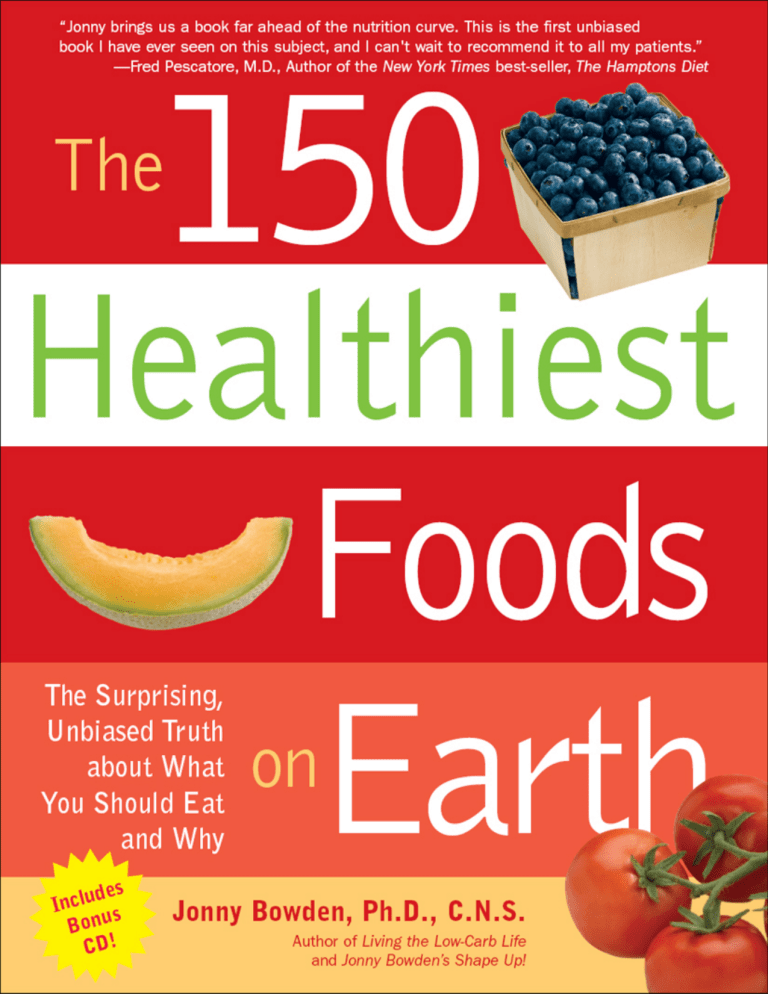

150 Healthiest Foods: Nutrition Guide for Optimal Health

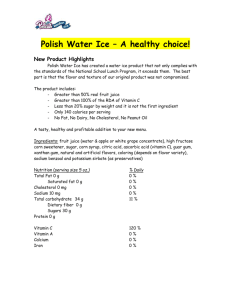

advertisement