Uploaded by

Thomas Butters

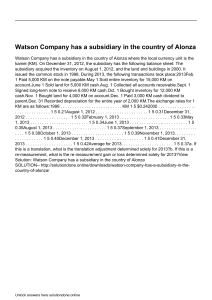

Knowledge Flows, Subsidiary Power, and Rent-Seeking in MNCs

advertisement