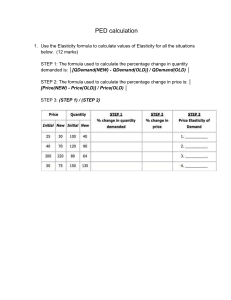

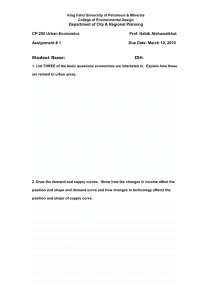

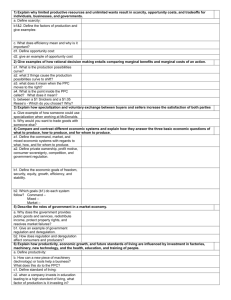

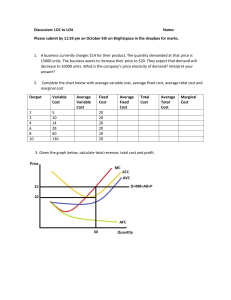

FUNDAMENTALS Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms in markets. The fundamental principles of microeconomics, including the concept of opportunity cost, the role of prices in determining allocation of resources, and the basic principles of supply and demand. 1. Scarcity: Scarcity refers to the limited nature of resources. Because resources are limited, individuals and firms must make choices about how to allocate these resources in order to satisfy their needs and wants. For example, a person may have to choose between buying a new car or saving for a down payment on a house, because they do not have enough money to do both. 2. Opportunity cost: Opportunity cost is the cost of a decision in terms of the next best alternative that must be given up. For example, if a person spends an hour studying for a test, the opportunity cost is the time that could have been spent on other activities, such as watching a movie or playing a sport. 3. Marginal analysis: Marginal analysis is the process of evaluating the additional benefits and costs of a decision. It involves comparing the marginal (or additional) benefit of an action to the marginal cost. If the marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost, the decision is likely to be a good one. For example, if a person is considering taking an additional course in college, they may weigh the marginal benefit (such as the increased earning potential that may come with a degree in that subject) against the marginal cost (such as the tuition and opportunity cost of time spent in the course). 4. Demand: Demand is the quantity of a good or service that consumers are willing and able to purchase at a given price. Demand is typically represented graphically as a downward-sloping curve, with the quantity demanded increasing as the price decreases. Factors that can affect demand include income, prices of related goods, consumer expectations, and the number of consumers in the market. 5. Supply: Supply is the quantity of a good or service that firms are willing and able to produce and sell at a given price. Supply is typically represented graphically as an upward-sloping curve, with the quantity supplied increasing as the price increases. Factors that can affect supply include production costs, prices of inputs, technology, and the number of firms in the market. 6. Market equilibrium: Market equilibrium is the point at which the quantity of a good or service demanded by consumers is equal to the quantity supplied by firms. At this point, there is no excess demand or excess supply, and the market is in balance. The equilibrium price is determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves. 7. Elasticity: Elasticity is the degree to which the quantity demanded or supplied of a good or service changes in response to a change in price. A good or service is said to be elastic if the quantity demanded or supplied changes significantly in response to a change in price. Inelastic goods or services, on the other hand, have a relatively small change in quantity demanded or supplied in response to a change in price. Elasticity is an important concept in microeconomics because it helps to predict how changes in price will affect the quantity of a good or service that is bought or sold. 8. Market failure: Market failure occurs when the market fails to allocate resources efficiently. This can happen for a variety of reasons, including externalities (costs or benefits that are not reflected in the market price), public goods (goods that are nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption), and market power (the ability of a firm or group of firms to influence prices in a market). In these cases, government intervention may be necessary to correct the market failure and promote more efficient resource allocation. Opportunity cost is the cost of a decision in terms of the next best alternative that must be given up. It is an important concept in economics because it helps individuals and firms make rational decisions by taking into account the costs and benefits of different options. For example, if a person has limited time and money, they may have to choose between taking a vacation or investing in their education. The opportunity cost of taking a vacation is the money and time that could have been spent on education, while the opportunity cost of investing in education is the enjoyment and relaxation that could have been gained from taking a vacation. Trade-offs are the choices that individuals and firms must make as a result of scarcity. Because resources are limited, it is not possible to have everything that we want, so we must decide what is most important to us and allocate our resources accordingly. For example, a person may have to choose between spending money on a new car or saving for retirement, because they do not have enough money to do both. Opportunity cost and trade-offs are closely related concepts. When making a decision, individuals and firms must consider the opportunity cost of their choices and the trade-offs they are willing to make in order to achieve their goals. The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility is a principle in economics that states that as the quantity of a good or service consumed increases, the marginal utility (additional satisfaction or benefit) derived from consuming each additional unit of the good or service will decrease. In other words, the first unit of a good or service that is consumed is typically more valuable to an individual than the second unit, and the second unit is typically more valuable than the third unit, and so on. The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility is based on the idea that people have finite needs and wants, and as they consume more of a good or service, they become satiated and derive less additional utility from consuming additional units. For example, an individual who is hungry will typically derive more utility from consuming the first slice of pizza than from consuming the second slice, because the first slice satisfies their hunger to a greater extent. The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility has important implications for consumer behavior and the demand for goods and services. It suggests that as the price of a good or service increases, the quantity demanded will decrease, because the additional utility derived from consuming additional units of the good or service will decrease as the quantity consumed increases. TYPES OF ECONOMIES: There are several types of economies, including: 1. Traditional economy: This is an economy in which the production and distribution of goods and services are based on long-established customs and traditions. In a traditional economy, economic decisions are made based on the customs and beliefs of the community. 2. Market economy: This is an economy in which the production and distribution of goods and services are based on the interaction of supply and demand in a free market. In a market economy, economic decisions are made by individuals and firms, who are motivated by the profit motive. 3. Command economy: This is an economy in which the production and distribution of goods and services are centrally planned and controlled by the government. In a command economy, economic decisions are made by a central authority, such as a government or a communist party. 4. Mixed economy: This is an economy in which both the market and the government play a role in the production and distribution of goods and services. A mixed economy combines elements of a market economy, such as private ownership and competition, with elements of a command economy, such as government regulation and intervention Some key differences between a market economy and a command economy include: ● Private property: In a market economy, private individuals and firms own and control the means of production, while in a command economy, the means of production are owned and controlled by the state. ● Competition: In a market economy, firms compete with each other to sell goods and services, while in a command economy, competition is generally suppressed in favor of a planned allocation of resources. ● Prices: In a market economy, prices are determined by the interaction of supply and demand, while in a command economy, prices are set by the government. ● Economic incentives: In a market economy, economic incentives, such as the desire for profit, drive economic activity, while in a command economy, economic incentives may be less important because the government plays a more significant role in directing economic activity. 4 FACTORS OF PRODUCTION In economics, the four factors of production are the resources that are used to produce goods and services. They are: 1. Land: Land refers to the natural resources that are used in the production process, such as minerals, oil, and timber. 2. Labor: Labor refers to the work that is performed by people to produce goods and services. It includes both physical and mental effort. 3. Capital: Capital refers to the tools, machinery, and equipment that are used in the production process. It includes both physical capital, such as factories and machines, and financial capital, such as money invested in a business. 4. Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurship refers to the risk-taking and innovation that are required to create and operate a business. Entrepreneurs are the individuals who start and run businesses and who are willing to take on the risks and uncertainties associated with starting a new venture. These four factors of production are used in various combinations to produce different goods and services, and the relative importance of each factor varies depending on the type of production. PPC The Production Possibilities Curve (PPC) is a graphical representation of the trade-offs that an economy faces between producing different goods and services. It shows the maximum amount of one good or service that can be produced for every possible level of production of another good or service. The PPC is used to illustrate the concept of opportunity cost, which is the cost of a decision in terms of the next best alternative that must be given up. In economics, the opportunity cost of producing one good is the other good that must be given up in order to produce it. The PPC illustrates this concept by showing the trade-offs between producing different goods and services. The PPC is based on the assumption of constant technology and fixed resources, which means that it represents the maximum amount of one good that can be produced for every possible level of production of the other good, given the available resources and technology. As a result, the PPC illustrates the concept of opportunity cost, which is the cost of a decision in terms of the next best alternative that must be given up. The Law of Increasing Opportunity Cost states that as an economy increases the production of one good, the opportunity cost of producing that good will increase. This is because the resources that are used to produce the good are more specialized and could not be easily used to produce the other good. As a result, the opportunity cost of producing the good increases as more resources are devoted to its production. The PPC is typically drawn as a bowed-out shape, rather than a straight line, because it reflects the concept of opportunity cost, which is the cost of a decision in terms of the next best alternative that must be given up. Opportunity cost increases as more resources are devoted to the production of one good, because the resources that are used to produce the good are more specialized and could not be easily used to produce the other good. For example, consider an economy that produces two goods, wheat and timber. If the economy is producing only a small amount of wheat and a large amount of timber, the opportunity cost of producing additional wheat is relatively low because the resources used to produce wheat (such as land and labor) could easily be used to produce timber instead. As the economy increases the production of wheat, the opportunity cost of producing additional wheat increases because the resources used to produce wheat become more specialized and could not be easily used to produce timber. This relationship between opportunity cost and the production of goods is reflected in the bowed-out shape of the PPC. The PPC slopes downward from left to right because increasing the production of one good typically requires giving up some production of the other good, and the slope of the PPC becomes steeper as more resources are devoted to the production of one good. Here are some key points to consider when understanding the PPC: 1. The PPC is based on the assumption of constant technology and fixed resources: The PPC assumes that the economy has a fixed amount of resources and a constant level of technology. This means that the PPC represents the maximum amount of one good that can be produced for every possible level of production of the other good, given the available resources and technology. 2. The PPC is a graphical representation of trade-offs: The PPC shows the trade-offs that an economy faces between producing different goods and services. It slopes downward from left to right because increasing the production of one good typically requires giving up some production of the other good. 3. Points on the PPC represent different combinations of the two goods: The PPC is plotted on a graph with the quantity of one good on the horizontal axis and the quantity of the other good on the vertical axis. Points on the PPC represent different combinations of the two goods that can be produced, given the available resources and technology. 4. Points inside the PPC represent inefficient combinations: Points inside the PPC represent inefficient combinations of the two goods, because they can be produced using fewer resources. 5. Points on the PPC represent efficient or optimal combinations: Points on the PPC represent efficient combinations of the two goods, because they represent the maximum amount of one good that can be produced for every possible level of production of the other good. 6. Points outside the PPC are unattainable or unsustainable: Points outside the PPC are unattainable because they cannot be produced given the available resources and technology. There are several factors that can move the Production Possibilities Curve (PPC). Some of these factors include: 1. Economic growth: Economic growth refers to an increase in the productive capacity of an economy. Economic growth can be driven by increases in the quantity and quality of resources, such as labor, capital, and technology, as well as improvements in productivity and efficiency. 2. Technological progress: Technological progress refers to the development and adoption of new technologies that increase productivity and efficiency. Technological progress can move an economy by increasing the amount of goods and services that can be produced with a given amount of resources. 3. Changes in resource availability: Changes in the availability of resources, such as labor, capital, and raw materials. For example, if an economy has access to more resources, it may be able to produce more goods and services. The decrease in unemployment can move an economy from an inefficient point to a more efficient point on the Production Possibilities Curve (PPC). Unemployment occurs when people who are willing and able to work are unable to find employment. When unemployment is high, it means that there are fewer resources (labor) being used to produce goods and services, which can lead to an inefficient allocation of resources and an inefficient point on the PPC. On the other hand, when unemployment is low, it means that more resources (labor) are being used to produce goods and services, which can lead to a more efficient allocation of resources and a more efficient point on the PPC. In addition to decreasing unemployment, there are other factors that can move an economy from an inefficient point to a more efficient point on the PPC, such as economic growth, specialization and division of labor, technological progress, and changes in resource availability. Important Point to Note: Foreign trade can allow an economy to access goods and services that are not produced within its borders, which can allow people to consume outside the PPC. For example, if an economy imports goods and services that it does not produce domestically, it can consume a combination of goods and services that is not shown on the PPC. In addition, foreign trade can also allow an economy to specialize in the production of certain goods and services and trade them for other goods and services that it does not produce. This specialization and trade can lead to increased efficiency and allow an economy to consume outside the PPC. Points to remember: ● Every point on the PPC is optimal or efficient ● Every point inside the PPC is inefficient ● Every point outside the PPC is unattainable/unsustainable ● Curve is concave (bowed out) - LAW OF INCREASING OPPORTUNITY COST ● Curve is downward sloping straight line - CONSTANT OPPORTUNITY COST ● Consumption can happen outside the PPC due to Trade ABSOLUTE ADVANTAGE & ABSOLUTE ADVANTAGE Comparative advantage and absolute advantage are two concepts that are used to explain the relationship between production and trade. Comparative advantage refers to the ability of an individual, firm, or country to produce a good or service at a lower opportunity cost than another individual, firm, or country. In other words, an individual, firm, or country has a comparative advantage in the production of a good or service if it can produce it more efficiently than another individual, firm, or country. For example, consider two countries, A and B, that produce wheat and timber. If country A can produce 1 unit of wheat and 2 units of timber with the same resources that country B can use to produce 2 units of wheat and 1 unit of timber, country A has a comparative advantage in the production of wheat. This is because the opportunity cost of producing wheat in country A (1 unit of timber) is lower than the opportunity cost of producing wheat in country B (2 units of timber). Absolute advantage refers to the ability of an individual, firm, or country to produce a good or service more efficiently than another individual, firm, or country. In other words, an individual, firm, or country has an absolute advantage in the production of a good or service if it can produce it using fewer resources than another individual, firm, or country. For example, consider two countries, A and B, that produce wheat and timber. If country A can produce 2 units of wheat with the same resources that country B can use to produce 1 unit of wheat, country A has an absolute advantage in the production of wheat. This is because country A can produce the same amount of wheat using fewer resources than country B. It is important to note that comparative advantage and absolute advantage are not the same thing. A country or individual can have a comparative advantage in the production of a good or service without having an absolute advantage in its production. Similarly, a country or individual can have an absolute advantage in the production of a good or service without having a comparative advantage in its production. DEMAND & SUPPLY Demand, supply, and market equilibrium are fundamental concepts in economics that describe the relationship between the quantity of a good or service that buyers are willing and able to purchase (demand) and the quantity of the good or service that sellers are willing and able to provide (supply). Demand refers to the quantity of a good or service that buyers are willing and able to purchase at a given price. It is typically represented by a demand curve, which shows the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity demanded. The demand curve slopes downward from left to right, indicating that as the price of a good or service decreases, the quantity demanded increases. There are several reasons why the demand curve slopes downward: 1. The law of diminishing marginal utility: The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as the quantity of a good or service consumed increases, the marginal utility (additional satisfaction or benefit) derived from consuming each additional unit of the good or service will decrease. As a result, people are willing to pay a higher price for the first unit of a good or service than for subsequent units, which leads to a downwardsloping demand curve. 2. Income Effect: The demand for a good or service may also be influenced by an individual's income. As income increases, people may be able to afford to purchase more of a good or service, which leads to an increase in the quantity demanded at each price. 3. Prices of related goods: The demand for a good or service may also be influenced by the prices of related goods. For example, if the price of a substitute good (a good that can be used in place of another good) increases, the demand for the original good may increase, because people may switch to the original good as an alternative. 4. Tastes and preferences: The demand for a good or service may also be influenced by an individual's tastes and preferences. If people prefer a good or service more, they may be willing to pay a higher price for it, which leads to an increase in the quantity demanded at each price. Supply refers to the quantity of a good or service that sellers are willing and able to provide at a given price. It is typically represented by a supply curve, which shows the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity supplied. The supply curve slopes upward from left to right, indicating that as the price of a good or service increases, the quantity supplied increases. Market equilibrium occurs when the quantity of a good or service that buyers are willing and able to purchase at a given price (demand) is equal to the quantity of the good or service that sellers are willing and able to provide at that price (supply). At market equilibrium, there is no excess supply or excess demand, and the price of the good or service is stable. If the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied at a given price, there is excess demand for the good or service, and the price will tend to increase. On the other hand, if the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at a given price, there is excess supply of the good or service, and the price will tend to decrease. ELASTICITY Elasticity is a measure of how responsive the quantity demanded or supplied of a good or service is to a change in a specific variable, such as price. Elasticity is an important concept in economics because it helps to understand how changes in variables such as price can affect the quantity of a good or service that is demanded or supplied. There are several different types of elasticity, including price elasticity of demand, price elasticity of supply, cross-price elasticity of demand, and income elasticity of demand. Price elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good or service to a change in its price. It is calculated as the percentage change in the quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price. If the quantity demanded of a good or service is relatively responsive to a change in its price, it is said to be elastic. If the quantity demanded is relatively unresponsive to a change in price, it is said to be inelastic. Price elasticity of demand = (% change in quantity demanded) / (% change in price) Here are a few examples of goods and services with different levels of price elasticity of demand: 1. Inelastic demand: ● Prescription drugs: The demand for prescription drugs is typically inelastic because they are often necessary for maintaining health and there are few substitutes available. ● Gasoline: The demand for gasoline is typically inelastic because it is necessary for transportation and there are few substitutes available. 2. Elastic demand: ● Luxury goods: The demand for luxury goods such as designer clothing and highend electronics is typically elastic because there are many substitutes available and the good is not considered a necessity. ● Recreational activities: The demand for recreational activities such as movie tickets or concert tickets is typically elastic because there are many substitutes available and the activity is not considered a necessity. 3. Unit elastic demand: ● Fast food: The demand for fast food is typically unit elastic because there are many substitutes available, but the good is considered convenient and may not be easily replaced. ● Air travel: The demand for air travel is typically unit elastic because there are some substitutes available, but the goods are considered convenient and may not be easily replaced. Price elasticity of supply measures the responsiveness of the quantity supplied of a good or service to a change in its price. It is calculated in a similar manner to price elasticity of demand. If the quantity supplied of a good or service is relatively responsive to a change in its price, it is said to be elastic. If the quantity supplied is relatively unresponsive to a change in price, it is said to be inelastic. Price elasticity of supply = (% change in quantity supplied) / (% change in price) Here are a few examples of goods and services with different levels of price elasticity of supply: 1. Inelastic supply: ● Agricultural products: The supply of agricultural products is typically inelastic because it takes time to increase production, and it is difficult to quickly ramp up or down production due to the time and resources required to grow crops or raise livestock. ● Real estate: The supply of real estate is typically inelastic because it takes time to build new properties or make changes to existing ones, and it is difficult to quickly increase or decrease the supply of real estate. 2. Elastic supply: ● Manufactured goods: The supply of manufactured goods is typically elastic because it is relatively easy to increase or decrease production in response to changes in demand or price. ● Services: The supply of services is typically elastic because it is relatively easy to increase or decrease the supply of services in response to changes in demand or price. 3. Unit elastic supply: ● Natural resources: The supply of natural resources such as oil or minerals is typically unit elastic because it takes time to increase or decrease production, but the supply can be adjusted to some extent in response to changes in demand or price. ● Labor: The supply of labor is typically unit elastic because it takes time for people to enter or exit the labor market, but the supply can be adjusted to some extent in response to changes in demand or price. Cross-price elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of the demand for one good or service to a change in the price of another good or service. It is calculated as the percentage change in the demand for one good or service divided by the percentage change in the price of another good or service. Cross-price elasticity of demand = (% change in demand for good A) / (% change in price of good B) Income elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of the demand for a good or service to a change in an individual's income. It is calculated as the percentage change in the demand for a good or service divided by the percentage change in income. Income elasticity of demand = (% change in demand for a good or service) / (% change in income) Normal goods are goods for which demand increases as income increases. In general, the income elasticity of demand for normal goods is positive, meaning that the demand for the goods increases as income increases. The income elasticity of demand for normal goods is typically greater than zero, but it can vary depending on the specific good or service. Inferior goods are goods for which demand decreases as income increases. In general, the income elasticity of demand for inferior goods is negative, meaning that the demand for the good decreases as income increases. The income elasticity of demand for inferior goods is typically less than zero, but it can vary depending on the specific good or service. TOTAL REVENUE TEST & PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND The total revenue test is a method for determining the price elasticity of demand for a good or service. It involves calculating the total revenue (the price of a good or service multiplied by the quantity sold) before and after a change in price and comparing the results. If the total revenue increases after a price increase, it indicates that the demand for the good or service is elastic, meaning that the quantity demanded is relatively responsive to changes in price. This is because an increase in price leads to an increase in total revenue when the quantity demanded is elastic. If the total revenue decreases after a price increase, it indicates that the demand for the good or service is inelastic, meaning that the quantity demanded is relatively unresponsive to changes in price. This is because an increase in price leads to a decrease in total revenue when the quantity demanded is inelastic. If the total revenue remains unchanged after a price increase, it indicates that the demand for the good or service is unit elastic, meaning that the quantity demanded is neither very responsive nor very unresponsive to changes in price. The total revenue test is a useful tool for businesses to understand how changes in price may affect their revenue and to make pricing decisions accordingly. SURPLUS Consumer surplus and producer surplus are measures of the economic welfare or well-being of consumers and producers, respectively. They are used to analyze the benefits and costs of market transactions and to understand the distribution of resources within an economy. Consumer surplus is the difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay for a good or service and the actual price they pay. It represents the amount of value or utility that a consumer derives from a good or service beyond what they paid for it. For example, if a consumer is willing to pay $10 for a good and they are able to purchase it for $5, their consumer surplus is $5. Producer surplus is the difference between the minimum price a producer is willing to accept for a good or service and the actual price they receive. It represents the amount of profit or excess revenue that a producer earns from selling a good or service. For example, if a producer is willing to sell a good for $5 and they are able to sell it for $10, their producer surplus is $5. Consumer surplus and producer surplus can be represented graphically by the area under the demand curve and above the price for consumers and the area above the supply curve and below the price for producers. A price floor is a government-imposed minimum price for a good or service. It is used to protect the interests of producers by ensuring that they receive a minimum price for their goods or services. A price ceiling is a government-imposed maximum price for a good or service. It is used to protect the interests of consumers by ensuring that they do not have to pay excessively high prices for goods or services. A price floor is said to be binding if it is set above the equilibrium price, and it is said to be nonbinding if it is set below the equilibrium price. A price ceiling is said to be binding if it is set below the equilibrium price, and it is said to be non-binding if it is set above the equilibrium price. If a price floor or price ceiling is binding, it can cause market disequilibrium and lead to a surplus or shortage of the good or service in question. For example, if a price floor is set above the equilibrium price, it can lead to a surplus of the good or service because producers are able to sell their goods or services at a higher price, but consumers may be unwilling to pay the higher price, leading to excess supply. Conversely, if a price ceiling is set below the equilibrium price, it can lead to a shortage of the good or service because consumers are willing to pay a higher price, but producers are unable to sell their goods or services at the higher price, leading to excess demand. Deadweight loss is a measure of the efficiency of a market. It represents the loss of economic welfare or well-being that occurs when a market is not in equilibrium, or when the price and quantity of a good or service do not reflect the full cost and benefits of production and consumption. There are several scenarios in which deadweight loss can be created: 1. Price controls: Price floors and price ceilings can create deadweight loss if they are set above or below the equilibrium price, respectively. This is because they can cause a surplus or shortage of the good or service in question, leading to a loss of economic welfare. 2. Taxes and subsidies: Taxes and subsidies can create deadweight loss if they are not implemented in a way that reflects the full cost and benefits of a good or service. For example, if a tax is imposed on a good or service, it can increase the price and reduce the quantity demanded, leading to a loss of economic welfare. Conversely, if a subsidy is provided for a good or service, it can reduce the price and increase the quantity demanded, leading to a loss of economic welfare if the subsidy is not justified by the full cost and benefits of the good or service. 3. Externalities: Externalities are the costs or benefits of a good or service that are not reflected in the market price. They can create deadweight loss if they are not internalized, or if the cost or benefit is not fully accounted for in the price of the good or service. For example, if a good or service generates negative externalities such as pollution, it can create a loss of economic welfare if the cost of the pollution is not reflected in the price of the good or service. 4. Market power: Market power is the ability of a firm to influence the price of a good or service. It can create deadweight loss if a firm is able to set a price that is above the equilibrium price, leading to a reduction in the quantity demanded and a loss of economic welfare. Trade and tariffs can create deadweight loss in a number of ways. Tariffs, which are taxes placed on imported goods, can reduce the quantity of goods traded and increase the price of those goods, leading to a reduction in consumer surplus and producer surplus. This reduction in surplus is the deadweight loss. For example, consider a market for a good that is produced domestically and imported from a foreign country. Without a tariff, the market price of the goods would be determined by the intersection of the domestic supply curve and the demand curve, as shown in the diagram below. This results in a certain level of consumer surplus (the area above the market price and below the demand curve) and producer surplus (the area above the supply curve and below the market price). [Diagram showing supply and demand curves for a good without a tariff] If a tariff is imposed on the imported goods, the price of the goods will increase. This shift in the supply curve will lead to a reduction in the quantity of the goods that is traded, as shown in the diagram below. The consumer surplus is reduced by the area of the triangle between the new demand curve and the old demand curve, and the producer surplus is increased by the area of the triangle between the new supply curve and the old supply curve. The area of the rectangle between the new demand curve and the new supply curve represents the deadweight loss caused by the tariff. [Diagram showing supply and demand curves for a good with a tariff] Tariffs can also lead to deadweight loss by causing inefficiencies in production. If a tariff is imposed on an imported intermediate good that is used in the production of a domestic good, it may become more expensive for domestic producers to produce the good. This could lead to domestic producers becoming less competitive in the market and potentially reducing their output, leading to a deadweight loss. Trade restrictions, such as quotas or import bans, can also create deadweight loss by limiting the quantity of goods that can be traded and distorting the market price. This can lead to a reduction in consumer surplus and producer surplus, similar to the effects of tariffs. COSTS OF PRODUCTION In economics, cost refers to the expenses a firm incurs in order to produce a good or service. These costs can be categorized into two main types: fixed costs and variable costs. Fixed costs (FC) are expenses that do not vary with the quantity of output produced. These costs are "fixed" in the short run, meaning that they cannot be changed in the short term. Examples of fixed costs include rent, property taxes, and salaries of executives. Average fixed cost (AFC) is the fixed cost per unit of output. It is calculated by dividing the total fixed cost by the quantity of output. Variable costs (VC), on the other hand, do vary with the quantity of output produced. These costs increase as the firm produces more and decrease as the firm produces less. Examples of variable costs include wages of production workers, raw materials, and electricity used in the production process. Average variable cost (AVC) is the variable cost per unit of output. It is calculated by dividing the total variable cost by the quantity of output. Total cost (TC) is the sum of a firm's fixed costs and variable costs. It represents the total expense incurred by the firm in the production process. Average total cost (ATC) is the total cost per unit of output. It is calculated by dividing the total cost by the quantity of output. The average total cost curve is the sum of the average fixed cost curve and the average variable cost curve. As the quantity of output increases, the average fixed cost decreases, while the average variable cost increases. At low levels of output, the average fixed cost makes up a larger portion of the average total cost, while at high levels of output, the average variable cost makes up a larger portion. Marginal cost (MC) is the cost of producing one additional unit of output. It is calculated by taking the change in total cost that results from a change in the quantity of output. In other words, it is the additional cost incurred by producing one more unit of output. The marginal cost curve intersects the average total cost curve at its minimum point, which occurs at the minimum efficient scale of production. At output levels below the minimum efficient scale, the marginal cost is below the average total cost, leading to a decrease in average total cost. At output levels above the minimum efficient scale, the marginal cost is above the average total cost, leading to an increase in average total cost. The relationship between ATC, AFC, AVC, and MC can be illustrated with a graph. In the graph, the horizontal axis represents the quantity of output, and the vertical axis represents the cost. The ATC curve is U-shaped, with the minimum point at the minimum efficient scale of production. The AFC curve is downward-sloping and eventually becomes horizontal as the quantity of output increases. The AVC curve is also downward-sloping and eventually becomes horizontal as the quantity of output increases. The MC curve intersects the AVC curve at its minimum point and is upward-sloping. The law of diminishing marginal returns states that, as the quantity of a variable input is increased while the quantities of all other inputs are held constant, the marginal product of the variable input will eventually decline. This occurs because the additional inputs are being applied to a fixed amount of capital and labor, which means that the additional inputs are being used less and less efficiently. The relationship between the law of diminishing marginal returns and marginal cost (MC) can be illustrated with a graph. In the graph, the horizontal axis represents the quantity of output, and the vertical axis represents the cost. As the quantity of output increases, the marginal cost initially decreases, due to the law of diminishing marginal returns. At some point, however, the marginal cost begins to increase, as the additional inputs being used to produce the additional output become less and less efficient. The point at which the marginal cost begins to increase is known as the point of diminishing returns. [Graph showing the relationship between the law of diminishing marginal returns and marginal cost] Marginal revenue is the change in total revenue that results from a change in the quantity of output sold. It is calculated by taking the change in total revenue and dividing it by the change in the quantity of output. There is a relationship between marginal revenue and elasticity, particularly in the context of price elasticity of demand. When the price elasticity of demand is elastic (greater than 1), a small percentage change in price leads to a larger percentage change in the quantity demanded. This means that a small increase in price will lead to a large decrease in the quantity demanded, resulting in a decrease in total revenue. In this case, the marginal revenue will be negative. On the other hand, when the price elasticity of demand is inelastic (less than 1), a small percentage change in price leads to a smaller percentage change in the quantity demanded. This means that a small increase in price will lead to a smaller decrease in the quantity demanded, resulting in an increase in total revenue. In this case, the marginal revenue will be positive. [Graph showing the relationship between marginal revenue and elasticity] MARKET STRUCTURES: There are several types of markets in economics, including: 1. Perfect competition: This is a market structure in which there are many buyers and sellers, all offering similar products. The firms in a perfectly competitive market are price takers, meaning they have no control over the price of the product and must accept the market price. 2. Monopoly: This is a market structure in which there is only one seller of a particular product. The firm in a monopoly has complete control over the price of the product and can charge a higher price than firms in a competitive market. 3. Oligopoly: This is a market structure in which there are a small number of firms that dominate the market. The firms in an oligopoly have some control over the price of the product, but they must also consider the actions of their competitors when setting prices. 4. Monopolistic competition: This is a market structure in which there are many firms that offer similar, but not identical, products. The firms in a monopolistically competitive market have some control over the price of the product, but they also face competition from other firms. 5. Pure competition: This is a market structure in which there are many buyers and sellers, all offering identical products. The firms in a pure competitive market are price takers, meaning they have no control over the price of the product and must accept the market price