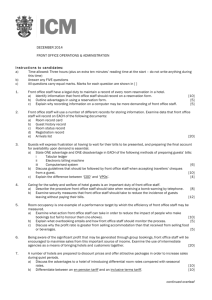

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1754-2731.htm Does guests-perceived value for money affect WOM and eWOM? The impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM Gustavo Quiroga Souki Faculty of Economics, Research Centre of Tourism, Sustainability, and Wellbeing (CinTurs), University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal and TRIE/ISMAT - Lusofona, ISMAT, Portim~ao, Portugal Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM Received 20 March 2023 Revised 24 May 2023 Accepted 5 June 2023 Alessandro Silva de Oliveira Department of Administration, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Chapad~ao do Sul, Brazil lio Correa Barcelos Marco Tu Master`s Program in Administration, Centro Universitario Una, Belo Horizonte, Brazil lio da Costa Mendes Maria Manuela Martins Guerreiro and Ju Faculty of Economics, Research Centre of Tourism, Sustainability, and Wellbeing (CinTurs), University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal, and Luiz Rodrigo Cunha Moura Doctoral and Master`s Program in Administration, Fumec University, Belo Horizonte, Brazil and Master`s Program in Administration, Fundaç~ao Cultural Dr Pedro Leopoldo, Pedro Leopoldo, Brazil Abstract Purpose – Hotels provide high-quality guest experiences to generate perceived value for money (PVM), positively influencing word-of-mouth (WOM) and electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) communication. This study aims to (1) verify the impacts of the perceived quality by the guests about their experiences in hotels on their PVM; (2) inspect the influence of guests’ perception of hotel prices on PVM; (3) examine the impacts of guest PVM on their hotel experiences on WOM and eWOM and (4) investigate the consequences of the hotel guests’ behavioural engagement on social networking sites (HGBE-SNS) on eWOM. Design/methodology/approach – This quantitative and descriptive study consists of a survey with 371 guests who evaluated their experiences at three hotels in Brazil. PLS-SEM tested the hypothetical model that resorted to the stimulus-organism-response theory (S-O-R), proposed by Mehrabian and Russell (1974). Cluster Analysis compared the PVM, WOM and eWOM of groups of hotel guests with different levels of social media engagement. Findings – Perceived quality by hotel guests positively impacts PVM. Perceived price negatively influences PVM. PVM had a positive and robust impact on WOM. PVM impacts and explains weakly eWOM. In contrast, HGBE-SNS affects and better explains eWOM than PVM. Originality/value – This unprecedented investigation concomitantly exhibits the relationships between perceived quality, price, PVM, WOM, eWOM and HGBE-SNS. Hotels must offer high perceived quality experiences to influence PVM and WOM positively. PVM is unable to stimulate eWOM strongly. HGBE-SNS is This paper is financed by National Funds provided by FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology through project UIDB/04020/2020. The TQM Journal © Emerald Publishing Limited 1754-2731 DOI 10.1108/TQM-03-2023-0088 TQM pivotal for guests to share their hotel experiences through eWOM. This study suggests marketing strategies for hospitality companies to amplify customer engagement on SNS. Keywords Hospitality, Consumer behaviour, Tourism, Service quality, Customer services quality, Hotels Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction Organisations in tourism, food service and hospitality which provide high-quality experiences to their customers expect to generate increased perceived value for money (PVM), positively impacting their attitudes and behavioural intentions (Souki et al., 2020; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2016). PVM is pivotal to understanding consumer behaviour and its impacts on companies’ competitiveness and economic sustainability (Permatasari, 2020). In this way, the PVM by consumers about their experiences, their antecedents and consequents have aroused the interest of managers, marketing professionals and academics from the abovementioned economic sectors (Zhang et al., 2022; Caber et al., 2020; Souki et al., 2020; Alnawas and Hemsley-Brown, 2019). Zeithaml (1988) conceptualises PVM as the general assessment of the usefulness of products or services, considering the perception of consumers about what they receive (benefits) and what they give in return (sacrifices). Zhang et al. (2019) state that PVM is a trade-off between benefits and costs that consumers perceive when effectuating transactions. For this reason, several authors have studied the different facets of PVM, its antecedents, and its consequents in hospitality (Zhang et al., 2022; Permatasari, 2020; Alnawas and HemsleyBrown, 2019). Perceived quality stands out among the antecedents of PVM (Alnawas and HemsleyBrown, 2019). It is because perceived quality represents the benefits consumers receive during their consumption experiences (Zeithaml, 1988). Souki et al. (2020) argue that perceived quality is the perception of consumers about the performance of products and/or services in attributes that potentially satisfy their needs and expectations compared to competitors. It is worth mentioning that consumer experiences encompass affective, cognitive, physical and social responses to interactions with service providers (Kim and So, 2022; Zhang et al., 2019). Accordingly, guests’ perceptions about the quality of their hotel experiences affect their attitudes and future behaviours (Shahid and Paul, 2022; Bravo et al., 2019). Hence, providing experiences with high perceived quality standards by guests is critical in hospitality (Kim and So, 2022). Alnawas and Hemsley-Brown (2019) recommend that hotels supervise the perceived quality by guests regarding their experiences and how they influence their attitudes and behaviours to keep them competitive. Price is another essential antecedent for assessing the PVM by guests during their hotel experiences. This construct refers to the monetary value consumers pay to obtain products and services (Iglesias and Guillen, 2004). Therefore, price is the financial value guests spend to enjoy hotel experiences. Previous studies have contemplated the impact of guests’ perceptions of the prices paid for their hotel experiences on the PVM (Pan et al., 2022; Padma and Ahn, 2020; Jeaheng et al., 2020; Alnawas and Hemsley-Brown, 2019). In addition to the antecedents of PVM represented by the perceived quality and perceived price, the present study considers some of its consequents, namely word of mouth communication (WOM) and electronic word of mouth communication (eWOM). Ahmadi et al. (2023) state that WOM and eWOM are paramount for companies, but they are conceptually distinct constructs with different measurement indicators (Lin et al., 2022; Serra-Cantallops et al., 2020). Moreover, studies that cover WOM and eWOM in tourism, food service or hospitality simultaneously are rare (Lin et al., 2022; Confente et al., 2020). Prior research has addressed the direct and positive impacts of PVM by customers during their consumption experiences on WOM (Kuppelwieser et al., 2022), particularly in tourism (Caber et al., 2020) and hospitality (Zhang et al., 2022). Other studies contemplated the effects of PVM on eWOM. However, some studies corroborate this direct and positive relationship (Sampat and Sabat, 2021; Uslu and Karabulut, 2018), and others do not confirm such an association (Rouibah et al., 2021; Samadara and Fanggidae, 2020). Although eWOM is crucial for the hospitality industry, additional research is needed to deepen knowledge of the relationship between PVM and eWOM (Confente et al., 2020). Thus, the first gap in the literature that the present study intends to fill refers to examining the direct and positive effects of the PVM by guests about their hotel experiences on WOM and eWOM concomitantly. Social networking sites (SNS) allow consumers to obtain information, evaluate and comment on their consumption experiences, and share content through eWOM anywhere and at any time (Chen et al., 2022a; Sampat and Sabat, 2021; Park, 2020; Sann et al., 2020). Souki et al. (2022a) argue that consumers are increasingly engaged and proactive in creating and exchanging content on SNS. Wang and Kubickova (2017) corroborate, emphasising that the number of people engaged in SNS increases the impact of eWOM in the hotel industry. However, Correia et al. (2018) and Dolan et al. (2016) highlight that consumers have distinct levels of behavioural engagement in SNS. The investigation conducted by Souki et al. (2022b) reveals that restaurant consumers’ behavioural engagement in SNS moderates the relationship between their memorable experiences and eWOM. In this context, the second gap that this study intends to fill refers to testing whether the construct of hotel guests’ behavioural engagement on social networking sites (HGBE-SNS) directly and positively impacts the eWOM about their experiences. Notably, the present study is unprecedented, as no previous investigation has evaluated the impacts of the HGBE-SNS on eWOM. Considering the above, this study’s guiding questions are: (1) Does the quality guests perceive about their hotel experiences directly and positively impact their PVM? (2) Does guests’ perception of the price of hotel experiences directly and negatively affect their PVM? (3) Does the PVM by guests in their hotel experiences directly and positively impact WOM and eWOM concomitantly? (4) Does the HGBE-SNS directly and positively impact the eWOM about their hotel experiences? The authors used the stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) theory, developed by Mehrabian and Russell (1974), to address this research’s guiding questions. This theory examines the connections between environmental stimulus, emotional and cognitive states and consumer reactions and behaviours. The S-O-R theory argues that physical or social stimuli directly alter people’s emotional and cognitive states (organism), influencing their subsequent responses and behaviours (Leung et al., 2021; Brewer and Sebby, 2021; Dedeoglu et al., 2018). Several authors have resorted to the S-O-R theory in studies on consumer experiences in hospitality (Haobin et al., 2021; Tan, 2023) and food services (Chinelato et al., 2023; Souki et al., 2022b; Leung et al., 2021). However, no previous studies simultaneously describe the relationships between (1) environmental stimuli – perceived quality and perceived price by hotel guests; (2) organism – cognitive (perceived value for money); and; (3) behavioural responses – WOM and eWOM. Additionally, no previous studies testing the impact of HGBESNS on eWOM (response) were identified. In this way, the present investigation craves to fill the abovementioned gaps. Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM TQM This study aims to (1) verify the impacts of the perceived quality by the guests about their experiences in hotels on their PVM; (2) inspect the influence of guests’ perception of hotel prices on PVM; (3) examine the impacts of guest PVM on their hotel experiences on WOM and eWOM and (4) investigate the consequences of the hotel guests’ behavioural engagement on social networking sites (HGBE-SNS) on eWOM. The present study is unprecedented and contributes to the academy because no previous investigation has concomitantly encompassed the relationships between all the constructs contemplated by it (perceived quality, perceived price, PVM, WOM, eWOM and HGBE-SNS), particularly in hospitality. Moreover, this study contributes to academia by using the S-O-R theory to show the direct effects of perceived quality and perceived price by hotel guests (stimulus) on PVM (organism) and subsequent impacts on WOM and WOM (responses). In this sense, this investigation demonstrates that PVM affects WOM and eWOM differently, filling the first gap identified in the literature. It is because the PVM by the guests directly, positively and strongly impacts the WOM. In contrast, the impact of PVM on eWOM is direct and positive but negligible. This study fills the second identified theoretical gap by proving that the HGBE-SNS is an independent construct that directly, positively and strongly impacts the eWOM (response). Furthermore, it reveals that the HGBE-SNS is more relevant than the PVM in explaining the eWOM. As a managerial contribution, the results prove that providing experiences with a high standard of quality perceived by guests and low perceived prices generates a high PVM, positively impacting WOM. However, the HGBE-SNS is more relevant to forging eWOM than the perceived quality and perceived prices. Thus, to achieve positive eWOM, hotel managers must consider the quality of their guests’ experiences and fees charged for accommodation and their level of engagement in SNS. Hence, hotel managers should encourage and monitor the HGBE-SNS to expand the benefits of eWOM for their companies. This study also contributes managerially by providing practical recommendations for marketing strategies focused on customer engagement for hospitality businesses. Finally, although the relationship between perceived quality and PVM is well established in the hospitality literature (Jeaheng et al., 2020; Souki et al., 2020), this study identifies the dimensions of perceived quality that impact most PVM. Some dimensions are tangible (e.g. infrastructure), while others are intangible (e.g. atmosphere, customer orientation, service quality and reputation). Accordingly, it is a relevant managerial contribution of this study, as it suggests strategic priorities for hotel managers. 2. Theoretical background and research hypotheses This study resorted to the S-O-R theory to exhibit the relationships between the hypothetical model’s constructs (Figure 1). The perceived quality by guests about their experiences in hotels (stimulus) is a second-order construct that reflects the following first-order constructs: accessibility and convenience, infrastructure, hotel restaurant, infrastructure and leisure activities, services quality, atmosphere, customer orientation, social endorsement, reputation and status. Such perceived quality dimensions by hotel guests and their measurement items come from previous studies (Souki et al., 2020; Radojevic et al., 2018). This study’s hypothetical model also evaluates the impacts of the perceived quality by guests regarding their experiences in hotels and the perceived price (stimulus) on PVM (organism). Furthermore, this research investigates the effects of PVM (organism) on WOM and eWOM (responses). Finally, the impact of the HGBE-SNS on their eWOM about the hotel experiences is examined. 2.1 Perceived quality and its impact on PVM According to Zeithaml (1988), perceived quality refers to consumers’ subjective perception of the performance of products and/or services in tangible and intangible attributes that can Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM Figure 1. Hypothetical model potentially satisfy their needs, expectations and desires compared to competitors (Souki et al., 2020). PVM, in turn, refers to consumers’ judgements about the usefulness of products and/or services when comparing the benefits received and the sacrifices made to obtain them (Zeithaml, 1988; Monroe, 1979). Zhang et al. (2019) argue that PVM represents a trade-off between the benefits and sacrifices consumers perceive when exchanging goods and/or services. Previous studies demonstrate that perceived quality directly and positively impacts PVM (Garcıa-Fernandez et al., 2018), particularly in food service (Chen et al., 2020; Souki et al., 2020; Thielemann et al., 2018) and in hospitality (Alnawas and Hemsley-Brown, 2019). Hu and Dang-Van (2023) used the S-O-R Theory to evidence that guests’ perception of the indoor environmental quality of five-star green luxury hotels is a stimulus that positively influences consumers’ affectivity and perceived value (organism). Thus, as indicated by the S-O-R Theory, the dimensions of perceived quality were considered in the present study as stimuli capable of influencing the PVM, which was considered an organism (cognitive state). Considering the above, this study’s first hypothesis is: H1. The perceived quality by guests regarding their hotel experiences has a direct and positive impact on PVM. 2.2 Perceived price and its impact on PVM Consumers make monetary and non-monetary sacrifices to obtain products and/or services. Price is the amount consumers pay to purchase products, services, or experiences (Monroe, 1979). Among the non-monetary sacrifices are the mental and physical efforts, time spent and transaction costs (Thielemann et al., 2018; Iglesias and Guillen, 2004). Guest perceptions of hotel prices during their experiences have been studied in previous investigations (Jeaheng et al., 2020; Alnawas and Hemsley-Brown, 2019; Radojevic et al., 2018). Pan et al. (2022) state that several factors can influence guests’ perceptions of hotel prices, making their evaluations subjective. Padma and Ahn (2020) point out that many guests use prices as criteria to assess the quality of services provided by hotels. Alnawas and Hemsley-Brown TQM (2019) argue that guests tend to judge that hotels with high prices offer superior services, while establishments that charge low prices are likely to provide lower-quality services. Accordingly, consumers have a strong orientation related to PVM, comparing their perception of prices with the quality of products, services and experiences (Thielemann et al., 2018). Previous studies indicate that perceived price directly and negatively impacts PVM (Jeaheng et al., 2020; Souki et al., 2020; Thielemann et al., 2018). Tan et al. (2022) studied ethnic restaurants resorting to the S-O-R Theory and discovered that the perceived price is a stimulus that affects the organism (customers’ positive emotions). Thus, in this study, the perceived price is a stimulus that influences the PVM (organism). Hence, the following hypothesis is: H2. The perceived price directly and negatively impacts the PVM by guests regarding their hotel experiences. 2.3 Impacts of PVM on WOM WOM is one of the consumer behavioural responses that arouses the interest of managers, marketing professionals and academics. According to Arndt (1967), WOM refers to the interpersonal communication of information about a product, service or company from one person to another. Thus, WOM is related to informal interpersonal interaction between former customers, current consumers and prospects regarding perceptions and opinions about products, services, brands and experiences (Souki et al., 2020; Park, 2020). Accordingly, consumers share their experiences with others, impacting their attitudes and behaviours. Shahid and Paul (2022) and Bravo et al. (2019) argue that favourable WOM is paramount for hotels, as it positively influences consumers’ purchasing decisions. Several authors have studied the antecedents of WOM in tourism, hospitality and food service. Previous studies reveal that the perceived quality by guests during their tourist destination experiences impacts their WOM (Chen et al., 2022b). Souki et al. (2020) demonstrated that consumer satisfaction in a la carte restaurants positively affects WOM. Choi and Kandampully (2019) and Sukhu et al. (2019) corroborate by pointing out that hotel guest satisfaction positively impacts WOM. Finally, several studies confirm the direct and positive impacts of PVM by consumers during their experiences in WOM (Kuppelwieser et al., 2022), namely in tourism (Caber et al., 2020) and hospitality (Zhang et al., 2022; Moise et al., 2021). Therefore, consonant with the S-O-R Theory, the PVM (organism) influences guests’ WOM about their hotel experiences (response) in the present investigation. Considering the above, the following hypothesis is: H3. PVM by guests about their hotel experiences directly and positively impacts WOM. 2.4 Impacts of PVM on eWOM Although communication between consumers through the Internet has been an object of interest to managers, marketing professionals and academics since the 1990s (Stauss, 1997), its colossal growth in the last few years has expanded the opportunities for interaction between people and institutions globally by eWOM (Souki et al., 2022b). It is because eWOM permits sharing and obtaining information from friends, acquaintances, colleagues and unknown people about products, services, brands and experiences through the Internet (Ratchford et al., 2001). Hennig-Thurau et al. (2004) conceptualise eWOM as any positive or negative statement made by potential, current or former consumers about products, services or companies made available to many people and institutions through the Internet. According to Park (2020), several platforms allow users to communicate through eWOM, such as SNS, discussion forums, shopping sites, blogs and review sites. Souki et al. (2022a) argue that consumers can engage in SNS, generating and sharing content over the Internet due to the rapid evolution of information and communication technologies. Sann et al. (2020) point out that tourism and hospitality were strongly affected by the greater interactivity between organisations and customers provided by the Internet and, more particularly, by SNS (Wang and Kubickova, 2017). It is because customers share their experiences with their contacts by posting texts, photos and videos, among other content, on SNS (Chinelato et al., 2023). Rouibah et al. (2021) state that consumers tend to be more influenced by content generated by their peers than by those produced by companies. Kim et al. (2018) corroborate this, highlighting that many guests consider the content created and made available by other guests more reliable than that published institutionally by hotels. In this sense, eWOM is vital for the hotel industry today, suggesting managers monitor guest feedback about their experiences in the SNS (Confente et al., 2020; Wang and Kubickova, 2017). Previous studies have contemplated the effects of PVM by consumers regarding their eWOM experiences. Bushara et al. (2023) used the S-O-R Theory to demonstrate that the PVM is an organism that mediates social media marketing activities (stimulus) and directly and positively impacts purchase intention and e-WOM (responses) in the restaurant industry context. However, some studies confirm this direct and positive relationship (Bushara et al., 2023; Sampat and Sabat, 2021; Uslu and Karabulut, 2018), and others do not corroborate such an association (Rouibah et al., 2021; Samadara and Fanggidae, 2020). In line with the S-O-R Theory, the PVM is considered as an organism and the eWOM as a response in the present study. Therefore, the following hypothesis is: H4. PVM by guests regarding their hotel experiences directly and positively impacts their eWOM. 2.5 Impacts of HGBE-SNS on eWOM Consumer behavioural engagement on SNS includes behaviours such as following people and organisations on SNS, liking and commenting on posts, sharing content published by others, producing and publishing content (e.g. texts, photos, audio and videos) and indicating products, services, companies or brands to other people (Bailey et al., 2021; Correia et al., 2018; Dessart, 2017). Marketing managers have used the behavioural engagement of consumers in SNS to monitor the performance of companies in SNS (Dessart, 2017). However, consumers have different levels of engagement in SNS, as some are active and others passive (Correia et al., 2018; Dolan et al., 2016). Tussyadiah et al. (2018) argue that understanding consumer engagement in SNS and its repercussions on eWOM is essential for companies, particularly in tourism (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021), food service (Chinelato et al., 2023; Souki et al., 2022b) and hospitality (Wang and Kubickova, 2017). These authors also point out that hotel managers should create strategies and actions to stimulate the HGBE-SNS to amplify the effectiveness of the eWOM. Thus, the following hypothesis is: H5. The HGBE-SNS directly and positively impacts guests’ eWOM about their hotel experiences. 3. Methodology The present study is quantitative and descriptive. A cross-sectional survey was conducted with guests from three hotels in three Brazilian cities. Initially, a literature review identified the quality dimensions that guests perceive and use to assess their hotel experiences. The dimensions of perceived quality are benefits hotels offer to their guests. In contrast, price Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM TQM refers to the monetary amount consumers spend to enjoy these experiences (Souki et al., 2020). Thus, the hypothetical model proposed in this study includes perceived quality factors during their hotel experiences and price, as they constitute stimuli that affect guests’ attitudes and behaviours (Jeaheng et al., 2020; Radojevic et al., 2018). This study’s hypothetical model also includes the PVM (Jeaheng et al., 2020; Alnawas and Hemsley-Brown, 2019), the WOM (Bravo et al., 2019), the eWOM (Chen et al., 2022a; Line et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2022; Sann et al., 2020) and the HGBE-SNS (Correia et al., 2018; Dolan et al., 2016). This study’s constructs are adapted from previous research (Table 1). In addition to the items for measuring perceived quality and price, this investigation’s questionnaire included questions about the guests’ sociodemographic profiles at the investigated hotels. This data collection instrument is constituted by 11-point interval scales, where zero (0) means “totally disagree”, and ten (10) means “totally agree”. Considering that some respondents may not have used part of the services offered by the hotels, the questionnaire also included the option “DK/DA” (do not know/does not apply). This study’s unit of analysis is guests staying in three hotels in three Brazilian cities. Dolma (2010) affirms that the unit of analysis is related to the entity analysed during a scientific investigation. Units of analysis are typically categorised into levels, and in the social sciences, individuals are commonly assumed as levels. This author exemplifies students, employees, citizens, managers and consumers as units of analysis at the individual level. The unit of analysis must consider “who” and “what” the researchers are interested in analysing. This study focused on analysing guests from three Brazilian hotels (“who”) to (1) verify the impacts of the perceived quality by the guests about their experiences in hotels on the PVM by them; (2) inspect the influence of guests’ perception of the price paid for their hotel experiences on their PVM; (3) examine the impacts of guest PVM on their hotel experiences on WOM and eWOM; and (4) investigate the consequences of the HGBE-SNS on the eWOM about their hotel experiences. Hence, such objectives represent “what” the study investigated. This research took place in three hotels in Brazil from 01/04/2020 to 01/19/2020, totalling 15 days of data collection. Hotel guests were informed about this study’s objectives and the voluntary nature of their participation, in addition to the guarantee of preserving the confidentiality of individual information. Guests completed the questionnaires at the hotel facilities seven days a week and at different times to contemplate the opinion of guests with various profiles. The sample consisted of 371 guests staying in three hotels in three Brazilian cities through the non-probabilistic technique for accessibility and convenience (Malhotra et al., 2017). Such authors argue that non-probabilistic samples can provide reasonable estimates of the characteristics of the surveyed universe, although the results cannot be extrapolated. Hair et al. (2017) and Chin and Newsted (1999) recommend checking whether the research sample is adequate and the statistical analysis power used. Accordingly, this study used the G* Power 3.1.9.4 software (Faul et al., 2009). Hair et al. (2017) recommend including the structural model constructs with more predictors, the significance level, statistical power and average effect size to calculate the minimum sample. In this study’s structural model, the constructs with more predictors are PVM (perceived quality and price) and eWOM (PVM and HGBESNS), which were impacted by two constructs each (Figure 1). Assuming these constructs, the significance level of 5%, the statistical power of 0.08 and the average effect size (f2 5 0.15, which means a moderate impact of R2 5 13%), the minimum sample indicated was 95 observations. However, the researchers tested more rigorous criteria, considering a significance level of 1%, a statistical power of 0.01 and a mean effect size of f2 5 0.15. In this case, the recommended minimum sample size was 188 individuals (Cohen, 1988). As the present study covered 371 hotel guests, the final sample included 3.91 times more individuals than the less rigorous criterion recommended and 1.97 times more cases than the most Constructs Measurement items Sources Accessibility and convenience This hotel . . . is well located is easy to get This hotel . . . has a beautiful external appearance has an attractive internal appearance appears to be well organised has a clean and hygienic environment has apartments of different size has spacious and comfortable apartments This hotel’s restaurant . . . has an attractive appearance is well sanitised and clean offers a varied menu with several options for customers offers food of excellent quality has an excellent service This hotel offers . . . swimming pools recreation games room multi-sport courts This hotel . . . offers polite and kind staff to serve guests has employees with the necessary knowledge to answer customers questions has employees always willing to help customers has honest and transparent employees in customer relations has employees with a good appearance (uniform, hygiene) has employees who solve customer needs and desires quickly and effectively has employees who respond to customer requests within the promised time This hotel has . . . a pleasant atmosphere a warm and friendly environment a good relationship between people (managers, employees and customers) nice and nice customers This hotel . . . cares and strives to solve customer problems cares about customer opinion and satisfaction is honest, fair and transparent with customers handles customer complaints in a correct and timely manner Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Infrastructure Hotel’s restaurant Infrastructure and leisure activities Services quality Atmosphere Customer orientation Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) and Radojevic et al. (2018) Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Adapted from Radojevic et al. (2018) Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) (continued ) Table 1. Constructs, measurement items and sources TQM Constructs This hotel . . . is highly valued by my friends and/or family is a place where the people I like to hang out with frequent is a place that my friends and/or family visit regularly is a place that my friends and/or family recommend Reputation This hotel . . . is traditional is quite well known/famous has a good reputation has a recognised brand in the restaurant industry Status This hotel . . . It is frequented by people with a high social status It is frequented by successful people gives its patrons prestige is a trendy restaurant Perceived price This hotel . . . charges high prices for hosting usually has a high bill charges the highest prices among hotels of the same category in its region Perceived value for This hotel . . . money is good value for money offers a quality of services compatible (fair) considering the value it charges its customers charges a fee for its services that is worth paying WOM I say positive things about this hotel to my relatives and friends I share my experiences with this hotel with others I recommend this hotel to others I encourage people to visit this hotel eWOM I talk about this hotel on social networks I share my experiences with this hotel on social networks I give my opinion about this hotel on social networks HGBE-SNS I seek information about hotels on social networks I tag people on social networks when I take pictures in hotels I share content about hotels posted by friends on social networks I often check-in (report where I am) on social networks when I stay in hotels Advertisements of hotels on social networks help me choose where to stay Source(s): Research data Social endorsement Table 1. Measurement items Sources Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Adapted from Souki et al. (2020) Adapted from Choi and Kandampully (2019) and Dedeoglu et al. (2018) Adapted from Serra-Cantallops et al. (2018) and Line et al. (2020) Adapted from Correia et al. (2018) and Dolan et al. (2016) conservative parameter. Finally, the researchers performed the posthoc analysis of the G* Power 3 considering the stricter criteria mentioned above for this study’s final sample, which had 371 cases. The results showed a statistical power of 0.999, confirming that this study’s final sample size is adequate. The researchers tested this research’s hypothetical model through structural equation modelling using partial least squares (PLS-SEM), as recommended by Henseler (2021a) and Hair et al. (2019b). Ali et al. (2018) highlight that the PLS-SEM estimates partial least squares based on regression to explain the variance of the unobserved construct, minimising errors and maximising the R2 values of the endogenous constructs. As suggested by Henseler (2021b), the researchers used the ADANCO 2.3 software to analyse the data this research’s data. This software can examine complex structural models with multiple relationships between variables and simultaneously estimate the research’s structural and measurement models (Henseler, 2021a). Additionally, hotel guests who participated in this study were classified into different groups according to their level of HGBE-SNS through cluster analysis (Hair et al., 2019a; Mooi et al., 2018; H€ardle and Simar, 2015). This analysis allowed identifying the number of guests in each cluster, their sociodemographic profile and the relationship between the level of HGBESNS with other constructs of interest to this study, namely PVM, WOM and eWOM. 4. Analysis and discussion of results 4.1 Sample description The sample included 371 guests from three hotels located in three cities in Brazil. The results show that 55.0% of guests are female and 45.0% are male. Moreover, 40.2% of the participants completed high school, 16.7% were university students and 19.1% completed their undergraduate courses. There was also a higher frequency of guests aged between 18 and 35 (41.5%), followed by those between 36 and 49 (38.0%). Concerning the guests’ marital status, 59.8% are married, while 29.4% are single. 4.2 Estimation of the measurement model Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) estimates the structural model proposed in this study (Hair et al., 2017). Initially, the variables that comprise the constructs were specified. Next, the factor loadings (λ) of the variables that make up each construct were evaluated. Such factor loadings must exceed 0.600 (Hair et al., 2019a). The factor loading with the lowest value in this survey was 0.693. All factor loadings of the variables in this study were significantly lower than 0.001, as revealed by the bootstrapping test. This study’s reliability was also assessed using the Dijkstra-Henseler rho (ρA) and the J€oreskog rho (ρc), as suggested by Henseler (2021a). The ρA and ρc values must be between 0.7 and 0.9 (Sarstedt et al., 2017). In this research, the lowest ρA was 0.823, and ρc was 0.883. Another indicator used to assess the reliability of the constructs was Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (CA), which must be greater than 0.700 for previously tested scales (Hair et al., 2019b). In this study, the minimum CA value was 0.820, demonstrating that all reliability indicators met the parameters suggested by the literature (Table 2). Hair et al. (2019a) suggest investigating whether the indicators of each of the constructs of the hypothetical model have significant relationships with each other through convergent validity. Fornell and Larcker (1981) recommend testing the constructs’ convergent validity using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which indicates the average percentage of shared variance between the latent constructs. Sarstedt et al. (2017) highlight that AVE is demonstrated when its value is more significant than 0.50. All constructs obtained AVE greater than 0.636 in this survey, confirming their convergent validity (Table 2). Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM TQM Constructs Table 2. Convergent validity and reliability 1. Accessibility and convenience 0.823 0.917 0.820 0.847 2. Infrastructure 0.890 0.913 0.885 0.636 3. Hotel’s restaurant 0.929 0.944 0.926 0.773 4. Infrastructure and leisure activities 0.831 0.883 0.824 0.655 5. Services quality 0.932 0.944 0.930 0.706 6. Atmosphere 0.886 0.920 0.883 0.741 7. Customer orientation 0.900 0.929 0.897 0.765 8. Social endorsement 0.894 0.903 0.860 0.700 9. Reputation 0.832 0.885 0.827 0.658 10. Status 0.907 0.928 0.896 0.762 11. Perceived price 0.842 0.898 0.829 0.746 12. Perceived value 0.882 0.927 0.881 0.808 13. CBE-SNS 0.880 0.905 0.868 0.657 14. WOM 0.922 0.943 0.918 0.804 15. eWOM 0.941 0.962 0.941 0.894 Note(s): Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho (ρA); J€oreskog’s rho (ρc); Cronbach’s Alpha (CA); Average Variance Extracted (AVE) Source(s): Research data ρA ρc CA AVE The researchers also investigated the discriminant validity (DV) between the hypothetical model’s constructs using the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of common factor correlations (HTMT). The HTMT criterion is the mean of the correlations of the indicators that measure different constructs concerning the geometric mean of the mean correlations of the items that measure the same construct (Ali et al., 2018). HTMT makes it possible to estimate the true correlation between two constructs (Henseler et al., 2021a). Very high HTMT values reveal problems of discriminant validity between the constructs. Hair et al. (2019b) argue that discriminant validity can be confirmed when HTMT values are less than 0.90 in models with conceptually similar constructs and less than 0.85 in the case of different constructs. This investigation’s results reveal that the HTMT values of the constructs were less than 0.890, which confirms the DV of the model constructs (Table 3). 4.3 Nomological model analysis After evaluating this study’s measurement model, the researchers assessed the structural model using path coefficients (§) and their significance (α). It is worth mentioning that path analysis indicates the cause-and-effect relationships between the model constructs. The bootstrapping technique was also used to provide model estimates, as recommended by Hair et al. (2019a). Figure 2 shows the model path coefficients and their significance. Pearson’s coefficient of determination (R2) evaluates the portion of the variance of endogenous variables explained by exogenous variables that impact them in a structural model (Ringle et al., 2014). Therefore, high R2 values suggest that a structural model’s endogenous constructs (consequent) are well explained by the exogenous constructs (antecedent). Cohen (1988) highlights that the R2 has a negligible effect when it is equal to or less than 2%. The impact is considered medium when the value reaches 13%. The R2 has a strong effect when it obtains values equal to or greater than 26%. Figure 2 presents the R2 values of the model constructs proposed in this study. The perceived quality (§ 5 0.462), along with price (§ 5 0.484) contributes to explaining the PVM (R2 5 64.2%), confirming H1 and H2 respectively. This study proves that PVM directly and positively impacts WOM (§ 5 0.647 and R2 5 41.8%), corroborating H3. 1. Accessibility and convenience 2. Infrastructure 3. Hotel’s restaurant 4. Infrastructure and leisure activities 5. Services quality 6. Atmosphere 7. Customer orientation 8. Social endorsement 9. Reputation 10. Status 11. Perceived price 12. Perceived value 13. CBE-SNS 14. WOM 15. eWOM Source(s): Research data Constructs 1.000 0.731 0.473 0.477 0.546 0.595 0.539 0.470 0.610 0.502 0.277 0.452 0.124 0.639 0.227 1 1.000 0.606 0.649 0.708 0.757 0.702 0.562 0.792 0.595 0.427 0.648 0.109 0.843 0.275 2 1.000 0.529 0.479 0.651 0.558 0.370 0.473 0.446 0.244 0.440 0.218 0.579 0.268 3 1.000 0.499 0.558 0.524 0.433 0.514 0.374 0.446 0.581 0.118 0.627 0.145 4 1.000 0.809 0.843 0.370 0.582 0.410 0.397 0.655 0.119 0.688 0.234 5 1.000 0.890 0.420 0.642 0.467 0.401 0.643 0.129 0.761 0.248 6 1.000 0.408 0.627 0.491 0.432 0.639 0.193 0.713 0.279 7 1.000 0.510 0.597 0.379 0.409 0.206 0.477 0.259 8 1.000 0.450 0.366 0.591 0.213 0.713 0.285 9 1.000 0.329 0.419 0.319 0.542 0.358 10 1.000 0.797 0.168 0.448 0.169 11 1.000 0.200 0.717 0.215 12 1.000 0.223 0.792 13 1.000 0.352 14 1.000 15 Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM Table 3. Discriminant validity: heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) TQM Figure 2. Structural model Hence, these results confirm previous studies that demonstrated this relationship (Kuppelwieser et al., 2022; Caber et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022). On the other hand, the results reveal that the PVM has a low impact on the eWOM (§ 5 0.197), explaining little about this construct’s variation (R2 5 3.9%), as Cohen (1988) suggests. Therefore, this relationship is significant at the 0.001 level, but the results weakly support H4. It is worth mentioning that such values were obtained in the absence of the HGBE-SNS construct in the structural model. However, when adding it to the model, it was observed that the HGBE-SNS directly, positively and strongly impacts the eWOM (§ 5 0.708), which, associated with the reduced contribution of PVM (§ 5 0.078), powerfully explains eWOM (R2 5 52.5%), supporting H5. This result suggests a possible reason why previous studies present inconsistent results regarding the relationship between PVM and eWOM. As previously mentioned, some studies have found direct and positive impacts of PVM on eWOM (Sampat and Sabat, 2021; Uslu and Karabulut, 2018), while others do not corroborate this association (Rouibah et al., 2021; Samadara and Fanggidae, 2020). The present research revealed that the relationship between these constructs is positive but weak, and the HGBE-SNS contributes more than the PVM to explain the eWOM. Thus, this research supports hypotheses H1-H5, although the results for H4 are not very expressive. The researchers conducted a cluster analysis of this survey’s respondents according to their HGBE-SNS to understand the relationships with other constructs of interest, namely PVM, WOM and eWOM. The following section describes the cluster analysis performed and its results. 4.4 Cluster analysis According to Hair et al. (2019a), Mooi et al. (2018) and H€ardle and Simar (2015), cluster analysis allows identifying objects or similar cases based on predetermined variables. Hence, researchers can constitute clusters with individuals analogous to each other (minimum internal variance) but different between groups (maximum external variation) based on significant and heterogeneous samples. In this study, cluster analysis used Ward’s hierarchical method to classify participants according to their HGBE-SNS. Notably, the similarity between groups of hotel guests was estimated according to the average distance between cases. Thus, subjects with smaller intervals were considered similar, and those with greater distances were classified into distinct clusters (Mooi et al., 2018; H€ardle and Simar, 2015). Cluster analysis found solutions with two, three and four clusters considering different levels of HGBE-SNS. The next step was elucidating the most appropriate solution for this study’s objectives. Mooi et al. (2018) and Kotler and Keller (2015) recommend several criteria for choosing the ideal number of clusters. Those authors state that one should analyse the dendrogram created during the cluster analysis, which is a diagram that illustrates the hierarchical relationship between cases or objects. The dendrogram allows the researchers to discover the most suitable alternative for grouping objects into clusters. Another recommended criterion is that the clusters must be sufficiently different from each other (differentiable). In addition, clusters must be identifiable through observable variables, such as a sociodemographic or geographic profile (identifiable). These authors also highlight that groups must be reachable (accessible) and likely to be served by organisations (actionable). Another criterion listed is that the clusters must be long-term stable (reliable). Finally, groups must be relevant. In other words, organisations must be able to meet consumer demands. Considering the criteria above, the researchers evaluated the grouping options with two, three and four clusters. Initially, the dendrogram analysis suggested that the solution with three clusters is the best option for this study’s data. The four clusters’ solution violated the criteria that the groups are few (parsimonious) and differentiable. The alternatives with two and four clusters did not show the sociodemographic differences between them, transgressing the criterion of identification of its members through tangible variables (identifiable profile). The solution with three clusters proved the most appropriate for the present study. Cluster A is composed of 84 individuals (22.6%), Cluster B of 46 respondents (12.4%) and Cluster C of 241 hotel guests (65.0%), comprising the 371 participants of this survey. Besides, the solution with three clusters revealed that Cluster A members had an average age statistically higher than the other clusters (45.9 years). In contrast, the hotel guests of Cluster B had an average age of 35.3 years, and the members from Cluster C had a mean age of 38.3 years. This result demonstrates statistically significant differences between the clusters regarding age, meeting the identifiable profile criterion. However, gender, family income and education variables did not differentiate the groups. The HGBE-SNS means varied significantly between the groups created by the cluster analysis. The results reveal that Cluster A - Low HGBE-SNS had an average of 1.45 on an 11-point scale, where zero (0) represents “totally disagree”, and 10 means “totally agree”. Cluster B - Moderate HGBE-SNS had an average of 3.98, and Cluster C - High HGBE-SNS reached an average of 7.42 (Table 4). Table 4 shows that PVM and WOM do not differ statistically between the three clusters. Thus, a high-value perception is not enough for hotel guests to communicate through eWOM, Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM TQM as all groups have equivalent PVM, but eWOM differs substantially among them. This table also shows that the guests that compound Cluster C - High HGBE-SNS communicate more through eWOM (X 5 7.03AB) than those that comprise the other clusters. Therefore, these findings confirm the results of the structural model that indicate that the high HGBE-SNS is what effectively justifies the eWOM. This investigation supports prior studies demonstrating that hotel guests with low behavioural engagement on SNS have a passive posture, not looking for information or sharing experiences with others but only observing content posted on the SNS (Bailey et al., 2021; Correia et al., 2018). This result reveals that guests with low engagement on SNS tend not to communicate via eWOM, even if they perceive high value in their hotel experiences. On the other hand, guests with high HGBE-SNS seek information, report their experiences and actively participate in communications through SNS (Correia et al., 2018). Finally, guests with a high perception of value in their hotel experiences and a high HGBE-SNS create and publish content on SNS through eWOM. 5. Conclusions and academic and managerial contributions 5.1 Conclusions and academic contributions This study uses the S-O-R theory and contributes to the academy by filling relevant gaps identified in the literature. The first theoretical gap that this study fills is to demonstrate the direct and positive effects of PVM by hotel guests concerning their experiences (organism) on WOM and eWOM (responses). However, the PVM explains the WOM much more (R2 5 41.8%) than the eWOM (R2 5 3.9%). This result suggests that researchers must identify and incorporate other constructs in their theoretical models to explain hotel guests’ eWOM behaviour. Furthermore, this survey reveals offering high-quality experiences that directly and positively impact the PVM by guests contributes significantly to eliciting WOM but is not enough to stimulate eWOM. This investigation also fills the second gap identified in the literature, testing whether the HGBE-SNS directly and positively impacts the eWOM about their experiences. The results show that the HGBE-SNS can better explain the eWOM than the PVM, because the structural model including PVM but without the HGBE-SNS explains the eWOM less (R2 5 3.9%) than the model that incorporates the HGBE-SNS (R2 5 52.5%). Hence, this is the second theoretical contribution of the present study. Finally, no prior studies in hospitality used the S-O-R theory to concomitantly describe the relationships between all the constructs contemplated in this investigation (perceived quality, perceived price, PVM, WOM, eWOM and HGBE-SNS). Therefore, the present work is more comprehensive than previous research, constituting an academic contribution. Moreover, this Cluster A -low HGBESNS Table 4. Comparison between clusters by HGBESNS level Cluster B -moderate HGBESNS Cluster C -high HGBESNS 7.42AB HGBE-SNS 1.45 3.98A Perceived value for 8.08 8.38 8.16 money WOM 7.98 8.30 8.32 eWOM 2.63 3.31 7.03AB Note(s): Results are based on two-sided tests that assume equal variances. For each significant pair, the minor category key appears in the category with the most significant mean The significance level for capital letters A and B: p < 0.05 Using Bonferroni’s correction, the tests are adjusted for all pairwise comparisons in a row of each subtable Source(s): Research data survey proves the quality guests perceive about their hotel experiences (stimulus) directly and positively impacts PVM (organism). In addition, the price perceived by guests (stimulus) to enjoy the benefits offered and the hotel’s experiences directly and negatively impacts the PVM (organism). This finding corroborates previous research (Jeaheng et al., 2020; Souki et al., 2020). However, the cited studies did not use the S-O-R theory. Permatasari (2020) argues that identifying the antecedents of PVM (perceived quality and perceived price) is crucial to understanding consumer behaviour and its impacts on companies’ competitiveness and economic sustainability. 5.2 Conclusions and managerial contributions This study’s first managerial contribution is to indicate which dimensions of perceived quality hotel managers should prioritise to aggregate more PVM by guests. Some of the main dimensions of perceived quality by hotel guests regarding their experiences are tangible (e.g. infrastructure). In contrast, others are intangible (e.g. atmosphere, customer orientation, service quality and reputation). Additionally, managers should associate the quality dimensions guests perceive during their experiences with their pricing strategies to generate high PVM, positively impacting their attitudes and behaviours, such as WOM (Souki et al., 2020) and propensity to loyalty (Thielemann et al., 2018). This study also contributes managerially, demonstrating that hotel managers should not use research results that exclusively consider the WOM construct to make decisions related to eWOM and vice versa. It is worth mentioning that such constructs are conceptually different; they have specific measurement items, and they react differently to stimuli from antecedent constructs. In this way, the conclusions obtained in studies that contemplate only one of these constructs may not be faithfully applied to the other, leading to possible managerial errors. Therefore, the results of the present study suggest that future research simultaneously considers the WOM and eWOM constructs to provide more comprehensive and accurate information for hotel managers. This study reveals that high HGBE-SNS is a pivotal condition for eWOM. Therefore, this is an essential managerial contribution because it proves that managers must encourage and monitor the HGBE-SNS and offer high-quality experiences that generate superior PVM to benefit from more potent and favourable online communication. In this sense and based on this study’s findings, some digital marketing strategies are suggested to increase hotel guests’ engagement in SNS. This survey shows that guests with high HGBE-SNS seek information about hotels on social networks. Thus, it suggests that establishments create valuable, relevant, engaging content for their target audience. Guests with high HGBE-SNS tag others on social media when taking hotel photos. Hence, hotels should offer scenarios, locations, food and drinks, among other visually attractive and differentiated elements, to generate interest, engagement and sharing on social networks. This study also shows that highly engaged guests on SNS share hotel content posted by their friends on social media. In this way, it is advisable to encourage guests to share their hotel experiences through stories, photos and videos and invite their contacts to interact with their posts. This survey reveals that customers with a high HGBE-SNS tend to check in on social networks when staying in hotels. Thus, managers should adopt systems that permit linking Internet access in hotels to the optional sharing of their guests’ check-in on the SNS. This study found that highly engaged guests on SNS use hotel ads on social media to choosing where to stay. Hence, it is recommended that hotels create high-quality fan pages on platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and LinkedIn. Hotels should also offer exclusive promotions to their followers on social networks, keeping them engaged. Finally, managers should monitor the hotel’s fan page to ensure they respond to all guest comments and messages. Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM TQM 6. Research limitations and suggestions for future research This research has some limitations. The first limitation is that the unit of analysis was the guests of three hotels in only one country (Brazil). However, Malhotra et al. (2017) argue that cultural, social, economic and technological aspects influence consumer behaviour. Thus, this investigation’s findings cannot be generalised to hotel guests in other contexts, as they may have different profiles, attitudes and behaviours. Therefore, it is recommended to replicate this investigation in other audiences to obtain external validation for this study’s model. Among the audiences that may be investigated, guests from hotels in other countries or from different categories (e.g. luxury hotels, chain hotels, boutique hotels and farm hotels) stand out. It is suggested that future studies include a guest segmentation variable according to their nationality. The second limitation is that this study’s sample was obtained using the non-probabilistic technique for accessibility and convenience. It is suggested that future research use probabilistic samples. This investigation’s third limitation is that hotel guests completed the questionnaires at a specific time (single cross-sectional study). Future studies may adopt longitudinal or multiple cross-sectional designs to provide more information about the evolution of guests’ behaviour over time. Finally, this study only tested the simultaneous impacts of PVM on WOM and eWOM in the hospitality industry. Future studies may focus on the relationships between these constructs in other economic sectors related to services and, more specifically, tourism, hospitality and leisure (e.g. tourist destinations, food service and entertainment activities). References Ahmadi, A., Taghipour, A., Fetscherin, M. and Ieamsom, S. (2023), “Analyzing the influence of celebrities’ emotional and rational brand posts”, Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 117-136, doi: 10.1108/SJME-12-2021-0238. Ali, F., Rasoolimanesh, S.M., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M. and Ryu, K. (2018), “An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 514-538, doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0568. Alnawas, I. and Hemsley-Brown, J. (2019), “Examining the key dimensions of customer experience quality in the hotel industry”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, Vol. 28 No. 7, pp. 833-861, doi: 10.1080/19368623.2019.1568339. Arndt, J. (1967), “Role of product-related conversations in the diffusion of a new product”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 291-295. Bailey, A.A., Bonifield, C.M. and Elhai, J.D. (2021), “Modeling consumer engagement on social networking sites: roles of attitudinal and motivational factors”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 59, 102348, doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102348. Bravo, R., Martinez, E. and Pina, J.M. (2019), “Effects of service experience on customer responses to a hotel chain”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 389-405, doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2017-0569. Brewer, P. and Sebby, A.G. (2021), “The effect of online restaurant menus on consumers’ purchase intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 94, 102777, doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102777. Bushara, M.A., Abdou, A.H., Hassan, T.H., Sobaih, A.E.E., Albohnayh, A.S.M., Alshammari, W.G., Aldoreeb, M., Elsaed, A.A. and Elsaied, M.A. (2023), “Power of social media marketing: how perceived value mediates the impact on restaurant followers’ purchase intention, willingness to pay a premium price, and E-WoM?”, Sustainability, Vol. 15 No. 6, p. 5331, doi: 10.3390/ su15065331. Caber, M., Albayrak, T. and Crawford, D. (2020), “Perceived value and its impact on travel outcomes in youth tourism”, Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, Vol. 31, 100327, doi: 10.1016/j. jort.2020.100327. Chen, Q., Huang, R. and Hou, B. (2020), “Perceived authenticity of traditional branded restaurants (China): impacts on perceived quality, perceived value, and behavioural intentions”, Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 23 No. 23, pp. 2950-2971, doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020. 1776687. Chen, Y.F., Law, R. and Yan, K.K. (2022a), “Negative eWOM management: how do hotels turn challenges into opportunities?”, Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 692-715, doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2021.1911729. Chen, G., So, K.K.F., Hu, X. and Poomchaisuwan, M. (2022b), “Travel for affection: a stimulusorganism-response model of honeymoon tourism experiences”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, Vol. 46 No. 6, pp. 1187-1219, doi: 10.1177/10963480211011720. Chin, W.W. and Newsted, P.R. (1999), “Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares”, Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 307-341. Chinelato, F.B., Oliveira, A.S.D. and Souki, G.Q. (2023), “Do satisfied customers recommend restaurants? The moderating effect of engagement on social networks on the relationship between satisfaction and eWOM”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. aheadof-print No. ahead-of-print, doi: 10.1108/APJML-02-2022-0153. Choi, H. and Kandampully, J. (2019), “The effect of atmosphere on customer engagement in upscale hotels: an application of SOR paradigm”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 77, pp. 40-50, doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.012. Cohen, J. (1988), Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed., Psychology Press, New York. Confente, I., Vigolo, V. and Brunetti, F. (2020), “The role of WOM in affecting the intention to purchase online: a comparison among traditional vs Electronic WOM in the tourism industry”, in Kaufmann, H.R. and Loureiro, S.M.C. (Eds), Exploring the Power of Electronic Word-Of-Mouth in the Services Industry, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 317-333. Correia, A.C.S., Souki, G.Q. and Moura, L.C.R. (2018), “Facebook user consumption behavior”, Revista Sodebras, Vol. 13 No. 156, pp. 13-24, doi: 10.29367/issn.1809-3957.2018.156. Dedeoglu, B.B., Bilgihan, A., Ye, B.H., Buonincontri, P. and Okumus, F. (2018), “The impact of servicescape on hedonic value and behavioral intentions: the importance of previous experience”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 72, pp. 10-20, doi: 10.1016/ j.ijhm.2017.12.007. Dessart, L. (2017), “Social media engagement: a model of antecedents and relational outcomes”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 33 Nos 5-6, pp. 375-399, doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2017. 1302975. Dolan, R., Conduit, J., Fahy, J. and Goodman, S. (2016), “Social media engagement behaviour: a uses and gratifications perspective”, Journal of Strategic Marketing, Vol. 24 Nos 3-4, pp. 261-277, doi: 10.1080/0965254X.2015.1095222. Dolma, S. (2010), “The central role of the unit of analysis concept in research design”, I_ stanbul € Universitesi I_ şletme Fak€ ultesi Dergisi, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 169-174. Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. and Lang, A.G. (2009), “Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses”, Behavior Research Methods, Vol. 41 No. 4, pp. 1149-1160, doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50, doi: 10.2307/3151312. Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM TQM Garcıa-Fernandez, J., Galvez-Ruız, P., Fernandez-Gavira, J., Velez-Colon, L., Pitts, B. and Bernal-Garcıa, A. (2018), “The effects of service convenience and perceived quality on perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty in low-cost fitness centers”, Sport Management Review, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 250-262. H€ardle, W. and Simar, L. (2015), Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis, 4th ed., Springer, Berlin. Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C. and Sarstedt, M. (2017), A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed., Sage Publications, Los Angeles, p. 350. Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. and Anderson, R.E. (2019a), Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed., Cengage Learning EMEA, Hampshire, p. 813. Hair, J.F., Risher, J.J., Sarstedt, M. and Ringle, C. (2019b), “When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM”, European Business Review, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 2-24, doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203. Haobin, Y.B., Huiyue, Y., Peng, L. and Fong, L.H.N. (2021), “The impact of hotel servicescape on customer mindfulness and brand experience: the moderating role of length of stay”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, Vol. 30 No. 5, pp. 592-610, doi: 10.1080/19368623.2021. 1870186. Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K.P., Walsh, G. and Gremler, D.D. (2004), “Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: what motivates guests to articulate themselves on the internet?”, Journal of Interactive Marketing, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 38-52, doi: 10.1002/dir.10073. Henseler, J. (2021a), Composite-based Structural Equation Modeling: Analysing Latent and Emergent Variables, Guilford Press, New York, NY. Henseler, J. (2021b), ADANCO 2.3, Composite Modeling, Kleve. Hu, X. and Dang-Van, T. (2023), “Emotional and behavioral responses of consumers toward the indoor environmental quality of green luxury hotels”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Vol. 55, pp. 248-258, doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.04.009. Iglesias, M.P. and Guillen, M.J.Y. (2004), “Perceived quality and price: their impact on the satisfaction of restaurant customers”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 16 No. 6, pp. 373-379, doi: 10.1108/09596110410550824. Jeaheng, Y., Al-Ansi, A. and Han, H. (2020), “Impacts of Halal-friendly services, facilities, and food and Beverages on Muslim travellers’ perceptions of service quality attributes, perceived price, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, Vol. 29 No. 7, pp. 787-811, doi: 10.1080/19368623.2020.1715317. Kim, H. and So, K.K.F. (2022), “Two decades of customer experience research in hospitality and tourism: a bibliometric analysis and thematic content analysis”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 100, 103082, doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103082. Kim, S., Kandampully, J. and Bilgihan, A. (2018), “The influence of eWOM communications: an application of online social network framework”, Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 80, pp. 243-254, doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.015. Kotler, P. and Keller, K.L. (2015), Marketing Management, 15th ed., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NY. Kuppelwieser, V.G., Klaus, P., Manthiou, A. and Hollebeek, L.D. (2022), “The role of customer experience in the perceived value–word-of-mouth relationship”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 36 No. 3, pp. 364-378, doi: 10.1108/JSM-11-2020-0447. Leung, X.Y., Torres, B. and Fan, A. (2021), “Do kiosks outperform cashiers? An SOR framework of restaurant ordering experiences”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 580-592, doi: 10.1108/JHTT-03-2020-0065. Lin, P.M., Ok, C.M. and Au, W.C.W. (2022), “Dining in the sharing economy: a comparison of private social dining and restaurants”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 34 No. 1, pp. 1-22, doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-12-2020-1453. Line, N.D., Hanks, L. and Dogru, T. (2020), “A reconsideration of the eWOM construct in restaurant research: what are we really measuring?”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 32 No. 11, pp. 3479-3500, doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2020-0561. Malhotra, N.K., Nunan, D. and Birks, D.F. (2017), Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 5th ed., Pearson Education, Harlow. Mehrabian, A. and Russell, J.A. (1974), An Approach to Environmental Psychology, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Moise, M.S., Gil-Saura, I. and Ruiz-Molina, M.E. (2021), “‘Green’ practices as antecedents of functional value, guest satisfaction and loyalty”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, Vol. 4 No. 5, pp. 722-738. Monroe, K.B. (1979), Pricing: Making Profitable Decisions, McGraw-Hill, New York. Mooi, E., Sarstedt, M. and Mooi-Reci, I. (2018), Market Research: The Process, Data, and Methods Using Stata, 1st ed., Springer, Singapore. Padma, P. and Ahn, J. (2020), “Guest satisfaction and dissatisfaction in luxury hotels: an application of big data”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 84, 102318, doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm. 2019.102318. Pan, H., Liu, Z. and Ha, H.-Y. (2022), “Perceived price and trustworthiness of online reviews: different levels of promotion and customer type”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 34 No. 10, pp. 3834-3854, doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-12-2021-1524. Park, T. (2020), “How information acceptance model predicts customer loyalty? A study from perspective of eWOM information”, The Bottom Line, Vol. 33 No. 1, pp. 60-73, doi: 10.1108/BL10-2019-0116. Permatasari, A. (2020), “The influence of perceived value towards customer satisfaction in hostel business: a case of young adult tourist in Indonesia”, International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management in the Digital Age (IJTHMDA), Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 11-22, doi: 10.4018/ IJTHMDA.2020070102. Radojevic, T., Stanisic, N., Stanic, N. and Davidson, R. (2018), “The effects of traveling for business on customer satisfaction with hotel services”, Tourism Management, Vol. 67, pp. 326-341, doi: 10. 1016/j.tourman.2018.02.007. Rasoolimanesh, S.M., Dahalan, N. and Jaafar, M. (2016), “Tourists’ perceived value and satisfaction in a community-based homestay in the lenggong valley world heritage site”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Vol. 26, pp. 72-81, doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.01.005. Rasoolimanesh, S.M., Seyfi, S., Hall, C.M. and Hatamifar, P. (2021), “Understanding memorable tourism experiences and behavioural intentions of heritage tourists”, Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, Vol. 21, 100621, doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100621. Ratchford, B.T., Talukdar, D. and Lee, M.S. (2001), “A model of consumer choice of the Internet as an information source”, International Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 7-21. Ringle, C.M., Silva, D. and Bido, D.S. (2014), “Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS”, REMark, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 56-73, doi: 10.5585/remark.v13i2.2717. Rouibah, K., Al-Qirim, N., Hwang, Y. and Pouri, S.G. (2021), “The determinants of eWoM in social commerce: the role of perceived value, perceived enjoyment, trust, risks, and satisfaction”, Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM), Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 75-102, doi: 10.4018/JGIM. 2021050104. Samadara, P.D. and Fanggidae, J.P. (2020), “The role of perceived value and gratitude on positive electronic word of mouth intention in the context of free online content”, International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, Vol. 11 No. 10, pp. 391-405. Sampat, B.H. and Sabat, K.C. (2021), “What leads consumers to spread eWOM for Food Ordering Apps?”, Journal of International Technology and Information Management, Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 50-77, available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/jitim/vol29/iss4/3 Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM TQM Sann, R., Lai, P.C. and Chen, C.T. (2020), “Review papers on eWOM: prospects for hospitality industry”, Anatolia, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 177-206, doi: 10.1080/13032917.2020.1813183. Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M. and Hair, J.F. (2017), “Partial least squares structural equation modeling”, Handbook of Market Research, Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 1-40, doi: 10.1007/978-3-31905542-8_15-2. Serra-Cantallops, A., Ramon Cardona, J. and Salvi, F. (2020), “Antecedents of positive eWOM in hotels. Exploring the relative role of satisfaction, quality and positive emotional experiences”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 32 No. 11, pp. 3457-3477, doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-02-2020-0113. Serra-Cantallops, A., Ramon-Cardona, J. and Salvi, F. (2018), “The impact of positive emotional experiences on eWOM generation and loyalty”, Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 142-162, doi: 10.1108/SJME-03-2018-0009. Shahid, S. and Paul, J. (2022), “Examining guests’ experience in luxury hotels: evidence from an emerging market”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 38 Nos 13-14, pp. 1278-1306, doi: 10. 1080/0267257X.2022.2085768. Souki, G.Q., Antonialli, L.M., Barbosa, A.A.S. and Oliveira, A.S. (2020), “Impacts of the perceived quality by guests’ of a la carte restaurants on their attitudes and behavioural intentions”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 301-321, doi: 10.1108/APJML-112018-0491. Souki, G.Q., Chinelato, F.B. and Gonçalves Filho, C. (2022a), “Sharing is entertaining: the impact of consumer values on video sharing and brand equity”, Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 118-136, doi: 10.1108/JRIM-03-2020-0057. Souki, G.Q., Oliveira, A.S.d., Guerreiro, M.M.M., Mendes, J.d.C. and Moura, L.R.C. (2022b), “Do memorable restaurant experiences affect eWOM? The moderating effect of consumers’ behavioural engagement on social networking sites”, The TQM Journal, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print, doi: 10.1108/TQM-06-2022-0200. Stauss, B. (1997), “Global word of mouth: service bashing on the Internet is a thorny issue”, Marketing Management, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 28-30. Sukhu, A., Choi, H., Bujisic, M. and Bilgihan, A. (2019), “Satisfaction and positive emotions: a comparison of the influence of hotel guests’ beliefs and attitudes on their satisfaction and emotions”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 77, pp. 51-63, doi: 10.1016/j. ijhm.2018.06.013. Tan, L.L. (2023), “A stimulus-organism-response perspective to examine green hotel patronage intention”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 35 No. 6, pp. 1552-1568, doi: 10. 1108/APJML-03-2022-0176. Tan, K.H., Goh, Y.N. and Lim, C.N. (2022), “Linking customer positive emotions and revisit intention in the ethnic restaurant: a Stimulus Integrative Model”, Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, Vol. 23, pp. 1-30, doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2022.2156430. Thielemann, V.M., Ottenbacher, M.C. and Harrington, R.J. (2018), “Antecedents and consequences of perceived customer value in the restaurant industry: a preliminary test of a holistic model”, International Hospitality Review, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 26-45, doi: 10.1108/IHR-06-2018-0002. Tussyadiah, S.P., Kausar, D.R. and Soesilo, P.K. (2018), “The effect of engagement in online social network on susceptibility to influence”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, Vol. 42 No. 2, pp. 201-223, doi: 10.1177/1096348015584441. Uslu, A. and Karabulut, A.N. (2018), “Touristic destinations’ perceived risk and perceived value as indicators of e-WOM and revisit intentions”, International Journal of Contemporary Economics and Administrative Sciences, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 37-63. Wang, C.(R.). and Kubickova, M. (2017), “The impact of engaged users on eWOM of hotel Facebook page”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 190-204, doi: 10.1108/ JHTT-09-2016-0056. Zeithaml, V.A. (1988), “Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence”, The Journal of Marketing, Vol. 52 No. 3, pp. 2-22, doi: 10.2307/1251446. Zhang, M., Kim, P.B. and Goodsir, W. (2019), “Effects of service experience attributes on customer attitudes and behaviours: the case of New Zealand cafe industry”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 28-50, doi: 10.1080/19368623.2018.1493711. Zhang, T., Li, B., Huang, A. and Hua, N. (2022), “Examining a perceived value model of servicescape for bed-and-breakfasts”, Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, Vol. 24 No. 4, pp. 359-379, doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2022.2051219. Corresponding author Gustavo Quiroga Souki can be contacted at: gustavo@souki.net.br For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com Impact of consumer engagement on SNS on eWOM