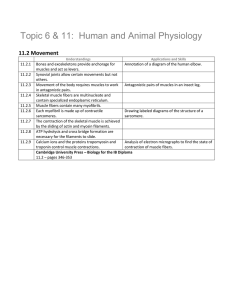

Seeley's Anatomy & Physiology Textbook, Thirteenth Edition

advertisement