay its short-term obligations with current assets.

o If Current Assets > Current Liabilities, then Ratio is greater than 1.0 -> a desirable situation to be in.

o If Current Assets = Current Liabilities, then Ratio is equal to 1.0 -> Current Assets are just enough to

pay down the short term obligations.

o If Current Assets < Current Liabilities, then Ratio is less than 1.0 -> a problem situation at hand as the

company does not have enough to pay for its short term obligations.

Example: if company C has $2.22 of Current Assets for each $1.0 of its liabilities; company C is more

liquid and is better positioned to pay off its liabilities.

Quick Ratio =

(𝑐𝑎𝑠ℎ 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑐𝑎𝑠ℎ 𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑠 + 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒𝑠)

𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠

The quick ratio is an indicator of a company’s short-term liquidity position and measures a company’s

ability to meet its short-term obligations with its most liquid assets. The higher the ratio result, the better

a company's liquidity and financial health; the lower the ratio, the more likely the company will struggle

with paying debts.

o A company having a quick ratio higher than 1 can instantly get rid of its current liabilities

o A result of 1 is considered to be the normal quick ratio. It indicates that the company is fully equipped

with exactly enough assets to be instantly liquidated to pay off its current liabilities.

o A company that has a quick ratio of less than 1 may not be able to fully pay off its current liabilities

in the short term.

Example: a quick ratio of 1.5 indicates that a company has $1.50 of liquid assets available to cover each

$1 of its current liabilities.

Debt (or Capital Structure Ratios)

The relative amount of debt used by a company is an indication of its financial risk. More debt means

that the company has more fixed finance charges (interest) that it must pay regardless of its profitability

(or lack thereof), raising the prospects of default and bankruptcy.

Debt-to-Assets Ratio =

𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠

𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠

“For every dollar of assets, the liabilities equal X, or about (X%) cents. Those to whom the company owes

money (the lenders, suppliers, employees, etc.) have provided (X%) cents in funding for every $1.00 of

assets”

Debt-to-Equity Ratio =

𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠

𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦

Growth Expectations (valore che esprime quanto l’azienda cresce sul mercato)

Market/Book Ratio =

𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑘𝑒𝑡 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦 (𝑜𝑟 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑘𝑒𝑡 𝐶𝑎𝑝)

𝑏𝑜𝑜𝑘 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦

Se il market value non ce l’hai, si trova facendo: Market Value = price * number of shares outstanding

WORKING CAPITAL (capitale circolante netto)

It is the dollar difference between total currents assets and total current liabilities.

The working capital accounts are actively managed to achieve a balance between a company’s short-term

obligations and the resources to satisfy those obligations. (Il capitale circolante è gestito per raggiungere

un equilibrio tra gli obblighi a breve termine e le risorse per soddisfarli).

A useful measure that indicates how much capital is used in day-to-day operations. It is a dollar amount.

It can be measured as either:

Option1: Working capital = 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 − 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠

Option 2: Working capital = 𝑐𝑎𝑠ℎ + 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 + 𝑖𝑛𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑜𝑟𝑦 − 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑝𝑎𝑦𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒

𝑤𝑜𝑟𝑘𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙

o You can also look at: 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 = “for every dollar in total asset the company has to give X dollar in

working capital”

Question:

- What is the optimal level of working Capital? It depends on the company.

- Can it be negative? Working capital could be negative, for example amazon has it beacuse it have a lot

of accounts payable (tanti debiti) and less cash.

The case of Dell Computers

INTERPRETING FINANCIAL RATIOS - Benchmarks

Two standard benchmarks:

1. The same company in previous periods

2. Companies in the industry in which the company operates

Caution:

The company itself could change from one period to the next.

The accounting estimates or principles being used could change

The comparison companies might have similar changes.

LIMITATIONS OF RATIOS

𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠

40,000

1) Example: Current Ratio = 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠 = 20,000 = 2.0

How do you read this ratio? -----Is the company liquid? Not necessarily because it could be inventory if it is not liquid.

2) Example: Quick Ratio =

(𝑐𝑎𝑠ℎ 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑐𝑎𝑠ℎ 𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑠 + 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒𝑠)

𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑠

20,000

= 20,000 = 1.0

How do you read this ratio? ---Is the company liquid? Not necessarily, beacause we don’t know what happens is going on with the

company

What is the conclusion from this? -----

Ratios can be manipulated

3) Example:

Current Assets = 250.0

Current Liabilities = 200.0

Current Ratio = 1.25

Loan Covenant: Company must maintain a Current Ratio of at least 1.30

To achieve the required ratio, the company pays its supplier 75 in cash.

Cash decreases by 75 and Accounts Payable decreases by 75.

Current Assets = 175.0

Current Liabilities = 125.0

Current Ratio = 1.40

Week 2 - 26 September 2022

THE INCOME STATEMENT

If the Balance Sheet is a “snapshot” of the firm at a given date, the Income Statement is a description of

the performance of the firm throughout the accounting period (a quarter, a year). It reports the revenues

less the expenses of the accounting period.

The elements of the Income Statement:

REVENUES (Revenues = Expenses + Net Income)

Revenues represent the amount that come from the sale of goods or service to customers.

Revenues represent an increase in assets or settlements of liabilities from the major or central ongoing

operations of the business.

They can be divided into:

Operating revenues = are the revenue generated from the major or regular ongoing operations of the

business. They result from the sale of goods

Non-operating revenues = are the additional revenue generated through other activities like rent,

dividends, etc..

Revenue sources

Many companies generate revenues from a variety of sources (regular operations of the business and nonoperating sources) for example:

- When Chipotle sells burritos to consumers, it has earned/obtain revenue. When revenue is earned,

assets (usually la voce: Cash or Accounts Receivable) often increase.

- Sometimes if a customer pays for goods or services in advance, often with a gift card, a liability account,

(usually la voce: Unearned or Deferred Revenue) is created.

At this point, no revenue has been earned/obtained, because it is in the form of an obligation so we can

define it as a liability. There is simply a receipt of cash in exchange for a promise to provide a good or

service in the future. When the company provides (= fornisce) the promised goods or services to the

customer, then the revenue is recognized, and the liability is eliminated.

Revenue Recognition Criteria/conditions:

a) Revenue should be recognized only when it is EARNED: so, when exists credible evidence of an

arrangement (the seller’s price is fixed or determinable, the customer pays or promises to pay) or the

earnings process is complete or almost complete (the company has met its contractual obligations and

is entitled to the revenue, delivery has occurred or services have been rendered)

b) Revenues must be REALIZED or REALIZABLE: collectability is reasonably assured.

To sum up: when revenue is earned, assets, usually Cash or Accounts Receivable, often increase. Sometimes

if a customer pays for goods or services in advance, often with a gift card, a liability account, usually

Unearned (or Deferred) Revenue, is created. At this point, no revenue has been earned because there is

simply a receipt of cash in exchange for a promise to provide a good or service in the future and when the

company provides the promised goods or services to the customer, then the revenue is recognized and the

liability is eliminated.

Cash is received before the goods or services are delivered. Until the goods or service is not delivered,

they record no revenue. Instead, it creates a liability account (Unearned Revenue) representing the

amount of good or service owed to the customers. Later, when customers redeem their gift cards and

the company deliver good or service, it earns and records the revenue while reducing the liability account

because it has satisfied its promise to deliver.

Cash is received in the same period as the goods or services are delivered. This depend on the sector,

for example in the restaurant industry it is possible in a few minutes.

Cash is received after the goods or services are delivered. When a business sells goods or services on

account, the revenue is earned when the goods or services are delivered, not when cash is received at a

later date.

Example: When would revenues be recognized in these cases?

1. Case: sale of a gift card by a retailer = revenue is recognized at the time the card is used

2. Case: sale of a non-refundable airline ticket = revenue is recognized just after the flight occurred

3. Case: sale of a rug with a right to return = revenue is recognized at the time of the sale along with an

allowance account for the case of return

4. Case: sale of a computer for $1,500 which includes a two-year service contract if repairs are necessary

(value of the contract is $ 240) = revenue for the computer is recognized at the time of sale. Revenue

for the service contract is recognized over the two year-period, probably monthly.

5. Case: sale of a gym membership for which you pay $3,600 upfront (the regular cost would have been

$4,500 if you didn’t pay upfront); you can use the gym anytime you want for 3 years and cancel

anytime during the 3 years and get the remaining money back. You decide to cancel after 4 months

of usage = at the time of the transaction a “deferred revenue” or “unearned revenue” account for

$3600 is created. For the 4 months revenue is recognized monthly. Once the membership is

cancelled, the cash is returned, and the deferred revenue account is removed.

Potential Issues with Revenue Recognition

Companies are under pressure to show revenue that meets expectations of market participants, this can

lead to:

1. Improper timing of revenue recognition

2. Fictitious revenue

3. Channel stuffing (Example: Coca-Cola)

Some Recent Reporting Scandals

SEC found that Fiat Chrysler inflated monthly sales results by paying automobile dealers to report fake

vehicle sales and maintaining a “cookie jar” of actual but unreported sales [INFLATED REVENUE]

SEC found that Nissan and its former CEO falsified financial reports (e.g., omitted $140 million to be paid

to the CEO in retirement) [UNDESTATED EXPENSES]

SEC is investigating iQIYI, a China-based video-streaming company, of committing fraud by

manufacturing orders and hiding expenses, which together added $1.9 billion to net income, 44% of the

reported amount [INFLATED REVENUES AND UNDESTAND EXPENSES]

A study discovers that around 20% of companies use accounting ruses to report earnings that don’t fully

reflect the companies underlying operations.

Earnings Management

Do Managers Manage Earnings to Meet or Beat Earnings Estimates and Benchmarks?

A study said that managers manage earnings to meet or beat analyst expectations

Another study said that managers communicate with analysts to manage expectations

Recent studies find that managers can manage earnings all the way up to the last moments before

an earnings announcement, following individual analyst forecasts and not just the consensus

How do Managers Manage Earnings?

Through managements’ discretion on accruals

Where can management employ discretion?

o Deferring revenue when not necessary

o Capitalizing expenses instead of recognizing them on the income statement

But managers can also use “real” earnings management (actions that affect real aspects of firms'

operations):

o Overproduction to report lower cost of goods

o Reducing prices to increase sale figures

A real impact of Earnings Management

Researchers have found links between earnings management to meet or beat expectations and

employee safety: They found one in 24 workers was hurt in outfits that either just beat or satisfied

earnings expectations versus one in 27 workers in outfits that comfortably beat or outright failed to meet

earnings expectations

These results, said the researchers, suggest that when managers are facing the possibility of narrowly

missing analyst forecasts, they might be increasing employee workloads, compelling them to move at a

faster pace, work longer hours and/or discount safety protocols that otherwise slow down work.”

Impact of Revenues on the Financial Statement

- On the Income Statement, revenues appear on the top line as “Revenues” or “Sales”.

- On the Balance Sheet, revenues impact Owners’ Equity. Specifically, Net Income affects Retained

Earnings, when Revenues increase so does Retained Earnings.

- On the Cash Flow Statement, revenues may affect Cash Flow from Operating Activities if cash is

received.

Example: Recording revenue

The Ace Consulting Firm sold $10,000 worth of consulting services to Hi-Tech Corp.

Ace is earning revenue. How does it record this in each of the following cases?

A. If Hi-Tech Corp pays Ace cash at the time the services are performed, how is it recorded?

Cash will go up by $10,000, this is an asset on the Balance Sheet. Revenues will go up by $10,000, this

is an item on the Income Statement that will impact Retained Earnings on the Balance Sheet

B. If Hi-Tech Corp pays Ace before the services are performed, how is it recorded?

Cash will go up by $10,000, this is an asset on the Balance Sheet. Unearned Revenues will go up

by $10,000, this is a liability on the Balance Sheet. Once services are performed the liability will

be cancelled and revenue will be recognized on the Income Statement.

C. If Hi-Tech Corp pays Ace after the services are performed, how is this recorded?

At the time service are performed Accounts Receivable will increase by $10,000, this is an asset

on the Balance Sheet. Revenues will increase by $10,000. At time of payment, cash will increase

by $10,000 and Accounts Receivable will decrease by the same amount.

EXPENSES

Expenses represent the amount of resources the entity used to earn revenues during the period. Expenses

reported in one accounting period actually may be paid for in another accounting period. Some expenses

require the payment of cash immediately, while others require payment at a later date. Some also may

require the use of another resource, such as an inventory item, which may have been paid for in a prior

period. Therefore, not all cash expenditures (outflows) are expenses, but expenses are necessary to generate

revenues.

Expense Recognition

Also called the matching principle: it requires that expenses be recorded in the same time period when

incurred in earning revenue.

Expenses generally fall into two categories:

1. Periodic

- Not tied to a particular revenue stream

- Paid after the service is rendered or the goods are received

2. Deferred (referred to as “Deferred Costs”, not “Deferred Expenses”)

- Associated with an identifiable revenue stream

- Paid before the identifiable revenue is received

Cash is paid before the expense is incurred to generate revenue. Companies purchase many assets that

are used to generate revenues in future periods. Examples include buying insurance for future coverage,

paying rent for future use of space, and acquiring supplies and equipment for future use. When revenues

are generated in the future, the company records an expense for the portion of the cost of the assets

used—costs are matched with the benefits.

Cash is paid in the same period as the expense is incurred to generate revenue. Expenses are sometimes

incurred and paid for in the period in which they arise. An expense is incurred and recorded (Repairs

Expense).

Cash is paid after the cost is incurred to generate revenue. Although rent and supplies are typically

purchased before they are used, many costs are paid after goods or services have been received and

used. Examples include using electric and gas utilities in the current period that are not paid for until the

following period, using borrowed funds and incurring Interest Expense to be paid in the future, and owing

wages to employees who worked in the current period. Any amount that is then owed to employees at

the end of the current period is recorded as a liability called Wages Payable (an accrued expense

obligation).

Expense Sources

Expenses can come from the main operations of the business (OPERATING EXPENSES):

o Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) = not really an expense per se; it is a cost

o Selling, General and Administrative Expenses (SG&A)

o Marketing Expenses (if separate from SG&A)

o Depreciation Expense

o Restructuring Expense

Expenses can come from non-operating sources (NON-OPERATING EXPENSES)

Impact of Expenses on the Financial Statement

On the Income Statement, expenses appear as COGS, Operating Expenses, or Non-operating Expenses

On the Balance Sheet, expenses impact Owners’ Equity. Specifically, through Net Income which is related

to the Retained Earnings account. Every time an expense is recognized, Retained Earnings decreases.

On the Cash Flow Statement, expenses may affect Cash Flow from Operating Activities if cash is paid out.

Example: Recording expenses

The Ace Consulting Firm sold $10,000 worth of consulting service to Hi-Tech Corp.

Hi-Tech is incurring an expense. How does it record this in each of the following cases?

A. If Hi-Tech Corp pays Ace cash at the time the services are performed, how is it recorded?

An expense will be recognized of $10,00D, this will appear on the Income Statement and reduce

Net Income. Cash will go down by $10,000

B. If Hi-Tech Corp pays Ace before the services are performed, how is it recorded?

An asset "Prepaid Expenses" will be created on the Balance Sheet. Cash will go down by $10,000

C. If Hi-Tech Corp pays Ace after the services are performed, how is this recorded?

An expense will be recognized of $10,000; this will appear on the Income Statement and reduce

Net Income. A liability named *Accrued Expenses Payable" will be created, once the expense is

paid it will be removed

NET INCOME (net earnings) (Net Income = total revenues – total expenses)

Net Income often called “the bottom line” represent the excess of total revenues over total expenses. If

total expenses exceed total revenues, a net loss is reported. Net income normally does not equal the net

cash generated by operations.

Income tax expenses= it is the pre-tax income; it is income that we have before of subtracting tax

Operating Income = represents a measure of the profit from central ongoing operations.

Operating income = net sales (operating revenues) – operating expenses (including cost of goods sold).

ACCRUAL ACCOUNTING AND THE INCOME STATEMENT

Accrual basis accounting: records revenues when earned and expenses when incurred, regardless of the

timing of cash receipts or payments.

Why do we use accrual accounting rather than cash accounting? Because it provides the best economic

picture of the company, it shows the relationship between Revenues and Net Income

Example: Suppose company A sells $1,000,000 of goods to Company B and delivers them.

The goods cost Company A $900,000 (which it has paid). Company B will pay Company A within 3 weeks.

What will happen?

Cash accounting

Revenue

Cost

Net Income

Profit Margin:

Net Income/Revenues

$

0

- 900,000

= 900,000

Not meaningful

Accrual accounting

Revenue

Cost

Net Income

Profit Margin:

Net Income/Revenues

$

1,000,000

- 900,000

= 100,000

0.1

The two basic accounting principles

The two basic accounting principles that determine when revenues and expenses are recorded under accrual

basis accounting are:

- the revenue recognition principle = revenues are recognized (1) when the company transfers promised

goods or services to customers (2) in the amount it expects to be entitled to receive.

- the expense recognition principle (also called the matching principle) = requires that expenses be

recorded in the same time period when incurred in earning revenue.

The Income Statement – Kroger (come la Conad in Italia)

The top line in the income statement is Sales (also referred to as “Revenue”). This is the main source of

income from the continuing operations of the firm. Firms can present revenues from different activities

or just in one line (as seen by Kroger).

Revenues are followed by the “Cost of Goods Sold” (COGS), these are the costs immediately associated

with the sales. These mainly include the cost of inventory but also include any other cost management

deems appropriate.

= The difference between the two is called the “Gross Profit”

“THE GROSS PROFIT” (Utile Lordo) SCRIVI TYUTTE LE FORMULE

Gross profit = is a measure of the firm's profitability from the sale of its products.

Gross profit is the total revenue less only those expenses directly related to the production of goods for

sale, called the cost of goods sold (COGS). COGS represents direct labor, direct materials or raw materials,

and a portion of manufacturing overhead that's tied to the production facility. COGS does not include

indirect expenses, such as the cost of the corporate office.

Below the Gross Profit the firm presents other operating items such as:

o Selling General and Administrative (SG&A) expenses – these can include wages and advertising costs

o Depreciation and amortization – associated with fixed assets.

Gross Profit = total revenues – total expenses (including cost of goods)

𝐺𝑟𝑜𝑠𝑠 𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡

Gross Profit Margin (Gross Margin ratio) = 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒 o

𝑆𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 − 𝐶𝑂𝐺𝑆

𝑆𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠

Since COGS represents the cost of acquiring inventory and manufacturing the products, gross profit reflects

the revenue left over to fund the business after accounting for the costs of production.

It doesn’t include debt expenses or taxes.

“THE OPERATING PROFIT”

Operating Profit = Subtracting these expenses from Gross Profit produces the “Operating Profit” which

represents the income to the firm from its continuing operations.

Derived from gross profit, operating profit reflects the residual income that remains after accounting for all

the costs of doing business. In addition to COGS, this includes fixed-cost expenses such as rent and

insurance, variable expenses, such as shipping and freight, payroll and utilities, as well

as amortization and depreciation of assets. All the expenses that are necessary to keep the business

running must be included.

“Operating Profit” is also referred to as “the line”; items “Below the Line” (under Operating Profit):

• Interest expense (or income)

• Gain (or loss) on investments

• Gain (or loss) on the sale of business

Operating Profit Margin:

𝑂𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑓𝑖𝑡

𝑆𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠

Ricorda: Operating profit c’è scritto gia, devo trovare l’Operating profit Margin io

“EARNINGS BEFORE TAX (EBT)”

Earnings before tax = Subtracting (or adding) these items to Operating Profit leads to Earnings Before Tax.

“NET INCOME”

Net Income = Subtracting the Tax Expense from EBT leads to Net Income. “Net Income” is also referred to

as “the bottom line”. It is different from the gross profit because in net income I subtract the taxes.

OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME

Accounting rules and regulations require some gains and losses be presented apart from the income

statement. Some examples:

Changes in revaluation surplus (IAS 16 and IAS 38)

Actuarial gains and losses on defined benefit plans recognized in accordance with IAS 19

Gains and losses arising from translating the financial statements of a foreign operation (IAS 21)

Gains and losses on re-measuring available-for-sale financial assets (IAS 39)

The effective portion of gains and losses on hedging instruments in a cash flow hedge (IAS 39).

REVIEW

1. What transactions do the following reflect? What was the transaction that preceded them (if any)?

a. Salaries Payable decreases by $75,000; Cash Decreases by $75,000

> Salary Expense increases by $75,000; Salaries Payable increases by $75,000

It describes the workers paid, workers worked and provided services which generated revenue for

the company, the income statement before this would be lower but they would have liabilities in the

balance sheet; salaries expenses increase by 75.000 and salaries payable increases by 75.000.

b. Cash increases by $35,000; Interest Receivable decreases by $35,000

> Interest Receivable increases by $35,000; Interest Revenue increases by $35,000

We are owed interest but they still haven’t paid us; interests receivable increases by 35.000 and

interest revenue increases by 35.000.

c. Utility Expense increases by $45,000; Utilities Payable increases by $45,000

> No preceding transaction

d. Unearned Revenue decreases by $50,000; Revenue increases by $50,000

> Cash increases by $50,000; Unearned Revenue increases by $50,000

The company gets the cash ut the good has not been delivered so it is a current liability; cash

increases by 50.000 and unearned revenue increases by 50.000.

e. Depreciation Expense increases by $10,000; Accumulated Depreciation increases by $ 10,000

> Purchase of fixed asset would have been recorded

Accrual accounting system allows o avoid recognizing the huge investments at once dividing the

expenses in the period of the assets; purchase of fixed asset would have been recorded

2. Why does accrual accounting require depreciation of plant and equipment?

Matching Principle

To sum up:

If I had the revenues and I subtract only the COGS expenses I have the Gross Profit that measure

profitability from its production.

If I had the revenues and I subtract COGS expenses, fixed and variable expenses, amortization and

deprecation of assets.

At the end I have the Net income that is the operating income less the taxes.

TRANSACTION ANALYSIS RULES

All accounts can increase or decrease, although revenues and expenses tend to increase throughout a

period. For accounts on the left side of the accounting equation, the increase symbol + is written on the left

side of the T-account. For accounts on the right side of the accounting equation, the increase symbol + is

written on the right side of the T-account, except for expenses, which increase on the left side of the Taccount. That is because, as expenses increase, they have an opposite effect on net income, the Retained

Earnings account (which increases on the credit side), and thus Stockholders’ Equity.

Debits (dr) are written on the left of each T-account and credits (cr) are written on the right.

Every transaction affects at least two accounts.

When a revenue or expense is recorded, either an asset or a liability will be affected as well:

Revenues increase stockholders’ equity through the account Retained Earnings and therefore have credit

balances (the positive side of Retained Earnings). Recording revenue requires either increasing an asset

(such as Accounts Receivable when selling goods on account to customers) or decreasing a liability (such

as Unearned Revenue that was recorded in the past when cash was received from customers before

being earned).

Expenses decrease stockholders’ equity through Retained Earnings. As expenses increase, they have the

opposite effect on net income, which affects Retained Earnings. Therefore, they have debit balances

(opposite of the positive credit side in Retained Earnings). That is, to increase an expense, you debit it,

thereby decreasing net income and Retained Earnings. Recording an expense requires either decreasing

an asset (such as Supplies when used) or increasing a liability (such as Wages Payable when money is

owed to employees).

When revenues exceed expenses, the company reports net income, increasing Retained Earnings and

stockholders’ equity.

When expenses exceed revenues, a net loss results that decreases Retained Earnings and thus

stockholders’ equity

ADJUSTMENTS

Managers are responsible for preparing financial statements that will be useful to investors, creditors, and others or

analyzing the past and predicting the future.

Revenues are recorded when earned

Expenses are recorded when incurred to generate revenue

Assets are reported at amounts that represent the probable future benefits remaining at the end of

the period

Liabilities are reported at amounts that represent the probable future sacrifices of assets or

services owed at the end of the period.

Because recording these and similar activities daily is often very costly, most companies wait until the end

of the period (annually, but monthly and quarterly as well) to make adjustments.

Adjusting entries are necessary at the end of the accounting period to measure income properly, correct

errors, and provide for adequate valuation of balance sheet accounts.

Type of Adjustments

1. Deferred Revenues: When a customer pays for goods or services before the company delivers them,

the company records the amount of cash received in a deferred (unearned) revenue account. This

unearned revenue is a liability representing the company’s promise to perform or deliver the goods or

services in the future. Recognition of (recording) the revenue is postponed (deferred) until the

company meets its obligation.

2. Accrued Revenues: Sometimes companies perform services or provide goods (that is, earn revenue)

before customers pay. Because the cash that is owed for these goods and services has not yet been

received and the customers have not yet been billed, the revenue that was earned may not have been

recorded. Revenues that have been earned but have not yet been recorded at the end of the

accounting period are called accrued revenues.

3. Deferred Expenses: Assets represent resources with probable future benefits to the company. Many

assets are used over time to generate revenues, including supplies, buildings, equipment, and prepaid

expenses for insurance, advertising, and rent. These assets are deferred expenses (that is, recording

the expenses for using these assets is deferred to the future). At the end of every period, an

adjustment must be made to record the amount of the asset that was used during the period.

4. Accrued Expenses: Numerous expenses are incurred in the current period without being paid until the

next period. Common examples include Wages Expense for the wages owed to employees who worked

during the period, Interest Expense incurred on debt owed during the period, and Utilities Expense for

the water, gas, and electricity used during the period. These accrued expenses accumulate (accrue)

over time but are not recognized as expenses with the related liability until the end of the period

through an adjusting entry.

Ricorda:.Recording adjusting entries has no effect on the Cash account (almost every account, except Cash,

could require an adjustment)

Week 2 - 30 September 2022

DEBITING AND CREDITING CHE CENTRA? GIA MESSA QUESTA FOTO SOPRA

Journal Entries:

General format: Account being Debited XXXX

Account being Credited XXXX

Examples: of Journal Entries that involve Balance Sheet Accounts CHE CENTRA?

MEASURING AND REPORTING RECEIVABLES

Receivables may be classified in three common ways:

1. Account receivable or note receivable

Accounts receivable (trade receivables/receivables) = is created by a credit sale on an open account

Notes receivable = is a promise in writing ( a formal document) to pay (1)a specified amount of money,

called the principal, at a definite future date known as the maturity date and (2) a specified amount

of interest at one or more future dates. The interest is the amount charged for use of the principal.

2. Trade receivable or nontrade receivable

Trade receivable = is created in the normal course of business when a sale of merchandise or services

on credit occurs

Nontrade receivable = arises from transactions other than the normal sale of merchandise or services.

3. Current receivable or noncurrent receivable

Current receivable = short-term

Noncurrent receivable = long term

ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Accounts Receivable are commitments of customers to pay arising from past sales.

These are basically sales on credit.

Granting credit to customers is costly to the seller for two reasons:

1. Credit risk (bad debt = debt that won’t be repaid)

2. Cost of capital (seller receives the cash only at some future date; money received today is worth more

than money received tomorrow/ time value of money).

Issues Regarding Accounts Receivable

How should Accounts Receivable be valued? How should the Bad Debt Expense be determined?

1. Direct write-off method

A receivable is written-off only after the account is determined to be uncollectible. What are some

potential problems with this?

2. Allowance method

An estimate is made of the expected uncollectible accounts out of all the credit sales for a period. The

estimate is recorded as an expense in the period the credit sales are made.

There are two approaches that can be taken:

a) Aging method

b) Percentage of Sales

Two Allowance Methods

The difference is that:

1. Aging-of-Accounts – Focus is on the Balance Sheet

2. Percentage of Sales – Focus is on the Income Statement

Applying the Allowance Method:

Consider the following three stages in the process:

1. At the end of the initial year, establish an allowance by estimating future uncollectible accounts.

2. During the subsequent year, write off actual bad debts as uncollectible. Note that actual write-offs may

differ from the previous year’s estimate.

3. At the end of the subsequent year, once again estimate future uncollectible accounts and replenish the

allowance.

Comparison of the Aging-of-Accounts vs the Percentage-of-Sales Methods

Aging-of-Accounts = results in a more accurate valuation of the Accounts Receivable on the Balance

Sheet Does not provide good matching with revenues in the income statement.

Percentage-of-Sales Method = results in better matching of Revenues with the Bad Debt Expense

Directly compute the amount to be recorded as Bad Debt Expense on the income statement for the

period in the adjusting journal entry but it does not do a good job of valuing Accounts Receivable on the

Balance Sheet.

EXAMPLE 1:

A business is established at the beginning of Year 1.

During Year 1:

Sales (all on credit) = $1,000,000

Accounts Receivable at the end of the year = $170,000

No account that has become uncollectible has been discovered.

During Year 2:

Sales (all on credit) = $2,000,000

An account with a balance of $1,700 is deemed uncollectible.

Accounts Receivable at the end of the year = $170,000

Balance of accounts receivable at the end of Year 1 by age

Using the Aging Method

To reflect the expected uncollectible amount of $2,650 the company must recognize an expense on the

Income Statement (as part of SG&A).

To balance this expense out the company creates a Balance Sheet account called “Allowance for Doubtful

Accounts” of the same amount. This is a “Contra Asset” account (it is an asset account, but it reduces

assets).

Ricorda: The Bad Debt Expense is the cost of estimated future bad debts arising from Sales in the current

period.

Bad debt expense

Expense is the cost of estimated future bad

debts arising from Sales in the current

period.

It is the expense associated with estimated

uncollectible accounts receivable.

The Bad Debt Expense is included in the

category “General and Administrative”

expenses on the income statement.

It decreases net income and stockholders’ equity.

Accounts Receivable could not be credited in the journal entry because there is no way to know which

customers’ accounts receivable are involved. So the credit is made, instead, to a contra-asset account called

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts, this reduce the book value and the total asset.

During Year 2

An uncollectible account in the amount of $1,700 is discovered and deemed uncollectible

To write-off the bad debt: the company will reduce the allowance and reduce the Accounts Receivable

account (note that the AR that appears on the Balance Sheet is the amount NET of any allowance).

Write off impact on Balance Sheet:

At the end of Year 2

The company needs to have $4,200 in the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts.

Currently, there is $950 in the Allowance [$2,500 – 1,700 (write-off) = 950]

There needs to be an additional $3,250 in the Allowance to bring the balance up to $4,200

Expected value

of uncollectible

accounts

The $3,250 “replenishes” the Allowance account and is recognized as an expense on the Income

Statement.

Using the Percentage-of-Sales Method

The Bad Debt Expense is computed each year as a pre-determined percentage multiplied by the Credit sales

for the year

Back to the Example

Year 1:

Recall that for Year 1, Credit Sales were $1,000,000

Suppose that the estimated percentage of bad debts is 0.25%

The estimated Bad Debt Expense for the year is: 2,500 (1,000,000 X 0.25%)

The company will create the Allowance in the same way as before, recognizing a bad debt expense for the

amount. The company will treat the write-off (1,700) in the same way.

Year 2:

Recall that for Year 2 Credit Sales were $2,000,000.

The estimated Bad Debt Expense for the year is: 5,000 (2,000,000 X 0.25%)

What will the company do?

Recognize a bad debt expense of 5,000, increasing the Allowance by the same amount

What is the balance of the Allowance account at the end of the year?

EXAMPLE 2:

Allowance for credit losses

Trade accounts receivable

arise from the sale of

products on trade credit

terms. On a quarterly basis,

we review all significant

accounts as to their past due

balances,

as

well

as

collectability

of

the

outstanding trade accounts

receivable for possible write off. It is our policy to write off the accounts receivable against the allowance

account when we deem the receivable to be uncollectible. Additionally, we review orders from dealers that

are significantly past due, and we ship product only when our ability to collect payment from our customer

for the new order is probable.

Our allowances for credit losses reflect our best estimate of losses inherent in the trade accounts receivable

balance. We determine the allowance based on known troubled accounts, weighing probabilities of future

conditions and expected outcomes, and other currently available evidence

Amount not collect at the end: beginning balance+bad debt expense (charged/(credited) to costs and

expensens)-Write off (deduction)

How much account receivables the company doesn’t collect? Schedule II valuation and qualifying

account (3406). A/R: BB+Sales on Account(acquisitions)-Collection on Account(Charged to cost and

expense)-Write offs (deduction)=EB

Bad debt = (Charged/Credited) to Costs and Expenses – Estimation of what won’t be collected

Write off = Deductions (no impact) – I’m sure I’m not collecting

Ending balance is going to be the beginning balance of next year: 7541 = 2180 (beginning of balance) +

13263 (bad debt) -7902 (write off)

Allowance for doubtful account: beginning allowance+bad debt expense=ending allowance

ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLES AND RATIOS

We want to be able to compare the company to itself over the years and to other companies based on their

efficiency in collecting receivables and managing their credit sales in general.

Helpful Ratios and Analyses:

1. Accounts Receivable as a % of Sales

2. Allowance for Doubtful Accounts / Accounts Receivable

3. Bad Debt Expense as a % of Sales

4. Compare the sum of write-offs with the sum of the Bad Debt Expense for two-three years (the

information for this is provided as part of the footnotes to the financial statements)

5. Determine how much cash was actually collected from customers during the year

6. Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio, that allows us to see how quickly the company collects its credit

sales (or how efficient they are in doing so)

a) Receivable turnover ratio: it reflects how many times average trade receivables were recorded and

collected during the period.

𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑛𝑢𝑒𝑠 (𝑜𝑟 𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠)

𝑅𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑡𝑢𝑟𝑛𝑜𝑣𝑒𝑟 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜 = 𝐴𝑣𝑎𝑟𝑎𝑔𝑒 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 = times receivable collected

Ricorda:

Average account receivable =

𝐵𝑒𝑔𝑖𝑛𝑛𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑒 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒+𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑑𝑒 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡𝑠 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒

2

Beginning or ending net trade account è la stessa cosa di account receivable gross, dunque

entrambi sono uguali a : A/R + net of allowance.

𝐴𝑅

Beginning; ending net account; account receivable gross = 𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒

If we have net of allowance we have to summarize it to A/R

If we have allowance we have to subtract it to A/R

b) Average days sales in receivables: it indicates the average time it takes a customer to pay its account.

365

AR turnover in days: receivable turnover ratio = Days to Collect Receivables of Days Sales Outstanding

(DSO)

If we know the AR turnover in days from the previous year, we can subtract the different AR turnover

during the years and if the result is negative, it seems that the company is getting worse in collecting

receivable.

1. Domanda: What % A/R does management not expect to be able to collect in 2020?

𝑁𝑒𝑡 𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒

1211

=

= 0,0514 -> 5.14%

(𝐴𝑅+𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒) (22340+1211)

2. Domanda: On average, how long did it takes for Basset to collects its receivables during 2020?

Remember that credit sales are 30% of Total revenues $385863

Credit sales: 30% of total revenues $385863 = 0.3 * 385863 = 115758

Average account receivable:

beginning net trade AR + ending net trade AR

2

=

(21378 + 815) + (22340 + 1211) / 2 = 22872

Receivable turnover ratio:

𝑁𝑒𝑡 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠 (𝑜𝑟 𝐶𝑟𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡 𝑠𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠)

𝐴𝑣𝑎𝑟𝑎𝑔𝑒 𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒

=

115758

22872

= 5.06

365

AR turnover in days: receivable turnover ratio = 365/ 5.06 = 72.1 days

AR turnover in days over the year: 72.1 days (2020) - 63 days (2019) - 54 days (2018) = - 45

So the company is getting worse in collecting receivable.

EFFECT ON STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS

When there is a net decrease in accounts receivable cash collected from customer is more than revenue,

and this decrease is added in computing cash flows.

When there is a net increase in account receivable cash collected from customers is less than revenue, and

this increase is subtracted in computing cash flows.

I can compare bad debt and write off to see if evaluate predictions in schedule II about the ending balance

are true.

If bad debt expenses are higher than write offs

Cash and cash equivalents

IAS 7 – Definition of Cash and Cash Equivalents

Cash is defined as cash on hand and any deposit with banks (think of your bank account)

Cash Equivalents is defined as short-term, highly liquid investments that are readily convertible into

known amounts of cash

o Subject to low risk (i.e., low chances of large changes in value over short periods of time)

o Held to meet short term obligations of the firm

o Maturity of instruments is three months or less

The change in the cash position of the firm is explained by the Cash Flow Statement (we will get to it later

in the course).

Restricted Cash

- These are sums of cash reserved for a specific purpose, usually specified by a contract.

- Restricted Cash is reported separately on the Balance Sheet and the Cash Flow Statement.

Week 3 - 3 October 2022

INVENTORY

Inventory definition = is tangible property that is (1) held for sale in the normal course of business or (2)

used to produce goods or services for sale. Inventory is reported on the balance sheet as a current asset

because it normally is used or converted into cash within one year or the next operating cycle.

The types of inventory normally held depend on the characteristics of the business:

Merchandisers business (wholesale or retail businesses) hold Merchandise inventory = goods (or

merchandise) held for resale in the normal course of business. The goods usually are acquired in a

finished condition and are ready for sale without further processing.

Example: For Harley-Davidson, merchandise inventory includes the Motorclothes line and the parts and

accessories it purchases for sale to its independent dealers.

Manufacturing business hold three type of inventory:

o Raw materials inventory: Items acquired for processing into finished goods. These items are

included in raw materials inventory until they are used, at which point they become part of

work in process inventory.

o Work in process inventory: Goods in the process of being manufactured but not yet complete.

When completed, work in process inventory becomes finished goods inventory.

o Finished goods inventory: Manufactured goods that are complete and ready for sale.

Issues regarding inventory:

1. What costs are included in inventory?

2. What information is provided about inventory in the financial statements?

3. LIFO and FIFO issues

4. How do you evaluate inventory management?

Required Disclosures on Inventory

Companies are required to disclose:

a) the inventory method(s) being used and

b) the balance of the inventory by stage (i.e., raw materials, work-in-process, finished goods).

Companies that use LIFO must also disclose:

a) the replacement cost of the inventory (this is approximately equal to the FIFO value) and

b) the difference between the LIFO value of the inventory and the inventory’s replacement cost. This is

known a the “LIFO Reserve.”

Example: LAZBOY

Inventories are stated at the

lower of cost or market. Cost is

determined using the last-in,

first-out ("LIFO") basis for

approximately 60% and 61% of

our inventories at April 30,

2022, and April 24, 2021,

respectively. Cost is determined

for all other inventories on a

first-in, first-out ("FIFO") basis.

The majority of our La-Z-Boy

Wholesale segment inventory

uses the LIFO method of

accounting, while the FIFO

method is used primarily in our

Retail segment and Joybird

business.

Purchase inventory:

Inventory XXXX (+A)

Cash or A/P XXXX (-A/+L)

Sell Inventory:

Cost of Goods Sold YYYY (+Ex,

-NI)

Inventory YYYY (-A)

Inventory: For our upholstery business within our Wholesale segment, we maintain raw materials and workin- process inventory at our manufacturing locations. Finished goods inventory is maintained at our nine

regional distribution centers as well as our manufacturing locations. Our regional distribution centers allow

us to streamline the warehousing and distribution processes for our La-Z-Boy Furniture Galleries® store

network, including both company-owned stores and independently-owned stores. Our regional distribution

centers also allow us to reduce the number of individual warehouses needed to supply our retail outlets and

help us reduce inventory levels at our manufacturing and retail locations.

Costs included in Inventory

What cost are included in inventory? Initial costs

What about fixed costs? Are they incorporated in the inventory value?

Example: In a month, a commercial tractor manufacturer had the following costs (all $ in 000):

- Total fixed costs $3,600

- The selling price per tractor is $110.

- Variable costs: $50/unit

Let’s examine three scenarios:

1. Sales = Production

2. Sales < Production

3. Sales << Production

Inventory and accounts payable from balance sheet and COGS from income statement. How to

understand how many units the company purchases. Beginning inventory (226,137) + purchases (x) –

COGS (1,440,042) = Ending Inventory (303,191), Purchase = 1,517,096

To see how much cash the company used for the purchase Beginning accounts payable (94,152) +

purchases (1,517,096) = Cash (y) and Ending accounts payable (104,025), Cash = 1,507,223

Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

Cost of goods sold (CGS) expense is directly related to sales revenue. Sales revenue during an accounting

period is the number of units sold multiplied by the sales price. Cost of goods sold is the same number of

units multiplied by their unit costs.

A company starts each accounting period with a stock of inventory called beginning inventory (BI). During

the accounting period, new purchases (P) are added to inventory. The sum of the two amounts is the

goods available for sale during that period. What remains unsold at the end of the period becomes ending

inventory (EI) on the balance sheet. The portion of goods available for sale that is sold becomes cost of

goods sold on the income statement. The equation is BI + P − EI = CGS.

LIFO AND FIFO

There are 2 inventory costing methods for determining cost of good sold. THE inventory costing methods

are alternative ways to assign the total dollar amount of goods available for sale between (1) ending

inventory and (2) cost of goods sold.

Lifo and Fifo assume that the inventory costs follow a certain flow.

A. FIFO

The first-in, first-out method, frequently called FIFO, assumes that the earliest goods purchased (the

first ones in) are the first goods sold, and the last goods purchased are left in ending inventory. This

means that each purchase is deposited from the top in sequence (i nuovi acquisti si trovano in cima).

Each good sold is then removed from the bottom in sequence (dal fondo vengono rimossi i primi beni

acquistati). THE FIRST IN IS FIRST OUT. The goods that are removed become cost of goods sold (CGS).

The remaining units become ending inventory. FIFO allocates the oldest unit costs to cost of goods sold

and the newest unit costs to ending inventory.

B. LIFO

The last-in, first-out method, often called LIFO, assumes that the most recently purchased goods (the

last ones in) are sold first and the oldest units are left in ending inventory. This means that each

purchase is deposited from the top in sequence (i nuovi acquisti si trovano in cima). But unlike FIFO,

each good is removed from the top in sequence (dalla cima vengono rimossi gli ultimi beni acquistati).

The goods that are removed become cost of goods sold (CGS). The remaining units become ending

inventory. LIFO allocates the newest unit costs to cost of goods sold and the oldest unit costs to ending

inventory.

Increase or Decrease:

An increase in the LIFO Reserve during the period means that the reported COGS is greater than it

would have been had FIFO been used. (if LIFO reserve increase, the COGS is greater than in FIFO

A decrease in the LIFO Reserve during the period means that the reported COGS is lower than it would

have been had FIFO been used. The decrease suggests that during the period, inventory costs were

declining, inventories were reduced (liquidated) or both.(if LIFO reserve decrease, the COGS is lower

than in FIFO)

Example:

For LAZYBOY we can notice that the LUFO Reserve (referred to as Excess of FIFO over LIFO) increase

form Apr.24,2021 to Apr. 30,2019.

Advantages and Disadvantages of LIFO vs. FIFO

1. Which method is linked to the physical flow of goods?

2. Which method provides better matching of revenues and costs on the Income Statement? In the case

of increasing costs is FIFO, and in the case of decreasing costs is LIFO.

3. Which method provides better valuation of inventory on the Balance Sheet? In the case of increasing

costs is FIFO, and in the case of decreasing costs is LIFO.

4. Which method results in lower taxes? In the case of increasing costs is LIFO, and in the case of

decreasing costs is FIFO.

Anyway, the choice of methods is normally made to minimize taxes, this means that we use the method

that result in lower taxes.

Explanation:

For inventory with increasing costs, LIFO is used on the tax return because it normally results in lower

income taxes. When unit costs are rising, LIFO produces lower net income and a lower inventory

valuation than FIFO.

For inventory with decreasing costs, FIFO is most often used for both the tax return and financial

statements. When unit costs are declining, LIFO produces higher net income and higher inventory

valuation than FIFO.

International Perspective

LIFO and International Comparisons

While U.S. GAAP allows companies to choose between FIFO and LIFO, International Financial Reporting

Standards (IFRS) currently prohibit the use of LIFO.

U.S. GAAP also allows different inventory accounting methods to be used for different types of inventory

items and even for the same item in different locations.

IFRS requires that the same method be used for all inventory items that have a similar nature and use.

These differences can create comparability problems when one attempts to compare companies across

international borders.

LOWER OF COST OR MARKET – Valuing Inventory on an Ongoing Basis

Example: GAP has 100,000 high quality sweatshirts in stock that cost $18 each. When the sweatshirts

were purchased, the intention was to sell these sweatshirts at $30 each. The sweatshirts were not a

best seller. In fact, consumers would only buy them if they were marked down by 60% to $12 per shirt.

Further, $3,000 in transportation costs would be incurred to move these shirts from retail stores to

factory outlets.

How does the LCM rule apply?

Starting from the concept that inventories should be measured initially at their purchase cost in

conformity with the cost principle, if value of inventory falls below original carrying cost: inventories

must be reported at the lower of cost or market. This method serves to recognize a loss when net

realizable value drops below cost.

“Market” = “net realizable value” (= estimated selling price of the inventory less any costs of

completion, disposal, transportation, etc).

Compare carrying value with net realizable value

Carrying cost of the inventory = $1,800,000 [100,000 X 18]

Net realizable value = $1,197,000 [(100,000 X 12) – 3,000]

Difference = $603,000

Under lower of cost or net realizable value, companies recognize a “holding” loss (perdita di

magazzino) in the period in which the net realizable value of an item drops (si riduce), rather than in

the period the item is sold. When the NRV of a certain number of goods is lower than their cost per

item we will have this effects on BS: the cost of sold is a debt (debito perchè mi costano di più di

quanto posso realizzare) that increase equity but decrease stockholders’ equity (+E,-SE) and instead of

the fact that some goods are sold we have a lower asset (-A) because inventory is reduced and a credit

that come from the sell of the goods. The effect on the IS is a reduction of the income because there is

an increase in cost (+C, -NI).

Is there a “higher of cost or market” (HCM) rule?

Companies are required to report the fall in inventory. What about inventory increases?

Suppose that the cost of the GAP sweatshirts did not fall. In fact, the new cost of sweatshirts (if GAP

decided to replenish the inventory) is $20 each. Further, because customers really like the sweatshirts,

GAP decided to increase the sales price of the 100,000 sweatshirts in stock to $32 each.

How would the financial statements reflect this?

BS: cost of goods sold -E;+SE, Inventory unaffected

IS: +R,+NI

INVENTORY: EFFECT ON STATEMENT OF CASH FLOW

When a net decrease in inventory for the period occurs, sales are greater than purchases; thus, the

decrease must be added in computing cash flows from operations.

When a net increase in inventory for the period occurs, sales are less than purchases; thus, the increase

must be subtracted in computing cash flows from operations.

When a net decrease in accounts payable for the period occurs, payments to suppliers are greater than

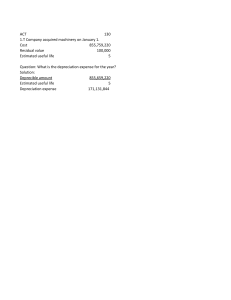

new purchases on account; the decrease must be subtracted in computing cash flows from operations.