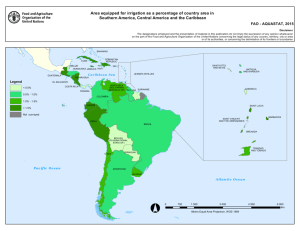

são roque Antiques & Art Gallery Saint Michael Slaying the Devil — Spanish Colonial, Peru (?), 17th century Saint Michael Slaying the Devil Polychrome mahogany Spanish Colonial, Peru (?), 17th century Dim: 102.0 × 50.0 cm F1332 Important 17th century depiction of Saint Michael Slaying the Devil, possibly produced in Peru. Wood carved and of exuberant polychrome decoration, the sculpture used a local raw material that was abundant in its geographical production area, most certainly Honduran mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), a precious timber native to Central and South America. It is possible that the timber’s origin was Tahuamanu tropical forest, the oldest in Peru, which corresponds to a section of the Amazonian rain forest. Towards the end of the 16th century, Pope Gregory XIII (1502 – 1585) determined that only the Archangels referred in the Holy Scriptures — Gabriel, Raphael, and Michael — were worthy of being portrayed, and that, beyond these, all other representations of angels and archangels would be heretical. In Spanish controlled central and south American territories however, the production of spurious Saints iconography, such as Uriel’s, Salatiel’s or Barachiel’s, continued to be encouraged, particularly by the Society of Jesus, a highly influential religious congregation in those overseas regions1. Seen as protective entities in the fight between Good and Evil, the cult of angels and archangels reached, and still maintains today, widespread popularity in Spanish America, wherefore the Pope’s prohibition did not have significant impact on local religious practices, particularly amongst indigenous populations. From amidst the three officially approved Archangels, Michael was particularly favoured as the military angel, the Commander of the Armies of God and, as such, Defender of the True Faith, who banned the rebel angels, headed by Lucifer, from Heaven2. In this sculptural composition the Archangel is attired in Classical Roman uniform, as evidenced by the sandals and suit of armour, his red cape featuring evidence of Mannerist inspired gilt foliage decorative motifs that are repeated on the stand supporting the figure. On his head he sports a morion, the military casket originating from the Kingdom of Castille that was commonly used by the Spanish Conquistadores in the 16th and 17th centuries exploration of the American Continent. For their shape, as well as for their polychrome decoration of yellow, red, and blue pigments, Saint Michael’s wings, although of later production, can be associated to a native South American bird, the scarlet macaw (Ara macao). As suggested by its posture, the Archangel should be wielding a sword in the right hand, while in the left he would probably be holding a chain that secured the devil, or a scales for weighing the souls, one of his recurrent attributes. Most certainly inspired by the numerous printed engravings of Catholic Saints circulated by missionaries and merchants, such as those by Hieronymus Wierix (1553 – 1619)3, locally produced See: Marjorie TRUSTED, The Arts of Spain Iberia and Latin America 1450 – 1700, V&A publications, 2007, p.180. See: Marjorie TRUSTED, The Arts of Spain Iberia and Latin America 1450 – 1700, p. 183. 3 Flemish engraver famous for his imitations of Albrecht Dürer’s prints, which were widely circulated in both Spanish and Portuguese America. 1 2 SÃO ROQUE ∫ ANTIQUES & ART GALLERY sculptural and pictorial images of this Archangel exhibit consistent similarities, independently of the artisans that might have produced them. As such, our Saint Michael is endowed with a particularly original, and certainly rare detail, as the devil being slain by the Archangel features close analogies to Supay4 the Inca God of death and leader of malignant spirits. This being said, this sculptural depiction of the Archangel Saint Michael is an unequivocal symbol of the indoctrination pursued by the Society of Jesus, and by other Religious Orders operating in these American territories. Their main purpose being the conversion of the indigenous populations, these institutions attempted at communicating through imagery and metaphors that could be easily understood and absorbed by the newly evangelized populations. As such, our Saint Michael illustrates rather eloquently a metaphor alluding to the victory of Christianity over Paganism, and the former apparent superiority. s BMS 4 In Inca, Quechua and Aymara mythology, Supay, a truly Andean Hades, is associated with death and identified as the ruler of Ukhu Pacha, whose location would be in modern day Bolivia. His main purpose would be to harm the human race. To this day, local Andean communities still use the term Supay to refer to the devil. SÃO ROQUE ∫ ANTIQUES & ART GALLERY Rua de São Bento, 199B ∫ 1250 – 219 Lisbon ∫ T +351 213 960 734 geral@saoroquearte.pt ∫ antiguidadessaoroque.com