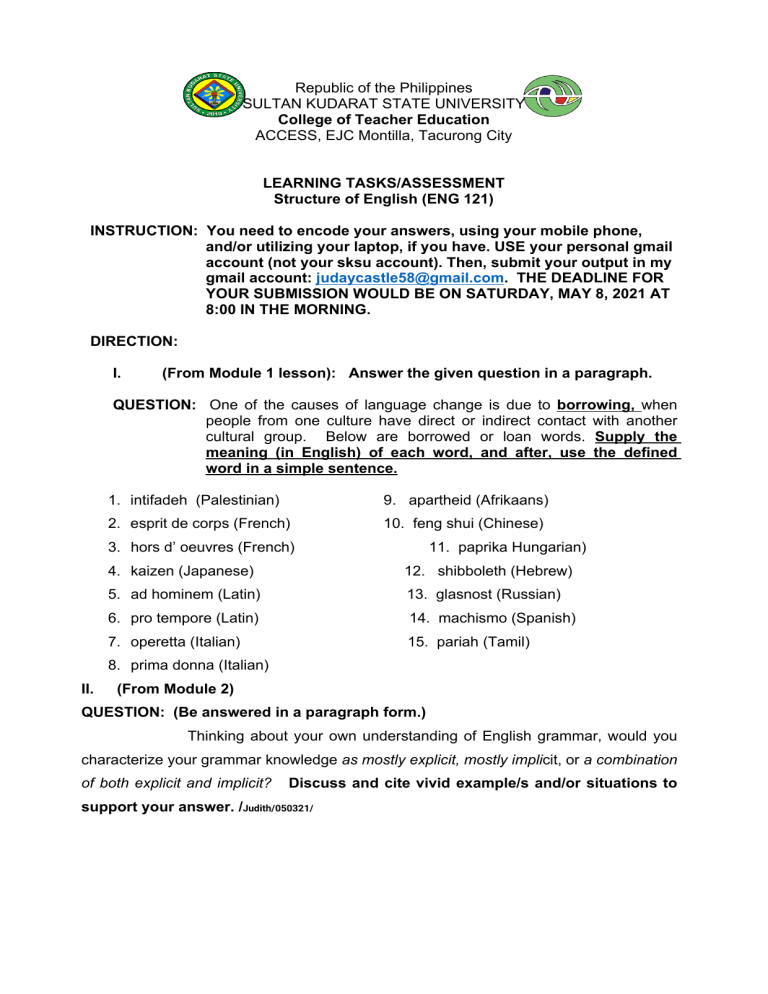

Structure of English: Language Change & Grammar Assessment

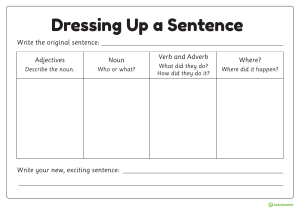

advertisement