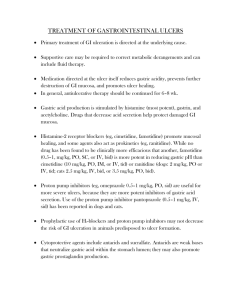

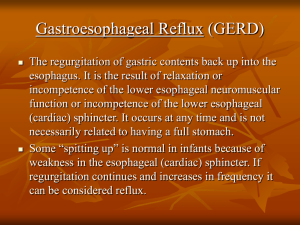

MEDICAL-SURGICAL ACHALASIA ACHALASIA i. About the disease ii. Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis iii. Clinical Presentation (Signs/Symptoms) iv. Assessment/Diagnostic Findings v. Classifications vi. Complications vii. Treatment/Management ABOUT THE DISEASE Achalasia is absent or ineffective peristalsis of the distal esophagus accompanied by failure of the esophageal sphincter to relax in response to swallowing. Deglutition (swallowing) initiates a peristaltic wave down the esophagus and also triggers the relaxation of the LES (lower esophageal sphincter) allowing food to enter the stomach. Achalasia is Greek for “does not relax” Patients primarily present with regurgitation and dysphagia Epidemiology: Affects males and females equally Presents ages 25-60 progress slowly and occurs most often in people 40 years or older CLINICAL PRESENTATION The main symptom is dysphagia (solids and liquids). May also report non-cardiac chest or epigastric pain Pyrosis (heartburn) that may or may not be associated with eating Secondary pulmonary complications may result from aspiration of gastric contents Regurgitation (spitting food without force) Difficult belching (expelling excess air from upper digestive tract) Chest pain (angina) Heartburn +/- weight loss (mild only) ASSESSMENT/DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS Loss of ganglion cells within the myenteric (Auerbach's) plexus (longer the disease the fewer ganglion cells present) Loss of inhibitory (NO) ganglion function resulting in impaired relaxation. Intact cholinergic (excitatory) Use of CXR (chest radiograph) Result: Widened mediastinum and absence of gastric bubble shows esophageal dilation above the narrowing at the gastroesophageal junction CCK (cholecystokonin) octapeptide test Possible autoimmune disease(viral insult) involving latent HSV-1 Likely genetic component Allgrove Syndrome(AAA): rare autosomal recessive disorder associated with AchalasiaAddisonianism-Alacrimia Manometry (confirmatory test) Barium swallow (primary screening) CLASSIFICATIONS *BIRD-LIKE BEAK APPEARANCE Type I: Classic achalasia Type II: Achalasia with compartmentalized panesophageal pressurization (>30mmHg) Type III: Achalasia with spastic contractions (with or without compartmentalized pressurization) *Type II and III=“vigorous achalasia” Historical correlation: Chest pain more prevalent with Type II and III EGD (Esophagogastroduodenoscopy) Recommended in all achalasia patients to rule out malignancy or “pseudoachalasia” (excessive weight loss loss, symptoms < 6mos, >60 years old) Examine cardia of stomach well for malignancy Dilated esophagus with retained food Esophageal stasis predisposes to candida esophagitis Type I- Heller myotomy Type II- good response to all therapy Type III- poor response to all therapy *Felt that Type I represents progression from Type II Esophageal decompensation after prolonged outlet obstruction and continued destruction of myenteric plexus Treat early to try to prevent progression to Type I COMPLICATIONS Aspiration PNA (pneumonia) Epiphrenic diverticulum In standard manometry, Elevated LES pressure (usually >45mmHg) Incomplete LES relaxation (normal <8mmHg) Aperistalsis (there can still be contractions) SCC (squamous cell carcinoma) > Adenocarcinoma 16 fold increase Presents approximately 15 years after diagnosis of achalasia TREATMENTS *The patient is instructed to eat slowly and to drink fluids with meals. VIGOROUS Achalasia: most contractions in Achalasia are low amplitude but some patient’s have highamplitude contractions (3760mmHg) Nitrates and CCB (Nifedipine); relaxes the smooth muscle Used for patient’s unwilling or unable to undergo more invasive therapy Variable success If standard manometry has 3-8 sensors at 3-5 cm apart, HIGH RESOLUTION MANOMETRY has 36 sensors at 1 cm apart Medical Therapy Botulinum Toxin Injected into LES (25units in 4 quadrants) Poisons the excitatory (acetylcholine) neurons Success rates of 80% however relief wanes gradually to 41% at 12 mos. Requires repeat injections Increases intraoperative perforation and myotomy failure Presence of low LES pressure or dilated esophagus predicted higher rate of failure with Heller High cost, longer recovery, GERD Complication rate is higher if surgical myotomy performed after endoscopic therapy Pneumatic dilation and Heller are comparable Dilation 1. Bougie Temporary relief but lower risk of perforation 2. Pneumatic Forceful dilation, tears muscle fibers Stepwise approach: 3.0cm >3.5cm ->4.0cm High success rate (85%) 1.6% perforation rate Gradual waning of success rate with repeat dilations Consider additional therapy for persistent dysphagia after 2-3 dilations Consider PPI therapy The procedure can be painful; therefore, moderate sedation in the form of an analgesic or tranquilizer, or both, is given for the treatment Surgical Myotomy (Heller and Open myotomy) LES is cut Often partial wrap (Dor or Toupet fundoplication) to prevent reflux (No nissen, worse dysphagia) High success rates (Open, 70%-85% at 10 years and 65-73% at 20-30 yrs) and low recurrence TREATMENT ALGORITHM MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GERD) GERD i. ii. iii. iv. v. vi. vii. viii. About the disease Epidemiology Risk factors Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis Clinical Presentation (Signs/Symptoms) Assessment/Diagnostic Findings Complications Treatment/Management Incidence in similar between men and women About 50% of pregnant women will experience GERD; can also occur in infants *Pregnancy causes enlargement of uterus which causes changes in the LES through stomach uplift RISK FACTORS ABOUT THE DISEASE A fairly common disorder marked by backflow of gastric or duodenal contents into the esophagus that causes troublesome symptoms and/or mucosal injury to the esophagus. Pyrosis frequency of more than 2 times per week is sometimes used as a criteria for GERD Hydrochloric acid (which are produced by parietal cells) has a pH level of or less than 4 which damages the lumen of the stomach Differential diagnosis of GERD chest pain: acute myocardial infarction Smoking Excessive caffeine intake Episodic pyrosis (heartburn) that is not frequent enough or painful enough to be considered bothersome by the patient is not included in the above consensus GERD definition Alcohol use A condition that occurs when refluxed stomach contents lead to troublesome symptoms and/or complications Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) Fitting clothes Respiratory diseases gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS Excessive reflux may occur because of an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter, pyloric stenosis, hiatal hernia, or a motility disorder. Symptoms of GERD vary in severity, duration, and frequency. Key Factors in the Development of GERD When the esophagus is repeatedly exposed to refluxed material for prolonged periods of time, inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis) occurs, and in some cases it can progress to erosion of the squamous epithelium of the esophagus (erosive esophagitis) and may lead to other complications. EPIDEMIOLOGY A decrease in lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure Decreased clearance of gastric contents from the esophagus Decreased mucosal resistance in the esophagus Composition of reflux contents “extra acidic” The incidence of GERD seems to increase with aging and is seen in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and obstructive airway disorders (asthma, COPD, cystic fibrosis) Heartburn is the most frequent clinical complaint Most frequently occurs in adults over 40 years of age Gastric fluid that has a pH < 4 is extremely caustic to the esophageal mucosa. Decreased gastric emptying (increased gastric emptying time) Certain anatomic features Most commonly a hiatal hernia THIRD CATEGORY: EXTRASOPHAGEAL/ATYPICAL CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Symptoms may include: pyrosis (heartburn, specifically more commonly described as a burning sensation in the esophagus) dyspepsia (indigestion) regurgitation These symptoms have an association with GERD but causality should only be considered if a concomitant esophageal symptoms are present: Chronic cough Asthma-like symptoms About 50% of those with asthma have GERD dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) or odynophagia (painful swallowing) Laryngitis/Hoarseness Recurrent sore throat Dental enamel erosion hypersalivation esophagitis *concomitant – associated to or of; occurring *Symptoms may mimic those of a heart attack. *Angina present in GERD may have a differential diagnosis as in acute myocardial infarction Aggravating Factors (makes condition worse): o Recumbency (leaning, resting, or reclining) o Increased intra-abdominal pressure 1. Typical or “CLASSIC” symptoms o Reduced gastric motility 2. ALARM (Complicated) symptoms o Decreased LES tone or pressure 3. EXTRASOPHAGEAL (ATYPICAL) symptoms o Direct mucosal irritation GERD symptoms are grouped in three categories: FIRST CATEGORY: TYPICAL OR CLASSIC at the same time Pyrosis (heartburn) * Hallmark symptom *A substernal feeling of warmth or burning rising up from the abdomen that may radiate to the neck Foods that decrease LES pressure fatty foods peppermint spearmint chocolate coffee cola tea garlic onions chili peppers Regurgitation/Belching Medications that decrease LES pressure Acid brash/hypersalivation Chest pain (non-cardiac in nature) SECOND CATEGORY: ALARM SYMPTOMS *Any of these symptoms warrant immediate referral for testing: Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) Odynophagia (painful swallowing) Bleeding Unexplained weight loss Choking (hand across the neck) Chest pain (if could be cardiac in nature) anticholinergics barbiturates benzodiazepines caffeine dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers dopamine estrogen ethanol narcotics nicotine nitrates progesterone theophylline Foods that are direct irritants to the esophageal mucosa Spicy foods orange juice tomato juice coffee Medications that are direct irritants to esophageal mucosa Oral bisphosphonates Aspirin Iron NSAIDs Quinidine potassium ASSESSMENT/DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS CLINICAL HISTORY *The patient’s history aids in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. *Patients presenting with extraesophageal or atypical symptoms should be reviewed on a case-by-case basis to be considered for testing *Alarm symptoms always warrant further testing *Patient’s description of typical or classic GERD symptoms such as pyrosis, is often enough to consider GERD as an initial diagnosis ENDOSCOPY Endoscopy is the technique of choice to identify complications of GERD such as ulcerations, erosions, Barrett’s esophagus, etc. Biopsy of the esophageal tissue is needed to identify and diagnose Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma Many patients with GERD (presenting with typical or atypical symptoms) will have normal appearing esophageal mucosa on endoscopy Usually not part of the work-up except in certain subsets of patients (alarm symptoms, those refractory to treatment, etc.) BARIUM SWALLOW/RADIOGRAPHY Evaluates damage to the esophageal mucosa Not routinely used to diagnose GERD due to a lack of sensitivity and specificity Can detect hiatal hernia COMPLICATIONS GERD can result in: dental erosion ulcerations in the pharynx and esophagus laryngeal damage esophageal strictures adenocarcinoma pulmonary complications BARRET’S ESOPHAGUS Barrett’s esophagus occurs when the normal squamous cell epithelium in the esophagus converts to a columnar cell epithelium (intestinal-type epithelium) More common in men than women Barrett’s esophagus does not cause specific symptoms but the reflux does Those with Barrett’s esophagus develop adenocarcinoma of the esophagus at a rate of 0.12% per year Gender ratio for esophageal adenocarcinoma is 8:1 (male:female) Patients must be monitored via endoscopy to evaluate changes in cell type and conversion to adenocarcinoma BE is a condition in which the lining of the esophageal mucosa is altered. AMBULATORY pH MONITORING (12-36 HOURS) Used to evaluate the degree of acid reflux Esophageal pH monitoring was historically an uncomfortable procedure, but the advent of wireless capsule pH monitoring is better tolerated and quite accurate. Identifies patients with excessive esophageal acid exposure and helps determine if symptoms are acid related Useful in patients not responding to acid-suppression therapy TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT The initial treatment used is determined by the patient’s condition: Frequency of symptoms Degree of symptoms Presence and/or degree of esophagitis Presence of complications Goals of Treatment: ANTACIDS Alleviate or eliminate acute symptoms Decrease frequency of recurrence Promote healing if esophageal tissue injury is present Prevent complications Mode of action: Neutralizes hydrochloric acid in the stomach, which results in an increase in gastric pH Agents: 1. Magnesium hydroxide 2. Aluminum hydroxide NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES 3. Calcium carbonate Lifestyle modifications Should be incorporated into the management of GERD regardless of the severity of disease Monitoring: Lifestyle modifications should be tailored to an each individual patient’s needs Periodic calcium and phosphate levels if on chronic antacid therapy Anti-reflux surgery Patient interventions: Used as a last resort option in select patients When long-term pharmacologic therapy is undesirable Antacids can decrease the levels of numerous other drugs including tetracycline, digoxin, iron supplements, fluoroquinolones, and ketoconazole. Patients should separate antacids and other medications by at least 2 hours Patients with renal impairment should not use aluminum or magnesium containing antacids unless directed by their physician Onset of relief is less than 5 minutes and duration of relief is 20 to 30 minutes Who have refractory GERD Have complications Endoscopic therapies Results have been disappointing and hence are not usually recommended LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS Weight loss (if the patient is overweight or obese) Elevation of the head of the bed 6 to 8 inches or 30 degrees ANTACIDS-ALGINIC ACID COMBINATION Eat smaller, more frequent meals (as opposed to larger meals less frequently) Mode of action: Include protein-rich meals in diet (increases LES pressure) The antacid neutralizes stomach acid and the alginic acid is a foaming agent that creates a viscous solution that floats on top of the stomach contents and may be protect the esophagus from refluxed stomach acid. Avoid eating 2-3 hours prior to sleeping or lying down Avoid foods or medications that exacerbate GERD Agents: Avoid alcohol 1. Aluminum hydroxide Tobacco cessation 2. Magnesium carbonate The patient is instructed to eat a low-fat diet 3. Alginic acid (Gaviscon) PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENTS Antacids and alginic acid products H2-RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS H2-receptor antagonists (HRA) Mode of action: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) Competitive inhibition of histamine at H2 receptors of gastric parietal cells which inhibits gastric acid secretion Promotility agents . Agents: Common adverse effects: headache 1. Cimetidine (Tagamet) dizziness 2. Famotidine (Pepcid) somnolence 3. Nizatidine (Axid) diarrhea 4. Ranitidine (Zantac) constipation flatulence abdominal pain nausea (Possible) Adverse effects: headache somnolence (drowsiness) fatigue dizziness Increased risk of Clostridium difficile infections constipation Increase risk of community-acquired pneumonia diarrhea Serious side effects: Long-term adverse effects: Monitoring: Monitor for CNS effects (rare) in those over 50 years old or in those with renal or hepatic impairment. Patient interventions: Hypomagnesemia Bone fractures Vitamin B12 deficiency Monitoring: If taking once a day, it is preferable to take the dose at bedtime. Appearance of diarrhea (frequency and type of diarrhea episodes) Onset of relief is 30 to 45 minutes and duration of relief is 4 to 10 hours. Periodic magnesium levels (if long-term therapy) Routine bone density studies (DXA scans) PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS (PPI) *If other risk factors for osteoporosis or bone fractures present Mode of action: Blocks acid secretion by inhibiting gastric H+/K+ adenosine triphosphates found on the secretory surface of gastric parietal cells Results in a long-lasting anti-secretory effect that can maintain gastric pH levels above 4 Agents: Patient interventions: Preferable to take a PPI 30 to 60 minutes before a meal (mainly breakfast) If a second dose is needed, take prior to the evening meal Onset of relief is 2 to 3 hours and the duration of relief is 12 to 24 hours 1. Dexlansoprazole (Dexilant) *most effective 2. Esomeprazole (Nexium) PROMOTILITY AGENTS 3. Lansoprazole (Prevacid) Promotility agents, such as metoclopramide and bethanechol, have been used as adjunct therapy to acid suppression agents such as PPIs in patients who have a known motility defect. However, they are not generally recommended to be used for GERD treatment due to their limited effectiveness and undesirable adverse effect profiles. 4. Omeprazole (Prilosec) 5. Omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate (Zegerid) 6. Pantoprazole (Protonix) *used to avoid interactions with other drugs 7. Rabeprazole (Aciphex) PPIs V. H2-RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS Symptomatic improvement as well as endoscopic healing rates are higher for the PPIs compared to the H2-receptor antagonists. PPIs are therefore preferred over H2-receptor antagonists in patients with erosive disease, moderate to severe symptoms, or with complications. PPIs in Children greater than 1 year of age 15mg per day is recommended for children weighing < 30kg 30mg per day is recommended for children weighing > 30kg MAINTENANCE THERAPY Q: What patients should receive maintenance therapy? o Those with a history of complications (e.g. Barrett’s esophagus, strictures, hemorrhage, ulcerations, etc.) Long-term maintenance therapy with PPIs at the lowest possible dose If NERD/uncomplicated GERD, try to manage with on-demand or intermittent PPI therapy or H2-receptor antagonists Esomeprazole Dosed 10 to 20mg a day for children 1 to 11 years old Dosed at 20 to 40mg a day for children 12 to 17 years old *Can consider intermittent or on demand PPI therapy in some circumstances o Those with symptomatic relapse following discontinuation of the drug or a decrease in dose. Lansoprazole Omeprazole 5mg daily in children weighing between 5 and 10kg 10mg daily in children weighing between 10 and 20kg 20mg daily in children weighing ≥ 20kg ELDERLY PATIENTS PATIENTS WITH EXTRAESOPHAGEAL (ATYPICAL) GERD Patients with atypical symptoms may need higher doses of acid suppression therapy with longer treatment duration compared to those patients with typical symptoms. A PPI trial is recommended to treat extraesophageal symptoms in patients who have typical GERD symptoms as well Reflux monitoring should be considered before a PPI trial in patients with extraesophageal symptoms who do not have typical GERD symptoms. 1. Many elderly patients have decreased defense mechanisms such as decreased saliva production 2. PPI therapy may be warranted for those > 60 years of age with symptomatic GERD 3. They have superior efficacy and have once a day dosing 4. Long-term risk of bone fractures is a concern and elderly patients should be monitored appropriately 5. Elderly are at higher risk of being sensitive to possible CNS effects of H2-receptor antagonists PEDIATRIC PATIENTS 1. A suspected cause of reflux in infants is a developmentally immature LES PATIENTS WITH REFRACTORY GERD 2. Many infants have reflux with little or no clinical consequence 1. Refractory GERD should be considered in patients who have not responded to a standard course of twice a day PPI therapy 3. This uncomplicated reflux usually manifests as regurgitation or spitting up 2. The majority of patients with refractory symptoms experience nocturnal acid breakthrough 4. Usually responds to supportive therapy 3. Switching to a different PPI may be effective in some patients 5. Chronic vomiting associated with GERD must be carefully evaluated and distinguished from other causes. 6. Careful consideration should be given before a medication is recommended 7. When a medication is deemed necessary, ranitidine dosed at 2 to 4mg/kg twice a day is often used 8. PPIs are increasing being used in children older than 1 year 9. Lansoprazole, esomeprazole, and omeprazole are indicated for treating symptomatic and erosive GERD in children greater than 1 year old 10. Omeprazole has been used off-label in children less than 1 year old at a dose of 1mg/kg/day. 4. Adding an H2-receptor antagonist at bedtime for nocturnal symptoms is reasonable but the effect may decrease over time due to tachyphylaxis with H2-receptor antagonists MEDICAL-SURGICAL HIATAL HERNIA HIATAL HERNIA i. About the disease ii. Epidemiology iii. Risk factors iv. Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis v. Types vi. Clinical Presentation (Signs/Symptoms) vii. Assessment/Diagnostic Findings viii. Complications ix. Treatment/Management x. Gerontologic Considerations Size of hiatus not fixed, narrows with increase in intraabdominal pressure Tear of the phrenoesophageal ligament Phrenoesophageal ligament is a fibrous layer of connective tissue and maintains the LES within the abdominal cavity. ABOUT THE DISEASE Hiatal hernia is a condition where the opening in the diaphragm through which the esophagus passes becomes enlarged, and part of the upper stomach moves up into the lower portion of the thorax. Can be referred as: Diaphragmatic hernia and esophageal hernia *Most common abnormality found on upper GI x-ray A hiatal comprises reflux barrier Reduces LES pressure Reduced esophageal acid clearance Transient LES relaxation particularly at night time episodes TYPES EPIDEMIOLOGY *There are two major types of hiatal hernia. *More common in older adults and in women First type: SLIDING or type I RISK FACTORS Increasing age Stomach slides through hiatal opening in diaphragm when patient is supine, goes back into abdominal cavity when patient is standing upright. Trauma Poor nutrition The upper stomach and the gastroesophageal junction are displaced upward and slide in and out of the thorax. Forced recumbent position Congenital weakness PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS Hiatal hernia can be due to: Structural changes which causes: Weakening of muscles in diaphragm Increased intraabdominal pressure which is caused by: Obesity Pregnancy Heavy lifting Most common type; about 95% of patients with esophageal hiatal hernia have a sliding hernia MEDICAL-SURGICAL HIATAL HERNIA ASSESSMENT/DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS Second type: PARAESOPHAGEAL or ROLLING Esophagogastric junction remains in place, but fundus and greater curvature of stomach roll up through diaphragm Acute paraesophageal hernia is a medical emergency. Occurs when all or part of the stomach pushes through the diaphragm beside the esophagus Paraesophageal hernias are further classified as types II, III, or IV, depending on the extent of herniation. Diagnoses are typically confirmed by: X-ray Barium swallow Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) …which is the passage of a fiber-optic tube through the mouth and throat into the digestive tract for visualization of the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine Type IV has the greatest herniation, with other intraabdominal viscera such as the colon, spleen, or small bowel evidencing displacement into the chest along with the stomach. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Esophageal manometry Chest CT scan Symptoms may include: May be asymptomatic Heartburn or pyrosis (especially after meal or when lying supine) Dysphagia Regurgitation *The patient may present with vague symptoms of intermittent epigastric pain or fullness after eating. *Large hiatal hernias may lead to intolerance to food, nausea, and vomiting. *Sliding hiatal hernias are commonly associated with GERD. *Hemorrhage, obstruction, and strangulation can occur with any type of hernia. MEDICAL-SURGICAL HIATAL HERNIA 3. Prevent movement of gastroesophageal junction COMPLICATIONS If left untreated, hiatal hernia can lead or cause: GERD Esophagitis Hemorrhage from erosion Stenosis (fixed narrowing of the esophagus) Ulcerations of herniated portion Strangulation of the hernia Regurgitation with tracheal aspiration Increased risk of respiratory problems (shortness of breath or chronic cough) o Herniotomy - o Herniorrhaphy - o Excision of hernia sac Closure of hiatal defect Gastropexy - Attachment of stomach subdiaphragmatically to prevent reherniation TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT Includes frequent, small feedings that can pass easily through the esophagus Patient is advised not to recline for 1 hour after eating, to prevent reflux or movement of the hernia, and to elevate the head of the bed on 4- to 8-inch (10to 20-cm) blocks to prevent the hernia from sliding upward o Current guidelines recommend a laparoscopic approach, with an open transabdominal or transthoracic approach reserved for patients with complications such as bleeding, dense adhesions, or injury to the spleen. o Laparoscopically performed Nissen and Toupet techniques are standard anti-reflux surgeries. Lifestyle modifications: Eliminate alcohol Stop smoking Avoid lifting/straining Reduce weight, if necessary Use of anti-secretory agents and antacids as prescribed by physician SURGICAL MANAGEMENT *Surgical hernia repair is indicated in patients who are symptomatic, although the primary reason for the surgery is typically to relieve GERD symptoms and not repair the hernia. * Surgical repair is often reserved for patients with more extreme cases that involve gastric outlet obstruction or suspected gastric strangulation, which may result in ischemia, necrosis, or perforation of the stomach Goals of surgical therapy of hiatal hernia: 1. 2. Reduce hernia Provide acceptable lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure MEDICAL-SURGICAL HIATAL HERNIA o Thoracic or open abdominal approach is used, depending on the individual patient. POST-SURGICAL CONSIDERATIONS *Up to 50% of patients may experience early postoperative dysphagia Advances the diet slowly from liquids to solids Managing nausea and vomiting, tracking nutritional intake, and monitoring weight *Also monitors for postoperative belching, vomiting, gagging, abdominal distension, and epigastric chest pain, which may indicate the need for surgical revision *These should be reported immediately to the primary provider GERONTOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS Higher Incidence with age Medications commonly taken by older patients can decrease LES pressure LES may become less competent with aging First indication may be esophageal bleeding or respiratory complications MEDICAL-SURGICAL NAUSEA AND VOMITING NAUSEA AND VOMITING i. Important notes to follow ii. Epidemiology iii. General approach in managing nausea and vomiting iv. Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis v. Treatment/Management ▪ Aim for acceptable control < 3 days ▪ Consider whether dietary/ other factors may help. ✓ Avoiding triggers IMPORTANT NOTES TO FOLLOW Vomiting post chemo is much better controlled than nausea The evidence for use of anti-emetics is poor ✓ Parenteral fluids ✓ Limiting oral intake, protein meals, low fat diet ✓ Relaxation techniques ✓ Acupuncture point P6 ✓ Ginger ✓ Surgery (stents, venting g-tubes) Intractable nausea and vomiting “Nausea and vomiting that is not adequately controlled after multiple anti-emetics are used in series and/or in combination” Those with the most difficult N&V to manage tend to be those with altered anatomy. Eg. due to malignant bowel obstruction (dysfunction) or stents/surgical interventions PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS EPIDEMIOLOGY Stomach – usually has slow wave contractions (3/min) Rate increases with ‘circular vection’ Vasopressin release Nausea perception related to vasopressin release Primates – VP antagonists stop motion sickness Humans – ginger reduces nausea, vasopressin rise, reduced tachygastria in motion sickness trials GENERAL APPROACH IN MANAGING NAUSEA AND VOMITING 1) Initially - identify and treat reversible causes • This may not be appropriate if someone is imminently dying 2) Assess severity – does the patient need rehydration? 3) Start anti-emetic treatment a. Prescribe regularly TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT b. Review controls every 24-48 hours A second line anti-emetic is required in 1/3 of patients 4) Consider route of administration Oral route maybe ineffective as frequent vomiting means poor absorption Community options: Dietary Management • Protein meal – regulates gastrin release, which reduces gastric dysrhythmia & nausea Gastroparesis diet: • Low fat – fat activates stretch receptors in stomach fluids Rectal route: domperidone suppositories Buccal prochlorperazine Hysoscine patch (granisetron patch) Drugs that help alleviate nausea and vomiting • Maintains nutrition & hydration Metoclopramide Olanzapine orodispersible melt = 5mg strength ▪ Remember N&V is often multi-factorial Prokinetic Dopamine 2 antagonist, 5HT4 agonist, 5HT3 antagonist Central (CTZ) and peripheral action (gut mucosa) MEDICAL-SURGICAL NAUSEA AND VOMITING Prokinetic effect antagonised by anticholinergic drugs Side effects: Extrapyramidal symptoms Drowsiness, restlessness, depression, diarrhea Max 30mg in 24 hours for up to 5 days – EU review 2013) Drowsiness, urinary retention, dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, headache, psychomotor impairment Caution in severe liver disease, severe heart failure, renal failure, glaucoma Notes: ▪ Not advocated for use in heart failure ▪ Increases systemic & pulmonary arterial pressures ▪ Increases right & left ventricular filling pressures ▪ Counteract beneficial hemodynamic effects of opioids in heart failure Domperidone Prokinetic Dopamine 2 antagonist Acts peripherally and at the CTZ Does not readily cross the blood brain barrier Oral only Hyoscine Hydrobromide / Butylbromide Side effects: Rarely extrapyramidal Hyperprolactinaemia Cardiac arrhythmias Max dose 10mg TDS (for up to 7 days) Ondansetron Haloperidol Dopamine 2 antagonist, 5HT2a and α1antagonist Acts predominantly at the CTZ but also peripherally (gut mucosa) First line for biochemical induced N&V T½ 13 – 35 hours Side effects: Extrapyramidal, hyperprolactinaemia Minimal sedation and hypotension NB - Prolongation of QT interval Cyclizine H1 antagonist and cholinergic muscarinic antagonist Acts at the vestibular apparatus (& vomiting centre) Plasma T½ 13 hours Side effects: 5HT3 antagonist Acts at CTZ and gut mucosa Blocks amplifying effect of excess 5HT on vagus Bowel wall enterochromaffin cells release 5HT by various stimuli. Sensitises the vagal afferent nerves to emetogenic substances via 5HT3 receptors Early N&V post chemo: First 24hrs after chemo only Useful where excessive 5HT released eg chemotherapy or radiotherapy induced damage of gut mucosa, bowel distension, renal failure Side effects: Headache Flushing Constipation MEDICAL-SURGICAL NAUSEA AND VOMITING Aprepitant Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (NK1) Substance P found widely in the CNS, including CTZ, VC and GI tract Chemotherapy increases substance P levels as well as serotonin release Antiemetic effects of NK1 antagonism is a central effect Effective for delayed Chemo Induced N&V (>24hrs) Given alongside 5HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone No evidence that it has much role in palliative care Side effects: Drowsiness, weight gain Dry mouth, constipation, hypotension, peripheral edema Less movement disorders than with Haloperidol Dexamethasone Glucocorticoid Reduces permeability of the CTZ and the blood brain barrier to emetogenic substances Reduces neuronal content of GABA in the brain stem Suggested that antagonism of PGs, release of endorphins and depletion of tryptophan may play a role Central or peripheral effect Levomepromazine Dopamine 2 antagonist, Muscarinic cholinergic antagonist, Histamine 1 antagonist, 5HT2A antagonist, alpha-adrenergic antagonist Acts at vomiting centre Plasma T½ 15 – 30 hours Side effects: Sedation, weakness Dry mouth, hypotension, extrapyramidal symptoms Summary Vomiting is unpleasant and debilitating There are multiple causes General measures and drug interventions are usually successful It is helpful to understand the receptor basis of rational prescribing But we cannot always control all associated symptoms Olanzapine Atypical antipsychotic Dopamine 1, 2, 3 and 4 antagonists 5HT2A, 5HT2C, 5HT3 and 5HT6 antagonist, Alpha-adrenergic antagonist, Histamine-1 antagonist, Muscarinic cholinergic antagonist Acts at the Vomiting Centre T½ 34 hours (↑ 52 hours in the elderly) How best to manage? 1. Surgical opinion & document time for audit *Non-surgical: colic/ high risk perforation or no colic 2. Antiemetic: Stimulant antiemetic/ Non stimulant 3. Laxative (nonstimulant) 4. Steroid s/c or IV (NNT 6) 5. NG/ antisecretory 6. Fluids MEDICAL-SURGICAL NAUSEA AND VOMITING Medical management of bowel obstruction Causes of bowel obstruction: Intraluminal Extraluminal Motility disorders (tumour infiltration, neuropathic damage to GIT, drugs such as opioids, NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL STRATEGIES: Avoiding food with strong tastes and smells Small but frequent meals Control of malodour (strong unpleasant smell) from wounds or ulcers anticholinergics etc) Constipation/ fecal impaction Systematic review of surgery for malignant bowel obstruction: • Control of symptoms 42-80% • Re-obstruction rates 10-50% (most studies did not describe time scales) • Wide range of post op morbidity & mortality Gynaecological Oncology: • Major surgical mobidity 22% - fistula/ abscess/ PE/ peritonitis/ sepsis • Perioperative mortality 6% BRISTOL TOOL CHART Behavioural approaches (e.g. distraction, relaxation) Acupuncture/acupressure MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING i. About the disease ii. Epidemiology iii. Risk factors iv. Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis v. Clinical Presentation (Signs/Symptoms) vi. Assessment/Diagnostic Findings vii. Treatment/Management RISK FACTORS Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Variceal bleeding is UGIB caused by esophageal or gastric varices. Non-variceal bleeding is caused by any etiology of UGIB other than varices. ABOUT THE DISEASE Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) common clinical problem GIB traditionally divided into either upper, lower or acute and chronic Can divide causes into: variceal and nonvariceal Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB): bleeding from any source proximal to ligament of Treitz Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, mortality of UGIB remains from 5– 14% Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB): bleeding from any source distal to ligament of Treitz Mortality higher in patients > 60 yrs old and in patients with multiple comorbid conditions 20-30% of patients will have two or more diagnoses of UGIB. No disease is found in 10-15% of patients (prognosis is excellent). Bleeding peptic ulcer disease most common etiology and is also the most widely studied It was named after the Austrian physician and anatomist Wenzel Treitz, who in 1853 first described the ligament as a thin, triangular, fibromuscular band extending from the upper, surface of the duodenojejunal junction. It is also known as the suspensory ligament of the duodenum because it suspends the duodenojejunal flexure from the retroperitoneum. EPIDEMIOLOGY UGIB is more common than LGIB UGIB approx. 67/100,000 population LGIB approx. 36/100,000 population LGIB: More common with increasing age More common in men Other causes: Dieulafoy’s lesion (bleeding dilated vessel that erodes through the gastrointestinal epithelium but has no primary ulceration; can any location along the GI tract). Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE; also known as watermelon stomach). Cameron lesions (bleeding ulcers occurring at the site of a hiatal hernia). Post-surgical bleeds (post-anastomotic bleeding, post-polypectomy bleeding, post-sphincterotomy bleeding). Hemobilia (bleeding from the biliary tract). Mortality rate 2 - 4% MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding Diverticulosis (colonic wall protrusion at the site of penetrating vessels; over time mucosa overlying the vessel can be injured and rupture leading to bleeding). Angiodysplasia (an abnormal condition of blood vessels of the gastrointestinal tract and especially the intestine in which vessels are thin, fragile, and enlarged) Infectious Colitis Ischemic Colitis Inflammatory Bowel Disease Colon cancer CLINICAL PRESENTATION Hemorrhoids Anal fissures (narrow opening or crack of considerable length and depth usually occurring from some breaking or parting) Haematemesis Vomiting of blood whether fresh and red or digested and black. Melaena Passage of loose, black tarry stools with a characteristic foul smell. Rectal varices Coffee ground vomiting Blood clot in the vomitus. Dieulafoy’s lesion (a medical condition Hematochezia Passage of bright red blood per rectum, usually indicates bleeding from the lower GI tract, but can occasionally be the presentation for a briskly bleeding upper GI source characterized by a large tortuous arteriole most commonly in the stomach wall (submucosal) that erodes and bleeds) Radiation colitis Post-surgical (post-polypectomy bleeding, post *The presence of frank bloody emesis suggests more active and severe bleeding in comparison to coffeeground emesis. *Lower GI bleeding classically presents with hematochezia, however bleeding from the right colon or the small intestine can present with melena. biopsy bleeding) PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS *Bleeding from the left side of the colon tends to present bright red in color, whereas bleeding from the right side of the colon often appears dark or maroon-colored and may be mixed with stool. *Majority of patients with UGIB will spontaneously cease. *70-80% will stop within first 48 hrs of onset; of those 1020% will have recurrence of UGIB. At initial presentation approximately 20% will continue to bleed. *Mortality greatest in these patients and also patients that have recurrent bleeding DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Occasionally, hemoptysis may be confused for hematemesis or vice versa. Ingestion of bismuth containing products or iron supplements may cause stools to appear melanic. Certain foods/dyes may turn emesis or stool red, purple, or maroon MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING ASSESSMENT/DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS Initial Evaluations Monitor hemodynamic status; look for signs of hemodynamic instability Resting tachycardia: associated with the loss of less than 15% total blood volume Orthostatic Hypotension: carries an association with the loss of approximately 15% total blood volume Supine Hypotension: associated with the loss of approximately 40% total blood volume Confirm UGI source of bleeding by: history (hematemesis – fresh blood or coffee ground emesis, melena) Nasogastric aspiration is 80% sensitive for actively bleeding UGI source *False negative aspirates occur when the tube is improperly positioned or when reflux of blood from a duodenal source prevented by pylorospasm or obstruction Acute management of UGIB typically involves: Assessment of the appropriate setting Resuscitation Supportive therapy Investigating the underlying cause and attempting to correct it. Setting Intensive Care Unit *Patients with hemodynamic instability, continuous bleeding, or those with a significant risk of morbidity/mortality should undergo monitoring in an intensive care unit to facilitate more frequent observation of vital signs and more emergent therapeutic intervention. *Most patients with GI bleeding will require hospitalization. However, some young, healthy patients with self-limited and asymptomatic bleeding may be safely discharged and evaluated on an outpatient basis. Resuscitation Things to consider: Laboratory Evaluations Complete blood count Hemoglobin/Hematocrit INR, PT, PTT (International Normalized Ratio, Prothrombin Time, Partial Thromboplastin Time) Liver and renal function tests Nothing by mouth Adequate IV access - at least two large-bore peripheral IVs or a centrally placed. Provide supplemental oxygen if patient hypoxic (typically via nasal cannula, but patients with ongoing hematemesis or altered mental status may require intubation). Fluid/s: TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT Risk Stratification Specific risk calculators attempt to help identify patients who would benefit from ICU level of care; most stratify based on mortality risk. The Rockall Score calculate the mortality rate of upper GI bleeds. There are two separate Rockall scores; one is calculated before endoscopy and identifies preendoscopy mortality, whereas the second score is calculated post-endoscopy and calculates overall mortality and re-bleeding risks. IV fluid resuscitation (with Normal Saline or Lactated Ringer’s solution) Type and Cross matching Transfusions: RBC transfusion; typically started if hemoglobin is < 7g/dL, including cardiac patients. Platelet transfusion; started if platelet count < 50,000. Prothrombin complex concentrate; if INR > 2 Medications: PPIs: Bolus (80 mg), followed by maintenance (8 mg/kg/hr) 3-5 days-significant benefit in decreasing recurrent bleeding. Vasoactive medications: Somatostatin and its analog octreotide can be used to treat variceal bleeding by inhibiting vasodilatory hormone release. Erythromycin: Given to improve visualization at the time of endoscopy. Antibiotics: Considered prophylactically in patients with cirrhosis to prevent SBP, especially from endoscopy MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING Anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents: Should be stopped if possible in acute bleeds. Consider the reversal of agents on a case-by-case basis dependent on the severity of bleeding and risks of reversal. Thermal: Multipolar electrocautery / electrocautery and Argon plasma coagulation Other procedures: Placement of a sengestaken tube should be considered in patients with hemodynamic instability/massive GI bleeds in the setting of known varices, which should be done only once the airway is secured. Injection: Epinephrine Mechanical: Band Ligation, Hemoclips (Endoclip) This procedure carries a significant complication risk (including arrhythmias, gastric or esophageal perforation) and should only be done by an experienced provider. Endoscopy Can be diagnostic and therapeutic. It is the test of choice for identifying and treating the bleeding lesion Allows visualization of the upper GI tract (typically including from the oral cavity up to the duodenum) and treatment with injection therapy, thermal coagulation, hemostatic clips/bands or band ligation. No role for barium studies in acute UGIB Greatest benefit in the ~20% of patients with continued or recurrent bleeding Improve morbidity and decreased by nearly 30%. mortality: mortality Active bleeding can be controlled in 85-90% of patients, with less than 3% complication rate. Should be done within 12-24 hrs. Endoscopic Management: Several endoscopic therapeutic techniques available to attempt hemostasis in patients with UGIB Algorithm bipolar MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTRITIS GASTRITIS i. About the disease ii. Epidemiology iii. Risk factors iv. Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis v. Types vi. Clinical Presentation (Signs/Symptoms) vii. Assessment/Diagnostic Findings viii. Treatment/Management PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS The impaired mucosal barrier allows corrosive HCL, pepsin, and other irritating agents (e.g., NSAIDs and H. pylori) to come in contact with the gastric mucosa, resulting in inflammation. Described as a discontinuity in gastric and duodenal mucosa exposed to acid or pepsin. Loss of balance between mucosal protective mechanism and aggressive factors of acid and pepsin production. In acute gastritis, this inflammation is usually transient and self-limiting in nature. Inflammation causes the gastric mucosa to become edematous and hyperemic (congested with fluid and blood) and to undergo superficial erosion. Superficial ulceration may occur as a result of erosive disease and may lead to hemorrhage In chronic gastritis, persistent or repeated insults lead to chronic inflammatory changes, and eventually atrophy (or thinning) of the gastric tissue. ABOUT THE DISEASE Microscopic evidence of inflammation affecting the gastric mucosa Gastritis is characterized by a disruption of the mucosal barrier that normally protects the stomach tissue from digestive juices (e.g., hydrochloric acid [HCl] and pepsin) EPIDEMIOLOGY It affects women and men about equally and is more common in older adults RISK FACTORS Primary Gastritis: 10% occurrence in western Countries Up to 100% in under developed countries Primary duodenal ulcer almost always Very rare in children below 1 year TYPES Gastritis may be acute, lasting several hours to a few days, or chronic, resulting from repeated exposure to irritating agents or recurring episodes of acute gastritis. Acute Gastritis Secondary Gastritis: Severe Stress (Systemic illness, Burns Head injury) NSAID (Ibuprofen, mefanamic acid) *Inhibit HCo3 secretion Acute Gastritis can be classified into two types: EROSIVE and NON-EROSIVE Erosive Gastritis Often caused by irritants such as: *5 folds High risk of massive bleeding Cauresive gastritis mainly esophagus Crohn’s disease Aspirin or NSAIDs (ibuprofen [Motrin]) Alcohol consumption Radiation therapy Non-erosive gastritis *30% ulcer Often caused by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) *Can occur at any age *Associated with high mortality Severe form of acute gastritis Others Caused by the ingestion of strong acid or alkali, which may cause the mucosa to become gangrenous or to perforate Scarring can occur, resulting in pyloric stenosis (narrowing or tightening) or obstruction. *Iron, Kcl *Antibiotics Penicillin Tetracyclin Cephalosporin Stress-related gastritis Acute gastritis may also develop in acute illnesses: Major traumatic injuries Burns Severe infection Hepatic, kidney, or respiratory failure Major surgery MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTRITIS Chronic Gastritis CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Chronic H. pylori gastritis is implicated in the development of: Peptic ulcers Gastric adenocarcinoma Gastric mucosa-associated tissue lymphoma lymphoid Chronic gastritis may also be caused by a chemical injury (gastropathy) ACUTE GASTRITIS Epigastric pain or discomfort Dyspepsia (indigestion) Anorexia Hiccups Nausea and vomiting Erosive gastritis may cause bleeding: Long-term drug therapy—aspirin and other NSAIDs Reflux of duodenal contents into the stomach Often occurs after gastric surgery Blood in vomit Melena (black, tarry stools) Hematochezia (bright red, bloody stools) CHRONIC GASTRITIS Autoimmune disorders are also associated with the development of chronic gastritis: Hashimoto thyroiditis Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis that is characterized by thyroid enlargement, thyroid fibrosis, lymphatic infiltration of thyroid tissue, and the production of antibodies which attack the thyroid Fatigue Pyrosis (heartburn) after eating Belching Sour taste Early satiety Anorexia Nausea and vomiting Some patients may only have mild epigastric discomfort relieved by eating or intolerance to spicy or fatty foods. Patients may not be able to absorb vitamin B12 which may lead to pernicious anemia. Diminished production of intrinsic factor by the parietal cells due to atrophy. Some patients have no symptoms Addison disease Destructive disease marked by deficient adrenocortical secretion and characterized by extreme weakness, loss of weight, low blood pressure, gastrointestinal disturbances, and brownish pigmentation of the skin and mucous membranes Graves’ disease Common form of hyperthyroidism that is an autoimmune disease characterized by goiter, rapid and irregular heartbeat, weight loss, irritability, anxiety, and often a slight protrusion of the eyeballs ASSESSMENT/DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS The definitive diagnosis of gastritis is determined by an endoscopy and histologic examination of a tissue specimen obtained by biopsy. A complete blood count (CBC) may be drawn to assess for anemia as a result of hemorrhage or pernicious anemia. Diagnostic measures for detecting H. pylori infection may be used. MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTRITIS Barium contrast study not sensitive about 40% missed Metronidazole (Flagyl) *Assists with eradicating H. pylori when given with other antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT ACUTE GASTRITIS Should be given with meals to decrease GI upset; may cause anorexia and metallic taste Patient should avoid alcohol; increases blood-thinning effects of warfarin *The gastric mucosa is capable of repairing itself. • Patient recovers in 1 day. • Appetite may be diminished for 2 or 3 days. Instruct patient to refrain from alcohol and food until symptoms subside. A nonirritating diet is recommended. If symptoms persist, IV fluids may be given. Fiberoptic endoscopy. Emergency surgery to remove gangrenous or perforated tissue. Gastric resection or gastrojejunostomy to treat gastric outlet obstruction (pyloric obstruction). CHRONIC GASTRITIS Modify diet Promote rest Reduce stress Avoid alcohol and NSAIDs Medications—antacids, H2 blockers, or PPIs H. pylori—PPI, antibiotics, and bismuth salts Tetracycline *Exerts bacteriostatic effects to eradicate H. pylori May cause photosensitivity reaction; advise patient to use sunscreen May cause GI upset Must be used with caution in patients with renal or hepatic impairment Milk or dairy products may reduce effectiveness ANTI-DIARRHEAL Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) *Suppresses H. pylori PHARMACOTHERAPY *Assists with healing of ulcers ANTIBIOTICS Amoxicillin (Amoxil) *A bactericidal antibiotic that assists with eradicating H. pylori Given concurrently with antibiotics Should be taken on empty stomach May cause diarrhea Should not be used in patients allergic to penicillin H2 RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS Cimetidine (Tagamet) Clarithromycin (Biaxin) * Decreases amount of HCl produced * Exerts bactericidal effects to eradicate H. pylori May cause altered taste GI upset, by blocking action of histamine on histamine receptors of parietal cells in headache, Many drug-drug interactions o o o Colchicine [Colcrys] Lovastatin [Mevacor] Warfarin [Coumadin] the stomach Least expensive May cause confusion, agitation, or coma in older adults or those with renal or hepatic insufficiency Long-term use may cause diarrhea, dizziness, and gynecomastia MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTRITIS and vomiting, or abdominal Many drug-drug interactions o Amiodarone [Cordarone] discomfort. o Amitriptyline [Elavil) o Benzodiazepines PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS o Metoprolol (Lopressor) Esomeprazole (Nexium) o Nifedipine (Procardia) o Phenytoin [Dilantin] *decreases gastric acid secretion by o Warfarin slowing H+, K+ ATPase pump on the surface of the parietal cells of the stomach Famotidine (Pepcid) *same action as Cimetidine Used mainly for treatment of duodenal ulcer Best for patient who is and H. pylori infection critically ill because it is To be swallowed whole and taken known before meals Having the least risk of Lansoprazole (Prevacid), Omeprazole drug-drug interactions; Does not alter (Prilosec), Pantoprazole (Protonix) and liver Rabeprazole (Aciphex) metabolism Prolonged in *decreases gastric acid secretion by renal slowing H+, K+ ATPase pump on the half-life patients with surface of the parietal cells insufficiency Short-term relief for GERD To be swallowed whole and taken before meals Nizatidine (Axid) May cause diarrhea, nausea, constipation, abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, or *same action Cimetidine dizziness Used for treatment of ulcers and Drug-drug interactions (Rabeprazole) GERD Prolonged half-life in patients o Digoxin with renal insufficiency o Iron May o Warfarin cause headache, dizziness, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, GI upset, and PROSTAGLANDIN E1 ANALOG urticaria Misoprostol (Cytotec) *Protects the gastric mucosa from Ranitidine *same action as Cimetidine ulcers *Increases mucus production and Prolonged half-life in patients with renal and hepatic insufficiency May cause headache, dizziness, constipation, nausea Used to prevent ulceration in patients using Causes fewer side effects than cimetidine bicarbonate levels NSAIDs Administer with food MEDICAL-SURGICAL GASTRITIS May cause cramping diarrhea (including and uterine cramping) Used mainly for the treatment Promoting fluid balance • Minimal fluid intake – 1.5 L/day of duodenal ulcers • Minimal urine output – 0.5 mL/kg/h • IV fluids – 3 L/day • 1L D5W = 170 calories of carbohydrate Sucralfate (Carafate) • Electrolyte values (sodium, potassium, *Creates a viscous substance that forms a protective barrier, binding chloride) are assessed every 24 hours. to the ulcer, and prevents digestion • The nurse must always be alert to any by pepsin indicators of hemorrhagic gastritis: Should be taken without food Hematemesis (vomiting of blood) Tachycardia Other medications should be Hypotension taken 2 hours before or after Stool: frank or occult bleeding this medication Notify but with water May cause constipation primary provider and monitor vital signs. or nausea Relieving pain • Instruct patient to avoid foods and NURSING MANAGEMENT beverages that may irritate the gastric Reducing anxiety mucosa. Promoting optimal nutrition • Medications to relieve chronic gastritis • NPO until symptoms subside, allowing the EDUCATING PATIENTS ABOUT SELF-CARE gastric mucosa to heal. • IV therapy Stress management Monitor I&O and electrolytes • After symptoms subside, offer patient ice Diet • Foods and substances to be avoided: chips followed by clear liquids. Introduce solid food as soon as possible. Spicy, irritating, or highly seasoned foods Provides adequate nutrition Decreases the need for IV therapy Caffeine Minimize Nicotine Alcohol irritation to the gastric mucosa • As food is introduced, report symptoms Medications that suggest a repeat episode. • Reinforce the importance of completing the • Discourage caffeinated beverages. medication regimen to eradicate H. pylori. Caffeine is a CNS stimulant that CONTINUING AND TRANSITIONAL CARE increases pepsin secretion. Discourage alcohol use. Discourage smoking. Nicotine reduces Patients with vitamin B12 malabsorption need information about lifelong vitamin B12 injections. the secretion of pancreatic bicarbonate, which inhibits the neutralization of gastric acid in the duodenum. MEDICAL-SURGICAL PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE i. About the disease ii. Epidemiology iii. Risk factors iv. Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis v. Types vi. Clinical Presentation (Signs/Symptoms) vii. Assessment/Diagnostic Findings viii. Complications ix. Treatment/Management bacteria also occurs through close contact and exposure to emesis smoking and alcohol consumption may be risks *although the evidence is inconclusive Familial tendency also may be a significant predisposing factor. *People with blood type O are more susceptible to the development of peptic ulcers. ABOUT THE DISEASE Erosion of GI mucosa resulting from digestive action of hydrochloric acid and pepsin A peptic ulcer may be referred to as a gastric, duodenal, or esophageal ulcer, depending on its location. A peptic ulcer is an excavation (hollowed-out area) that forms in the mucosa of the stomach, in the pylorus (the opening between the stomach and duodenum), in the duodenum or in the esophagus There also is an association between peptic ulcer disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis of the liver, and chronic kidney disease. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome *a rare condition in which benign or malignant tumors form in the pancreas and duodenum that secrete excessive amounts of the hormone Erosion of a circumscribed area of mucosa is the cause gastrin Excessive amount of gastrin An inherited, genetic condition called multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 1 (MEN 1) PATHOPHYSIOLOGY This erosion may extend as deeply as the muscle layers or through the muscle to the peritoneum (thin membrane that lines the inside of the wall of the abdomen) Peptic ulcers are more likely to occur in the duodenum than in the stomach. EPIDEMIOLOGY Women and men have about equivalent lifetime risk of developing peptic ulcers. The rates of peptic ulcer disease among middleaged adults have diminished over the past several decades, whereas the rates among older adults have increased. Those who are 65 years and older present to both outpatient and inpatient settings for treatment of peptic ulcers more than any other age group. RISK FACTORS use of NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and aspirin infection with the gram-negative bacteria H. pylori *which may be acquired through ingestion of food and water; person-to-person transmission of the The erosion is caused by the increased concentration or activity of acid–pepsin or by decreased resistance of the normally protective mucosal barrier. The use of NSAIDs inhibits prostaglandin synthesis, which is associated with a disruption of the normally protective mucosal barrier. Person with a gastric ulcer has normal to less than normal gastric acidity compared with person with a duodenal ulcer. MEDICAL-SURGICAL PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE TYPES Acute Superficial erosion Minimal erosion Chronic Muscular wall erosion with formation of fibrous tissue Present continuously for many months or intermittently CLINICAL PRESENTATION Common to have no pain or other symptoms *These silent peptic ulcers most commonly occur in older adults and those taking aspirin and other NSAIDs Stress ulcer is the term given to the acute mucosal ulceration of the duodenal or gastric area that occurs after physiologically stressful Gastric and duodenal mucosa not rich in sensory pain fibers Duodenal ulcer pain (Burning, cramplike) Gastric ulcer pain (Burning, gaseous) Dull, gnawing pain or a burning sensation in the mid-epigastrium or the back events, such as burns, shock, sepsis, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Specific types of ulcers that result from stressful conditions include Curling ulcers and Cushing ulcers. DIFFERENCE BETWEEN GASTRIC ULCER DUODENAL AND Association of pain: GASTRIC ULCER: almost immediately after eating Curling ulcer is frequently observed about 72 hours after extensive burn injuries and DUODENAL ULCER: commonly occurs 2 to 3 hours after meals often involves the antrum of the stomach or the duodenum. Occurrence: GASTRIC ULCER: 30% to 40% of patients awake with pain during the night Cushing ulcer is common in patients with a traumatic DUODENAL ULCER: 50% to 80% of patients voice the same type of complaint head injury, stroke, brain tumor, or following intracranial surgery. Patients with duodenal ulcers are more likely to express relief of pain after eating or after taking an antacid than patients with gastric ulcers. MEDICAL-SURGICAL PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE Other nonspecific symptoms of either gastric Vomiting is rare in an uncomplicated peptic ulcer, it may be a symptom of a complication of an ulcer. Peptic ulcer perforation Bleeding peptic ulcers may present with evidence of GI bleeding, such as hematemesis (vomiting blood) or the passage of melena (black, tarry stools) ulcers or duodenal ulcers may include: pyrosis vomiting constipation or diarrhea bleeding *These symptoms are often accompanied by sour eructation (burping), which is common when the patient’s stomach is empty TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT Pharmacologic Therapy ASSESSMENT/DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS Physical examination may reveal pain, epigastric tenderness, or abdominal distention. Upper endoscopy is the preferred diagnostic procedure because it allows direct visualization of inflammatory changes, ulcers, and lesions The most commonly used therapy for peptic ulcers is a combination of antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, and sometimes bismuth salts that suppress or eradicate H. pylori. Recommended combination drug therapy is typically prescribed for 10 to 14 days and may include triple therapy with two antibiotics plus a proton pump. Quadruple therapy with two antibiotics plus a proton pump inhibitor and bismuth salts Use of: Antacids o Used as adjunct therapy for peptic ulcer disease Serologic testing for antibodies against the H. ↑ gastric pH by neutralizing acid pylori antigen, stool antigen test, and urea breath test Barium contrast studies H2 receptor blockers o Used to manage peptic ulcer disease o Block action of histamine on H2 receptors Widely used ↓ HCl acid secretion X- ray studies ↓ conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin May be ineffective in differentiating a peptic ulcer from a malignant tumor ↑ ulcer healing Gastric analysis Lab analysis COMPLICATIONS 3 major complications: Hemorrhage Perforation Gastric outlet obstruction *Initially treated conservatively *May require surgery at any time during course of therapy PPIs Antibiotics Anticholinergics Cytoproctective therapy The patient is advised to adhere to and complete the medication regiment to ensure complete healing of the ulcer. The patient is advised to avoid the use of aspirin and other NSAIDs. Smoking Cessation Smoking decreases the secretion of bicarbonate from the pancreas into the duodenum, resulting in increased acidity of the duodenum. MEDICAL-SURGICAL PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE Continued smoking is also associated with delayed healing of peptic ulcers. Lifestyle changes to prevent recurrence Surgical procedures Dietary Modifications The intent of dietary modification for patients with peptic ulcers is to avoid oversecretion of acid and hypermotility in the GI tract. Dietary modifications may be necessary so that foods and beverages irritating to patient can be avoided or eliminated Nonirritating or bland diet consisting of 6 small meals a day during symptomatic phase Protein considered best neutralizing food *Stimulates gastric secretions Carbohydrates and fats are least stimulating to Vagotomy (severing of the vagus nerve) *it decreases gastric acid by diminishing cholinergic stimulation to the parietal cells, making them less responsive to gastrin. With or without pyroloplasty *transecting nerves that stimulate acid secretion and opening the pylorus) Antrectomy *removal of the lower portion of the antrum (which contains cells of gastrin) HCl acid secretion *Do not neutralize well Avoiding extremes of temperature in food and beverages and overstimulation from the consumption of alcohol, coffee (including decaffeinated coffee, which also stimulates acid secretion), and other caffeinated beverages. An effort is made to neutralize acid by eating three regular meals a day (small, frequent feedings) Surgical Management Surgery is usually recommended for patients with intractable ulcers (those failing to heal after 12 to 16 weeks of medical treatment), lifethreatening hemorrhage, perforation, or obstruction and for those with ZES that is unresponsive to medications. Remember the word: ANASTMOSIS (surgical connection) Indications for surgical interventions: Intractability History of hemorrhage, ↑ risk of bleeding Prepyloric or pyloric ulcers Drug-induced ulcers Possible existence of a malignant ulcer Obstruction Goals of having surgery: prescribed therapeutic Experience a reduction or absence of discomfort related to peptic ulcer disease Exhibits no signs of GI complications Have complete healing Gastroduodenostomy or BILLROTH I *The pylorus is removed and the distal stomach is anastomosed directly to the duodenum. Multiple ulcer sites Comply with regimen MEDICAL-SURGICAL PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE Gastrojejunostomy or BILLROTH II *The pylorus is removed and the distal stomach is anastomosed directly to the jejunum. Surgery may be performed using a traditional open abdominal approach (requiring a long abdominal incision) or through the use of laparoscopy (only requiring small abdominal incisions). Follow-up care Recurrence of peptic ulcer disease within 1 year may be prevented with the prophylactic use of H2 blockers taken at a reduced dose. . The likelihood of recurrence is reduced if the patient avoids smoking, coffee (including decaffeinated coffee) and other caffeinated beverages, alcohol, and ulcerogenic medications (e.g., NSAIDs). MEDICAL-SURGICAL MALABSORPTION MALABSORPTION i. About the disease ii. Risk factors iii. Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis iv. Clinical Presentation (Signs/Symptoms) v. Assessment/Diagnostic Findings vi. Treatment/Management ABOUT THE DISEASE The inability of the digestive system to absorb one or more of the major vitamins (especially A and B12), minerals (i.e., iron and calcium), and nutrients (i.e., carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) occurs in disorders of malabsorption. Interruptions in the complex digestive process may occur anywhere in the digestive system and cause decreased absorption. RISK FACTORS Mucosal (transport) disorders causing generalized malabsorption (e.g., celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, radiation enteritis) Luminal disorders causing malabsorption (e.g., bile acid deficiency, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, pancreatic insufficiency, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, or chronic pancreatitis) Lymphatic obstruction, interfering with transport of fat by products ofdigestion into the systemic circulation (e.g., neoplasms, surgical trauma). *Characteristics of stools as recorded on the BSFS are then used to determine category of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), where IBS-C (constipation), IBS-D (diarrhea), IBS-M (mixed), and IBS-U (uncategorized). *Table below shows the selected disorders of malabsorption MEDICAL-SURGICAL MALABSORPTION PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (3) impaired enterohepatic bile circulation, as seen in small bowel resection or regional enteritis; In general, the digestion and absorption of food materials can be divided into 3 major phases: 1. The luminal phase where dietary fats, proteins, and carbohydrates are hydrolyzed and solubilized by secreted digestive enzymes and bile. (4) bile salt deconjugation due to small bowel bacterial overgrowth. . Luminal availability and processing Luminal bacterial overgrowth can cause a decrease in the availability of substrates, including carbohydrates, proteins, and vitamins. 2. The mucosal phase relies on the integrity of the brush-border membrane of intestinal epithelial cells to transport digested products from the lumen into the cells. 3. In the post absorptive phase, nutrients are transported via lymphatics and portal circulation from epithelial cells to others of the body. MUCOSAL PHASE: Impaired brush-border hydrolase activity o Disaccharidase deficiency CAUSES: o Lactase deficiency LUMINAL PHASE: o Immunoglobulin A (IgA) deficiency Impaired nutrient hydrolysis The most common cause is pancreatic insufficiency due to chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic resection, pancreatic cancer, or cystic fibrosis. Acquired disorders are far more common and are caused by: (1) Decreased absorptive surface area, as seen in intestinal resection Inactivation of pancreatic enzymes by gastric hypersecretion, as seen in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (2) Damaged absorbing surface, as seen in celiac sprue, tropical sprue, giardiasis, Crohn disease, AIDS enteropathy, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy; Impaired micelle formation Impaired micelle formation causes lead to fat malabsorption. This impairment is due to different reasons, including (1) decreased bile salt synthesis from severe parenchymal liver disease (eg, cirrhosis); (2) impaired bile secretion from biliary obstruction or cholestatic jaundice (eg, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis); Impaired nutrient absorption (3) Infiltrating disease of the intestinal wall, such as lymphoma and amyloidosis POST ABSORPTIVE PHASE: Obstruction of the lymphatic system, both congenital (eg, intestinal lymphangiectasia) Acquired (eg, Whipple lymphoma, tuberculosis) diseases , MEDICAL-SURGICAL MALABSORPTION ASSESSMENT/DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS Dermatitis herpetiformis, erythema nodosum, and pyoderma gangrenosum may be present. Pellagra, alopecia, or seborrheic dermatitis History: Diarrhea Weight Loss Steatorrhea (an excess of fat in the stools) Flatulence and abdominal distention Edema Anemia Metabolic defects of bones Physical Manifestations: Patients may have orthostatic hypotension. Signs of weight loss, muscle wasting, or both may be present. Patients may have signs of loss of subcutaneous fat Cheilosis, glossitis, or aphthous ulcers of the mouth. Abdominal examination The abdomen may be distended, and bowel sounds may be hyperactive. Ascites may be present in severe hypoproteinemia. Dermatological Manifestations: Pale skin Ecchymoses due to vitamin K deficiency Neurological examination Motor weakness, peripheral neuropathy, or ataxia may be present. The Chvostek sign or the Trousseau sign may be evident due to hypocalcemia. MEDICAL-SURGICAL MALABSORPTION Laboratory Findings: Hematological tests o CBC o Serum iron, vitamin B-12, and folate o Prothrombin time. Electrolytes and chemistries o Hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, and metabolic acidosis. o Protein malabsorption may cause hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia. o Fat malabsorption can lead to low serum levels of triglycerides, cholesterol o ESR which is elevated in Crohn disease and Whipple disease Stool analysis o Stool pH may be assessed. Values of <5.6 are consistent with carbohydrate malabsorption o Pus cell in the stool e.g IBD Schilling test o Malabsorption of vitamin B-12 may occur as a consequence of deficiency of intrinsic factor (eg, pernicious anemia, gastric resection), pancreatic insufficiency, bacterial overgrowth, ileal resection, or disease. TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT A gluten-free diet helps treat celiac disease. Similarly, a lactose-free diet for lactase Protease and lipase supplements are the therapy for pancreatic insufficiency Antibiotics are the therapy for bacterial overgrowth. Corticosteroids, anti-inflammatory agents, such as mesalamine, and other therapies are used to treat celiac disease Nutritional support: Supplementing various minerals calcium, magnesium, iron, and vitamins Caloric and protein replacement also is essential. Medium-chain triglycerides can be used for lymphatic obstruction. In severe intestinal disease, such as massive resection and extensive regional enteritis, parenteral nutrition may become necessary. MEDICAL-SURGICAL OSTEOPOROSIS HIATAL HERNIA i. About the disease ii. Epidemiology iii. Risk factors iv. Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis v. Clinical Presentation (Signs/Symptoms) vi. Assessment/Diagnostic Findings vii. Treatment/Management viii. Gerontologic Considerations Prescribed corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) for longer than 3 months PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS ABOUT THE DISEASE Osteoporosis is the most prevalent bone disease in the world. A disease that causes your bones to become weak and brittle Osteoporosis is important because of the problems resulting from these fractures disability, loss of independence, and even death. Osteoporosis is silent because there are no symptoms (what you feel). Osteoporosis is characterized by reduced bone mass, deterioration of bone matrix, and diminished bone architectural strength. Normal homeostatic bone turnover is altered; the rate of bone resorption that is maintained by osteoclasts (cells that degrade bone to initiate normal bone) remodeling is greater than the rate of bone formation that is maintained by osteoblasts (cells that form bone tissue), resulting in a reduced total bone mass. The gradual collapse of a vertebra may be asymptomatic. Age-related loss begins soon after the peak bone mass is achieved (i.e., in the fourth decade). Calcitonin, which inhibits bone resorption and promotes bone formation, is decreased. Estrogen, which inhibits bone breakdown, also decreases with aging. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) increases with aging, thus increasing bone turnover and resorption. Osteoporosis is not an inevitable part of aging, but is a disease that can be prevented and treated, provided it is detected early. The main goal of treating osteoporosis is to prevent such fractures in the first place. EPIDEMIOLOGY More than 1.5 million osteoporotic fractures occur every year Fractures requiring hospitalization have risen significantly over the past two decades It is estimated that a 50 year-old woman has a 40% chance of having an osteoporotic fracture during her remaining lifetime. It is projected that one of every two Caucasian women and one of every five men will have an osteoporosis-related fracture at some point in their lives RISK FACTORS Alcohol intake of 3 or more drinks daily Current use of tobacco products Family history History of bone fracture during adulthood Inactive or sedentary lifestyle Inadequate calcium and vitamin D intake Low body mass index Malabsorption disorders (e.g., eating disorder, celiac disease, bariatric surgery) Men older than 60 years of age Women who are postmenopausal MEDICAL-SURGICAL OSTEOPOROSIS CLINICAL PRESENTATION Simple test that measures bone mineral density. Often the measurements are at your spine and your hip, including a part of the hip called the femoral neck, at the top of the thighbone (femur). The test is quick and painless. The postural changes result in relaxation of the abdominal muscles and a protruding abdomen. It is similar to an X-ray, but uses much less radiation. Deformity may also produce pulmonary insufficiency and increase the risk for falls related to balance issues. Even so, pregnant women should not have this test, to avoid any risk of harming the fetus. Question: Who needs bone densitometry? Anyone who wants an accurate measurement of bone density. However, because of cost concerns, the test is most often done for those with high risk of developing osteoporosis, or to monitor the effectiveness of treatment for osteoporosis. Estrogen deficient women undecided about taking hormones. This is a way of measuring the amount of calcium in a certain amount of bone. Those with spinal abnormalities evidence of bone loss. This is important because the amount of calcium in your bone determines how strong it is. Anyone taking long-term corticosteroid treatment (such as Prednisone). If the bone density is very low, then you have osteoporosis and a very high risk of fracturing your bones. Primary hyperparathyroidism with no symptoms. Monitoring of therapy for osteoporosis. ASSESSMENT/DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS Osteoporosis may be undetectable on routine xrays until there has been significant demineralization, resulting in radiolucency of the bones. BONE DENSITOMETRY or X-ray DUAL-ENERGY X-RAY ABSORPTIOMETRY Fracture risk can be estimated using the World Health Organization (WHO) Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX). DEXA scan data are analyzed and reported as T-scores (the number of standard deviations above or below the average BMD value for a 30-year-old healthy Caucasian woman). MEDICAL-SURGICAL OSTEOPOROSIS Calcitonin Other diagnostic tests used: Laboratory studies Serum calcium, Serum phosphate, Serum alkaline phosphatase [ALP], Urine calcium excretion, Urinary hydroxyproline excretion Hematocrit Erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] X-ray studies This medication, a hormone made from the thyroid gland, is given most often as a nasal spray or as an injection (shot) under the skin. Approved for the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis and helps prevent vertebral (spine) fractures. It also is helpful in controlling pain after an osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Estrogen or hormone replacement therapy Estrogen treatment alone or combined with another hormone, progestin, has been shown to decrease the risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures in women. Consult with your doctor about whether hormone replacement therapy is right for you. Differential diagnosis: Multiple myeloma Osteomalacia Hyperparathyroidism Malignancy Selective estrogen receptor modulators TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT A diet rich in calcium and vitamin D throughout life, with an increased calcium intake during adolescence and the middle years, protects against skeletal demineralization. The recommended adequate intake level of calcium for men 50 to 70 years is 1000 mg daily, and for women aged 51 and older and men aged 71 and older is 1200 mg daily. The recommended vitamin D intake for adults up to 70 years of age is 600 IU daily, and 800 IU daily for those over the age of 70. Regular weight-bearing exercise promotes bone formation. Recommendations include 20 to 30 minutes of aerobic, bone-stressing exercise daily. Pharmacologic Therapy To ensure adequate calcium intake, a calcium supplement (e.g., Caltrate, Citracal) with vitamin D may be prescribed and taken with meals or with a beverage high in vitamin C to promote absorption Bisphosphonates This class of drugs (often called “antiresorptive” drugs) helps slow bone loss. Studies show they can decrease the risk of fractures. With all of these medications, you should make sure you are taking enough calcium and vitamin D, and that the vitamin D levels in your body are not low. These medications, often referred to as SERMs, mimic estrogen’s good effects on bones without some of the serious side effects such as breast cancer. Teriparatide Teriparatide is a form of parathyroid hormone that helps stimulate bone formation. It is approved for use in postmenopausal women and men at high risk of osteoporotic fracture. It also is approved for treatment glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. It is given as a daily injection under the skin and can be used for up to two years. of MEDICAL-SURGICAL OSTEOPOROSIS *Table that shows selected osteoporosis medications GERONTOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS The prevalence of osteoporosis in women older than 80 years is 50%. The average 75-year-old woman has lost 25% of her cortical bone and 40% of her trabecular bone. Older adults absorb dietary calcium less efficiently and excrete it more readily through their kidneys. Postmenopausal women and older adults need to consume approximately 1200 mg of daily calcium. Quantities larger than this may place patients at heightened risk of renal calculi or cardiovascular disease.