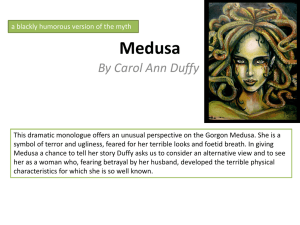

Medusa and the Female Gaze Author(s): Susan R. Bowers Source: NWSA Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), pp. 217-235 Published by: Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4316018 Accessed: 05-11-2015 11:40 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to NWSA Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze Susan R. Bowers The patriarchal images of women from Greco-Roman mythology will continue to oppress as they remain "encoded within our consciousness."' The task for feminist scholars and teachers is to expose the depth and profundity of these images in the Western psyche and discover how to reconstruct images of women that represent their complexity and power. The mythological figure of Medusa, that primary trope of female sexuality, is a good example of how profoundly the male gaze structures both male and female perceptions of women and of the antidote to the male gaze.2 Medusa's mythical image has functioned like a magnifying mirror to reflect and focus Western thought as it relates to women, including how women think about themselves. The Greco-Roman Medusa, however, is actually a perversion of a matrifocal culture's goddess. Rediscovering and remembering the vitality and dark power of that Medusa can help women to re-member themselves. What follows is a history and analysis of how Medusa has evolved in patriarchal culture and a report on how contemporary women artists are turning to this matriarchal image for inspiration and empowerment. These artists demonstrate how the same image that has been used to oppress women can also help to set women free. Female eros is "assertion of the life force in women, of creative energy empowered,"3 but it has undergone continuous assault from the male gaze, for "men do not simply look; their gaze carries with it the power of action and of possession."4 I recently discovered by accident an outstanding example of the abuse of female eros by the male gaze. A drawing by German expressionist George Grosz was being used as an illustration for a scholarly article. What I saw was a headless, bloody, Correspondence and requests for reprints should be sent to Susan R. Bowers, Department of English, Susquehanna University, Selinsgrove, PA 17870. 'Annis V. Pratt, " 'Aunt Jennifer's Tigers': Notes Towards a Preliterary History of Women's Archetypes," Feminist Studies 4 (February 1978): 171. 2See E. Ann Kaplan, Women and Film (New York: Methuen, 1983) for an elaboration of "the male gaze." 'Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider (Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press, 1984), 53. I base my discussion of female eros on Lorde's definitions. 4John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Harmondsworth, N.Y.: Penguin Books, 1982), chap. 3. NWSA Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2, Spring 1990, pp. 217-235 217 This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 218 Susan R. Bowers partially naked woman lying upon a bed, her lifeless arms still clutching her upper torso, a hatchet resting by her shoulder, while her murderer leered from the washstand washing blood from his hands. The combination of mutilation, and death, and a murderer's leer was nightmarish, but the reaction to the drawing by the author of the article was almost worse. He pointed out that it contained "joy, excitement . . . and the ludicrous."5 Susan Griffin's comments on the nude female body illuminate this scholar's reaction, which is at the foundation of the patriarchal construction of Medusa. The nude body of woman recalls for us our mothers, our infancy, our vulnerability, the knowledge of our body, and the meaning of nature, recalls to us our mortality. Therefore, pornography, wishing to forget all this knowledge, defames that body, ridicules it, punishes it, tries to destroy the power of its presence in our minds.6 The male scholar who sees joy and excitement in the depiction of a woman's mutilation and murder participates with the murderer in the defamation and attempted destruction of eros, that "whole range of human capacity."7 Without a head, the woman in the drawing can threaten neither the man with her nor the male spectator with her own subjectivity. Her mutilated body is a symbol of how men have been able to deal with women by relegating them to visual objectivity. The history of women's images in Western culture is the history of an attempt to defuse the power of female eros. The antidote to the male gaze, and one avenue to women reclaiming their own sexuality, is the female gaze: learning to see clearly for themselves, thus reconstructing traditional male images of women. Women in the fourteenth century, for example, "got positive and fruitful messages from images of women that were 'figures in the men's drama.' "8 The Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene, however, were attractive to many women because they "provided models of a spiritual life liberated from immersion in the potentially overwhelming biological contingencies of childbearing and the physical and environmental necessities of household, farm, or business."9 Unlike the spiritualized images of the Virgin 5Peter Fingesten, "Delimitating the Concept of the Grotesque," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 42 (Summer 1984): 422. Fingesten's reaction is far from unique. It resembles the comment of Johann Jakob Bachofen on Achilles having fallen in love with the Amazon Penthesilea after killing her in battle: "Given back to the limitations of womanhood, she awakens the man's love." Myth, Religion and Mother Right (Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 1967), 130-31. 6Susan Griffin, Pornography and Silence (New York: Harper & Row, 1981), 261. 7Griffin, Pornography, 254. 8Margaret R. Miles, Image as Insight (Boston: Beacon Press, 1985), 64. 9Miles, Image, 88. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 219 Mary and Mary Magdalene, Medusa is charged with a profound sensuality and physicality that cannot be purged from her matriarchal origins. In particular, I am suggesting that a feminist reading of Medusa will reveal that she is actually the icon of the female gaze, that powerful expression of female subjectivity and creativity. The great irony of Medusa is that she has become a classic example of the female object, though the greatest emphasis in the Medusa myth is the terrifying power of her own gaze. Psychoanalytic theory has decided that Medusa was "the terrible symbol of the female genital region," because the "penis-less" genital appeared to the child as castration.'0 Freud remarked of the Medusa head: This symbol of horror is worn upon her dress by the virgin goddess Athena. And rightly so, for thus she becomes a woman who is unapproachable and repels all sexual desires-since she displaysthe terrifying genitals of the Mother. Since the Greeks were in the main strongly homosexual, it was inevitable that we should find among them a representation of woman as a being who frightens and repels because she is castrated." Freud's and Sandor Ferenczi's psychoanalytic theory conceives of female genitals as terrifying images of male castration because it is rooted in the male perspective. By transforming Medusa's head into the image of profound lack, Freud and Ferenczi deflect attention from the compelling, frightening presence of Medusa's eyes that are watching with all the force of a powerful subjectivity. According to Hazel Barnes, "it was not the horror of the object looked at which destroyed the victim but the fact that his eyes met those of Medusa looking at him."'2 She agrees with Jean-Paul Sartre: ". . . when another person looks at me, his look may make me feel that I am an object, a thing in the midst of a world of things. If I feel that my free subjectivity has been paralyzed, this is as if I had been turned to stone."'3 The "Look" is so disturbing because it constitutes judgment of the self from outside the self, judgment which can neither be controlled nor even known precisely. The Look of the Other, which reveals to me my object side, judges me, categorizes me; it identifies me with my external acts and appear'0Sandor Ferenczi, "On the Symbolism of the Head of Medusa," trans. Olive Edmonds in Further Contributions to the Theory and Technique of Psychoanalysis, comp. John Rickman (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1927), 360. "Sigmund Freud, "Medusa's Head," vol. 5 of CollectedPapers, ed. James Strachey (New York: Basic Books, 1959), 105-6. '2Hazel Barnes, The Meddling Gods (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974), 13. "3Barnes, The Meddling, 22, as paraphrased from Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness (New York: Philosophical Library, 1956). This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 220 Susan R. Bowers ances, with my self-for-others. It threatens, by ignoring my free subjectivity, to reduce me to the status of a thing in the world. In short, it reveals my physical and my psychic vulnerability, my fragility.'4 The Medusa complex, then, "represents my extreme fear that by denying my own freely organized world with all of its connections and internal colorations, the Other's look might reduce me permanently to a hard stonelike object."'95 Patriarchal males have had to make Medusa-and by extension, all women-the object of the male gaze as a protection against being objectified themselves by Medusa's female gaze. The defense against having their own free subjectivity ignored, their vulnerability and fragility revealed, and their world shared was the destruction of female subjectivity. But one has to wonder at the extremes to which male artists and myth-makers have gone. Why was it necessary to destroy female subjectivity? The answer lies in Medusa's powerful pre-Olympian history. What we now know is that Medusa was a powerful goddess at a time when female authority was dominant and the power to be feared was feminine.'6 As the serpent-goddess of the Libyan Amazons, for example, Medusa represented women's wisdom. A female face surrounded by serpent-hair was an ancient, widely-recognized symbol of divine, female wisdom. Some feminists suspect that the Gorgons were a Black Amazon tribe.'7 As Neith of Egypt and Athene in North Africa, Medusa represented the Destroyer component of the Triple Goddess. Her inscription at Sais named her "mother of all the gods, whom she bore before childbirth existed." She was "All that has been, that is, and that will be."'8 The snakes on her head are strong mythological symbols associated with wisdom and power, healing, immortality, and rebirth. Medusa was obviously more than a mother goddess, perhaps originally both the giver of life and death, and the giver of rebirth and immortality. Why the prohibition against gazing directly at her? One explanation suggests that her blood was magic because it represented menstrual blood: primitive people believed a menstruating woman's look could turn a man to stone.'9 But others remind us simply that mortals must never look a deity in the face.20 "It is never wise in myths and fairy tales to look 4Barnes, The Meddling, 23. "5Barnes, The Meddling, 23. '6Thalia Feldman, "Gorgo and the Origins of Fear," Arion 4 (Autumn 1965): 484-93. 17Emily Erwin Culpepper, "Ancient Gorgons: A Face for Contemporary Women's Rage," Woman of Power 3 (Winter/Spring 1986): 22. 'Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology(London: Hamlyn, 1968), 37. "9SirJames Frazer, The Golden Bough (New York: Macmillan, 1922), 696, 699. 20Edward Phinney, Jr., "Perseus' Battle with the Gorgons," Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 102 (1971): 446-47. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 221 certain women, death, or gods in the face because their unmediated the sun in eclipse."'2' Because of Medusa's power is too great-like powerful image, she was represented on the Temple of Artemis on Corfu, apparently to protect the temple from evil: Medusa is intact and unmolested. Perseus does not figure here because the scene does not exist to glorify any hero. Medusa, and her children, and her lion companions, function here entirely in an apotropaic aspect-to turn away evil from the temple and the goddess within . . . The entire scene on the pediment is one of teeth, fury and dark power.22 When the invading Hellenes arrived, they "wrecked the goddesses' shrines and tore off the masks from the priest-women, an episode in that crucial moment of western civilization when female powers were replaced by gods and heroes."23 Medusa's murder, according to Joseph Campbell, exemplifies the stories justifying usurpation of pre-Olympian goddess figures by the invaders: "Wherever the Greeks came, in every valley, every isle, and every cove, there was a local manifestation of the goddess-mother."24 The Olympian Medusa first surfaces in Hesiod's Theogony(8th century B.C.) as the mortal sister of the Graiai, one of the three Gorgons: Dark-maned Poseidon lay with one of these, Medousa, On a soft meadow strewn with spring flowers. When Perseus cut off Medousa's head, immense Chrysaor And the horse Pegasus sprang forth.25 The divine, Hesiod. lodorus beheld Olympian Medusa lacks sacred power. The male, Poseidon, is not the female. Nor is Medusa's petrifying look mentioned in However, by the second century A.D., the legend told by Apolstates of the Gorgons that "They turned to stone those who them."26 As Annis Pratt explains, Myths in which heroes conquer dragons and gorgons and snakes and other monstrous figures are essentially stories of "riddance" in which the beautiful and powerful women of the pre-Hellenic religions are made to seem horrific and then raped, decapitated, or destroyed.27 2INor Hall, The Moon and the Virgin (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), 65. 22Tamsey Andrews as quoted in Culpepper, "Notes on Gorgons," unpublished paper, n.d., 5. 23Joan Coldwell, "The Beauty of the Medusa: Twentieth Century," English Studies in Canada 1 (December 1985): 423. 24Joseph Campbell, Occidental Mythology(New York: Viking Press, 1964), 149. 25Hesiod, "Theogony," in Hesiod, trans. Richmond Lattimore (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1959), 139. 26Apollodorus, The Library, trans. Sir James George Frazer, vol. 1 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1959), 161. 27Pratt, " 'Aunt Jennifer's Tigers'," 168. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 222 Susan R. Bowers In Ovid's Metamorphoses (1st century B.C.), Medusa is a young girl whose "beauty was far-famed." Because she was raped by Poseidon, the god of the sea, in Athena's shrine, Athena, "for fitting punishment transformed / The Gorgon's lovely hair to loathsome snakes."28 The young hero Perseus killed Medusa by using his bronze shield to reflect the "ghastly head" so that he could sever it. Even in death, the Medusan head retained its power, and Perseus used it to turn his enemies to stone. Ovid portrays Perseus's respect for Medusa's force when he shows how the hero's careful treatment of the head produces what we know as coral: . . .lest the snake-girt head Be bruised on the hard shingle, [he] made a bed Of leaves and spread the soft weed of the sea Above, and on it placed Medusa's head. The fresh seaweed, with living spongy cells, Absorbed the Gorgon's power and at its touch Hardened, its fronds and branches stiff and strange. The sea-nymphs tried the magic on more weed And found to their delight it worked the same.29 The grotesque paradox of the Olympian Medusa is the juxtaposition of her extraordinary beauty and her horror, which is represented by the writhing serpents on her head and her power to petrify. She is paradoxical in more than one sense: blood which flowed from her right side created a life-giving drug which permitted Asclepius to bring six mythical beings back to life, whereas blood from her left side produced poisonous snakes.30 The Olympian Medusa has become "a myth of origin for amulets" because her head "literally combines and contains evil mixtures and confuses the sacred and profane, law and taboo, pure and impure . . . contagion and cure," and the purpose of the amulet is to baffle, to create confusion.31 I believe Medusa's paradox reflects in part the coexistence of her pre-Olympian and Olympian history: "A memory of the beauty of the goddesses remained encapsulated in the captured spirit, particularly of women."32 The two most famous art works inspired by this Medusa are Benvenuto Cellini's sculpture Perseo and the painting Head of Medusa in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Cellini's work captures magnificently the ambiva28Ovid, Metamorphoses,trans. A.D. Melville (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 4.800-801. 29Ovid, Metamorphoses,4.741-49. 30Philip Mayerson, Classical Mythology in Literature, Art, and Music (Lexington, Mass.: Xerox Corporation, 1971), 131-32. "1Tobin Siebers, The Mirror of Medusa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 8-9. 32Pratt, " 'Aunt Jennifer's Tigers, ' " 168. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 223 lence of the Olympian Medusa. When seen from behind, Perseus and Medusa look very much alike. His tangled curls mimic the coils of her twining snakes, and the hero and his victim have identical profiles, "presenting a baffling spectacle for those in need of clear distinctions between the heroic and the monstrous." The body of Cellini's Medusa is feminine and fragile, while her murderer is Janus-headed.33 In the foreground of the Uffizi painting, serpents writhe on her head, the beautiful dead face of Medusa seeming to gaze at the heavens while a vapor escapes from her mouth. Like Cellini's sculpture, the painting is tense with ambivalence: neither completely horrible, because of the beautiful face, nor thoroughly lovely, because of the morbidity and snakes. The bewitching mixture of female beauty and horror echoes the interpretations of Perseus and Medusa during the Middle Ages. In the Romance of the Rose, for example, Perseus arms himself "with the mirror of reason to resist the dangerously feminine, to neutralize the erotic power that threatens to immobilize him."34 Arnulf of Orleans, analyzing Lucan's Pharsalia, explains Medusa's effects on men as the results of sexual attraction.35 Dante's Medusa is called by three infernal furies while the pilgrim and Virgil wait at Lucifer's gate. Virgil advises Dante: "Turn your back and keep your eyes shut tight; for should the Gorgon come and you look at her, never again would you return to the light.' 36 Virgil actually places his own hands on Dante's to hold the pilgrim's eyes shut because this is "an Evil upon which man must not look if he is to be saved."37 This Dantean Medusa is believed to represent "a sensual fascination and potential entrapment, precluding all further progress" for the pilgrim.38 Art historian Margaret Miles point out that in the fourteenth century, women's sexuality and biological experience were pointedly rejected in favor of an idealized female image. But Miles and others have found strong evidence that women at this time had considerable power in business, politics, and the church. "Siebers, The Mirror, 12-13. 34Sylvia Huot, "The Medusa Interpolation in the Romance of the Rose: Mythographic Program and Ovidian Intertext," Speculum 62 (October 1987): 874. 35Reported in Huot, "The Medusa Interpolation," 874. 3"Dante, The Inferno, trans. John Ciardi (New York: New American Library, 1954), canto 9, lines 52-54. 37Ciardi, "Introduction," in Dante, The Inferno, 9. "8John Freccero, "Dante's Medusa: Allegory and Autobiography," in By Things Seen: Reference and Recognition in Medieval Thought (Ottowa: University of Ottowa Press, 1979), 39. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 224 Susan R. Bowers The spiritual autonomy of such women may have been deeply frightening to patrician men. The device of simultaneouslydistancing women and informing them of the role within the communitythat men preferred them to play made images of women attractive to men. For men, the totally visualized and spiritualized-silent and bodiless-woman was manageable.39 The ethereal women of fourteenth-century paintings do not represent actual women but "the qualities men would have liked women to emulate [as] 'a way of mastering' what was otherwise too immediate, too threatening, too intense."40 Because she triggered the unconscious memory of the beautiful, matriarchal goddesses, Medusa became the emblem for what these men most feared: sensual and powerful women. By the romantic period, however, male artists had discovered a new way to combat the female power and subjectivity that Medusa could not help but project from her pre-Olympian days. Medusa's victimization by Poseidon and Perseus, but especially by Athena, who punished the victim instead of the rapist, contributed to her becoming a "key Romantic iconograph."'41 "Although Romantic artists were all aware that she was, in some sense, a focus of evil, they generally agreed that she was innocent of the horror she generated and that their own fascination was with her betrayed power and innocence."42 Shelley, who incorrectly attributed the Head of Medusa in the Uffizi Gallery to Leonardo da Vinci, presented her as a victim of tyranny in his poem "On the Medusa of Leonardo da Vinci in the Florentine Gallery." Fellow romantic William Morris agreed. Morris was attracted to her because she is beautiful and suffering. In his version, however, Medusa longs to die but "no one will release her from her death-inlife because all men are . . . themselves afraid of dying." By killing Medusa Perseus conquers the fear of death, and our sympathy for his act reifies that conquest in the audience. . . . To be ready to kill what we love . . . is to have removed any subservience to the instinctive possessivenesswhich all these Romantics are attacking. . .. In Morris' story, when Perseus slays the Medusa a hero is born who . . .sets his highest desires within the framework of his own human creativity:love, integrity, civilization. Like all Romantic heroes, Morris' Perseus aims to create his own values.43 By transforming Medusa into a victim, Morris domesticates her and her terrible power dissipates. But in making her the necessary victim for a 39Miles, Image, 83-84. 40Miles, Image, 85. 4'Jerome J. McGann, "The Beauty of the Medusa: A Study in Romantic Literary Iconography," Studies in Romanticism 11 (Winter 1972): 3. 42McGann, "The Beauty of the Medusa," 4. 43McGann, "The Beauty of the Medusa," 20-21. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 225 hero, demonstrating his victory over the fear of death, his desire for "love, integrity, civilization," Morris inscribes a prominent aspect of the original myth: Medusa's role as sacrificial victim. As Rene Girard, who focuses on the function of ritual sacrifice for a community, explains: "Society is seeking to deflect upon a relatively indifferent victim, a 'sacrificeable' victim, the violence that would otherwise be vented on its own members, the people it most desires to protect."44 Girard argues that sacrificial victims, whether human or animal, can be distinguished from "nonsacrificeable beings" by their lack of a crucial social link with the community that enables them to be sacrificed without fear of reprisal.45 While he declares that women are rarely sacrificial victims, I contend that Medusa represents the paradigm of the woman as eminently "sacrificeable." By being marginal to the patriarchal community, she meets Girard's criterion of sacrificial suitability. She provokes such a violent defense because she represents such intense female erotic power and strength, and she shares these characteristics with millions of women executed as witches who, like the Medusa, provided a focus for womanhating in a male-dominated society. Girard attempts to explain what he believes to be the scarcity of women among sacrificial victims by noting the property value of women. The married woman retains her ties with her parents' clan even after she has become in some respects the property of her husband and his family. To kill her would be to run the risk of one of the two groups' interpreting her sacrifice as an act of murder committing it to a reciprocal act of revenge.46 Medusa and women like her-not owned by the patriarchy-are ideal victims. Destroying them does not challenge male property rights and does not damage those women who serve a patriarchal society. Sacrifice of Medusa-women enables the male communal expression of anger and violence that female eros and power provoke. Whereas Medusa's slaughter is symbolic, and no actual blood is spilled, the impact of her symbolic murder is profound for both women and men since it demonstrates the attempted destruction of real female power. Her gender is the prime determinant of male response; she becomes for the male romantics the trope of the Dark Woman, the Belladonna who mystifies, seduces, and destroys. Morris's domestication of Medusa appears late in the romantic period-after Shelley, Pater, and Swinburne have focused on the paradox of her dark beauty and power. Swinburne 44Rene Girard, Violence and the Sacred, trans. Patrick Gregory (Baltimore, M.D.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977), 4. 45Girard, Violence, 13. 46Girard, Violence, 12-13. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 226 Susan R. Bowers alludes to her in most of his female characters: "her mouth crueller than a tiger's, colder than a snake's, and beautiful beyond a woman's."47 Because the romantics see Medusa through her representations in visual art (the Uffizi Head of Medusa is the stimulus for most of their poetry about her) and then use their own art to interpret her for themselves, art itself then becomes, like Perseus's shield, the protection from her dangerous power. Whereas Shelley sees the imagination as a way to approach and find truth, for Rossetti it becomes almost a protection from the truth.48 Because these writers, however, became aware of Medusa through her representations in art, not myth, her femaleness was distanced for them; and thus the full force of her feminine erotic power was blunted. She has been treated in many ways much like most women in patriarchal art: "She is individualized no more than the hapless women captured as prizes in the Iliad; they are traded from one man to the next with only the briefest reference to their own emotions or desires.' '49 But modern male artists offer continuing testimony to the enormity of Medusa's original erotic force. A Medusa figure appears in William Butler Yeats's play At the Hawk's Well (1916) in the figure of the Hawk Woman who guards the well which "contains the treasure hard to attain . . .the source of eternal inspiration."50 Cuchulain, the legendary Irish hero whose opponents included the Morrigan, a powerful chthonic haggoddess who greatly resembled Medusa, is presented by Yeats as first trying to subdue the Hawk Woman but eventually becoming her votary. Yeats's Hawk Woman may have several sources; Jungian scholar Bettina Knapp sees Medusa as one of the most important. Such power does this Hawk Woman wield that anyone who gazes into her "unmoistened"eyes is cursed.Just as Medusain Greek mythologywho had serpents for hair, brazen claws, and enormous teeth-turned the beholder into stone-the Hawk Woman's personality is wholly destructive. Perseus was saved from annihilation because he carried a mirror with him and did not look directly at her. Psychologically no one may peer into a God's domain: the Self. To experience the absolute, either in its horrific or beauteous aspects, is to invite the destruction of the ego, to welcome its fragmentation.5' 47Algernon Charles Swinburne, Essays and Studies (London: Chatto and Windus, 191 1), 320. 48Kent Patterson, "A Terrible Beauty: Medusa in Three Victorian Poets," Tenlniessee Studies in Literature 17 (1972): 115. 49Patterson, "A Terrible Beauty," 112. 50Bettina L. Knapp, A Jungian Approach to Literature (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), 227. 51Knapp, A Jungian Approach, 258. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 227 Given Medusa's pre-Olympian status as goddess of the universe, Yeats's Medusa is terrifying because she represents the absolute. As Knapp points out, to look into her eyes is "to allow the collective unconscious to take over" and to drown in insanity.52 In contrast Robert Lowell's Medusa is the object of more ambivalence. His poem "Near the Ocean" focuses on the slaying of Medusa, but "The language of 'The last heartthrob / thrills through her flesh' suggests that the primary context is erotic; death equals orgasm, and a mutual sadomasochistic fulfillment is involved." Medusa appears in Lowell's poem as the strong mother. "The symbolic killing of this mother leads to compulsive sexual repetition, a search for new mothers."53 She is the female sexual object, the dreaded but longed for object of oedipal desire, and she dominates the protagonist's adult sexuality. The poem projects male failure onto the mother, made monstrous by male desire and, in turn, desired because she is monstrous. He can neither live with her nor without her: "And if she's killed his treadmill heart will never rest.' The severed radiance filters back, athirst for nightlife-gorgon head, fished up from the Aegean dead, with all its stranded snakes uncoiled, here beheaded and despoiled.54 In another poem about Medusa, Horace Gregory's "Medusa in Gramercy Park," a man invades a woman's apartment and finds her standing disheveled in a stream of sunlight "like Medusa / Before the curse fell on her, brilliant, white, / Heavy-limbed and still; clear-eyed, she seemed to wait. / The room stood still."55 Gregory assumes the Olympian version of Medusa but of the young girl before she is raped by Poseidon and acquires her powerful gaze. "Before the curse," she seems the perfect female object: "heavy-limbed and still," a passive, waiting figure frozen in time. Gregory's passive Medusa figure contrasts greatly with the pre-Olympian Medusa, that symbol of female wisdom and power who derives part of her power from her association with female biology. The earlier Medusa was both the powerful Mother, possessor of a dark female wisdom, and the beautiful young girl who would become Aphrodite in 52Knapp, A Jungian Approach, 258. 51Allan Williamson, Pity the Monsters: The Political Vision of Robert Lowell (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1974), 145. 54Robert Lowell, "Near the Ocean," in NVearthe Ocean (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1967), 42-47. 55Horace Gregory, "Medusa in Gramercy Park," in Medusa in Gramercy Park (New York: Macmillan, 1961), 123. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 228 Susan R. Bowers Greek myth. In her, female eros and female wisdom were joined, since the gynocentric goddesses were far more complex than their pale GrecoRoman imitations. Throughout her patriarchal history, however, Medusa kept her goddess qualities although these qualities became superimposed with male projection and objectification. Thus Poseidon's rape can be recognized as distortion and violation of Medusa's erotic power. When Athena, guardian of rationality, punishes the victim of the rape by changing her into a gorgon, she further objectifies that distortion. In a preliminary study of poems about Medusa by both male and female poets, Annis Pratt suggests that "the poems by women move to an identification with Medusa while the men . . . remain separated from her, at a distance."56 Although Medusa has become an object of fear and loathing for male artists, women have come to identify with her. Several women poets, for example, have identified with Medusa's victimization. Ann Stanford's poem "Medusa" intimately presents a woman's identification with the violation of Medusa's erotic power and the aftermath of repression which it created. In Stanford's poem, Medusa speaks in the first person of being raped by Poseidon: It is no great thing to a god. For me it was angerno consent on my part, no wooing, all harsh rough as a field hand. I didn't like it. My hair coiled in fury; my mind held hate alone. I thought of revenge, began to live on it. My hair turned to serpents, my eyes saw the world in stone.57 Stanford's Medusa loses the freshness of her own vision. In her rage and pain, all she can see is wasteland: "My furious glance destroyed all live things there," and she becomes alienated from the world by the "fury that I did not choose." Stanford shows us how female subjectivity, the creative female vision, can be destroyed by the forced obsession of anger, how the female gaze can be deadened by oppression. Edith Sitwell also identified with Medusa as rape victim. Sitwell's "Medusa Love Song" has a bitter vision of romantic love. She sees Medusa as an unsuspecting Aphrodite figure, innocent of the ways of men. Sitwell's Medusa remembers spring and being in love. 56Pratt, " 'Aunt Jennifer's Tigers,' " 132-33. 57Ann Stanford, "Medusa," in In Mediterranean Air (New York: Viking Press, 1977), 42. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 229 And I with the other amaryllideous girls of burning Gold walked under the boughs and listened to the sweet chattering Procne, and love began in the heart like the first wild spark in the almond Tree.58 Sitwell's Aphrodite-Medusa unwittingly hears even in her springtime paradise the warning of the violation soon to come, for Procne in Greek mythology was an avenging sister of a rape victim. After Procne's own husband had raped her sister Philomela, Procne took revenge by killing her own son and serving up his flesh to her husband. Procne and Philomela were then transformed into a swallow and a nightingale, respectively. As the nightingale, Philomela has become a personification of poetry. Sitwell's poem presents Medusa as an innocent victim inspired to love by her sister's song, which tells of the rape and violation Medusa is soon to experience. Sitwell's Medusa has the beauty and freshness of Aphrodite but lacks the prescience and power of the pre-Olympian goddess. The story of Medusa can also be analyzed as a deflection of female erotic power. As Audre Lorde suggests: the erotic is "a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling." Women empowered with the erotic, which is "born of chaos," are dangerous. By pruning the erotic to mere sensation, enemies of women radically diminish female power because they rob them of their psychic and emotional being.59 And the shield which Perseus uses to reflect Medusa's face, in order to kill her, is an example of this deflection of female erotic power. It is not then a big step from deflected, reflected eros to women serving as mirrors for men. But creativity cannot be directly associated with Medusa in the Greco-Roman myth; it can only emerge from her blood at the moment of her death as the winged horse Pegasus, who created the famous Spring of the Muses on Mt. Helicon. The focus on Medusa as victim, although a meaningful identification for many women, cannot acknowledge the dark power she embodies. Many contemporary women, however, are now discovering that "The 58Edith Sitwell, "Medusa's Love Song," in The Collected Poems of Edith Situwell(New York: Vanguard Press, 1954), 341. 59Lorde, Sister Outsider, 53, 55. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 230 Susan R. Bowers Medusa is a strong mythological image of the powerful woman.' '60 Feminist psychoanalysts have found that women who dream of themselves as Medusa often see their dreams as "expressing the need to find the source of [their] own creative energy."'6' But it is crucial to recognize that the psychological reclamation of Medusa within Everywoman is a dangerous process for it requires a descent into the subconscious and produces a "seeing [that] is radical and dangerously innovative . . . for it shears us of our defenses and entails a sacrifice of easy collective understandings and the hopes and expectations of looking good and safely belonging."62 This is the female gaze: Medusa's eyes, like those of the Sumerian goddess, see with an immediate"is-ness" that finds pretense, ideals, individuality and relatedness, irrelevant . . . They perceive with an objectivity like that of nature itself and our dreams. They bore into the soul to find the naked truth, to see reality beneath all its myriad forms and the illusions and defenses it displays.63 Is it any wonder that the patriarchy would seek to suppress the Medusa gaze? Women writers who have recognized the dark power of Medusa's gaze have differed from their male counterparts such as Yeats in that they have transformed their fear into power as they identified with Medusa. Louise Bogan and May Sarton, two of the twentieth-century women poets who have turned to mythological figures, traditionally viewed as demonic, as a rebellion against the stereotype of the creative woman as "unfeminine," exemplify this transformation. Mary DeShazer further elaborates that: "As the individual seeking wholeness struggles with a shadow figure, so [does] the poet confronting these projections of the 'Terrible Mother,' transforming them from negative, demonic forces to positive, balanced figures."64 Although I agree that poets such as Bogan and Sarton achieve a metamorphosis in their confrontations with the demonic energy of figures like Medusa, they do not transform them into "positive, balanced fig60Carol Schreier Rupprecht, "The Common Language of Women's Dreams: Colloquy of Mind and Body," Feminist Archetypal Theory:InterdisciplinaryRe-Visionsof Jungian Thought ed. Estella Lauter and Carol S. Rupprecht (Knoxville: University of T'ennessee Press, 1985), 213. 6'Estella Lauter and Carol Schreier Rupprecht, "Feminist Archetypal Theory: A Proposal," in Feminist Archetypal Theory, 232. 62Sylvia Brinton Perera, "The Descent of Inanna: Myth and Therapy," in Feminist Archetypal Theory, 157. 63Perera, "The Descent of Inanna," 156. 64Mary DeShazer, Inspiring Women: Reimagining the Muse (New York: Pergamon Press, 1986), 35-36. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 231 ures." Eros is born of chaos; the creative energy comes fiery from its demonic origins. It is true, however, as DeShazer points out, that the encounter with Medusa for these female poets is empowering rather than debilitating, even though it begins in terror.65 Thus in Bogan's 1923 poem, "Medusa," for example, the poet discovers . . .the bare eyes were before me And the hissing hair, Held up at a window, seen through a door. The stiff bald eyes, the serpents on the forehead Formed in the air.66 Bogan encounters Medusa in the instant of poetic inspiration, the experience of being possessed totally by Eros so that no other reality can be presented but the creative moment. This is the very instant which Yeats's Cuchulain, although in search of eternal inspiration, fears because, as noted earlier, the experience of the absolute is an invitation for the destruction of the ego. Bogan's poem does not disregard that danger; she gives Eros its due. She is "saying that art is fearful as well as beautiful; it is the Gorgon's head that can forever fix an evanescent landscape."67 But she emerges from the experience victorious. Instead of Eros-the unconscious, the absolute-being kept at a distance, separate from her, she acknowledges its presence within her as her own power. The lesson she learns is the lesson of female Eros: it offers fresh energy and revelation to those who can move past their fear of its danger. In Bogan's poem the preservation of the exquisite moment that art enables is the reward of the poet's courage: "The end will never brighten it more than this / Nor the rain blur." Bogan presents the poet's presence as finally ethereal in the world which her song has made. And I shall stand here like a shadow Under the great balanced day, My eyes on the yellow dust, that was lifting in the wind, And does not drift away.68 Thus for Bogan, the Medusa within her is a divine sculptor who succeeds in arresting beauty-the gentle and active side of the petrification that male viewers experienced or feared from her. Bogan's poem also reveals something about the female gaze. It does not seek to possess as does the male gaze, but lives and lets live. 65DeShazer, Inspiring Women, 202. 66Louise Bogan, "Medusa," in Blue Estuaries: Poemns,1923-1968 (New York: Ecco Press, 1977), 4. 67Malcolm Cowley, "Review of Poems and Ne,w Poems," in Critical Essays onlLouise Bogan, ed. Martha Collins (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1984), 58. 68Bogan, "Medusa," 4. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 232 Susan R. Bowers Other critics consider Medusa "the dominating image" in Bogan's work.69 Theodore Roethke, Bogan's close friend and fellow poet, considered Bogan's "Medusa" as "a breakthrough to great poetry, the whole piece welling up from the unconscious." He reads the Medusa in this poem as "the image of the powerful, enigmatic mother," possibly derived from Bogan's own mother.70 Roethke's sense of the origins of the poem agrees with the idea of Medusa as a crucial force within the female unconscious. Medusa is indeed evoked here and elsewhere as a powerful mother figure. But, as we have seen, she is that and more. As DeShazer's work on the muse for women poets makes clear, May Sarton's work demonstrates how Medusa and Aphrodite are linked; for example, she points to Sarton's apostrophe to Aphrodite in "These Images Remain" as an example of how "the poet confronts the sexual tension at the heart of the poet-muse relationship. As the epitome of female beauty and eroticism, Aphrodite inspires the poet to become free and fertile."'7' Sarton begins by comparing herself to Aphrodite on her shell, newly emerged from the sea. Wrapped in the wind, the net of nerves undone, So piercingly alive and beautiful, Her breasts are eyes. She opens in the sun And sees herself reflected in the sand When the great wave has left her naked there, And looks at her own feet and on her golden hair As on some treasure given by the seas To one who holds the earth between her knees.72 In Sarton's poem, Medusa's eyes become Aphrodite's breasts: what is about death in the Greco-Roman myth transformed into that which is life-giving. Instead of being reflected in Perseus's shield, like Medusa, and thus deflected, Aphrodite is reflected in the sand; instead of enabling her murder, her reflection permits Aphrodite to marvel at her own beauty "as on some treasure." Finally, Aphrodite is portrayed as source of the earth: "one who holds the earth between her knees." Sarton not only re-unites Medusa with Aphrodite but recognizes herself as poet, as an Aphrodite-"You are free to stand like Aphrodite on her shell"just as she recognizes Medusa in herself and herself in Medusa. Sarton 69See, for example, Sister Angela, [Veronica B. O'Reilly], as quoted in Jacqueline Ridgeway, Louise Bogan (Boston: Twayne Publications, 1984), 37. 70Theodore Roethke, "The Poetry of Louise Bogan," in Critical Essays on Louise Bogan, n. 72, 89. 7'DeShazer, Inspiring Women, 122. 72May Sarton, "These Images Remain," in CollectedPoems (New York: Norton, 1974), 144-47. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 233 illustrates this in "The Muse as Medusa," when, after the initial terror of confronting Medusa, I turn your face around! It is my face. That frozen rage is what I must exploreOh secret, self-enclosed, and ravaged place! This is the gift I thank Medusa for.7" Self-enclosed, creative power turns into frozen rage secreted in the most hidden recesses of the female soul. To acknowledge it as gift is to release it into the light of day, to free one's creativity. Like Sarton, women achieve greater creativity by braving the encounter with their own creative power, their own Medusa. Sarton presents the female artist as willingly vulnerable to Medusa's intense power and thus thoroughly changed by it: I came as naked as any little fish, Prepared to be hooked, gutted, caught; But I saw you, Medusa, made my wish, And when I left you I was clothed in thought . . .74 By refusing to regard the Medusa at a safe distance or through its reflection, Sarton enables a radical transformation of both the Medusa head and herself which ultimately gives birth to the poetic gesture. Sarton's remarkable equation of Medusa and Aphrodite achieves three things: first, she reminds us of Medusa, the beautiful young girl who was raped; second, she reunites Medusa's extraordinary power with Aphrodite's freshness and beauty; third and most importantly, she succeeds in radically revising a symbol of justification for female oppression, the fearsome seductress, into a female-identified, female-empowering figure. Sarton's achievement exemplifies the power of the goddess Medusa and the female Eros that she represents. As Sylvia Brinton Perera points out, Medusa's blood can kill or heal depending on the attitude taken toward her.75 In the early years of the women's movement, Medusa, in Paula Bennett's words, "became the passionate symbol for the woman poet's liberated self": In taking Medusa for their muse, women poets of the past two decades are owning themselves, that is, they are owning those aspects of their being that their families and society have invalidated by treating such qualities as unfeminine and unacceptable. And in repossessing these 75Sarton, "The 74Sarton, "The 75Perera, "The eshkigal, Medusa's of Persephone. Muse as Medusa," in Collected Poems, 332. Muse as Medusa," 332. Descent of Inanna," 176. Perera's comments specifically address ErSumerian counterpart in many respects. Ereshkigal is also a counterpart This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 234 SusanR. Bowers aspects of themselves they are repossessing the creative as well as the destructive energies to which they give rise.76 Contemporary women artists who embrace Medusa with full awareness of her dark power exhibit a fierce integrity and free expression of female eros. Elana Dykewoman, for example, uses a drawing of a ritual mask of Medusa on the cover of her collection of lesbian stories and poems, They Will Know Me by My Teeth. These poets understand the other side of the female gaze. It is not only Medusa's gaze but also the gaze upon Medusa into the face of anger, darkness, and power. Thus Rachel Blau DuPlessis's Medusa poem is the story of a woman "unbury[ing]" and "re-member[ing]" herself by confronting and acknowledging the darkness within her.77 Such women echo the female Eros that is Medusa, the wild, free force that ultimately enables the rediscovery of female creativity and the ability for women to think of themselves alone. The issue for women . . . is getting power, which is only attained by using it . . . To think of one's self alone, not in a specular relationship as the mirror to man's identity, is to enter the "dark continent" of women; it is to begin a new process of self-definition, by attempting to refuse the role of Other to his absolute one.78 For women artists to transform Medusa from what she has been deemed by males into Aphrodite/Medusa, the embodiment of female Eros with which women can identify, is to re-possess themselves, to liberate their bodies and their minds from the patriarchy. the moment of desire (the moment when the writer most clearly installs herself in her writing) becomes a refusal of mastery, an opting for openness and possibility, which can in itself make women's writing a challenge to the literary structures it must necessarily inhabit.79 What Medusa has represented to women is an image of the hatred and fear of female power that, as long as women themselves could not claim that power, allowed the "best" poetry to be, as Poe claimed, about the death of beautiful women. A definition of matriarchal art declares it to be art which "shows the erotic to be the strongest creative force as opposed to devaluing and suppressing it as the ascetic and patriarchal 76Paula Bennett, My Life a Loaded Gun: Female Creativity and Ferinnist Poetics (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986), 245. 77Rachel Blau DePlessis, "Medusa," in Wells (New York: Montemora Press, 1980), 13-22. 78Elizabeth A. Meese, Crossing the Double-Cross:The Practice of Feminist Criticisn (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 123. 79MaryJacobus, "The Difference in View," in Women Writing and Writing about Women, ed. Mary Jacobus (London: Croom Helm with Oxford University Women's Studies Committee, 1979), 16. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Medusa and the Female Gaze 235 religions and moral systems have done."80 Such is the art inspired in women by Medusa. In it, with the courage of poets such as Bogan and Sarton, Medusa becomes again what she was once for women, an electrifying force representing the dynamic power of the female gaze. The journey of Medusa in Western culture is a journey from the mutilation and destruction ofethe female body in Greco-Roman myth to the celebration of the whole female self. The Medusa of the female imagination is whole, and as Helene Cixous declares, "She is beautiful and she is laughing.' '81 80Heide Gottner-Abendroth, "Nine Principles of a Matriarchal Aesthetic," in Feminist Aesthetics, ed. Gisela Ecker (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986), 93. 81H6lene Cixous, "The Laugh of the Medusa," trans. Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen, Signs 1 (Summer 1976): 885. This content downloaded from 130.237.165.40 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 11:40:30 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions