CHAPTER Ill

HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE GROWTH OF

PETROLEUM INDUSTRY IN INDIA

Any study of the petroleum pricing policy would be incomplete without

an appreciation of the developments in the oil industry over the years. The present

chapter gives a brief account of the oil scenario that existed at the time of India's

independence and the developments in the areas of exploration and production,

refining. marketing and distribution, imports, production and distribution of natural gas,

and oil conservation.

Petroleum Industrv in 1947

Perhaps no other sector of Indian economy was so much neglected during

the British regime as oil. It was widely believed that excepting Digboi in Assam, there

was no oil elsewhere in India. Even Digboi remained neglected till 1921 when Burmah

Shell became its owner. The first refinery was built by the Assam Railway and Trading

Company in 1883 at Margherita. After the discovery of oil in the Digboi field, a new

refinery was commissioned in 1901 and the first kerosene from it was marketed in

December 1901. On the marketing side the Asiatic Petroleum Company entered the

Indian market in 1903 and later in 1921 the Burmah Oil Company (BOC) started

marketing in India. The Burniah Shell Company which was formed in January 1928

and the Standard Vacuum Oil ('on~pany (SVOC) which commenced its operations

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

in

13

September 1933 built extensive networks of distribution facilities throughout lndia.

Esso came to India on March 31, 1962 when the SVOC was reorganised and named

Esso Standard Eastern India, wholly owned by the Standard Oil Company (New

Jersey). The other major marketing companies were the Caltex Company (jointly

owned subsidiary of Standard Oil Company of California and Texas Oil Company), the

BOC (India Trading) Ltd, the latter operating exclusively in Assam and later known

as the Assam Oil Con~pany(AOC).' Thus the entire oil industry in India was under

the control of one or the other major international company. This was the position in

the entire non-Communist world, where seven companies known as the "Seven Sisters"

ruled the oil industry. These companies, also referred to as the international majors,

were the five US giants, Exxon, Gulf, Texaco, Mobil and Socal (Standard Oil of

California, later renamed Chevron), one British company (British Petroleum) and one

Anglo-Dutch company (Royal DutchiShell).

On the eve of independence, India's demand for petroleum products was

to the tune of about 2.2 million metric tons (mmt), of which roughly 0.2 mmt were

produced in the country and the balance was imported. In 1947 the production of

crude was 2,51,100tomes.

1

Est~mates ('onunittee; Fiftieth Report to the Fourlh Lok Sabha on the Ministy of

Petroleutrr and Chemicals. 1968

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

14

Independence and the declaration of the Industrial Policy Resolution of

1948 produced little qualitative change in India's oil policy. During the first three years

following independence, the share of local production of oil products ranged from 5

per cent to I0 per cent and, in the subsequent years, it fell to less than 5 per cent until

the beginning of a new phase in refinery construction in 1954.

Ex~loration and Production

For a long time even after Independence, the Government of India took

no serious interest in oil exploration. Somehow, the planners had very little faith in the

possibility of a substantial oil discovery and the nascent nation's technical expertise was

considered inadequate to undertake any exploration. More attention was therefore

given to refineries where there was no risk element. The balance of payments problem,

the growing level of oil consumption and the need for self-reliance in the major

petroleum products during the years following the Second World War made the

Govenunent

to assign a significant role to refinery construction in the nationai

economic agenda.

When K.D.Malaviya joined Nehru's cabinet and was given the charge of

Mineral Oil, a change in thinking took place in the Government that only if Indian

technicians were unable to prospect for oil, should the Government consider inviting

foreign companies for prospecting new areas. An Oil and Natural Gas Division was

created as a part of the Ministry of Natural Resources & Scientific Research in 1955.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

15

As suggested by N.A.Kaliin, the Soviet oil exploration consultant, and in pursuance

of the new Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956, oil exploration became a monopoly

of the Central Government. Consequently, the Oil and Natural Gas Commission

(ONGC) was set up in August 1956 as a Government department. The very structure

of ONGC rendered it incapable of undertaking exploration for oil on a scale that

would ensure self-reliance. It was only in October 1959 that ONGC became a statutory

Commission owned wholly by the Govenunent of India. Despite its limitations, ONGC

struck oil in Cambay in 1958. In 1972, the first offshore wells were drilled in Bombay

High, where too ONGC met with early success.

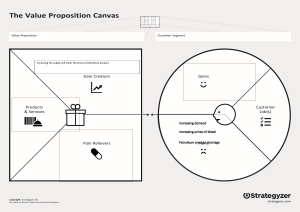

Table 3.1 which reveals a reasonably stable reserves1 production ratio

over the years is a record of ONGC's efforts to match the pace of exploration with the

increasing production and consumption. There has been a significant augmentation of

the recoverable reserves of both crude oil and natural gas, particularly after 'he

discovery of Bombay High. Although production has also been steadily on the rise, the

reserves1 production ratio has remained more or less constant around 25 because of

the discovery of new reserves. The physical significance of the ratio lies in the fact that

if production continues at the current level and no more reserves are found, the

current reserves will last only for 25 years. The need for accelerated exploration

cannot be overemphasized.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

Table 3.1

Reserves and Production of Cmde Oil and Natural Gas

Year

1947-48

1950-51

1960-6 1

1966-67

1970-71

1975-76

1980-81

1985-86

1990-91

1991-92

1992-93

1993-94

1994-95

Balance of

recoverable reserves

N.Gas

Crude

mmt

bcm

4.00

4.00

45.00

153.00

127.84

143.90

366.33

499.51

738.80

806.1 5

801.05

779.06

765.00

3.00

2.00

22.00

63.15

62.48

87.67

35 1.31

478.63

686.45

729.79

735.46

717.95

707.00

Production

Crude

mmt

0.25

0.26

0.45

4.65

6.82

8.45

10.51

30.17

33.02

30.35

26.95

27.03

32.23

RIP Ratio

N.Gas

bcm

N.A.

N.A.

N.A.

N.A.

1.45

2.37

2.36

8.13

18.00

18.65

18.06

18.34

19.38

Crude

Oil

16.00

15.38

100.45

32.92

18.74

17.03

34.87

16.56

22.37

26.57

29.72

28.82

23.74

Natural

Gas

43.24

37.02

148.99

58.84

38.14

39.14

40.7?

39.1:)

36.48

-

Note:

Reserves as on 1st January of initial year

mrnt = Million metric ton

bcrn = Billion cubic metres

N.A. = not available

Compiled from Indian Petroleum & Natural Gas Statistics, various issues

Source:

(Latest 1994-95)

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

17

Oil India Ltd. (OIL), the other public sector enterprise involved in

exploration and production, started as a joint venture of the Government of India with

Assam Oil Company/ Burmah Oil Company to exploit the oil fields of NaharkatiyaMoran- Hugrijan (Assam), discovered in 1953 by the latter. The Government's share

was increased to 50 per cent in early 1961 and OIL became a fully owned company of

the Government of India with effect from 14 October 1981.

Until the early 1970s. the oil exploration and production policy reflected

a desire to have a strong, national oil industry with all the necessary infrastructure.

With the oil crisis of 1973-74,the gravity of the situation was further emphasized. The

Fuel Policy Committee observed in 1974:

The oil policy of our country will have to be based on the

perspective that oil prlces are likely to prevail at a significantly higher

level than that anticipated in early 1973 and that India's dependence on

import of oil is likely to continue right upto 1990-91.. .

At the present price of crude in the international market, oil

exploration in India is an economically viable activity even if the risks

are rated high. ..All evidence points towards the need for speeding up

exploration activities particularly in the off-shore areas and selected onshore areas.

...there is urgent need to augment the capabilities of the ONGC

by providing them with more modem equipment and seismic exploration

vessels and off-shore rigs, and training our men in new technologies of

exploration. '

1

Report of the Fuel Policv Committee, 1974, paras 8.17.8.27

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

18

Shocked by the oil crisis of 1973, the policy makers in India renewed

their faith in coal, but in order to meet the demand for oil products and to reduce the

cost in terms of foreign exchange, the Committee recommended stepping up of oil

exploration, augmenting the capabilities of ONGC and participating in crude

production in the Middle East. Still, the planners emphasized reduced dependence on

oil and aspired for a self-reliant growth strategy based on coal. But such optimism soon

gave way to euphoria over oil when Bombay High was discovered.

Global bidding for oil prospecting and production was started in July

1980. Initially the exploration work was confined largely to the proven petroliferous

basins, while the demand was increasing steadily during the Sixth Plan period.

Therefore, a widening of the exploration base was considered necessary. The Economic

Survey, 1984-85 observed:

In order to stabilize the present reserves1 production ratio, it is

necessary to widen the area of exploratory drilling to cover sedimentary

basins with known occurrence of hydrocarbons, but from which no

commercial production has yet been obtained.

During the Sixth Plan period, the level of self- sufficiency rose from

about 35 per cent in 1979-80 to about 67 per cent in 1984-85. New discoveries during

this period, however, fell short of expectations, in spite of the 'accelerated' programme

of production of ONGC. This programme, approved in July 1982 envisaged speedier

development of Bombay High and satellite fields in the offshore during the Sixth Plan

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

to get an additional production of 12.04mmt. Acknowledging this failure, the Seventh

Plan made the following recommendation:

The individual discoveries and finds made were, in general, small,

suggesting that a similar pattern could prevail in the Seventh Plan as

well. Hence the need for intensifying exploration to inadequately

explored and unexplored basins.

Results obtained during drilling indicate the need for more

meticulous planning and preparation for drilling in those areas where

due to either greater depths or abnormal conditions, high pressures and

temperatures may be encountered. Since future exploration would

involve deeper drilling as well as drilling in such abnormal areas, it is

expected to be both costlier and time consuming.

With encouraging results obtained from water injecting

technology, its application to other areas is desirable. If not effective

application of other suitable enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques

would be required.'

While the first two bids for exploration in 1980 and 1982 did not attract

many international companies, the international companies showed encouraging

interest in the third round of bidding in 1986. Thanks to a more liberal package and

the prevailing international

environment, five foreign companies entered into

production sharing contracts (PSCs) for nine offshore blocks. However, this did not

result in any new hydrocarbon discovery.

During the Seventh Plan period, the national oil companies, ONGC and

OIL, yielded relatively more encouraging results. The total accretion in geological

Seventh Five Year

plat^.

1985-90, Vol 11, p. 129

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

20

resource during this period was 1536 mmt of oil and oil equivalent of natural gas,

exceeding the target of 1453 mmt in spite of the exploratory drilling meterage being

only 82 per cent of the target.

The fourth round awards were basically 'seismic options', wherein the

companies were required to commit only a small amount of capital to make a further

assessment and perhaps acquire a limited volume of geophysical data. They were not

required to give a firm commitment for drilling.

The 'rounds' system as practised in India during the 1980s has been very

cumbersome and it meant a delay of at least four years during which no new

exploration contracts could be granted to any one. These were the very years when

India's Balance of Payment problem became very alarming on account of heavy oil

import bills. A continuous process of bidding, whereby interested parties can be offered

suitable contracts without losing valuable time would have prevented

the delay.

Malaysia and Indonesia had reaped considerable benefits by giving up the policy of

'rounds' and replacing it with a policy whereby blocks were continuously offered round

the year.

Following the new investment policy announced by the then Finance

Minister Manmohan Singh in his budget speech of 29 February 1992, the Government

in July 1992 decided to offer oil blocks for exploitation to foreign and private

companies on a round-the-year basis. Under this liberalized policy, small discovered

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

21

oil and gas fields too were opened on a production sharing basis. Initially, 28 such

fields were offered for collaboration. T h ~ swas expected to result in an additional

production of approximately 8-9 mmt of oil during the Eighth Plan. The total

investment required for development of these 28 fields was estimated to be around

$450 million. The total oil reserves were estimated to be 57.62 mmt. of which 11.52

mmt were recoverable. The gas reserves in these fields were estimated at 7202 million

cubic metres (mcm) of which 5000 mcm were recoverable.

According to the Eighth Plan estimates, India has 21.31 billion tonnes

prognosticated

geological resources of hydrocarbons, which, by more intense

exploration efforts may perhaps be raised to 50 billion tomes or more. Of this, only

5.32 billion tomes have been established so far. Out of this, the recoverable oil

amounts to only 806 rnmt. The annual demand for petroleum is Likely to grow to about

120 mmt by the year 2000 AD. It is, therefore, possible for India to meet a major part

of her petroleum requirements for several decades to come, but it calls for a level of

investment unthinkable in the present economic conditions of the country.

The Eighth Plan strategy for exploration envisaged intensive exploration

of Category I basins, limited exploratory drilling with emphasis on close-grid seismic

data acquisition in the other basins, increased participation in overseas exploration

ventures, and greater emphasis on 3-D seismic surveys.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

22

The Rs.65,000 crore accelerated programme of exploration (APEX),

intended to make up for lost petroleum exploration efforts, has virtually remained on

paper. The focus of APEX, which was to be implemented over a three year period

1994-95 to 1996-97, was intensification of the efforts to add to crude oil reserves during

the Eighth Plan period through enhanced exploration in areas known to have crude oil,

upgradation of areas for formulating strategy for the Ninth Plan and beyond and

greater participation in overseas projects. However, an evaluation by the Planning

Commission has shown considerable slippage in the seismic surveys planned for 199495.'

Predominantly

smaller size discoveries were being made, which either

individually o r collectively did not promise any substantial and sustainable incremental

production of oil. If this trend persists, the domestic crude oil production may stagnate

or even decline in the Ninth Plan.

ONGC was restructured

on the lines suggested by the P.K.Kau1

Committee to relieve the resource crunch and to give greater autonomy. It was

converted into the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited, a public limited company

with effect from 1 February 1994.

To attract foreign investors and to provide a level playground for the

national exploring companies, the Government on 18 March 1997 announced a New

Exploration Licensing Policy (NELP), with the following initiatives:

...5

The Times of India, 3 January 1995

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

23

Companies, including ONGC and OIL, will be paid the international price of

oil for new discoveries made under the NELP;

Royalty payments will be fixed on an ad valorem basis instead of the present

system of specific rates;

Royalty payment for exploration in deep waters would be charged at half the

rate of 10 per cent for offshore areas for the first seven years after

commencement of commercial production. For onland areas, the rates would

be 12.5 per cent:

Half the royalty from the offshore area would he credited to a hydrocarbon

development fund to promote and fund exploration-related activities such as

acquisition of geological data on poorly explored basins, promotion of

investment opportunities in the upstream sector, institution building, etc;

Freedom for marketing of crude oil and gas in the domestic market;

Tax holiday for seven years after commencement of commercial production for

blocks in the North-East region;

ONGC and OIL will get the same duty concessions on import of capital goods

under the NELP as private PSCs;

Cess levied under the Oil Industry Development Act, 1974 will be abolished for

the new exploration blocks; and

A separate petroleum tax code will be put in place as in other countries to

facilitate new investments.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

24

The exploration blocks will be allotted on the basis of an open acreage system

which would allow companies to apply for exploration blocks without being

restricted to bidding rounds. '

This policy, based on the recommendations of the R-Group (See Chapter

12) is likely to be a major step towards dismantling the regulated regime in the

petroleum sector.

Refining

Action to establish refineries was initiated as early as July 1947 when the

Interim Government asked Burmah Shell, Standard Vacuum and Caltex to examine

the feasibility of setting up oil refineries in India. At that time they were primarily

interested in marketing and could meet their requirements with their own cheaper

products from the Middle East. They took advantage of the widespread belief that the

Indian geology outside Assam was not favourable to oil accumulation. They demanded

extraordinary assurances. includmg a guarantee against nationalisation, before any

refining or prospecting would be undertaken. The international companies changed

their stand on refinery construction and agreed to build refineries without insisting on

the "cost conditions" only when compelled by the Abadan crisis in Iran, where the

Government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq took over the 25 million ton

Excerpted from the Economic Times, 19 March 1997 and the Finance Minister's

Budget speech. 1997.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

25

giant Abadan oil refinery after disputes between the Anglo-Persian Oil company and

the Government could not be resolved through negotiations. Burmah Shell and

Standard Vacuum agreed to set up a refinery each in Bombay and Caltex agreed to

set up a refinery at Visakhapatnam.

It was only in the mid-fifties that the idea of public ownership of

refineries was translated into action. The immediate provocation was perhaps the

suicide of President Getulio Vargas of Brazil in 1954 which deeply stirred Nehru. In

a message to the nation released after his death, President Vargas had explained how

he was driven to such a desperate act by the pressure of the oil cartel which had a

complete grip on the main sectors of the economy. The American investors had been

reaping a return of as high as 500 per cent per annum on their Brazilian investments.

It was after considerable delay and consequent loss to the exchequer that

the work on the Barauni and Guwahati refineries could be started. The first public

sector refinery at Nunmati (Guwahati) went on stream on 1 January 1962 and in July

1964, the Barauni Refinely was commissioned. The Indian Refineries Ltd was already

registered in August 1958 to manage them. Later when the Koyali refinery was built,

the new company was entrusted with its management also. In September 1964, the

Indian Oil Company and Indian Refineries Ltd were merged into the Indian Oil

Corporation (IOC).

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

26

In September 1963, the Cochin Refineries Ltd (CRL) was incorporated

as a public limited company under a tripartite agreement between the Government of

India holding 51 per cent of the shares, Philips Petroleum Company of USA 25 per

cent, Duncan Brothers & Company Ltd of Calcutta two per cent and the balance held

by others. CRL went on stream in September 1966.

The Fom~ationAgreement of the Madras Refineries Limited (MRL) was

concluded on 18 November 1965 between the Govemment of India with 74 per cent

participation

III

the initial equity capital, and the National Iranian Oil Company

(NIOC) of Iran and Amoco India Inc of USA. This refinery was commissioned in

September 1969.

Only after the 1973-74 oil crisis was the need to match refinery

configuration to the quality of available crude and the production demand mix

recognized. Simultaneously, refinery location and the consequent distribution costs also

became important issues. The Fuel Policy Committee, 1974 recommended that:

...in

each plan period, there should be a very careful examination

u l the relinery locations, the product mix required in each refinery, the

extent of secondary processing to be established, and the feedstock

choiccs for the fertilizer industry should be examined by considering

these options s~multaneously,if necessary, with the help of programming

models. '

I

Relxw' ( 1 1 rhf, Fuel Po1ic.i. ( 'otnmitree. 1974, para 8.25

~

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

-

- --

27

By late 1970s, it became evident that middle distillates, particularly

kerosene and high speed diesel (HSD) would continue to account for a major portion

of the petroleum product consumption mix. The Working Group on Energy Policy

observed:

In view of the fact that the demand for middle distillates is large

in our country, process technologies to upgrade heavier fractions such as

LSHS to distillate products is of considerable importance.. . The Group

would like to emphasize the need for R&D which is directed towards

optimizing such process technologies. '

With debottlenecking,

the throughput capacity of several existing

refineries was increased since 1975. The Sixth Five Year Plan foresaw substantial

deficits in middle distillates. To increase the production of middle distillates, fluidized

catalytic cracker (FCC) facilities were installed in several refineries in the Sixth Plan

period. Soon. this technology was also found inadequate to meet the long-term

demands and the emphasis shifted to hydrocracking.

In order to meet the demand pattern, it is necessary to install

more of hydrocracker units instead of fluidized catalytic crackers. Till

such hydrocrackers come up, import of middle distillates may have to

~ontinueeven though there may be a surplus in somz of the petroleum

products like naphtha and bitumen.

The policy of establishing new refining capabilities also needs a

closer look.. .. The goal of total self-sufficiency to meet the entire

requirctnent of petroleum products .... and the argument that there is

-

Kr,poti

0/

rhe Working (;roup on Energy P o l i o . 1979, p 101

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

security of supply through national refining capacity does not hold good when

the crude has to be imported.. . OPEC is also expanding its refining capacity,

and in the none too distant future (by 1990), it is anticipated that at least 30 per

cent of its oil exports would be in the form of refined products. Capital costs

of new refineries have also gone up more than three-fold in the last five years

or so ...T

Even though the Panipat and Mangalore refineries did not take off

during the Seventh Plan period as planned, the refining capacity increased from 45.55

mmt in 1984-85 to 51.85 mmt at the end of the Seventh Plan period, due mainly to

capacity expansions of the existing refineries. It reached 56.4mmt per annum (mmtpa)

by 1 April 1995.

In recent years we are witnessing a complete reversal of the Government

policy towards setting up of refineries. While the philosophy in the late sixties led to

the take-over of the refining and marketing operations of the private companies, by

the late 1980s private companies were being encouraged to set up new refining

capacity in joint ownership with the national oil companies. Simultaneousiy, the

establishment of a number of refineries in other Asian countries opened up the issue

relating to crude oil versus product import. According to the Eighth Plan document:

In determining the refining capacity that needs to be added during

the Eighth and Ninth Plan periods, due consideration will be given to the

region-wise pattern of demand, the source of indigenous crude oil and

optimal choices regarding the location and technology of new refining

capacity.. . .Considering that indigenous crude availability in 1996-97 has

Econorr~ic.Survev, 3984/85. Chapter 7 , pp.2 1 -24

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

been targeted at 50 million tonnes and that in addition to this quantity, a minimum of

about 15 million tonnes of imported crude oil of appropriate quality needs to be

processed specially to meet the domestic requirement of lubricants and bitumen, it is

necessary to augment the refining capacity to about 65 million tonnes by 1996-97. Any

further addition to refining capacity will depend upon the relative economics of import

of crude oil vis-a-vis petroleum products.. ... In planning additions to the refining

capacity, highest priority will be accorded to cost-effective debottlenecking schemes

and low cost expansions. lo

In July 1992, the Government of India decided to allow private and

foreign investment in the refining sector. The public sector oil companies and the coventurers would have 26 per cent equity each and the balance 48 per cent would be

offered to the public. In line with this policy, the Government cleared the setting up

of three grassroot refineries with a capacity of 6 mmtpa each during the Eighth and

Ninth Plans. These are to be located in the Eastern, Central and Western India, with

IOC, the Bharat Petroleum Corporation 1,td (BPCL) and the Hindustan Petroleum

Corporation Ltd (HPCL) respectively as the public sector companies involved. The

Government also gave investment approval to set up the Assam accord refinery at

Numaligarh at a cost of Rs. 1830 crores. with a capacity of 3 mmtpa. The public sector

company involved is the indo-Bumah Petroleum (IBP).

At 6 per cent annual increase in product demand, India's product demand

in 1999-2000 will be 90.6mmt. At 7 per cent increase per year it will be 97.7 mmt. On

this basis India would need to build 45-52 mmtpa additional capacity to fully meet the

projected demands. Even assuming that al: of the planned 18 mmt of existing refinery

1"

Eighth Five Year Plan, 1992-97. L 01 11. p. 171

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

30

expansions go ahead, a minimum of 4 large scale refineries would need to be

completed by the year 2000. However, any new entrant in the refining sector has to

face significant barriers to entry on account of heavy depreciation advantage of the

existing refineries, marketing monopoly of the public sector and the restrictive

Government policies.

The Oil Industry Planning Group set up in 1994 under the Chairmanship

of U.Sundararajan, Chairman and Managing Director, BPCL estimated that the current

refining capacity deficit of 9.8 mmt would increase to 12.5 mmt by 2006-7. It was

projected that the demand for POL products would be 124.1 mmt vis-a-vis the present

level of 64 mmt. The investment required to develop the infrastructure for handling

this volume of products is in the range of Rs.42,000 crores to Rs.58,000 crores.

According to the Committee estimates, in 2006-7, the total refining capacity would be

11 1.6 mmt, conlprising of 67.3 mmt in the public sector, 27.6 mmt in the joint sector

and 16.7 nimt in the private sector.

Marketine and Distribution

At the time of independence,

the import of products and their

distribullon were mainly controlled by three foreign oil companies. Well over half this

trade was held by Burmah Shell, the other two being the Standard Vacuum Oil

Compaiiv 2uid Caltex.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

31

The Government entered the sphere

the Indian Oil Company was formed. The main objective was to supply oil products

to the state enterprises, which accounted for 10 per cent of the total oil consumption

in Inda. Subsequently, the Company's role was broadened to take over at least half

the import trade of the country and to market the products of state refineries. When

refineries, like CRL and MRL, partly controlled by the Government in collaboration

with foreign companies came into being, their products were also to be sold through

IOC, now the Indian Oil Corporation. In 1965, the Government prohibited import

trade by private oil companies and it became IOC's monopoly and by 1967, IOC

became the market leader with 35.5 per cent market share.

Distribution of petroleum products is a major area of concern as it adds

to the cost the consumer has to bear. The most economic means of long distance

transportation

is the pipeline, which is a relatively neglected area. The cost of

transportation per unit volume of oil by pipelines is roughly one-tenth of that by rail

or road tankers. Environmental and safety considerations also weigh heavily in favour

of pipelines. As the laying of pipelines is a capital intensive project, the Eighth Plan

stressed the need for attracting private investments in marketing operations.

To improve the supply conditions and to reduce the fiscal burden owing

to the sale of subsidised petroleum products and in line with the liberalised economic

policies, the Government

has set up Parallel Marketing System for Liquefied

Petroleum Gas (LPG), Superior Kerosene Oil (SKO) and Low Sulphur Heavy Stock

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

32

(LSHS, used as boiler fuel) since February 1993. Under this system, private parties are

allowed to import these products and market them through their own distribution

network at market determined prices. Safeguards were incorporated into the system

to prevent diversion of the kerosene and LPG marketed by the public sector

companies. "

India's foreign exchange reserve was dwindling over the years. The value

of imports of major oil products increased from Rs.309 million in 1947-48 to Rs.833

million in 1953-54 as a result of higher prices of oil, a higher level of consumption and

the currency devaluation of 1949. Although the Government took timely decisions to

bring oil imports under a licensing system, and also to prohibit imports of oil from the

dollar area, with which the balance of trade was very unfavourable, the position of the

foreign exchange fund was still precarious.

There was no import of crude till 1954 as there was no refining capacity

excepting the Digboi refinery with a capacity of 0.45 mmt only. Under the refinery

agreements the coastal refineries had been importing crude on their own and the

indigenous supply was limited to a small quantity from Ankleswar. Establishment of

I,

Economic Survey, 1995-96

~

~

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

33

refineries at Cochin, Madras and Haldia did not change this position. The gap between

indigenous production and demand kept on widening during the 1960s and 1970s.

To reduce dependence on the oil majors and to ease the balance of

payments problem, the Government in 1960 entered into an agreement with the USSR

to import crude. As the refineries refused to process Russian crude and the

Government lacked the will to retaliate in strong terms, the agreement was broken off.

The Government also imported HSD from the Soviet Union in August

1961, but it led to a price war between the oil companies and the newly born Indian

Oil Corporation as the former refused to handle Russian products in their marketing

networks. As the IOC did not have any retail outlets of its own, it could only sell to

the bulk consumers, particularly the state transport enterprises. The majors, in a bid

to retain their business, offered prices even lower than those quoted by IOC for its

Russian products. As a result, a large part of IOC's supply was unsold for a period of

time which also created storage problems. IOC then offered even lower prices which

were below economic level in order to secure some business. However, the price war

did not last very long as the oil companies were fully conscious of the serious risks to

which their large investments in India were exposed by these conflicts with the

Government.

Unlike the refineries, the marketing companies were not protected

against nationalisation through any agreement. The main objective of the price war was

apparently to put pressure on the Government to reject the proposals of the Oil Price

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

34

Enquiry Committee of 1961, which prescribed a lower schedule of prices for imported

products.

From May 1965, under pressure of the foreign exchange crisis, the

Government prohibited import of products by private oil companies and it became

IOC's monopoly. IOC could import oil from USSR and Rumania at cheaper than

world average prices, the price payable in rupees.

The first oil price increase of 1973-74 was associated with a balance of

trade deficit of Rs. 1,190 crores in 1974-75 which was 1.63 per cent of GDP and Rs.

1,229 crores in the next year (1.56 per cent of GDP). Correspondingly. the share of oil

imports in export earnings nearly doubled from 10.5 per cent in 1972-73 to 21.4 per

cent in 1973-74 and jumped to 33.4 per cent in 1974-75. (See Table 3.1). The

corresponding figures for the second oil crisis of 1979-80 were a terms-of-trade

deterioration of Rs. 2,725 crores or 2.38 per cent of GDP in 1979-80 and Rs. 5,838

crores or 4.3 per cent of GDP in 1980-81. The rise in the share of oil imports in export

earnings was from 28.4 per cent during 1978-79 to 50.9 per cent in 1979-80 and 78.5

per cent in 1980-81. Table 3.2depicts the impact of oil imports on India's balance of

trade. Thanks to the discovery of new petroleum reserves, the index of self-reliance

(Percentage share of indigenous production in total demand) had been steadily rising

in the 1970s and the 1980s. but this index has been falling in recent years.

U

Dasgupta; The Oil Industry in India, Some Economic Aspects, 1971, p.71

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

Table 3.2

I

ofP r I m

1

Year

Crude

Rs.Cr.

Products

Rs.Cr.

Total

Rs.Cr.

CIF

Value of

c~de

India's Total

imports Imports Exports

Rs.lMT Rs.Cr. Rs.Cr.

Note : Figures for 1994-95 are provisional.

Source : Indian Petroleum & Natural Gas Statistics (Latest 1994-95).

Economic Survey, Various issues.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

Balance

of

Trade

Rs.Cr.

Gross POL

imports

as %age

of total

exports

lndex

of Self

Reliance

% age

Table 3.3

Consumation of Major Petroleum Products: 1950-95 ('OW tons)

Year

1950-51

1955-56

1960-61

1965-66

1970-71

1974-75

1975-76

1980-81

1985-86

1990-91

1991-92

1992-93

1993-94

1994-95

LPG

.

8

46

176

289

336

405

1,241

2,415

2,650

2,866

3,113

3,434

MS

624

850

859

1,102

1,453

1,264

1,275

1,522

2,275

3,545

3,573

3,595

3,834

4,141

Total

704

850

983

1,370

2,697

3,423

3,596

4,388

6,776

9,801

10,115

10,310

10,570

11,637

SK

HSDO

Total

899

1,404

2,024

2,455

3,283

2,828

3,104

4,228

6,229

8,423

8,377

8,478

8,704

8,964

185

43 1

1,270

2,410

3,837

6,450

6,595

10,345

14,886

21,139

22,680

24,293

25,878

28,261

1,499

2,263

4,297

6,225

9,040

11,354

11,653

17,056

23,948

33,106

34,404

36,152

38,146

40,976

Grand total does not include refinery fuel and losses.

Note:Source: Govt. of India, Ministry of Petroleum & Chemicals: Petroleum &

Natural Gas Statistics. (Latest 1995-96)

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

Heavy

Ends

GRAND

TOTAL

37

Table 3.3 shows that from 17.9mmt in 1970-71, oil consumption rose to

30.9 mmt in 1980-81 and 55 mmt in 1990-91. This table presents the figures of

consumption of the major petroleum products from 1950 to 1995. It also gives the

break-up of total consumption in terms of light and middle distillates and heavy ends.

While illustrating the trends in consumption growth, this table also highlights the fact

that this growth was more pronounced in the case of the middle distillates. This'

important aspect of oil consumption will be analyzed in detail in Chapter 5. With

domestic oil production growing at a much slower rate, this rising consumption has

necessitated increasingly larger imports of crude oil and petroleum products. The

import bill of c ~ d eand petroleum products skyrocketed from Rs. 136.63 crores in

1970-71 to Rs. 5,266.49crores in 1980-81 and more than doubled during the next 10

years as a result of the increased volume of import as well as a rise in international

price of crude oil and petroleum products. (See Table 3.1)

The total demand for petroleum products in the terminal year of the

Eighth Plan has been estimated to be about 81 mmt. Even if the ambitious crude oil

production target of 50 mmt in 1996-97 is achieved, the level of self-sufficiency will be

below the 60 per cent level achieved at the end of the Seventh Plan period.

lndia has been a net importer of petroleum products from the very

beginning. There appears no improvement in this status at least for several years to

come, as the production is not likely to keep pace with the demand in the near future.

The countries from where India has been importing oil include Iran, Iraq, Saudi

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

38

Arabia, UAE and the erstwhile USSR. Most of these countries have been facing

internal problems or international hostilities in the recent past and this has created

difficulties for India both in terms of availability and price. The import policy,

therefore, will always remain influenced by international politics including oil politics.

At the same time, since the oil imports bill constitutes nearly 2 per cent of the GNP

(as in 1990-91) and 25-30 per cent of the total import of the country, the fluctuations

in international market prices seriously affect the balance of payment situation and

bring inflation and other pressures on the economy.

Assuming that the ratio of oil imports to total export earnings continue

to remain at around 32 per cent and the price of oil in the international market would

not be higher than $22 per barrel by the year 2010-1 1, India's POL import bill is likely

to reach a level 3 or 4 times the present level, depending on which of the various

projections of demand comes true. (See Chapter 4 for demand projections). Apart from

the balance of payments problem, this will make the country more vulnerable to

sudden hikes in oil prices.

Natural Gas

Natural gas is often found in its free form as well as in association with

oil. Table 3.4depicts the relation between production and utilization of oil and natural

gas. While it had been possible to utilize the entire crude oil produced, a substantial

portion of the natural gas produced

i11

the well had either to be re-injected or flared

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

Crude in rnmt

Natural Gas in bcm

Year

1947-48

1950-51

1960-61

1966-67

1970-71

1975-76

1980-81

1985-86

1990-91

1991-92

1992-93

1993-94

1994-95

Refinery

crude

thruput

0.25

0.26

6.13

12.71

18.38

22.28

25.84

42.91

51.77

51.42

53.48

54.30

56.53

Production

0.23

0.23

5.78

11.88

17.11

20.83

24.12

39.88

48.56

48.35

50.36

51.08

52.93

Production

na

na

na

na

1.45

2.37

2.36

8.13

18.00

18.65

18.06

18.34

19.38

Natural Gas

ReFlared

injected

0.04

0.16

0.07

0.07

0.10

0.13

0.09

0.07

0.23

Source: lndian Petroleum & Natural Gas Statistics (Latest 1994-95)

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

0.76

1.08

0.77

3.12

5.13

4.07

1.85

1.92

2.02

Net

Production

0.65

1.12

1.52

4.95

12.77

14.44

16.12

16.34

17.34

40

due to technical reasons or lack of infrastructure. The production of gas increased from

1.45 billion cubic metres (bcrn) in 1970-71 to a mere 2.36 bcm in 1980-81, of which

only 1.52 bcm was used. Thereafter the production and utilisation of natural gas has

grown faster.

Gas is not merely a source of energy. It is also an excellent raw material

for several petrochemicals. Each component of its fractionation has its own use. The

lightest component methane can be used to manufacture urea, for power generation

and in the manufacture of several industrial products like sponge iron. It can also be

converted to methanol which is increasingly being used as a fuel and as a raw material

in the chemical industry. It can even be converted to diesel oil. The other constituents

like ethane and propane can be used to manufacture ethylene and propylene, the basic

building blocks of the petrochemical and synthetic fibre industries.

Another major component of natural gas is LPG. LPG consumption in

India increased from 1,76,000 tonnes in 1970-71 to 4,05,000 tonnes in 1980-81 and

24.15.000 tons in 1990-91. Since India is a net importer of kerosene, it is necessary to

reduce our dependence on kerosene. For heating purposes, LPG is a better substitute

but there is need to make it more easily avdable to domestic consumers. The reduced

dependence on kerosene is a remedy for our middle distillates problem. Since there

are different uses for gas, the distribution will have to depend on its opportunity cost.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

41

During the Seventh Plan period great emphasis was laid on the increased

exploitation of Natural Gas. Recoverable reserves of Natural Gas went up by about

40 per cent during the Seventh Plan period, while production went up by almost 2.5

times during the same period. Gas utilisation has also become more varied. In the early

eighties, Natural Gas was kept reserved only for fertilizer plants.

increased

.domestic availability, gas based power plants, petrochemical units and other industries

could also be set up. In spite of this emphasis and the fact that the total production of

Natural Gas during the Seventh Plan was 59.65 bcm, against a target of 59.68bcm, the

actual despatches to consumers were only 40.41 bcm. About one-third of the gas

produced had to be tlared due to technical constraints, non-lifting by consumers, nonavailability of down-stream facilities for utilising gas and also inadequacy of

compression and transportation facilities for associated gas. The Eighth Plan, therefore,

emphasised the need to eliminate the flaring of natural gas at the earliest, in any case

not later than 1996-97. Still, the Eighth Plan projected a natural gas demand of only

25 bcm against an estimated domestic availability of 30.18 bcm by 1996-97. The

planners observed:

It is assumed that half of the prognosticated reserves represents

natural gas, of which only 12 per cent has been till now established. The

possibility of discovering significant reserves of natural gas in the future

will need to be kept in view for the purpose of planning. *

LT

Eighth Five Year Plan, 1992-97, Vol 11, p. 161

- --

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

-.

42

The Gas Flaring Reduction Project of ONGC requiring an investment

of Rs. 7500 crores is funded by ONGC from its own resources to the tune of Rs. 2860

crores, the rest coming from World Bank (US $450 million), ADB and Japan Exim

Bank. By the end of the Eighth Five Year Plan, gas utilization is expected to go up to

about 80 million cubic metres per day which is about 27 mmt of oil equivalent. By

1995, the gas flaring has come down to 6.4per cent. (See Table 3.4).

Unless natural gas is extensively used as a fuel in vehicles or in power

generation, its availability is not going to make any substantial difference to the level

of crude or product imports. The Advisory Board on Energy had recommended that

in view of the abundant availability of gas,particularly in the Western Region, and in

view of the emerging bottlenecks in the transportation of coal along with a drop in

coal quality. we have to rethink past gas utilization policy and plan for the greater use

of gas in power generation, at least till such time that we are able to sort out coal

transportation problems and improve efficiency of coal use. With an improvement in

the use of gas for power generation, industrial production would increase, and to that

extent imports of some commodities could decline and exports of some commodities

could increase. As an efficient substitute for diesel, natural gas can reduce dependence

on HSD for use in generating sets in industry, and in agricultural pumping operations.

As will be shown in later chapters, our hydrocarbon problem is

essentially a liquid fuel problem and if we are to use our gas reserves to alleviate this

problem, we will have to consider the use of gas (a) to substitute for diesel in vehicles;

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

43

@) directly in homes as cooking fuel; and (c) as boiler fuel in industry. So far, very

little headway has been made along these lines. The Advisory Board on Energy

pointed out that if we assumed that by 2004-05, a gas supply of 60 mcmd could be

possible and of this one-brd would be used to substitute for liquid fuels, then about

6 mmt of crude equivalent could be saved.

India's balance of recoverable reserves of natural gas is estimated to be

over 700 bcm, which at the current rate of production of nearly 20 bcm is expected to

last over 35 years. (See Table 3.1). More intensified exploration is required to maintain

thls RIP ratio at least at this level.

Oil Conservation

Oil conservation became an important part of our economic agenda only

after the oil crisis of 1973. The Economic Survey, 1973-74 stated:

In order to mlnimise the impact of outback in oil availability, it

is important that use of fuel oil in industry is economised, and that cuts

are introduced in a planned and phased manner so as to derive the

optimum combination of industrial output from a given amount of oil

supply.

There is a strong correlation between GDP and energy consumption as

may be seen from Table 3.5 and Figure 3.1. Here GDP at factor cost has been shown

at 1980-81 prices. Consumption figures include refinery fuel and losses.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

G D P - C ~ ~ ~ u m ~ tCorrelation

ion

(A11 Petroleum Product&

Year

GDP at Factor

Cost (Rs.Crs)

1980-81 prices

Consumption

in mmt

42,871

45,117

49,895

54,086

57,487

62,904

66,228

74,858

72,856

80,841

90,426

91,048

96,297

106,280

120,504

122,427

133,915

150,433

163,271

188,943

209,791

221,168

238,900

Sources:

Compiled from:

1. Economic & Political Weekly, 10 October 1992

2. Indian Petroleum & Natural Gas Statistics,

various issues (latest 1994-95)

3. Economic Survey, Various issues

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

46

Figure 3.1 shows that for every one per cent increase in our national

income, our demand for petroleum increases by more than 1 per cent. Thus the

demand, which stabilized around 23 mmt after the oil crisis of 1973 could not be

suppressed for long. It picked up again to 29.65 mmt in 1979-80 and reached 54.1 mmt

by 1989-90, the terminal year of the Seventh Plan, showing an annual average growth

rate of 6.9 per cent. Thereafter, during 1990-91 and 1991-92, it was around 1.7 per cent

due to demand containment. Realising this dependence of development on oil, the

Sixth Plan conceded that.

...giventhe stage of development of the country and the limited

technological options specially in the transport sector, holding the

demand for petroleum products to a manageable level will pose a

formidable challenge. "

Several measures have been adopted by the Government to promote

conservation of petroleum products in the transport, industrial, agricultural and

household sectors. These include practices to increase fuel efficiency, training

programmes in the transport sector, replacement of inefficient boilers and furnaces

with efficient ones, promotion of fuel-efficient technologies and equipment in the

industrial sector, standardisation of fuel-efficient irrigation pump sets in the agricultural

sector, promotion of fuel-efficient stoves in the domestic sector, etc. The Petroleum

Conservation Research Association (PCRA) was set up to develop and promote new

oil conservation measures and to create awareness among oil users.

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam

47

Other potential methods of oil conservation include quality upgradation

of lubricants and inter-fuel substitution. Examples of inter-fuel substitution include

replacement of kerosene in the textile pigment printing with synthetic thickeners, use

of compressed natural gas (CNG) as automotive fuel, blending methanol and ethanol

with petrol (Motor Spirit or MS), promotion of non-conventional sources of energy,

battery-operated vehicles, encouraging the use of coal in boilers, etc.

The strategy recommended for demand management in the Eighth Plan

are :

(a)

lmprovement in the efficiency of use of petroleum products in different

sectors of the economy,

@)

Promotion of demand management programmes aimed at reducing the

011-intensity of the consuming sectors, and

(c)

kncouraging substitution of petroleum products by coal, natural gas,

electnclty, etc.=

-

IS

-

-

Eighth P,vr Year Plan, 1992-97, Vol 11, p.169

Prepared by BeeHive Digital Concepts Cochin for Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam