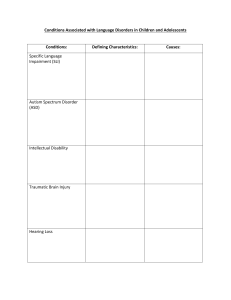

[Downloaded free from http://www.jisprm.org on Thursday, August 20, 2020, IP: 114.108.251.132] CHAPTER 3: PHYSICAL AND REHABILITATION MEDICINE (PRM) - CLINICAL SCOPE 3.2 Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine – Clinical Scope: Specific Health Problems and Impairments Sam S. H. Wu1,2,3, Chulhyun Ahn1 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, Geisinger Musculoskeletal Institute, Geisinger Health System, Danville, PA, USA, 2Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, USA, 3Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ, USA 1 IntroductIon neurologIcal condItIons The World Health Organization estimates that there will soon be 1 billion persons with disabilities suffering from functional deficits. The financial impact due to lost productivity compounded by the substantial healthcare costs associated with these disabilities will amount to staggering tens of trillions of dollars. A solution to this global vicissitude is to find pathways for the optimization of these individuals’ function to provide the best chance for them to return to being productive members of society. Because physicians specializing in physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM – in some countries, also known as physiatrists) are trained to be restorers of function, they are indeed a major stakeholder in this process. Stroke In keeping with the epithet “quality of life medical specialty,” the physiatric clinical practice focuses on enhancing an individual’s functional status and lessening his/her disability through prevention, diagnosis, and nonsurgical management of disorders commonly associated with functional deficits: most notably, disorders affecting neurological, musculoskeletal, and cardiopulmonary systems. Commonly managed conditions in the physiatric practice include stroke, spinal cord injury, brain injury, multiple sclerosis, neuropathies, neuromuscular disorders, orthopedic conditions, amputation, vascular problems, trauma, work-related injuries, cardiac disorders, pulmonary conditions, malignancy, and burns. This subchapter will discuss the more common health problems and impairments encountered by persons with disabilities. The selection of these conditions is not meant to be all-inconclusive. The tools used in diagnosing some of these conditions are discussed in the subchapter on diagnostic tools. Moreover, the treatments of some of these conditions are discussed in the subchapter on interventions. Access this article online Quick Response Code: Website: www.jisprm.org DOI: 10.4103/jisprm.jisprm_10_19 A cerebrovascular accident, also known as stroke, entails rapidly developing focal or global cerebral dysfunction due to cerebrovascular insufficiency or intracranial hemorrhage. The incidence of stroke is approximately 795,000 cases a year in the US alone, of which about 610,000 are new strokes and the remaining 185,000 are recurrent ones.[1] Approximately 85% of the strokes are ischemic and the rest are hemorrhagic. Stroke is estimated to account for 13% of all causes of death worldwide.[2] The resultant neurological deficits vary depending on the cerebral territory affected. Common clinical presentations include but are not limited to decreased muscle strength, incoordination, spasticity, altered sensation, aphasia, dysarthria, dysphagia, apraxia, neglect, seizure, impaired bowel/bladder control, and ataxia. These impairments lead to impaired functional mobility such as balance loss, ambulatory dysfunction, and difficulty with transfers; deficits in daily activities of living such as dressing, bathing, eating, grooming, and toileting; and difficulty with speech, language, cognition, and swallowing. Nearly half of all strokes have thrombotic etiology with perfusion failure distal to the site of vascular occlusion or severe stenosis. Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco use, a sedentary lifestyle, diabetes, and hypercoagulable states are risk factors for vascular thrombosis. Transient ischemic attack is a brief episode of neurological dysfunction without evidence of infarction and it commonly precedes thrombotic strokes. Address for correspondence: Sam S. H. Wu, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, Geisinger Musculoskeletal Institute, Geisinger Health System, 64 Rehab Lane, Danville, PA 17821, USA. E-mail: samshwu@hotmail.com This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms. For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com How to cite this article: Wu SS, Ahn C. 3.2 Physical and rehabilitation medicine – Clinical scope: Specific health problems and impairments. J Int Soc Phys Rehabil Med 2019;2:S29-34. © 2019 The Journal of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine | Published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow S29 [Downloaded free from http://www.jisprm.org on Thursday, August 20, 2020, IP: 114.108.251.132] Wu and Ahn: PRM clinical scope Table 1: The Rancho Los Amigos Levels of Cognitive Function Scale Rancho Los Amigos Levels of Cognitive Function Scale Levels Level I II III IV V VI VII VIII Response No response to visual, verbal, tactile, auditory, or noxious stimuli Generalized response Localized response Confused and agitated Confused and inappropriate Confused and appropriate Automatic and appropriate Purposeful and appropriate The second most common type of cerebrovascular accident is embolic stroke which represents about 26% of all strokes. The emboli are typically of cardiac origin although microemboli that dislodge from cerebrovascular thrombi could occur. Impaired atrial motility in the setting of atrial fibrillation is a significant risk factor for mural thrombi formation. Cardiac emboli are also commonly produced in the presence of rheumatic heart disease, bacterial/marantic endocarditis, prosthetic heart valves, and vegetations at heart valves. Usually, the neurological deficits are acute and can be accompanied by seizure. Lacunar strokes result from occlusion of small arteries and are estimated to account for 13% of all strokes. Higher cortical functions are typically not affected in lacunar strokes. Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage often presents with acute-onset headache, vomiting, and impaired consciousness along with other focal neurological deficits. Putamen is the most common location of hemorrhage. Hemiplegia results from compression of adjacent internal capsule. Other common locations of hemorrhage are thalamus, pons, cerebellum, and cerebral hemisphere. Subarachnoid hemorrhage typically stems from rupture of saccular aneurysms and less commonly from ruptured arteriovenous malformations. Severe headache, nuchal rigidity, and altered level of consciousness are frequent clinical manifestations of subarachnoid hemorrhage. There is increased risk of recurrent bleeding Brain injury Brain injury results from external forces, hypoxia, or toxic substances. Brain damage resulting from vascular occlusion or rupture is called stroke and is not usually included in the category of brain injury which is further classified as traumatic and nontraumatic. Causes of traumatic brain injury include motor vehicle accidents, violence, falls, and sports injury. Each year, approximately 10 million traumatic brain injuries are reported to occur worldwide.[3] The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury appears to follow similar patterns globally. Approximately 80% of traumatic brain injuries are classified as mild while 10% are moderate and another 10% S30 are severe. The pathophysiological findings in traumatic brain injury include cortical contusion, diffuse axonal injury, focal hemorrhage such as epidural or subdural hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage as well as secondary cytotoxic and vasogenic edema that follow the initial insult. Dependent on the type, severity, and location of the injury, the patients present with a variety of focal or global neurological deficits. The Rancho Los Amigos Levels of Cognitive Function Scale is an eight-level scale that focuses on cognitive and behavioral recovery after traumatic brain injury [Table 1].[4] Levels I through III represent coma, vegetative state, and minimally conscious state, respectively. Once a patient emerges out of posttraumatic amnesia, he/she is at level IV or above. As the levels go up, the confusion and agitation subside and the patient’s behavior becomes more purposeful. Spinal cord injury The incidence of spinal cord injury ranges from 12.1 to 57.8 cases per million people worldwide. [5] The risk of spinal cord injury is higher in males and in 30–50 years old individuals. Motor vehicle accidents are the leading cause of spinal cord injury in developed countries while falls are the most frequent cause in developing countries. Other causes include violence, sports injuries, spinal tumors, infections, ischemia due to vascular compromise, radiation exposure, multiple sclerosis, and nutritional deficiencies. The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale is commonly used to assess the extent and severity of spinal cord injuries. The overall neurological level of injury as defined by ASIA Impairment Scale is the more rostral of motor or sensory levels of injury. The clinical manifestation of patients with the same neurological level of injury may differ significantly depending on the degree and extent of the injury. The ASIA scale captures the degree of neurological impairment with a scale from A through E, with A being complete injury and E complete recovery following spinal cord injury. The functional impairment and medical complications due to spinal cord injury include weakness, gait dysfunction, sensory deficits, neurogenic bowel and bladder, pressure ulcers, muscle spasticity, joint contractures, hygiene problems, osteoporosis, degenerative joints, musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain, autonomic dysfunction, respiratory insufficiency, and sexual dysfunction. These complications can all contribute to difficulties with functional mobility, and activities of daily living, and to morbidity and mortality. Musculoskeletal dIsorders Neck problems The incidence of neck pain, also known as cervicalgia, is estimated to be from 10% to 20% of the general population. The lifetime prevalence could be up to two-thirds of the population.[6] The clinical manifestation of cervical pain often reflects the underlying problem. An acute-onset cervicalgia following a traumatic event without neurological deficits The Journal of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine ¦ Volume 2 ¦ Supplement 1 ¦ June 2019 [Downloaded free from http://www.jisprm.org on Thursday, August 20, 2020, IP: 114.108.251.132] Wu and Ahn: PRM clinical scope is most commonly due to neck muscle or tendon strain, or ligament sprain. Subacute cervicalgia accompanied by neurological changes radiating to the upper extremity raises the concern for cervical radiculopathy compromising one or more cervical nerve roots. Involvement of the cervical intervertebral discs can lead to cervicalgia elicited by lifting heavy objects, coughing, or sneezing. Progressive cervicalgia with insidious onset accompanied by systemic manifestations raises the possibility of a slowly growing tumor. Cervical myelopathy due to congenital or acquired cervical stenosis can cause gait dysfunction with or without leg weakness and impaired coordination of the upper extremities. Low back problems Low back pain is the second most common complaint for physician visit after upper respiratory infection. The incidence and prevalence of low back pain in the general population are reported to be 5% and 23%, respectively. The lifetime prevalence of low back pain could be up to 85%.[7] Low back pain is one of the most common conditions encountered by PRM physicians. This condition is often generated by degenerative disc changes, facet arthropathy, paraspinal muscle and tendon strain, or vertebral ligament sprain. These entities are associated with excessive physical activities that increase stress and strain at the spine. Patients frequently report chronic pain at low back that may radiate to gluteal regions. Impingement of spinal nerve roots due to disc herniation, foraminal stenosis or facet hypertrophy can produce radicular symptoms in the lower extremities. In severe central lumbar spinal canal stenosis, patients may develop neurogenic claudication. Fractures Fracture refers to compromise in the continuity of the bony tissue. Fractures usually originate from high tensile or shear stress due to a traumatic impact. However, in the presence of underlying conditions such as bone tumor, osteoporosis, or osteogenesis imperfecta that undermine bony strength or resilience, pathologic fracture can occur on minor impact. Fractures of femoral neck, vertebral bone, pelvis, facial bones, and humerus are especially frequent in elderly people prone to falls. Stress fractures are very small disruption of the cortical surface produced by repeated submaximal stress over time. It is common in weight-bearing bones such as tibia, navicular bone, and metatarsal bones in athletes. Arthritis The hallmark of osteoarthritis, also known as degenerative joint disease, is degeneration of articular cartilage. Secondary bony changes ensue including generation of osteophytes, subchondral eburnation, and cyst formation. Commonly involved joints are the hip, knee, cervical/lumbar vertebra, interphalangeal joints of the hand, and first carpometacarpal/ tarsometatarsal joints. Pain and joint stiffness are common clinical presentations. Rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by chronic inflammatory changes primarily in the joints but sometimes in other organ systems as well. Nonsuppurative proliferative synovitis and pannus formation give rise to joint erosion and destruction. Joint involvement is typically symmetric and polyarticular and can be accompanied by systemic manifestations such as low-grade fever, malaise, and weakness. Musculoskeletal disorders of the limbs Musculoskeletal disorders can present as joint pain, muscle weakness, decreased range of motion, and altered muscle tone in the extremities. Trauma is a causative factor of acute injury, but more commonly, musculoskeletal problems in the upper and lower limbs result from chronic degenerative changes in the bony and soft tissues. Common bone problems include fractures, arthritis, tumors, osteomyelitis, and genetic disorders. Tendons can develop tendinopathy, tendinitis, partial or complete rupture, impingement, and snapping. Ligaments could undergo partial or complete rupture and sprain. Joint cartilage and menisci could sustain traumatic as well as degenerative changes. Muscle pathologies include muscle strain, tear, impingement, ischemia, inflammation, infection, and necrosis. Musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limbs Rotator cuff impingement is the most common cause of shoulder pain. Impingement of the supraspinatus tendon under the acromion and greater tuberosity is frequently observed in rotator cuff impingement. It can progress to rotator cuff tendinopathy and tear. Adhesive capsulitis restricts glenohumeral range of motion and causes shoulder pain. Degenerative joint disease of the shoulder joint involves destruction of the glenohumeral joint resulting in pain and limited range of motion. Common conditions in the elbow region include medial epicondylitis which is caused by repetitive valgus stress to the elbow and lateral epicondylitis which is caused by repetitive wrist extension and forearm supination. Medial epicondylitis is known as golfer’s elbow while lateral epicondylitis is known as tennis elbow. Ulnar and radial collateral ligament sprain produce pain localized to medial and lateral aspect of the elbow, respectively, as well. De Quervain’s tenosynovitis arises from tenosynovitis of the tendons and sheaths of the first wrist compartment and produces pain and tenderness on the radial side of the wrist. Ganglion cysts which are synovial fluid-filled cystic masses commonly found on the dorsal or volar aspect of the wrist may generate pain on ranging the wrist or pressure. Stenosing tenosynovitis, commonly known as trigger finger, causes finger locking in a flexed position. Musculoskeletal disorders of the lower limbs Patients with greater trochanteric hip bursitis report lateral hip pain and have difficulty lying on the affected side. This condition is due to inflammation of the bursa over the greater trochanter and is associated with conditions that produce muscle imbalance and reduced flexibility. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head is precipitated by interruption of vascular supply to the femoral head and leads The Journal of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine ¦ Volume 2 ¦ Supplement 1 ¦ June 2019 S31 [Downloaded free from http://www.jisprm.org on Thursday, August 20, 2020, IP: 114.108.251.132] Wu and Ahn: PRM clinical scope to hip pain of insidious onset that worsens with weight bearing and hip range of motion. Use of steroid and alcohol increases the risk of avascular necrosis. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis is a hip condition where the head of the femur slips off the neck of the femur. This condition occurs during periods of rapid growth in adolescents who present with hip pain, stiffness, and often instability. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) sprain or tear is one of the most frequent knee injuries. It often occurs during sports activities that involve sudden deceleration and changes in directions. Instability and effusion of the knee joint are common after ACL injury. Patellofemoral syndrome, also known as biker’s knee or runner’s knee, is a broad term denoting anterior knee pain around the patella. The pain is typically worse with negotiating stairs or riding bicycles as the contact pressure between the patella and femur increases. Lateral ankle sprain is the most common ankle sprain and usually takes place on inversion of a plantar-flexed foot. Anterior talofibular ligament is the most frequently involved ligament in lateral ankle sprain followed by calcaneofibular ligament and posterior talofibular ligament. Plantar fasciitis entails increased fascial tension and inflammation of the plantar fascia and is a common cause of plantar heel pain. Tight Achilles tendon, pes cavus and planus, and bone spurs increase the risk of plantar fasciitis. Amputation Existing data suggest that 185,000 individuals are estimated to undergo an amputation of upper or lower extremity in the US each year. There were 1.6 million individuals with one or more limb amputations in the US in 2005.[8] Upper extremity amputees account for <30% of all individuals with amputations in the US. Trauma represents 90% of the etiology for all upper limb amputations. In the United Kingdom, there were 42,294 major lower limb (22,645 above knee and 19,658 below knee) and 52,525 minor lower extremity amputations between 2003 and 2013.[9] In Norway, the population prevalence of adult-acquired major upper limb amputation was estimated at 11.6/100,000 adults. The patients were predominantly men with traumatic, unilateral, and distal amputations acquired at a young age.[10] Amputations due to vascular conditions represent the greatest portion (82%) of lower extremity amputations followed by amputations secondary to trauma (16%), malignancy (0.9%), and congenital deformity (0.8%). Diabetes is a major risk factor of lower limb amputation along with hypertension and smoking. Congenital limb deficiencies are slightly more common in the upper extremities (58%) with left short transradial amputation being the most common. Teratogenic agents such as thalidomide and amniotic band syndrome are associated with congenital limb deficiency. S32 According to the level of amputation, the types of upper extremity amputations include finger amputation, wrist disarticulation, transradial amputation, elbow disarticulation, transhumeral amputation, shoulder disarticulation, and forequarter amputation. Finger amputation is the most frequent upper extremity amputation (78%) followed by transradial and transhumeral amputations. The levels of lower limb amputations include toes, midfoot, ankle, transtibial, knee, transfemoral, hip, and hemipelvectomy. Toe amputation accounts for 31.5% of lower limb amputations closely followed by transtibial (27.6%) and transfemoral amputations (25.8%). neuroMuscular dIsorders Neuromuscular disorders encompass a diverse group of disorders primarily affecting peripheral nervous system and skeletal muscles. Neuropathic disorders include motor neuron diseases, various entrapment neuropathy of peripheral nerves, polyneuropathy, and neuromuscular junction disorders. The etiology of neuropathy is diverse and includes inherited or sporadic genetic derangements, metabolic disorders, toxins, infection, autoimmunity, and mechanical stress. Neuropathic disorders present with variable extent of muscle weakness, sensory changes, and spasticity. Neuromuscular junction disorders stem from inefficient transmission of electrochemical signals across the synapse between motor neuron and the skeletal muscle, either due to decreased release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic terminal (e.g., Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome and botulism) or impaired action of neurotransmitter at the postsynaptic membrane (e.g., myasthenia gravis). The result is variable weakness in trunk, extremities, respiratory muscles, and bulbar muscles. Myopathic disorders have equally diverse origin and can be classified as dystrophic, myotonic, congenital, or myopathic. The Duchenne and Becker’s myopathies are representative of dystrophic myopathy and result from absence or low-level presence of dystrophin gene, respectively. The dystrophic myopathies manifest as skeletal muscle weakness of variable onset, progression, severity, and extent resulting in impaired mobility and activities of daily living. The cardinal symptom of myotonic myopathies is delayed relaxation of skeletal muscles after contraction. The myopathies are exemplified by polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and inclusion body myositis. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis result in proximal muscle weakness with myalgia and can have autoimmune, infectious, or malignant causes. Dermatomyositis has additional cutaneous manifestations. Patients with inclusion body myositis usually develop painless weakness in the distal as well as proximal muscles. cardIac dIsorders, pulMonary dIsorders Debility, impaired endurance, and decreased strength associated with cardiac disorders and pulmonary disorders are the targets of cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation, respectively. The Journal of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine ¦ Volume 2 ¦ Supplement 1 ¦ June 2019 [Downloaded free from http://www.jisprm.org on Thursday, August 20, 2020, IP: 114.108.251.132] Wu and Ahn: PRM clinical scope Candidates for pulmonary rehabilitation programs include individuals with obstructed airway disease and restrictive lung disease. Examples of obstructive airway disease are chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and cystic fibrosis. Causes of restrictive pulmonary disease include intrinsic lung disease with increased lung tissue stiffness, extrinsic lung disease involving increased chest wall stiffness, neuromuscular disease, and cervical spinal cord injury that result in respiratory muscle weakness and thoracic spine deformities that limit chest wall expansion. The objective of cardiac rehabilitation is to promote patient’s overall fitness by improving cardiovascular fitness. Cardiovascular conditions that could benefit from cardiac rehabilitation include coronary artery disease, angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy, postcoronary artery bypass graft, postheart transplantation, and peripheral vascular disease. cancer Patients who are in the midst of battling cancer are often debilitated and are predisposed to develop muscle atrophy, joint contractures, deconditioning, debilitating pain, neuropathies, and orthostatic hypotension. Furthermore, individuals who survive cancer frequently manifest residual symptoms as a result of local and systemic effect of cancer burden itself, or interventions for cancer such as surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy. Conditions amenable to PRM intervention are tumor-related lymphedema, peripheral neuropathy resulting from the use of chemotherapeutic agents, and decreased range of motion stemming from radiation-induced fibrosis. pedIatrIc condItIons Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common cause of childhood disability. The prevalence of CP can range from 1.5 to more than 4 per 1000 children worldwide.[11] CP is a static encephalopathy meaning that although a patient’s functions may change over time, the underlying brain lesion is nonprogressive. CP is primarily a neuromotor deficit with associated cognitive and sensory problems. CP is currently classified into spastic CP, dyskinetic CP, and mixed Type CP. Spastic CP accounts for 75% of CP. Subgroups of spastic CP consists of spastic monoplegia, spastic diplegia, spastic triplegia, spastic tetraplegia, and spastic hemiplegia. Dyskinetic CP is associated with athetosis, chorea, choreoathetosis, dystonia, and ataxia. Independent sitting by the age of 2 years is a good prognostic indicator for ambulation. Spina bifida is the second most common cause of childhood disability. Spina bifida is a neural tube defect. Neural tube defect is categorized into anencephaly, encephalocele, and spina bifida. The incidence of neural tube defects varies greatly around the world from 0.6–3 to 4/1,000 live births.[12] Spinal bifida is classified into spina bifida occulta (no cystic sac formation; no neurologic deficit) and spina bifida cystica. Subgroups of spina bifida cystica are meningocele (cystic sac containing spinal fluid and meninges; neurologic signs can be normal) and myelomeningocele (cystic sac containing spinal fluid, meninges, and spinal cord; neurological deficit includes motor paralysis, sensory deficits, neurogenic bowel, and bladder with associated Arnold–Chiari Tye II malformation, hydrocephalus, and tethered spinal cord). Lower levels of spinal lesions in spina bifida patients are associated with higher levels of motor functions. Scoliosis is classified into functional scoliosis and structural scoliosis which consist of subgroups of congenital, idiopathic, acquired, and secondary. Functional scoliosis is reversible whereas structural scoliosis is not. The majority of scoliosis is idiopathic scoliosis. Secondary scoliosis can be caused by neuromuscular disease or connective tissue disease. Cobb’s angle is used to determine the angle of the spinal curve. Vital capacity is the most common abnormality on pulmonary function test as the spinal curve progresses past 50°. In idiopathic scoliosis, observation is indicated when the spinal curve is 1°–20°, bracing when 21°–40°, and surgery when >40°. For scoliosis due to neuromuscular diseases, observation is indicated when the spinal curve is 1°–20°, and surgery when >20°. However, bracing or surgery may be considered sooner if there is an accelerated progression in the spinal curve. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is the most common connective tissue disease in children with variable prevalence worldwide from 0.038 to 3.7/1000 population.[13,14] JRA has an onset of <16 years with arthritic symptoms lasting at least 6 weeks. JRA is categorized into polyarticular rheumatoid factor negative, polyarticular rheumatoid factor positive, pauciarticular type I, pauciarticular type II, and systemic onset. Sacroiliitis is associated with pauciarticular type II while iridocyclitis is associated with both pauciarticular type I and type II. Antinuclear antibodies are associated with polyarticular rheumatoid factor negative, polyarticular rheumatoid factor positive, and pauciarticular type I. Severe arthritis is associated with polyarticular rheumatoid factor negative, polyarticular rheumatoid factor positive, and systemic onset. Leukemia is the most common childhood cancer followed by brain cancer.[15] The most common childhood posterior fossa cancer is cerebellar astrocytoma followed by medulloblastoma.[15] MRI with contrast is the gold standard diagnostic tool for brain cancer.[15] Headache and weakness are common symptoms, and seizure is a frequent presenting sign for brain cancer.[15] Rehabilitation focus for brain cancer is on deficits in cognition, speech, language, swallow, mobility, ambulation, ADLs, safety, and community reintegration. Specific location of the brain cancer often determines the deficits.[15] Osteosarcoma is the most common childhood primary bone tumor.[15] Amputation or limb salvage is often the treatment.[15] Rehabilitation focus is on amputation, prosthetic and pain management, and community reintegration. The Journal of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine ¦ Volume 2 ¦ Supplement 1 ¦ June 2019 S33 [Downloaded free from http://www.jisprm.org on Thursday, August 20, 2020, IP: 114.108.251.132] Wu and Ahn: PRM clinical scope gerIatrIc condItIons Geriatric rehabilitation focuses on changes in body systems as part of normal and abnormal aging. It is not always clear whether a certain change, for example, development of muscle weakness, is a natural aging process or due to disuse or other comorbidities. Aging with a disability is a related but separate consideration that concerns the decline in the ability to manage and compensate for functional deficits with advancing age. Physiologic changes associated with aging involve multiple body systems. Muscle strength – force produced by single muscle fibers, force per unit cross-sectional area, and the ability to generate force rapidly – declines with age.[16] The elderly experience decreases in exercise-induced adaptations, such as increased heart rate, stroke volume, and cardiac output.[17] Postural hypotension is more common in the aged, leading to increased risk of falls. Thoracic wall mobility and vital capacity decrease and the effort needed to overcome wall stiffness increases in older adults.[16] Loss of bone density is more common in the elderly. Skin frailty prevails consequent to reduced tissue elasticity, decreased blood perfusion, and loss of sensory sensitivity. Visual and auditory acuity also decline with age. Diseases and disorders that are more common in the elderly and negatively impact the function of an aging individual include cerebrovascular accident, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, degenerative joint and spine disease, osteoporosis, motor neuron disease, Parkinson’s disease, malignancy, and dementia. Disuse and immobilization brought on by disability have a greater significance in older than younger adults as evidenced by more pronounced immobilization-induced loss of lean body mass in older persons.[18] Financial support and sponsorship Nil. Conflicts of interest There are no conflicts of interest references 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. suMMary The clinical practice of the medical specialty of PRM includes patients with a wide variety of health conditions that have significant effects on function and quality of life. Although there are exceptions, most health conditions in a PRM setting affect the nervous, musculoskeletal, and/or cardiopulmonary systems, sometimes independently but also in combination. More specifically, patients with brain disorders (stroke and traumatic brain injury) and spinal cord injuries can significantly benefit from PRM interventions. Disorders of single or multiple joints (including the limbs and spine) represent a large percentage of the patient population in a PRM practice; this has been particularly true in the last 10–20 years. In some centers, patients with cardiac dysfunction, pulmonary disease, and cancer are targets of rehabilitation programs. Age is not a criteria for the selection of patients for PRM services, and both children and elderly have conditions amenable and responsive to PRM interventions. S34 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013;127:e6-245. Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP, editors. Cerebrovascular diseases. In: Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014. p. 778-884. Ahmed S, Venigalla H, Mekala HM, Dar S, Hassan M, Ayub S, et al. Traumatic brain injury and neuropsychiatric complications. Indian J Psychol Med 2017;39:114-21. Wagner AK, Arenth PM, Kwasnica C, Rogers EH. Traumatic Brain Injury. In: Braddom RL, Chan L, Harrast MA, Kowalske KJ, Matthews DJ, Ragnarsson KT, Stolp KA, editors. Physical Medicine and Rehabiliation. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. p. 1133-75. Rahimi-Movaghar V, Sayyah MK, Akbari H, Khorramirouz R, Rasouli MR, Moradi-Lakeh M, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in developing countries: A systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 2013;41:65-85. Stanton TR, Leake HB, Chalmers KJ, Moseley GL. Evidence of impaired proprioception in chronic, idiopathic neck pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther 2016;96:876-87. Trompeter K, Fett D, Platen P. Prevalence of back pain in sports: A systematic review of the literature. Sports Med 2017;47:1183-207. Varma P, Stineman MG, Dillingham TR. Epidemiology of limb loss. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2014;25:1-8. Ahmad N, Thomas GN, Gill P, Torella F. The prevalence of major lower limb amputation in the diabetic and non-diabetic population of England 2003-2013. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2016;13:348-53. Østlie K, Skjeldal OH, Garfelt B, Magnus P. Adult acquired major upper limb amputation in norway: Prevalence, demographic features and amputation specific features. A population-based survey. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:1636-49. Data & Statistics for Cerebral Palsy; 2016. Available from: https://www. cdc.gov/ncbddd/cp/data.html. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 10]. Wu SS, Cohen JM, Bodeau VS, Stiens SA. Neural tube defects: Anatomy, associated deficits, and rehabilitation. In: O’Young BJ, Young MA, Stiens SA, editors. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Secrets. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. Huang JL, Yao TC, See LC. Prevalence of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile chronic arthritis in a Chinese population: A nation-wide prospective population-based study in Taiwan. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2004;22:776-80. Manners PJ, Diepeveen DA. Prevalence of juvenile chronic arthritis in a population of 12-year-old children in Urban Australia. Pediatrics 1996;98:84-90. Gonzalez P, Luciano L, Schuman RM. Cancer rehabilitation. In: Cuccurullo SJ, editor. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Board Review. 3rd ed. New York: Demos Medical; 2015. p. 708-27. Hughes VA, Frontera WR, Wood M, Evans WJ, Dallal GE, Roubenoff R, et al. Longitudinal muscle strength changes in older adults: Influence of muscle mass, physical activity, and health. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:B209-17. Bloch RM. Geriatric rehabilitation. In: Braddom RL, Chan L, Harrast MA, Kowalske KJ, Matthews DJ, Ragnarsson KT, Stolp KA, editors. Physical Medicine and Rehabiliation. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. p. 1419-37. Kortebein P, Ferrando A, Lombeida J, Wolfe R, Evans WJ. Effect of 10 days of bed rest on skeletal muscle in healthy older adults. JAMA 2007;297:1772-4. The Journal of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine ¦ Volume 2 ¦ Supplement 1 ¦ June 2019