LOCAL GOVERNMENT LAW

PART I – GENERAL PRINCIPLES

A. Corporation

-

1. Definition

o An artificial being created by operation of law, having the right of succession and the

powers, attributes and properties expressly authorized by law or incident to its

existence

-

2. Classification

o Classification of corporations according to purpose:

a. Public – is a corporation that is created by the state, either by general or

special act, for purposes of administration of local government or rendering of

service in the public interest.

b. Private – formed for some private purpose, benefit, aim or end

-

3. Public and Private Corporations, distinguished

o Public – organized for the government of a portion of the state

o Private – formed for some private purpose, benefit, aim or end

-

4. Public Corporation, classified

o Classes of public corporations:

i. Quasi-public corporation – created by the state for a narrow or limited

purpose; a private corporation created pursuant to the Corporation Code that

renders public service or supplies public wants

Examples: Public utility companies, electric companies, water districts,

telecommunication companies

ii. Real public corporation/Municipal corporation – a body politic and

corporate constituted by the incorporation of the inhabitants for the purpose

of local government

-

5. Municipal corporation, defined

o Perception of local governments: A local government is not only a municipal

corporation, meaning we don’t look at it as an entity or a corporation that is clothed

with a personality. It’s also perceived as either political subdivision or a territorial

subdivision.

If we talk about political subdivision, then we look at local governments as

agents of the national governments and therefore, tasked to perform certain

government functions.

If we talk about territorial subdivision, we look at it as a place.

Basis: Sec. 1 Art. 10 Consti - The territorial and political subdivisions of the

Republic of the Philippines are the provinces, cities, municipalities, and

barangays. There shall be autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao and the

Cordilleras as hereinafter provided.

But not only that, we have to deal with local governments as something that

has life, something that performs acts with legal effects.

B. Municipal Corporations

-

1. Elements

o a. Legal creation or incorporation – the law creating or authorizing the creation or

incorporation of a municipal corporation; the law that established the lgu, either by

statute or ordinance in the case of barangays.

o b. Corporate name – the name by which the corporation shall be known

Example: City of Cebu (Basis – the charter)

Sec. 13 – The sangguniang panlalawigan may, in consultation with the

Philippine Historical Institute, change the name of component cities and

municipalities, upon the recommendation of the sanggunian concerned;

provided that the same shall be effective only upon ratification in a plebiscite

conducted for the purpose in the political unit directly affected.

o c. Inhabitants – the people residing in the territory of the corporation

o d. Territory – the land mass where the inhabitants reside, together with the internal

and external waters, and the air space above the land and waters.

-

2. Dual Nature and Functions

o It has dual functions, namely:

a. Public or governmental or political – It acts as an agent of the state for the

government of the territory and the inhabitants; this involves the

administration of powers of the state and the promotion of public welfare; in

this regard, we call a lgu as a political subdivision, that’s why being a political

subdivision, it is an agent of the national government and being an agent of

the national government, the principal is giving the agent the task of

administering its power, that’s why we have local taxation, local police power

and local eminent domain

Examples: Local police power, local taxation, local eminent domain,

public works

b. Private or proprietary – It acts as an agent of the community in the

administration of local affairs. As such, it acts as a separate entity, for its own

purposes, and not as a subdivision of the state. A kind of power that is

exercised for the special benefit and advantage of the community, thus, it’s

not a necessary benefit, it’s something that the lgu can do without.

Examples: Maintenance of parks, cemeteries, establishment of

markets, fiestas and recreation

o Basis: Section 15. Political and Corporate Nature of Local Government Units. - Every

local government unit created or recognized under this Code is a body politic and

corporate endowed with powers to be exercised by it in conformity with law. As such,

it shall exercise powers as a political subdivision of the national government and as a

corporate entity representing the inhabitants of its territory.

So, the framework therefore is accountability:

If the lgu is exercising a governmental function, then it becomes

accountable to the national government, but if the lgu is exercising

corporation functions, then it is not accountable to the national

government but it is accountable to the people.

o Bar Question: Johnny was employed as a driver by the Municipality of Calumpit.

While driving recklessly a municipal dump truck with its load of sand for the repair of

municipal streets, Johnny hit a jeepney and 2 passengers of the jeepney died. Is the

municipality liable for the negligence of Johnny?

YES, under Sec. 24:

Section 24. Liability for Damages. - Local government units and their

officials are not exempt from liability for death or injury to persons or

damage to property.

Whether the act is governmental or proprietary

Alternative answer:

NO. If it is governmental act, then, as a rule, there is no liability except

only when it is performed by a special agent, such that conversely, if it

is proprietary, then the agent of the state cannot enjoy that privilege

because it is proprietary and therefore, not related to the national

government, then it should be held liable.

o BARA LIDASAN VS COMELEC

In a municipality in Mindanao, it was created by a statute. The problem was

when such law was passed, it enumerated barangays or barrios belonging to a

different province.

Could we indulge in the assumption that Congress still intended, by the Act, to

create the restricted area of nine barrios in the towns of Butig and Balabagan

in Lanao del Sur into the town of Dianaton, if the twelve barrios in the towns of

Buldon and Parang, Cotabato were to be excluded therefrom? The answer

must be in the negative.

Municipal corporations perform twin functions. Firstly. They serve as an

instrumentality of the State in carrying out the functions of government.

Secondly. They act as an agency of the community in the administration of

local affairs. It is in the latter character that they are a separate entity acting

for their own purposes and not a subdivision of the State.

Consequently, several factors come to the fore in the consideration of whether

a group of barrios is capable of maintaining itself as an independent

municipality. Amongst these are population, territory, and income.

When the foregoing bill was presented in Congress, unquestionably, the

totality of the twenty-one barrios — not nine barrios — was in the mind of the

proponent thereof. That this is so, is plainly evident by the fact that the bill

itself, thereafter enacted into law, states that the seat of the government is in

Togaig, which is a barrio in the municipality of Buldon in Cotabato. And then

the reduced area poses a number of questions, thus: Could the observations as

to progressive community, large aggregate population, collective income

sufficient to maintain an independent municipality, still apply to a motley

group of only nine barrios out of the twenty-one? Is it fair to assume that the

inhabitants of the said remaining barrios would have agreed that they be

formed into a municipality, what with the consequent duties and liabilities of

an independent municipal corporation? Could they stand on their own feet

with the income to be derived in their community? How about the peace and

order, sanitation, and other corporate obligations? This Court may not supply

the answer to any of these disturbing questions. And yet, to remain deaf to

these problems, or to answer them in the negative and still cling to the rule on

separability, we are afraid, is to impute to Congress an undeclared will. With

the known premise that Dianaton was created upon the basic considerations

of progressive community, large aggregate population and sufficient income,

we may not now say that Congress intended to create Dianaton with only nine

— of the original twenty-one — barrios, with a seat of government still left to

be conjectured. For, this unduly stretches judicial interpretation of

congressional intent beyond credibility point. To do so, indeed, is to pass the

line which circumscribes the judiciary and tread on legislative premises. Paying

due respect to the traditional separation of powers, we may not now melt and

recast Republic Act 4790 to read a Dianaton town of nine instead of the

originally intended twenty-one barrios. Really, if these nine barrios are to

constitute a town at all, it is the function of Congress, not of this Court, to spell

out that congressional will.

Republic Act 4790 is thus indivisible, and it is accordingly null and void in its

totality.

The idea that it must be self-sufficient therefore is relevant to the second

function that it must be a corporate entity representing the inhabitants of the

community.

o SURIGAO ELECTRIC CO. INC. VS MUNICIPALITY OF SURIGAO

When Municipality of surigao wanted to operate an electric company of its

own, it did so without a CPC, pursuant to the Public Service Act which says

that “government instrumentalities or entities are exempt from getting CPC if

they decide to operate public utility companies”. The private electric company

argued that a lgu is not a government instrumentality or entity.

There has been a recognition by this Court of the dual character of a municipal

corporation, one as governmental, being a branch of the general

administration of the state, and the other as quasi-private and

corporate…………… It would, therefore, be to erode the term "government

entities" of its meaning if we are to reverse the Public Service Commission and

to hold that a municipality is to be considered outside its scope.

So, the SC said that as a lgu possessing the first function of being an agent of

the state and that is being a political subdivision, it is a government

instrumentality or entity, therefore, it is exempt from obtaining the CPC as

provided for in the Public Service Act.

-

3. Sources of Powers

o 1987 consti Art. 10

o RA 7160 – LGC of 1991 which took effect on January 1, 1992

o Statutes or acts that are not inconsistent with the Consti and the LGC

o Charter – the law that creates the LGU

o Doctrine of the right of self-government, but applies only in states which adhere to

the doctrine

-

4. Classification of Powers

o i. express, implied, inherent (powers necessary and proper for governance, e.g. to

promote health and safety, enhance prosperity, improve morals of inhabitants)

o ii. public or governmental, private or proprietary

o iii. intramural, extramural

o iv. mandatory, directory; ministerial, discretionary

-

5. Types of Municipal Corporations

o i. De jure – created with all the elements of a municipal corporation being present

o ii. De facto – where there is colorable compliance (not full or complete, but simply

colorable, meaning almost or seems like) with the requisites of a de jure municipal

corporation

Example of colorable compliance: There’s a law creating the municipal

corporation but it is defective

Which municipal corporation acts with legal affects?

BOTH

Philosophy behind accepting de facto municipal corporation:

Where there is authority in law for a municipal corporation, the

organization of the people of a given territory as such a corporation

under the color of delegated authority followed by a user in good faith

of the governmental powers will be recognized by law as municipal

corporation de facto

Where through the failure to comply with constitutional or statutory

requirements, the corporation cannot be considered de jure

What are the bases or reasons for de facto municipal corporation?

Security

Prescription

o Meaning, lgus can exist via prescription.

The basis for this doctrine is the very strong public policy supporting:

o i. Security of lgus; and

o ii. Conduct of their business against attack grounded upon

collateral inquiry into the legality of their organization

What is the operative fact doctrine?

Certain legal effects of the statute prior to its declaration of

unconstitutionality may be recognized.

This is the modern view regarding the effects of declaration of

unconstitutionality of a law, meaning if a law for example that creates a

lgu will be declared as unconstitutional, the court is mindful that during

the interim, that lgu must have already performed acts pursuant to its

being a lgu.

o How do we treat these acts? Should we consider them as void

acts, with no effects?

o The operative fact doctrine means that insofar as local

government law is concerned, before a law creating a lgu is

declared unconstitutional, the acts of the lgu concerned shall be

respected and shall be given legal effects.

o The acts of such entity will be respected and will be recognized

as valid and binding by the state as if it is a de jure municipal

corporation.

o But long use of corporate powers does not silenced the state,

that’s why even if there is long use of corporate powers, the

state is not in estoppel as it can never be in estoppel except in

few special cases, but as a rule, it should not be considered in

estoppel, so it can still question the existence of a lgu in a quo

warranto proceeding.

o A defective incorporation may however be obviated and the de

facto unit can actually become de jure by subsequent legislative

recognition or subsequent validation.

-

6. De Facto Municipal Corporation Doctrine; Elements

o i. valid law authorizing incorporation

o ii. attempt in good faith to organize it

o iii. colorable compliance with law

o iv. assumption of corporate powers

MUNICIPALITY OF JIMENEZ VS BAS, JR.

In this case, the Municipality of Sinacaban was created via EO 258 (this

is an executive act, not a legislative act), and since then, it had been

exercising the powers of a lgu.

PELAEZ VS AUDITOR GENERAL – The SC declared as unconstitutional

Sec. 68 of the RAC which authorized the President to create

municipalities through EO because the creation of municipalities is a

legislative function and not an executive function. With this declaration,

municipalities created by EO could not claim to be de facto municipal

corporations, because there was not valid authorizing incorporation.

However, later on, the case of Pelaez rendered invalid the creation of

certain municipalities pursuant to an executive order, but under the

petition of Pelaez, EO 258 creating Sinacaban was not included, so it

continued to exist as such municipality until its existence was

questioned.

The SC said that Sinacaban attained a status of a de facto municipal

corporation because its existence had not been questioned for more

than 40 years. [long use of corporate powers; this is an example of

prescription]

MUNICIPALITY OF SAN NARCISO VS MENDEZ, SR. – Sec. 442(d) of the LGC to

the effect that municipal districts “organized pursuant to presidential

issuances or executive orders and which have their respective sets of elective

municipal officials holding office at the time of the effectivity of the Code shall

henceforth be considered as regular municipalities” converted municipal

districts organized pursuant to presidential issuances or executive orders into

regular municipalities. Curative laws, which in essence are retrospective, and

aimed at giving “validity to acts done that would have been invalid under

existing laws, as if existing laws have been complied with,” are validly

accepted in this jurisdiction.

This involves the municipality of San Andres also created via executive

act.

Then came the Pelaez ruling.

SC said that San Andres became de jure by subsequent recognition

because it was included in the Ordinance to the 1987 consti

apportioning the seats of the HR (as one of the 12 municipalities

composing the 3rd district of Quezon).

This is an example of subsequent recognition or validation, whether it

was intentional or not.

MUNICIPALITY OF CANDIJAY VS CA

Sec. 442 (d) of LGC: “Municipalities existing as of the date of the

effectivity of this Code shall continue to exist and operate as such.

Existing municipal districts organized pursuant to presidential issuances

or EOs and which have their respective set of elective municipal officials

holding office at the time of the effectivity of this Code shall henceforth

be considered as regular municipalities.” [curative legislation]

SULTAN OSOP CAMID VS OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

Sec. 442 (d) of the LGC does not sanction recognition of just any

municipality;

Only those that can prove continued exercise of corporate powers can

be covered;

Incidentally, the SC, being not a trier of facts, cannot ascertain the

truthfulness of petitioner’s allegation of continued exercise of corporate

powers. (there should have been a trial court that ascertained it)

-

7. Method of challenging existence of municipal corporation

o Quo warranto proceeding (under what authority) – this is a direct challenge. If you

question or challenge a lgu, you need to institute a proceeding for that purpose. You

cannot make it as a defense. It should be a direct attack and the method is quo

warranto to be initiated by the state.

o MALABANG VS BENITO – No collateral attack shall lie; an inquiry into the legal

existence of a municipal corporation is reserved to the state in a proceeding for quo

warranto which is a direct proceeding. But this rule applies only when the municipal

corporation is, at least, a de facto municipal corporation.

Proper party and nature of challenge: If the LGU is at least a de facto

municipal corporation, only the STATE in a DIRECT ACTION.

But if the LGU is not even de facto but a nullity, ANY PERSON in either

DIRECT OR COLLATERAL ATTACK.

o Bar question: Suppose that 1 year after Masigla was constituted as a municipality,

the law creating it is voided because of defects. Would that invalidate the acts of the

municipality and/or its municipal officers?

Answer: NO, Doctrine of Operative Fact

C. Overview of Philippines Local Government System

-

1. The Unitary vs. the Federal Forms of Government

o Ours is a unitary form of government, not federal.

o Generally, powers of government may be distributed either horizontally or vertically:

It is horizontal if the distribution is among the 3 branches of the government

in the national government. It is in this kind of distribution that we distinguish

between presidential (separation of powers) and parliamentary (fusion of

powers of the legislative and executive).

It is vertical if the distribution is between the national government and the

local government. It is in here that we distinguish unitary from federal.

o Distinction of unitary and federal:

A unitary government is a single, centralized government, exercising powers

over both the internal and external affairs of the state, the powers are shared

by the national government and the local government; while a federal

government consists of autonomous state (local) government units merged

into a single state, with the national government exercising a limited degree

of power over the domestic affairs but generally full direction of the external

affairs of the state, the powers are divided by the national government and

the local government.

o In a unitary government, we have national government creating local governments.

Thus in our jurisdiction, our principle is that lgus derive both existence and powers

from the national government.

o Which authority possesses residual powers or who is the repository of residual

powers?

In the horizontal distribution of powers, it is the President – single executive

doctrine. In the RAC, it says that all other powers not vested in the President,

in the Congress or judiciary, shall be deemed a power that can be exercised by

the President. To that extent, we call our form of government presidential.

In the vertical distribution of powers, it is the national government through

congress. Congress exercises plenary legislative power.

o ZOOMZAT INC. VS PEOPLE

Petitioner assails the findings of Special Prosecutor Pascual that under

Executive Order No. 205, it is the National Telecommunications Commission

(NTC), and not the local government unit, that has the power and authority to

allow or disallow the operation of cable television. It argues that while the

NTC has the authority to grant the franchise to operate a cable television, this

power is not exclusive because under the Local Government Code, the city

council also has the power to grant permits, licenses and franchises in aid of

the local government unit’s regulatory or revenue raising powers.

Executive Order No. 205 clearly provides that only the NTC could grant

certificates of authority to cable television operators and issue the necessary

implementing rules and regulations. Likewise, Executive Order No. 436, vests

with the NTC the regulation and supervision of cable television industry in the

Philippines.

It is clear that in the absence of constitutional or legislative authorization,

municipalities have no power to grant franchises. Consequently, the protection

of the constitutional provision as to impairment of the obligation of a contract

does not extend to privileges, franchises and grants given by a municipality in

excess of its powers, or ultra vires.

But, lest we be misunderstood, nothing herein should be interpreted as to strip

LGUs of their general power to prescribe regulations under the general welfare

clause of the Local Government Code. It must be emphasized that when E.O.

No. 436 decrees that the "regulatory power" shall be vested "solely" in the

NTC, it pertains to the "regulatory power" over those matters, which are

peculiarly within the NTC’s competence …

There is no dispute that respondent Sangguniang Panlungsod, like other local

legislative bodies, has been empowered to enact ordinances and approve

resolutions under the general welfare clause of B.P. Blg. 337, the Local

Government Code of 1983. That it continues to possess such power is clear

under the new law, R.A. No. 7160 (the Local Government Code of 1991).

Indeed, under the general welfare clause of the Local Government Code, the

local government unit can regulate the operation of cable television but only

when it encroaches on public properties, such as the use of public streets,

rights of ways, the founding of structures, and the parceling of large regions.

Beyond these parameters, its acts, such as the grant of the franchise to

Spacelink, would be ultra vires.

-

2. Philippines Local Government System and the concepts of Local Autonomy,

Decentralization, Devolution, and Deconcentration

o Definition of terms:

Local autonomy –in the Philippines, it means that public administrative

powers over local affairs are delegated to political subdivisions. It refers to

decentralization of administrative powers or functions.

But in general, LIMBONA VS MANGELIN said that autonomy is either

decentralization of administration or decentralization of power. The

second is abdication by the national government of political power in

favor of the local government (essence in a federal set-up); the first

consists merely in the delegation of administrative powers to broaden

the base of governmental power (essence in a unitary set-up). Against

the first, there can be no valid constitutional challenge.

Local autonomy is the degree of self-determination exercised by lgus

vis-à-vis the central government. The system of achieving local

autonomy is known as decentralization and this system is realized

through the process called devolution.

Decentralization – is a system whereby lgus shall be given more powers,

authority and responsibilities and resources and a direction by which this is

done is from the national government to the local government

Devolution – refers to the act by which the national government confers

power and authority upon the various local government units to perform

specific functions and responsibilities.

This includes the transfer to local government units of the records,

equipment, and other assets and personnel of national agencies and

offices corresponding to the devolved powers, functions, and

responsibilities.

Distinguish devolution from deconcentration:

Deconcentration is different. If devolution involves the transfer of

resources, powers from national government to lgus, deconcentration

is from national office to a local office.

Deconcentration is the transfer of authority and power to the

appropriate regional offices or field offices of national agencies or

offices whose major functions are not devolved to local government

units.

Kung i-devolve sa lgus, that’s devolution. Kung i-devolve sa local offices

or field offices, dili lgu, that’s deconcentration.

o LINA VS PANO - Since Congress has allowed the PCSO to operate lotteries which

PCSO seeks to conduct in Laguna, pursuant to its legislative grant of authority, the

province’s Sangguniang Panlalawigan cannot nullify the exercise of said authority by

preventing something already allowed by Congress.

Ours is still a unitary form of government, not a federal state. Being so, any

form of autonomy granted to local governments will necessarily be limited and

confined within the extent allowed by the central authority. Besides, the

principle of local autonomy under the 1987 Constitution simply means

"decentralization". It does not make local governments sovereign within the

state or an "imperium in imperio".

To conclude our resolution of the first issue, respondent mayor of San Pedro,

cannot avail of Kapasiyahan Bilang 508, Taon 1995, of the Provincial Board of

Laguna as justification to prohibit lotto in his municipality. For said resolution

is nothing but an expression of the local legislative unit concerned. The

Board's enactment, like spring water, could not rise above its source of power,

the national legislature.

In sum, we find no reversible error in the RTC decision enjoining Mayor

Cataquiz from enforcing or implementing the Kapasiyahan Blg. 508, T. 1995, of

the Sangguniang Panlalawigan of Laguna. That resolution expresses merely a

policy statement of the Laguna provincial board. It possesses no binding legal

force nor requires any act of implementation. It provides no sufficient legal

basis for respondent mayor's refusal to issue the permit sought by private

respondent in connection with a legitimate business activity authorized by a

law passed by Congress.

o SAN JUAN VS CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION

All the assigned errors relate to the issue of whether or not the private

respondent is lawfully entitled to discharge the functions of PBO (Provincial

Budget Officer) of Rizal pursuant to the appointment made by public

respondent DBM's Undersecretary upon the recommendation of then

Director Abella of DBM Region IV.

The petitioner-governor’s arguments rest on his contention that he has the

sole right and privilege to recommend the nominees to the position of PBO

and that the appointee should come only from his nominees. In support

thereof, he invokes Section 1 of Executive Order No. 112.

The issue before the Court is not limited to the validity of the appointment of

one Provincial Budget Officer. The tug of war between the Secretary of Budget

and Management and the Governor of the premier province of Rizal over a

seemingly innocuous position involves the application of a most important

constitutional policy and principle, that of local autonomy. We have to obey

the clear mandate on local autonomy. Where a law is capable of two

interpretations, one in favor of centralized power in Malacañang and the other

beneficial to local autonomy, the scales must be weighed in favor of

autonomy.

The exercise by local governments of meaningful power has been a national

goal since the turn of the century. And yet, inspite of constitutional provisions

and, as in this case, legislation mandating greater autonomy for local officials,

national officers cannot seem to let go of centralized powers. They deny or

water down what little grants of autonomy have so far been given to

municipal corporations.

When the Civil Service Commission interpreted the recommending power of

the Provincial Governor as purely directory, it went against the letter and spirit

of the constitutional provisions on local autonomy. If the DBM Secretary

jealously hoards the entirety of budgetary powers and ignores the right of

local governments to develop self-reliance and resoluteness in the handling of

their own funds, the goal of meaningful local autonomy is frustrated and set

back.

The PBO is expected to synchronize his work with DBM. More important,

however, is the proper administration of fiscal affairs at the local level.

Provincial and municipal budgets are prepared at the local level and after

completion are forwarded to the national officials for review. They are

prepared by the local officials who must work within the constraints of those

budgets. They are not formulated in the inner sanctums of an all-knowing

DBM and unilaterally imposed on local governments whether or not they are

relevant to local needs and resources. It is for this reason that there should be

a genuine interplay, a balancing of viewpoints, and a harmonization of

proposals from both the local and national officials. It is for this reason that

the nomination and appointment process involves a sharing of power

between the two levels of government.

Our national officials should not only comply with the constitutional

provisions on local autonomy but should also appreciate the spirit of liberty

upon which these provisions are based.

o Sec. 25 Art. 2 1987 consti– The State shall ensure the autonomy of local governments.

o Sec. 2 Art. 10 1987 consti – The territorial and political subdivisions shall enjoy local

autonomy.

o Secs. 2-3

Section 2. Declaration of Policy.

(a) It is hereby declared the policy of the State that the territorial and

political subdivisions of the State shall enjoy genuine and meaningful

local autonomy to enable them to attain their fullest development as

self-reliant communities and make them more effective partners in the

attainment of national goals. Toward this end, the State shall provide

for a more responsive and accountable local government structure

instituted through a system of decentralization whereby local

government units shall be given more powers, authority,

responsibilities, and resources. The process of decentralization shall

proceed from the national government to the local government units.

(b) It is also the policy of the State to ensure the accountability of local

government units through the institution of effective mechanisms of

recall, initiative and referendum.

(c) It is likewise the policy of the State to require all national agencies

and offices to conduct periodic consultations with appropriate local

government units, nongovernmental and people's organizations, and

other concerned sectors of the community before any project or

program is implemented in their respective jurisdictions.

Section 3. Operative Principles of Decentralization. - The formulation and

implementation of policies and measures on local autonomy shall be guided by

the following operative principles:

(a) There shall be an effective allocation among the different local

government units of their respective powers, functions, responsibilities,

and resources;

(b) There shall be established in every local government unit an

accountable, efficient, and dynamic organizational structure and

operating mechanism that will meet the priority needs and service

requirements of its communities;

(c) Subject to civil service law, rules and regulations, local officials and

employees paid wholly or mainly from local funds shall be appointed or

removed, according to merit and fitness, by the appropriate appointing

authority;

(d) The vesting of duty, responsibility, and accountability in local

government units shall be accompanied with provision for reasonably

adequate resources to discharge their powers and effectively carry out

their functions: hence, they shall have the power to create and broaden

their own sources of revenue and the right to a just share in national

taxes and an equitable share in the proceeds of the utilization and

development of the national wealth within their respective areas;

(e) Provinces with respect to component cities and municipalities, and

cities and municipalities with respect to component barangays, shall

ensure that the acts of their component units are within the scope of

their prescribed powers and functions;

(f) Local government units may group themselves, consolidate or

coordinate their efforts, services, and resources commonly beneficial to

them;

(g) The capabilities of local government units, especially the

municipalities and barangays, shall be enhanced by providing them

with opportunities to participate actively in the implementation of

national programs and projects;

(h) There shall be a continuing mechanism to enhance local autonomy

not only by legislative enabling acts but also by administrative and

organizational reforms;

(i) Local government units shall share with the national government the

responsibility in the management and maintenance of ecological

balance within their territorial jurisdiction, subject to the provisions of

this Code and national policies;

(j) Effective mechanisms for ensuring the accountability of local

government units to their respective constituents shall be strengthened

in order to upgrade continually the quality of local leadership;

(k) The realization of local autonomy shall be facilitated through

improved coordination of national government policies and programs

an extension of adequate technical and material assistance to less

developed and deserving local government units;

(l) The participation of the private sector in local governance,

particularly in the delivery of basic services, shall be encouraged to

ensure the viability of local autonomy as an alternative strategy for

sustainable development; and

(m) The national government shall ensure that decentralization

contributes to the continuing improvement of the performance of local

government units and the quality of community life.

o Section 17. Basic Services and Facilities. - (a) Local government units shall endeavor

to be self-reliant and shall continue exercising the powers and discharging the duties

and functions currently vested upon them. They shall also discharge the functions and

responsibilities of national agencies and offices devolved to them pursuant to this

Code. Local government units shall likewise exercise such other powers and discharge

such other functions and responsibilities as are necessary, appropriate, or incidental

to efficient and effective provisions of the basic services and facilities enumerated

herein.

o (e) National agencies or offices concerned shall devolve to local government units the

responsibility for the provision of basic services and facilities enumerated in this

Section within six (6) months after the effectivity of this Code.

o As used in this Code, the term "devolution" refers to the act by which the national

government confers power and authority upon the various local government units

to perform specific functions and responsibilities.

o (i) The devolution contemplated in this Code shall include the transfer to local

government units of the records, equipment, and other assets and personnel of

national agencies and offices corresponding to the devolved powers, functions, and

responsibilities.

o Section 528. Deconcentration of Requisite Authority and Power. - The national

government shall, six (6) months after the effectivity of this Code, effect the

deconcentration of requisite authority and power to the appropriate regional

offices or field offices of national agencies or offices whose major functions are not

devolved to local government units.

D. Local Governments in the Philippines

-

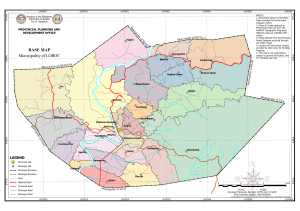

1. Territorial and Political Subdivisions: Provinces, Cities, Municipalities, Barangays

o Kinds of lgus:

i. Regular lgus – are provinces, cities, municipalities and barangays.

Note: Sitio is not a recognized lgu.

ii. Autonomous regions – ARMM and the Cordilleras

iii. Special lgus – special metropolitan political subdivisions

o Kinds of cities:

i. Component cities

Inhabitants can vote for provincial candidates and can run for

provincial elective posts.

Under the supervisory power of the province

ii. Independent component city (ICC)

Independent in the sense that the charter prohibits the voters from

voting for provincial elective posts and this is outside the supervisory

power of the province

Inhabitants cannot vote for provincial elective posts neither can they

run for provincial elective posts not because of income factor but

simply because the charter prohibits the voters from voting or running

for provincial posts.

iii. Highly-urbanized city

Independent from the province by reason of status

It’s outside the supervisory power of the province

o Reason: Status

The voters cannot vote and run for provincial elective officials and

offices.

o But what about Mandaue City – why can they still vote for

provincial elective officials? So the question is can there be a

highly-urbanized city whose voters can still vote for provincial

officials?

YES.

Basis: Section 452. Highly Urbanized Cities. Qualified

voters of cities who acquired the right to vote for

elective provincial officials prior to the classification of

said cities as highly-urbanized after the ratification of

the Constitution and before the effectivity of this Code,

shall continue to exercise such right.

Vested-right theory

o Sec. 1 Art. X consti–The territorial and political subdivisions of the Republic of the

Philippines are the provinces, cities, municipalities, and barangays. There shall be

autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao and the Cordilleras as hereinafter provided.

o Sec. 12 Art. X consti – Cities that are highly urbanized, as determined by law, and

component cities whose charters prohibit their voters from voting for provincial

elective officials, shall be independent of the province. The voters of component cities

within a province, whose charters contain no such prohibition, shall not be deprived

of their right to vote for elective provincial officials.

ABELLA VS COMELEC

The main issue in these consolidated petitions centers on who is the

rightful governor of the province of Leyte 1) petitioner Adelina

Larrazabal (G.R. No. 100739) who obtained the highest number of

votes in the local elections of February 1, 1988 and was proclaimed as

the duly elected governor but who was later declared by the

Commission on Elections (COMELEC) "... to lack both residence and

registration qualifications for the position of Governor of Leyte as

provided by Art. X, Section 12, Philippine Constitution in relation to

Title II, Chapter I, Sec. 42, B.P. Blg. 137 and Sec. 89, R.A. No. 179 and is

hereby disqualified as such Governor"

Failing in her contention that she is a resident and registered voter of

Kananga, Leyte, the petitioner poses an alternative position that her

being a registered voter in Ormoc City was no impediment to her

candidacy for the position of governor of the province of Leyte.

Section 12, Article X of the Constitution provides:

o Cities that are highly urbanized, as determined by law, and

component cities whose charters prohibit their voters from

voting for provincial elective officials, shall be independent of

the province. The voters of component cities within a province,

whose charters contain no such prohibition, shall not be

deprived of their right to vote for elective provincial officials.

Section 89 of Republic Act No. 179 creating the City of Ormoc provides:

o Election of provincial governor and members of the Provincial

Board of the members of the Provincial Board of the Province of

Leyte — The qualified voters of Ormoc City shall not be qualified

and entitled to vote in the election of the provincial governor

and the members of the provincial board of the Province of

Leyte.

Relating therefore, section 89 of R.A. 179 to section 12, Article X of the

Constitution one comes up with the following conclusion: that Ormoc

City when organized was not yet a highly-urbanized city but is,

nevertheless, considered independent of the province of Leyte to

which it is geographically attached because its charter prohibits its

voters from voting for the provincial elective officials. The question

now is whether or not the prohibition against the 'city's registered

voters' electing the provincial officials necessarily mean, a prohibition

of the registered voters to be elected as provincial officials.

The petitioner citing section 4, Article X of the Constitution, to wit:

o Sec. 4. The President of the Philippines shall exercise general

supervision over local governments. Provinces with respect to

component cities and municipalities and cities and municipalities

with respect to component barangays, shall ensure that the acts

of their component units are within the scope of their

prescribed powers and functions.

submits that "while a Component City whose charter prohibits its

voters from participating in the elections for provincial office, is indeed

independent of the province, such independence cannot be equated

with a highly urbanized city; rather it is limited to the administrative

supervision aspect, and nowhere should it lead to the conclusion that

said voters are likewise prohibited from running for the provincial

offices." (Petition, p. 29)

The argument is untenable.

Section 12, Article X of the Constitution is explicit in that aside from

highly-urbanized cities, component cities whose charters prohibit their

voters from voting for provincial elective officials are independent of

the province. In the same provision, it provides for other component

cities within a province whose charters do not provide a similar

prohibition. Necessarily, component cities like Ormoc City whose

charters prohibit their voters from voting for provincial elective officials

are treated like highly urbanized cities which are outside the supervisory

power of the province to which they are geographically attached. This

independence from the province carries with it the prohibition or

mandate directed to their registered voters not to vote and be voted for

the provincial elective offices. The resolution in G.R. No. 80716 entitled

Peralta v. The Commission on Elections, et al. dated December 10, 1987

applies to this case. While the cited case involves Olongapo City which is

classified as a highly urbanized city, the same principle is applicable.

Moreover, Section 89 of Republic Act 179, independent of the

constitutional provision, prohibits registered voters of Ormoc City from

voting and being voted for elective offices in the province of Leyte. We

agree with the COMELEC en banc that "the phrase 'shall not be

qualified and entitled to vote in the election of the provincial governor

and the members of the provincial board of the Province of Leyte'

connotes two prohibitions — one, from running for and the second,

from voting for any provincial elective official."

-

2. Autonomous Regions

o Sec. 1 Art. X consti – The territorial and political subdivisions of the Republic of the

Philippines are the provinces, cities, municipalities, and barangays. There shall be

autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao and the Cordilleras as hereinafter provided.

-

3. Special Metropolitan Political Subdivisions

o Sec. 11 Art. 10 consti – The Congress may, by law, create special metropolitan

political subdivisions, subject to a plebiscite as set forth in Section 10 hereof. The

component cities and municipalities shall retain their basic autonomy and shall be

entitled to their own local executive and legislative assemblies. The jurisdiction of the

metropolitan authority that will thereby be created shall be limited to basic services

requiring coordination.

o MMDA VS BEL-AIR VILLAGE – The MMDA which has no police and legislative powers,

has no power to enact ordinances for the general welfare of the inhabitants of Metro

Manila. It has no authority to order the opening of Neptune Street, a private

subdivision road in Makati City and cause the demolition of it’s perimeter walls.

MMDA is not even a special metropolitan political subdivision because there

was no plebiscite when the law created it and the President exercises not just

supervision but control over it.

MMDA has purely administrative function.

Because MMDA is not a political subdivision, it cannot exercise political

power like police power.

E. Loose Federation of LGUs and Regional Development Councils

-

Sec. 13 Art. 10 Consti – Local government units may group themselves, consolidate or

coordinate their efforts, services, and resources for purposes commonly beneficial to them in

accordance with law.

-

Section 33. Cooperative Undertakings Among Local Government Units. - Local government

units may, through appropriate ordinances, group themselves, consolidate, or coordinate

their efforts, services, and resources for purposes commonly beneficial to them. In support of

such undertakings, the local government units involved may, upon approval by the

sanggunian concerned after a public hearing conducted for the purpose, contribute funds,

real estate, equipment, and other kinds of property and appoint or assign personnel under

such terms and conditions as may be agreed upon by the participating local units through

Memoranda of Agreement.

o Take note: The resultant consolidation would not be a new corporate body. Why?

Because the requirement that an lgu should be created by law is of constitutional

origin. That requirement remains, so that it cannot be done either by MOA or

ordinance. It has to be by law. It cannot be given a separate personality.

-

Sec. 14 Art. 10 consti – The President shall provide for regional development councils or

other similar bodies composed of local government officials, regional heads of departments

and other government offices, and representatives from non-governmental organizations

within the regions for purposes of administrative decentralization to strengthen the

autonomy of the units therein and to accelerate the economic and social growth and

development of the units in the region.

PART II – THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT CODE OF 1991

-

1. Constitutional Mandate

o Sec. 3 Art. 10 consti – The Congress shall enact a local government code which shall

provide for a more responsive and accountable local government structure instituted

through a system of decentralization with effective mechanisms of recall, initiative,

and referendum, allocate among the different local government units their powers,

responsibilities, and resources, and provide for the qualifications, election,

appointment and removal, term, salaries, powers and functions and duties of local

officials, and all other matters relating to the organization and operation of the local

units.

-

2. Sources of the LGC of 1991 (Codified laws)

-

3. Scope of Application

o Section 4. Scope of Application. - This Code shall apply to all provinces, cities,

municipalities, barangays, and other political subdivisions as may be created by law,

and, to the extent herein provided, to officials, offices, or agencies of the national

government.

o Section 526. Application of this Code to Local Government Units in the Autonomous

Regions. - This Code shall apply to all provinces, cities, municipalities and barangays

in the autonomous regions until such time as the regional government concerned

shall have enacted its own local government code.

o Section 529. Tax Ordinances or Revenue Measures. - All existing tax ordinances or

revenue measures of local government units shall continue to be in force and effect

after the effectivity of this Code unless amended by the sanggunian concerned, or

inconsistent with, or in violation of, the provisions of this Code.

o Section 534. Repealing Clause. –

(f) All general and special laws, acts, city charters, decrees, executive orders,

proclamations and administrative regulations, or part or parts thereof which

are inconsistent with any of the provisions of this Code are hereby repealed or

modified accordingly.

LAGUNA LAKE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY VS CA – The provisions of the LGC

do not necessarily repeal the laws creating the LLDA and granting the latter

water rights authority over Laguna de Bay and the lake region.

In this petition for certiorari, prohibition and injunction, the Authority

contends: The Honorable CA committed serious error when it ruled

that the power to issue fishpen permits in Laguna de Bay has been

devolved to concerned (lakeshore) lgus.

Which agency of the Government — the Laguna Lake Development

Authority or the towns and municipalities comprising the region —

should exercise jurisdiction over the Laguna Lake and its environs

insofar as the issuance of permits for fishery privileges is concerned?

We hold that the provisions of Republic Act No. 7160 do not necessarily

repeal the aforementioned laws creating the Laguna Lake Development

Authority and granting the latter water rights authority over Laguna de

Bay and the lake region.

The Local Government Code of 1991 does not contain any express

provision which categorically expressly repeal the charter of the

Authority. It has to be conceded that there was no intent on the part of

the legislature to repeal Republic Act No. 4850 and its amendments.

The repeal of laws should be made clear and expressed.

Considering the reasons behind the establishment of the Authority,

which are environmental protection, navigational safety, and

sustainable development, there is every indication that the legislative

intent is for the Authority to proceed with its mission.

It has to be conceded that the charter of the Laguna Lake Development

Authority constitutes a special law. Republic Act No. 7160, the Local

Government Code of 1991, is a general law. It is basic in statutory

construction that the enactment of a later legislation which is a general

law cannot be construed to have repealed a special law. It is a wellsettled rule in this jurisdiction that "a special statute, provided for a

particular case or class of cases, is not repealed by a subsequent

statute, general in its terms, provisions and application, unless the

intent to repeal or alter is manifest, although the terms of the general

law are broad enough to include the cases embraced in the special

law."

Where there is a conflict between a general law and a special statute,

the special statute should prevail since it evinces the legislative intent

more clearly than the general statute. The special law is to be taken as

an exception to the general law in the absence of special circumstances

forcing a contrary conclusion. This is because implied repeals are not

favored and as much as possible, effect must be given to all enactments

of the legislature. A special law cannot be repealed, amended or altered

by a subsequent general law by mere implication.

Thus, it has to be concluded that the charter of the Authority should

prevail over the Local Government Code of 1991.

The power of the local government units to issue fishing privileges was

clearly granted for revenue purposes.

On the other hand, the power of the Authority to grant permits for

fishpens, fishcages and other aqua-culture structures is for the purpose

of effectively regulating and monitoring activities in the Laguna de Bay

region (Section 2, Executive Order No. 927) and for lake quality control

and management. It does partake of the nature of police power which

is the most pervasive, the least limitable and the most demanding of all

State powers including the power of taxation. Accordingly, the charter

of the Authority which embodies a valid exercise of police power should

prevail over the Local Government Code of 1991 on matters affecting

Laguna de Bay.

Removal from the Authority of the aforesaid licensing authority will

render nugatory its avowed purpose of protecting and developing the

Laguna Lake Region. Otherwise stated, the abrogation of this power

would render useless its reason for being and will in effect denigrate, if

not abolish, the Laguna Lake Development Authority. This, the Local

Government Code of 1991 had never intended to do.

-

4. Rules of Interpretation

o Section 5. Rules of Interpretation. - In the interpretation of the provisions of this Code,

the following rules shall apply:

(a) Any provision on a power of a local government unit shall be liberally

interpreted in its favor, and in case of doubt, any question thereon shall be

resolved in favor of devolution of powers and of the lower local government

unit. Any fair and reasonable doubt as to the existence of the power shall be

interpreted in favor of the local government unit concerned;

(b) In case of doubt, any tax ordinance or revenue measure shall be construed

strictly against the local government unit enacting it, and liberally in favor of

the taxpayer. Any tax exemption, incentive or relief granted by any local

government unit pursuant to the provisions of this Code shall be construed

strictly against the person claiming it.

(c) The general welfare provisions in this Code shall be liberally interpreted to

give more powers to local government units in accelerating economic

development and upgrading the quality of life for the people in the

community;

(d) Rights and obligations existing on the date of effectivity of this Code and

arising out of contracts or any other source of presentation involving a local

government unit shall be governed by the original terms and conditions of said

contracts or the law in force at the time such rights were vested; and

(e) In the resolution of controversies arising under this Code where no legal

provision or jurisprudence applies, resort may be had to the customs and

traditions in the place where the controversies take place.

Objective: To grant genuine local autonomy

-

5. Effectivity

o Section 536. Effectivity Clause. - This Code shall take effect on January first, nineteen

hundred ninety-two, unless otherwise provided herein, after its complete publication

in at least one (1) newspaper of general circulation.

PART III – CREATION, CONVERSION, DIVISION, MERGER, SUBSTANTIAL CHANGE OF BOUNDARY

OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS, AND ABOLITION

A. Regular Political Subdivisions (Provinces, Cities, Municipalities, and Barangays)

-

1. Creation and Conversion

o a. General Requirements: Law, Plebiscite, Compliance with Criteria on income, land

& population

Secs. 10-11 Art. 10 consti

Section 10. No province, city, municipality, or barangay may be created,

divided, merged, abolished, or its boundary substantially altered, except

in accordance with the criteria established in the local government code

and subject to approval by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite in

the political units directly affected.

Section 11. The Congress may, by law, create special metropolitan

political subdivisions, subject to a plebiscite as set forth in Section 10

hereof. The component cities and municipalities shall retain their basic

autonomy and shall be entitled to their own local executive and

legislative assemblies. The jurisdiction of the metropolitan authority

that will thereby be created shall be limited to basic services requiring

coordination.

Section 6. Authority to Create Local Government Units. - A local government

unit may be created, divided, merged, abolished, or its boundaries

substantially altered either by law enacted by Congress in the case of a

province, city, municipality, or any other political subdivision, or by ordinance

passed by the sangguniang panlalawigan or sangguniang panlungsod

concerned in the case of a barangay located within its territorial jurisdiction,

subject to such limitations and requirements prescribed in this Code.

Section 7. Creation and Conversion. - As a general rule, the creation of a local

government unit or its conversion from one level to another level shall be

based on verifiable indicators of viability and projected capacity to provide

services, to wit:

(a) Income. - It must be sufficient, based on acceptable standards, to

provide for all essential government facilities and services and special

functions commensurate with the size of its population, as expected of

the local government unit concerned;

(b) Population. - It shall be determined as the total number of

inhabitants within the territorial jurisdiction of the local government

unit concerned; and

(c) Land Area. - It must be contiguous, unless it comprises two or more

islands or is separated by a local government unit independent of the

others; properly identified by metes and bounds with technical

descriptions; and sufficient to provide for such basic services and

facilities to meet the requirements of its populace.

Compliance with the foregoing indicators shall be attested to by the

Department of Finance (DOF), the National Statistics Office (NSO), and

the Lands Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of

Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

Section 10. Plebiscite Requirement. - No creation, division, merger, abolition,

or substantial alteration of boundaries of local government units shall take

effect unless approved by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite called for

the purpose in the political unit or units directly affected. Said plebiscite shall

be conducted by the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) within one hundred

twenty (120) days from the date of effectivity of the law or ordinance effecting

such action, unless said law or ordinance fixes another date.

Is it mandated that all these general requirements should be complied with?

For example, the requirement on income, land and population, should we

comply with such requirements?

It depends on the lgu concerned. It’s not required all the time that

there should be compliance with income, population and land area,

because it may happen that only 2 of the 3 factors should be complied

with.

TAN VS COMELEC

A plebiscite for creating a new province should include the participation

of the residents of the mother province in order to conform to the

constitutional requirement. XXXXXX BP 885, creating the Province of

Negros del Norte, is declared unconstitutional because it excluded the

voters of the mother province from participating in the plebiscite (and it

did not comply with the area of criterion prescribed in the LGC). XXXX

Where the law authorizing the holding of a plebiscite is

unconstitutional, the Court cannot authorize the holding of a new one.

XXXX The fact that the plebiscite which the petition sought to stop had

already been held and officials of the new province appointed does not

make the petition moot and academic, as the petition raises an issue of

constitutional dimension.

PADILLA VS COMELEC

Even under the 1987 consti, the plebiscite shall include all the voters of

the mother province or the mother municipality.

When the law states that the plebiscite shall be conducted "in the

political units directly affected," it means that residents of the political

entity who would be economically dislocated by the separation of a

portion thereof have a right to vote in said plebiscite. Evidently, what is

contemplated by the phase "political units directly affected," is the

plurality of political units which would participate in the plebiscite.

LOPEZ VS COMELEC

The creation of Metropolitan Manila is valid. The referendum of Feb.

27, 1975 authorized the President to restructure local governments in

the 4 cities and 13 municipalities. XXXXX The President had authority to

issue decrees in 1975. XXXX The 1984 amendment to the 1973 consti

impliedly recognized the existence of Metro Manila by providing

representation of Metro Manila in the Batasan Pambansa.

SULTAN OSOP CAMID VS OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

From this survey of relevant jurisprudence, we can gather the

applicable rules. Pelaez and its offspring cases ruled that the President

has no power to create municipalities, yet limited its nullificatory effects

to the particular municipalities challenged in actual cases before this

Court. However, with the promulgation of the Local Government Code

in 1991, the legal cloud was lifted over the municipalities similarly

created by executive order but not judicially annulled. The de facto

status of such municipalities as San Andres, Alicia and Sinacaban was

recognized by this Court, and Section 442(b) of the Local Government

Code deemed curative whatever legal defects to title these

municipalities had labored under.

Is Andong similarly entitled to recognition as a de facto municipal

corporation? It is not. There are eminent differences between Andong

and municipalities such as San Andres, Alicia and Sinacaban. Most

prominent is the fact that the executive order creating Andong was

expressly annulled by order of this Court in 1965. If we were to affirm

Andong’s de facto status by reason of its alleged continued existence

despite its nullification, we would in effect be condoning defiance of a

valid order of this Court.Court decisions cannot obviously lose their

efficacy due to the sheer defiance by the parties aggrieved.

It bears noting that based on Camid’s own admissions, Andong does not

meet the requisites set forth by Section 442(d) of the Local Government

Code. Section 442(d) requires that in order that the municipality created

by executive order may receive recognition, they must "have their

respective set of elective municipal officials holding office at the time of

the effectivity of [the Local Government] Code." Camid admits that

Andong has never elected its municipal officers at all. This incapacity

ties in with the fact that Andong was judicially annulled in 1965. Out of

obeisance to our ruling in Pelaez, the national government ceased to

recognize the existence of Andong, depriving it of its share of the public

funds, and refusing to conduct municipal elections for the void

municipality.

The failure to appropriate funds for Andong and the absence of

elections in the municipality in the last four decades are eloquent

indicia of the non-recognition by the State of the existence of the town.

The certifications relied upon by Camid, issued by the DENR-CENRO and

the National Statistics Office, can hardly serve the purpose of attesting

to Andong’s legal efficacy. In fact, both these certifications qualify that

they were issued upon the request of Camid, "to support the restoration

or re-operation of the Municipality of Andong, Lanao del Sur," thus

obviously conceding that the municipality is at present inoperative.

We may likewise pay attention to the Ordinance appended to the 1987

Constitution, which had also been relied upon in Jimenez and San

Narciso. This Ordinance, which apportioned the seats of the House of

Representatives to the different legislative districts in the Philippines,

enumerates the various municipalities that are encompassed by the

various legislative districts. Andong is not listed therein as among the

municipalities of Lanao del Sur, or of any other province for that matter.

On the other hand, the municipalities of San Andres, Alicia and

Sinacaban are mentioned in the Ordinance as part of Quezon, Bohol,

and Misamis Occidental respectively.

How about the eighteen (18) municipalities similarly nullified in Pelaez

but certified as existing in the DILG Certification presented by Camid?

The petition fails to mention that subsequent to the ruling in Pelaez,

legislation was enacted to reconstitute these municipalities. It is thus

not surprising that the DILG certified the existence of these eighteen

(18) municipalities, or that these towns are among the municipalities

enumerated in the Ordinance appended to the Constitution. Andong

has not been similarly reestablished through statute. Clearly then, the

fact that there are valid organic statutes passed by legislation

recreating these eighteen (18) municipalities is sufficient legal basis to

accord a different legal treatment to Andong as against these eighteen

(18) other municipalities.

We thus assert the proper purview to Section 442(d) of the Local

Government Code—that it does not serve to affirm or reconstitute the

judicially dissolved municipalities such as Andong, which had been

previously created by presidential issuances or executive orders. The

provision affirms the legal personalities only of those municipalities

such as San Narciso, Alicia, and Sinacaban, which may have been

created using the same infirm legal basis, yet were fortunate enough

not to have been judicially annulled. On the other hand, the

municipalities judicially dissolved in cases such as Pelaez, San Joaquin,

and Malabang, remain inexistent, unless recreated through specific

legislative enactments, as done with the eighteen (18) municipalities

certified by the DILG. Those municipalities derive their legal personality

not from the presidential issuances or executive orders which originally

created them or from Section 442(d), but from the respective legislative

statutes which were enacted to revive them.

And what now of Andong and its residents? Certainly, neither Pelaez or

this decision has obliterated Andong into a hole on the ground. The

legal effect of the nullification of Andong in Pelaez was to revert the

constituent barrios of the voided town back into their original

municipalities, namely the municipalities of Lumbatan, Butig and

Tubaran. These three municipalities subsist to this day as part of Lanao

del Sur, and presumably continue to exercise corporate powers over the

barrios which once belonged to Andong.

If there is truly a strong impulse calling for the reconstitution of

Andong, the solution is through the legislature and not judicial

confirmation of void title. If indeed the residents of Andong have, all

these years, been governed not by their proper municipal governments

but by a ragtag "Interim Government," then an expedient political and

legislative solution is perhaps necessary. Yet we can hardly sanction the

retention of Andong’s legal personality solely on the basis of collective

amnesia that may have allowed Andong to somehow pretend itself into

existence despite its judicial dissolution. Maybe those who insist

Andong still exists prefer to remain unperturbed in their blissful

ignorance, like the inhabitants of the cave in Plato’s famed allegory. But

the time has come for the light to seep in, and for the petitioner and

like-minded persons to awaken to legal reality.

LEAGUE OF CITIES OF THE PHILS. VS COMELEC

The 16 Cityhood Bills do not violate Article X, Section 10 of the

Constitution.

Article X, Section 10 provides—

o Section 10. No province, city, municipality, or barangay may be

created, divided, merged, abolished, or its boundary

substantially altered, except in accordance with the criteria

established in the local government code and subject to approval

by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite in the political units

directly affected.

The tenor of the ponencias of the November 18, 2008 Decision and the

August 24, 2010 Resolution is that the exemption clauses in the 16

Cityhood Laws are unconstitutional because they are not written in the

Local Government Code of 1991 (LGC), particularly Section 450 thereof,

as amended by Republic Act (R.A.) No. 9009, which took effect on June

30, 2001, viz.—

o Section 450. Requisites for Creation. –a) A municipality or a

cluster of barangays may be converted into a component city if it

has a locally generated annual income, as certified by the

Department of Finance, of at least One Hundred Million Pesos

(P100,000,000.00) for at least two (2) consecutive years based

on 2000 constant prices, and if it has either of the following

requisites:

o xxxx

o (c) The average annual income shall include the income accruing

to the general fund, exclusive of special funds, transfers, and

non-recurring income. (Emphasis supplied)

Prior to the amendment, Section 450 of the LGC required only an

average annual income, as certified by the Department of Finance, of at

least P20,000,000.00 for the last two (2) consecutive years, based on

1991 constant prices.

Before Senate Bill No. 2157, now R.A. No. 9009, was introduced by

Senator Aquilino Pimentel, there were 57 bills filed for conversion of 57

municipalities into component cities. During the 11 th Congress (June

1998-June 2001), 33 of these bills were enacted into law, while 24

remained as pending bills. Among these 24 were the 16 municipalities

that were converted into component cities through the Cityhood Laws.

While R.A. No. 9009 was being deliberated upon, Congress was well

aware of the pendency of conversion bills of several municipalities,

including those covered by the Cityhood Laws, desiring to become

component cities which qualified under the P20 million income

requirement of the old Section 450 of the LGC. The interpellation of

Senate President Franklin Drilon of Senator Pimentel is revealing,

Clearly, based on the above exchange, Congress intended that those

with pending cityhood bills during the 11th Congress would not be

covered by the new and higher income requirement of P100 million

imposed by R.A. No. 9009. When the LGC was amended by R.A. No.

9009, the amendment carried with it both the letter and the intent of

the law, and such were incorporated in the LGC by which the

compliance of the Cityhood Laws was gauged.

Notwithstanding that both the 11th and 12th Congress failed to act upon

the pending cityhood bills, both the letter and intent of Section 450 of

the LGC, as amended by R.A. No. 9009, were carried on until the 13 th

Congress, when the Cityhood Laws were enacted. The exemption

clauses found in the individual Cityhood Laws are the express

articulation of that intent to exempt respondent municipalities from the

coverage of R.A. No. 9009.

Even if we were to ignore the above quoted exchange between then

Senate President Drilon and Senator Pimentel, it cannot be denied that

Congress saw the wisdom of exempting respondent municipalities from

complying with the higher income requirement imposed by the

amendatory R.A. No. 9009. Indeed, these municipalities have proven

themselves viable and capable to become component cities of their

respective provinces. It is also acknowledged that they were centers of

trade and commerce, points of convergence of transportation, rich

havens of agricultural, mineral, and other natural resources, and

flourishing tourism spots. In this regard, it is worthy to mention the

distinctive traits of each respondent municipality,

The enactment of the Cityhood Laws is an exercise by Congress of its

legislative power. Legislative power is the authority, under the

Constitution, to make laws, and to alter and repeal them. The

Constitution, as the expression of the will of the people in their original,

sovereign, and unlimited capacity, has vested this power in the

Congress of the Philippines. The grant of legislative power to Congress

is broad, general, and comprehensive. The legislative body possesses

plenary powers for all purposes of civil government. Any power,

deemed to be legislative by usage and tradition, is necessarily

possessed by Congress, unless the Constitution has lodged it elsewhere.

In fine, except as limited by the Constitution, either expressly or

impliedly, legislative power embraces all subjects, and extends to

matters of general concern or common interest.

Without doubt, the LGC is a creation of Congress through its lawmaking powers. Congress has the power to alter or modify it as it did

when it enacted R.A. No. 9009. Such power of amendment of laws was

again exercised when Congress enacted the Cityhood Laws. When

Congress enacted the LGC in 1991, it provided for quantifiable

indicators of economic viability for the creation of local government

units—income, population, and land area. Congress deemed it fit to

modify the income requirement with respect to the conversion of

municipalities into component cities when it enacted R.A. No. 9009,

imposing an amount of P100 million, computed only from locallygenerated sources. However, Congress deemed it wiser to exempt

respondent municipalities from such a belatedly imposed modified

income requirement in order to uphold its higher calling of putting flesh