ACCT 2101 Principles of Accounting Final Study Guide

By buying this studying guide, you have made a BIG important step towards acing this final.

You got this, don’t worry! Here are the most important topics from THIS WHOLE

SEMESTER, color coded and with many examples. If you have any questions, you can

always DM me through GroupMe, or you can text me at (720) 202 7262 and I will reply

ASAP. Please enjoy, and best of luck :) - Jimena Castillo

REMEMBER, YOU CAN USE CTRL + F TO SEARCH FOR ANY IMPORTANT VOCAB

YOU ARE TRYING TO FIND. (C ⌘+ F to do this on a Mac)

!!!!! = Suggested to do practice questions involving this objective because it is likely to

appear numerous times on the exam.

This study guide covers the whole semester, so you might guess it will feel lengthy.

Some of the questions given really require some conceptual understanding, rather than

simple math equations. Maybe you need thorough explanations, maybe you don’t. To make

sure you are using your time efficiently, I have put some signs through these pages:

Why Do We Need This?: This sign means I am trying to explain one of the most difficult

concepts that I find hard to understand with merely just numbers. Therefore, I will instead

focus on explaining the WHY and the HOW.

End of Explanation: I have finished explaining, and everything that comes next are essential

vocabulary and practice problems.

Let’s get to work!

CHP 1&2

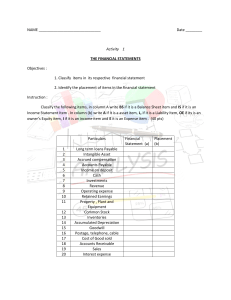

1. Calculate components of the income statement, retained earnings statement,

and balance sheet

Color coded terms show how all statements are connected

Income Statement

For the Period Ending December 31, 2018

Revenues

- Expenses

--------------Net Income/Loss

Retained Earnings Statement

For the Period Ending December 31, 2018

Retained/Earnings, beginning of the period

+ Net Income/Loss

--------------------Total

- Dividends

--------------------Retained Earnings, end of the period

Balance Sheet

As of December 31, 2018

Assets (debits)

+ Liabilities (credits)

+ Stockholders Equity (Including:)

Common Stock

Retained Earnings, end of the period

------------------------------------------------------------------Total Liabilities + S/E = Total Assets

2.

Use the accounting equation to solve for an unknown.

Assets = Liabilities + Stockholders Equity

Example 1: If Assets total $1,000 and Liabilities total $350, how much is

Stockholders Equity?

Assets = Liabilities + Stockholders Equity

$1,000 = $350 + Stockholders Equity

$650 = Stockholders Equity

Example 2: Liabilities increased by $540 and Stockholders decreased by $1,200. By how

much did Assets change? Is it a positive or negative change?

Assets = Liabilities + Stockholders Equity

Assets = + $540 - $1,200

Assets = - $660

Assets decreased by $660.

3. Identify the sections of a classified balance sheet

ASSETS

-

-

-

Current Assets

- Cash and cash equivalents, Short Term Investments, A/R, Inventory, Prepaid

Expenses,

Long Term Assets

- Stock Investments, Investments in Real Estate

Property Plant and Equipment

- Land, Equipment, Buildings

- (SUBTRACT) Accumulated Depreciation

Intangible Assets

- Amortizable Assets

- Franchise and Copyrights

- (SUBTRACT) Accumulated Amortization

- Non Amortizable Assets

- FCC Licenses, Trademarks

- Other Indefinite Lived Intangible Assets

+ Goodwill

LIABILITIES

-

-

Current Liabilities

- Accounts Payable, Accrued Liabilities, Accrued Income Taxes Payable,

Accrued Compensation Payable

Long Term Liabilities

- Long Term debt

STOCKHOLDERS EQUITY

-

Common Stock, Retained Earnings

(SUBTRACT) Dividends

CHP3

1. Analyze the effect of business transactions on the accounting equation.

Business Transactions

Are required when there is a change to Financial Statement accounts.

Have a DUAL-SIDE EFFECT to the Accounting equation.

Must always result in the balanced equation A = L + S/E.

Example #1:

Staples Company bought inventory of 1,000,000 pens for a price total of $1,345,600 on June

23. How does this affect Staples’ transactions?

Staples has acquired some assets (the pens), increasing/debiting its Inventory

account. However, Staples has also spent some cash, so we need to deduce/credit

its Cash account.

June 23

Inventory

Cash

$1,345,600

$1,345,600

Example #2:

Colonial Candle Company pays $1,000,000 of cash dividends to its shareholders on April

16. How does this affect Colonial Candle’s transactions?

The two effects have been: a payment given to dividends and a deduction in cash.

Therefore, we would debit Dividends (Dividends has a normal debit balance) to

increase its amount, and credit Cash to deduct the same amount.

April 16

Dividends

Cash

$1,000,000

$1,000,000

Example #3:

Starbucks Company borrowed $430,100 from the bank on account on September 14th. How

does this affect Starbucks’s transactions?

As always , there have been two effects: we have received $430,100 in cash but we

have also gone into debt for the same amount. Therefore, we would debit Cash

(Cash is an Asset, normal debit balance) and credit Accounts Payable (A/P is a

liability, normal credit balance)

Sept 14

Cash

Accounts Payable

$430,100

$430,100

Example #4:

LiteFitness Company buys Office Supplies on account for $1,345 on November 5. How does

this affect LiteFitness’ transactions?

LiteFitness has acquired some assets (office supplies), increasing/debiting its

Supplies account. However, LiteFitness has also acquired some debt to buy these

supplies, so we need to increase/credit its Accounts Payable account.

Nov 5

Supplies

Accounts Payable

$50,000

$50,000

Need more practice? There are a TON of examples on Chp 3 Powerpoint, slides 11-21!

2. Apply debit/credit rules.

Note: I know memorizing debits and credits is hard, but if you truly focus on the

*SKY HIGH LEVEL* it’s just small details you have to memorize.

Think of credits and debits like credit/debit cards.

When you have a debit card, you start with a $0.00 balance

and put your own money into it for use.

When you have a credit card, you start with some balance (ex: $500) that is not

really your money. You hold on to the money, use it, and pay it back later.

Debits are what you OWN and acquire as a company (assets, expenses,

dividends).

Credits are resources that you are using a company, but are not truly yours

(liabilities, revenue, retained earnings, common stock).

Main Idea:

Debits and Credits should always balance.

It’s always helpful to practice this as it can become confusing!!!

Assets

(Dr)

=

Liabilities + Stockholders Equity

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

(Cr)

Common Stock R/E Revenue Expenses

(Cr)

(Cr)

(Cr)

(Dr)

(Cr)= normal credit account

(Dr) = normal debit account

↓

Dividends

(Dr)

CHP4

1. Apply the revenue recognition principle.

The revenue recognition principle states that companies must recognize revenue in

the same accounting period in which performance obligations are satisfied.

This helps ensure that companies report the correct amount of revenues and expenses in a

given period.

The Unearned Revenue account is a normal credit account used to account for

payments given at a different point in time than when service obligations are

performed. If your customers pay you before you deliver services, that cash is considered

Unearned Revenue (aka a liability) up until you deliver those services to your customer. Let’s

see what that means:

Example 1: Customers pay iPhone Repairs Inc. a total of $1,340 on October 19 for services

that will be completed on October 30.

Oct 19

Cash

$1,340

Oct 30

Unearned Service Revenue

$1,340

Unearned Service Revenue

$1,340

Service Revenue

$1,340

We do not recognize Revenue on October 19 because services have NOT been

conducted, even though cash has been received. Therefore, we must credit Unearned

Revenue. When service obligations are performed on October 30, we can then recognize

revenue by increasing (crediting) Service Revenue and decreasing (debiting) our Unearned

Revenue account.

Example #2: iPhone Repairs Inc. performs $2,345 services on December 30th, but

customers do not pay until January 5th.

Dec 30th

Jan 5th

Accounts Receivable

$100

Service Revenue

Cash

$100

Accounts Receivable

$100

$100

We recognize Service Revenue on December 30th since this was when the

performance obligation was completed. Since the customer did not pay right away, we

debit Accounts Receivable instead of Cash. On January 5th when the customer pays, we

debit Cash and close out/credit our Accounts Receivable account.

2.

Calculate net income from an adjusted trial balance.

Remember, Net Income = Revenues - Expenses

Company Name

Adjusted Trial Balance

November 31, 2021

Cash

Accounts Receivables

Prepaid Insurance

Supplies

Equipment

Equipment- Accumulated Depreciation

Interest Payable

Salaries and Wages Payable

Common Stock

Retained Earnings

Service Revenue

Sales Revenue

Salaries and Wages Expense

Rent Expense

Depreciation Expense

Work:

Revenues:

Service Revenue

$1,782,394

Sales Revenue

$92,980

Total Revenues = $ 1,875,374

Expenses:

Salaries and Wages Expense

Rent Expense

Depreciation Expense

Total Expenses: $ 1,181,387

$495,678

$35,942

$56,013

$104,039

$792,681

$45,000

$284,971

$927,293

$1,024,309

$92,098

$782,394

$92,980

$927,293

$209,094

$45,000

$927,293

$209,094

$45,000

Net Income= $1,875,374 - $1,181,387 = $693,987

3. Prepare adjusting journal entries.

TWO TYPES OF ADJUSTING ENTRIES

Deferrals

- When cash is given/received before any service is done

- Deferrals keep track of changes in the monetary value of assets over small

periods of time

- Prepaid Expenses (payment before use of assets)

- Unearned Revenues (cash received before performance obligation done)

Accruals

- When services are done before any cash is given/received

- Accruals keep track of money movements that are not recorded over small

periods of time

- Accrued Revenues (revenues performed without payment given)

- Accrued Expenses (expenses incurred but not paid)

Deferrals: Unearned Revenue

Example 1: Microsoft Company was paid $25,500 cash by customers for new cell phones

ordered on March 14:

Mar 14

Cash

Unearned Sales Revenue

$25,500

$25,500

We have not earned our Sales Revenue since we have not performed our service

obligations (delivering the cell phones). Therefore, we increase/credit a liability of $25,500

in Unearned Sales Revenue.

However, these cell phones are not delivered until March 31. What is the adjusting entry for

March 31?

Mar 31

Unearned Sales Revenue

Service Revenue

$25,500

$25,500

This adjusting entry recognizes our Service Revenue on March 31 since we have finally

completed our performance obligations. Therefore, we can decrease our liability to

Unearned Sales Revenue since we no longer owe anything to our customers.

IMPORTANT: If the adjusting entry was not recorded to recognize Service Revenue,

Revenues UNDERstated and Liabilities would have been OVERstated. Therefore, Net

Income would be UNDERstated.

Deferrals: Prepaid Expenses

Example 1: Eggo Waffle Company counted $3,095 of Office Supplies on October 16. On

October 30, only $1,000 of supplies were usable. What is the adjusting entry to adjust the

asset Supplies?

Asset Involved: Supplies

How much supplies were used? $3,095 - $1,000 = $2,095 supplies were expensed

October 30

Supplies Expense

Supplies

$2,095

$2,095

This adjusting entry clarifies that we used $2,095 of Supplies, so we decrease our Supplies

asset by $2,095 and incur a debit to Supplies Expense.

IMPORTANT: If this adjusting entry isn’t recorded to decrease Supplies, Assets will be

OVERstated, and Expenses will be UNDERstated. Therefore, Net Income would be

OVERstated.

Example 2: In 2018, Red Airport Car Rentals Inc. had annual Prepaid Insurance on a car for

$1,620. Each month, this Prepaid Insurance decreased as time went by. What is the

adjusting entry to account for the usage of Prepaid Insurance after one month, on January

30, 2018?

Asset Involved: Prepaid Insurance

How much is the monthly expense? $1,620 / 12 months = $135

Jan 30, 2018

Insurance Expense

Prepaid Insurance

$135

$135

This adjusting entry clarifies that we have used one month’s worth of Prepaid Insurance, so

we must adjust our entries to decrease our asset of Prepaid Insurance, creating an expense

in the form of Insurance Expense.

IMPORTANT: If this adjusting entry wasn’t recorded to decrease Prepaid Insurance, Assets

will be OVERstated, and Expenses will be UNDERstated. Therefore, Net Income would be

OVERstated.

(Why would Assets be overstated? Because we would be claiming 12 months of Prepaid Insurance

assets, when in reality we only have 11 months’ worth on January 30,2018.

We wouldn’t have recorded this expense, making our net income appear bigger/higher.)

Accruals: Accrued Interest

Example 1: Honey Bear Company borrows a 12-months notes payable for $9,00 on

April 1 with an annual interest rate of 10%. What is the entry to record monthly Interest

Expense?

Monthly Interest Expense: $9,000 x 0.10 x 1/12 = $75

To account for 1 month of Interest Payable

April 30

Interest Expense

Interest Payable

$75

$75

This adjusting entry ensures that we account for our Interest Expense even though we have

not explicitly paid for it yet. This creates a liability in the form of Interest Payable.

IMPORTANT: Without the adjusting entry to increase Interest Expense and Interest Payable,

our Expenses and Liabilities would be UNDERstated. Net Income would be OVERstated.

Accruals: Accrued Revenues

Example 1: Samuel Car Repairs Inc.. performs its service obligations of $11,285 to

customers that were not billed on or before June 15.

June 15

Accounts Receivable

Service Revenue

$11,285

$11,285

This adjusting entry ensures that our assets (Accounts Receivable) and revenues (Service

Revenue) are recorded even though cash is not exchanged.

IMPORTANT: Without any adjusting entry to increase Service Revenue, our Revenues,

Assets and Net Income would be UNDERstated. Why? Because we wouldn’t have

accounted for this unpaid Accrued Revenue, making our Net Income appear smaller/lower.

Accruals: Accrued Salaries and Wages

Example 1: Gianni Company pays its employees biweekly on Saturdays - the last

paychecks were given on November 20, 2021. The next pay day will be December 4th,

2021. However, Gianni Company prepares monthly financial statements and must record the

Salaries and Wages Expense on November 30th, 2021. Therefore, Gianni Company must

record the adjusting entry for employee work from November 21-30 (10 days).

Employees get paid a total of $1,500 per day, 7 days a week.

(If it’s helpful to visualize, look at a calendar of this year for November and December)

What is the adjusting entry that Gianni must make to record Salaries and Wages Payable for

November 21-30?

$1,500 per day x 10 days = $15,000 total Salaries and Wages Payable

Nov 30

Salaries and Wages Expense

$15,000

Salaries and Wages Payable

$15,000

This adjusting entry keeps track of Gianni Company’s Salaries and Wages Expense even

though they will not pay it within this accounting period. This creates a liability in the form of

Salaries and Wages Payable.

IMPORTANT: Without this adjusting entry to increase Salaries and Wages Expense and

Salaries and Wages Payable, Liabilities and Expenses would be UNDERstated. Net Income

would be OVERstated.

CHP5

1. Interpret sales discounts and sales returns.

Sales Discounts are percentage discounts given off from original prices to customers

for services/goods bought. They usually exist as an incentive to pay customer debts to

companies faster.

For example, a company may give a 2% discount if customers pay within the first ten days of

purchase. This would lead to CREDIT TERMS “2/10, n/30”.

The 2/10 refers to the 2% discount in the first 10 days. Meanwhile, the n/30 means that if a

customer does not pay in the discount period, the Net Amount of sales is due in 30 days.

Sales Returns are returns of sales that customers give back to the company - this is

taken off from revenues and from customer’s debt. Sales Returns usually are a result of

faulty products, or the realization that a customer has ordered excess products.

Sales Allowances are also discounts given to customers that agree to keep faulty

products for a certain discount on the original price.

2. Calculate cost of goods sold under a periodic system.

Company Name

Cost of Goods Sold

For the Period Ending December 31, 2028

Beginning Inventory, Jan 1st

+ Purchases

$4,540

- Purchase Returns and Allowances

($3,400)

- Purchase Discounts

($270)

+ Freight In Costs

$230

-----------------------------------------------------------Cost of Goods Purchased

Cost of Goods Available For Sale

Ending Inventory, Dec 31

Cost of Goods Sold

$5,000

+ $1,100

---------$6,100

($3,500)

---------$ 2,600

CHP6

1. Calculate cost of goods sold or ending inventory using FIFO or LIFO.

Remember, FIFO, LIFO and Average. Cost are used to calculate COGS,

not Ending Inventory!

Date

Jan. 1

Feb. 15

April. 30

May. 8

TOTAL

Explanation

Beginning Inventory

Purchase

Purchase

Purchase

Units

150

100

300

500

= 1,050

Unit Cost

$10

$11

$12

$13

Total Cost

$1,500

$1,100

$3,600

$6,500

= $12,700

Given: 450 units were sold

Example 1: Find COGS and Ending Inventory under FIFO.

FIFO= first in, first out

Part 1. Find COGS. We must find the cost of exactly 450 units sold, starting from the

beginning of the period.

Work:

Jan 1

150 x $10 = $1,500

Feb 15

100 x $11 = $1,100

April 30

200 x $12 = $2,400

TOTAL = 450 units = $5,000

450 units sold = $5,000 COGS

Part 2. Find ending inventory.

Work:

1050 total units - 450 units sold = 600 units of ending inventory

May 8

500 x $13 = $6,500

April 30 100 x $12 = $1,200

TOTAL =600 units = $7,700

(notice that this is whatever is left after accounting for the units in COGS from Part 1)

600 units = $7,700 Ending Inventory

Let’s double check our work.

$5,000 COGS + $7,700 Ending Inventory = $12,700 Total

Correct!

Example 2: Find COGS and Ending Inventory under LIFO.

LIFO= last in, first out

Part 1: Find COGS. We must find the cost of selling exactly 450 units, starting from the end

of the period.

Work:

May 8 450 x $13 = $5,850 COGS

Part 2: Find Ending Inventory.

Work:

1050 total units - 450 units sold = 600 units of ending inventory

Jan. 1

Feb. 15

April. 30

May 8

TOTAL

150 x $10 = $1,500

100 x $11 = $1,100

300 x $12 = $3,600

50 x $13 =

$650

= 600 units = $6,850 Ending Inventory

Let’s double check our work.

$5,850 COGS + $6,850 Ending Inventory = $12,700 Total

Correct!

2. Calculate cost of goods sold and gross profit using average cost

Date

Explanation

Jan. 1

Beginning Inventory

Feb. 15 Purchase

April. 30 Purchase

May. 8

Purchase

TOTAL

Given: 450 units were sold

Units

150

100

300

500

= 1,050

Unit Cost

$10

$11

$12

$13

Total Cost

$1,500

$1,100

$3,600

$6,500

= $12,700

Part 1: Find COGS.

Work:

Total Price / Total Units = $12,700 / 1050 = $12.10

$12.10 x 450 units sold = $5,445 COGS

Part 1: Find Gross Profit.

Gross Profit = Net Sales - Cost of Goods Sold

Given, Net Sales= $7,500

Work:

Gross Profit = $7,500 Net Sales - $5,445 COGS

Gross Profit = $2,055

CHP7

1. Prepare a bank reconciliation.

What is a bank reconciliation?

It is basically a document that manages the equivalency of the cash amount between a

company’s books and a bank statement. It makes sure that both books are recording the

same number.

Because of time gaps and errors, these two numbers might not be the same. We are not

totally concerned about this, as long as we can figure out why.

Representation of a Bank Reconciliation:

Company Name

Bank Reconciliation

February 29, 2020

Cash Balance per Bank Account

Add: Deposits In Transit

Less: Outstanding Checks

---------------------------------------------Adjusted Cash Balance Per Bank

Cash Balance per Company Books

Add: EFT Checks

Less: NSF Checks

Less: Bank Charges & Fees:

-----------------------------------------------Adjusted Cash Balance Per Books

Adjusted Cash Balance Per Bank = Adjusted Cash Balance Per Books

Deposits In Transit: Checks that the company wants to add to its bank amount, but

have not been received by the bank yet.

Outstanding Checks: Checks that the company uses to buy things, so the company

expects this amount to be deducted from its cash balance.

EFT Checks: Checks that are transferred electronically, so the company’s books do

not record this automatically. Therefore, they must be adjusted to the book balance.

NSF Checks: Checks that the company has recorded as received from customers.

However, customers did not have Sufficient Funds to pay the amount, so the bank is

unable to give the money to the company.

Bank Charges & Fees: Fees that the bank automatically charges to the bank

account, so book balance must be adjusted to reflect this.

2. Calculate the amount of cash to borrow based upon a cash budget.

Often, a company sets a minimum amount of money that it must have in its hands to

cover all expenses over a specific period of time. If profit is not enough to cover such

expenses, companies often borrow money and pay it back later, with interest fees.

Company Name

Cash Budget

For the Year Ending December 31, 2029

Beginning Cash Balance

Add: Cash Receipts

Collection From Customers

Sales of Short Term Investments

= Total Available Cash

Less: Cash Disbursements

Salaries and Wages

Selling Expenses

Administration Expenses

Payments to Suppliers

= Available Cash Over Disbursements

Financing

Add: Borrowing

Less: Repayments

= ENDING CASH BALANCE

{ The ENDING CASH BALANCE from the end of one year is also the beginning cash

balance of the next period }

Summary of Cash Budget:

Beginning Balance

+ Total Cash Receipts

= Total Available Cash

- Cash Disbursements

= Available Cash Over Disbursements

+ Financing (Money borrowed - repayments)

= TOTAL CASH BALANCE

Example:

Example 1: Given the balances, prepare a Cash Budget for Clean Soap Company for

the Year Ending December 31, 2029:

Beginning Balance: $35,000

Collection From Customers: $49,600

Salaries and Wages Expense: $56,000

Payment to Suppliers: $15,050

Financing Repayments from last accounting period : $350

Clean Soap Company

Cash Budget

For the Year Ending December 31, 2029

BEGINNING BALANCE ($35,000)

Add: Cash Receipts

+ Collection from Customers ($49,600)

= Total Available Cash

Less: Cash Disbursements

- Salaries and Wages Expense ($56,000)

- Payment to Suppliers: $15,050

--------------------------------------------------------------------$13,550 Available Cash Over Disbursements

FINANCING

Add: Borrowed Money ($0)

Less: Financing Repayments ($350)

= $13,200 TOTAL CASH BALANCE

Example 1 (cont): Clean Soap Company wants to always have a minimum cash

balance of $15,000 to cover all of their expenses at the end of the year of 2029.

Do they need to borrow money? If so, how much?

Clean Soap’s total cash balance is $13,200, which is lower than the minimum of $15,000.

Therefore, the company must borrow $1,800 ($15,000 - $13,200).

Clean Soap Company

Cash Budget (partial)

For the Year Ending December 31, 2029

$13,550 Available Cash Over Disbursements

FINANCING

Add: Borrowed Money ($1,800)

Less: Financing Repayments ($350)

= $15,000 TOTAL CASH BALANCE

CHP8

1. Prepare the adjusting entry to record the estimate of bad debt expense.

Bad Debt Expense: A normal debit account that companies use to estimate and record the

amount of money expected to never be received from owing customers.

Why do they do this? Because no matter how careful you are, there will always be a few

customers who will not pay.

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts: A contra-asset normal credit account used to put aside an

allowance for uncollectibles.

Ex 1: On February 1st DMW Shoes Company estimates that out of their total sales, $45,100

in receivables will not be collected. Make an entry to record this. Entry for Audio Supply:

Feb 1st

Bad Debt Expense

$45,100

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts

$45,100

2. Calculate the duration of a note receivable given the interest rate and interest

revenue.

Formulas Needed

Annual Interest Expense = Notes Receivable x Interest Rate

Time Passed In Years = Total Interest Revenue / Annual Interest Expense

Duration of Notes Receivable = Time Passed In Years + Years Left

Example 1: Blue Jeans Inc. is holding a $8,500 Notes Receivable with 11% Interest Rate

that has already accrued interest revenue of $2,805. If there are 4 years left on the notes

receivable, what is the total duration of the note?

Annual Interest Expense = Notes Receivable x Interest Rate

Annual Interest Expense = $8,500 x 0.11

Annual Interest Expense = $935

Total Interest Revenue / Annual Interest Expense = Time Passed In Years

$2,805 / $935 = 3 years

So, the notes receivable has accrued interest revenue for 3 years and has 4 years left on its

life.

Years Passed + Years Left = Duration of Notes Receivable

Therefore, the Notes Receivable has a duration of 7 years.

CHP 9

1. Identify items classified as property, plant, and equipment.

Plant Assets:

- Have physical substance

- Used in business operations (not intended for sale).

- Expected to provide some sort of service to the company

AKA: Property, Plant and Equipment (including land)

2.

Calculate depreciation expense and accumulated depreciation using

straight-line depreciation.

Basic Formulas:

Original Cost - Salvage Value = Depreciable Cost

Depreciable Cost ÷ Useful Life (usually in years) = Depreciation Expense

Example 1:

Company truck bought for $7,500. A salvage value of $800 is expected. The useful life is

calculated to 5 years. What is the annual depreciation expense?

$7,500 - $800 = $6,700

$6,700 ÷ 5 years = $1,340

Annual Depreciation Expense = $1,340

Example 1 (cont):

What is the Accumulated Depreciation after two years of the truck’s useful life?

Accumulated Depreciation = Annual Depreciation Expense x Time in Years

Accumulated Depreciation = $1,340 x 2 years

Accumulated Depreciation = $2,680

CHP 10

1. Define a current liability.

A current liability is a debt that a company owes and expects to pay within one year (it

could also be within one operating cycle, but JP almost always mentions it as ‘within one

year’ because that’s more common in the business world).

Current liabilities also include debt payments that are a portion of a long-term liability.

For example, you may have a house mortgage of $540,000 that you expect to pay back

within 30 years - with a yearly payment of $18,000. Your current liability for each year would

be $18,000 while your long term liability would be the entire $540,000.

2.

Prepare journal entries associated with notes payable.

What is a Note Payable (also written as N/P ) ?

A note payable is basically a legal and documented promise that a debt will be paid at

some point in the future. Like Accounts Payable (also written as A/P ), a Notes Payable is

a liability and has a normal credit balance. Unlike Accounts Payable used for short term

debts however, N/P are usually for long term debts. Why separate these two accounts?

It’s clearer to separate your debts, especially when you have an important $1,000 due in one

month and a not-so-urgent $10,000 due in 3 years.

Also, Notes Payable usually accrues interest, while A/P does not. Interest rates are stated

on a yearly percentage basis. So, accounting for Notes Payable includes keeping track of

the money borrowed and the interest gained on the money borrowed. Let’s see what this

means:

Example 1: Warren Buffett lends a $154,000 12% 10-month note to Professor PJ on

November 1, 2021. Entry for Professor PJ to record the debt:

Nov 1, 2021

Cash

$154,000

Notes Payable

$154,000

Example 2: Professor PJ prepares quarterly financial statements. To account for paying the

interest expense on the N/P, prepare the adjusting entry made on December 31, 2021:

Interest Payable: Principal Amount x Annual Interest Rate x Time Passed

Interest: $154,000 x 0.12 x (2/12)= $3,080

(To account for interest for the month of Nov and Dec)

Dec 31, 2021

Interest Expense

Cash

$3,080

$3,080

Example 3: Professor PJ pays the principal amount and the rest of the interest gained on

the maturity date. Entries for Professor PJ:

We must 1) find the maturity date, and then 2) update the interest payable, and finally 3)

make an entry for paying the full amount.

1) Finding Notes Payable Maturity Date, when counting by months.

Notes Payable was signed on November 1, 2021. This is a 10-month note, so 10

months starting from November 1,2021:

Dec 1st, 2022 -> Jan 1st, 2022-> Feb 1st, 2022 -> March 1st, 2022 -> April 1st, 2022

-> May 1st, 2022 -> June 1st, 2022 -> July 1st, 2022 -> August 1st, 2022 -> Sept 1st,

2022

Maturity date is September 1st, 2021!

2) Update Interest.

We have already accounted for two months of interest in the last example, so we must

account for the remaining eight months (Jan-Sept)

Interest: $154,000 x 0.12 x (8/12) = $12,320

Sept 1,2022

Interest Expense

Interest Payable

$12,320

$12,320

3) Making entries for Professor PJ to pay full amount:

Sept 1, 2022 Notes Payable

Interest Payable

Cash

$154,000

$12,320

$166,320

3. Determine proper classification for a note payable on the balance sheet.

As explained earlier (Chp 10 #1), a Note Payable is a Long Term Liability.

Company Name

(partial) Balance Sheet

As of Dec 29, 2035

★ ASSETS

★ LIABILITIES

A) Current Liabilities

B) Long Term Liabilities

a) Notes Payable

★ STOCKHOLDERS EQUITY

4.

Identify the correct journal entries associated with current liabilities.

What Are Current Liabilities?

For our class, there are officially four main types of Current Liabilities

(I categorize them into five to make it faster to understand):

Notes Payable, Unearned Revenues, Sales Taxes Payable, Payroll and Payroll Taxes.

Since we already went over Notes Payable (Chp10 #2), we will start with Unearned

Revenues.

Unearned Revenue is basically money paid up front for services/goods to be

delivered at a future date. Since it is a liability, Unearned Revenue has a normal credit

balance. Unearned Revenue can be split up into different accounts: Unearned Service

Revenue, Unearned Ticket Revenue, Unearned Sales Revenue, etc.

For example, let’s say you order clothes online from Fashion Nova. You pay up front and

trust that Fashion Nova will indeed send your clothes on the date they promise. Therefore,

for Fashion Nova, the money you send them with your credit card is Unearned Revenue

because they have yet to fulfill their promise.

Furthermore, this money is a liability - Fashion Nova has cash, but they owe you something.

Side Note: I have a grudge against Fashion Nova, they don’t keep this promise very well. Anyways...

Example 1: You pay $500 for clothes from Fashion Nova on June 20 2020. Entry for

Fashion Nova:

June 20, 2020

Cash

$500

Unearned Sales Revenue

$500

Example 2: Surprisingly, Fashion Nova does indeed deliver your clothes, on August 5, 2020.

Now the $500 is not a liability anymore, since they have fulfilled their performance

obligations. They can recognize the sale as revenue now! So we deduce the amount from

Unearned Sales Revenue (as a debit) and move the cash into its corresponding Revenue

account :

August 5th, 2020

Unearned Sales Revenue

Sales Revenue

$500

$500

Sales Taxes Payable

Sales Taxes Payable records sales tax liability that a company must pay to the

government. Customers pay sales taxes through their purchases - companies simply grab it

from customers’ hands and slide it over to the government. Sales Taxes are not revenue

because companies do NOT keep this money, so it must be accounted for with a different

account. Sometimes, companies explicitly separate sales taxes from revenue, sometimes

they don’t. Let’s see what that means:

Example 1: Kroger collects $40,000 total sales for February 29,2020.

Sales taxes is 8% of total sales. Entry for Kroger:

IMPORTANT: Sales tax is given as a percentage of total sales!

Sales Taxes= 8% of $40,000 = 40,000 x 0.08 = $3,200

Entry:

Feb 29, 2020

Cash

$43,200

Sales Revenue

$40,000

Sales Taxes Payable

$3,200

Example 2: Kroger collects $118,800 as the amount of revenue and sales tax on

February 29,2020. This includes 8% sales taxes. In this case, we must find what

amount is sales tax and what amount is sales revenue.

In this case, we can’t calculate 8% of $118,800 to get sales taxes because total sales is not

given. Instead, the $118,800 represents the sales revenue and sales taxes added together.

The textbook gives an equation to get around this:

Textbook Equation:

Revenue = Amount of Revenue and Sales Tax / 1 + Sales Taxes as a Decimal

Amount of Revenue and Sales Tax = $118,800

Sales Taxes as a Decimal = 8% -> 0.08

Revenue = $118,800 / 1 + 0.08

Revenue = $118,800 / 1.08

Revenue = $110,000

Sales Taxes = $110,000 x 0.08 = $8,800

Check your work:

$110,000 + $8,800 = $118,880 Correct!

Entry:

Feb 29, 2020

Cash

$118,800

Sales Revenue

$110,000

Sales Taxes Payable

$8,800

Why Do We Need This?: -----------------------------------------------------------------------------Now, in my opinion, this equation given in the textbook is vague and confusing because you

feel like you have no idea where these numbers come from. But don’t worry, I will now

smoothly explain where it comes from:

$118,800 accounts for both revenue and for 8% (or 0.08) of revenue as sales taxes.

It’s like accounting 100% of revenue and ADDING 8% of revenue on top of that to account

for sales taxes.

In a math equation, we can say:

$118,800 = 100% Revenue + 8% Revenue

(let’s write this as decimals instead of percentages)

8% -> 0.08

100% -> 1.00

So,

$118,800 = 1.00Revenue + 0.08 Revenue

(Remember, 1.00 x anything = 1.00 Therefore 1.00 x R = R.)

Where Revenue is the principal amount we are trying to find. Let’s rewrite this with variables:

$118,800 = 1.00Revenue + 0.08 Revenue

$118,800 = 1.00R + 0.08 R

$118,800= 1.08R

Therefore, we arrive at the equation given by the textbook. To find revenue from total sales

and sales taxes received, we must:

Revenue = Amount of Revenue and Sales Tax / 1 + Sales Taxes as a Decimal

(divide both sides by 1.08 to find R)

$118,800 /1.08 = 1.08R / 1.08

$110,000 = R

Since Sales Revenue is $110,000 and there is a 8% sales taxes, we can find sales taxes as

we did before:

$110,000 x 0.08 = $8,800

$110,000 + $8,800 = $118,800

End of Explanation-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Does it make sense? Maybe not, it’s math after all.

However, following along and calculating the variables along with the example helps out.

Cover up the answer and try to get it on your own!

Let’s try again, with another example.

Ex3: Kroger receives $98,100 of revenue and sales taxes on March 1,2020. Sales

taxes are 9%. Entry for Kroger:

Revenue = Amount of Revenue and Sales Tax / 1 + Sales Taxes as a Decimal

Revenue = $98,100 / 1 + 0.09

Revenue = $98,100 / 1.09

Revenue = $90,000

Sales Tax = $90,000 x 0.09 = $8,100

Entry for Kroger:

March 1, 2020

Cash

$98,100

Sales Revenue

$90,000

Sales Taxes Payable $8,100

Payroll and Payroll Taxes

Payroll and Payroll Taxes are categorized by the textbook into one thing, but there are two

different entries associated with them. So, it’s better said as Salaries and Wages Expense

(aka Payroll) and Payroll Taxes.

Salaries and Wages Expense (Payroll) accounts for:

- FICA taxes

- Federal Income Taxes

- State Income Taxes

- Union dues

- Medicare/Healthcare dues

- Salaries and Wages Payable

Payroll Taxes Expenses account for:

- FICA taxes (yes, accounted for again)

- Federal Unemployment Taxes

- State Unemployment Taxes

And that’s it! Just remember the general gist of the difference between the two lists,

and you will be set to answer any questions. This is just plug and chug. Let’s try!

Example #1: Avalon Regal Company needs to record its Payroll and Payroll Taxes.

Here are a list of their dues as of March 2nd, 2020:

Federal Income Tax Payable: $4,000

State Income Tax Payable: $5,500

Federal Unemployment Tax Payable: $450

State Unemployment Tax Payable: $340

Union Dues Payable: $145

Medicare Tax Payable: $1,780

Salaries and Wages Payable: $55,000

FICA Taxes Payable: $6,700

Part 1) Make entry for Avalon’s Payroll (Salaries and Wages Expense):

Mar 2, 2020

Salaries and Wages Expense

$73,125

FICA Tax Payable

$6,700

Federal Income Tax Payable

$4,000

State Income Tax Payable

$5,500

Union Dues Payable

$145

Medicare Tax Payable

$1,780

Salaries and Wages Payable

$55,000

All you need to do is write down the corresponding dues as credits (because they are

liabilities). Then, you add up all the credits to get your total Salaries and Wages Expense as

a debit. Let’s try again with Payroll Taxes:

Part 2) Make entry for Avalon’s Payroll Taxes:

Mar 2, 2020

Payroll Taxes Expense

$11,040

State Unemployment Tax Payable

$340

Federal Unemployment Tax Payable

$4,000

FICA Tax Payable

$6,700

Easy as 1,2,3! Again, all you need to do is:

1) Identify the taxes you must account for

(Salaries and Wages Expense vs Payroll Taxes)

2) Record all dues as credits.

3) Add up the total amount of credits to record your debit account. Your debit account

will always be either Salaries and Wages Expense or Payroll Taxes Expense

If you need a little more practice, WileyPlus Chapter 10 HW Problem #3 has a very similar

problem to this.

5. Calculate the selling price of a bond.

HELP! WHAT IS A BOND???

A bond is basically a type of notes payable, that’s it! Bonds are used to borrow money

from investors. Bonds are legally documented, and they accumulate interest. When a

company “issues bonds”, it is GIVING bond certificates in exchange for cash. Bonds

are given in small denominations, so they are relatively cheap and attractive to

investors.

So, if a company issues 10 bonds at $1,000 each, it is borrowing $10,000 in cash

(10 bonds x $1,000 = $10,000).

The investor that buys the bond is called the bondholder; they are lending money.

Companies who issue bonds are borrowing money for a period of time.

But the problem is, that borrowed money is due back some 20 or 30 years in the future. Like

JP says, there’s a LOT of things that can happen in that period of time.

One of the things that can happen in that time is that the bondholder can sell his bonds.

This means that a third party buys the bond at a selling price, and the bondholder gets the

original debt back. The bondholder no longer has to worry about the company paying him

back.

Selling price of a bond is usually stated as a percentage of the face value of the bond.

Ex 1: Phil Knight issues one bond, with a face value of $4,000 to his trusted investor

Mark Parker. One week later, Mark Parker decides to sell this bond at 98 (meaning at

98% of the face value) to Andrew Campion. How much money does Mark Parker

receive when selling this bond? In other words, what is the selling price of the bond?

Well, the face value of the bond is $4,000. Parker sells it for 98%.

$4,000 x 0.98 = $3,920.

The selling price of the bond is $3,920.

So, Mark Parker lent $4,000 to Phil Knight in the form of a bond certificate.

Instead of waiting to receive back his $4,000 , Mark Parker sells his bond for $3,920 to

Andrew Campion. Mark Parker no longer has to wait for his $4,000, and Andrew Campion

receives the bond certificate in his hands.

Phil Knight no longer owes $4,00 to Mark Parker. Instead, Knight owes it to Andrew

Campion, as he is the new bondholder.

Doesn’t it seem a bit chaotic?

Yes, and this happens thousands of times every single day.

Companies issue bonds (borrow money), and this money gets moved around

endlessly between investors. But more on that later...

6.

Based on interest rates, determine if a bond would be sold at a premium

(above face value) or a discount (below face value). !!!!

Why Do We Need This?: -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------Money and the stock market are very complicated worlds, especially when you realize

that all currency in this world depends on our perception of its value. If you perceive

silver as more valuable than gold, no one can convince you otherwise. If one day you decide

that a $100 bill is not worth anything more than a piece of paper, then you perceive its value

as zero dollars. Fortunately, as a society, we have come to some agreement about the

monetary value of paper money.

As explained earlier, bonds accrue interest. Interest payments are usually paid annually, as a

percentage of the principal amount of a bond.

In the money market world (however you want to call it), interest rates are different for all

kinds of bonds. How do investors decide where to put their money?

Well, it partially depends on the market interest rate, which we as a society have agreed

upon. Well, the society within the money market world.

Let’s say that on a given day, the market interest rate is 10%.

This means that if a company is giving you a contractual interest rate of 10%, you will

receive 10% of the money you lent as interest payments every year. If you lent $100,000 to

the company, you will receive $10,000 every year as an interest payment.

But what if another company is offering you a contractual interest rate of 12%? It’s higher

than the market interest rate, so you’d be an idiot not to lend them your money.

If a third company is offering 8%, not many people will be lining up to lend money.

Again, this is because AS A SOCIETY, investors have decided that 10% is the

“valued” market interest. Anything more sells like hot bread, anything less is not

really looked at. It’s a bit arbitrary, but investors depend on the market interest rate to

compare their investment options.

SO, to gain some leverage against this weird arbitrary market interest rate, companies

issue bonds at a DISCOUNT or at a PREMIUM.

End of Explanation: -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Bonds at a Discount:

Let’s go back to the company that is offering a contractual interest rate of 8% rather than

the market interest rate of 10%.

If this company continues to issue bonds at a low 8%, not many people will be willing to lend

their money. They need to change something.

What they usually do is sell their bond at a discount (as a percentage). What does this

mean?

A discount of 2% would bring the $100,000 face value down to $98,000.

Investors would only have to pay $98,000 up front, rather than the full $100,000.

The catch is that at the end of the life of the bond, the company still has to pay back the full

$100,000.

Therefore, the investor is happy that it is getting a discount up front and still getting

the full amount at the maturity date of the bond.

Bonds at a Premium:

Let’s go back to the company that is offering a contractual interest rate of 12% rather than

the market interest rate of 10%. In this case, the company has some power since there are

so many people lining up to lend money. How do they take advantage of this?

They will increase the bond price by applying a premium to the face value

(as a percentage).

A premium of 3% would bring the $100,000 face value up to $103,000. Investors have to pay

$103,000 up front, rather than just $100,000. However, the investors enjoy higher interest

rates.

At the maturity date of a bond, the company will only have to pay back the $100,000.

In very basic words:

When a company offers a contractual interest rate LOWER than the market interest rate:

1. The investor has more leverage

2. The company lowers the bond price in the form of a DISCOUNT

3. The investor enjoys a full return of the face value at the maturity date of the bond,

regardless of the low interest rate.

When a company offers a contractual interest rate HIGHER than the market interest rate:

1. The company has more leverage

2. The company raises the bond price in the form of a PREMIUM

3. Investors enjoy a higher interest rate, and get paid back the original face value at the

maturity date of the bond.

And that's it! It’s like negotiating a deal. There’s gotta be a compromise :)

7. Prepare journal entries to record bond transactions. !!!

FOR THIS CLASS, bond transactions take one of three forms: issuing bonds (with

premium and discounts), calculating interest accrued, and the redemption of bonds. The first

two are easy, and the third one is even easier if you follow the steps. Let’s get to it:

Issuance of Bonds:

Bonds can be issued at face value, or as we discussed earlier, at a discount or premium.

Ex 1: XYZ Company issues a $100,000 9%, 10-year bond AT FACE VALUE on January 1,

2021. This means that it receives cash (debit) and gains a liability (credit). Entry:

Jan 1,2021

Cash

$100,000

Bonds Payable

$100,000

Ex 2: XYZ Company issues a 10-year, 9% DISCOUNTED bond of $280,000 at 97

(percentage of face value) on January 2nd, 2021. Entry:

Jan 2nd, 2021

Cash

$271,600

Bonds Payable

Discount on Bonds Payable

$8,400

$280,000

Bond Price (Cash paid) = $280,000 x 0.97 = $271,600

Bonds Payable is equal to the original Face Value of $280,000.

Discount on Bonds Payable = Face Value - Discounted Bond Price

Discount on Bonds Payable = $280,000 - $271,600 = $8,400

Ex 3: XYZ Company issues a $189,000 9% 20-year bond at a PREMIUM at 103

(percentage of face value) on January 3rd, 2021. Entry:

Jan 3rd, 2021

Cash

$194,670

Bonds Payable

$189,000

Premium on Bonds Payable

$5,670

Bond Price (Cash paid) = $189,000 x x 1.03 = $194,670

Bonds Payable is equal to the original Face Value of $189,000

Premium on Bonds Payable = Bond Price - Bonds Payable

Premium on Bonds Payable = $194,670 - $189,000 = $5,670

Interest Accrued on Bonds:

Interest Accrued on bonds is the same story as interest on notes payable!

Example 1: XYZ Company issued a $96,000 9% 10-year bond on July 3rd, 2022. What will

be the adjusting entry to account for yearly interest payable?

Annual Interest= $96,000 x 0.09 = $8,640

July 3rd, 2022

Interest Expense

Interest Payable

$8,640

$8,640

Redemption of Bonds:

The redemption of bonds simply means the paying back of a bond debt. When a company

issues a bond it is borrowing money, as we saw earlier. The redemption of the bond takes

place when the company pays back the amount.

Anyways, we need to know two important vocabulary words to understand this:

The redemption price is the money that the company pays back to the bondholder.

This is usually given as a percentage.

Ex: “Redemption price is: $500,000 at 104” simply means that the company paid 104% of

$500,000.

In other words, they paid: $500,000 x 1.04 = $520,000

The carrying value of a bond is the net amount of a bond plus any premium or minus

any discount. It is the monetary VALUE of the bond. You probably won’t have to

calculate carrying value when making entries, they will usually be explicitly given.

So, if you pay a redemption price HIGHER than the carrying value of a bond, you are

paying more money than the bond’s value. This is a loss in sales.

If you pay a redemption price LOWER than the carrying value of a bond, you are paying

less money than the bond’s value. This is a gain in sales.

Redemption of bonds requires you to make entries to FOUR accounts. Let’s get to work:

The Only Steps You Need To Do:

1) Make the first two entries, for closing out Bonds Payable and for Cash paid.

2) Figure out if the Carrying Value or Redemption Price is greater.

a) If Carrying Value - Redemption Price = Positive Number, GAIN!

i)

Gain on Redemption is a CREDIT

b) If Carrying Value - Redemption Price = Negative Number, LOSS!

i)

Loss on Redemption is a DEBIT

3) What is left?

a) If there is a hanging debit, close it as a Premium on Bonds Payable

b) If there is a hanging credit, close it as a Discount on Bonds Payable

Example 1: CocaCola Company redeems $600,000 face value, 9% bonds on July 15th,

2022, at 102. The carrying value of the bond at the redemption date was $585,000. The

bonds pay annual interest, and the interest due on July 15th has already been accounted

for:

Part 1) First two entries: To deduce Bonds Payable owed and Cash paid.

Bonds Payable : $600,000

How much is paid in cash? $600,000 x 1.02 = $612,000

July 15th,2022

Bonds Payable

Cash

$600,000

$612,000

Part 2) Gain or Loss?

Carrying Value = $585,000

Redemption Price = $600,000 x 1.02 = $612,000

Carrying Value - Redemption Price = $585,000 - $612,000 = - $27,000 (There is a loss!)

Write down your gain/loss as an entry. Gain as a credit, loss as a debit.

July 15th,2022

Bonds Payable

Cash

Loss on Bond Redemption

$600,000

$612,000

$27,000

Part 3) Take care of the hanging credit/debit.

There is a hanging credit for $15,000.Therefore, this will be closed out as a discount.

Finalized Entry:

July 15th,2022

Bonds Payable

$600,000

Cash

$612,000

Loss on Bond Redemption

$27,000

Discount on Bonds Payable

$15,000

Need more practice? WileyPlus CHP10 HW Problem #9 has similar questions to this! Don’t

forget to follow along with the steps!

CHP 11

1. Interpret the corporate characteristic of limited liability.

Limited liability of corporation stockholders means that stockholders of a company are

only liable for the money they invest. For example, if you invested in a company you legally

cannot claim the owner’s personal assets (unless some sort of fraud took place).

2.

Understand the journal entry to record the issuance of common stock and

calculate total shares issued.

What is Common Stock? So many weird words...

Common Stock is a fancy word that refers to the partial ownership of a company. If a

company issues 25% of its common stock to you, you own 25% of the actual company.

Most companies however, issue thousands and thousands of stocks so these percentages

of ownership decrease. Maybe you have 1,000 stocks of a company, but if the total amount

issued is 1 million, you don’t have a lot of ownership.

Companies issue stock to raise money. We are not really learning why this happens, but

more so how to record the events. So it can get confusing because you are given a lot of

information and what we mostly do is just plug in numbers into accounts.

So, to make it easier, just try to focus on the big idea: We are just recording the

issuance of stock. Plug and Chug. What number goes where?

The Par-Value of a stock is merely a legally stated value of a company’s stock. It has

nothing to do whatsoever with the market value. It’s barely used today, but it helps

understand why we have the Excess in Par Value account. Also, it never changes.

Today, most stocks are No-Par Value stock that have a stated value given by the

company’s board of directors.

Par-value is given by a LEGAL charter, while Stated value is given by a company’s

board of directors. That’s really the only big difference between the two. It’s not that big

of a deal, but we do have different accounts for them. Let’s see how this works out…

Example 1 (par value):

Facebook issues 1,000 common stock shares with $1 par value per share on June 3rd,

2022. Entry:

Whenever we issue stock by its par value, we record the cash we receive and we record the

Common Stock now belonging to our shareholders.

Amount of Shares x Par Value = Amount of Cash of Shares Issued at Par Value

1,000 shares x $1.00 Par Value = $1,000 cash of shares issued at par value

June 3rd, 2022

Cash

$1,000

Common Stock

$1,000

Example 2 (par value):

Facebook issues 1,000 common stock shares with $1 par value at $6 cash per share on

June 4th, 2022. Entry:

In this case, we issued common stock at a higher price than its par value per share. For

legal purposes, we record:

1) Total Par Value of the Shares as Common Stock, like Example #1.

2) Excess of the cash received as a credit to Paid-in Capital Excess of Par Value-Common

Stock.

This is simply to record like we did in the last example, AND also account for the excess

cash received. Nothing fancy, nothing complicated.

If you were dealing with preferred common stock, you would credit to Paid-in Capital Excess of Par Value-Preferred Stock.

Amount of Shares x Par Value = Amount of Cash of Shares Issued at Par Value

1,000 x $1.00 = $1,000 Common stock

But, we issued the shares at $5 each!

Amount of Shares x Cash Per Share = Cash Received from Issuance of Shares

1,000 x $6.00 = $6,000 Cash received.

So, the shares were originally at $1 but we sold them for $6. What is the excess?

Cash Received - Common Stock = Paid-In Capital Excess of Par Value

$6,000 - $1,000 = $5,000

June 4th, 2022

Cash

$6,000

Common Stock

Paid-in Capital Excess of Par ValueCommon Stock

$1,000

$5,000

Example 3 (stated value):

Facebook issued 1,000 shares of No-Par-Value stock with a stated value of $3 for cash at $5

per share on June 5th, 2022.

June 5th, 2022

Cash

$5,000

Common Stock

$3,000

Paid-in Capital in Excess of Stated Value- $2,000

Common Stock

Example 4 (no par value, no stated value):

I included this example because in one of his lectures, JP went over this example that was written in

the PowerPoint and pointed out that the answer given was wrong. Careful when you see this in the

powerpoint or anywhere else, but here I include the right answer (obviously lol):

Facebook issues No-Par stock that has no stated value. It issued 5,000 shares at $6 per

share for cash on June 6th, 2022. Entry:

Since we have no par value or stated value, we do not make a credit to Common Stock. All

of our credit simply goes to our Paid-in Capital in Excess of Par Value- Common Stock

account.

June 6th, 2022

3.

Cash

Paid-in Capital in Excess of Stated Value Common Stock

$30,000

$5,000

Calculate preferred stock dividends.

Okay, but what is Preferred Stock? Is it not the same as Common Stock?

Preferred stock is a bit similar to common stock because they are both issued to investors.

However, Common stockholders have voting rights in a company - meaning they have a say

in big decisions.

Preferred stockholders have no voting rights, BUT they do get their dividends paid

earlier than common stockholders. Preferred stocks are generally more expensive,

too.

Preferred stock dividends are paid annually, and as a percentage of preferred stock

totality. If a company skips a year of its preferred dividend payments, this payment is

accumulated until the company declares dividends. This is known as cumulative preferred

dividends. Whatever is left AFTER paying preferred dividends, is paid to common

stockholders.

Example 1:

Honda Cars Company pays preferred dividends on 6% of $567,000 preferred stock. How

much are they paying?

6% of $567,000 = 0.06 x $567,000 = $34,020 paid.

Example 2:

Honda Cars Company opened its company on January 1st, 2018. It annually pays 21% of

$649,000 on CUMULATIVE preferred dividends. They do not declare dividends in 2018,

2019, or 2020. In 2021, they declare $700,00 of dividend payments. How much will preferred

stockholders get paid? How much will common stockholders get paid?

Basic Steps:

1) How many years of preferred dividends are we paying? How much cash is that?

2) How much cash is left after paying preferred dividends? This is how much common

stockholders will get paid.

Part 1)

The company did not declare dividends in 2018, 2019, 2020 but did declare in 2021. Since

we are dealing with cumulative preferred dividends, we must pay preferred dividends for ALL

FOUR YEARS.

Annually, we will pay 21% of $649,000

$649,000 Preferred Stock x 0.21 = $136,290

$136,290 x 4 years = $545,160 for Four Years of Preferred Dividend Payments

Part 2)

Honda Cars had declared $700,000 of dividend payments, so we have to figure out how

much is left after paying preferred stockholders.

$700,000 - $545,160 = $154,840

Therefore, $154,840 is paid to common stockholders.

Example 3:

Honda Cars Company opened its company on January 1st, 2018. It annually pays 21% of

$550,000 on NON-CUMULATIVE preferred dividends. They do not declare dividends in

2018, 2019, or 2020. In 2021, they will pay the dividends due. How much will Honda Cars

pay to its preferred stockholders?

Well, dividends are non-cumulative so Honda Cars does not pay dividends from previous

years, only in the year that dividends are declared. So, they will pay 21% of $550,000 ,

which is $115,500 ($550,000 x 0.21).

4.

Identify the declaration date, record date, or payment date associated with

dividends.

Declaration Date: The general date when a company publicly states that it will be paying

dividends to its stockholders some time in the future. This requires an accounting entry.

Record Date: The specific point in time in which companies pay dividends. The record date

must be identified specifically (date, time, second) because stocks are so often sold and

bought several times in a day. Therefore, the company must find out to whom they are

paying dividends. Are they paying to Phil Knight, or to investor Mark Parker who bought his

stock two minutes ago? This requires no accounting entry, just serves as an indicator to the

company about WHERE to send their dividend payments.

Payment Date: The point in time in which companies send out their dividend payments. This

requires an accounting entry.

5. Identify the journal entry to record the declaration of a dividend.

Remember: The declaration of dividends is just the declaration by the company publicly

saying they will pay dividends, at some point in the future.

Example 1: Simple Truth Organic Company declares $600,000 of dividends on August 20,

2028.

We debit Cash Dividends [ because Dividends have a normal debit balance, remember ;) ? ],

and credit Dividends Payable as a liability because we still have not sent out payments.

August 20, 2028

6.

Cash Dividends

Dividends Payable

$600,000

$600,000

Define retained earnings.

Retained Earnings: Accumulated amount of cash (or Net Income) that companies save for

future use.

7.

Calculate various components of the stockholders’ equity section of the

balance sheet. !!!

Company Name

Balance Sheet (partial)

December 31, 2028

★ STOCKHOLDERS EQUITY

Paid-In Capital

Capital Stock

Preferred Stock

+ Common Stock

---------------------

Total Capital Stock

+

Additional Paid-In Capital

Paid-In Excess of Par Value-Preferred Stock

Paid-In Excess of Stated Value-Common Stock

------------------------------------------------------------+ Total Additional Paid-In Capital

-------------------------------------------Total Paid-In Capital

+ Retained Earnings

------------------------------------------

Total Paid-In Capital and Retained Earnings

+ Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income

- Treasury Stock

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------★ TOTAL STOCKHOLDERS EQUITY ★

CHP 12

1. Identify the purpose of the Statement of Cash Flows.

The Statement of Cash Flows measures:

- A company’s ability to generate future cash flows, pay dividends and pay debt

- The reasons why there is a difference between Net Income and Net Cash

Provided/Used By Operating Activities

- Cash investing and financing transactions during the period

2. Distinguish among operating, investing, and financing activities.

As a company, you have to do certain activities in order to keep business running. These

activities often result in a movement of cash, so the Statement of Cash Flows ensures that

these activities and the cash moving with them are tracked.

We will have to categorize business activities as either: Operating, Investing or Financing.

Financing Activities deal with raising money for the company, or paying that money

back.

Examples:

- Issuing common stock for cash

- Declaring dividends

- Retirement of bonds

Investing Activities deal with buying and selling Long Term Assets, including

investments.

Examples:

- Selling company property (land, buildings, equipment, etc)

- Buying company property (land, buildings, equipment, etc)

- Selling an investment for cash

Operating Activities deal with everything else that's not investing or financing. This

often includes changes to Income Statement accounts.

Examples:

- Paying suppliers and creditors

- Gaining revenue from sales of goods and services

- Incurring expenses to continue operation (ex: Salaries and Wages Expense)

3. Identify the relationship between cash flows and life cycle phases.

At the beginning of its life, a company will

have high financing activities as a means

to raise money. Operations and

Investments will be minimal.

At maturity, all three types of activities will

most likely be close to or equal in

magnitude in relation to one another.

- Figure 12.15 Kimmel, Paul D., Jerry Weygandt,

Donald Kieso. Accounting: Tools for BusinessDecision Making,

7th Edition. Wiley, 2019. VitalBook file.

Similar to a human life, companies also go

through cycle phases: Introductory,

Growth, Maturity and Decline.

At its decline, a company will have low

financing activities, while operating and

investment activities will start to slowly

decline.

4.

Using the indirect method, calculate net cash provided (used) by operating

activities.

Why Do We Need This?: ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------One important concept to remember on the final:

The Statement of Cash Flows operates under the Cash Basis of Accounting, which is

quite contradictory to most of what we have learned in this semester. If you recall,

Accrual Basis Accounting recognizes revenue and expenses as a result from the passage of

time. For example, Interest Payable is a liability that increases over time even though no

cash is being given or received. Without recording, expenses are understated and net

income is overstated.

In other words, the Statement of Cash Flows does not take into account a lot of our

adjusting entries because it operates under Cash Basis Accounting. So, we must adjust our

Cash Flows to add back these current liabilities, and decrease these current assets. This will

adjust our Net Income into something called Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities.

For example, Interest Payable would be added back to our Net Income because we no

longer wish to account for expenses accrued over time. We only want to account for

revenues received in cash and expenses paid in cash (no accruals or deferrals!).

End of Explanation:------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------If you are still confused (I wouldn’t blame you), I have a complete explanation of how

Deferrals and Accruals work on my Midterm 1 Study Guide (Chp 4, #2, #3, and #4).

It doesn’t hurt to review, as all of these concepts will be covered on the final exam!

If you have any questions, feel free to contact me (720) 202 7262! :)

So, how exactly do we do this?

We must decide whether we need to add or subtract an account to our Net Income, given

certain Operating activities (such as the examples given on Chp 12, #2). First, I will provide a

reference table containing all the rules, and then I will run through several examples:

Type of Operating Activity

Account Involved

Do We +/- to Net Income?

Non-Cash Changes

Depreciation Expense

Amortization Expense

Add

Add

Gains & Losses

Loss in Disposal of Asset

Gain on Disposal of Asset

Add

Subtract

Changes in Current Assets

and Current Liabilities

Increase in Current Asset

Decrease in Current Asset

Increase in Current Liability

Decrease in Current Liability

Subtract

Add

Add

Subtract

When Net Income is positive after adjustments, we label the account

“Net Cash PROVIDED BY Operating Activities”

When Net Income is negative after adjustments, we label the account

“Net Cash USED BY Operating Activities”

Example 1:

Cleopatra Company had a Net Income of $45,000 on December 31, 2014. It also had a

Depreciation Expense of $13,450 and Amortization Expense of $15,000.

What is the Net Cash Provided (or used) by Operating Activities after these adjustments?

Phew... Okay, we got this:

We are given a Net Income of $45,000 to start with. According to our table, Depreciation

Expense and Amortization Expense must be added to our Net Income.

Original Net Income ($45,000)

+ Depreciation Expense ($13,450)

+ Amortization Expense ($15,000)

= Net Cash PROVIDED BY Operating Activities ($73,450)

Wait! Why are we adding Expenses? Aren’t Expenses supposed to Decrease Net

Income??

Under Accrual Basis Accounting, you would be correct. But remember, the Statement of

Cash Flows is the weird cousin in the family, because it follows Cash Basis Accounting.

Cash Basis Accounting only cares about cash being given and received.

This means that DEFERRALS AND ACCRUALS must be added and subtracted back to Net

Income, respectively.

Alright let’s keep going!

Example 2:

King Tut Company had a Net Income of $250,000 on December 31, 2015. It also had a Loss

on Disposal of Plant Assets of $84,000 and Gain on Disposal of Plant Assets of $160,000.

What is the Net Cash Provided (or used) by Operating Activities after these adjustments?

We are given a Net Income of $250,000 to start with. According to our table,

Loss on Disposal of Plant Assets must be added,

while Gain on Disposal of Plant Assets must be subtracted from our Net Income

Original Net Income ($250,000)

+ Loss on Disposal of Plant Assets ($84,000)

- Gain on Disposal of Plant Assets (-$360,000)

= Net Cash USED BY Operating Activities (- $26,000)

(If you are still a bit confused, I have a full explanation of how Loss and Gains on

Disposals of Plant Assets work on my Midterm 2 Study Guide Chp9 #7).

Example 3:

Ramses II Company had a Net Income of $380,000 on December 21, 2016. It also had:

An increase on Interest Receivables for $123,750

A decrease on Prepaid Insurance for $20,940

An increase in Interest Payable for $67,000

A decrease in Salaries and Wages Payable for $213,450

What is the Net Cash Provided (or used) by Operating Activities after these adjustments?

We are given a Net Income of $380,000 to start. According to our table:

Interest Receivables is a CURRENT ASSET and is increased, so we must subtract this.

Prepaid Insurance is a CURRENT ASSET and is decreased, so we must add this.

Interest Payable is a CURRENT LIABILITY and is increased, so we must add this.

Salaries and Wages Payable is CURRENT LIABILITY and is decreased, so we must

subtract this.

Original Net Income ($380,000)

- Interest Receivables ($123,750)

+ Prepaid Insurance ($20,940)

+ Interest Payable ($67,000)

- Salaries and Wages Payable ($213,450)

= Net Cash PROVIDED BY Operating Activities ($130,740)

Need more practice? WileyPlus Chp 12 #5-6 has more practice for these types of questions!

5. Calculate net cash provided (used) by investing activities.

So, how exactly do we do this?

We must decide whether we need to add or subtract an account to our Net Income, given

certain Investing activities (such as the examples given on Chp 12, #2). First, I will provide a

reference table containing all the rules, and then I will run through several examples:

Type of Investing Activity

Do We +/- to Net Income?

Sale of PPE

(Property, Plant, Equipment)

ADD

(since Cash is received/ADDED to

company savings to purchase PPE)

Purchase of PPE

(Property, Plant, Equipment)

SUBTRACT

(since Cash is given/SUBTRACTED from

company savings to purchase PPE)

When Net Income is positive after adjustments, we label the account

“Net Cash PROVIDED BY Investing Activities”

When Net Income is negative after adjustments, we label the account

“Net Cash USED BY Investing Activities”

Example 1: Galvarino Company had a Net Income of $154,800 on December 31, 2019. It

also sold Equipment for $54,600 and purchased a building for $500,000. What is the Net

Cash Provided (or used) by Investing Activities after these adjustments?

According to our table, Sale of Equipment must be added and Purchase of Building must be

subtracted.

Original Net Income ($154,800)

+ Sale of Equipment ($54,600)

- Purchase of Building ($500,000)

= Net Cash USED BY Investing Activities (- $290,600)

6. Calculate net cash provided (used) by financing activities.

So, how exactly do we do this?

We must decide whether we need to add or subtract an account to our Net Income, given

certain Investing activities (such as the examples given on Chp 12, #2). First, I will provide a

reference table containing all the rules, and then I will run through several examples:

Type of Financing Activity

Do We +/- to Net Income?

Payment of Dividends

SUBTRACT

(since Cash is given/SUBTRACTED from

company savings to pay dividends)

Issuance of Common Stock

ADD

(since Cash is received/ADDED to

company savings when stock is issued)

Purchase of Treasury Stock/Bonds

SUBTRACT

(since Cash is given/SUBTRACTED from

company savings to purchase treasury

stocks/bonds)

When Net Income is positive after adjustments, we label the account

“Net Cash PROVIDED BY Financing Activities”

When Net Income is negative after adjustments, we label the account

“Net Cash USED BY Financing Activities”

Example 1:

Blue Bird Inc. had a Net Income of $408,700 on December 31, 2020. It also had a Payment

of Dividends for $103,500, Issuance of Common Stock for $150,040, and Purchase of

Treasury Stock for $201,000. What is the Net Cash Provided (or used) by Financing

Activities after these adjustments?

We are given a Net Income of $408,700 to start with. According to our table,

Payment of Dividends must be subtracted

Issuance of Common Stock must be added

Purchase of Treasury Stock must be subtracted.

Original Net Income ($408,700)

- Payment of Dividends ($103,500)

+ Issuance of Common Stock($150,040)

- Purchase of Treasury Stock ($201,000)

= Net Cash PROVIDED BY Financing Activities ($254,240)

If you are still a bit confused, I have a full explanation on the effect of Common Stock and

Dividends on financial accounts in this study guide CHP 11 #2 and #5 :)

7. Calculate free cash flow

Free Cash Flow

= Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities - Capital Expenditures - Cash Dividends

Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities and Cash Dividends will be explicitly given

from a Statement of Cash Flows, but Capital Expenditures takes a little bit of thinking.

Capital Expenditures is the amount of money spent to replace long term assets as

they wear out. In other words, it is the amount of money used to purchase, renovate or

replace PPE (Property, Plant, and Equipment). Within the Statement of Cash Flows, you

have to look for the number associated with “Expenditures on Property, Plant or Equipment”.

Sometimes it is not listed as such, and you have to look for “Purchase of Equipment”,

“Purchase of Property”, and/or “Purchase of Plant/Land”.