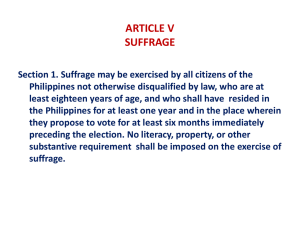

Source: http://asiafoundation.org/in-asia/2012/03/07/early-feminism-in-the-philippines/ Early Feminism in the Philippines March 7, 2012 By Athena Lydia Casambre and Steven Rood The Philippines has been noted as having one of the smallest gender disparities in the world. The gender gap has been closed in both health and education; the country has had two female presidents (Corazon Aquino from 19861992 and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo from 2001-2010); and had its first woman Supreme Court justice ( Cecilia Muñoz Palma in 1973) before the United States had one (Sandra Day O’Connor in 1981). These achievements reflect a long history of efforts by women to involve themselves equally in governance as well as in society. The struggle for women’s right to vote was the site for early feminism in the Philippines. It spanned three decades, culminating in September 1937 with the ratification by the Commonwealth government National Assembly after a plebiscite vote by women voters on April 30, 1937. With 447,725 “Yes” votes, a number well above the 300,000 quota stipulated by the 1935 Constitution, finally “the Filipina got the vote.” Writer, feminist activist, and beauty queen Pura Villanueva Kalaw wrote and published a pamphlet in 1952 called: “How the Filipina Got the Vote,” summarizing three decades of organization and legislative lobbying by women’s groups, with the support – paradoxically – of men in positions of power. The women’s organizations primarily responsible for suffrage mobilization had begun as socio-civic organizations early in the 20th century. The Asociacion Femenista Filipina organized in July 1905 under the leadership of Dona Concepcion Felix (later married to Felipe Calderon), and shortly after, Pura Villanueva (later married to Teodoro M. Kalaw) responded to the call to organize women nationwide by organizing the Asociacion Femenista Ilonga. The objectives of the organization at that time were limited to social concerns such as prison reform, improvement of education, and “prevention of individual immorality.” As gleaned from Purita Villanueva’s early writings published in El Tiempo (a major newspaper in Iloilo), this social activism was rooted in the concept of women as precisely positioned in the domestic sphere as shapers of moral sentiments of the young in their care first of all, as well as influencing their husbands and other family relations. Education to keep abreast of the times and to hone rationality were considered important for women to be able to fulfill this role. A visit to Manila in 1912 by two suffragettes, Dr. Aletta Jacobs from Holland and Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt from the United States, turned the focus of women’s organization to suffrage. The meeting of Filipino women leaders with the foreign visitors resulted in the organization of the Society for the Advancement of Women (later changed to Women’s Club of Manila). During World War I, the Women’s Club of Manila helped government efforts by participating in the sale of Liberty Bonds and fundraising for the Red Cross. The endorsement of woman suffrage to the Philippine legislative assembly by three successive American governorsgeneral was a major factor in the push to woman suffrage, although such high level endorsements were no guarantee of easy success. Governors-General Francis B. Harrison, Leonard Wood, and Frank B. Murphy endorsed woman suffrage to assemblies between 1918 and 1933; the Senate approved the bill initially in 1919, but it took 26 years from the first bill presented by Congressman Sotto at the First Philippine Assembly in 1907, through several defeats, until Gov. Gen. Frank Murphy affixed his signature to a woman suffrage bill in December 1933. Throughout this period of legislative struggle, women continued to organize and mobilize support: the Women’s Club of Manila organized the National Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1921, the Liga Nacional de Damas Filipinas was organized in 1922, and the Women’s Citizens League in 1928. However, the 1935 Constitution presented yet another hurdle for woman suffrage. The provision on suffrage stipulated that the right of suffrage shall be extended to women if “not less than three hundred thousand women” vote affirmatively in a plebiscite. Women’s organizations did not back down from the challenge, and mobilized to get more women registered and to actually come out on voting day. The campaign featured a multilingual radio campaign on the eve of the plebiscite by women leaders Judge Natividad Almeda Lopez (Spanish), Josefa Jara Martinez (Ilongo), Pilar Hidalgo Lim (English), Concepcion Felix Rodriguez (Tagalog), Geronima T. Pecson (Pangasinan), Corazon Torres (Cebuano), and Josefa Llanes Escoda (Ilocano). Twenty-nine percent of eligible women voters registered to vote from April 10-17, 1937; of these, about 86 percent eventually voted on April 30, 1937. Filipinas voted 10 to 1 in the affirmative, handing a victory to the suffragists that exceeded the constitutional quota. Thus, the women got the vote. Notwithstanding this early victory, and the generally small gender disparity in the Philippines, it is in the category of “political empowerment” that the country fares less well – 16th in the world (instead of in the top 10 in other categories). Combine this with the fact that many women become officials due to their membership in political clans and it’s evident that considerable distance remains to achieve full empowerment of women. But, there’s no doubt that this distance will be far shorter, thanks to the progress forged by Filipinas in the first half of the 20th century. This is the seventh posting in the series, “A Representative Professor,” a weekly series during a teaching sabbatical at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Steven Rood is The Asia Foundation’s country representative in the Philippines. He can be reached at srood@asiafound.org. Athena Lydia Casambre recently retired as professor of Political Science at the University of the Philippines. She can be reached at alcc@up.edu.ph. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the individual authors and not those of The Asia Foundation.