Fast stocks, fast money how to make money investing in new issues and small-company stocks

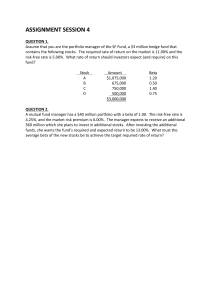

advertisement