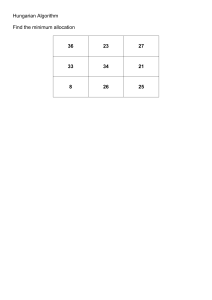

István Petrovics Medieval Pécs and the Monetary Reforms of Charles I The city The city of Pécs is located in the southwestern part of modern Hungary, close to the Croatian border. In 2010 Pécs will share the honours and responsibilities of being the European Capital of Culture with Essen and Istanbul. The city’s motto will be: “The Borderless City”.1 Pécs’ historical importance as a regional centre began in Roman times. A Celtic settlement, which the Romans re-named Sopianae and developed, stood within what are now the boundaries of the city.2 It rose to prominence in the late third century A.D. when the province of Pannonia was divided into four parts: Pannonia Prima, Pannonia Secunda, Pannonia Valeria and Pannonia Savia. Sopianae became the administrative centre of Pannonia Valeria.3 Sopianae survived the end of the Western Roman Empire (476 A.D.), but the centre of the locality, during the Great Migration of the Peoples (fourth to ninth centuries), was displaced from the Roman town to the territory of the early Christian cemetery.4 Although many scholars assert otherwise, it is quite unlikely that in the Carolingian period the town belonged to the Frankish Empire, for the simple reason that its eastern border did not reach the Danube. Therefore it is hardly probable that the name Quinque Basilicae, that appears in the Conversio Bagoariorum et Carantanorum, refers to Pécs.5 Pécs continued to be the key town in this region in the Middle Ages. This successor to the ancient Sopianae was named Quinqueecclesiae in Hungarian documents written in Latin, 1 Professor Zoltan J. Kosztolnyik spent the fall of 1999 in Pécs as a visiting professor at the university of the town. He enjoyed very much the atmosphere of the town and his stay in Pécs, therefore I thought it would be apt to dedicate to his memory a paper that deals with a special question of the history of Pécs. I also would like to note that an earlier version of this paper had been presented in the session of the 42nd International Congress on Medieval Studies that was dedicated to the memory of professor Zoltan J. Kosztolnyik. 2 Ferenc Fülep, Sopianae. A római kori Pécs [Sopianae. Pécs in Roman times], Budapest, 1975. 3 Endre Tóth, “Sopianae: a római város, mint Pécs elıdje” [Sopianae: the Roman town as the ancestor of Pécs], in: Márta Font (ed.), Pécs szerepe a Mohács elıtti Magyarországon [The role of the town of Pécs in the period preceding the battle of Mohács], Pécs, 2001, 32. 4 László Koszta, “Pécs,” in: Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Early Hungarian historical lexicon (ninth to fourteenth centuries)], Gyula Kristó (ed. in-chief) – Ferenc Makk – Pál Engel (eds.), Budapest, 1994 (henceforth KMTL), 535; Tamás Fedeles, “Eine Bishofsresidenz in Südungarn im Mittelalter. Die Burg zu Fünfkirchen (Pécs).” Questiones Medii Aevi Novae, vol, 13, Palatium, Castle, Residence. Warszawa, 2008, 184. 5 Gábor Vékony, “A Karoling Birodalom délkeleti határvédelme kérdéséhez” [Contributions to the qeustion of the defence of the southeastern borders of the Carolingian Empire], Komárom Megyei Múzeumok Közleményei 2 (1986) 43–75; Tóth, Sopianae: a római város, 38. Fünfkirchen in German, and Pécs in the vernacular. It is also important to note that medieval Pécs was the seat of one of the wealthiest bishoprics of the Kingdom of Hungary. The diocese of Pécs was established by King Saint Stephen in 1009 and can be regarded as one of the oldest bishoprics of the Hungarian Kingdom.6 The city of Pécs also housed a cathedral and a collegiate chapter house which functioned as famous places of authentication. Furthermore one hospital and four convents belonging to various mendicant orders were also to be found in the city in the Late Middle Ages.7 One of the most important bishops of Pécs, William of Coppenbach (1361-1374), gained his fame because, in 1367, together with Louis I of Anjou, King of Hungary (1342-1382), he founded the first university of the realm. He then served as the first chancellor of this studium generale until his death in 1374.8 Following from the facts presented above, the urban development of Pécs was determined in the Middle Ages by the situation in which the city fell under the jurisdiction of the bishop and the cathedral chapter. Although the seigneurial lordship severely restricted the city’s autonomy, Pécs became a flourishing town. This was mainly due to the fact that relations between the ecclesiastical landlord and the citizenry of the town throughout the centuries had been harmonious. The citizens of Pécs, among whom, besides the Hungarians, 6 László Koszta, “Pécsi püspökség,” KMTL 538–539; Gergely Kiss, “A pécsi püspökség megszervezése és területi kiterjedése” [The organization of the bishopric of Pécs and its territorial extension], in: Márta Font (ed.), Pécs szerepe a Mohács elıtti Magyarországon [The role of the town of Pécs in the period preceding the battle of Mohács], Pécs, 2001, 53–68; see also Tamás Fedeles – Gábor Sarbak – József Sümegi (eds.), A középkor évszázadai (1009–1543). A Pécsi Egyházmegye története I. [The Centuries of the Middle Ages (1009–1543). A History of the Diocese of Pécs, vol. I.], Pécs, 2009. 7 György Tímár, “A szenttisztelet Pécsett a középkorban (patrocinium, titulus ecclesiae)” [The veneration of saints in Pécs in the Middle Ages (patrocinium, titulus ecclesiae)], in: Márta Font (ed.), Pécs szerepe a Mohács elıtti Magyarországon [The role of the town of Pécs in the period preceding the battle of Mohács], Pécs, 2001, 69–101; Tamás Fedeles, “A pécsi székeskáptalan személyi összetétele a hiteleshelyi oklevelek tükrében (1354-1437)” [The personnel of the cathedral chapter of Pécs as reflected by the charters issued by the chapter house as a place of authentication (1354-1437)], in: Márta Font (ed.), Pécs szerepe a Mohács elıtti Magyarországon [The role of the town of Pécs in the period preceding the battle of Mohács], Pécs, 2001, 103–137; Tamás Fedeles, A pécsi székeskáptalan személyi összetétele a késı középkorban (1354-1526) [The personnel of the cathedral chapter of Pécs in the Late Middle Ages (1354-1526)], Pécs, 2005. 8 For the latest discussion of the University’s medieval history see István Petrovics, “A középkori pécsi egyetem és alapítója” [The medieval university of Pécs and its founder], Aetas 20 (2005) no. 4, 29–40. With further bibliographical items. See also István Petrovics, William of Koppenbach and Valentin of Alsán, bishops of Pécs as diplomats. Forthcoming.; István Petrovics, “A pécsi egyetem kancellárjai: Koppenbachi Vilmos és Alsáni Bálint püspökök pályafutása” [The chancellors of the university of Pécs: the careers of Bishops William of Koppenbach and Valentin of Alsán], in: Tamás Fedeles - Zoltán Kovács - József Sümegi (eds.), Egyházi arcélek a pécsi egyházmegyébıl. Egyháztörténeti tanulmányok a pécsi egyházmegye történetébıl V. [Portraits of clerics from the diocese of Pécs. Essays on church history from the past of the diocese of Pécs, V], Pécs, 2009. 21–41. many ‘Latins’ and Germans9 can be found, dealt primarily with trade, and had strong economic contacts with Venice and Vienna.10 The city of Pécs in the early sixteenth century. (Planned and drawn by András Kikindai. In: József Sümegi (ed.), A pécsi egyházmegye ezer éve 1009-2009. Pécs, 2009, 75.) 9 In the eleventh and twelfth centuries the hospites (guests) arriving in Hungary came primarily from Flanders, North-France (Walloons), Lorraine and Lombardy. Since they spoke Romance languages, the Hungarian sources in the Latin language referred to them as Latini (Latins) or Gallici and Italici. They were followed in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries by Germans (Teutonici and Saxones). From the second part of the thirteenth century German ascendancy became obvious in most of the towns of the Hungarian Kingdom. 10 István Petrovics, “A középkori Pécs polgárai” [The citizens of medieval Pécs], in: Márta Font (ed.), Pécs szerepe a Mohács elıtti Magyarországon [The role of the town of Pécs in the period preceding the battle of Mohács], Pécs, 2001, 163–196. See also István Petrovics, Várostörténeti tanulmányok. Fejezetek Szeged, Pécs és Temesvár Hungary in the early fourteenth century As regards the political situation of the realm, it should be referred to that at the beginning of the fourteenth century, with the extinction of the former national ruling dynasty, the house of Árpád, Hungary entered a period of turmoil. Three rival candidates for the vacant Hungarian throne, each having a link with the Árpáds through the female line, aspired to obtain the crown: Charles Robert of Anjou from Naples; Wenceslas III, son of Wenceslas II, King of Bohemia, and grandson of Béla IV; and Otto of Wittelsbach from Bavaria. For a while Wenceslas III seemed to have a greater chance for acquiring rule over Hungary, but it was Charles, enjoying the support of popes Boniface VIII and Benedict XI together with that of the head of the Hungarian Church, who finally obtained the Hungarian crown and throne. After two previous coronations (1301, 1309) Charles I was finally crowned legally with the “Holy Crown of Saint Stephen” in Székesfehérvár in 1310, and accepted by the Hungarian nobility as the legitimate king of Hungary. Initially, he was not able to control the realm, since the country was, in fact, ruled by a dozen powerful landlords, the oligarchs or “little kings”. It took more than a decade for Charles I to liquidate the oligarchs, the last of which, John Babonić, was subdued in 1323. Only after having done so he could become the real ruler of the realm.11 középkori történetébıl [Urban historical studies. Chapters from the medieval history of Szeged, Pécs and Temesvár], Kéziratos PhD disszertáció/ Unpublished PhD dissertation, Szegedi Tudományegyetem/University of Szeged, 2005. 11 Pál Engel, The realm of St Stephen: A history of medieval Hungary, 895-1526, London and New York, 2001, 124–134. See also István Petrovics, “The kings, the towns and the nobility in Hungary in the Anjou era”, in: Noël Coulet-Jean-Michel Matz (eds.), La noblesse dans les territoires Angevins a la fin du Moyen Âge, Collection de l'École Française de Rome - 275. Rome, 2000, 431. Major trade and military routes in Hungary in the thirteenth-fourteenth centuries (After: Korai magyar történeti lexikon, 95.) The economic reforms of Charles I After liquidating the “little kings” Charles I introduced new measures by which he totally reorganised the economic life of the Hungarian Kingdom. Having decided not to keep the confiscated landed estates for himself but to redistribute them pro honore among his new aristocracy, Charles I had to find ways of increasing royal income by fostering industry and trade. The reforms he made in mining and coinage ultimately would affect Pécs’ main economic activity – trade. Mining Charles I’s most important measure was the reorganisation of the mining industry. He had to balance the interests of miners with those of land owners in a series of new policies. First the king decided not to withdraw the old privileges mining prospectors exercised, allowing them to open new shafts on any territory with or without the landlord’s consent. However, in order to secure the co-operation of the owners on whose land mines were being worked, or might be in the future, Charles I decided that beginning in 1327, one third of the “urbura”, that is the rent paid by the miners to the sovereign in respect of each mine, was to go to the lord of the domain. About the urbura it is necessary to understand that it was the king’s portion from the mining of precious metals which amounted to 1/10 for all gold and to 1/8 for all silver brought out of the ground. It is also important to note here that hitherto the piece of land, where precious metals had been found, had usually been expropriated by the king, while its lord was given land elsewhere in compensation. From 1327 onwards private landowners were also able to open mines, a strategy by which they could keep their own land and control prospecting, although they were required to sell the precious metal to the royal chamber at a fixed price. In other words, the king introduced a royal monopoly on gold and silver, thus creating a base for his monetary policy.12 The monetary reform At the beginning of the fourteenth century some thirty-five types of coin were in circulation in Hungary. As regards the coinage, silver coins remained predominant until the 1320s, as indeed they did everywhere in Europe with the exception of Italy.13 Charles I strove to replace these old coins by minting new gold florins on the Florentine model and smaller silver 12 Bálint Hóman, A Magyar Királyság pénzügyei és gazdaságpolitikája Károly Róbert korában [The finances and the economic policy of the Hungarian Kingdom during the reign of Charles Robert], Budapest, 2003 (Reprint), 153– 159; Franciscus Döry, Georgius Bónis and Vera Bácskai (eds.), Decreta regni Hungariae. Gesetze und Verordnungen Ungarns 1301-1457, Budapest, 1976 (henceforth DRH), 80–81; Engel, The realm of St Stephen, 155– 156. 13 The history of money in the Middle Ages falls into two distinct periods. The first, running from the seventh century to the twelfth, was an era of silver coins variously called pennies, deniers, denari, pfennings, or pennings depending on the language used. The second period, beginning in the thirteenth century was a much more complex era of large silver coins, which, since they were ‘great’ in comparison with the pennies, were variously called groschen, gros or grossi. It is important to note that gold disappeared in the Dark Ages, and was again used for currency in Western Europe only in the second period, which began, as stated above, with the thirteenth century. First of all there were the gold coins of the Italian trading-cities for international use in the Mediterranean world and later, with the fourteenth century conquest of Western Europe by gold coin, a variety of ‘national’ coinages like French écus, minted during the reign of Louis IX, or English nobles. Cf. Peter Spufford, Money and its use in medieval Europe. Cambridge University Press, 1988. coins. The gold content of the florin (forint in Hungarian) was the same as that of the fiorino d`oro (hence the name forint), but the coins were slightly heavier (3.56 g) because the alloy was less fine (23.75 carat). The picture shows that the avers depicted the Florentine lily, while on the revers Saint John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence, could be seen. The golden florin of Charles I This means that Charles I was the first ruler north of the Alps who issued a gold coin with a longevity of usage similar to its Florentine prototype. Hungarian golden florins were first seen in Moravia in 1326, and were to be minted for several centuries with a weight and quality almost unaltered. This reform produced monetary stability in Hungary, which, in the long run, had the most salutary effects on commerce and urban development. Gold bars must have continued to play an important role in the export trade, although they were not used on the domestic market. However, the monetary reforms of Charles I cannot be associated exclusively with the introduction of the golden florin in 1325. It was, in fact, only one of the king’s attempts done in order to improve the monetary system of the country, and it took Charles I all the time between 1325 and 1338 to find the overall solution.14 To appreciate fully the economic measures launched by Charles I in favour of the mining industry, it should be noted that at that time Hungary accounted for, approximately, one third of the total gold production of Europe. The most important gold mining towns were Aranyosbánya (modern-day Baia Arie in Romania), Nagybánya (modern-day Baia Mare in Romania), Felsıbánya (modern-day Baia Sprie in Romania) and Körmöcbánya (modern-day Kremnica in 14 Hóman, A Magyar Királyság pénzügyei, 75–140; Pál Engel, “A 14. századi magyar pénztörténet néhány kérdése” [Some questions of fourteenth century Hungarian monetary history], Századok 124 (1990), 25–91; Engel, The realm of St Stephen, 153–156; Csaba Tóth, “Pénzverés és pénzügyigazgatás (1000-1387)” [Coinage and financial administration (1000-1387)], in: András Kubinyi – József Laszlovszky – Péter Szabó (eds.), Gazdaság és gazdálkodás a középkori Magyarországon: gazdaságtörténet, anyagi kultúra, régészet [Economy and the management of economy in medieval Hungary: economic history, material culture, archaeology], Budapest, 2008, 163–184. Slovakia). In addition, the most important towns for silver mining were, Selmecbánya (modernday Banská Štiavnica in Slovakia), Besztercebánya (modern-day Banská Bystrica in Slovakia), Gölnicbánya (modern-day Gelnica in Slovakia) and Radna (modern-day Rodna in Romania). The exact volume of gold production in Hungary is not known. It has been argued that before 1500 Hungary supplied from 75 to 80 percent of the gold mined in Europe, this being one third of world production. While this is merely supposition, it is clear that the amount of gold produced in Hungary must have been very considerable.15 According to the only piece of evidence that we have, Elizabeth, the queen mother, when visiting Naples in 1343, took for ‘her expenses’ as the chronicler put it, 27,000 marks (6628 kg) of silver, 21,000 marks (5150 kg) of pure gold (corresponding to 1,449,000 florins but presumably in bars) and half a cart (garleta) of florins (corresponding to 2 to 300000 florins).16 This huge quantity of gold must have amounted to several years` total yield. We would probably be not too far from the truth in estimating the annual production of the Hungarian gold mines at from 1000 to 1500 kg.17 The chambers In Hungary the royal revenues were covered by the general term of ‘chamber’ (Latin: camera), which originally meant the king’s treasury, guarded in the early years at the royal residence in the town at Esztergom. The archbishop of Esztergom, head of the Hungarian church, had his see there. All royal revenues collected throughout the kingdom were brought there; for a long time it was the only place where coins were struck. It followed from this situation that the archbishop of Esztergom had the right to control, in the name of the realm, the quality of coins 15 István Petrovics, “Was there an ethnic background to the veneration of Saint Eligius in medieval Hungary?” in: Ladislaus Löb – István Petrovics – György E. Szınyi, Forms of Identity. Definitions and changes. Szeged, 1994, 77–87; Oszkár Paulinyi, “Magyarország aranytermelése a XV. század végén és a XVI. század derekán” [Hungary’s gold production in the late fifteenth century and in the middle of the sixteenth century], in: István Draskóczy – János Buza (eds.), Paulinyi Oszkár: Gazdag föld – szegény ország. Tanulmányok a magyarországi bányamővelés múltjából [Rich soil – poor country. Studies on the history of mining in Hungary], Budapest, 2005, 57–104. 16 “Domina igitur Elizabeth regina Hungarie mater regum predictorum post mortem regis Karoli habens devotionem visitandi sanctorum reliquias et apostolorum Petri et Pauli honorandi limina… de Wyssegrad in festo beatissime trinitatis anno domini milesimo tricentesimo quadragesimo tertio iter arripuit versus Italiam cum honesta familia et multitudine dominarum et nobilium puellarum, baronum militum et clientum cum multo et magno apparatu iuxta magnificentiam regiam ivit et processit habens secum pro expensa viginti septem millia marcarum puri argenti et decem septem millia marcarum purissimi auri. Dominus autem Lodowicus rex Hungarie filius suus misit post eam quattuor millia marcarum auri electi. Habuit etiam secum de florenis fere cum media garleta, de denariis vero parvis usque ad exitum regni multum.” Johannes de Thurocz, Chronica Hungarorum. vol. 1, Textus. Edited by Elisabeth Galántai and Julius Kristó, Budapest, 1985, 162–163. and in return could collect the pisetum, which was one tenth of the income deriving from the coinage. During the thirteenth century the Árpáds decentralized the administration of the royal revenues. Some parts of the country were given chambers of their own, which collected local revenues and struck coins from them. Henceforth, the word ‘chamber’ referred to a number of financial institutions all over the kingdom. The totality of them was identical to the royal treasury. The chamber of the diocese of Csanád, later transferred to Lippa (present-day Lipova, Romania), is mentioned from 1221 onwards, that of Szerém (Srem, Serbia) from 1253, that of Buda from 1255, and that of Slavonia (first at Pakrac, then later at Zagreb, both in present-day Croatia) from 1256. In the 1330s, as part of his reforms, Charles I created new chambers: at Körmöcbánya (present-day Kremnica, Slovakia), Szomolnok (present-day Smolník, Slovakia), later transferred to Kassa (present-day Košice, Slovakia), Szatmárnémeti (present-day Satu Mare, Romania), later transferred to Nagybánya (present-day Baia Mare, Romania), Nagyvárad (present-day Oradea, Romania), Pécs and one in Transylvania. Each chamber was in charge of a certain number of counties, which were the smaller administrative units of the realm. Each was directed by a businessperson called a ‘chamber count’ (comes camerae). Prior to 1270, this position was held by a Jew or Moslem, but then they were replaced with a series of German and Italian merchants and even a few Hungarian urban burghers. The chamber count had the right to administer the royal revenues of his chamber according to certain well defined conditions and in return for a fixed sum. Although the realm was divided into 10 chamber districts in the 1330s, a chamber count could farm more than one district at the same time. The chamber counts were in charge of all those financial resources that were regarded as royal property: besides coinage and the gold mines the most important were the salt monopoly, the tax of the towns and the free villages and the toll on foreign trade called the ‘thirtieth’ (tricesima). In some areas, and over time, Charles I had alienated parts of the royal domain and given them to nobles to buy their support. These honours controlled by barons, counts and castellans were no longer included among the chambers` administrative responsibilities.18 17 Paulinyi, Magyarország aranytermelése, 60; Engel, The realm of St Stephen, 155–156. Hóman, A Magyar Királyság pénzügyei, 193–251; Engel, The realm of St Stephen, 153–155; Márton Gyöngyössy, “Pénzverés és pénzügyigazgatás (1387-1526)” [Coinage and financial administration (1000-1387)], in: András Kubinyi – József Laszlovszky – Péter Szabó (eds.), Gazdaság és gazdálkodás a középkori Magyarországon: gazdaságtörténet, anyagi kultúra, régészet [Economy and the management of economy in medieval Hungary: economic history, material culture, archaeology], Budapest, 2008, 185–187. 18 The chambers: financial administration of Hungary in the fourteenth century (Hóman, A Magyar Királyság pénzügyei, 288–289) As it has already been pointed out, the realm was divided, theoretically, into ten chamber districts. Nevertheless, we can count, in fact, only with eight, since the one in Szerém was united with the chamber in Pécs, and the chamber in Esztergom was united with the one in Buda. Unfortunately, very few documents have survived that prove the existence of the chamber in Pécs: it is highly probable that it did not work continuously in the later Middle Ages. One of the documents reveals that the united chamber of Pécs and Szerém was farmed out in 1342 for 1500 marks.19 Surprisingly enough, three years later, i.e. in 1345, the amount for which the same 19 Hóman, A Magyar Királyság pénzügyei, 261, a summary with incorrect date. The document is published in extenso in DRH vol. 2, 106–115. “Nos Karolus dei gratia rex Hungarie memorie commendantes tenore presentium quibus expedit universis significamus, quod nos prelatorum et baronum regni nostri voto unanimi et de consilio chamber was farmed out reached 3300 marks.20 This shows that the chamber of Pécs grew in importance after the death of Charles I. It is most interesting, since it soon turned out that the task of collecting taxes and that of coinage got separated from each other at such chambers where there were no working gold mines. Medieval Pécs was one of the places where gold mines did not exist. How, then, could minting continue in Pécs? Some scholars believe that raw material, evidently silver, was carried to Pécs from the mines of Bosnia. This assertion can be argued since the chamber counts had no jurisdiction over the territories of the banates, i.e. territories held by the Hungarian Kingdom south of the Sava River or at the Lower Danube. It is equally important to stress that the significance of the banates grew only in the fifteenth century, because of their increasing military role resulting from the Ottoman advance. It is more probable that the “raw material” that was used for minting in Pécs came from the tax named “chamber`s profit” (lucrum camerae) and paid by the serfs.21 In order to support this assertion we should refer to the fact that the territory which belonged to the PécsSzerém chamber had the highest population density within the borders of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary.22 eorundem, considerata sagaci industria magistri Endre Chempeliny, comitatus camerarum nostrarum de Syrmia et de Quinqueecclesiis cum omnibus comitatibus, districtibus, civitatibus, villis et opidis, qui et que ab antiquo ad easdem cameras dinosscuntur pertinuisse, scilicet cum comitibus Syrmiensi, Bachyensi, de Wolkow et de Bodrugh, item de Baranya, Symigiensi, Tholnensi et Zaladiensi eidem magistro Endre pro mille et quingentis marcis, partim in florenis seu aureis denariis camere nostre Bude cusis et cudendis, partim vero in integris camere nostre monetis annorum preteriti, tertii, quarti et presentis, per totum nostrum uniformiter discurrendis et per preteriti anni modum tam per ipsum, quam per alois regni nostri camerarios ampliandis, nobis in terminis infrascriptis persolvendis, anno domino millesimo CCCoXL mo secundo a data presentium per anni circulum simulcum decimis archyepiscopalibus dedimus iterato et locavimus ad exercendum, procurandum et tenendum isto modo: …” DRH vol. 2, 107. 20 Hóman, A Magyar Királyság pénzügyei, 261–268. (With incorrect date.) The latest edition of the document is in DRH vol. 2, 118–123. “[N]os Lodouicus dei gratia rex Hungarie tenore presentium significamus, quibus expedit universis, quod nos considerata industria magistri Nicolai dicti de Zathmar civis Budensis, fidelis nostri comitatus camerarum nostrarum Syrimiensis et Quinqueeclesiensis, prelatorum et baronum regni nostri consilio prematuro, cum omnibus comitatibus, districtibus, civitatibus et villis, que ab antiquo ad easdem cameras pertinuisse dinosscuntur, scilicet cum comitatibus Syrimiensi, Bachyensi, de Wolko et de Bodrugh, item de Baranya, Symigiensi, Tholnensi et Zaladiensi eidem magistro Nicolao dicto de Zathmar pro tribus milibus et trecentis marcis, partim in florenis seu aureis denariis camere nostre Bude cusis et cudendis, partim vero in grossis novis camere nostre anno in presenti fabricandis, nobis in terminis infrascriptis persolvendis anno domini Mo CCCmo XLmo quinto a data presentium per anni circulum simul cum decimis archiepiscopalibus locavimus procurandum isto modo. ...” DRH vol. 2, 118–119. 21 András Kubinyi, “A középkori körmöcbányai pénzverés és történeti jelentısége” [Coinage in medieval Körmöcbánya and its historical significance], in: Emlékezés a 650 éves Körmöcbányára. A Magyar Numizmatikai Társulat ünnepi ülése a Magyar Tudományos Akadémián 1978. október 26-án Körmöcbánya várossá nyilvánításának 650. évfordulója alkalmából [Commemorative session of the Association of Hungarian Numismatists at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on 26 October 1978 on the occasion that Körmöcbánya was founded 650 years ago], Magyar Numizmatikai Társulat, 1978, 15–16. 22 András Kubinyi, “A Magyar Királyság népessége a 15. század végén” [The population of the Hungarian kingdom at the end of the fifteenth century], Történelmi Szemle 38 (1996), 157–158. Written sources about the administration of the united chamber of Pécs-Szerém, mostly contracts and charters, give data about the activity of four counts.23 The first, Endre Chempeliny, who appears in the contract from 1342, administered the chamber at the end of Charles I’s reign.24 The other three, Nicolaus Szatmári (Nicolaus dictus de Zathmar), a count named Lóránd (Lorandus), and Jacopo Saraceno (Jacobus dictus Sarachen) administered the chamber of PécsSzerém after the death of Charles I. Nicolaus Szatmári is mentioned in a charter as the chamber count of Pécs-Szerém already in 1343.25 Written sources show that after a year (1344), when Lorandus acted as a chamber count, in 1345 King Louis I entered into a contract by which he entrusted Nicolaus with the administration of the Pécs-Szerém chamber.26 Unfortunately, we have no documentary evidence informing us when Nicolaus Szatmári finished his activities as a chamber count. In 1352 a new person appears at the head of the Pécs-Szerém chamber. He is Jacopo Saraceno, an Italian, who having arrived in Hungary, first settled in Buda and became a citizen of that town. He appears in the sources variously as count of the chamber of Pécs-Szerém and as the head of minting of the realm until 1379.27 From the period that lasts from the late fourteenth century until the fall of the independent Hungarian Kingdom (i.e. until 1526), with the exception of a few years during the reign of King Sigismund (1387-1437),28 no documents and coins have survived that could prove that coins were minted in Pécs. Charles I’s legacy To sum up: both the promotion of mining and the regulation of the country’s monetary system were the work of Charles I, the first Hungarian king from the Angevin (Anjou) Dynasty. His monetary reforms proved to be of lasting importance. First of all, he ended, once and for all, 23 István Hermann, Finanzadministration in der zweiten Hälfte des 14. Jahrhunderts in Ungarn. Budapest, 1987, 84. The most recent study on the subject is: Boglárka Weisz, “A szerémi és pécsi kamarák története a kezdetektıl a XIV. század második feléig” [The History of the Chambers of Szerém and Pécs from the Beginnings up to the Second Half of the Fourteenth Century], Acta Universitatis Szegediensis. Acta Historica CXXX , Szeged, 2009, 3352. Since this study was published after the manuscript of the present volume had gone to press, I was, unfortunately, not able to to take into consideration the results of Weisz’s research. 24 DRH vol., 2, 107. See also footnote no. 19 above. 25 Magyar Országos Levéltár. Mohács elıtti győjtemény [Hungarian National Archives, Collection of charters issued before Mohács (1526)], 3596. 26 DRH vol. 2, 118–123. 27 András Kubinyi, “Ernuszt Zsigmond pécsi püspök rejtélyes halála és hagyatékának sorsa (A magyar igazságszolgáltatás nehézségei a középkor végén” [The mysterious death of Sigismund Ernuszt, Bishop of Pécs and the fate of his legacy], Századok 135 (2001), 339. With further bibliographical items. the anarchy in minting practices that characterized the reign of the national ruling dynasty, the house of Árpád. He abolished the practice of issuing new money yearly, which went hand-inhand with a forced return of the old coins to the treasury, and beginning in 1323, and permanently after 1336, he issued silver coins with a constant value. The treasury’s resulting loss was compensated for by the introduction of a new tax aptly called “the chamber’s profit” which was collected from each serf household. The reform of the financial administration was equally important, which from the point of view of the history of Pécs proved especially to be of great importance, since it resulted in the establishment of a chamber in the town. Epilogue Louis I (the Great) of Hungary (in Hungarian named as I. (Elsı) or Nagy Lajos, in Polish called: Ludwik Węgierski, in Croatian: Ludovik I) was Charles I’ successor and, as well as, King of Hungary, Croatia, Dalmatia etc. from 1342, and King of Poland from 1370. He was one of Hungary’s most active monarchs of the Late Middle Ages extending her territory to the Adriatic and securing Dalmatia, with parts of Bosnia and Bulgaria, within the Hungarian crown. He spent much of his reign making sometimes successful war on the Republic of Venice, and fruitlessly competing for the throne of Naples. As regards his monetary policy he issued a few new types of pennies (denarii) until 1346. Between 1346 and 1357 he resumed the old practice of cropping and re-minting of coins, most probably in order to finance his military campaigns. Then, in 1358 a new type of high-quality silver penny appeared. This is named by scholars as: the coin “with the head of a Saracen”. This coin can evidently be associated with one of the most influential chamber counts, magister Jacobus dictus Sarachen and showed his family symbol, a Saracen (that is a Negro) head. (The members of the Szerecsen family, Jacopo and Giovanni Saraceno had come to Hungary from Padua, and became burghers of Buda.) This type of silver penny, which had a constant value, was minted until 1372, when it was replaced by another type. This new coin appeared in 1373: it was struck with the figure of Saint Ladislaus, King of Hungary (1077-1095). The figure of Saint Ladislaus appeared originally only on golden coins but with this 1373 issue later such a type of silver coins were also in circulation. Around 1355 Louis I ceased the minting of banal pennies (denarii banales) in Slavonia and that of the pennies of 28 Kubinyi, A középkori körmöcbányai pénzverés, 23. Buda.29 The minting of money was a royal prerogative in medieval Hungary. The minting of autonomous coins, as in the case of the banal pennies of Slavonia and those of Buda between 1311 and 1355, was an exceptional situation. All these developments can be seen effectively as a continuation of the policies of Charles I. 29 Cf. Lajos Huszár, A budai pénzverés története a középkorban [The history of minting in Buda in the Middle Ages], Budapest várostörténeti monográfiái XX. Budapest, 1958, 42–64. See also Engel, The realm of St Stephen, 186–188.