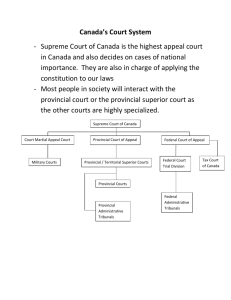

CHAPTER 2 THE CANADIAN LEGAL SYSTEM: AN OVERVIEW Chapter Objectives 2.1 Differentiate between an inquisitorial and an adversarial legal system. 2.2 Explain the division of legislative powers between the federal and provincial governments. 2.3 Describe the four sources of law in Canada. 2.4 Describe the levels within the Canadian court structure. 2.5 Compare and contrast the criminal and civil court processes. 2.6 Outline the key elements of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. 2.7 Explain the elements of a criminal offence, list the types of criminal offences, and describe the defences used. Forensic psychologists work at the intersection of psychology and law. Each other chapter in this textbook describes a component of this fascinating discipline. This chapter is somewhat different; it provides a very brief description of the Canadian legal system. We begin with the big picture; a description of Canada’s legal system and an explanation of why the federal government passes laws in some areas and the provincial governments pass laws in other areas. This will help students to understand the sources of Canadian law and the Canadian court structure. Of particular importance is the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms because it places principled limits on the substance, interpretation, and application of law. With this framework in place, we describe criminal offences, what they are, how they are prosecuted, and available defenses. Prosecuting and defending against a criminal offence almost always involves the presentation of evidence. In the last section of this chapter we describe different kinds of evidence, with a particular emphasis on opinion/expert evidence. c02.indd 29 9/13/2013 8:12:09 PM 30 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview Legal Systems Learning Objective 2.1 Differentiate between an inquisitorial and an adversarial legal system. inquisitorial legal system a legal system in which the law is codified (i.e., written down), judges play an active role in the proceedings, experts are called by the court, and the lawyers’ role is, in part, to assist the court; it is used in many European countries adversarial legal system a legal system in which two sides—the defence representing the accused versus the prosecution (Crown) representing the people—present their position before an impartial judge or jury, who attempt to determine the truth of the case; it is used in North America To better understand the North American legal system, we begin by briefly contrasting two distinct systems of law introduced in Chapter 1: the inquisitorial system and the adversarial system. The inquisitorial legal system is used in many European countries. In this system, the law is typically codified; that is, it is written down systematically as a set of principles or rules. Judges play an active role at trial in terms of directing the trial, as well as calling and questioning witnesses. Typically, experts are appointed by the court rather than being appointed by one side in the dispute. A lawyer’s role is as much to assist the court as it is to represent the client’s interest. Generally, the adversarial legal system is based in common law. This means that the law is written in past court decisions. The lawyers present evidence and examine witnesses, while the judge’s role is to be the final arbitrator, listening to the evidence as presented by the parties. In an adversarial system, the role of a defense lawyer is to be an advocate for the client and to vigorously defend the clients to the full extent permitted by law. Typically, expert witnesses are appointed by one party in the dispute. For pedagogical reasons, we have described the two systems as if they are distinct from one another. In practice, legal systems often have both adversarial and inquisitorial elements but are more strongly associated with one system or the other. For instance, the Canadian legal system is described as adversarial, but much of our law is codified (written down) in legislation. Some research has been done on public perceptions of legal structures. Anderson and Otto (2003) studied participants who were familiar with the adversarial system in the United States and participants in the Netherlands, a country that has an inquisitorial system. They found that participants saw the adversarial system as more fair in terms of the presentation of all relevant evidence to the judge and in terms of parties being given a full opportunity to present their case. On all other measures, participants tended to prefer their own legal system. Research on expert testimony found that court appointments (as in inquisitorial systems) may help to ensure that experts present unbiased testimony (Merckelbach, 2003) and may have a positive effect on the perceived credibility of the experts (Cooper & Hall, 2000) compared to experts commissioned by one party to the proceeding (as in adversarial systems). Division of Powers Learning Objective 2.2 Explain the division of legislative powers between the federal and provincial governments. c02.indd 30 In 1867, Canada was established under the British North America Act (BNA Act). In 1982 when the Constitution was repatriated to Canada, the BNA Act was renamed the Constitution Act, 1867 and the Constitution Act, 1982 came into force. The Constitution Act, 1982 contains the Constitution Act, 1867 and new acts/amendments that were passed between 1867 and 1982. In the Constitution Act, 1867, powers to pass laws in Canada were divided such that the provinces were given 9/13/2013 8:12:09 PM Sources of Law 31 INSIGHT 2.1 Division of Powers: Provincial Jurisdiction over Mental Health Law Section 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867, gives jurisdiction over metal health law to the provinces. Under this authority, each province has enacted mental health legislation, including a provision for treating involuntarily committed patients. In British Columbia, the legislation specifically allows psychiatric institutions to treat involuntarily committed patients against their will. In Ontario, involuntarily committed patients may not be treated against their will except in very particular circumstances. In New Brunswick, involuntarily committed patients may refuse to be treated, but that decision may be overruled by a review board. In Quebec, a judicial order is required to treat involuntarily committed persons who refused treatment, and the order will only be given in the most extraordinary circumstances. jurisdiction over some areas (generally, areas that are of local concern) and the federal government was given the power to pass laws in other areas (generally, areas that are of national concern). Importantly, this is a true division of powers. It is not the case that power over all important areas was given to one level of government and the other level was given everything else (residual power). This means that if the federal government attempts to pass a law in an area that is the exclusive domain of the provinces, the federal law will be struck down as “ultra vires”—outside the jurisdiction of the body that passed the law. Similarly, if a provincial government tries to pass a law in an area that is in the jurisdiction of the federal government, it will be struck down. This division of powers is described in sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Section 91 enumerates federal powers and section 92 enumerates provincial powers. Each enumerated item, or power, is called a “head of power.” Understanding this is important because it explains why some laws are written in federal legislation and other laws are written in provincial legislation. It also explains why some laws are common across Canada while others are unique to provinces. For now, you should know that jurisdiction over the enactment of criminal law resides with the federal government (i.e., in section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867 ), while jurisdiction over prosecuting and enforcing criminal law (e.g., police, provincial corrections, etc.) as well as most areas of civil law, including personal injury law and mental health law, are in provincial jurisdiction (i.e., in section 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867; see Insight 2.1). Sources of Law In this section we describe four sources of law: the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, legislation (either federal or provincial), common law, and administrative law. Learning Objective 2.3 Describe the four sources of law in Canada. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms The Constitution Act, 1982, including the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter), is the supreme law of Canada and, generally, cannot be overridden by statute law or common law. There are a few exceptions: the Charter can be c02.indd 31 9/13/2013 8:12:09 PM 32 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview overridden when an infringement can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society or if the notwithstanding clause is invoked. As with all written law, the Charter requires interpretation by the judiciary. For example, section 11(b) of the Charter provides that a person charged with an offence has the right to be tried within a reasonable time. What is an offence? What is a reasonable period of time? These concepts must be interpreted by judges. Interpretable language was purposely used in the text of the Charter, in part, to reduce the likelihood that the Charter would become stagnant, reflecting values and principles applicable in 1982 but, perhaps, not in 1999 or 2014. We will discuss the Charter more thoroughly later in this chapter. Legislation Although Canada is a common-law country, much of our law is written in legislation (federal or provincial). This does not mean that the law, as written in legislation, is clear and easily applied; most legislation cannot be applied without further interpretation, typically by judges. This is not an accident or the result of sloppy writing. It is impossible to anticipate and articulate each circumstance that may trigger the legislation or to give explicit directions on how to proceed, so the purpose of legislation is to provide guidelines that should be particular enough to allow a judge to apply them reasonably to a set of facts. Common Law Law that derives from previously decided cases is called common law. Generally, you will not find these laws written in legislation. Rather, their definitions and applications can be found in previously decided cases (see Insight 2.2). Administrative Law The federal or provincial governments may delegate powers to administrative tribunals to interpret and enforce laws in some areas. The actual laws are passed INSIGHT 2.2 Hearsay: An Example of Common Law Any out-of-court statement that is tendered to prove the truth of its contents is hearsay. There are two essential elements to this definition. First, the speaker is not in court and the statement is to be reported by someone who only heard it. Second, the side wanting to present the statement would like the trier of fact to accept it as true. For instance, you are asked to take the stand to say that Helen called you Friday to say “It’s raining in England.” If your evidence is being tendered to prove that it was raining in c02.indd 32 England, it is hearsay. If your evidence is being tendered to prove that you spoke to Helen on Friday and she was alive then, it is not hearsay and will not trigger the hearsay rules. Hearsay is presumptively inadmissible because, absent evidence to the contrary, it is considered to be unreliable. To be presumptively inadmissible means that unless the evidence can pass a certain test, it will not be allowed. The test that must be passed to admit hearsay evidence is that the hearsay evidence is both necessary and reliable (R. v. Khan, 1990). 9/13/2013 8:12:09 PM Canadian Court Structure 33 by the body with authority to do so (that is, the federal or provincial government), but the power to interpret and enforce the laws may be conferred on administrative bodies through legislation. This legislation outlines the boundaries of the administrative tribunal’s authority. Importantly, administrative tribunals are bound by applicable constitutional law, statute law, and common law, just like any other body with authority to compel behaviour and pass sanctions. Administrative tribunals deal with issues such as allegations of breaches of human rights, employment standards, immigration, parole, and some mental health issues. Canadian Court Structure In this section we discuss four levels of courts, starting with the lowest level of court and moving to the highest level—provincial courts, provincial superior courts, provincial courts of appeal, and the Supreme Court of Canada.1 As can be seen in Figure 2.1, this is not a comprehensive discussion of the Canadian court system; however, it outlines the court levels that are most relevant to our discussion. We also introduce the doctrine of stare decisis (Latin for “Let the decision stand”). This doctrine states that judges are bound to decide like cases alike. Not surprisingly, there can be a lot of debate about whether a particular case is “like” a previous case, but that is beyond the scope of this discussion. Let’s imagine for now that “like cases” can be identified. The doctrine of stare decisis is important because it provides a measure of predictability and certainty in the law. If you know the outcome of a previous case and it is like a pending case, you can predict, with some degree of certainty, the outcome of the pending case. Importantly, not all court decisions are binding on all other courts. If that were the case there would be no functional appeal process (the appeal court would be bound by the decision of the trial court) and the law would be stagnant (it could not change a bad law or respond to changing social values). Learning Objective 2.4 Describe the levels within the Canadian court structure. stare decisis a term meaning “let the decision stand.” The doctrine of stare decisis states that judges are bound to decide like cases alike Provincial Courts Provincial courts are trial courts presided over by provincially appointed judges. They hear most criminal cases, about half of the family cases (e.g., those involving neglected/abused children, adoption, and division of property), almost all youth cases, and civil cases that involve small amounts of money. When a trial is heard in a provincial court, there is no option to be tried by a jury. Decisions are not binding on other provincial court judges or on any other court. Although not binding, decisions of other judges at the same court level are persuasive, and like cases should be decided alike unless compelling arguments to do otherwise are accepted. 1 c02.indd 33 In this chapter, “provinces” refers to “territories” also and “provincial” also refers to “territorial.” 9/13/2013 8:12:09 PM 34 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview Supreme Court of Canada Court Martial Appeal Court Provincial/Territorial Courts of Appeal Provincial/Territorial Superior Courts Militarty Courts Federal Court of Appeal Federal Court Tax Court of Canada Provincial/Territorial Courts Provincial Administrative Tribunals Federal Administrative Tribunals Figure 2.1 Outline of Canada’s court system Note: Northwest Territories and Yukon have the same court structure as each of the provinces but the courts are called territorial courts rather than provincial courts. In Nunavut, there is no territorial court; matters that would normally be heard at this level are heard by the Nunavut Court of Justice, which is a superior court. The Nunavut Court of Justice combines the power of the superior trial court and the territorial court so that the same judge can hear all cases that arise in the territory. Source: Justice Canada, 2013, www.justice. gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/ccs-ajc/page3.html. Reproduced with permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2013. Provincial Superior Courts Provincial superior courts are trial courts presided over by federally appointed justices. They hear some criminal and civil cases, applications for divorce, and appeals from provincial courts on matters of small claims, family cases, and less serious criminal matters (e.g., summary convictions, which are defined in the “Criminal Offences” section). For cases heard in provincial superior court, accused persons may elect trial by judge alone or trial by judge and jury if they may be subject to a prison term of five years or more. Decisions are binding on provincial courts in that province and are persuasive for other superior court judges in the same province as well as for courts in other provinces. Provincial Courts of Appeal Provincial courts of appeal hear civil and criminal appeals. They are appeal courts, not a trial courts. That is, they do not hear from witnesses, and, c02.indd 34 9/13/2013 8:12:09 PM Canadian Court Structure 35 ordinarily, evidence that was not presented at trial cannot be raised on appeal. These courts are presided over by federally appointed justices in groups (panels) of three or five justices. The fi nal decision of the court is the judgment of the majority; a unanimous decision is not needed. Parties who wish to appeal to the provincial court of appeal must apply to do so. The court may agree or decline to hear the appeal. This is not a decision on the merits of the case. Instead, it is the initial decision as to whether an appeal will be heard. The Crown or the defence can apply to appeal a sentence. The Crown may apply to appeal a verdict (the Crown would only apply to appeal an acquittal, of course) on a question of law. The accused may apply to appeal the verdict (the accused would only apply to appeal a conviction, of course) on a question of law, fact, or mixed law and fact. Note that in Canada the Crown can sometimes apply to appeal an acquittal. Some of you will recall the O. J. Simpson murder trial. Many Americans thought Simpson was guilty of murdering his ex-wife and her boyfriend, but he was acquitted at trial. When the acquittal was announced, all criminal proceedings were complete because, in the United States, the prosecution cannot appeal an acquittal. In Canada, as long as there is an appealable question of law, the Crown can apply to appeal an acquittal. What are questions of law, fact, and mixed law and fact? This is best answered with an example. Suppose it is a crime to be too tall. A question of law is, “How tall must a person be to be too tall?” Let’s say the answer is six feet tall. A question of fact is, “How tall is the defendant?” Let’s say in this case the man is five foot eleven. A question of mixed law and fact is, “Is this man so tall that he has committed an offence?” In this example, the answer would be “no.” Decisions of provincial courts of appeal are binding on superior courts and provincial courts in that province, and they are persuasive on courts in other provinces that have the same law. Supreme Court of Canada Appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada (Figure 2.2) must have been heard in a provincial court of appeal first. Parties who wish to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada must first apply to do so; the Court may agree or decline to hear the appeal. On questions of law, either the accused or the Crown may appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. Appeals are heard by a panel of five, seven, or nine justices. The decision of the court does not have to be unanimous. The majority judgment is binding. Decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada are binding on all inferior courts that are subject to the law under appeal. Recall that some laws are under provincial jurisdiction (listed in s. 92 of the Constitution Act), so only the provinces that have enacted the same law are bound by a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada that addressed the law. For instance, in Starson c02.indd 35 9/13/2013 8:12:09 PM 36 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview Figure 2.2 Members of the Supreme Court of Canada Back row from left: Madam Justice Andromache Karakatsanis, Mr. Justice Thomas A. Cromwell, Mr. Justice Michael J. Moldaver, and Mr. Justice Richard Wagner; front row from left, Madam Justice Rosalie Silberman Abella, Mr. Justice Louis LeBel, the Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, P.C. Chief Justice of Canada, Mr. Justice Morris J. Fish, and Mr. Justice Marshall Rothstein. Ottawa, December 3, 2012. (Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press) v. Swayze (2003) the Supreme Court of Canada held that, in the circumstances and given the law that applied in Ontario at the time, Starson could not be treated for his mental illness against his will. Starson had been accused of uttering death threats. He was involuntarily committed to a forensic psychiatric hospital after he was found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder. That judgment was not binding in British Columbia, because there is a provision in the BC Mental Health Act that allows for involuntary treatment of involuntarily committed patients. Decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada that relate to federally enacted laws (e.g., criminal law) are binding throughout Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada is not bound by its own decisions. The Court must be able to reverse its own decisions when it is appropriate to do so. When you read legal decisions, think about the court level that released the decision. If it is a Supreme Court of Canada decision, it is the law in all jurisdictions bound by that law. A provincial court of appeal decision is binding on trial courts in that province and persuasive on courts in other provinces. If you read a decision from a provincial superior court, generally it is binding on provincial courts in that province and persuasive in provinces bound by that law. For information on reading appeal decisions, see Insight 2.3. c02.indd 36 9/13/2013 8:12:10 PM The Court Process 37 INSIGHT 2.3 How to Read an Appeal Decision from the minority. Often, but not always, the majority decision is reported first. Fourth, identify clearly the issues that are the basis of the appeal. The court may split differently on the different issues. Consider an appeal panel with Justices A, B, C, D, and E in a case that involves two issues. On issue 1 (e.g., was there a Charter infringement?), the court may be split such that Justices C, D, and E conclude that there was a Charter infringement, and Justices A and B conclude that there was not. On issue 2 (e.g., is the infringement demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society?), Justices D and E may find that it is justified, and Justice C may find that it is not. Note that in this case, although three justices found a Charter infringement, the appeal would fail. To further complicate things, it is not unusual for two justices to come to the same conclusion for different reasons. For instance, a conclusion that the trial judge’s finding on credibility is patently unsupportable may be explained by some justices as a consequence of too many inconsistencies and by others as testimony that defies logic. If this happens, look for the reasons of the majority; this will be what binds lower courts. First, determine who is bringing the appeal and who is responding to the appeal. In a criminal case, if a person was convicted at trial and appeals the decision to the provincial court of appeal, the convicted person is the appellant and the Crown is the respondent. If the appellant (the convicted person in this example) wins the appeal, and if the Crown appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada, the convicted person becomes the respondent and the Crown becomes the appellant. In a civil court trial, the person bringing the action is the plaintiff and the person responding to the action is the defendant. If the plaintiff loses at trial and appeals the decision to the provincial court of appeal, the original plaintiff becomes the appellant and the original defendant is the respondent. If the trial decision is overturned at the provincial court of appeal, and if that decision is appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, the appellant at the Supreme Court of Canada is the original defendant and the respondent at the Supreme Court of Canada is the original plaintiff. As you can see, it can be very complicated, so it is best to figure out which party is which before you begin to read the decision. Second, read the headnote at the beginning of the case. This is like an abstract, but it is often much longer. Its role is the same: to summarize the case. Third, determine how many judges are sitting on appellant the party bringing an appeal the panel. You will need this information to know which decision is the majority decision and which decision came respondent the party responding to an appeal The Court Process Most cases that proceed in the criminal courts may also proceed in civil courts if personal loss is involved. Although not required, it is typically true that a case which may proceed both civilly and criminally will go to criminal court first. There are several important distinctions between civil and criminal processes (summarized in Table 2.1). The purpose of criminal law is to deal with the perpetrator, whereas the purpose of civil law is to restore the injured party to the pre-injury state. When a case proceeds criminally, the police investigate the allegation, the Crown brings the charge and prosecutes the case, and the State pays for the prosecution. Contrast this with a case that proceeds civilly, where the plaintiff investigates and hires a lawyer to commence the proceedings and to argue the case in court. (Although, as discussed in Chapter 4, it is becoming more common for people to represent themselves in court.) In both civil and c02.indd 37 Learning Objective 2.5 Compare and contrast the criminal and civil court processes. 9/13/2013 8:12:11 PM 38 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview Table 2.1 The Process of Proceeding Criminally and Civilly Criminal Civil Purpose Deal with the perpetrator Restore the injured party Who investigates? The police An individual Who brings the case to court? The Crown The plaintiff Who pays for the prosecution? The State The plaintiff Who pays for the defence? The defendant The defendant Who must prove the case? The Crown The plaintiff Standard of proof Beyond a reasonable doubt On a balance of probabilities Possible outcome Restriction of liberty Monetary award criminal proceedings, the defendant is responsible for the costs of the defence. In both processes, the burden is on the Crown (criminal) or the plaintiff (civil) to prove the allegation beyond a reasonable doubt (criminal burden) or on a balance of probabilities (civil burden). If the allegation is proved, the defendant will likely have some restrictions on liberty imposed (criminal) or be required to pay a monetary award (civil). The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Learning Objective 2.6 Outline the key elements of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. c02.indd 38 Besides criminal and civil law, psychologists and other social scientists may also be involved in human rights law. There are two broad sources of human rights protections in Canada: human rights codes and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Two important criteria are considered when determining which law applies: the identity of the alleged discriminator, and the nature of the discrimination. If the alleged discriminator is a government actor who is accused of infringing a fundamental right listed in the Charter (e.g., freedom of speech or unreasonable search and seizure), the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms may apply, and the case will likely be heard in a court of law. If the alleged discrimination involves one of the prohibited grounds listed in a human rights act (e.g., disability, race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, marital status), the case may be heard under the federal or a provincial human rights acts. Which one? If the alleged discriminator is under federal jurisdiction (e.g., a bank), the case may be heard under the Canadian Human Rights Act by a human rights tribunal. If the alleged discriminator is not under federal jurisdiction (e.g., a condominium association, a private business owner), the case may be heard under the applicable provincial human rights code by a human rights tribunal. Provincial and federal human rights acts are “mere” legislation and can be amended or revoked relatively easily (as can any piece of legislation). The Charter is “entrenched,” and although it is possible 9/13/2013 8:12:11 PM The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 39 to amend it, the amending formula is very complex and the process has not been undertaken since the Charter was enacted in 1982. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, being part of the Constitution Act, 1982, is the supreme law of Canada. Government actors cannot pass legislation that infringes our Charter rights, nor can government actors behave in a manner that infringes our Charter rights. There are three important elements to remember. First, the Charter protects us against unconstitutional actions of government actors. It does not protect us against the actions of non-government actors. So if your landlord discriminates against you, or if your employer discriminates against you (assuming your employer is not a government actor), you do not have a Charter argument. Because the Charter was intended, in large part, to protect individuals from potential abuses of State power, it is not surprising that much of the Charter deals with protection of persons accused of an offence—this is the group against whom the State has the potential to be most oppressive. There are two ways that Charter rights can be infringed: the law itself may infringe Charter rights, or the way the law was applied may infringe Charter rights (see Figures 2.3a and 2.3b). If a law is passed that infringes a Charter right (e.g., a law that allows the police to search without a warrant), s. 52 of the Charter allows a court to do one of three things. First, it may strike down the legislation in its entirety. For example, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the constructive murder provision in the Criminal Code as being contrary to ss. 7 and 11(d) of the Charter. Constructive murder meant a person was guilty of culpable murder if that person caused the death of another in the commission of a particular other offence, even if the person did not intend for death to occur. The Court held that it is contrary to both fundamental justice (s. 7) and the right to fair hearing (s. 11(d)) to fail to require the Crown to prove intent to kill (R. v. Vaillancourt, 1987). Second, a court may read down (rewrite/revise) the part of the legislation that is contrary to a Charter right. That may involve striking down or striking out that part of the legislation. For example, if a law is passed that requires police to have a warrant before entering a private residence except if the police suspect pornography has been produced in that location, the courts may strike out the part of the legislation that allows warrantless searches in those circumstances. Third, a court may read in elements that bring the legislation in line with the Charter. For example, if a law confers a benefit on single mothers but does not confer the same benefit on single fathers, the court may “read into” the legislation that the benefit is provided to all single parents (to strike it down would be a hardship to single mothers). Section 1 of the Charter allows legislators to pass a law that is contrary to Charter rights if it is a reasonable limit that can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. For example, some of our drinking and driving laws infringe Charter rights in that they deny the right to counsel when a person is detained at a roadside check for impaired drivers. However, the objective that the c02.indd 39 9/13/2013 8:12:11 PM 40 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview Strike down the law The law itself infringes Charter rights Read down the law to be consistent with the Charter The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it are subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic socitey (s.1). Read in elements to make the law consistent with the Charter Figure 2.3a Infringement of Charter rights: The law itself infringes Charter rights The way the law was applied infringes Charter rights Any remedy that is just and appropriate in the circumstances Evidence is inadmissible If, having regard to all the circumstances, the admission of it (the evidence) in the proceeding would bring the administration of justice into disrepute (s. 24(2)). Figure 2.3b Infringement of Charter rights: The way the law was applied infringes Charter rights laws are designed to achieve (i.e., reduce the harm that comes from impaired driving) is important and so can support a “relatively minor” Charter infringement. We just discussed what could happen if a law is passed that infringes a Charter right. It is also possible that a law is consistent with the Charter but is enforced or applied in a way that infringes a Charter right. For example, let’s say you were arrested, placed in a police car, read your right to a lawyer, and then questioned—all in the police car. In this case, the way the police officer administered the law (i.e., the right to counsel upon arrest or detention) was probably an infringement of your Charter s. 10 right because you were not given a reasonable opportunity to contact a lawyer. Let’s further assume that while you were in the police car, you said things that implicated you in a crime. Can the incriminating statements be used against you in court? Section 24 of the Charter allows the court to do one of two things. It may apply any remedy that is just and appropriate in the circumstances (e.g., stay the proceedings). Or the court may exclude any evidence that was obtained as a result of the Charter infringement if, “having regard to all the circumstances, the admission of it in the proceeding would bring the administration of justice into disrepute” (Charter s. 24(2)). As you will learn later in this course, the last part of s. 24 is very important, so we will repeat it: the court may exclude the evidence if “having regard to all the circumstances, the admission of it in the proceeding would bring the administration of justice into disrepute.” If admission of the evidence would not bring the administration of justice into disrepute, it may be admitted at trial. c02.indd 40 9/13/2013 8:12:11 PM Criminal Offences 41 The following are a few more Charter sections that you will read about in the following chapters. Section 7: “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” Section 8: “Everyone has the right to be secure against unreasonable search and seizure.” Section 10: “Everyone has the right, upon arrest or detention, to obtain and instruct counsel without delay and to be informed of that right.” Section 11: “A person charged with an offence has the right (a) to be informed without unreasonable delay of the specific offence; (b) to be tried within a reasonable time; (c) not to be compelled to be a witness in proceedings against the person in respect of the offence; (d) to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law in a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal; (e) not to be denied reasonable bail without just cause; (f ) except in the case of an offence under military law tried before a military tribunal, to the benefit of trial by jury where the maximum punishment for the offence is imprisonment for five years or a more severe punishment.” A few comments about sections 7 and 11(b) are warranted. The s. 7 right to fundamental justice has been interpreted to include the right to silence. The right to silence does not mean that if accused people testify at their trial, they may refuse to answer particular questions; it means that accused persons do not have to testify. It also does not mean that the police must stop questioning suspects when they invoke the right to silence. The police may continue to ask questions, and accused persons may continue to refuse to answer them. Under s. 11(b), the accused has a right to a trial within a reasonable period. The time begins when the charge is laid, not when the offence occurred. To calculate the time from when the offence occurred would be akin to imposing a limitations period on criminal offences. With very few exceptions (e.g., summary offences) there are no limitation periods on criminal offences in Canada. Learning Objective 2.7 Criminal Offences All criminal offences are listed in the Criminal Code of Canada (1985). Under each offence description, the elements of the offence are listed and the type of offence is c02.indd 41 Explain the elements of a criminal offence, list the types of criminal offences, and describe the defences used. 9/13/2013 8:12:11 PM 42 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview Summary Provincial Court (no jury) Provincial Court Indictable Hybrid Electable (discretion of Accused) Superior Court (judge alone or judge and jury) Provincial Court (judge alone) Superior Court (judge alone) Superior Court (judge and jury) Figure 2.4 Types of criminal offences articulated. (See Figure 2.4 for the different types of criminal offences.) Available defences are not listed in the Criminal Code, but they are described below. Elements of Criminal Offences actus reus the act that constitutes a criminal offence; Latin for “guilty act” mens rea the mental state of the perpetrator at the time of the offence; Latin for “guilty mind” c02.indd 42 There are at least two elements in most criminal offences; the actus reus and the mens rea. The actus reus is the act itself. Generally, in criminal law, the actus reus requires that the person committed a particular act. Occasionally, the actus reus is failure to do something that is required by law (e.g., failure to provide the necessities of life for your child). The mens rea is the mental state of the perpetrator at the time of the offence. This is not motive. A person can intend to commit a criminal offence without having a motive to do so. The specific mens rea that is needed to prove an offence will vary with the crime. For instance, the offence of firstdegree murder generally requires the Crown to prove that the accused planned and deliberated on the murder. There are exceptions to this—for instance, murder of a police officer is first degree whether or not the mens rea of planning and deliberation is proven. For the offence of second-degree murder, the mens rea the Crown must prove is that the accused intended to cause bodily harm, knew 9/13/2013 8:12:11 PM Criminal Offences 43 or ought to have known that death was likely, and recklessly disregarded whether death would ensue or not. For the offence of manslaughter, the Crown must prove that the actions of the defendant caused the death of the victim, and the mens rea of first-and second-degree murder cannot be proven. Types of Criminal Offences There are three types of criminal offences: summary, indictable, and hybrid. Each type is discussed below and illustrated in Figure 2.4. Summary Offences Summary offences are less serious offences that carry penalties of a fine of not more than $2,000 and/or a prison term of not more than six months. Generally, there is a six-month limitations period on summary offences. That is, a charge must be laid within six months of the date of the offence, unless the Crown and accused agree to extend this limit. Summary offences are heard in provincial court and cannot be heard by a jury. Examples of summary offences are vagrancy and unlawful assembly. summary offence a less serious criminal offence that carries relatively minor penalties Indictable Offences Indictable offences are more serious offences. There are three classifications of indictable offences. First, some indictable offences are within the exclusive jurisdiction of a superior court. They include the most serious offences, such as first-degree murder. Second, some indictable offences are within the exclusive jurisdiction of the provincial court. They are the least serious indictable offences, such as keeping a gaming or betting house and keeping a common bawdy house. Third, some indictable offences are electable offences, which means the accused decides if the case will be heard in a provincial court or in a superior court. Offences that are electable include manslaughter. Hybrid Offences Hybrid offences may proceed as indictable offences or as summary offences, at the discretion of the Crown. Remember that summary offences have a limitations period of six months. Imagine if the accused could elect to proceed either summarily or by indictment; the accused would always elect to proceed summarily if the crime was committed more than six months ago. An example of a hybrid offence is assault. indictable offence a more serious criminal offence that may carry very serious penalties electable offence a indictable offence that can be heard in provincial court or in superior court, at the discretion of the accused hybrid offence a criminal offence that can proceed as a summary offence or indictable offence, at the discretion of the Crown Defences The accused may choose not to mount a defence if it is believed that the Crown has not proven each element of the offence. Recall that the Crown must prove c02.indd 43 9/13/2013 8:12:12 PM 44 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview Negate actus reus Involuntary act Automatism (insane or not insane) Negate mens rea Insanity Intoxication Mistake of fact Justification Defence of property Self-defence Correction of children Excuse Entrapment Provocation Necessity Duress Figure 2.5 Classes of defences justification the accused admits having committed the offence, but argues that it was justified (e.g., self-defence) excuse the accused admits having committed the offence but argues that there is a legal excuse for the act (e.g., provocation) negating the actus reus a situation in which the accused admits to having committed the offence but argues that the actions were not under voluntary control negating the mens rea a situation in which the accused admits to having committed the offence but argues that the requisite mens rea was absent beyond a reasonable doubt that this accused had the requisite mens rea and actus reus as stated in the Criminal Code. If the accused decides to mount a defence, it may be based on identification—“I did not commit the offence.” If the accused admits to committing the offence, there are four classes of defences (see Figure 2.5). The accused could attempt to negate the actus reus by claiming that it was an involuntary act, such as an assault that took place in the course of an epileptic attack or automatism. The accused could attempt to negate the mens rea by claiming to have been mentally disordered at the time of the offence (more about this in Chapter 3), to have been intoxicated at the time of the offence, or to have reasonably misunderstood critical facts (such as whether the complainant consented to having sex). The accused could use a justification, such as self-defence, defence of property, or correction of children. The accused could claim an excuse for having committed the act, such as entrapment, necessity, duress, provocation, or mistake of law. If the defence involves negating the actus reus or negating the mens rea, the accused need only raise a reasonable doubt with the defence. If the defence involves a justification or excuse, the accused must establish the defence on a balance of probabilities. Evidence When a criminal offence has been committed and there is not a guilty plea, there will be a trial in which evidence will be presented. The evidence will be heard by the trier of law and the trier of fact. Recall the earlier example used to explain the difference between questions of law and questions of fact. The hypothetical issue was that it is a crime to be too tall. The question of law is, “What is too tall?” This is a question for the trier of law to decide. The question of fact is, “How tall is the accused?” This is a question for the trier of fact to decide. If a case is being heard by a judge sitting alone, the judge is the trier of law and the trier of fact. If a trial is before a judge and a jury, the judge is the trier of law and the jury is the trier of fact. In this section, we discuss, very generally, the c02.indd 44 9/13/2013 8:12:12 PM Criminal Offences 45 law of evidence, including the source of evidence law, admissible evidence, and expert evidence. Source of Evidence Law The laws of evidence were developed over the centuries to ensure that courts only hear evidence needed to render fair and just decisions. Although most laws of evidence can be found in case law (i.e., common law), there are statutes that provide for some laws of evidence. The most relevant statutes are the Canada Evidence Act (which governs admissibility of evidence in some criminal trials) and provincial evidence acts. Each province has its own evidence act that governs some criminal proceedings and most civil proceedings. Admissible Evidence As a starting point, all information that is logically probative of a material fact will be admitted in evidence unless it is inherently unreliable (e.g., hearsay evidence), its prejudicial effect outweighs its probative value (e.g., evidence of bad character of the accused), or it should be prohibited on policy grounds (e.g., obtained as a result of a Charter breach). A piece of evidence may be admitted but given no weight— admissibility and weight are separate issues. A three-yearold child may be admitted as a witness, but the trier of fact may decide that the child’s memory is so unreliable that no weight can be given to the testimony. admissibility determination of whether or not evidence can be heard weight determination of how important evidence is deemed to be Opinion/Expert Evidence Ordinarily, witnesses are not allowed to present opinions to court; they are confined to testimony concerning what was perceived through their senses. Expert witnesses testify in court about specialized knowledge they possess and provide opinions based on that specialized knowledge; this is known as expert evidence. Forensic psychologists are often called upon to testify regarding matters of mental health (in the case of a clinical forensic psychologist) or general theory and research in psychology and law. Generally, clinical forensic psychologists are involved as expert witnesses after they have evaluated a defendant; they are called to testify regarding that defendant’s mental state and how it relates to the legal issue at hand (such as insanity, competency, dangerousness, civil commitment, etc.). It is possible, however, for forensic psychologists to serve as general expert witnesses. In this case, instead of testifying regarding specialized knowledge about a particular defendant/complainant, they may be called to testify regarding broader psychological principles in which they have specialized knowledge or expertise. This role is usually performed in conjunction with another role, such as that of researcher, academic, or evaluator, and thus is generally not the only (or even the primary) role in which a forensic psychologist engages. Forensic psychologists in the expert witness role may participate in both criminal and civil c02.indd 45 expert evidence opinion evidence provided by a witness with specialized knowledge 9/13/2013 8:12:12 PM 46 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview proceedings and are usually trained either in general psychology or in a particular psychological specialty such as clinical psychology. In R. v. Mohan (1994), the Supreme Court of Canada provided the following four criteria for admission of expert opinion evidence. The opinion must be necessary. That is, the content of the expert’s testimony is outside the experience and knowledge of the trier of fact, and the trier of fact ought to have this information to help it render a fair and just decision. For instance, until recently, experts could be called to court to explain why a child sexual abuse complainant would not report the offence at the first available opportunity. In fact, most children delay reporting their abuse for a considerable amount of time and for myriad reasons. Without this information about delayed disclosure from an expert, a trier of fact may draw an incorrect and adverse conclusion from a child’s failure to report immediately. The opinion must be relevant to a material issue at trial. For instance, the ability of the accused to form the requisite mens rea for first-degree murder (i.e., planned and deliberate) may be influenced by the amount of alcohol the accused consumed just before the offence. In this case, the effect of a particular amount of alcohol on a particular accused is material. However, if the accused was charged with driving while under the influence of alcohol, intoxication is not a material fact because it is not a defence to the offence. The expert must be properly qualified. That is, the court must find that the expert has the specialized knowledge required to present an opinion. A properly qualified expert is not necessarily a person who has an advanced degree; professional experience is sometimes sufficient to qualify a person as an expert. There are no exclusionary rules that would render the evidence inadmissible. In other words, if the evidence is inadmissible on its face, having it reported by an expert will not make it admissible. For instance, except in particular circumstances, evidence of the “bad character” of the accused is inadmissible. It could not be rendered admissible just because it was tendered by an expert. Even if evidence is admitted, that does not mean it will carry much, or even any, weight. The difference between admissibility and weight is important. As an example, a judge may admit an expert to provide an opinion concerning battered-spouse syndrome, but (perhaps because the Crown was particularly persuasive in its cross-examination of the expert) the trier of fact may choose not to consider the evidence at all or to consider only part of it. Summary As a forensic psychologist, it is essential that you understand the legal system; it will inform your research and will use your expertise to advance legal and policy development as well as to assist with particular disputes. We began by describing, very generally, two models of legal systems: the adversarial and inquisitorial models. Within the Canadian adversarial legal system, the Constitution Act, 1867, sets c02.indd 46 9/13/2013 8:12:12 PM Discussion Questions 47 out which level of government has the authority to pass laws in particular areas. Laws come to us from legislation and from common law. The interpretation and enforcement of the laws are often done by courts and sometimes by administrative tribunals. When a criminal law is broken, a court of law may be called on to determine the guilt of an individual and to administer a sanction. Whether the trial court that makes these determinations is a provincial court or a (provincial) superior court will depend on the type of crime and, in some cases, on decisions made by the Crown and the defence. The Crown has the burden of proving, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the particular accused committed the actus reus and had the requisite mens rea. This is done by presenting admissible evidence in court. Most commonly, this evidence is either physical or is reports of witnesses who have first-hand knowledge of the events. Sometimes the evidence also includes opinions from experts who have met the Mohan criteria. If the Crown appears to have proven every element of the offence, the defence may respond. The accused could deny being the perpetrator or could attempt to negate the mens rea, negate the actus reus, argue a justification, or argue an excuse. All elements of the Canadian legal system must be in accord with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms; if they are not, the discord must be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. Discussion Questions 1. We began this chapter by contrasting the adversarial and inquisitorial legal system. Consider the elements of each system and decide which you prefer. Explain why your choice is a better system. 2. Do you think mental health law should be under federal or provincial jurisdiction? In other words, should mental health law be consistent across Canada or are there unique and regional concerns that can only be addressed through provincial legislations? 3. Most of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms contains protections for persons charged with offences. Is this the group that should be singled out for protection under the Charter? Are there any other groups that you think require special Charter protection? 4. In Canada, we do not have limitation periods for prosecuting indictable criminal offences. If an indictable crime is committed, it can be prosecuted at any time. Most American states have statutes of limitations on criminal offences except for murder. List five advantages and five disadvantages of not having statutes of limitations on criminal offences. 5. If you were a victim of an assault and injured as a result, you could proceed civilly or criminally. List the advantages and disadvantages of each option; try to go beyond what is reported in this chapter. Explain why you would proceed either civilly or criminally. c02.indd 47 9/13/2013 8:12:12 PM 48 Chapter 2 The Canadian Legal System: An Overview Key Terms actus reus, p. 42 inquisitorial legal system, p. 30 admissibility, p. 45 justification, p. 44 adversarial legal system, p. 30 mens rea, p. 42 appellant, p. 37 negating the actus reus, p. 44 electable offence, p. 43 negating the mens rea, p. 44 excuse, p. 44 respondent, p. 37 expert evidence, p. 45 stare decisis, p. 33 hybrid offence, p. 43 summary offence, p. 43 indictable offence, p. 43 weight, p. 45 References Anderson, R. A., & Otto, A. L. (2003). Perceptions of fairness in the justice system: A cross-cultural comparison. Social Behavior and Personality, 31, 557–564. Canada Evidence Act, R. S. C. 1985, c C5. Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11. Constitution Act, 1982. Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982. c 11. Criminal Code, R. S. C. 1985, c. C.46. Cooper, J., & Hall, J. (2000). Reactions of mock jurors to testimony of a court appointed expert. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 18, 719 –729. Merckelbach, H. (2003). Taking recovered memories to court. In P. J. Van Koppen & S. D. Penrod (Eds.), Adversarial versus inquisitorial justice: Psychological perspectives on criminal justice systems (pp. 119 –130). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. R v. Khan, [1990] S.C.J. No 81 (QL). R. v. Mohan, [1994] S.C.J. No 36 (QL). R v. Vaillancourt, [1987] S.C.J. No 83 (QL). Starson v. Swayze, [2003] S.C.J. No 33 (QL). Suggested Readings and Websites The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms: http://laws-lois.justice.gc .ca/eng/Const/page-15.html. Department of Justice Canada: www.justice.gc.ca. Supreme Court of Canada: www.scc-csc.gc.ca. c02.indd 48 9/13/2013 8:12:12 PM